Abstract

BACKGROUND

When evaluating deep brain stimulation (DBS) for newer indications, patients may benefit from trial stimulation prior to permanent implantation or for investigatory purposes. Although several case series have evaluated infectious complications among DBS patients who underwent trials with external hardware, outcomes have been inconsistent.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether a period of lead externalization is associated with an increased risk of infection.

METHODS

We conducted a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses compliant systematic review of all studies that included rates of infection for patients who were externalized prior to DBS implantation. A meta-analysis of proportions was performed to estimate the pooled proportion of infection across studies, and a meta-analysis of relative risks was conducted on those studies that included a control group of nonexternalized patients. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed via I2 index.

RESULTS

Our search retrieved 23 articles, comprising 1354 patients who underwent lead externalization. The pooled proportion of infection was 6.9% (95% CI: 4.7%-9.5%), with a moderate to high level of heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 62.2%; 95% CI: 40.7-75.9; P < .0001). A total of 3 studies, comprising 212 externalized patients, included a control group. Rate of infection in externalized patients was 5.2% as compared to 6.0% in nonexternalized patients. However, meta-analysis was inadequately powered to determine whether there was indeed no difference in infection rate between the groups.

CONCLUSION

The rate of infection in patients with electrode externalization is comparable to that reported in the literature for DBS implantation without a trial period. Future studies are needed before this information can be confidently used in the clinical setting.

Keywords: Adverse events, Complications, Deep brain stimulation, Externalization, Infection

ABBREVIATIONS

- DBS

deep brain stimulation

- EVDs

external ventricular drains

- ICP

intracranial pressure

- IPG

internal pulse generator

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an established therapeutic modality in the treatment of Parkinson disease (PD), essential tremor, and dystonia and is currently under investigation for numerous other conditions.1 Despite its promise, the surgical implantation of DBS hardware is not without risk.2 Hardware-related infection is among the most recognized complications after DBS, often leading to additional operations, removal of implanted hardware, extended hospitalization, and prolonged use of antibiotics.3

The incidence of DBS-related infection ranges from 1.5% to 22.2%.4-21 This disparity may relate to several factors, including varying indications for DBS, antibiotic prophylaxis, follow-up time, study design, and other risk factors. It is unclear how much hardware (or lead) externalization contributes or exacerbates the risk of infection. Historically, electrode externalization has been utilized in a period between intracerebral lead implantation and internal pulse generator (IPG) placement, during which the electrodes are temporarily connected to extension leads for trial stimulation prior to permanent hardware internalization. Such a trial period may be particularly useful for conditions such as chronic pain syndromes, in which intraoperative testing for DBS efficacy may be difficult and unreliable. Furthermore, a period of trial stimulation allows for the acquisition of neurophysiological data, critical to guiding us in future research and development in the area of DBS.22 The process of electrode externalization may enable opportunities to develop future therapeutic applications, including enhancing clinical efficacy and limiting the adverse effects of DBS therapy.

Although the potential benefits from lead externalization are appreciated, data regarding its safety are both limited and controversial. The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate whether lead externalization is associated with an increased risk of infection after DBS implantation. We believe the results of this study will allow medical providers to better understand the risks of this method, give patients the necessary information to make a more informed decision about their care and enable rationale trial design for scientific investigation.

METHODS

Search Strategy

This systemic review was performed in accordance with the criteria outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 guidelines.23 No patient information was used in this article, so Institutional Review Board approval and patient consent were not required. A computerized search was conducted up to February 2020 on the PubMed and Web of Science online databases. The search strategy was based on the population, intervention, comparison, outcome framework and was developed using the following main subject terms: deep brain stimulation, infection, erosion, and skin (Text, Supplemental Digital Content A). A sample search strategy can be found in Table 1. The reference lists of the included studies were searched to obtain additional articles.

TABLE 1.

Sample Search Strategy for PubMed

| Number | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | Deep brain stimulation [mesh] |

| 2 | Infection |

| 3 | Erosion |

| 4 | Skin |

| 5 | 2 or 3 or 4 |

| 6 | 1 and 5 |

| 7 | Filters: Humans; English |

Study Selection

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) human subjects, (2) English language, (3) included patients greater than 19 yr of age, (4) peer-reviewed original research with full-text available (single-subject case reports, reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded), (5) included patients who were externalized prior to full DBS implantation, and (6) reported rates of infection with respect to those patients who were externalized. Studies were excluded if they did not meet all the inclusion criteria. Skin erosions were distinguished from infections and were not included in the infection count.

In the first phase, all studies were evaluated for eligibility based on the title and abstract. In the second phase, full-text articles were evaluated on meeting the inclusion criteria. Study selection and data extraction were independently performed in a standardized form by the first author, supervised by 2 independent reviewers.

Quality Assessment

Tools for assessing the quality of studies evaluating surgery and hardware-related complications, such as infection, are generally not available.24 For this reason, the authors were unable to compare the methods of included studies using an established quality assessment standard. Nevertheless, factors related to internal validity were extracted for further assessment. Based on the analysis of levels of evidence,25 1 study was classified as level I,26 2 studies were classified as level III,27,28 and the remaining 20 studies were classified as level IV.11,22,29-46

Data Extraction

Relevant information from each included article was extracted and presented in 2 tables containing the following items: (1) author and date of publication, (2) number of patients who underwent electrode externalization and were followed-up, (3) follow-up duration, (4) use of antibiotic prophylaxis, (5) indication for external trial stimulation, (6) duration of external trial stimulation, (7) study design, (8) the presence of a control group, (9) whether or not infection was defined (Table 2), (10) number of patients with infection, (11) infection rate, (12) DBS indication for those patients with infection, (13) time from DBS surgery to infection, (14) microbiology of infection, (15) site of infection, (16) management of infection, and (17) whether or not there was an increased risk of infection with externalization (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Study Characteristics of Studies Relating to Electrode Externalization and Infection

| Author, year | No. externalized | Mean follow-up in months (range) | Antibiotic prophylaxis? | Indication (no. of patients) | Duration of externalization (days) | Study design | Nonexternalized control group? | Defined infection? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franco, 201834 | 4 | 6.0 (6.0) | INS | PWS (4) | 5 | P | No | No |

| Boccard, 201739 | 24 | 38.9 (24-65) | INS | Pain (24) | 7 | R | No | No |

| Rosa, 201722 | 105 | 12.0 (INS) | Yes | PD (105) | 2-7 | R | No | Yes |

| Lee, 201427 | 109 | 58.9 (24-84) | INS | PD (45); dystonia (48); tremor (12); pain (3); epilepsy (1) | 2-6 | R | No | No |

| Pepper, 201333 | 100 | INS | Yes | INS | 3-7 | R | Yes | Yes |

| Schlaepfer, 201335 | 7 | INS (3-8) | INS | MDD (7) | 2 | P | No | No |

| Ackermans, 201126 | 6 | 12.0 (12) | INS | TS (6) | ≤7 | P | No | No |

| Vergani, 201040 | 141 | 55.2 (9-120) | Yes | PD (141) | 2-3 | R | No | No |

| Mehrkens, 200941 | 12 | 60.0 (37-90) | Yes | Dystonia (12) | 3-5 | R | No | No |

| Owen, 200742 | 32 | 3.0 (INS) | INS | Pain (32) | 7 | P | No | No |

| Hamani, 200643 | 21 | INS (108 max) | INS | Pain (21) | 5 | R | No | No |

| Constantoyannis, 200538 | 26 | 24.0 (6-60) | Yes | INS | 3-5 | P | Yes | No |

| Green, 200544 | 7 | 20.6 (12-36) | INS | Pain (7) | Few days | P | No | No |

| Bojanic, 200428 | 86 | INS | Yes | PD (42); dystonia (16); pain (16); tremor (6); MS (6) | 7 | R | Yes | No |

| Temel, 200411 | 106 | 42.6 (INS) | Yes | PD (90); tremor (10); pain (3); TS (2); HD (1) | 7 | R | No | No |

| Oh, 200245 | 79 | 33.0 (8-84) | Yes | PD (53); tremor (9); pain (9); epilepsy (3); dystonia (3); HD (1); MS (1) | 7 | R | No | No |

| Vesper, 200246 | 38 | 12.0 (INS) | INS | PD (38) | 4 | R | No | No |

| Vercueil, 200136 | 19 | 45.9 (6-132) | INS | Dystonia (19) | INS | R | No | No |

| Kumar, 199729 | 68 | 78.0 (6-180) | INS | Pain (68) | 5-7 | P | No | No |

| Benabid, 199637 | 117 | INS (6-90) | Yes | PD (80); tremor (27); dystonia (6); MS (4) | 7 | R | No | No |

| Levy, 198730 | 141 | 81.6 (24-168) | INS | Pain (141) | 1 to several days | R | No | No |

| Dieckmann, 198231 | 46 | INS (6-54) | INS | Pain (46) | INS | P | No | No |

| Plotkin, 198232 | 60 | INS (6-42) | Yes | Pain (60) | At least 7 d | P | No | No |

HD, Huntington disease; INS, information not supplied; MDD, major depressive disorder; MS, multiple sclerosis; No., number; P, prospective; PD, Parkinson disease; PWS, Prader-Willi syndrome; R, retrospective; TS, Tourette syndrome.

TABLE 3.

Outcomes of Studies Relating to Electrode Externalization and Infection

| Author, year | No. of patients with infection | Infection rate | Indication (no. of patients) | Average time to infection (months) | Microbiology of infection (no. of infections) | Site of infection (no. of infections) | Management (no. of infections) | Increased risk? (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franco, 201834 | 2 | 50.0 | PWS (2) | 4 | INS | C (1), IPG (1) | A (1), RH (1) | NA |

| Boccard, 201739 | 5 | 20.8 | Pain (5) | INS | INS | INS | RH (6) | NA |

| Rosa, 201722 | 3 | 2.9 | PD (3) | 6 | Staphylococcus aureus (2), Nocardia farcinica (1) | IPG (3) | A, RH (3) | No (.054)a |

| Lee, 201427 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pepper, 201333 | 4 | 4.0 | PD (3) tremor (1) | 2.1 | Gram negative rod (1), Klebsiella pneumoniae (1), coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Enterobacter intermedius, and Candida famata (1) | IPG (1), IPG and BH (1), BH (2) | RH (4) | No (.78) |

| Schlaepfer, 201335 | 2 | 28.6 | MDD (1) | INS | INS | IPG (2) | INS | INS |

| Ackermans, 201126 | 1 | 16.7 | TS (1) | INS | S. aureus (1) | IPG (1) | A (1) | NA |

| Vergani, 201040 | 8 | 5.7 | PD (8) | INS | S. aureus (2), Pseudomonas (2), S. epidermidis (2) | Intracranial lead (2), IPG (6) | RH (3); A (3); A, RH (2) | NA |

| Mehrkens, 200941 | 1 | 8.3 | Dystonia (1) | 0.5 | INS | BH (1) | RH (1) | NA |

| Owen, 200742 | 2 | 6.3 | Pain (2) | INS | INS | INS | A (2) | NA |

| Hamani, 200643 | 1 | 4.8 | Pain (1) | INS | INS | INS | RH (2) | NA |

| Constantoyannis, 200538 | 4 | 15.3 | INS | INS | INS | INS | A/RH (INS) | Yes (.003) |

| Green, 200544 | 1 | 14.3 | Pain (1) | INS | INS | INS | A, RH (1) | NA |

| Bojanic, 200428 | 3 | 3.5 | Pain (3) | INS | N/A | IPG (3) | INS | No (<.099) |

| Temel, 200411 | 4 | 3.8 | PD (4) | 1.9 | S. aureus (4) | IPG (2), IPG and C (1), C (1) | A (2); A, D, RH (2) | NA |

| Oh, 200245 | 10 | 12.7 | Dystonia (2); pain (2); PD (5); tremor (1) | 10.2 | S. aureus (2), Mycobacterium fortuitum (1), Enterobacter (1), Pseudomonas (1) | BH (3), BH and C (1), IPG (1), C (5) | A, D (1); A, D, RH (5); RH (4) | NA |

| Vesper, 200246 | 2 | 5.3 | PD (2) | INS | INS | IPG (2) | RH (2) | NA |

| Vercueil, 200136 | 1 | 5.3 | Dystonia (1) | INS | INS | BH (1) | RH (1) | NA |

| Kumar, 199729 | 4 | 5.9 | Pain (4) | INS | INS | INS | A (3); RH (1) | NA |

| Benabid, 199637 | 3 | 2.6 | INS | INS | INS | C (3) | RH (3) | NA |

| Levy, 198730 | 17 | 12.1 | Pain (17) | INS | S. epidermidis (9), S. aureus (6), Propionibacterium acnes (2), Group B Streptococcus (1), Micrococcus (1), Enterobacter cloacae (1) | BH (19), IPG (3), C (1) | A (4); A, D (8); A, RH (11) | NA |

| Dieckmann, 198231 | 2 | 4.3 | Pain (2) | INS | INS | INS | INS | NA |

| Plotkin, 198232 | 2 | 3.3 | Pain (2) | 7.5 | INS | C (1) Scalp, not specified (1) | A (1); A, RH (1) | NA |

A, antibiotics; BH, on scalp overlying burr hole; C, on scalp overlying connecting cable; D, debridement; INS, information not supplied; IPG, internal pulse generator; MDD, major depressive disorder; NA, not applicable; No., number; PD, Parkinson's disease; PWS, Prader-Willi syndrome; RH, removal of hardware; TS, Tourette syndrome.

Although this study did not include a control group, they performed a comparison of the incidence of infection in their cohort with rates of infection previously reported in the literature.

Statistical Analysis

A meta-analysis of proportions was performed using MedCalc (MedCalc Software Ltd) version 19.0.5 in order to estimate the pooled proportion of infection across studies. MedCalc uses a Freeman-Tukey transformation47 to calculate the weighted summary proportion under the fixed- and random-effects model.48 Additionally, we used MedCalc to perform a meta-analysis of relative risk on the subgroup of studies that included a control group of nonexternalized patients. For this analysis, MedCalc uses the Mantel-Haenszel49 method for calculating the weighted pooled relative risk under the fixed-effects model and then incorporates the heterogeneity statistic to calculate the summary relative risk under the random-effects model.48 In order to assess the possible effects of study design (retrospective vs prospective) and duration of externalization (<7 d vs ≥7 d) on the rate of infection, we performed a meta-regression with the “metareg” command using Stata (StataCorp LLC) version 15.1. All other outcomes were assessed by descriptive statistical measures. A P value of <.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Because of potential heterogeneity across studies, we determined that a more conservative estimate of proportions was best representative of our study group, and therefore, the random-effects model was justified as the preferred model for our analyses.50 Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 value. In accordance with the recommendation by Higgins et al,51 I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% may correspond with low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively.

RESULTS

Study Selection

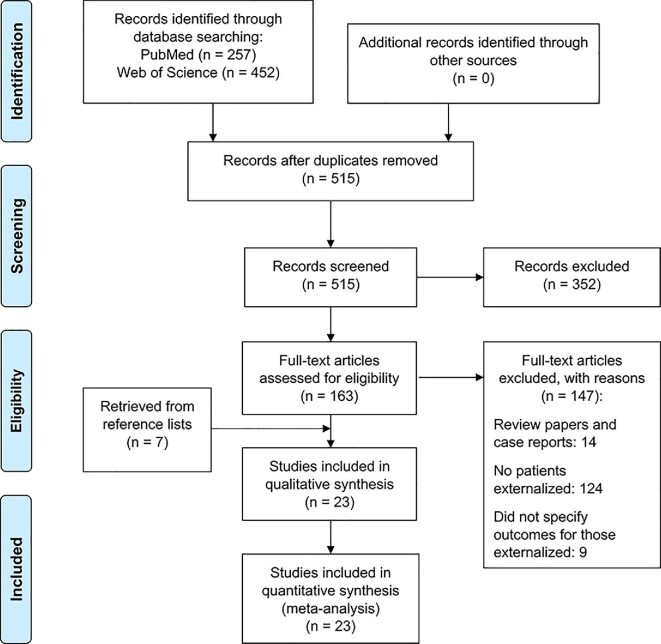

The literature search yielded a total of 515 articles after duplicates were removed. After the first phase of screening, 352 articles were excluded, leaving 163 articles that underwent full-text review. After the second phase of screening, an additional 78 articles were excluded, yielding a total of 16 articles from our search strategy. An additional 7 articles were included from a search of reference lists, resulting in a total of 23 articles that were included in our study.11,22,26-46 The process of study selection is represented in a PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1.23 A list of the articles that were excluded after full-text review, with reasons for exclusion, can be found in Text, Supplemental Digital Content B.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing systematic study selection.

Study Characteristics

The study characteristics of the selected articles are presented in Table 2, comprising 23 studies between 1982 and 2018, with a total of 1354 patients (mean: 58.9; range: 4-141) who underwent externalization of deep brain electrodes prior to full internalization. A total of 21 studies (91.3%) reported follow-up times (mean: 36.5 mo; range: 3-180 mo). In total, 10 out of the 23 studies mentioned the use of antibiotic prophylaxis before surgery as well as during the period of externalization. Among those studies that distinguished the diagnosis of their patients who underwent externalization, 594 (48.4%) underwent DBS for PD, 430 (35.0%) for pain, 104 (8.5%) for dystonia, 64 (5.2%) for tremor, 11 for multiple sclerosis (0.9%), 8 (0.7%) for Tourette syndrome, 7 (0.6%) for major depressive disorder, 4 (0.3%) for epilepsy, 4 (0.3%) for Prader-Willi syndrome, and 2 (0.2%) for Huntington disease. Duration of externalization mostly ranged from 1 to 7 d, with the exception of 1 study that included some patients who were externalized for more than 7 d.32 A total of 14 studies were retrospective in design and 9 were prospective. Only 3 studies (15.4% of patients) included a control group of patients who were not externalized. Although many studies provided a detailed account of infectious disease history, only 2 studies (8.7%) referenced a specific definition or criteria by which infection was diagnosed.

Main Findings

The main findings of the included studies can be found in Table 3. A total of 82 patients (6.1%) were diagnosed with 91 infections following lead externalization, with rates of infection ranging between 0% and 50%. The rate of infection was 5.6% in retrospective studies and 7.8% in prospective studies. Studies with an externalization period of strictly <7 d27,34,35,38,40,41,43,46 had a rate of infection (20/358 [5.6%]) that was slightly less than the rate of infection in studies with an externalization period of ≥7 d (30/510 [5.9%]).11,26,28,32,37,39,42,45 Average time to infection was 4.6 mo (range: 0.5-10.2); however, only 7 studies reported this information. The indication with the highest rate of infection after DBS surgery was Prader-Willi syndrome (2/4 [50.0%]), followed by major depressive disorder (1/7 [14.3%]), Tourette syndrome (1/8 [12.5%]), pain (39/430 [9.1%]), PD (25/594 [4.2%]), dystonia (4/104 [3.8%]), and tremor (2/64 [3.1%]). The overall rate of infection for patients with movement disorders (PD, tremor, and dystonia) was 4.1% (31/762 patients). Patients who underwent DBS for multiple sclerosis (11 patients), epilepsy (4 patients), or Huntington disease (2 patients) did not have any infections.

In those studies that localized the site of infection, 26 (38.8%) were on the scalp overlying the burr hole, 25 (37.3%) were at the IPG, 12 (17.9%) were on the scalp overlying the connecting cable, 2 were intracranial at the site of lead, and 3 infections involved more than 1 site. A total of 7 studies noted positive findings on bacterial culture. The most common pathogens identified included Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis. In those studies that described management of infection, all but 2 studies (89.5%) reported removal of hardware as a form of management. In total, 3 studies22,28,33 concluded that there was no increased risk of infection with externalization and 1 study concluded otherwise.38

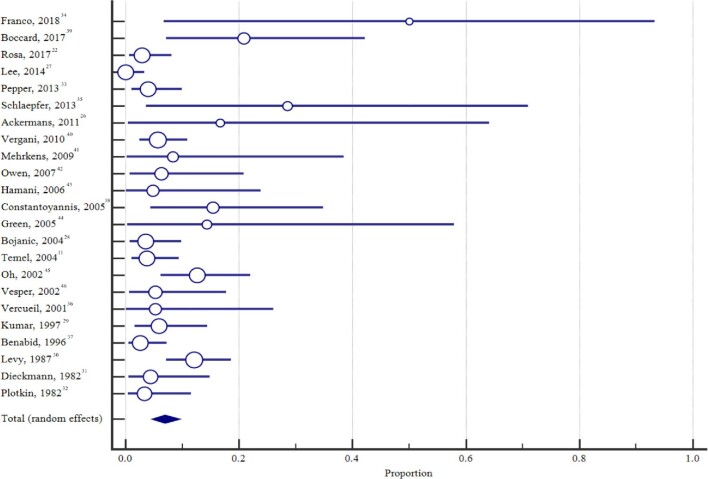

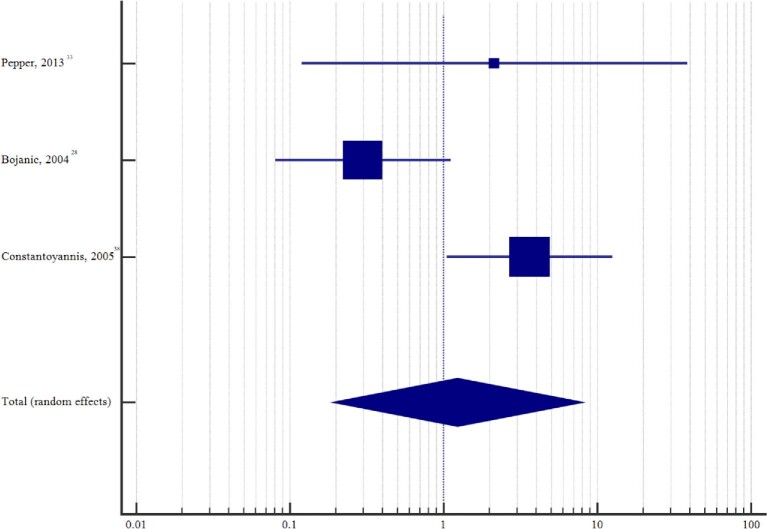

Meta-Analysis

The pooled proportion of externalized patients that developed an infection was 6.9% (95% CI: 4.7%-9.5%) (Figure 2). Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 measure of inconsistency and was found to be 62.2% (95% CI: 40.7-75.9; P < .0001), consistent with a moderate to high level of heterogeneity. Among those studies with a nonexternalized control group, the pooled relative risk estimate for infection in patients with an externalization period was 1.2 (95% CI: 0.2-8.0; P = .825) (Figure 3), with moderate to high level of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 73.9% [95% CI: 12.8-92.2]; P = .022). Unfortunately, this analysis was inadequately powered to detect if there was no difference in the incidence of infection between patients who underwent externalization and those that did not.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of pooled estimate of infection across all studies.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of the relative risk of infection among studies with a nonexternalized control group.

When determining whether study design (retrospective vs prospective) had an effect on the rate of infection, metaregression analysis found that difference between the 2 groups was statistically nonsignificant (P = .681). Similarly, metaregression analysis found that the rate of infection was not significantly different (P = .277) between studies with a duration of externalization <7 d and those with a duration of externalization of ≥7 d.

DISCUSSION

Key Results and Comparison with the Literature

The externalization of deep brain electrodes provides the opportunity to test the efficacy of DBS for new indications and to acquire neurophysiological data. As with any medical intervention it is critical that patients have sufficient understanding of the risks of the intervention prior to consenting to treatment. Here, we found that the average rate of infection for individuals who undergo an externalization prior to full DBS system implantation is 6.9%.

There is substantial variation in the published incidence of infection following DBS, with rates ranging from approximately 1.5% to 22.2%.4-21 Previous systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses on DBS-related infections have calculated rates of infection ranging between 4.7% and 6.1%2,3,52; however, comparing our results with that of published estimates is problematic because of differences in study design, population, and follow-up time in the included articles. In particular, a large proportion (35.0%) of the patients that underwent externalization were patients that were being treated for pain, which appears to be an indication that is more susceptible to infection (9.1% rate of infection) than that of other indications for DBS such as PD (4.2% risk of infection). In contrast, patients who underwent DBS for pain are generally not represented in the previously published meta-analyses, which mostly comprise studies with no period of externalization.2,3,52 Given that there are known differences in infection rate based on the indication for DBS,2,53 we can compare infection rates based on underlying disease. In their systematic review of hardware-related complications of DBS, Jitkritsadakul et al2 identified 96 articles, comprising 8983 patients that met their selection criteria. They found that established indications for DBS, such as PD (5.8% rate of infection), had lower rates of hardware-related infection, than that of new indications for DBS, such as Tourette syndrome (11.7% rate of infection).2 Consistent with these results, we found that patients that were externalized prior to permanent DBS implantation for movement disorders such as PD (4.2% rate of infection) and tremor (3.1% rate of infection) had lower rates of infection than patients treated for psychiatric diseases, such as Tourette syndrome (12.5%) and major depressive disorder (14.3%) (Table 4). Overall, when considering just those patients that underwent externalization prior to DBS implantation for movement disorders (PD, tremor, and dystonia), we found that the incidence of infection in these patients (4.1%) was less than the 4.7% average rate of infection reported by Bhatia and colleagues3 in their meta-analysis of infections for movement disorders.

TABLE 4.

Rates of Infection by Indication: Comparing Our Results With the Literature

| DBS indication | Rate of infection with externalization, % (infection/total) | Rate of infection from the literature, % (infection/total)a |

|---|---|---|

| PD | 4.2 (25/594) | 5.8 (85/1454) |

| Pain | 9.1 (39/430) | INS |

| Dystonia | 3.8 (4/104) | 7.4 (44/592) |

| Tremor | 3.1 (2/64) | INS |

| MS | 0 (0/11) | INS |

| TS | 12.5 (1/8) | 11.7 (16/137) |

| MDD | 14.3 (1/7) | INS |

| Epilepsy | 0 (0/4) | 11.5 (16/139) |

| HD | 0 (0/2) | INS |

| PWS | 50 (2/4) | INS |

DBS, deep brain stimulation; PD, Parkinson disease; INS, information not supplied; MS, multiple sclerosis; TS, Tourette syndrome; MDD, major depressive disorder; HD, Huntington disease; PWS, Prader-Willi syndrome.

Literature rates of infection as reported by Jitkritsadakul et al2 in their review of hardware-related complications of DBS.

Studies with a Control Group of Nonexternalized Patients

In order to further assess whether a period of externalization contributes to an increased risk of infection, we performed an additional meta-analysis on 3 studies that included a control group of patients that did not undergo a period of externalization (Table 5).28,33,38 Although rates of infection between the 2 groups were similar (5.2% for those externalized vs 6.0% for those nonexternalized), the meta-analysis was inadequately powered and therefore at high risk of a Type II error.54 A comparison with larger sample sizes will be needed to sufficiently determine if there is in fact no significant difference in infection between the 2 groups.

TABLE 5.

Outcomes of Studies With an Externalized and Nonexternalized Group

| Author, year | Infected/externalized (%) | DBS indication of infected (%) | Site of infection (%) | Infected/nonexternalized (%) | DBS indication of infected (%) | Site of infection (%) | Increased risk with externalization? (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pepper, 201334 | 4/100 (4.0%) | 3 PD (INS); 1 tremor (INS) | IPG (25%), IPG and BH (25%), BH (50%) | 0/23 (0%) | NA | NA | No (.78) |

| Constantoyannis, 200539 | 4/26 (15.3%) | INS | INS | 5/118 (4.2%) | INS | INS | Yes (.003) |

| Bojanic, 200429 | 3/86 (3.5%) | 3 pain (18.8%) | IPG (100%) | 7/60 (11.7%) | 3 PD (13.0%); 4 dystonia (19.0%) | IPG (100%) | No (<.099) |

BH, on scalp overlying burr hole; DBS, deep brain stimulation; INS, information not supplied; IPG, internal pulse generator; NA, not applicable; PD, Parkinson disease.

The most common location of infection for the nonexternalized patients was at the site of the IPG (specified in 7/7 patients), which is consistent with previously published studies.2,52 Similarly, in their series of 420 patients who underwent DBS without any externalization period, Sillay and colleagues6 reported that 14 out of 19 patients with infection (73.7%) had their infection located at the site of the IPG. In contrast, across all 23 of our included studies, almost equal numbers of infection were reported at the IPG (37.3%) and the scalp overlying the burr hole (38.8%) in patients who underwent an externalization period. This may suggest that although the process of electrode externalization may not confer an increased risk of infection compared to direct internalization, it does seem to influence the site of infection, possibly increasing the relative risk of cranial site infections.

Infection Rates for Commonly Externalized Devices in Neurosurgery

The externalization of therapeutic and monitoring devices is well-established in neurosurgical practice. Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring and external ventricular drains (EVDs) are fundamental to the care of patients in the neurocritical setting but are not without risk. Infection is the most common complication encountered with ICP monitors, with an average rate of infection of 10%.55 Although fiberoptic ICP monitors are associated with a decreased rate of infection,56 EVDs, considered the “gold standard” of ICP monitoring, have been found to be associated with an 8.8% average rate of infection.57 The most recent study on this topic reported a 3.1% infection rate among 389 consecutive patients who underwent EVD placement.58 In the subspecialty of functional neurosurgery, the technique of electrode externalization is already commonly used for monitoring seizure activity in patients with epilepsy, often for weeks at a time. The complications of this procedure are not negligible, with reported rates of infection ranging between 2% and 10%.59

Limitations

This is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of electrode externalization and its associated rates of infection. Because few studies have explicitly investigated the risk of electrode externalization, the majority of our data was extracted from retrospective case series with no control group, varying sample sizes, and follow-up times. Although we provide a comparative analysis from studies that included comparator groups, the comparison of infection rates should be interpreted with caution as the number of subjects is small and the effect size is likely small, limiting the power of this comparison and predisposing to Type II error. Larger sample sizes are needed in order to determine if there is in fact a significant difference in infection rate between the groups. Moreover, the profile of patients evaluated in our pooled analysis does not reflect the overall profile of patients who undergo DBS implantation, with a predominant indication for PD. In the pooled data, 35% of externalized patients had pain, 0.7% had Tourette syndrome, and 0.3% had Prader-Willi syndrome, which are not established DBS indications and are associated with skin picking,60,61 which may in and of itself change the relative risk of infection. Additionally, studies varied in their use of antibiotic prophylaxis as well as their definition of infection. Despite these limitations, our study serves as an important starting point for understanding the risk of infection with externalization and its comparison to nonexternalized cohorts.

CONCLUSION

The results of our systematic review and meta-analysis found a 6.9% risk of infection with externalization of deep brain electrodes, which is comparable to the historical rate of infection for individuals without an externalization period. Although this is the best estimate currently available, further research is needed before this information can be confidently used in the clinical setting.

Funding

This work is supported in part by NIH/NINDS grants to Dr Pouratian (R01NS097882 and UH3NS103549) and Dr Sheth (UH3NS103549). No funding was received from commercial or not-for-profit sectors for this work.

Disclosures

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article. Drs Pouratian and Sheth are consultants for Abbott and Boston Scientific.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Alon Kashanian, Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Pratik Rohatgi, Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Srinivas Chivukula, Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Sameer A Sheth, Department of Neurosurgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

Nader Pouratian, Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Supplemental Digital Content. Text. Appendix A, Literature review search strategy. Appendix B, Articles excluded and reasons for exclusion after full-text review.

COMMENT

This metanalysis reflects the great work by its authors, who effectively analyzed the data from the literature about the infection rate after the externalization of DBS electrode. As noted by the authors, certain limitations may affect the conclusion, however the literature review and analysis results are very comprehensive and well conducted, and it is an excellent addition to the current literature. The infection rate remained variable from center to center. In general, the incidence of infection can be reduced by the applied surgical techniques, whether in DBS or spinal cord stimulation. The pacemaker location remains the leading site of DBS infection. Furthermore, pacemaker replacement is shown to carry a higher risk of infection than a primary DBS system implant, and this can be reduced by surgical technique modification.1

In the context of DBS electrode externalization various benefits, this current study well supports the safety of its utilization. Throughout history, the science of brain stimulation has benefited significantly from studying the biomarkers of deep brain neuronal structures after a period of the externalized electrode. Enabling scientists to probe different neural circuits has resulted in the advancement of the science in various neurological and functional disorders. The technology advancement is directed toward a wireless technology that could replace the need for deep brain electrode externalization. Many thanks to the authors for providing such a comprehensive, detailed review and analysis.

Faisal Alotaibi

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Reference

- 1. Pepper J, Meliak L, Akram H, et al. Changing of the guard: reducing infection when replacing neural pacemakers. J Neurosurg. 2017;126(4):1165-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

- 1. Cagnan H, Denison T, McIntyre C, Brown P. Emerging technologies for improved deep brain stimulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(9):1024-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jitkritsadakul O, Bhidayasiri R, Kalia SKet al. . Systematic review of hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation: do new indications pose an increased risk? Brain Stimul. 2017;10(5):967-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhatia R, Dalton A, Richards Met al. . The incidence of deep brain stimulator hardware infection: the effect of change in antibiotic prophylaxis regimen and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25(5):625-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Putzke JD, Wharen RE, Wszolek ZKet al. . Thalamic deep brain stimulation for tremor-predominant Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2003;10(2):81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seijo FJ, Alvarez-Vega MA, Gutierrez JCet al. . Complications in subthalamic nucleus stimulation surgery for treatment of Parkinson's disease. Review of 272 procedures. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149(9):867-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sillay KA, Larson PS, Starr PA. Deep brain stimulator hardware-related infections: incidence and management in a large series. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(2):360-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sorar M, Hanalioglu S, Kocer Bet al. . Experience reduces surgical and hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation surgery: a single-center study of 181 patients operated in six years. Parkinsons Dis. 2018;2018:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Umemura A, Jaggi JL, Hurtig HIet al. . Deep brain stimulation for movement disorders: morbidity and mortality in 109 patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(4):779-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lyons KE, Wilkinson SB, Overman J, Pahwa R. Surgical and hardware complications of subthalamic stimulation: a series of 160 procedures. Neurology. 2004;63(4):612-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kondziolka D, Whiting D, Germanwala A, Oh M. Hardware-related complications after placement of thalamic deep brain stimulator systems. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79(3-4):228-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Temel Y, Ackermans L, Celik Het al. . Management of hardware infections following deep brain stimulation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2004;146(4):355-361; discussion 361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benabid AL, Benazzouz A, Hoffmann Det al. . Long-term electrical inhibition of deep brain targets in movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2008;13(S3):119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollak P, Fraix V, Krack Pet al. . Treatment results: Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(S3):S75-S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Movement Disorder Group, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: evidence for effectiveness and limitations from 12 years’ experience. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(6):474-480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gervais-Bernard H, Xie-Brustolin J, Mertens Pet al. . Bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in advanced Parkinson's disease: five year follow-up. J Neurol. 2009;256(2):225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeLong MR, Huang KT, Gallis Jet al. . Effect of advancing age on outcomes of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(10):1290-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Petraglia FW, Farber SH, Han JLet al. . Comparison of bilateral vs staged unilateral deep brain stimulation (DBS) in Parkinson's disease in patients under 70 years of age. Neuromodulation. 2016;19(1):31-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Obeso JA. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 1998;13(Suppl 2):S303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fily F, Haegelen C, Tattevin Pet al. . Deep brain stimulation hardware-related infections: a report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(8):1020-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piacentino M, Pilleri M, Bartolomei L. Hardware-related infections after deep brain stimulation surgery: review of incidence, severity and management in 212 single-center procedures in the first year after implantation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011;153(12):2337-2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Voges J, Waerzeggers Y, Maarouf Met al. . Deep-brain stimulation: long-term analysis of complications caused by hardware and surgery-experiences from a single centre. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(7):868-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosa M, Scelzo E, Locatelli Met al. . Risk of infection after local field potential recording from externalized deep brain stimulation leads in Parkinson's disease. World Neurosurg. 2017;97:64-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff Jet al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engel K, Huckhagel T, Gulberti Aet al. . Towards unambiguous reporting of complications related to deep brain stimulation surgery: a retrospective single-center analysis and systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0198529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rutka JT. Editorial. Classes of evidence in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2016;126(6):1747-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ackermans L, Duits A, van der Linden Cet al. . Double-blind clinical trial of thalamic stimulation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2011;134(pt 3):832-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee S-W, Lee M-K, Seo Iet al. . A groove technique for securing an electrode connector on the cranial bone: case analysis of efficacy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;56(2):130-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bojanic S, Sethi H, Hyam Jet al. . Externalising deep brain electrodes: an increased risk of infection? J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11(7):732-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kumar K, Toth C, Nath RK. Deep brain stimulation for intractable pain: a 15-year experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(4):736-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levy RM, Lamb S, Adams JE. Treatment of chronic pain by deep brain stimulation: long term follow-up and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;21(6):885-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dieckmann G, Witzmann A.. Initial and long-term results of deep brain stimulation for chronic intractable pain. Appl Neurophysiol. 1982;45(1-2):167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Plotkin R. Results in 60 cases of deep brain stimulation for chronic intractable pain. Appl Neurophysiol. 1982;45(1-2):173-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pepper J, Zrinzo L, Mirza Bet al. . The risk of hardware infection in deep brain stimulation surgery is greater at impulse generator replacement than at the primary procedure. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2013;91(1):56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Franco RR, Fonoff ET, Alvarenga PGet al. . Assessment of safety and outcome of lateral hypothalamic deep brain stimulation for obesity in a small series of patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e185275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schlaepfer TE, Bewernick BH, Kayser Set al. . Rapid effects of deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1204-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vercueil L, Pollak P, Fraix Vet al. . Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of severe dystonia. J Neurol. 2001;248(8):695-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Benabid AL, Pollak P, Gao DMet al. . Chronic electrical stimulation of the ventralis intermedius nucleus of the thalamus as a treatment of movement disorders. J Neurosurg. 1996;84(2):203-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Constantoyannis C, Berk C, Honey CRet al. . Reducing hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32(2):194-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boccard SGJ, Prangnell SJ, Pycroft Let al. . Long-term results of deep brain stimulation of the anterior cingulate cortex for neuropathic pain. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:625-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vergani F, Landi A, Pirillo Det al. . Surgical, medical, and hardware adverse events in a series of 141 patients undergoing subthalamic deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease. World Neurosurg. 2010;73(4):338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mehrkens JH, Botzel K, Steude Uet al. . Long-term efficacy and safety of chronic globus pallidus internus stimulation in different types of primary dystonia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87(1):8-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Owen SLF, Green AL, Nandi DDet al. . Deep brain stimulation for neuropathic pain. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97(pt 2):111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hamani C, Schwalb JM, Rezai ARet al. . Deep brain stimulation for chronic neuropathic pain: long-term outcome and the incidence of insertional effect. Pain. 2006;125(1-2):188-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Green AL, Owen SLF, Davies Pet al. . Deep brain stimulation for neuropathic cephalalgia. Cephalalgia. 2005;26(5):561-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oh MY, Abosch A, Kim SHet al. . Long-term hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(6):1266-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vesper J, Klostermann F, Stockhammer Fet al. . Results of chronic subthalamic nucleus stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a 1-year follow-up study. Surg Neurol. 2002;57(5):303-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Freeman MF, Tukey JW.. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607-611. [Google Scholar]

- 48. DerSimonian R, Laird N.. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mantel N, Haenszel W.. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719-748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Borenstein M, Hedges L V, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hamani C, Lozano AM.. Hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation: a review of the published literature. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2006;84(5-6):248-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Falowski SM, Ooi YC, Bakay RAE. Long-term evaluation of changes in operative technique and hardware-related complications with deep brain stimulation. Neuromodulation. 2015;18(8):670-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sullivan GM, Feinn R.. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):279-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rebuck JA, Murry KR, Rhoney DHet al. . Infection related to intracranial pressure monitors in adults: analysis of risk factors and antibiotic prophylaxis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(3):381-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Raboel PH, Bartek J, Andresen Met al. . Intracranial pressure monitoring: invasive versus non-invasive methods—a review. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lozier AP, Sciacca RR, Romagnoli MF, Connolly ES. Ventriculostomy-related infections: a critical review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(1):170-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sweid A, Weinberg JH, Abbas Ret al. . Predictors of ventriculostomy infection in a large single-center cohort. J Neurosurg. 2020;1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Skoch J, Adelson PD, Bhatia Set al. . Subdural grid and depth electrode monitoring in pediatric patients. Epilepsia. 2017;58(Suppl 1):56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Greenberg E, Tung ES, Gauvin Cet al. . Prevalence and predictors of hair pulling disorder and excoriation disorder in Tourette syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(5):569-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Whittington J, Holland A. Developing an understanding of skin picking in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: a structured literature review and re-analysis of existing data. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;112:48-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.