Summary

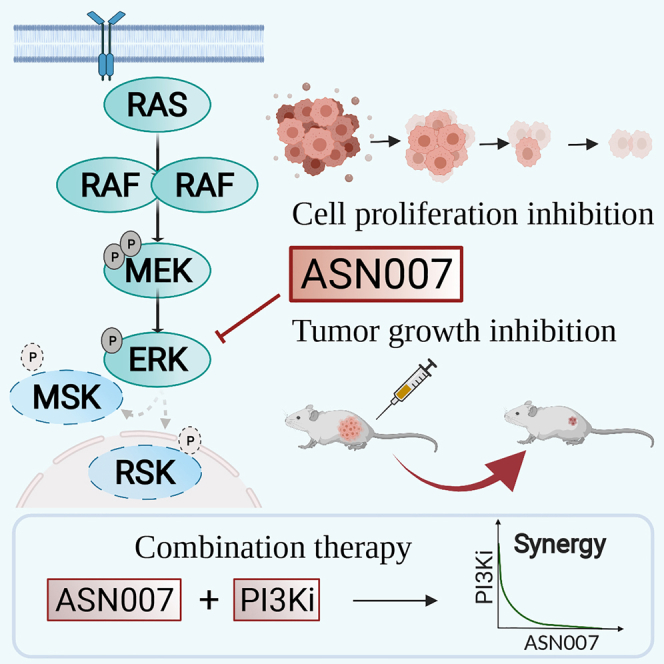

Inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases ERK1 and ERK2 (ERK1/2) offers a promising therapeutic strategy in cancers harboring activated RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Here, we describe an orally bioavailable and selective ERK1/2 inhibitor, ASN007, currently in clinical development for the treatment of cancer. In preclinical studies, ASN007 shows strong antiproliferative activity in tumors harboring mutations in BRAF and RAS (KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS). ASN007 demonstrates activity in a BRAFV600E mutant melanoma tumor model that is resistant to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. The PI3K inhibitor copanlisib enhances the antiproliferative activity of ASN007 both in vitro and in vivo due to dual inhibition of RAS/MAPK and PI3K survival pathways. Our data provide a rationale for evaluating ASN007 in RAS/RAF-driven tumors as well as a mechanistic basis for combining ASN007 with PI3K inhibitors.

Keywords: ERK, kinase inhibitor, ASN007, RAF/RAS-driven cancers, combinational therapy, KRAS, PI3K, biomarker, lymphoma, solid tumors

Graphical abstract

Highlights

ASN007 is a reversible ATP-competitive inhibitor of ERK1 and ERK2 kinase activity

The presence of RAS/RAF pathway mutations predicts enhanced efficacy of ASN007

ASN007 demonstrates strong efficacy in a resistant melanoma PDX model

Combination with a PI3K inhibitor enhances ASN007 antitumor activity in several tumors

Portelinha et al. describe a selective ERK1/2 kinase inhibitor, ASN007, with antitumor activity against several solid tumors and lymphomas. Moreover, the authors show that PI3K inhibition enhances the activity of ASN007.

Introduction

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, also known as the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway, regulates a variety of physiologic cell functions, including cell proliferation and survival.1,2 RAS activation by upstream receptors requires a switch from the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound to the guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound form. This conformational change leads to RAF binding, promoting its dimerization and activation.3 Activated RAF phosphorylates and activates mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) which phosphorylates and activates ERK1/2 at threonine and tyrosine sites. ERK regulates a variety of cell functions by phosphorylating >200 cytoplasmic and nuclear substrates.4,5

This physiologic pathway is frequently hijacked by cancer cells, through activating mutations in RAS and RAF genes.1,2,6 From a therapeutic point of view, this activated pathway can be targeted at different node levels. To date, only drugs targeting BRAF (vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib) or MEK (trametinib, binimetinib, and cobimetinib) have been approved by regulatory agencies for the treatment of BRAFV600E mutant melanoma.4,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Newer strategies are exploring targeting the most proximal node, RAS, or the most distal node, ERK1/2. Several ERK1/2 inhibitors are in development, including ulixertinib (BVD-523), ravoxertinib (GDC-0994), and SCH772984.14, 15, 16 Rationale for these strategies is aimed at improving the quality and duration of clinical responses achieved by RAF and MEK inhibitors, to overcome acquired resistance, which may include activation of ERK1/2 through a feedback mechanism, and to broaden tumor types that may benefit from inhibiting this pathway.4,14,17,18

In this study, we describe a potent and selective ERK1/2 inhibitor, ASN007, which is in clinical development for the treatment of cancer. We show that ASN007 has broad antiproliferative activity in both solid tumors and lymphoma, with preferential sensitivity in RAS and BRAF mutant cancers. We also describe enhanced antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo using a combinational treatment of ASN007 and a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor.

Results

Discovery and biochemical characterization of the selective ERK1/2 inhibitor ASN007

The imidazole carboxamide scaffold was used as a starting point to discover and develop potent and selective inhibitors of ERK1 and ERK2 kinases. A structure-activity-based approach was used to systematically modify the key moieties of the compounds to optimize the pharmacological features, comprising synthesis and testing of >600 compounds. The evaluation of multiple parameters such as potency and selectivity for ERK kinase inhibition, cell-based mechanistic and antiproliferative activity, pharmacokinetics, and in vivo efficacy led to the identification of ASN007, N-(2-amino-1-(3-chloro-5-fluorophenyl)ethyl)-1-(5-methyl-2-((tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)-1H-imidazole-4-carboxamide (Figure 1A) as a promising lead compound for further development. In cell-free biochemical assays, ASN007 inhibited ERK1 and ERK2 with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 2 nM against both kinases (Figure 1B). In comparison, SCH772984 showed IC50 values of 8 and 3 nM against ERK1 and ERK2, respectively.

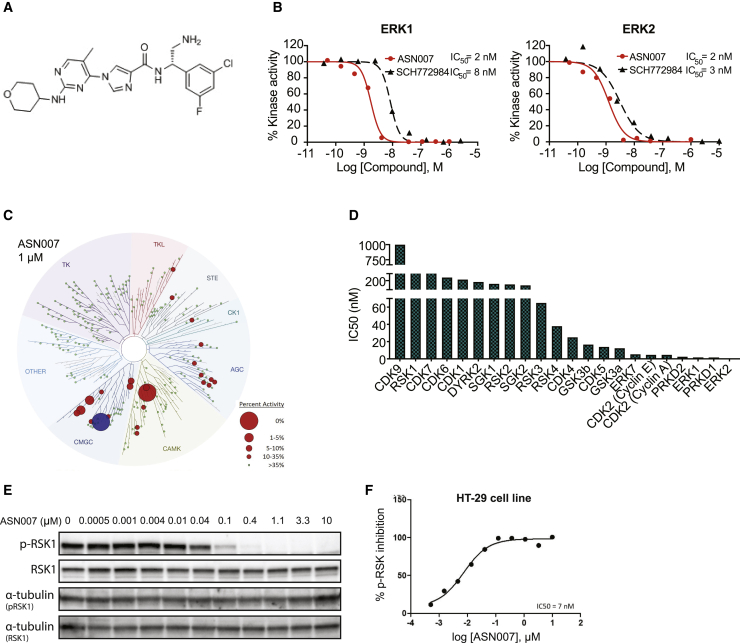

Figure 1.

Structural and biochemical characterization of ASN007

(A) Molecular structure of ASN007, MW = 473.

(B) Dose-response curves of ERK1/2 inhibitors (ASN007 or SCH772894) in a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF)-based ERK1/2 enzymatic activity assay.

(C) Kinome tree dendrogram showing the biochemical kinase profiling assay (KinaseProfiler, Eurofiler), which measures the kinase inhibitory activity of ASN007 in a radiometric enzymatic assay in a panel of 335 purified kinases. Hit kinases reported are marked with a red circle and the size of the circle indicates the relative potency of ASN007 for each kinase. ERK1/2 kinases are illustrated by a blue circle. Green dots indicate kinases against which ASN007 does not have significant activity at 1 μM. The dendrogram was generated using the web tool TREESpot, provided by DiscoverX.

(D) IC50 values (nM) for ASN007 against the top 22 kinases, which showed >75% inhibition at 1 μμM, identified from the primary kinome screening.

(E) Dose-dependent effect of ASN007 treatment on phosphorylation of ERK1/2 targets. Representative western blot analysis shows inhibition of RSK1 (Ser380) phosphorylation after 4h of ASN007 treatment in a colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line, HT-29.

(F) Dose-response curve of ASN007 inhibition of RSK phosphorylation in the human colon cancer HT-29 BRAFV600E mutant cell line, measured by an ELISA test.

In a primary kinome screening assay comprising a panel of 335 serine/threonine, tyrosine, and protein lipid kinases, ASN007 demonstrated a selective inhibition of ERK1/2 kinases at 1.0 μM concentration (Figure 1C; Table S1). IC50 determination for the top 22 kinases, which showed >75% inhibition at 1 μM, confirmed the selectivity of ASN007 for ERK1 and ERK2, in addition to the inhibition of a small number of kinases belonging to the CMGC and CAMK kinase subfamilies (Figure 1D).

ASN007 treatment promotes the dose-dependent decrease in the phosphorylation level of ERK1/2 protein targets RSK-1 and FRA-1 in HT-29, a colorectal cancer cell line harboring BRAFV600E mutation (data not shown; Figure 1E). The inhibitory effect of ASN007 on RSK-1 phosphorylation was further confirmed in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Figure 1F). The inhibition of ERK1/2 targets MSK1 and RSK1 was observed as early as 15 min with ASN007 treatment and lasted for at least 72 h, as shown by time-dependent analysis in a mantle cell lymphoma (JeKo-1) and a melanoma (A375) cell line (Figure S1A). The antiproliferative activity of ASN007 was mainly due to the induction of a time-dependent cell-cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase (Figure S1B; Table S2).

The potential functional effects of the inhibition of the off-target kinases were investigated in both in vitro cell lines and in vivo tumor xenograft models. ASN007 demonstrated no evidence of the mechanistic inhibition of CDK2, CDK4, GSK3, or PRDK1, confirming its selectivity in cells (Figure S1C) and tumors (Figure S1D).

Preferential activity of ASN007 against RAS/RAF pathway mutant cancers

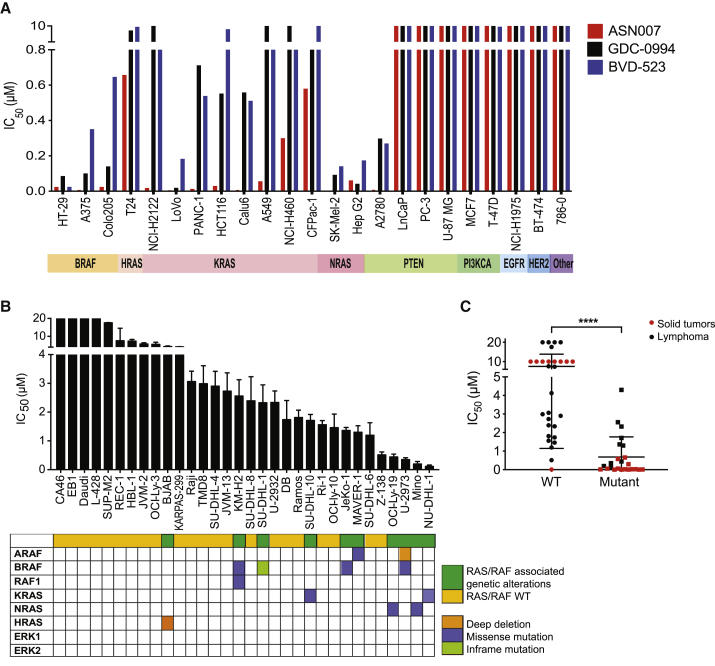

The antiproliferative activity of ASN007 was assessed in a panel of 23 solid tumor cell lines with (n = 14) or without (n = 9) genetic alterations in the RAS/RAF pathway (Figure 2A). Similar to the ERK1/2 inhibitors GDC-0994 and BVD-523, ASN007 showed preferential antiproliferative activity in cell lines harboring mutations in the RAS/RAF pathway, with a median IC50 of 37 nM (range, 13–100 nM), compared to IC50 values of >10,000 nM in cell lines without the mutations (Table 1). However, ASN007 demonstrated greater potency compared to GDC-0994 and BVD-523 in cell lines harboring RAS/RAF mutations (Figure 2A). Similar results were observed in a panel of lymphoma cell lines (n = 32) representing a wide range of histologic subtypes (Figure 2B). The compound was particularly potent against KRASA146T mutant cell line NU-DHL-1, NRASG13D mutant cell line MINO, and BRAFV600E mutant lymphoma cell line U-2973, with IC50 values of 100, 200, and 300 nM, respectively (Table 2). Thus, the presence of RAS/RAF pathway mutations was predictive of the enhanced efficacy of ASN007, irrespective of the tumor type (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Antiproliferative efficacy of ASN007 in solid tumor and lymphoma cell lines

(A) The IC50 values of ASN007 were compared with two other ERK1/2 inhibitors (ulixertinib/BVD-523 and ravoxertinib/GDC-0994) in a panel of solid tumor cell lines with or without mutations in the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of the specified ERK1/2 inhibitor for 72 h before cell viability assessment.

(B) ASN007 was more effective against lymphoma cell lines harboring mutations in the RAS/RAF pathway. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

(C) Dot plot comparing IC50 values of ASN007 in cell lines with or without mutations in the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway. Black dots illustrate IC50 values for lymphoma cell lines and red dots illustrate solid tumor cell lines. Differences between groups were calculated with Student’s t test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Table 1.

IC50 values for representative RAS and RAF mutant cell lines

| Cell line | IC50 (μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Gene mutated | Mutation (RAS pathway) | ASN007 | GDC-0994 | BVD-523 | |

| HT-29 | colon | BRAF | V600E | 0.020 | 0.082 | 0.021 |

| A375 | skin | BRAF | V600E | 0.007 | 0.097 | 0.347 |

| Colo 205 | colon | BRAF | V600E | 0.021 | 0.137 | 0.643 |

| T24 | bladder | HRAS | G12V | 0.653 | 8.335 | 9.512 |

| NCI-H2122 | lung | KRAS | G12C | 0.015 | >10 | 2.050 |

| LoVo | colon | KRAS | G13D | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.179 |

| PANC-1 | pancreas | KRAS | G12D | 0.009 | 0.708 | 0.535 |

| HCT116 | colon/rectum | KRAS | G13D | 0.026 | 0.549 | 8.762 |

| Calu-6 | lung | KRAS | Q61K | 0.007 | 0.555 | 0.508 |

| A549 | lung | KRAS | G12C | 0.053 | >10 | 2.350 |

| NCI-H460 | lung | KRAS | Q61H | 0.296 | >10 | 3.3000 |

| CFPAC-1 | pancreas | KRAS | G12V | 0.576 | 3.601 | >10 |

| SK-MEL-2 | skin | NRAS | Q61R | 0.003 | 0.089 | 0.137 |

| Hep G2 | liver | NRAS | Q61L | 0.058 | 0.038 | 0.170 |

| A2780 | ovary | PTEN | N/A | 0.008 | 0.294 | 0.266 |

| LNCaP | prostate | PTEN | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| PC-3 | prostate | PTEN | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| U-87 MG | brain | PTEN | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| MCF7 | breast | PIK3CA | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| T-47D | breast | PIK3CA | N/A | >10 | >10 | 9.566 |

| NCI-H1975 | lung | EGFR | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| BT-474 | breast | HER2 | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| 786-O | kidney | Other | N/A | >10 | >10 | >10 |

N/A, not applicable.

Table 2.

IC50 mean values (μM) of ASN007 against different lymphoma cell lines

| Cell line | IC50 | Cell line | IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA46 | >10 | SU-DHL-8 | 2.4 |

| EB1 | >10 | SU-DHL-1 | 2.3 |

| Daudi | >10 | U-2932 | 2.3 |

| L-428 | >10 | DB | 1.7 |

| SUP-M2 | >10 | Ramos | 1.8 |

| REC-1 | 7.6 | SU-DHL-10 | 1.7 |

| HBL-1 | 7.4 | Ri-1 | 1.6 |

| JVM-2 | 5.7 | OCI-Ly10 | 1.5 |

| OCI-Ly3 | 5.5 | JeKo-1 | 1.4 |

| BJAB | 4.3 | MAVER-1 | 1.3 |

| KARPAS-299 | 4.1 | SU-DHL-6 | 1.2 |

| Raji | 3.1 | Z-138 | 0.5 |

| TMD8 | 3.0 | OCI-Ly19 | 0.4 |

| SU-DHL-4 | 2.9 | U-2973 | 0.3 |

| JVM-13 | 2.7 | MINO | 0.2 |

| KM-H2 | 2.6 | NU-DHL-1 | 0.1 |

In vivo activity of ASN007

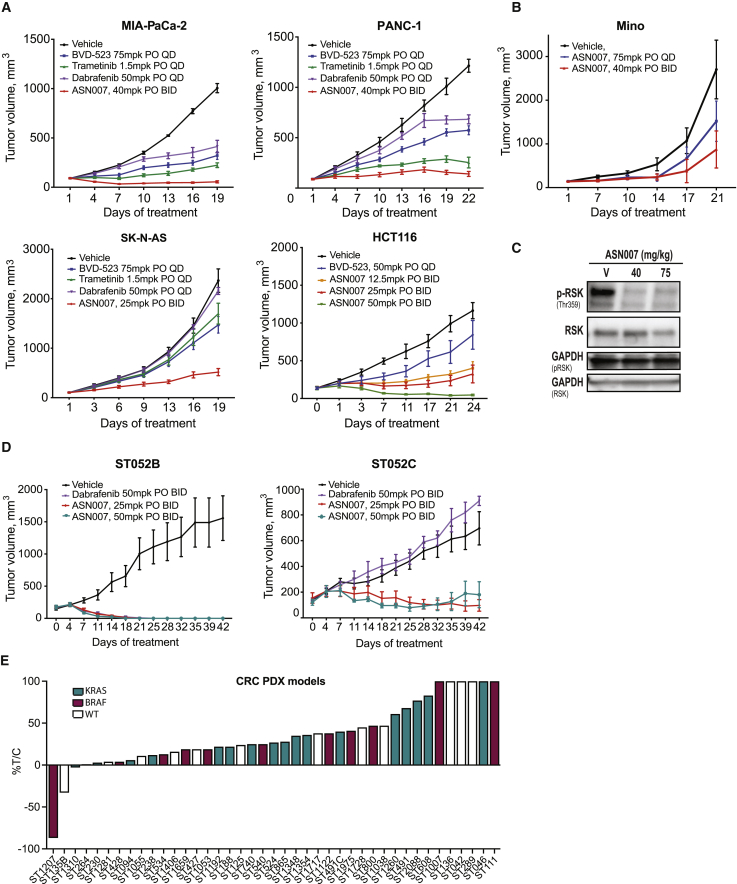

ASN007 activity was also evaluated in four different human tumor xenograft mouse models harboring either KRAS or NRAS mutations: (1) HCT116, a colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line with a KRASG13D mutation; (2) Panc-1, a pancreatic adenocarcinoma model with a KRASG12D mutation; (3) MIA PaCa-2, a pancreatic adenocarcinoma model with a KRASG12C mutation; and (4) SK-N-AS, a neuroblastoma model with a NRASQ61K mutation. In all four models, ASN007 demonstrated strong antitumor efficacy (Figure 3A) without body weight loss (Figure S2A). Similarly, ASN007 showed a strong tumor growth inhibition in MINO, a mantle cell lymphoma model with a NRASG13D mutation (Figure 3B). In a pharmacodynamic assay, ASN007 decreased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 target proteins RSK and MSK (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

In vivo activity of ASN007 in mouse xenografts and PDX models

(A) MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1, SK-N-AS, and HCT116 tumor cells were implanted, and when tumors reached ~100 mm3 in size, mice were treated with either vehicle or ASN007 at the indicated doses and schedules. BID, twice per day; PO, per os (oral) administration; QD, once per day. Error bars represent means ± SEMs (n > 8 per treatment group).

(B) Activity of two different doses of ASN007 in a mantle cell lymphoma xenograft model using the MINO cell line. Error bars represent means ± SEMs (n >8 per treatment group).

(C) Representative western blot analysis of total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 and RSK in tumor extracts from the MINO xenograft at the end of treatment (75 mg/kg, QD, or 40 mg/kg, BID). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control.

(D) PDX model derived from a melanoma patient before (ST052B) and after relapsing on vemurafenib treatment (ST052C). In the ST052C model, treatment with ASN007 (25 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg PO, BID) remained effective while therapy with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib showed no efficacy. Error bars represent means ± SEMs (n > 5 per treatment group).

(E) Tumor growth inhibition by ASN007 (40 mg/kg PO, BID) in a panel of colorectal cancer PDX models treated for 22 to 35 days, depending on the model. Each bar represents 1 model. The color of the bar denotes the mutation status of BRAF and KRAS genes; magenta = BRAF mutant, green = KRAS mutant, and white = wild type for both BRAF and KRAS. In all in vivo efficacy studies except for the HCT116 model, the besylate (salt correction factor 1.33) or mandelate salt form (salt correction factor 1.32) of ASN007 was used. However, the freebase form of ASN007 was used for the study involving the HCT116 model.

The efficacy of ASN007 was evaluated against a panel of 41 patient-derived xenograft (PDX) colorectal cancer mouse models (Figure 3E; Table S3). The panel included 17 tumors with KRAS mutations (including G12C, G12D, G12S, G12V, and G13D), 11 with the BRAFV600E mutation, and 13 with wild-type BRAF and KRAS genes. Overall, treatment with ASN007 resulted in at least 30% tumor growth inhibition in 33 of 41 models (80%) compared to mice treated with vehicle. ASN007 was highly effective in tumors harboring KRAS mutations, as tumor growth inhibition was observed in 16 of 17 models, irrespective of the KRAS subtype mutations. In two BRAFV600E mutant models, ASN007 induced tumor regression below baseline tumor volumes. Using a panel of 45 genes known to be frequently altered in human tumors analyzed by exon sequencing, we observed that most models with mutations in the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway responded to ASN007 treatment (Figure S2B). However, some models with wild-type status of KRAS or BRAF genes also showed sensitivity to ASN007 treatment. Additional studies involving genomics and proteomics would help in understanding the activity of ASN007 in these wild-type models.

In addition, a pair of PDX models were derived from a melanoma patient with a BRAFV600E mutation, one before initiating treatment with vemurafenib and the second established after disease progression while on vemurafenib. In the vemurafenib-sensitive PDX model (ST052B), dabrafenib (50 mg/kg per os [PO] twice per day [BID]) and ASN007 (25 or 50 mg/kg PO BID) demonstrated similar antitumor activity (Figure 3D). In the vemurafenib-resistant PDX model (ST052C), ASN007 (25 or 50 mg/kg PO BID) maintained its antitumor activity with no significant loss of body weight (Figure S2C), whereas dabrafenib showed no efficacy. Thus, ASN007 was effective in both vemurafenib-sensitive and -resistant melanoma PDX models, suggesting that the compound can be used to treat patients with BRAF mutant melanoma after the failure of prior BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy.

The PI3K inhibitor copanlisib enhances the antitumor activity of ASN007

Interlinked biological network systems such as the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K pathways are reported to be highly responsive to external perturbations, especially when combinational therapies targeting both pathways are used.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 To explore the impact of ERK and PI3K simultaneous inhibition in our models, ASN007-sensitive or ASN007-resistant lymphoma and solid tumor cell lines were treated with different concentrations of ASN007 and the PI3K inhibitor copanlisib.

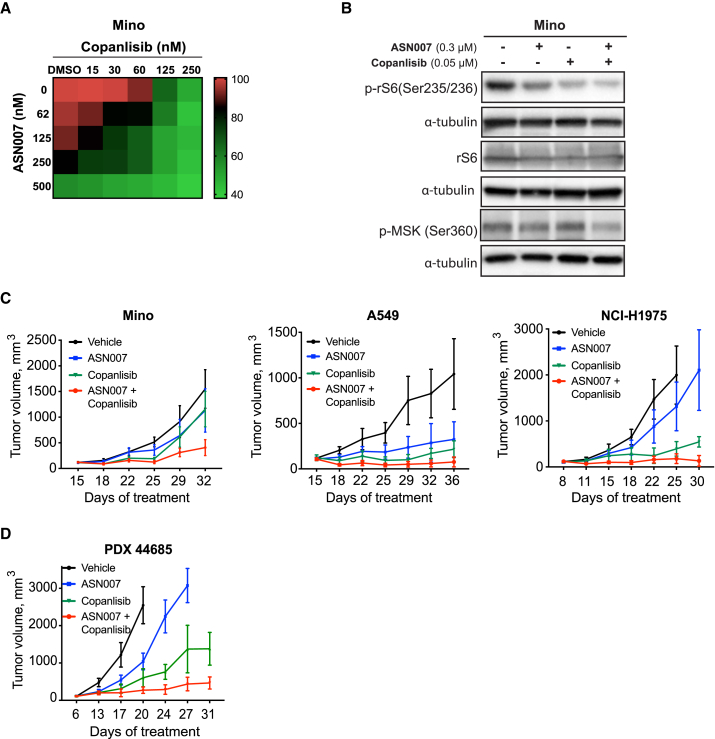

Combinational therapy enhanced the antiproliferative activity of ASN007 in a variety of lymphoma and solid tumor cell lines compared to either compound alone (Figures 4A, S3A, and S3B). The inhibition of proliferation was associated with the reduced activity of ERK and PI3K downstream targets MSK and ribosomal protein S6 (rS6), respectively. The combination of ASN007 and copanlisib resulted in the suppression of MSK and rS6 phosphorylation to lower levels than are seen with either single-agent treatment (Figure 4B). A similar effect was observed in three different xenograft models (Figure 4C) and in a mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) PDX model (Figure 4D). In all of the models tested, combined therapy led to an enhanced treatment efficacy shown by delayed tumor growth without compromising the body weight of the animals (Figures S3C and S3D).

Figure 4.

The combination of ASN007 and the PI3K inhibitor copanlisib results in enhanced antiproliferative activity in vitro and enhanced tumor growth inhibition in vivo

(A) Drug matrix heatmap of the enhanced antiproliferative effect when ASN007 is combined with the PI3K inhibitor copanlisib in an MCL cell line, MINO. Heatmap grids correspond to the mean of three independent experiments measured by the MTS assay.

(B) Western blot analysis of total and phosphorylated levels of rS6 and MSK after 72 h of treatment with ASN007 (0.3 μM), copanlisib (0.05 μM), or the combination of both compounds in MINO cells. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

(C) Combination of ASN007 and copanlisib results in enhanced efficacy in MINO and two lung carcinoma (A549, NCI-H1975) xenograft tumor models. Error bars represent means ± SEMs (n > 8 per treatment group).

(D) Combination of ASN007 and copanlisib results in enhanced efficacy in an MCL PDX mouse model (PDX44685).

Doses administered: ASN007 (40 mg/kg PO, BID in all four models); copanlisib (14 mg/kg for MINO, NCI-H1975, and PDX 44685, and 10 mg/kg for A549, 2 days on followed by 5 days off, intraperitoneally [i.p.]). Error bars represent means ± SEMs (n > 8 per treatment group).

Discussion

BRAF and MEK inhibitors are the only approved agents targeting RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling activity.18,25 However, a common feature of these inhibitors is the trigger of compensatory signaling such as the reactivation of ERK1/2, leading to treatment escape and drug resistance.2,26 These observations suggest that therapeutic targeting of ERK1/2 may have an advantage over inhibiting upstream targets such as MEK or BRAF. In this study, we describe the discovery and characterization of ASN007, an orally bioavailable and potent small-molecule inhibitor of ERK1 and ERK2 kinases.

ASN007 is a reversible and ATP-competitive inhibitor of ERK1/2 kinases. In cell-free assays, ASN007 had an IC50 of 2 nM against ERK1 and ERK2 kinases. ASN007 demonstrated antiproliferative activity in an extended panel of solid tumor and lymphoma cell lines, which is associated with the durable blockade of ERK target phosphorylation. Furthermore, ASN007 demonstrated preferential activity in a variety of tumor types that harbored mutations in BRAF, KRAS, or RAS, providing a potential selection biomarker in clinical trials. In cell lines harboring mutations in BRAF or RAS, ASN007 demonstrated superior efficacy when compared with other ERK1/2 inhibitors (ulixertinib/BVD-523 and ravoxertinib/GDC-0994).

ASN007 showed potent inhibition of cell proliferation in a panel of cell lines harboring various subtype mutations of KRAS. The subtype mutations include G12C, G12V, G12D, G13D, Q61K, Q61L, Q61H, and Q61R. Several KRAS inhibitors, such as AMG 510, MRTX849, and ARS-3248, are being evaluated in clinical trials (NCT04185883, NCT03785249, and NCT04006301).27,28 However, these compounds are very specific to the G12C mutation subtype27 and do not show activity against other mutant forms of KRAS. Therefore, unlike the KRASG12C selective inhibitors, ASN007 may have activity in tumors with a broad range of KRAS mutation subtypes.

Despite a remarkable initial response to both BRAF and MEK1/2 inhibitors, most cancer patients subsequently relapse due to acquired resistance.29,30 Although multiple mechanisms have been identified to mediate this acquired resistance, the ERK1/2 node seems to be the common point of reactivation of the RAS/MAPK pathway.31,32 This makes ERK1/2 ideal targets for overcoming the resistance to both BRAF and MEK1/2 inhibitors. ASN007 demonstrated strong efficacy in a melanoma PDX tumor model that was resistant to BRAF and MEK1/2 inhibitors. Although the mechanism of resistance to BRAF inhibition in this model is not well characterized, previous studies demonstrate that resistance to BRAF inhibitors is associated with the activation of ERK1/2.33,34 Therefore, we hypothesized that inhibiting ERK1/2 kinases by ASN007 would be effective in dabrafenib (BRAF inhibitor)-resistant tumor models. Our data suggest that ASN007 could overcome the resistance to BRAF and MEK1/2 inhibitors, and thus, ASN007 may be able to provide a therapeutic option to patients who relapsed on these agents.

Crosstalk between the RAS/MEK/ERK and the PI3K signaling pathways has been reported.35,36 In addition, MEK inhibition has been shown to cause PI3K activation, and PI3K inhibition has been demonstrated to cause ERK activation.2,37,38 These observations provided an opportunity to develop a mechanism-based combination strategy combining ASN007 with PI3K inhibitors, such as copanlisib, which was recently approved by regulatory agencies for the treatment of relapsed follicular lymphoma.39,40 Our data show that the combination of copanlisib and ASN007 was more effective than either drug alone, allowing for the dose reduction of each agent, which may improve treatment tolerance. Moreover, the ASN007 plus copanlisib combination was effective in a variety of tumor models, including breast, lung, and lymphoma cell-line-derived xenografts, in addition to a PDX-model derived from an MCL patient.

In summary, our preclinical data provide a rationale for evaluating ASN007 as a single agent or in combination with PI3K inhibitors in cancer patients, especially those with tumors harboring mutations in RAS and BRAF genes. A phase I study has been conducted in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring BRAF and KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS mutations, and early results suggest that ASN007 is well tolerated with durable clinical activity lasting up to >12 months (NCT03415126).41

Limitations of the study

Dose-limiting cytotoxicity remains a challenge with kinase inhibitors. Although we demonstrate that ASN007 performs well by oral delivery either twice or once daily and in combination with a PI3K inhibitor, our study was not designed to address additional organ or systemic toxicities. Further studies should be performed to understand the mechanism of action through which ASN007 is able to overcome resistance to BRAF inhibitors in the melanoma PDX model.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Phospho-p90RSK (Thr359) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 8753; RRID: AB_2783561 |

| RSK1 | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 9333; RRID: AB_2181177 |

| p-MSK (S360) | Abcam | Cat# ab81294; RRID: AB_1640701 |

| MSK2 | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 3679; RRID: AB_2181641 |

| Phospho-FRA1 (Ser265) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 3880; RRID: AB_2106922 |

| FRA1 (D80B4) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 5281; RRID: AB_10557418 |

| α-tubulin | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 3873; RRID: AB_1904178 |

| β-Actin | Sigma | Cat# A5316; RRID: AB_476743 |

| GAPDH (D16H11) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 5174; RRID: AB_10622025 |

| Phospho-GSK3 β (Ser9) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 9322; RRID: AB_2115196 |

| Phospho-GSK3 β (Ser21) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 8452; RRID: AB_10860247 |

| S6 Ribosomal Protein (5G10) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 2217; RRID: AB_331355 |

| Phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein (Ser235/236) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 4856; RRID: AB_2181037 |

| β-catenin | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 9582; RRID: AB_823447 |

| Goat Anti-mouse IgG HRP Conjugate | Biorad | Cat# 170-6516; RRID: AB_11125547 |

| Goat Anti-rabbit IgG HRP Conjugate | Biorad | 170-6515; RRID: AB_11125142 |

| Biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG | Vector Labs | Cat# BA-5000; RRID: AB_2336126 |

| Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Vector Labs | Cat# PK-6101; RRID: AB_2336820 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| ASN007 | Asana | N/A |

| Copanlisib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2802 |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide | Sigma | Cat# D4540 |

| Palbociclib | Selleckchem | Cat# S1579 |

| Ulixertinib (BVD-523) | Selleckchem | Cat# S7854 |

| SCH772984 | Selleckchem | Cat# S7101 |

| Ravoxertinib (GDC-0994) | Selleckchem | Cat# S7554 |

| Trametinib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2673 |

| Dabrafenib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2807 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay | Promega | Cat# G5430 |

| Supersignal West Dura extended duration substrate | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 34076 |

| 3x Blue Loading buffer | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 56036S |

| 30x reducing agent (1.25M DTT) | Cell signaling technology | Cat# 14265S |

| Matrigel | Thermo Fisher | Cat# CB-40234C |

| Annexin V FITC Apoptosis detection Kit I | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556547; RRID: AB_2869082 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| SU-DHL-6 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-572, RRID:CVCL_2206 |

| JeKo-1 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3006, RRID:CVCL_1865 |

| Mino | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3000, RRID:CVCL_1872 |

| OCI-Ly19 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-528, RRID:CVCL_1878 |

| U-2973 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-642, RRID:CVCL_1898 |

| SU-DHL-4 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-495, RRID:CVCL_0539 |

| TMD8 | Dr. R.E. Davis lab | MDACC |

| REC-1 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3004, RRID:CVCL_1884 |

| SU-DHL-8 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-573, RRID:CVCL_2207 |

| MAVER-1 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-717, RRID:CVCL_1831 |

| Ri-1 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-585, RRID:CVCL_1885 |

| U-2932 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-633, RRID:CVCL_1896 |

| HBL-1 | Dr. R.E. Davis lab | MDACC |

| Z-138 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3001, RRID:CVCL_B077 |

| NU-DHL-1 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-583, RRID:CVCL_1876 |

| CA46 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1648, RRID:CVCL_1101 |

| EB1 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-60, RRID:CVCL_2027 |

| Daudi | ATCC | Cat# CCL-213, RRID:CVCL_0008 |

| L-428 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-197, RRID:CVCL_1361 |

| SUP-M2 | Dr. R.E. Davis lab | MDACC |

| JVM-2 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3002, RRID:CVCL_1319 |

| OCI-Ly3 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-761, RRID:CVCL_8800 |

| BJAB | Dr. R.E. Davis lab | MDACC |

| KARPAS-299 | Dr. R.E. Davis lab | MDACC |

| Raji | ATCC | Cat# CCL-86, RRID:CVCL_0511 |

| JVM-13 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3003, RRID:CVCL_1318 |

| KM-H2 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-8, RRID:CVCL_1330 |

| DB | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-539, RRID:CVCL_1168 |

| Ramos | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1596, RRID:CVCL_0597 |

| SU-DHL-10 | DSMZ | Cat# ACC-576, RRID:CVCL_1889 |

| OCI-Ly10 | DSMZ | RRID:CVCL_8795 |

| HT-29 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-38, RRID:CVCL_0320 |

| A375 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1619, RRID:CVCL_0132 |

| Colo205 | ATCC | Cat# CCL-222, RRID:CVCL_0218 |

| T24 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-4, RRID:CVCL_0554 |

| NIC-H2122 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-5985, RRID:CVCL_1531 |

| LoVo | ATCC | Cat# CCL-229, RRID:CVCL_0399) |

| Panc1 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1469, RRID:CVCL_0480 |

| HCT116 | ATCC | Cat# CCL-247, RRID:CVCL_0291 |

| Calu6 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-56, RRID:CVCL_0236 |

| A549 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-7909, RRID:CVCL_0023 |

| NIC-H460 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-177, RRID:CVCL_0459 |

| CFPac1 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1918, RRID:CVCL_1119 |

| SK-Mel-2 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-68, RRID:CVCL_0069 |

| HepG2 | ATCC | Cat# HB-8065, RRID:CVCL_0027 |

| A2780 | Millipore Sigma | Cat# 93112519, RRID:CVCL_0134 |

| LnCAP | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1740, RRID:CVCL_1379 |

| PC3 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1435, RRID:CVCL_0035 |

| U87MG | ATCC | Cat# HTB-14, RRID:CVCL_0022 |

| MCF7 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-22, RRID:CVCL_0031 |

| T47D | ATCC | Cat# HTB-133, RRID:CVCL_0553 |

| NIC-H1975 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-5908, RRID:CVCL_1511 |

| BT474 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-20, RRID:CVCL_0179 |

| 786-0 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1932, RRID:CVCL_1051 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| NSG mice | Jackson Laboratories | N/A |

| Athymic NU(NCr)-Foxn1 nude | Vivo Biotech | Cat# CRL:490; RRID: IMSR_CRL:490 |

| DLFB-44685 | Dana-Farber Cancer institute | Stock # 005557; RRID: IMSR_JAX005557 |

| ST052B | START Center for Cancer Care | N/A |

| ST052C | START Center for Cancer Care | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Graphpad Prism 8.0 | Graphpad software | N/A |

| CellQuest Pro | BD Biosciences | 6.0 |

| FlowJo | BD Biosciences | 10 |

| Image lab | Biorad | 4.0.1 |

| TREEspot Compound Profile Visualization Tool | DiscoverX | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Anas Younes (anas.younes@astrazeneca.com).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study. Kinome screening data generated for this study are summarized on Table S1.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell lines

The human mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) cell lines (REC-1, JeKo-1, Z-138, Mino, JVM-2, JVM-13), Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cell lines (Raji, EB1, DaudiI, Ramos, and CA46) and solid tumors cell lines were obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection). Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL)-derived cell lines (SU-DHL-4, SU-DHL-6, SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-10 OCI-Ly10, DB, NU-DHL-1, U-2973, OCI-Ly3, U-2932, Ri-1 and OCI-Ly19), Hodgkin’s cell lines (L-428 and KM-H2) and the MCL cell line MAVER-1 were obtained from the DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Department of Human and Animal Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany). The cell lines BJAB (BL), HBL-1 and TMD8 (DLBCL), SUP-M2, SU-DHL-1 and KARPAS-299 (Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL)-cell lines) were provided by Dr. R.E. Davis (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). H1975 cells were provided by Dr. M. Ruscetti (Scott Lowe lab, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). Lymphoma cell lines were authenticated at the Integrated Genomic Operation Core (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). Cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10%–20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, GE Healthcare Life Sciences), 1% L-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin in a humid environment of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Mutations were annotated according to CCLE: Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (https://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle/home).

Human specimens

Melanoma and colorectal tumor specimens used for PDX were established from primary lesions in patients with cutaneous melanoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma at XenoSTART, San Antonio, US. Mantle cell lymphoma specimen were obtained from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, US. Mantle Cell Lymphoma PDX model were utilized for evaluation of ASN007 by the Antitumor Assessment Core at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). All PDX were developed and utilized in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols at XenoSTAR, MSKCC and Dana-Faber and the United States Department of Health and Human Services. Specific informed consent for PDX model generation was obtained from all patients in the respective institutions of origin (XenoSTART and Dana-Farber). Clinicopathological characteristics PDX model used in this study are summarized in Table S3.

Animals

Experiments were performed in female athymic NU(NCr)-Foxn1 nude mice obtained from Envigo, Charles River Laboratories or Vivo Biotech. The animals were housed in individually ventilated cages (maximum of 4 animals/cage) with 12 hours dark, 12 hours light conditions. The animals were fed food and water ad libitum. Temperature and relative humidity were maintained at 20 ± 2°C and 65%, respectively. Female NSG mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory. All animal studies were reviewed and approved by IACUC at Jubilant BioSys, MSKCC and at XenoSTART, Center for Cancer Care. All mice were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) on the care, welfare, and treatment of laboratory animals. All experiments met the standards of the Association for the AAALAC, the United States Department of Health and Human Services, and all local and federal animal welfare laws.

Experimental in vivo tumor models

Mice randomized 10 mice per treatment groups were injected subcutaneously with specific cell lines, or patient derived (PDX) tumors, which were grown to approximately 100 or 150 mm3, before they were treated with specified single agents or combinations. Animal body weight and tumor length (L), width (W), and height (H) were measured twice weekly before and during treatment periods on each mouse and then used to calculate tumor volume using the formula (L × W × H)/2. Upon completion of the experiment, tumors were harvested and processed for western blot analysis.

The efficacy of ASN007 in tumor growth inhibition in PDX was evaluated in a panel of colorectal 41 cancer PDX models. The study included wild-type (n = 13), BRAFV600E mutant (n = 10) and KRAS mutant models (n = 18). Out of 18 KRAS mutant models, six of them had PIK3CA mutations. either vehicle group or ASN007 treatment group were treated orally with vehicle or with ASN007 at 25 mg/kg PO, BID for up to 35 days. In all in vivo efficacy studies except for the HCT116 model, the besylate (MW = 632.12) or mandelate (MW = 626.09) salt form of ASN007 was used. However, the free base form of ASN007 (MW = 473.94) was used for the HCT116 model.

Method details

ERK1/ERK2 homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) enzymatic assay

Test compounds were serially diluted by half-log dilutions, with concentrations ranging from 0.0005 μM to 10 μM in HTRF assay buffer (50 mM Tris pH = 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20); 20 μL of substrate-ATP mix was added to each well of the assay plate followed by adding 10 μL of enzyme mix to each well. Plates were incubated for 60 min at room temperature with shaking. The HTRF mix was prepared and 75 μL was added to the HTRF plate. After the incubation, 10 μL of the reaction mixture was transferred to the HTRF assay plate and incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature with shaking. Plates were read using the PHERAstar microplate reader in homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) mode. The IC50 values were subsequently determined using a sigmoidal dose-response curve (variable slope) in GraphPad Prism 5 software.

In vitro kinase profiling

ASN007 was tested against a panel of 335 protein kinases encompassing both serine/threonine, tyrosine kinases and lipid protein kinases (KinaseProfiler™, Eurofins) in a radiometric assay at a fixed concentration of 1 uM. The residual activity for each kinase was determined using the formula: residual activity (%) = 100 X [(cpm of compound-low control) / (high control – low control)]. The dendrogram was generated using the web tool, TREESpot™, provided by DiscoverX. The 50% inhibitory concentration values (IC50) of ASN007 were determined for the top 22 kinases, which showed > 75% inhibition at 1 μM, selected from the screening panel using 10-point dose response curves at Reaction Biology Corporation.

Cell-based target inhibition

Target inhibition by ASN007 was determined using the solid phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that detects the levels of RSK1 when phosphorylated at Ser380 position. In this assay, B-RAFV600E mutant HT29 colon cancer cells were used to test the free base of ASN007 with a potency of 0.007 μM (7 nM). HT29 cells were seeded (60,000 cells/well) in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 overnight and then treated with desired compound dilutions for 2 hours. The assay medium was removed, and cells were rinsed once with ice-cold 1X PBS. Then, 0.070 mL ice-cold 1X cell lysis buffer containing 1 mM of the serine protease inhibitor phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was added to each well and the plate was incubated on a shaker for 2.5 hours at 4°C. The plate was then centrifuged for 20 minutes (4000 rpm) at 4°C and the supernatant transferred to a new plate. Cell lysates were diluted with sample diluent at a ratio of 1:1. The ELISA was carried out following the manufacturer’s protocol. The IC50 values were subsequently determined using a sigmoidal dose-response curve (variable slope) in GraphPad Prism 7 software.

Cell proliferation assays

Adherent cells were seeded (5,000 cells/well) in 96-well tissue culture plates and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 16 to 24 hours and subsequently treated with different compounds. Compound concentrations ranged from 0.0005 to 10 μM prepared in 3-fold serial dilutions. The plates were then incubated for 72 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Then Alamar Blue reagent (final concentration 1X) was added to each well and incubated for 1 to 3 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The plates were read on a fluorescence reader at 540 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths. The IC50 values were subsequently determined using a sigmoidal dose-response curve (variable slope) in GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Suspension cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 25,000 cells per 100 μL per well or in 24-well plates at 250,000 cells per 1 mL per well with either vehicle (DMSO 0.1%) or increasing concentrations of compound for 24, 48, and 72 hours. Cell viability was assessed with the nonradioactive cell proliferation MTS assay, using CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega). MTS was added to the culture medium at 1:5 ratios, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was recorded at 490 nm with a 96-well plate reader (Bio-Rad) (Molecular Devices, SpectraMax M3). IC50 concentrations were calculated from MTS results using GraphPad Prism 7 software.

Western blotting

Preparation of cellular protein lysates or tumor samples was performed by using the Cell Signaling lysis buffer (9803) according to the manufacturer’s extraction protocol. Protein quantitation was done using the Direct Detect system (Millipore) or Coomassie Blue reagent following the recommended protocol. A total of 30 μg of protein was denatured in Laemmli buffer supplemented with DTT (10%) at 95°C for 5 min. Western immunoblotting was performed using the Bio-Rad system (TGX 4%–15% gels) or ExpressPlus PAGE 4%–12% gel was assembled in an XCell II Blot module (Invitrogen, Catalog no. EI9051). Transfer was performed for 7 minutes using the Trans Blot turbo system (Bio-Rad) onto PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were incubated overnight in 10 mL of blocking buffer (5% BSA in 1X PBS) containing primary antibody. Secondary antibody incubation was done in blocking buffer containing specific IRDye or HRP-conjugate secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature and protected from light. Images were acquired by using the Bio-Rad Imaging Chemidoc MP system or Li-Cor Odyssey Imaging system.

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

To determine the effect of ASN007 treatment on cell cycle, cell lines were cultured with or without the ERK1/2 inhibitor for 24 to 72 hours. Cells were collected and then stained with propidium iodide (PI)/RNase staining solution (Cell Signaling, #4087) at room temperature for 15 minutes. Flow cytometric data was acquired on a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using CellQuest Pro Version 6.0. Propidium iodide was excited by the 488 nm laser and fluorescence emission was measured in fluorescence parameter 3 (FL3) – with the standard 670LP filter. Greater than 10,000 events were acquired. Data Analysis: Doublets were excluded by gating out high FL3- W (width) cells.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Procedures to determine the effects of certain conditions on cell proliferation were performed in 3 independent experiments. The two-tailed Student’s t test and Wilcoxon rank test were used to estimate the statistical significance of differences between results from the 3 experiments. Significance was set at p < 0.05. PRISM software was used for the statistical analyses. For synergy estimation, ΔBliss excess was calculated as shown previously.42 Bliss expectation was calculated as A + B − (A × B), where A and B denote the fractional responses from drugs A and B given individually. The difference between Bliss expectation and observed proliferation inhibition of the combination of drugs A and B at the same doses define ΔBliss excess.

Acknowledgments

We thank the integrated Genomics Operation Core for the cell lines and PDX samples sequencing and members at the Antitumor Assessment Core for technical assistance. We thank Dhanalakshmi Sivanandhan, Sreekala Nair, Chandru G, Pradeep N, Ramachandraiah Gosu, Krishnakumar V, Sameer Mahmood, Mohd. Zainuddin, and Polina Sai Babu (Jubilant Biosys, Bengaluru, India) for assistance in designing and conducting the experiments. We also wish to thank Michael Wick, Jun Ma, and Morgan Harris from XenoSTART (formerly START) for their help with in vivo studies involving melanoma and colorectal cancer PDX models. This work was supported in part by the NIH MSK SPORE in Lymphoma (P50 CA192937), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Specialized Center of Research Program (7014-17), Institutional Core Grant (P30 CA008748), and the George Ohrstrom Foundation.

Author contributions

A.P., A.Y., and S.R. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. A.P., M.D.S.F., and Z.A. conducted the experiments. A.K. and V.S. conducted the statistical analysis of the data. E.d.S., S.T., R.A.S., S.G., and L.D. supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

A.Y. has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Abbvie, Biopath, Curis, Epizyme, Janssen, Merck, Roche, Takeda, and Xynomic and has received research support from Janssen, Curis, Merck, BMS, Syndax, and Roche. S.T., S.G., and L.D. are employees and shareholders of Asana BioSciences. R.A.S. is a shareholder in and consultant to Asana BioSciences. S.T., R.A.S., and S.R. are inventors on three patents covering ASN007 and related compounds and their use in the treatment of cancer. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 20, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100350.

Contributor Information

Scott Thompson, Email: scott.thompson@asanabio.com.

Anas Younes, Email: anas.younes@astrazeneca.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N., Velculescu V.E., Zhou S., Diaz L.A., Jr., Kinzler K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samatar A.A., Poulikakos P.I. Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: promises and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:928–942. doi: 10.1038/nrd4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montagut C., Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wortzel I., Seger R. The ERK Cascade: Distinct Functions within Various Subcellular Organelles. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:195–209. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh N., Shuck R.L., Nguyen T.A., Herron A., Donehower L.A. Mouse tissues that undergo neoplastic progression after K-Ras activation are distinguished by nuclear translocation of phospho-Erk1/2 and robust tumor suppressor responses. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012;10:845–855. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhillon A.S., Hagan S., Rath O., Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–3290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McArthur G.A., Chapman P.B., Robert C., Larkin J., Haanen J.B., Dummer R., Ribas A., Hogg D., Hamid O., Ascierto P.A. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAF(V600E) and BRAF(V600K) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman P.B., Hauschild A., Robert C., Haanen J.B., Ascierto P., Larkin J., Dummer R., Garbe C., Testori A., Maio M., BRIM-3 Study Group Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falchook G.S., Lewis K.D., Infante J.R., Gordon M.S., Vogelzang N.J., DeMarini D.J., Sun P., Moy C., Szabo S.A., Roadcap L.T. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782–789. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delord J.P., Robert C., Nyakas M., McArthur G.A., Kudchakar R., Mahipal A., Yamada Y., Sullivan R., Arance A., Kefford R.F. Phase I Dose-Escalation and -Expansion Study of the BRAF Inhibitor Encorafenib (LGX818) in Metastatic BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:5339–5348. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larkin J., Ascierto P.A., Dréno B., Atkinson V., Liszkay G., Maio M., Mandalà M., Demidov L., Stroyakovskiy D., Thomas L. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1867–1876. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez J.N., Wang T., Cohen M.S. BRAF and MEK Inhibitors: Use and Resistance in BRAF-Mutated Cancers. Drugs. 2018;78:549–566. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0884-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauschild A., Grob J.J., Demidov L.V., Jouary T., Gutzmer R., Millward M., Rutkowski P., Blank C.U., Miller W.H., Jr., Kaempgen E. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris E.J., Jha S., Restaino C.R., Dayananth P., Zhu H., Cooper A., Carr D., Deng Y., Jin W., Black S. Discovery of a novel ERK inhibitor with activity in models of acquired resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:742–750. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blake J.F., Burkard M., Chan J., Chen H., Chou K.J., Diaz D., Dudley D.A., Gaudino J.J., Gould S.E., Grina J. Discovery of (S)-1-(1-(4-Chloro-3-fluorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl)-4-(2-((1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5-yl)amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)pyridin-2(1H)-one (GDC-0994), an Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) Inhibitor in Early Clinical Development. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:5650–5660. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar R., Suresh P.S., Rudresh G., Zainuddin M., Dewang P., Kethiri R.R., Rajagopal S., Mullangi R. Determination of ulixertinib in mice plasma by LC-MS/MS and its application to a pharmacokinetic study in mice. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016;125:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidger A.M., Sipthorp J., Cook S.J. ERK1/2 inhibitors: new weapons to inhibit the RAS-regulated RAF-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 pathway. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;187:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F., Yang X., Geng M., Huang M. Targeting ERK, an Achilles’ Heel of the MAPK pathway, in cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2018;8:552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehár J., Krueger A., Zimmermann G., Borisy A. High-order combination effects and biological robustness. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:215. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ning C., Liang M., Liu S., Wang G., Edwards H., Xia Y., Polin L., Dyson G., Taub J.W., Mohammad R.M. Targeting ERK enhances the cytotoxic effect of the novel PI3K and mTOR dual inhibitor VS-5584 in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44295–44311. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng X., Liu Y., Zhu S., Peng X., Li H., Jiao W., Lin P., Zhang Z., Qiu Y., Jin M. Co-targeting PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK pathways leads to an enhanced antitumor effect on human hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019;145:2921–2936. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-03047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Won J.K., Yang H.W., Shin S.Y., Lee J.H., Heo W.D., Cho K.H. The crossregulation between ERK and PI3K signaling pathways determines the tumoricidal efficacy of MEK inhibitor. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;4:153–163. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chappell W.H., Steelman L.S., Long J.M., Kempf R.C., Abrams S.L., Franklin R.A., Bäsecke J., Stivala F., Donia M., Fagone P. Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget. 2011;2:135–164. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y.L., Maachani U.B., Schweitzer M., Singh R., Wang M., Chang R., Souweidane M.M. Dual Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK Pathways Induces Synergistic Antitumor Effects in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Cells. Transl. Oncol. 2017;10:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yaeger R., Corcoran R.B. Targeting Alterations in the RAF-MEK Pathway. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:329–341. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibney G.T., Messina J.L., Fedorenko I.V., Sondak V.K., Smalley K.S. Paradoxical oncogenesis--the long-term effects of BRAF inhibition in melanoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013;10:390–399. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallin J., Engstrom L.D., Hargis L., Calinisan A., Aranda R., Briere D.M., Sudhakar N., Bowcut V., Baer B.R., Ballard J.A. The KRAS(G12C) Inhibitor MRTX849 Provides Insight toward Therapeutic Susceptibility of KRAS-Mutant Cancers in Mouse Models and Patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:54–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanman B.A., Allen J.R., Allen J.G., Amegadzie A.K., Ashton K.S., Booker S.K., Chen J.J., Chen N., Frohn M.J., Goodman G. Discovery of a Covalent Inhibitor of KRAS(G12C) (AMG 510) for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:52–65. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salama A.K., Flaherty K.T. BRAF in melanoma: current strategies and future directions. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:4326–4334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh S.J., Rizos H., Scolyer R.A., Long G.V. Resistance to combination BRAF and MEK inhibition in metastatic melanoma: Where to next? Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;62:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Allen E.M., Wagle N., Sucker A., Treacy D.J., Johannessen C.M., Goetz E.M., Place C.S., Taylor-Weiner A., Whittaker S., Kryukov G.V. The genetic landscape of clinical resistance to RAF inhibition in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:94–109. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hazar-Rethinam M., Kleyman M., Han G.C., Liu D., Ahronian L.G., Shahzade H.A., Chen L., Parikh A.R., Allen J.N., Clark J.W. Convergent Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome the Heterogeneity of Acquired Resistance in BRAFV600E Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:417–427. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan R.J., Flaherty K.T. Resistance to BRAF-targeted therapy in melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:1297–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagle N., Van Allen E.M., Treacy D.J., Frederick D.T., Cooper Z.A., Taylor-Weiner A., Rosenberg M., Goetz E.M., Sullivan R.J., Farlow D.N. MAP kinase pathway alterations in BRAF-mutant melanoma patients with acquired resistance to combined RAF/MEK inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:61–68. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma L., Teruya-Feldstein J., Bonner P., Bernardi R., Franz D.N., Witte D., Cordon-Cardo C., Pandolfi P.P. Identification of S664 TSC2 phosphorylation as a marker for extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediated mTOR activation in tuberous sclerosis and human cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7106–7112. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu C.F., Liu Z.X., Cantley L.G. ERK negatively regulates the epidermal growth factor-mediated interaction of Gab1 and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19382–19388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozengurt E., Soares H.P., Sinnet-Smith J. Suppression of feedback loops mediated by PI3K/mTOR induces multiple overactivation of compensatory pathways: an unintended consequence leading to drug resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2477–2488. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caunt C.J., Sale M.J., Smith P.D., Cook S.J. MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitors and cancer therapy: the long and winding road. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:577–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markham A. Copanlisib: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2017;77:2057–2062. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0838-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mensah F.A., Blaize J.P., Bryan L.J. Spotlight on copanlisib and its potential in the treatment of relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: evidence to date. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:4817–4827. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S142264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolcher A.W., Sullivan R.J., Rasco D.W., Eroglu Z., Lakhani N., Kessler D., Usansky H., Reddy S., Denis L.J., Janku F. Phase 1 clinical safety and efficacy of ASN007, a novel oral ERK1/2 inhibitor, in patients with RAS, RAF or MEK mutant advanced solid tumors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019;18(12 Suppl.) TARG-19-PR09. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson C., Ye X., Pham T., Lin E., Chan S., McNamara E., Neve R.M., Belmont L., Koeppen H., Yauch R.L. AXL inhibition sensitizes mesenchymal cancer cells to antimitotic drugs. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5878–5890. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study. Kinome screening data generated for this study are summarized on Table S1.