Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) affects approximately 30 million people worldwide, and this number is predicted to triple by 2050 unless further discoveries facilitate the early detection and prevention of the disease. Computerized walkways for simultaneous assessment of motor-cognitive performance, known as a dual-task assessment, has been used to associate changes in gait characteristics to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with early-stage disease. However, to our best knowledge, there is no validated method to detect MCI using the collective analysis of these gait characteristics. In this paper, we develop a machine learning approach to analyze the gait data from the dual-task assessment in order to detect subjects with cognitive impairment from healthy individuals. We collected dual-task gait data from a computerized walkway of a total of 92 subjects with 31 healthy control (HC) and 61 MCI. Using support vector machine (SVM) and gradient tree boosting, we developed a classifier to differentiate MCI from HC subjects and compared the results with a paper-based questionnaire assessment that has been commonly used in clinical practice. SVM provided the highest accuracy of 77.17% with 81.97% sensitivity and 67.74% specificity. Our results indicate the potential of machine learning + dual-task assessment to enable early diagnosis of cognitive decline before it advances to dementia and AD, so that early intervention or prevention strategies can be initiated.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, Cognitive Impairment, Gait Performance, Dual-Task Assessment, Support Vector Machine, gradient tree boosting

I. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common causes of dementia, a neurodegenerative disorder in elderly with symptoms related to brain function impairment [1]. AD is one of the most prevalent causes of mortality in the United States, accounting for almost 4% of deaths nationwide. However, early diagnosis remains a difficult task.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is abnormal cognitive decline beyond expected decline of normal aging with an estimated community prevalence of 21% for those over age 65. The rate of progression to AD in people with MCI is an estimated 75%, which is much higher than the rate of 1% to 2% seen in general population [2]. Hence, identifying subjects with MCI could help in detecting early-stages of AD. In order to identify MCI subjects, patient interviews and questionnaires are typically used to estimate risk and rate of cognitive decline. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test is an example of a brief cognitive screening method used by clinicians to identify MCI. However, these paper-based assessments are lengthy and require specialized training for proper administration, which make it less practical for use in the typical medicine, neurology or geriatric practices. Additionally, these subjective tests have proved to be poor at identifying valid changes in individuals’ cognitive decline with early-stage disease, and may not accurately predict progression. As a result, AD remains undiagnosed until cases advance, where sufficient neuronal injury has occurred to the extent that reversal of the disease is unlikely.

Gait has shown to have a robust relationship with cognition [5]. The dual-task assessment using a computerized walkway has been used to detect MCI individuals, who are likely to progress to AD, by assessing the decline in gait performance from a “single-tasking” (e.g., walking) to “dual-tasking” (e.g., walking while subtracting) [6]. However, the work has mainly focused on associating changes in single gait characteristics with MCI [3]. For example, in [7], the authors find that changes in gait apraxia/ataxia, shuffling gait, and limbic discoordination are associated with cognitive decline. In another study, the increased support time has shown to be an indicator of cognitive decline [8]. In [9], stride-to-stride variability has been reported to associate with cognitive decline. These approaches mainly use statistical analysis approaches to identify the gait parameters that are significantly different between MCI and healthy control (HC) subjects, without providing an aggregated model to differentiate MCI subjects from HC ones. What is missing is a method that could translate the gait data from the dual-task assessments into a clinically actionable knowledge about an individuals’ cognitive state [4]. Developing a model for detection of MCI subjects could enable early diagnosis of cognitive decline before it advances to dementia and AD, so that early intervention or prevention strategies can be initiated.

Machine leaning has shown to be successful in detecting MCI subjects using different types of subjects’ data such as MRI, diffusion tensor imaging, and electroencephalogram (EEG) (reviewed in [10]). However, these methods rely on expensive clinical protocols to collect data with extensive infrastructure and specialized medical equipment. Up to our best knowledge, the advantage of the application machine learning on dual-task assessment data has to yet be explored. In this paper, we developed a classifier based on support vector machine (SVM) and gradient tree boosting to detect MCI subjects. The study design and data collection are described in Section II. Selection of the gait feature is explained in Section III. Training the gradient tree boosting and SVM algorithm is described in Section IV. The results are provided and discussed in Section V, and the paper is concluded in Section VI.

II. STUDY DESIGN AND DATA COLLECTION

A. Study Population

A total of 92 subjects (age: 74 ± 18) were recruited at the Comprehensive Center for Brain Health at Florida Atlantic University. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Florida Atlantic University and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Prior to the experiments, the subjects provided written informed consent. The study participants consisted of HC and MCI subjects. The HC group included health subjects with no sign of cognitive decline and subjective cognitive decline (SCD), who have reported the self-reported experience of worsening or more frequent confusion or memory loss without an MCI diagnosis. The distribution of the subjects in each group is provided in Table I.

TABLE I.

The subject demographics. Values are presented as n or mean±STD.

| Population | Subjects (#) | MoCA |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Control | 31 | 27 ± 2 |

| Healthy | 16 | 28 ± 1 |

| SCD | 15 | 26 ± 3 |

| MCI | 61 | 23 ± 3 |

The participants performed a MoCA test (out of 30). MoCA is a brief questionnaire with 30 questions to assess people for any abnormal cognitive decline. It takes approximately 10 to 12 minutes to complete and is normally performed by a trained examiner at cognitive assessment centers. Table I provides the average and standard deviation of the MoCA scores for each population in this study.

B. Computerized Walk-way

The participants performed a series of dual-task assessments as their gait characteristics were measured and recorded using on a pressure sensitive walkway. In this study, we used a walkway with 14 ft. long × 4 ft. wide from Zenomat (ProtoKinetics LLC). The Zenomat data processing system provides a wide range of gait features from pressure measurements. We selected 16 gait features according to the gait characteristics that have shown to be associated with cognitive decline [10]. For every time that a subject walks back and forth on the mat, we extracted these 16 gait features (listed in Table II). Some characteristics, such as step time, were used separately for the left and right foot.

TABLE II.

A computerized walkway was used to measure a total of 16 gait features as subjects walk in each trial.

| Feature | Velocity | Cadence | Step Time | Swing | Stance | Single Support | Double Support | Step Length | Stride Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L and R | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| # | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Total features | 16 | ||||||||

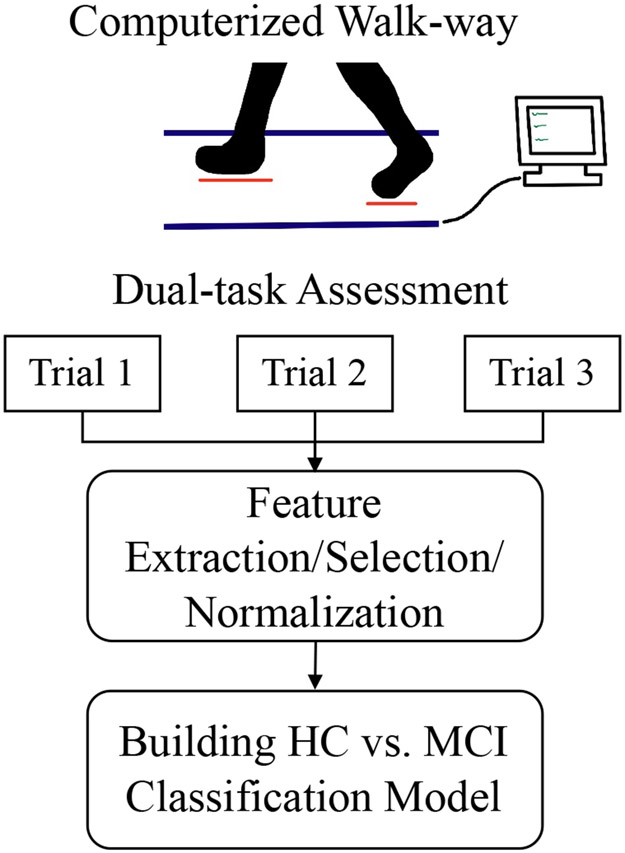

C. Dual-task Assessment

The experiments consisted of a total of three trials of gait with (1) no-cognitive load (i.e., single-tasking), (2) adding a cognitive load, and (3) increasing the cognitive load. The study started by trial 1 where the subjects walked on the computerized walkway. This will provide the baseline gait performance for each subject. Next, in trial 2, the subjects walked on the mat as they recited the alphabet. During trial 3, the subjects counted backwards by 3’s from 100 as walking. Gait characteristics of all the trials were collected and used in the next step.

III. FEATURE SELECTION

A total of 48 gait features were extracted from each subject. This number accounts for different gait characteristics derived from the computerized walkway during the three trials. To consider change in the gait performance by adding a cognitive load in trial 2 and increasing the cognitive load in trial 3, we calculated the change in the gait features from trial 1 to 2, trial 1 to 3, and trial 2 to 3. These new difference-features were added to the features from trials 1-3 resulting in a total of 76 gait features for an individual. Next, we selected the significant features. This was performed by selecting the gait features with p-value<0.05 when an unpaired t-test was used between the HC and MCI groups. A total of 27 significant features were selected out of which 3 were from the difference-features, 4 from trial 1, 11 from trial 2, and 9 from trial 3. After feature selection, each feature value was normalized to x′ using the formula:

| (1) |

where x is the original feature value, is the mean of the feature value for all subjects in the training set (explained in Section IV), and σ is the standard deviation.

IV. BUILDING HC vs. MCI CLASSIFICATION MODEL

A. Support Vector Machine

SVM is a binary classification method useful for datasets involving many features. First, we selected 80% of the subjects for training the model and the remaining were left as the held-out test data. We employed a five-fold cross validation to select the model hyper-parameters. For this purpose, the training data were divided into five folds. Four of them were used to train an SVM with different parameters (cost, gamma, and kernel function), and the remaining fold was used for validating each sets of parameters. The gird search for the gamma and cost values was in the range of 2−10 to 210. The values of the kernel functions were linear, radial basis function, and polynomial. This process was repeated five times for different folds, and the parameter set with the highest validation accuracy was selected for training the SVM classifier. To evaluate the trained SVM model, the trained classifier was applied on the held-out test data.

B. Gradient Tree Boosting

Gradient boosting is used for regression and classification problems and provides a prediction model in the form of an ensemble of several weak decision trees. We trained a gradient tree boosting in the same way as the SM method. The only difference is that we did not employ a feature selection method to choose the significant features before developing a classification model. The reason is that decision trees tend to select the important features, so selecting the features before hand defeats the purpose behind decision trees. Instead, we used the entire features as the input to the model.

V. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The computerized-walkway data from the dual-task assessment of 92 healthy control and MCI subjects were used in this study. A total of 27 feature values were extracted and selected form each subject. An SVM and gradient tree boosting classifier was trained and tested using 5-fold cross-validation. The model based on gradient tree boosting resulted in an only 72% accuracy while SVM resulted in 77.17% accuracy. Hence, we continued our analysis using the SVM model. The SVM testing classification results are shown in Table III. The method resulted in 77.17% accuracy with 81.97% sensitivity and 67.74% specificity.

TABLE III.

Classification Results for HC vs. MCI Using Dual-task assessment + SVM

| Detected | ||

|---|---|---|

| MCI | HC | |

| MCI | 50 | 11 |

| HC | 10 | 21 |

| (H: 2, SCD: 8) | (H: 14, SCD: 7) | |

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| 77.17% | 81.97% | 67.74% |

For comparison purposes, we used MoCA score to detect MCI subjects. Clinical studies have show that a MoCA cut-off of 24 is appropriate for screening MCI subjects [11]. We applied this criteria to our dataset and classified any subject with MoCA <24 as MCI and the rest as HC. This method resulted in a classification accuracy of 76.09%, sensitivity of 70.49%, and specificity of 87.10% as shown in Table IV.

TABLE IV.

Classification Results for HC vs. MCI Using MoCA Score

| Detected | ||

|---|---|---|

| MCI | HC | |

| MCI | 43 | 18 |

| HC | 5 | 26 |

| (H: 0, SCD: 5) | (H: 16, SCD: 10) | |

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| 76.09% | 70.49% | 87.10% |

Comparing the result from the MoCA scores with the SVM + dual-task assessment, we observe that our approach provides a high sensitivity in detecting MCI subjects. It seems that MoCA detects more of the HC subjects correctly. However, our further analysis that 80% of the HC subjects who are miss-classified as MCI using our method are actually SCD subjects. One explanation could be that these SCD subjects have developed into early-stage MCI, but the standard-of-care using MoCA score yet to detect the signs. This is while the machine learning approach enables to detect early-sign patterns in these SCD subjects.

Moreover, we used a MoCA cut-off of 24 in our analysis instead of determining the optimal cut-off value using the receiver operating curve method. The reason is to be consistent with the clinically defined cut-off that has been set based on the analysis of a large population rather than defining a new threshold for our population.

Another interesting observation from our studies is the number of significant gait features from different trials with different cognitive loads. Our analysis indicates that four of the baseline gait features in trial 1 provide some indication of early cognitive decline. However, this number increases to 11 and 9 in trials 2 and 3, respectively. This observation supports that the individuals with cognitive decline demonstrate a larger decrease in their functional performance (i.e., gait in this study). Our future work will investigate the extraction of these significant gait features from other data acquisition systems such as wearable, which are portable and can be utilized outside of clinical settings.

VI. CONCLUSION

In this study, we collected dual-task and cognitive assessment data of 92 HC and MCI subjects. We used MoCA, which is a commonly-used cognitive assessment test. For the dual-task assessments, we used Zenomat to collect gait data. We used a machine learning approach to identify subjects with MCI from HC using gait data obtained from dual-task assessment. Unlike the existing approaches, which mainly investigate a significant association of single gait features with cognitive decline, we used machine learning to investigate the collective application of the gait features in detecting MCI vs. HC subjects. We used two machine learning models: SVM and gradient tree boosting, where the former showed a promising performance with 81.52% accuracy, 86.89% sensitivity, and 46.88% specificity. This is while the commonly-used paper-based method known as MoCA score provided only an accuracy of 76.09% with 70.49% sensitivity and 87.10% specificity on our dataset. In addition, our SVM + dual-task approach suggested that MoCA score might falsely detect SCD subjects who are at early stages of developing MCI as HC. However, more investigations are required. Our future work consists of creating a larger dataset and improving our analysis approach by extracting additional gait features form the raw dual-task gait signals.

Fig. 1.

The Zenomat walkway system was used by patients for the gait assessment trials. The data collected by its pressure sensors was used to calculate components of gait for both the left and right sides of patients. The data was limited through feature selection and normalized. Then the selected data was put through an SVM training model for the results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program at Florida Department of Health AWD-001693.

References

- [1].König A, Klaming L, Pijl M, Demeurraux A, David R, and Robert P, “Objective Measurement of Gait Parameters in Healthy and Cognitively Impaired Elderly Using the Dual-Task Paradigm,” Springerlink, January. 2017, pp. 1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Akushevich I, Yashkin A, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Stallard E and Yashin A, “Time Trends in the Prevalence of Neurocognitive Disorders and Cognitive Impairment in the United States: The Effects of Disease Severity and Improved Ascertainment,” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, pp. 1–12, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hughes C, Berg L, Danziger W, Coben L and Martin R, “A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 140, no. 6, pp. 566–572, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Belghali M, Chastan N, Cignetti F, Davenne D and Decker L, “Loss of gait control assessed by cognitive-motor dual-tasks: pros and cons in detecting people at risk of developing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases,” GeroScience, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 305–329, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Morris R, Lord S, Bunce J, Burn D and Rochester L, “Gait and cognition: mapping the global and discrete relationships in ageing and neurodegenerative disease,” Neuroscience Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 64, pp. 326–345, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Verghese J, Robbins M, Holtzer R, Zimmerman M, Wang C, Xue X and Lipton R, “Gait dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment syndromes,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 56, no. 7, pp. 1244–1251, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Scherder E, Eggermont L, Swaab D, van Heuvelen M, Kamsma Y, de Greef M, et al. , “Gait in ageing and associated dementias; its relationship with cognition,” Neurosci Biobehav Rev, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 485–497, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Beauchet O, “Gait analysis in demented subjects: interests and perspectives,” Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment, vol. 4, no. 1A, p. 155, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beauchet O, Allali G, Thiery S, Gautier J, Fantino B, Annweiler C, “Association between high variability of gait speed and mild cognitive impairment: a cross-sectional pilot study,” J Am Geriatr Soc, vol. 59, no. 10, pp. 1973–1974, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alberdi A, Aztiria A and Basarab A, “On the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease from multimodal signals: A survey,” Artificial intelligence in medicine, vol. 71, pp.1–29, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].O’Caoimh R, Timmons S and Molloy DW, “Screening for mild cognitive impairment: comparison of “MCI specific” screening instruments,” Journal of Alzheimer’s disease, vol. 51, no. 2, pp.619–629, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]