Abstract

1,4-Thiazepanes and 1,4-thiazepanones represent seven-membered ring systems with highly 3D character and are currently underrepresented in fragment screening libraries. A nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) fragment screen identified 1,4-acylthiazepanes as new BET (bromodomain and extraterminal domain) bromodomain ligands; however, an efficient and readily diversified synthesis for library development has not been reported. Here we report a one-pot synthesis using α,β-unsaturated esters and 1,2-amino thiols to form 1,4-thiazepanones as precursors to 1,4-thiazepanes with high 3D character. This reaction proceeds in reasonable time (0.5−3 h) and in good yield and tolerates a broad scope of α,β-unsaturated esters. Several 1,4-thiazepanes were synthesized by a two-step transformation and were characterized as new BET bromodomain ligands using protein-observed 19F NMR. This synthesis should provide ready access to diverse 3D fragments for screening libraries.

Graphical Abstract

Fragment-based ligand discovery (FBLD) is an efficient approach for inhibitor discovery against difficult drug targets.1 The premise of FBLD is a reduction of chemical space that is efficiently sampled through screening low-molecular weight molecules. Retrospective analyses identified a need for increasing the fragment library diversity.2 Fragment libraries are largely composed of flat molecular scaffolds, with a high prevalence of aromatic rings.3,4 Ring systems, such as saturated seven-membered rings, are underrepresented.5 Fragments with increased 3D character have shown improved specificity in protein-binding assays, offering an additional metric for library design.6 We recently screened a 3D-enriched library against the protein, BRD4,7 an anticancer drug target.8,9 One lead 3D fragment hit, 1a, was an acylated 1,4-thiazepane. The structure−activity relationship (SAR) study was limited due to the lack of a robust and easily diversified synthetic route for creating a library of thiazepane molecules. To address this need, we report an optimized synthesis of 1,4-thiazepanes for fragment library development (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

General scheme for 1,4-thiazepanone and 1,4-thiazepane synthesis.

We sought to establish a high-yielding synthesis of 1,4-thiazepane and thiazepanones for BRD4 inhibitor development. Whereas multiple approaches have been described for forming benzothiazepinones,10–13 which benefit from the rigidified amino thiols for optimizing cyclization, far fewer methods for non-ring-fused thiazepanones are reported (Figure 1, top). Tetrahydro-1,4-thiapyranones undergo Beckmann rearrangements14,15 or Schmidt reactions.16,17 These pathways yield the desired seven-membered rings, but access to starting materials for library synthesis and undesired regioisomer production18 hinder their effectiveness. Conjugate additions into α,β-unsaturated lactones and lactams yield 1,4-thiazepanones, but these methods force hydroxyl or amino substituents in the seven-position, limiting the scope for product diversity.19 Methyl-3-mercaptopropionate cyclizes using aziridine with sodium methoxide. This pathway requires several days and may not be compatible with base-sensitive functional groups.20,21 Thiazepanones are also synthesized from cyclization with cysteamine or derivatives under basic conditions with α,β-unsaturated esters, taking 3−7 days and often resulting in low yield.21−25 Our synthesis of 1a using this approach gave similar yields (32%) and reaction time (3 days).7 Here we develop cysteamine cyclization reactions with α,β-unsaturated esters to produce 1,4-thiazepanones in short (<3 h) reaction times (Figure 1, bottom). The significant improvement stems from the moderate reactivity of trifluoroethyl esters and milder reaction conditions to increase the substrate scope. Using our improved conditions, a broad scope of 1,4-thiazepanones is achieved, in many cases without chromatography. These thiazepanones are subsequently reduced and functionalized to generate bromodomain ligands.

Our initial attempt to synthesize the 1,4-thiazepanone included a two-step reaction, creating an amide bond with aryl-substituted acrylic acids, followed by an intramolecular conjugate addition (Scheme S2). Here the conjugate addition step was not successful, presumably due to the reduced electrophilicity of the β-carbon. Conducting the conjugate addition first on 3-(2-thienyl)acrylic acid with N-Boc-cysteamine, followed by deprotection and intramolecular acylation to form 3a led to a mixture of side products. We ultimately focused our attempts instead on a one-pot conjugate addition and acylation reaction (Figure 1).

The initial optimization of the tandem conjugate addition/cyclization reaction used the methyl ester of 3-(2-thienyl)-acrylic acid to favor conjugate addition prior to cyclization. A base screen showed DBU to yield the cyclized 1,4-thiazepanone, albeit in low yields (11%, Table 1). Other bases, DIEA, Et3N, and NaOH, did not yield product. NaOH has been previously used; however, the reaction times took 5 days with modest yield.24 Finally, we tested the effect of acyl transfer additives26 and found 0.2 equiv of imidazole to increase the yield (53%, entry 5, Table 1). The reaction was further improved through solvent choice. Tetrahydrofuran and acetonitrile were well-suited for this reaction. Acetonitrile was optimal, as the reaction worked efficiently at ambient temperature (entry 9) and excluded the need for heating to solubilize reagents, as required for tetrahydrofuran.

Table 1.

Reaction Optimization with Solvent and Basea

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | base | time (h) | % yield | temp (°C) | imidazole | solvent |

| 1 | Et3N | 18 | 0 | 60 | no | THF |

| 2 | DIEA | 18 | 0 | 60 | no | THF |

| 3 | NaOH | 18 | 0 | 60 | no | THF |

| 4 | DBU | 18 | 11 | 60 | no | THF |

| 5 | DBU | 18 | 53 | 60 | yes | THF |

| 6 | DBU | 24 | 25 | 60 | no | CH3OH |

| 7 | DBU | 18 | 27 | 60 | no | DMF |

| 8 | DBU | 18 | 53 | 60 | yes | CH3CN |

| 9 | DBU | 18 | 56 | rt | yes | CH3CN |

Reactions performed with 2a.1 (1.0 equiv), cysteamine (1.2 equiv), base (2.0 equiv), and imidazole (0–20 mol %) in solvent (5 mL). Yields and temperature indicated.

Finally, we sought to tune the electrophilicity of the α,β-unsaturated esters while favoring conjugate addition before acylation. We tested methyl (2a.1), 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl (2a.2), and hexafluoroisopropyl (2a.3) esters (Table 2).27 Ester 2a.2 was the best-suited, yielding 3a in higher yields (70%, entry 4, Table 2) and shorter reaction times (0.5 h) relative to the much slower methyl ester (56%, entry 1, 18 h). Under these conditions, alternative bases could be used but with reduced yield or extended reaction times. Unlike the methyl ester, the trifluoroethyl ester cyclization worked efficiently, forming thiazepanone 3a without imidazole (71%, entry 5, Table 2).

Table 2.

Optimization of Cyclization for 1,4-Thiazepanonesa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | base | time (h) | % yield | imidazole |

| 1 | –CH3 (2a.1) | DBU | 18 | 56 | yes |

| 2 | –CH2CF3 (2a.2) | DIEA | 18 | 71 | yes |

| 3 | –CH2CF3 (2a.2) | NaOH | 18 | 22 | yes |

| 4 | –CH2CF3 (2a.2) | DBU | 0.5 | 70 | yes |

| 5 | –CH2CF3 (2a.2) | DBU | 0.5 | 71 | no |

| 6 | –CH(CF3)2 (2a.3) | DBU | 1 | 50 | yes |

Reactions performed with ester (1 equiv), cysteamine (1.2 equiv), base (2 equiv), and imidazole (0–20 mol %) in CH3CN (5 mL) at rt for 0.5–18 h. Yields are indicated.

Under these optimized conditions, we tested the order of the two-step reaction sequence. When the ester group was replaced by an amide via first acylating with cysteamine, the subsequent conjugate addition product was not formed using the optimized conditions. (Scheme S2).28 This result is consistent with conjugate addition preceding cyclization when using the trifluoroethyl ester.

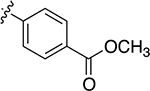

With a set of conditions in hand, we explored the reaction scope with respect to the α,β-unsaturated ester (Table 3). In the case of cinnamic esters, the syntheses worked efficiently. For para substitution, electron-donating and -withdrawing groups led to isolated yields of 50−83% for 3f−k. For p-nitro groups, reduced yields and increased side products were obtained. The yield of 3l could be improved to 40% by excluding the acyl transfer catalyst or by using the less reactive methyl ester. Ortho- and meta-substituted cinnamic esters provided modest to high yields of 50−87% (e.g., 3m−o) and trisubstituted α,β-unsaturated esters 3p and 3s. High-yielding reactions (i.e., 3f, 3g, 3h, 3j, 3m, and 3n) did not require chromatographic purification. A few reactions showed modest conversion of 50% (3i and the disubstituted aryl ether 3t) primarily due to unreacted cinnamic ester, even after several hours of reaction. For the heterocyclic substituent nitrofuryl-containing 3d, the reaction did not form the major product. Alternatively, 3d was obtained using the less reactive methyl ester but in low yield. Imidazole-containing ester was nonreactive toward these conditions to form 3e, indicating sensitivity toward more electron-deficient heterocycles. α,β-Unsaturated esters substituted without aromatic groups are also substrates and yield 3q and 3r in comparable yield.

Table 3.

Scope of Cyclization for 1,4-Thiazepanonesa

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | time | yield | compd | R1 | time | yield |

| 3a |  |

0.5 h | 70% | 3m |  |

1 h | 87% |

| 3b |  |

1 h | 70%b | 3n |  |

1 h | 81% |

| 3c |  |

3 h | 69% | 3o |  |

1 h | 77% |

| 3d |  |

1 h | 0, 18%c | 3p |  |

1.5 h | 56% |

| 3e |  |

1 h | 0% | 3q |  |

1 h | 84% |

| 3f |  |

2 h | 78% | 3r |  |

1 h | 56% |

| 3g |  |

1 h | 82% | 3s |  |

3 h | 62%d |

| 3h |  |

1 h | 83% | 3t |  |

2 h | 50% |

| 3i |  |

1 h | 50% | 3u |  |

3 h | 66% |

| 3j |  |

0.5 h | 61% | 3v |  |

3 h | 31% |

| 3k |  |

0.5 h | 65% | 3w |  |

1 h | 65% |

| 3l |  |

0.5 h | 40%b | ||||

Reactions performed with ester (1.0 equiv), cysteamine (1.2 equiv), base (2 equiv), and imidazole (0–20 mol %) in CH3CN (5 mL) at rt, 0.5–3 h. Yields indicated.

Product obtained using methyl ester and no imidazole.

No imidazole was added.

Product isolated as a diastereomeric mixture; R2 = CH3

Finally, we tested polar and acid- and base-sensitive functional groups. Thiazepanones with acid- or base-labile protecting groups, Boc and trifluoroacetamide, respectively, also formed (3w, 3v). A methyl ester was also tolerated (3u). In contrast, previously reported protocols using either strongly basic or acidic conditions provide limited access to these acid- or base-labile functional groups.20−25

We next tested the generality of this reaction using cysteine, penicillamine, and 1,4-aminothiophenol (Table 4).22 For cysteine derivatives, the free carboxylic acid was converted to a methyl ester prior to isolation to yield 3x and 3y. A moderate to high degree of diastereoselectivity was observed (i.e., 3x, dr = 2.3:1; 3y, dr = >95:1). Additionally, we reacted 2-aminothiophenol with either a trifluoroethyl or a methyl ester of cinnamic acids. The reaction was unsuccessful with predominant disulfide formation. Alternately, compound 3c.1 was synthesized via a reported protocol using TBAF as a catalyst under neat conditions.29 In our hands, these conditions were not compatible with the synthesis of non-ring-fused 1,4-thiazepanones, demonstrating the complementary nature of both methods.

Table 4.

Cyclization with Different 1,2-Aminothiolsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | compd | 1,2-aminothiol | base/catalyst | time (h) | % yield |

| 1 | 3x | l-cysteine | DBU | 18 | 67b |

| 2 | 3y | l-penicillamine | DBU | 18 | 62b |

| 3 | 3a.1 | 2-aminothiophenol | DBU | 18 | 0c |

| 4 | 3c.1 | 2-aminothiophenol | TBAF | 24 | 65d |

For 3x and 3y, reactions were performed with 1.0 equiv of ester, 1,2-aminothiol (1.2 equiv), base (2 equiv), dimethylsulfate (1.5 equiv), and imidazole (0–20 mol %) in CH3CN (5 mL). For 3c.1, the reaction was performed with cinnamic acid (1 equiv), 2-amino-thiophenol (2 equiv), and TBAF (0.1 equiv) at 80 °C for 24 h. Yields indicated.

Obtained as a mixture of diastereomers.

Predominant disulfide formation under optimized conditions.

Synthesized using the previously reported protocol.29

To produce 1,4-thiazepanes for bromodomain inhibition experiments, the 1,4-thiazepanones 3a, 3c, 3g, and 3h were reduced using sodium borohydride/iodine (Table 5) or borane dimethylsulfide28 to the corresponding 1,4-thiazepanes 4a, 4c, 4g, and 4h and converted to carbamates or amides (Table 5 and Table S1).28 Using this approach, we significantly improved the prior synthesis of parent compound 1a over the reported synthesis.7 The current methodology should be preferable for the synthesis of 1,4-thiazepanes to other approaches with an improvement in time, yield, and scope.

Table 5.

Synthesis of 1,4-Thiazepanesa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R | yield (%) | compd | R1 | R2 | yield (%) |

| 4a |  |

80 | 1a |  |

-OMe | 49 |

| 4c |  |

85 | 5a |  |

-CH2CH3 | 63 |

| 4g |  |

89 | 6a |  |

-OCH2CH2CH3 | 49 |

| 4h |  |

54 | 7a |  |

-OCHCH=CH2 | 86 |

| 1g |  |

-OMe | 47 | |||

| 1h |  |

-OMe | 51 | |||

Reduction conditions: thiazepanone (1.0 equiv), NaBH4 (5 equiv), iodine (2 equiv) in THF (5 mL). Carbamoylation and acylation conditions: amine (1 equiv), triethylamine (1.2 to 1.5 equiv), and electrophile (1.2 to 1.5 equiv) for 0.5 to 2 h, rt. Yields indicated.

With several 1,4-thiazepanes and thiazepanones in hand, we tested for BRD4-D1 binding. These molecules possess a significant 3D character with a plane-of-best fit of 0.84 to 1.0 and 0.61 to 1.1, respectively (Table S2),31 above the threshold of 0.25 for describing a 3D fragment.6 We used 19F NMR to quantify ligand binding to fluorinated BRD4-D1 by measuring a change in chemical shift of a fluorinated tryptophan (W81) resonance located in the protein binding site (Figure 2B).30 We tested 11 compounds at a single concentration, including six thiazepanones and five thiazepanes. Thiazepanes 1g, 1h, and 6a induced a significant chemical shift and were titrated to obtain a Kd value of 120−210 μM (Figure 2 and Figures S1 and S2), demonstrating good affinity. These titration experiments also demonstrate the good water solubility of the thiazepane scaffold.

Figure 2.

(A) Fluorine NMR titration. (B) BRD4-D1 with the 5-fluorotrytophans labeled in blue (PDB ID: 3MXF). (C) Binding isotherm of 1g (black circles) and 1h (purple squares). (D) Structure and corresponding ligand affinities.

In conclusion, we report the efficient synthesis of 1,4-thiazepane and 1,4-thiazepanones with an improved substrate scope. Several thiazepanes maintain affinity for BRD4. Ready access to this scaffold will increase the diversity of 3D fragment screening libraries. The versatility of this short approach will be used for library generation for screening against diverse proteins and for improving binding efficiency to BRD4.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the NIH Biotechnology training grant 5T32GM008347-23 and the Masonic Cancer Center for funding.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): We have submitted a provisional patent on this work: Pomerantz, W. C. K.; Johnson, J.; Kirberger, S. E.; Pandey, A. Improved Synthesis of Substituted 1,4-Thiazepan-5-ones. UMN Provisional Patent 2020–042, filed 2019.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01230.

Full experimental details and spectral characterization data (PDF)

Contributor Information

Anil K. Pandey, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States

Steven E. Kirberger, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States

Jorden A. Johnson, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States

Jennifer R. Kimbrough, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

Danika K. D. Partridge, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States

William C. K. Pomerantz, Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Erlanson DA; Fesik SW; Hubbard RE; Jahnke W; Jhoti H Twenty Years on: The Impact of Fragments on Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15 (9), 605–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fuller N; Spadola L; Cowen S; Patel J; Schö H; Cao Q; McKenzie A; Edfeldt F; Rabow A; Goodnow R An Improved Model for Fragment-Based Lead Generation at AstraZeneca. Drug Discovery Today 2016, 21 (8), 1272–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Brown DG; Boström, J. Analysis of Past and Present Synthetic Methodologies on Medicinal Chemistry: Where Have All the New Reactions Gone? J. Med. Chem 2016, 59 (10), 4443–4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Feher M; Schmidt JM Property Distributions: Differences between Drugs, Natural Products, and Molecules from Combinatorial Chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci 2003, 43 (1), 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Giordanetto F; Jin C; Willmore L; Feher M; Shaw DE Fragment Hits: What Do They Look Like and How Do They Bind? J. Med. Chem 2019, 62 (7), 3381–3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Clemons PA; Bodycombe NE; Carrinski HA; Wilson JA; Shamji AF; Wagner BK; Koehler AN; Schreiber SL Small Molecules of Different Origins Have Distinct Distributions of Structural Complexity That Correlate with Protein-Binding Profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107 (44), 18787–18792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Johnson JA; Nicolaou CA; Kirberger SE; Pandey AK; Hu H; Pomerantz WCK Evaluating the Advantages of Using 3D-Enriched Fragments for Targeting BET Bromodomains. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2019, 10, 1648–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Smith SG; Zhou M-M The Bromodomain as an Acetyl-Lysine Reader Domain. In Chromatin Signaling and Diseases; Elsevier, 2016; pp 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Filippakopoulos P; Qi J; Picaud S; Shen Y; Smith WB; Fedorov O; Morse EM; Keates T; Hickman TT; Felletar I; Philpott M; Munro S; McKeown MR; Wang Y; Christie AL; West N; Cameron MJ; Schwartz B; Heightman TD; et al. Selective Inhibition of BET Bromodomains. Nature 2010, 468 (7327), 1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Meninno S; Volpe C; Lattanzi A Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Protecting-Group-Free 1,5-Benzothiazepines. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23 (19), 4547–4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fang C; Lu T; Zhu J; Sun K; Du D Formal [3 + 4] Annulation of α,β-Unsaturated Acyl Azoliums: Access to Enantioenriched N− H -Free 1,5-Benzothiazepines. Org. Lett 2017, 19 (13), 3470–3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fukata Y; Asano K; Matsubara S Facile Net Cycloaddition Approach to Optically Active 1,5-Benzothiazepines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (16), 5320–5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Troelsen NS; Shanina E; Gonzalez-Romero D; Danková D; Jensen ISA; Śniady KJ; Nami F; Zhang H; Rademacher C; Cuenda A; Gotfredsen CH; Clausen MH The 3F Library: Fluorinated Fsp 3 -Rich Fragments for Expeditious 19 F NMR Based Screening. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59 (6), 2204–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Barkenbus C; Diehl JF; Vogel GR The Beckmann Rearrangement of Some Heterocyclic Ketoximes. J. Org. Chem 1955, 20 (7), 871–874. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Shankaran K; Donnelly KL; Shah SK; Caldwell CG; Chen P; Hagmann WK; MacCoss M; Humes JL; Pacholok SG; Kelly TM; Grant SK; Wong KK Synthesis of Analogs of (1,4)-3- and 5-Imino Oxazepane, Thiazepane, and Diazepane as Inhibitors of Nitric Oxide Synthases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2004, 14 (23), 5907–5911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mull RP; Egbert ME; Dapero MR Guanidines with Antihypertensive Activity. J. Org. Chem 1960, 25 (11), 1953–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Evans PA; Modi DP Novel Approach to Lactams via (Triisopropylsilyl) Azidohydrin Formation and Photoinduced Schmidt Rearrangement. J. Org. Chem 1995, 60 (21), 6662–6663. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Szostak M; Yao L; Aubé J Cation-n Control of Regiochemistry of Intramolecular Schmidt Reactions En Route to Bridged Bicyclic Lactams. Org. Lett 2009, 11 (19), 4386–4389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bohrisch J; Faltz H; Paẗzel M; Liebscher J Chiral 1,4-Diazepinones and 1,4-Thiazepinones by Diastereoselective Ring Chain Transformation of α,β Unsaturated Lactones or Lactams. Tetrahedron 1994, 50 (36), 10701–10708. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jakob F; Schlack P 5-Oxo-1-Thia-4-Aza-Cycloheptan-Synthesen. Chem. Ber 1963, 96 (1), 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Arya VP; Kaul CL; Grewal RS; David J; Talwaker PK; Shesoy SJ Antihypertensive Agents: Part V* - Synthesis & Antihypertensive Activity of 3-Arylimino-2,3,5,6-Tetrahydro-4H-1,4-Thiazines & Related Cyclic Amidines. Indian J. Chem. B 1977, 15, 720–726. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Leonard NJ; Ning RY The Synthesis and Stereochemistry of Substituted 1,4-Thiazepines Related to the Penicillins. J. Org. Chem 1966, 31 (12), 3928–3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Blondeau P; Berse RGC; Gravel D Synthesis of Some Stable 7-Halo-1,4-Thiazepines. Potential Substituted Penam Precursors. Can. J. Chem 1971, 49, 3866–3876. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wamhoff H; Theis CH Perhydro-l,4-Thiazepin-5-Onen. Chem. Ber 1980, 113, 995–1009. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Karimova NM; Glazkov AA; Ignatenko AV; Kolomiets AF Addition of Thiols to Ethyl 4,4,4-Trifluorocrotonate. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2003, 52 (7), 1621–1622. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Yang X; Birman VB Acyl Transfer Catalysis with 1,2,4-Triazole Anion. Org. Lett. 2009, 11 (7), 1499–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fang X; Li J; Wang CJ Organocatalytic Asymmetric Sulfa-Michael Addition of Thiols to α,β-Unsaturated Hexafluoroisopropyl Esters: Expeditious Access to (R)-Thiazesim. Org. Lett. 2013, 15 (13), 3448–3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28). Refer to the Supporting Information.

- (29).Zhang P; Ye D; Chu Y An Efficient One-Pot Procedure for the Synthesis of 1,5-Benzothiazepinones Catalyzed by Tetrabutylammonium Fluoride (TBAF). Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57 (33), 3743–3745. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gee CT; Arntson KE; Urick AK; Mishra NK; Hawk LML; Wisniewski AJ; Pomerantz WCK Protein-Observed 19F-NMR for Fragment Screening, Affinity Quantification and Druggability Assessment. Nat. Protoc 2016, 11 (8), 1414–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Colomer I; Empson CJ; Craven P; Owen Z; Doveston RG; Churcher I; Marsden SP; Nelson A A Divergent Synthetic Approach to Diverse Molecular Scaffolds: Assessment of Lead-Likeness Using LLAMA, an Open-Access Computational Tool. Chem. Commun 2016, 52 (45), 7209–7212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.