Abstract

Background:

The American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS) Maintenance of Certification® (MOC) program includes the submission of 10 consecutive cases in one of 20 tracer modules for Performance in Practice evaluation. This has resulted in a wealth of data on the practice patterns of ABPS diplomates. The specific aim of this project is to examine these data to determine whether diplomates are adhering to evidence-based practice guidelines.

Methods:

We searched the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National Guideline Clearinghouse for guidelines. Once identified, we compared the recommendations to data entered by ABPS diplomates for the tracer modules in question. It is important to note that guidelines are recommendations based on the best available evidence and that all guidelines are subject to change, pending periodic reexamination of the evidence.

Results:

Diplomates are adhering to guidelines regarding age of cosmetic breast augmentation patients, use of prophylactic antibiotics and DVT prophylaxis in abdominoplasty patients and use of carpal tunnel release in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. However, half of diplomates are using splints following carpal tunnel release, despite recommendations to the contrary. Additionally, only half of diplomats are following guidelines recommending mammography prior to breast augmentation. Furthermore, 90% of diplomates are not following recommendations against the use of DVT prophylaxis for patients with acute lower limb trauma.

Conclusions:

This study revealed that there were few guidelines with which to compare diplomate performance. Steps should be taken to increase the number of evidence-based practice guidelines for plastic surgery procedures.

Keywords: Practice guidelines, Maintenance of Certification, American Board of Plastic Surgery

In 2000, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) made official the ABMS Maintenance of Certification® (MOC) program, and all 24 ABMS member boards have approved this program by 2006. For physicians who were awarded time-limited board certification (beginning in 1995 for Plastic Surgery), every 10 years the MOC process requires proof of continuing education and practice assessment experience, along with computer-based examination.(1) MOC ensures that physicians are “committed to lifelong learning and competency in a specialty or subspecialty by requiring ongoing measurement of six core competencies.”(2) The six core competencies are: patient care, medical knowledge, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, systems-based practice and practice-based learning.(2) The goal is to improve the overall care and safety of patients by ensuring that physicians keep up with advances in research and technology.(2) As the role of evidence-based medicine increases,(3, 4) MOC is a call to ensure that physicians practice medicine using published guidelines to improve patient care.(5)

The American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS), in conjunction with the ABMS, developed the MOC in Plastic Surgery program (MOC-PS) with four components (professionalism, lifelong learning and self-assessment in plastic surgery, testing of knowledge and evaluation of performance in practice).(6) Although all 4 parts of MOC are essential, it is the performance in practice component that is most important for surgeons.(7) This component appraises the performance, patient care and outcomes of ABPS diplomates to assure competent practice of Plastic Surgery. This process involves a “measure-change-remeasure model,” whereby diplomates can assess the quality of care they provide by comparing their performance in submitted case-logs with benchmarks, to apply the best evidence to improve that care. Follow-up assessments of the practices of plastic surgeons help to assure improved performance.(8)

The result of this process is the collection of a substantial amount of data on the practice patterns of ABPS diplomates. Although MOC data have been suggested as a tool to examine treatment trends and clinical experience,(9, 10) no ABMS boards have yet published analyses of this data. The specific aim of this project is to present data from the Practice Assessment in Plastic Surgery (PA-PS) module of the MOC-PS process to evaluate whether ABPS diplomates are practicing evidence-based medicine by adhering to recommendations from accepted practice guidelines.

Methods

The Practice Assessment in Plastic Surgery Module must be completed three, six and nine years following initial certification and is repeated for each 10 year cycle. Diplomates must select one of the 20 tracer procedures available (Table 1) and enter, via a secure online system, 10 consecutive cases completed in the preceding 3 years.(11) For each tracer, the diplomate must enter data about the patient, the procedure and the outcomes of each case. The questions are specific to each tracer; there is an average of 44 questions for each tracer (range: 30–99). Seven questions are asked in all 20 tracers: procedure year, procedure location, procedure CPT code(s), patient age, adverse events, physician satisfaction and surgical treatment plan. The remaining, tracer-specific questions are created by the Directors and Advisory Counsel Members of ABPS, using each Director or Member’s individual areas of expertise.

Table 1.

The 20 Tracer procedures monitored by the American Board of Plastic Surgery(2)

| Comprehensive | Cosmetic | Craniomaxillofacial | Hand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Reconstruction | Abdominoplasty | Cleft Palate | Carpal Tunnel Syndrome |

| Facial Skin Malignancy | Augmentation Mammaplasty | Genioplasty | Dupuytren’s Disease |

| Lower Extremity Acute Trauma | Blepharoplasty | Non-syndromic Craniosynostosis | Flexor Tendon Laceration |

| Pressure Sores | Face Lift | Secondary Cleft Nasal Deformity | Metacarpal fracture |

| Reduction Mammaplasty | Suction Assisted Lipectomy | Zygomatic Fracture | Thumb Carpometacarpal Arthritis |

Descriptive Statistics

The first portion of our data analysis involved examining descriptive statistics for the top five selected tracer procedures. (Table 2) For each of the top five procedures, we obtained mean patient age, patient gender, surgery location, physician satisfaction and physician-perceived patient satisfaction. We also examined a variety of procedure-specific variables.

Table 2.

Number of diplomates selecting each Tracer procedure, 2008–2009

| Tracer | Number of diplomates selecting |

|---|---|

| Augmentation Mammaplasty | 435 |

| Reduction Mammaplasty | 351 |

| Breast Reconstruction | 135 |

| Abdominoplasty | 124 |

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | 115 |

| Facial Skin Malignancy | 64 |

| Cleft Palate | 46 |

| Blepharoplasty | 40 |

| Face Lift | 29 |

| Suction Assisted Lipectomy | 26 |

| Lower Extremity Trauma | 13 |

| Flexor Tendon Laceration | 12 |

| Metacarpal Fracture | 9 |

| Pressure Sore | 9 |

| Non-syndromic Craniosynostosis | 7 |

| Thumb Carpometacarpal Arthritis | 6 |

| Zygomatic Fracture | 6 |

| Dupuytren’s Disease | 2 |

| Secondary Cleft Nasal Deformity | 1 |

| Genioplasty | 0 |

Adherence to Practice Guidelines

We searched the National Guideline Clearinghouse maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality related to any of the 20 tracer procedures.(12) To be included in the clearinghouse, guidelines must be systematically developed and evidence-based.(13) We also searched for practice parameters and policy statements on the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) website and on the websites of other professional organizations relevant to the tracer procedures. When we identified a relevant guideline or policy, we examined the text for statements that could be tested using the variables collected by ABPS. We then referred to the dataset to assess compliance with this guideline or policy. It is important to note that guidelines are recommendations based on the best available evidence and that all guidelines are subject to change, pending periodic reexamination of the evidence. This project was approved by the Data Committee of the American Board of Plastic Surgery. Permission to analyze and publish this proprietary data was also granted by all the directors of American Board of Plastic Surgery.

Results

Two years of entered data, from 2008 and 2009, were analyzed. Because diplomates are allowed to report any 10 consecutive cases from the previous 3 years, surgery dates for the analyzed data ranged from 2005 to 2009.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 shows the results for common variables collected from each of the top five tracer modules, and data for each of these five tracer modules will be presented sequentially.

Table 3.

Variables common to the top 5 Tracer procedures

| Number of Cases | Mean patient age (range) | Physician Satisfactiona (%Satisfied) | Physician-perceived Patient Satisfactionb (%Satisfied) | Adverse Eventsc (% selecting at least one from list) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augmentation Mammaplasty | 4350 | 33.0 (17–79) | 95.8% | 93.6% | 10.7% |

| Reduction Mammaplasty | 3510 | 39.4 (13–82) | 97.7% | 98.6% | 30.1% |

| Breast Reconstruction | 1350 | 49.9 (14–80) | 76.4% | 97.7% | 28.7% |

| Abdominoplasty | 1240 | 41.2 (16–71) | 98.0% | 98.4% | 23.2% |

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | 1150 | 55.2 (6–89) | 97.4% | 96.7% | 10.1% |

“Physician Satisfaction with End Result: □Satisfied □Dissatisfied □N/A”

“Patient Satisfaction with End Result: □Satisfied □Dissatisfied □N/A”

“Post-operative Adverse Events: (select from Tracer specific list of possible adverse events)”

Augmentation Mammaplasty

In 4350 cases in this module, reported from 2008 and 2009, over 75% of patients had a pre-operative cup size of A or B (40.0% and 38.6%, respectively). Only 4.4% had a pre-operative cup size smaller than A and 13.3% had a pre-operative cup size of C or larger; 2.7% of cases had no reported pre-operative cup size. Post-operatively, 46.5% of patients had a C cup size, whereas 35.8% had a D cup size or larger. Only 7% had a post-operative cup size of B or smaller; 11% of cases had no reported post-operative cup size.

Generally, physicians felt that their patients were satisfied with the outcome of their breast augmentation. The primary reasons physicians thought that patients were dissatisfied were breasts that were too small (78% of cases with reported patient dissatisfaction) or too large (10%) or implant malposition (12%). Implant type was split with approximately half of cases using saline implants (51.4%) and the other half being a form of silicone gel (48.2%).; 0.4% of cases did not have an implant type reported.

43.5% of procedures were performed in a freestanding surgery facility and 32.7% in an office operating room; 21.2% of procedures were performed as an outpatient procedure in a hospital, whereas only 2.0% were performed as an inpatient procedure; 0.6% of cases did not report a surgery location. Complication rates for this procedure are pending.

Reduction Mammaplasty

In 2008 and 2009, 3510 cases were reported in this module. Pre-operatively, 13.1% of patients had a pre-operative cup size of D or smaller, 41.1% of patient had a cup size of DD, 23.8% had a cup size of DDD and 20.6% had a cup size larger than DDD; 1.4% of cases had no reported pre-operative cup size. Nearly 80% of procedures were performed in a hospital: 55.8% as an outpatient and 22.7% as an inpatient; 18.4% of procedures were performed in a freestanding surgery facility, whereas only 3.1% were performed in an office operating room. For the 74.4% of patient who were working at the time of their surgery, the average length of time until return to work was 2.6 weeks (range: 0–30 weeks).

Adverse events were reported in 30.1% of the patients. Most common were delayed healing (experienced by 6.5% of all reported reduction mammaplasty cases), hypertrophic or keloid scar (2.6%), wound dehiscence (2.3%), fat necrosis (1.3%) and wound infection (1.3%); 1.7% of patients experiencing adverse events were hospitalized due to these complications.

Breast Reconstruction

For this module, 1350 cases were reported. Immediate reconstruction was in 72.7% of cases. In 11.8% of cases, the reconstruction took place within 1 year. Reconstruction took place between 2 and 10 years in 12.3% of cases. Reconstruction took place after 10 years in only 1.2% of cases; 2% of cases did not report a reconstruction time. Autologous tissue was used in 39.3% of cases and not use in 31.9% of cases; 28.8% of cases did not report data on use of autologous tissue. The specific breast reconstruction technique used was not reported in 56.8% of cases, making data regarding technique reported by other diplomate unreliable.

The majority of cases were performed in a hospital, 68.8% as an inpatient and 25.7% as an outpatient; 4.7% of cases took place in a freestanding surgery facility. Only 0.22% of cases were performed in an office operating room. 0.58% of cases did not have a surgery location reported. The average length of hospital stay was 2.1 days (range: 0–18 days). For the 71.3% of patients who were working at the time of their surgery, the average length of time off work was 4.3 weeks (range: 0–60 weeks).

28.7% of patients experienced adverse events. Most common were seroma (experienced by 5.5% of all reported breast reconstruction cases), infection requiring oral antibiotics (5.0%), chest wall skin loss (4.8%), fat necrosis (4.4%) and hematoma (3.5%).

Abdominoplasty

In 2008 and 2009, 1240 cases were reported in this module. The majority of patients were female (96.5%). Surgery location was split fairly equally among the four locations: 34.4% of procedures were performed at freestanding surgery facilities, 27.9% as inpatient hospital procedures, 22.4% in office operating rooms and 15.3% as outpatient procedures.

Adverse events were reported in 23.2% of patients. Most common were seroma (experienced by 7.3% of all reported abdominoplasty cases), infection requiring oral antibiotics (2.3%) and prolonged edema (1.9%).

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

1150 cases were reported for this module during 2008 and 2009. Approximately two-thirds of patients were female (63.2%). A little more than 60% of procedures were performed as outpatient procedures: 34.9% at freestanding surgery facilities and 58.3% as outpatient procedures in a hospital. An additional 4.4% of procedures were performed in office operating rooms. Only 1.6% of cases were performed as an inpatient procedure. 0.8% of cases did not have a reported surgery location.

Adverse events were reported in 10.1% of patients. Most common were persistent pain (experienced by 2.3% of all reported patients with carpal tunnel syndrome) and persistent numbness (1.7%).

Practice Guidelines

Breast Augmentation

In 2004, the ASPS issued a policy statement on the performance of purely aesthetic breast augmentation on teenagers.(14) The official position of ASPS is that breast augmentation, unless done for reconstructive reasons, should be performed only on patients over the age of 18. Reasons for this position include the possibilities that teenage patients may not fully appreciate the risks involved in elective surgery, along with the potential for further breast development as patients reach physical maturity.

Diplomates reported that all but 5 patients (99.9%) were age 18 or over at the time of breast augmentation surgery, indicating that almost all diplomates are complying with this policy statement.

Because the changes caused by cosmetic breast surgery can make mammography difficult to interpret, preoperative breast cancer screening is an important part of the preoperative examination.(15) The American Cancer Society calls for annual mammography for all women with age 40 and over. For women with a family history or other increased risks, annual screening can begin for women as young as 20-years of age.(16)

Diplomates reported ordering mammography for 51.5% of women age 40 or over who did not have a prior mammogram; 39.5% of women under 40 with a family history of breast cancer, also without prior mammogram, were referred for mammography.

Abdominoplasty

ASPS issued a practice parameter regarding the indications for and performance of abdominoplasty in 2006.(17) This practice parameter encourages the use of prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis (DVT), as well as the use of prophylactic antibiotics. According to the MOC dataset, diplomates are complying with both of these suggestions: DVT prophylaxis was used in 99.8% of abdominoplasty cases, and prophylactic antibiotics were used in 98.5% of cases.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

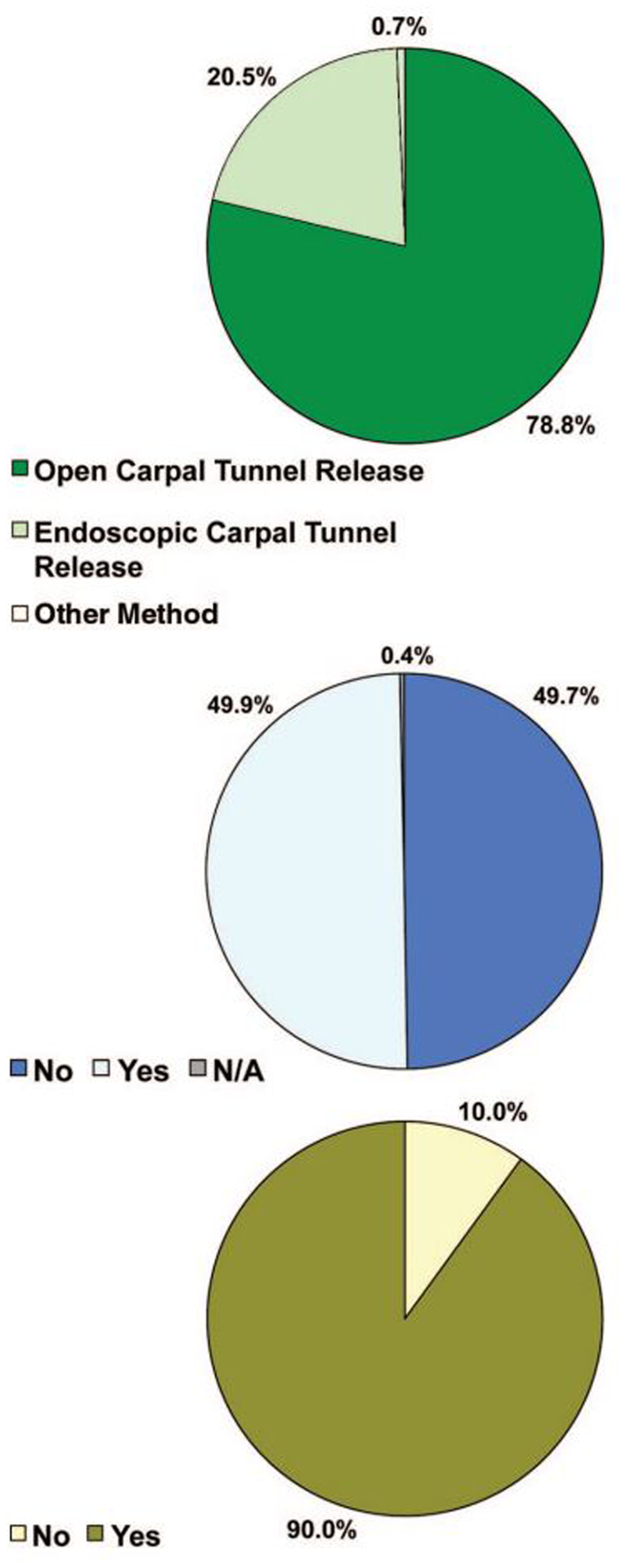

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) issued a clinical practice guideline on the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome in 2008.(18) AAOS levied a Grade A recommendation (indicating strong evidence in support of the recommended course of action(19)) in favor of carpal tunnel release as the preferred treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. This recommendation comes following multiple studies showing carpal tunnel release’s effectiveness versus non-operative treatment.(18) We examined the CPT codes reported by diplomates completing the carpal tunnel syndrome Tracer module and found that 78.8% reported using open carpal tunnel release, 20.5% endoscopic carpal tunnel release and 0.7% did not list an appropriate code for surgical carpal tunnel syndrome treatment.. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Procedure used for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome

Footnote: Carpal Tunnel Release: CPT code 64721; Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release: CPT code 29848

AAOS gave a Grade B (indicating fair evidence in support of the suggested course of action(19)) to the suggestion that the wrist not be immobilized following routine carpal tunnel surgery. This suggestion was made with evidence showing no increase in pinch strength, patient-rated outcomes or patient satisfaction following splinting.(18) Additionally, splinting did not have an effect on complication rates. Despite this suggestion, an examination of cases performed by diplomates indicated that between 2005 and 2009, 49.9% of diplomates were still splinting patients following carpal tunnel surgery. (Figure 2)

Lower Extremity Acute Trauma

In 2008, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) issued evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on the prevention of DVT for a variety of surgical procedures. They issued a Grade A guideline recommending that DVT prophylaxis not be used during surgical treatment of isolated lower-extremity trauma.(20) ACCP found that there is little evidence to show that prophylaxis appreciably reduces the risk of DVT in these patients.(20) Despite these recommendations, diplomates reported using DVT prophylaxis during 90% of cases treating acute lower-extremity trauma between 2005 and 2009. (Figure 3)

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that ABPS diplomates were adhering to published practice guidelines, parameters and policies for age at breast augmentation and use of prophylactic antibiotics and DVT prevention in abdominoplasty. Additionally, diplomates perform the currently accepted surgical techniques to treat carpal tunnel syndrome. However, there is a discrepancy between what practice guidelines are recommending and what diplomates reported for splinting following carpal tunnel surgery and DVT prevention for patients with lower-extremity trauma. For carpal tunnel syndrome, practice guidelines recommend that the wrist not be immobilized after surgery. This recommendation was not followed by half of the ABPS diplomates. For lower-extremity trauma, guidelines recommend not using DVT prophylaxis during surgery. This guideline was not followed by 90% of ABPS diplomates.

We performed a literature search to examine plastic surgeons’ adherence to other practice guidelines and found only one study, a survey of ASPS members’ adherence to American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening prior to cosmetic breast surgery. Selber et al. found that 89.1% of respondents reported obtaining mammography based on age and 57.1% based on family history.(15) This is in contrast to our data in which diplomates reported ordering mammography for 51.5% of women age 40 or over who did not have a history of prior mammogram and 39.5% of women under 40 with a family history of breast cancer, also without prior mammogram, were also referred for mammography. This is especially interesting, given that the population of ASPS members and ABPS diplomates may overlap. Data collection methods may play a role in this discrepancy. ASPS members were asked recall questions about their practice in general, whereas ABPS diplomates were entering data based on case review, presumably while consulting the case chart.

There were no other published studies of adherence, by plastic surgeons or other specialties, for the specific procedures and guidelines we examine in this manuscript. Thus, we were not able to compare guideline adherence further. It is not valid to compare adherence rates to different guidelines because factors such as patient compliance, guidelines dissemination and complexity of the medical condition or treatment in question play a large role in adherence.(21) In the future, it would be beneficial to compare different specialties’ adherence to the same guideline.

The nonadherence to guidelines in the selected modules may not be deleterious to the care that patients received. The AAOS’s guideline regarding splinting was issued a Grade B, meaning it is merely a suggestion.(19) Although the ACCP issued a Grade A to their recommendation against the use of DVT prophylaxis during surgery for acute lower limb trauma, the guideline states that pending further research, surgeons are free to provide, or not provide, DVT prophylaxis as they wish. Neither splinting nor the use of DVT prophylaxis has severe health consequences if prescribed. But the use of unnecessary treatments is costly. With limited healthcare resources available, it should be the goal of every diplomate to provide the best possible patient care at the lowest possible cost.

This paper illustrates the paucity of evidence-based practice guidelines for plastic surgery procedures. Although there is uncertainty about exactly how healthcare reform in the US will reshape the delivery of care, there is little question that the role of evidence-based medicine is going to grow. (3, 4) Carefully constructed practice guidelines can assist ABPS diplomates in practicing evidence-medicine, which will be the core stipulation of future healthcare movements. The performance of physicians and the credibility of a specialty to the public will be judged by their engagement in evidence-based medicine.

This analysis is not without limitations. Primarily, there were few practice guidelines available for comparison. Only three rigorous evidence-based, graded clinical practice guidelines existed for the 20 procedures. It is impossible to determine compliance if adequate guidelines do not exist. Secondly, the MOC data were not collected for data analysis purposes. Although ASPS produced graded recommendations for the practice of liposuction procedures,(22) the MOC data collected did not align with the topics covered in the practice guideline recommendations and we were unable to assess performance for this tracer. The number of questions and level of detail varied greatly amongst the tracer modules. Some tracers had nearly 3 times as many questions as or than others. Increasing consistency of questions between tracers, where possible, will facilitate future data analysis.

Despite these limitations, our analysis is the first of its kind. Other investigations of practice guideline compliance have used chart review or physician-administered surveys. This paper presented the first application of data collected during the MOC process to evaluate current diplomate practice. Although, initially, there was resistance to participation in the MOC process,(5) this analysis shows that in addition to serving an important role in fostering trust among patients and the general public, the MOC process can provide a wealth of data to improve quality of care. The effort of the ABPS in the MOC process has demonstrated that ABPS diplomates are engaged in evidence-based medicine. In addition, the MOC process shows the public that plastic surgeons are keen to provide quality care to the patients they serve.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sandra Kotsis, MPH; Terry Cullison, R.N., MSN and John J. Harrast for their help in the development and writing of this manuscript. Supported in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

References

- 1.American Board of Medical Specialties. What board certification means. http://www.abms.org/about_board_certification/means.aspx. Accessed on February 23, 2010.

- 2.American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Maintenance of Certification.

- 3.Chung KC, Ram AN Evidence-based medicine: the fourth revolution in American medicine? Plast Reconstr Surg 123: 389–398, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung KC, Swanson JA, Schmitz D, et al. Introducing evidence-based medicine to plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 123: 1385–1389, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung KC, Clapham P, Lalonde DH Maintenance of certification, maintenance of public trust. Plast Reconstr Surg, in submission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohrich RJ, Stuzin JM, Lalonde DH Maintenance of Certification in plastic surgery and the Journal: what you need to know. Plast Reconstr Surg 121: 329–332, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buyske J For the protection of the public and the good of the specialty: maintenance of certification. Arch Surg 144: 101–103, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLisa JA Maintenance of certification: continuing assessment of physician quality with respect to their commitment to quality patient care, lifelong learning, ongoing self-assessment, and improvement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 88: 775–779, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandrick K A new tool for professional development: the ACS Case Log System. Bull Am Coll Surg 91: 13–17, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shabot MM, Tanzman H The ACS Case Log System: a key tool for surgical self-evaluation, privileging, and maintenance of certification. Bull Am Coll Surg 92: 17–20, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Maintenance of certification in plastic surgery booklet of information. Philadelphia: American Board of Plastic Surgery, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Guideline Clearinghouse. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Guideline Clearinghouse. Inclusion Criteria. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Policy statement: breast augmentation in teenagers. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selber JC, Nelson JA, Ashana AO, et al. Breast cancer screening prior to cosmetic breast surgery: ASPS members’ Adherence to American Cancer Society Guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg 124: 1375–1385, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin 53: 141–169, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Practice parameter for abdominoplasty and panniculectomy unrelated to obesity or massive weight loss. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Board of Directors. 2008. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Clinical Practice Guideline on the Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. http://www.aaos.org/Research/guidelines/CTSTreatmentGuideline.pdf Accessed on November 7, 2008.

- 19.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Scale for rating levels of evidence and grading practice recommendations. Arlington Heights, IL: American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 133: 381S–453S, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 282: 1458–1465, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haeck PC, Swanson JA, Gutowski KA, et al. Evidence-based patient safety advisory: liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg 124: 28S–44S, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]