Introduction

Extensive unemployment among autistic adults increases poverty and decreases independent living skills (Burgess & Cimera, 2014; Taylor et al., 2014); thereby reducing their overall quality of life. Over the next 10 years, approximately 800,000 autistic youth will exit high school and transition into adult roles (e.g., labor force) (Maenner et al., 2020; United States Census Bureau, 2019). Given the profound disparities in employment experienced by autistic transition-age youth (TAY) compared to their non-autistic peers and peers with other disabilities (Roux et al., 2015; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020), the field seeks to optimally position autistic TAY to live with higher levels of social and economic autonomy by ameliorating the challenges they face when securing employment (Baker-Ericzen et al., 2018).

Currently, transition services federally mandated by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) facilitate access to employment after high school for autistic TAY (IDEA, 2004). However, high schools have limited evidence-based practices to facilitate pre-employment transition services (Pre-ETS). For example, one such practice is Project SEARCH where autistic TAY learn independent living and job skills in classrooms and practice these skills during community-based internships collectively organized and managed by the public education system, state vocational rehabilitation services, and employers (Persch et al., 2015; Wehman et al., 2019). Although Project SEARCH and others (e.g., supported employment; Wehman et al., 2014) help shape Pre-ETS for autistic TAY, a critical gap in Pre-ETS is support to facilitate job interview skill development. Specifically, job interview skills are a critical barrier to employment among autistic TAY and adults (Lorenz et al., 2016; Sarrett, 2017), are identified by the United States Department of Education Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services as a critical Pre-ETS activity (United States Department of Education, 2017), and that a vast majority of employed autistic TAY receiving Pre-ETS supported by state vocational rehabilitation services completed job interviews prior to employment (Smith et al., in press).

Thus, several groups piloted the evaluation of various job interview training programs for autistic TAY and adults (Walker et al., 2019). Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT, a computerized job interview simulator) emerged with the strongest track record of efficacy across five randomized controlled trials (e.g., Smith, Fleming, Wright, Jordan, et al., 2015; Smith, Fleming, Wright, Roberts, et al., 2015; Smith, Bell, et al., 2016) and was found to help autistic young adults improve their job interview skills and interview self-efficacy in a laboratory setting (Smith, Ginger Wright, Wright, Taylor, et al., 2014), which was replicated in school settings (Arter et al., 2018; Ward & Esposito, 2018).

Given that VR-JIT was designed to meet the needs of adults with serious mental illness ( Smith, Ginger, Wright, Wright, Humm, et al., 2014) and had marginal translation to competitive employment among autistic young adults (Smith, Fleming, Wright, Losh, et al., 2015), VR-JIT was adapted, using community-engaged methods, to meet the needs of autistic TAY; and resulted in a new tool: Virtual Interview Training for Transition Age Youth (VIT-TAY) (Smith et al., 2020).

The current study used an intent-to-treat randomized controlled trial design to evaluate the initial feasibility and effectiveness of VIT-TAY among autistic TAY when implemented by teachers in high school settings. We hypothesized that teachers could feasibly deliver VIT-TAY; and that autistic TAY would have high treatment adherence and perceive VIT-TAY as highly acceptable. Based on prior VR-JIT research, we hypothesized that autistic VIT-TAY trainees receiving Pre-ETS, as compared to autistic TAY receiving Pre-ETS only, would demonstrate increased job interview skill, self-efficacy, and employment. Given that simulations are an exposure therapy (Meyerbröker & Emmelkamp, 2010) and that job interview anxiety disrupts job interview performance outcomes (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004), we hypothesized that VIT-TAY would reduce job interview anxiety. Lastly, we explored the correlates of VIT-TAY feasibility and effectiveness outcomes to inform a future validation trial.

Methods

Participants

Participants (ages 16 to 26), included 71 autistic TAY enrolled in high school Pre-ETS. Five school partners (three public, one private, one charter) were recruited through community outreach and conference presentations; and were located in urban, suburban, and rural communities. The research team led informational study presentations for families at the schools or school partners sent information about the study to families via internal listservs with directions to contact the research team. To meet the criteria of an autism diagnosis, participants needed a score of 60T or higher via parent or teacher report using the Social Responsiveness Scale (2nd Edition, SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012) or an autism eligibility via their educational record. SRS-2 internal consistency was strong (α=0.97).

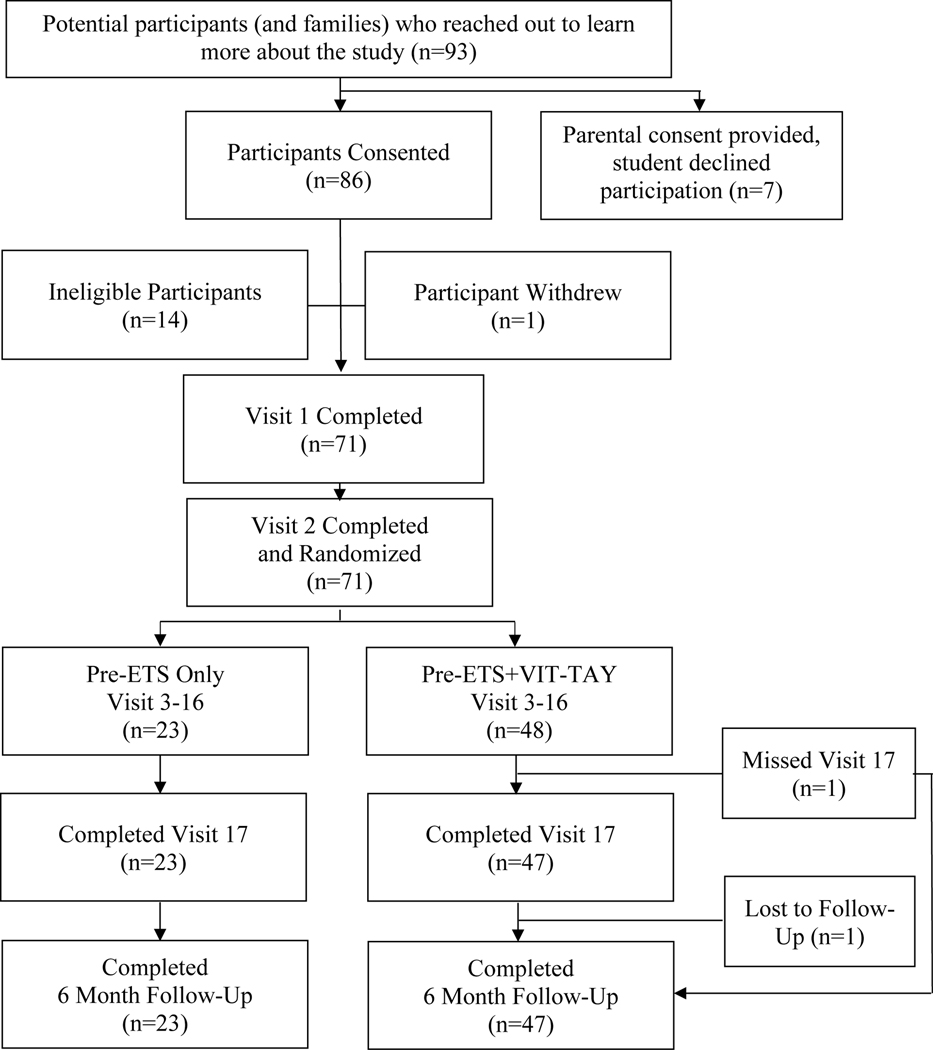

Additional inclusion criteria included: 1) at least a 3rd grade reading level; and 2) willingness to be video recorded. Participants were excluded if they had the following: 1) uncorrected hearing or visual limitations that prevented them from using VIT-TAY; and 2) a documented medical illness compromising their cognition (e.g., traumatic brain injury). The University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent (or assent with parental permission for minors). Participants were block randomized at a 2:1 ratio to a Pre-ETS with VIT-TAY group (Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY, n=48) or Pre-ETS only group (Pre-ETS only, n=23). The uneven randomization scheme enabled us to learn more about the intervention and implementation processes. See CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram of Study Design

Interventions

Pre-employment Transition Services.

Per their usual Pre-ETS, all five schools implemented work-based learning experiences (e.g., volunteering, job shadowing, trial work experiences) and workplace readiness training (e.g., communication skills, job seeking skills, soft skills). Three schools implemented evidence-based practices drawn from the National Technical Assistance Center on Transition (NTACT, 2020), the Workforce Innovation Technical Assistance Center (WINTAC, 2020), the Life Centered Education (Brolin, 1997), and the Practical Assessment Exploration System (Smith-Demers et al., 2017). One school implemented Project SEARCH (Wehman et al., 2019) and one school did not use a specific evidence-based practice. Students from three schools completed 1–3 mock interviews (approximately 5 minutes each) prior to study enrollment, while two schools completed no mock interviews between enrollment and post-test. See Supplemental Methods for additional details describing Pre-ETS.

Virtual Interview Training for Transition-Age Youth (VIT-TAY).

Developed by SIMmersion, LLC (www.simmersion.com), VIT-TAY provides trainees with an opportunity to repeatedly practice interviewing for a job at fictional company ‘Wondersmart’. Prior to interviewing, trainees review self-guided e-learning materials on how to find, prepare for, succeed in, and follow-up on job interviews that includes the review of 10 job interview skills (see below). Trainees also complete an online job application for one of 14 jobs (e.g., cashier, clerical, customer service, food services, inventory, janitorial, web developer) that informs the virtual interview experience.

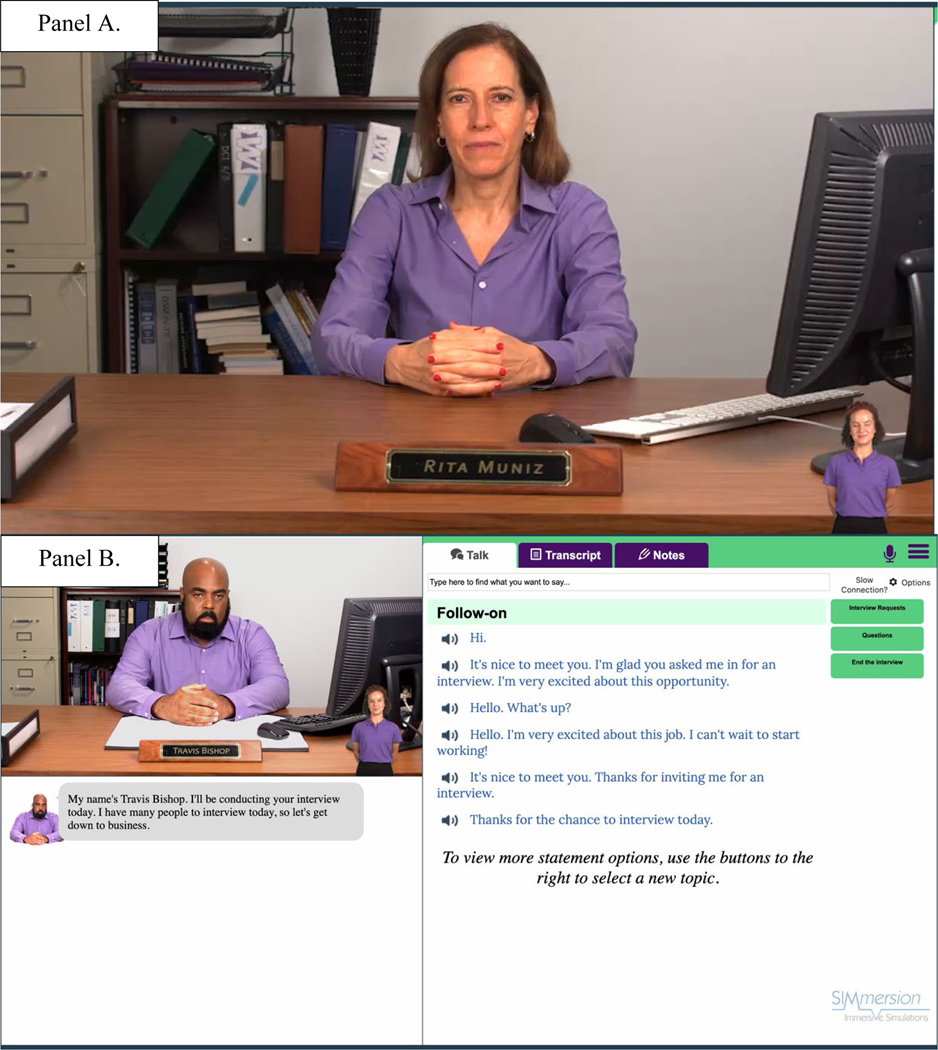

Then trainees enage in a computerized job interview simulator (delivered via the internet) that uses virtual interviewers featuring actors portraying Ms. Rita Muniz (Figure 2, Panel A, Full Screen Mode) and Mr. Travis Bishop (Panel B, Interface Mode). VIT-TAY adapted the overarching strategies of VR-JIT to target the learning needs of autistic TAY (Table 1). Specifically, VIT-TAY uses the same virtual job interview platform as VR-JIT, which allows trainees to watch video clips of the virtual interviewer and answer questions directly or redirect the conversation based on their needs (e.g., disclosing a disability).

Figure 2.

Virtual interviewers Ms. Rita Muniz (Panel A) and Mr. Travis Bishop (Panel B).

Table 1:

Virtual Interview Training for Transition Age Youth Features based on Virtual Reality Job Interview Training

| VR-JIT Features | VIT-TAY Features |

|---|---|

| Repeated practice with one virtual interviewer (Molly Porter, Caucasian female) | Repeated practice with two virtual interviewers (Rita Muniz, Latinx female; Travis Bishop, African American male) |

| Real-time feedback via non-verbal cues | Real-time feedback via non-verbal cues |

| Review of color-coded transcript with feedback on responses given to virtual interviewer targeted at an 8th grade reading level | Review of color-coded transcript with feedback on responses given to virtual interviewer targeted at a 4th grade reading level |

| An assessment of performance across key learning goals (10 items) at three levels of play (i.e., Easy, Medium, Hard) | Scaffolded assessment of performance across key learning goals at three levels of play (i.e., Easy = 4 goals, Medium = 7 goals, Hard = 10 goals) |

| Practice completing job applications with eight available jobs | Practice completing job applications with 14 available jobs |

| Didactic training on job interview preparation targeted at an 8th grade reading level | Multi-media training on job interview preparation targeted at a 4th grade reading level |

| Social storytelling with virtual co-worker, Kendra | |

| Token reward system |

Abbreviations. Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT); Virtual Interview Training for Transition-Age Youth (VIT-TAY).

Based on prior research evaluating scaffolding in autism (Kerr, Neale, & Cobb, 2002), VIT-TAY was designed to implement scaffolding across progressively more difficult interviews. Specifically, VIT-TAY has three difficulty levels (easy, medium, hard) and the transition between them is scaffolded. The ‘easy’ interviews target four job interview skills: 1) confidence; 2) positivity; 3) professionalism; and 4) interest in the job. These skills help answer the question “Are you someone they want to work with?” The medium interviews include the 4 easy job interview skills and add three additional skills: 5) honesty; 6) dependability; and 7) ability to work well with others. The new skills at medium answer the question “Will you be a good worker?” The hard interviews include the 7 job interview skills from ‘easy’ and ‘medium,’ and add three additional skills: 8) sharing strengths and skills; 9) sharing past experiences; and 10) sharing limitations. The new skills at hard answer the question “Will you do a good job?” The 10 targeted job interview skills were identified based on the job interview literature (Huffcutt, 2011), and the scaffolding decisions were determined by a community-engaged intervention development framework with autism stakeholders (Smith et al., 2020). See Supplemental Methods for examples of interview questions, successful responses, and feedback.

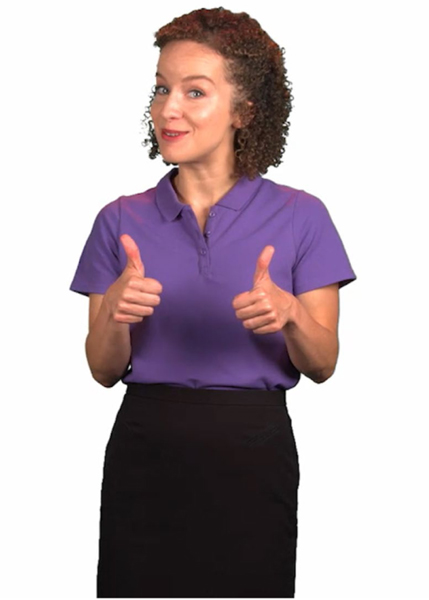

VIT-TAY also has four levels of feedback. The first level is an on-screen virtual help coach, Kendra (Figure 3), who provides real-time feedback throughout the interview via nonverbal cues to alert trainees to successful responses and mistakes. The second level is a color-coded transcript that provides feedback on why specific responses were successful or how they could be improved. At the third level, the VIT-TAY algorithm generates a score out of 100 points reflecting one’s performance on each of the 10 job interview skills. See Supplemental Methods for additional details describing VIT-TAY scoring. The fourth level is a performance assessment via video and text that qualitatively reviews each of the 10 job interview skills and the three questions reflecting easy, medium, and hard interviews. VIT-TAY also includes supplemental training materials to support the practice experience: 1) Kendra, a virtual job coach (Figure 3), is the center of a social story framework to guide the experience and provide optional voiceovers for all written content; and 2) a token reward system to boost the social storytelling framework (Smith et al., 2020). See Supplemental Methods for additional details describing supplemental training materials.

Figure 3.

Virtual job coach Kendra.

Study Procedures

After participants provided consent (or assent with parental permission), teachers or parents completed the SRS-2 and an educational record review to validate study inclusion. Both groups of participants completed pre-test and post-test assessments at their schools in private rooms. Pre-test assessments were completed during two visits (see Figure 1). During visit 1, the team reviewed the signed consent (or assent) with participants, completed an employment history interview, and a neuropsychological evaluation. During visit 2, participants completed a mood survey, a mock job interview (i.e., role-play), and a series of self-report measures. Participants were notified of their random assignment after completing visit 2. In parallel to visits 1 and 2, parents (or teachers if parents were non-responsive) completed a behavioral assessment for each participant. Post-test assessments were completed during a single visit where all participants completed a second mock job interview and the same self-report measures from pre-test visits. Additionally, Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY participants completed a self-report on VIT-TAY acceptability. A six-month follow-up was conducted with participants to obtain their employment outcomes. Participants were sent a reminder letter two weeks before their six-month follow-up date. If non-responsive via phone and email after 4 weeks, we obtained employment outcomes from parents (or teachers if parents were non-responsive). See Supplemental Methods for research staff and teacher training procedures.

VIT-TAY Implementation Procedures

Following the completion of pre-test assessments, teachers were asked to facilitate 15 sessions (approximately 45 minutes each) for participants using VIT-TAY. During sessions 1 and 2, participants received their individual account and password and then teachers oriented participants on how to login and use the e-learning curriculum within VIT-TAY. Next, participants learned about the ten job interview skills targeted by the intervention and reviewed parts of the curriculum that advised on other job interview processes (e.g., advice for how to dress for an interview).

During session 3, teachers oriented participants on completing the VIT-TAY job application and navigating the virtual interview interface (Figure 2, Panel B). During sessions 4 through 15, participants completed additional virtual interviews and re-engaged the e-learning curriculum as-needed. Teachers were instructed to help participants review their virtual interview transcript and the participant’s performance assessment. Based on prior research with VR-JIT (Smith, Fleming, Wright, Jordan, et al., 2015), the completion of at least 15 virtual interviews was recommended.

To promote hierarchical learning, participants were asked to progress through VIT-TAY’s three difficulty levels. First, if participants achieved a score of 90 or higher in the first three ‘easy’ interviews, they advanced to ‘medium’; if not, they had two more attempts to achieve 90 or higher. Students automatically advanced to ‘medium’ after five completed ‘easy’ interviews, regardless of score. Second, participants continued with three to five interviews on ‘medium’ using the same advancement progression to determine when they were ready for ‘hard.’ Participants were asked to perform ‘hard’ interviews for the remainder of their training.

Study Measures

Background Characteristics

Demographic and employment history.

Each participant completed a demographic and employment history survey during their baseline visit. Participants answered questions about their current and past employment and job interview history. This survey was adapted from prior research (Smith, Ginger Wright, Wright, Taylor, et al., 2014).

Depressive symptoms.

Participants self-reported state-level depressive symptoms at pre-test using the brief version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (b-MFQ; Angold et al., 1995); which was validated among autistic youth (Rai et al., 2018). The b-MFQ included 13 items evaluating feelings and behavior over the past two weeks. Participants responded on a scale of 0=“not true,” 1=“somewhat true,” and 2=“true” with scores of 12 or greater suggesting clinical depression. Internal consistency was strong (α=0.81).

Cognitive ability.

We assessed crystallized and fluid cognition using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Toolbox Cognition Battery (Akshoomoff et al., 2013; Weintraub et al., 2013). The battery included seven computerized tests requiring approximately 60 minutes to complete. Internal consistency for crystallized cognition (α=0.71) and fluid cognition were acceptable (α=0.70). Fully corrected T-scores reflected: 1) accumulation of knowledge and skills (i.e., crystallized cognition); and 2) ability to think logically and solve problems (i.e., fluid cognition). Additional details are in the Supplemental Methods.

Behavioral challenges.

We assessed behaviors as proxies for trait-based mental health challenges using parent/teacher-reports with the standardized child behavior checklist (CBCL) or adult behavior checklist (ABCL) (Achenbach, 1997; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The CBCL/ABCL rated 118 trait behaviors that reflect internalizing (i.e., anxious/depressed, somatic complaints, and withdrawn (ABCL) or withdrawn/depressed (CBCL)) and externalizing behaviors (i.e., rule-breaking behavior, aggressive behavior, and intrusive [assessed with ABCL only]). Internal consistency was acceptable across the three internalizing behavior items (α=0.71). Internal consistency was acceptable across the three externalizing behavior items among participants with ABCL data (n=46; α=0.78), and internal consistency was strong across the two externalizing behavior items among participants with CBCL data (n=23, α = 0.88). The behaviors are rated on a three-point scale of 0=“not true,” 1=“somewhat true,” and 2=“very true,” where higher total t-scores reflected more behaviors.

Acceptability and Adherence Outcomes

To assess VIT-TAY acceptability, we adapted the Treatment Acceptability Rating Form (Reimers & Wacker, 1988). The adapted form used a five-item self-report scale from 1=“not at all true” to 5=“very true”). Sample items included “Virtual interviewing was easy to do” and “Virtual interviewing was enjoyable.” Internal consistency was acceptable (α=0.82). To assess VIT-TAY adherence, we recorded the total number of completed virtual interviews, the frequency of participants who progressed from easy-to-medium-to-hard interviews and completed at least five hard interviews, and the total number of minutes engaged with virtual interviewers.

Effectiveness Outcomes

Job Interview Skills.

We assessed job interview skills at pre- and post-test visits via a single mock interview completed with a research team member using a version of the Mock Interview Rating Scale (MIRS; Smith, Ginger, Wright, Wright, Humm, et al., 2014) adapted for autism (i.e., A-MIRS). Prior to using the scale, coders were instructed to watch the video one time and then rate the participant’s ‘likeliness to be hired’ as a global rating of overall job interview skill (scaled from 1=“unlikely” to 5=“very likely”). Then, coders were asked to watch the video again and rate 11 job interview skill items (using a 7 point Likert-type scale): 1) confidence; 2) being positive; 3) professionalism; 4) showing interest; 5) honesty; 6) being dependable/hardworking; 7) working well with others; 8) sharing strengths and skills; 9) sharing past experiences; 10) sharing past limitations; and 11) overall rapport. A total score was computed by summing the 11 job interview skills. All coders were trained with four gold standard practice videos before independently coding study videos. Overall reliability was strong (ICC=0.97). Additionally, we randomly double coded approximately 25% of the videos to prevent drift where the coding trainer met with the coders to review and discuss coding inconsistencies (i.e., codes more than one point apart on a given domain) and reach a consensus score. Additional A-MIRS details are in the Supplemental Methods.

Job interview self-efficacy.

Participant’s self-reported their job interview self-efficacy after completing a mock job interview. This measure consisted of 11 items using a five-point Likert-type scale (1=“not at all true” to 5=“very true”), and we used a total score in our analyses. Sample items included: “I did a good job talking about my strengths” and “I did a good job talking about working with others.” Internal consistency was strong at pre-test (α=0.94) and post-test (α=0.93).

Job interview anxiety.

Each participant self-reported their anxiety about job interviewing via a modified version of the brief Personal Report of Public Speaking Apprehension (PRSPA; McCroskey, 1970). After reviewing the brief PRSPA, we selected and reframed 10 items using a three-point Likert-type scale (0=“not at all”, 1=“sometimes”, 2=“often”), and we used a total score in our analyses. Sample items included: “During the job interview role-play: My body felt tense” and “I was breathing faster than usual.” Participants completed the survey after their mock job interview so they could reflect on their experience during the role-play. Internal consistency was strong at pre-test (α=0.84) and post-test (α=0.81).

Vocational Outcomes.

At six-month follow-up, participants completed a brief vocational interview reflecting whether they obtained employment, an internship (paid or unpaid), or a volunteer position (individually coded as 1=“yes” and 0=“no”). Participants were asked to characterize employment as either 1) a competitive and integrated job in the community that was not set aside or obtained after completing an internship or volunteer position with that employer; 2) a job obtained after completing an internship or volunteer position with that employer; or 3) informal employment (i.e., cash under the table). Participants also self-reported whether they obtained a job (or completed a job interview) in the past six months (1=“yes” and 0= “no”) and how many weeks they actively searched for employment during the six-month follow-up.

Data Analysis

We evaluated the study variables for normality and found multiple variables were moderately-to-highly positively skewed (skewness ranging from 0.62 to 1.07) and moderately negatively skewed (skewness ranging from −0.53 to −0.95). The variables were transformed using a squared and square root approach (Box & Cox, 1964). In addition, pre-test and post-test job interview self-efficacy were found to be kurtotic.

Acceptability and adherence.

We evaluated the acceptability (i.e., total score on acceptability measure) and adherence (i.e., total completed virtual interviews, total number of minutes engaged with virtual interviews, frequency of participants who completed the progression from easy-to-medium-to-hard) to VIT-TAY with descriptive statistics.

Sample characterization.

We used T-tests and chi-square analyses to evaluate the presence of between-group differences at pre-test related to background characteristics.

Effectiveness Outcomes.

We conducted repeated measures analysis of variance to evaluate whether VIT-TAY was associated with changes (between pre-test and post-test) in job interview skill, self-efficacy, and anxiety. Specifically, we examined whether there was a significant group-by-time interaction effect. Additionally, we generated partial eta-squared (ηp2) values to characterize the group-by-time effect sizes. Given that many autistic TAY also have other emotional/behavioral disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression) that interfere with their learning and behavioral development (Clinton, 2016; Georgiades et al., 2011), we evaluated the presence of a co-occurring emotional disability as a covariate in our analyses.

For vocational outcomes, we first used chi-square analyses to evaluate whether VIT-TAY training was associated with a higher rate of attending a job interview or obtaining competitive and integrated employment by 6-month follow-up. Second, we conducted a Firth logistic regression (Firth, 1993) to evaluate the aforementioned relationship while covarying for baseline employment status. We also used chi-square analyses to evaluate between-group differences with respect to obtaining non-competitive employment or any vocational outcome (i.e., employment [any type], internship, or volunteering). We used a t-test to evaluate whether the Pre-ETS only and Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY groups differed with respect to the number of weeks they searched for a job. Given the established efficacy of the original VR-JIT (e.g., Smith, Fleming, Wright, Jordan, et al., 2015; Smith, Fleming, Wright, Roberts, et al., 2015; Smith, Bell, et al., 2016) and that job interview anxiety has been treated via supportive technology (Rockawin et al., 2012), we conducted these analyses using one-tailed tests.

Exploratory Correlations.

Using Spearman’s rho (ρ), we first explored whether the VIT-TAY acceptability, adherence, and performance variables were correlated with the effectiveness outcomes. Second, we explored whether VIT-TAY adherence and performance variables were correlated with VIT-TAY acceptability. Third, we explored whether clinical, cognitive, and behavioral variables were correlated with VIT-TAY acceptability, adherence, and performance. Fourth, we explored whether the clinical, cognitive, and behavioral variables were correlated with effectiveness outcomes. Lastly, we explored whether post-test job interview skill, interview self-efficacy, and job interview anxiety were correlated with the employment outcomes. All correlations used two-tailed tests.

Missing Data.

Consistent with the intent-to-treat randomized controlled trial design, we used the expectation-maximization algorithm for data missing completely at random (Dempster et al., 1977) to conduct data imputation via the SPSS missing values analysis package. This maximum likelihood estimation method generates unbiased estimates and provides less biased parameter estimates as compared to regression or mean imputation (Schafer & Graham, 2002). We evaluated our analyses with and without the imputed data. The magnitude and direction of the effects did not differ. Thus, we proceeded with analyses using the full sample with imputed data to optimize power. Additional details regarding imputed variables can be found in Supplemental Methods.

Community Involvement

Members of the autism community were not involved in the development of research questions, outcome measures, study design, or implementation of this trial.

Results

Acceptability and Adherence

Participants reported VIT-TAY as highly acceptable with m=20.36 (sd=4.21; range 7 to 25). With respect to adherence, participants completed m=15.65 (sd=5.06; range 4 to 30) virtual interviews and spent m=211.30 (sd=79.95; range 41 to 422) minutes engaging with the virtual interviewers. Also, participants completed m=4.37 (sd=1.65; range 3 to 10) virtual interviews on ‘easy,’ m=4.87 (sd=1.69; range 1 to 9) virtual interviews on ‘medium,’ and m=6.41 (sd=5.01; range 0 to 20) virtual interviews on ‘hard.’ Overall, their means score across all virtual interviews was m=72.55 (sd=13.07).

We observed that 28 of 46 (60.8%) participants successfully progressed through the recommended easy-to-medium-to-hard difficulty levels on the virtual interviews (including the completion of five hard interviews). In addition, n=3 participants (6.5%) completed four hard interviews and n=5 participants (10.9%) completed three hard interviews, while n=3 participants (6.5%) completed one or two hard interviews. Also, n=6 participants (13.6%) completed no hard interviews but completed the progression through medium. Lastly, n=1 participant failed to complete the progression through medium. Of note, n=2 participants mistakenly used each other’s ‘saved’ password on their computer. We were not able to accurately determine how many trials or minutes of interviewing they completed.

Background Characteristics

Our between-group analyses revealed that the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY and Pre-ETS only groups did not statistically differ with respect to age, race, gender, and remaining demographic and background characteristics (Table 2), with the exception that the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group trended towards greater internalizing behavioral challenges than the Pre-ETS only group (p=0.08).

Table 2.

Background Characteristics of Study Sample

| Pre-ETS only (n=23) | Pre-ETS +VIT-TAY (n=48) | Test Statistic (T or X2) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 19.4 (2.6) | 19.8 (3.0) | 0.6 | 0.53 |

| Biological sex (% male) | 87.0% | 79.2% | 0.4 | 0.43 |

| Social Responsivity Scale (2nd Edition; M, SD) | 63.9 (14.1) | 65.7 (13.2) | 0.5 | 0.60 |

| Race (%) Caucasian Black/African American Latinx More than one race Asian American Native American |

56.5% 34.8% 0.0% 8.7% 0.0% 0.0% |

54.2% 22.9% 12.5% 4.2% 4.2% 2.1% |

5.7 | 0.34 |

| Current grade (%) Sophomore Junior Senior Transitional year |

8.7% 13.0% 26.1% 52.2% |

6.3% 12.5% 29.1% 52.1% |

0.2 | 0.98 |

| Co-occurring IDEA categorizations (%) | ||||

| Other health impairment | 21.7% | 20.8% | <0.1 | 0.93 |

| Specific learning disability | 13.0% | 10.4% | 0.1 | 0.74 |

| Cognitive impairment | 8.7% | 18.8% | 1.2 | 0.27 |

| Emotional disturbance | 13.0% | 10.4% | 0.1 | 0.74 |

| Cognitive ability (M, SD) | ||||

| Fluid cognition | 33.3 (13.1) | 29.6 (10.9) | -1.3 | 0.20 |

| Crystallized cognition | 40.1 (11.5) | 42.7 (12.4) | 0.8 | 0.40 |

| Highest parental education level (%) | ||||

| High school graduate (or equivalent) or less Some college Associate degree (or equivalent) Undergraduate degree Graduate degree |

6.7% 20.0% 6.7% 40.0% 26.7% |

3.8% 26.9% 11.5% 30.8% 26.9% |

0.8 | 0.94 |

| Mental health (M, SD) | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 4.7 (4.1) | 5.7 (4.1) | 0.9 | 0.33 |

| Internalizing behaviors | 54.9 (10.1) | 59.5 (10.3) | 1.8+ | 0.08 |

| Externalizing behaviors | 51.6 (11.0) | 52.0 (10.3) | 0.1 | 0.89 |

| Vocational history (%) | ||||

| Ever had a job interview | 34.8% | 29.2% | 0.2 | 0.63 |

| Ever employed at competitive, integrated job | 21.7% | 33.3% | 1.0 | 0.32 |

| Interviewed for this job | 60.0% | 20.0% | 2.9 | 0.09 |

| Currently employed at competitive, integrated job | 4.3% | 10.4% | 0.7 | 0.39 |

| Interviewed for this job | 100% | 20% | 2.4 | 0.12 |

| Job search projection Currently or within 6 months Beyond 6 months (or don’t know) |

69.6% 30.4% |

50.0% 50.0% |

2.4 | 0.12 |

| Currently in an internship (paid or unpaid) | 17.4% | 12.5% | 0.3 | 0.58 |

| Currently in a volunteer positition | 30.4% | 33.3% | 0.1 | 0.81 |

Abbreviations. Special eduation pre-employment transition services as usual (Pre-ETS); Virtual Interview Training for Transition-Age Youth (VIT-TAY); Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) M (mean); SD (standard deviation).

Effectiveness Outcomes

Job Interview Skill Outcomes.

The effectiveness outcome results are displayed in Table 3. Based on prior research (Clinton, 2016; Georgiades et al., 2011), we evaluated a co-occurring emotional disability as a fixed effect covariate. However, the time-by-emotional disability interaction was non-significant (p>0.90), and we removed it from the models. Based on trend-level between-group differences with respect to internalizing behavior (Table 2), we included internalizing behavior as a covariate. The time-by-internalizing behavior covariates explained a trend level of variation (p<0.10) in the outcomes and was included in the final models.

Table 3.

Estimated Means (Standard Error) for Effectiveness Outcomes

| Effectiveness Outcomes | Pre-ETS only Group | Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY Group | F- Test |

η p2 Effect Size |

P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test mean (SE) | Post-test mean (SE) | Pre-test mean (SE) | Post-test mean (SE) | ||||

| Likeliness to be Hired (Global Rating) | 2.9 (0.3) | 2.6 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.2) | 7.4 | 0.10 | 0.004 |

| Mock Interview Total Score | 45.9 (1.9) | 43.6 (1.9) | 46.8 (1.3) | 49.6 (1.3) | 12.4 | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Are you someone they want to work with? | 16.7 (0.8) | 15.2 (0.8) | 16.5 (0.5) | 17.5 (0.5) | 16.2 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Confidence | 4.3 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.2) | 11.4 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Positivity | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.9 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.1) | 4.7 (0.1) | 6.8 | 0.09 | 0.006 |

| Professionalism | 4.9 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.9 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.2) | 8.9 | 0.12 | 0.002 |

| Interested in position | 3.5 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.2) | 3.8 (0.2) | 3.5 (0.1) | 0.3 | <0.01 | 0.294 |

| Will you do a good job? | 12.7 (0.5) | 12.9 (0.6) | 13.4 (0.4) | 14.5 (0.4) | 2.9 | 0.04 | 0.046 |

| Honesty | 5.2 (0.2) | 5.1 (0.2) | 5.1 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.2) | 2.4 | 0.03 | 0.063 |

| Dependability | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.2) | 1.3 | 0.03 | 0.134 |

| Working well with others | 3.3 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.2) | 3.9 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.2) | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.275 |

| Will you be a good worker? | 12.6 (0.6) | 11.5 (0.6) | 12.3 (0.4) | 13.0 (0.4) | 8.1 | 0.11 | 0.003 |

| Sharing strengths and skills | 4.3 (0.3) | 3.9 (0.2) | 4.3 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.2) | 5.3 | 0.07 | 0.013 |

| Sharing past experiences | 4.1 (0.3) | 3.9 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.2) | 2.2 | 0.03 | 0.071 |

| Sharing limitations | 4.2 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.1) | 4.3 | 0.06 | 0.021 |

| Overall Rapport | 3.9 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.2) | 0.1 | <0.01 | 0.408 |

| Job interview self-efficacy* | 45.9 (3.4) | 44.3 (3.1) | 47.2 (2.6) | 43.5 (2.4) | 0.9 | 0.01 | 0.358 |

| Job interview anxiety* | 5.0 (4.7) | 4.4 (4.4) | 7.0 (4.1) | 5.7 (3.8) | 3.7 | 0.053 | 0.029 |

Unadjusted mean and standard deviations are reported for interpretability.

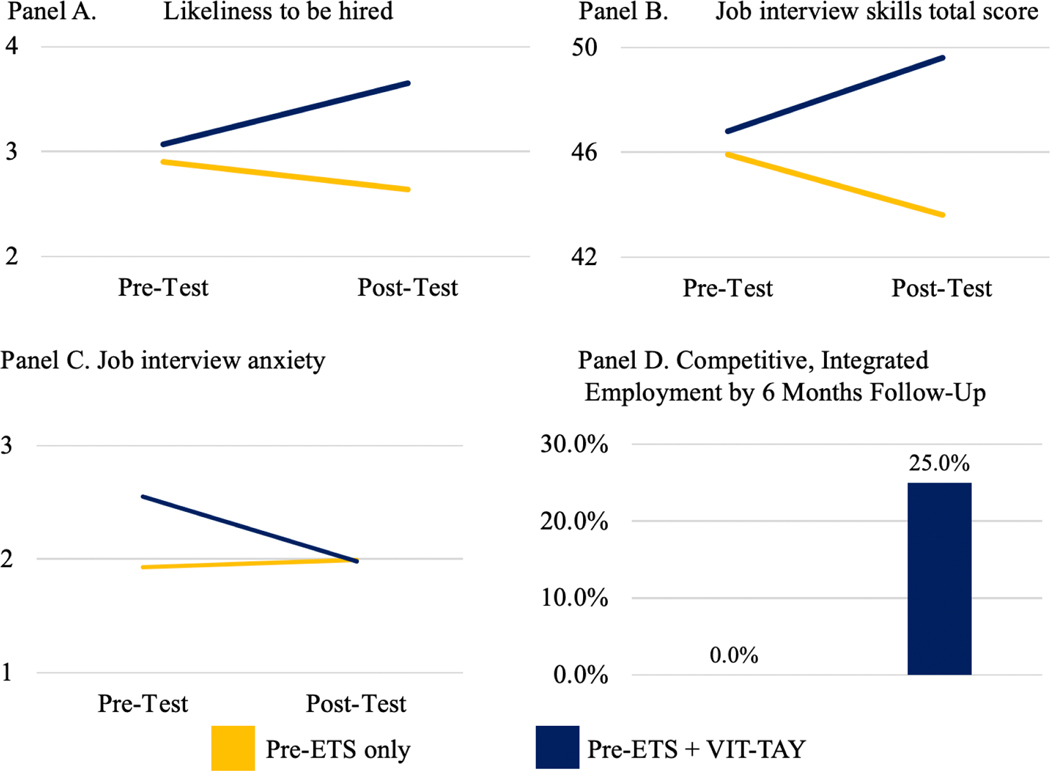

A significant group-by-time interaction was found for the global rating of ‘likeliness to be hired’ (F1,68=7.4, p<0.01) where Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY were rated as having a greater likeliness of being hired between pre-test and post-test compared Pre-ETS only (effect size ηp2=0.10 [Figure 4. Panel A]). We observed a significant group-by-time interaction when evaluating the job interview skills total score (F1,68=12.4, p<0.001), where Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY were rated as having improved overall job interview skills between pre-test and post-test as compared to Pre-ETS only (effect size ηp2=0.15. [Figure 4. Panel B]).

Figure 4.

Selected Effectiveness Outcomes. This figure plots the significant group-by-time interactions for Likeliness to be hired (Panel A), Job interview skills total score (Panel B), and Job Interview Anxiety (Panel C); and displays the significant gap in employment between groups at six-month follow-up (Panel D). Abbreviation: Pre-ETS; special education pre-employment transition services.

The A-MIRS provided ratings on 10 individual job skill targets embedded within the ‘easy’ (“Are you someone they want to work with?”); ‘medium’ (“Will you do a good job?”); and ‘hard’ (“Are you a good worker?”) levels of difficulty. With respect to the ‘easy’ level of difficulty (Table 3), we observed a significant group-by-time interaction where the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group, compared to Pre-ETS only, significantly improved being rated as “Are you someone they want to work with?” (F1,68=16.2, p<0.001; ηp2=0.20). The ‘easy’ level job interview skills (i.e., confidence, positivity, professionalism) had significant group-by-time interactions (all p<0.05; all ηp2>0.09); while ‘interested in the position’ did not have a significant group-by-time interaction (p>0.10).

For ‘medium’ level of difficulty (Table 3), we observed a significant group-by-time interaction where Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY, compared to Pre-ETS only, improved being rated as “Will you do a good job?” (F1,68=2.9, p<0.05; ηp2=0.04). The ‘medium’ level job interview skills (i.e., honesty, dependability, working well with others) had non-significant group-by-time interactions (all p>0.05).

For ‘hard’ level of difficulty (Table 3), we observed a significant group-by-time interaction where Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY, compared to Pre-ETS only, improved their rating “Will you be a good worker?” (F1,68=8.1, p<0.01; ηp2=0.11). The ‘hard’ level job interview skills (i.e., sharing strengths and skills, sharing limitations) had significant group-by-time interactions (both p<0.05; ηp2>0.05). However, the ‘hard’ level skill ‘sharing past experiences’ had a trend group-by-time interaction (p=0.071).

Job Interview Anxiety.

We observed a significant group-by-time interaction for job interview anxiety where Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY had reduced job interview anxiety between pre-test and post-test compared to Pre-ETS only group (F1,68=3.7, p<0.05; ηp2=0.053) [Figure 4. Panel C]. We also observed a group-by-time-by-emotional disability interaction (F1,68=3.4, p<0.05; ηp2=0.049. The finding suggested Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY with co-occurring emotional disabilities had a greater reduction in job interview anxiety than Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY without co-occurring emotional disabilities. We did not observe a significant group-by-time interaction when evaluating job interview self-efficacy (p>0.30).

Employment Outcomes.

We observed that Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY had a higher proportion of competitive and integrated employment when compared to Pre-ETS only (25.0% vs. 0.0%, χ2 =6.9, p<0.01 [Figure 4. Panel D]). Moreover, the Firth logistic regression (Waldχ2=8.6, p<0.05) confirmed the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group was more likely to obtain employment than the Pre-ETS group (OR=16.0; p<0.05; 95% CI 1.35, 189.17) after covarying for baseline employment (OR=12.4; p<0.01; 95% CI 2.39, 64.06). We also observed that Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY had a higher proportion of any employment type when compared to Pre-ETS only, but this difference did not attain statistical significance (41.7% vs. 30.4%, χ2=0.8, p=0.18; OR=1.53, CI=0.62, 3.75, p=0.22 [after covarying for baseline employment]). In addition, the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY and Pre-ETS only groups did not differ (χ2=0.1, p=0.76) with respect to the proportion of students who attended job interviews during the six-month follow-up (25.0% vs. 21.7%, respectively). Also, Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY (M=1.7 weeks, SD=2.7) spent more time job searching after post-test compared to Pre-ETS only (M=0.8 weeks, SD=1.3; T=2.01, p<0.05). See Supplemental Table 1 for vocational outcomes related to internships, volunteer work, and Supplemental Results for findings on job seeking status.

Exploratory correlations within Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group

VIT-TAY acceptability, adherence, and performance variables were correlated with several effectiveness outcomes (Supplemental Table 2). Of note, the mean virtual interview performance score (across all trials) was correlated with the post-test role-play ratings: “likeliness to be hired” (ρ=0.36, p<0.05), the job interview total score (ρ=0.39, p<0.01), and several individual job interview skills. VIT-TAY acceptability, adherence, and performance variables were correlated with several demographic, clinical, cognitive, and behavioral variables (Supplemental Table 3). Of note, the mean virtual interview performance score was correlated with fluid cognition (ρ=0.47, p=0.001) and crystallized cognition (ρ=0.66, p<0.001). Demographic, clinical, cognitive, and behavioral sample characteristics were correlated with several effectiveness outcomes (Supplemental Table 4). Of note, autistic social challenges were negatively correlated with the job interview skill total score (ρ=−0.43, p<0.01) and several individual job interview skills. Among the effectiveness outcomes, we observed that the post-test ‘likeliness to be hired’ and job interview total scores were correlated with competitive employment (ρ=0.29, p=0.049; ρ=0.37, p=0.01; respectively) and having interviewed for a job (ρ=0.38, p=0.009; ρ=0.30, p<0.05; respectively) by six month follow-up. Post-test job interview anxiety was not correlated with any job interview skill measures or employment outcomes (all p>0.10).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the initial feasibility and effectiveness of VIT-TAY, which is a comprehensive simulator with a virtual interviewer adapted to meet the needs of autistic TAY and delivered via the internet. Our results revealed that VIT-TAY may be feasibly implemented as autistic TAY found VIT-TAY acceptable and successfully adhered to the training curriculum when delivered across five high schools that included public, private, and charter schools in rural, suburban, and urban communities. Moreover, the results suggest VIT-TAY may be promising as it translated into significant improvements in job interviewing ability, reduced job interview anxiety, and higher competitive employment rates.

This study also has several critical implications that will inform a fully powered validation trial of VIT-TAY within school-based Pre-ETS. Despite 48.6% of the sample being characterized as having moderate-to-severe autism and below average crystallized and fluid cognition (43.7% and 78.9% of sample at least two SD below national mean, respectively), participants were highly engaged using VIT-TAY, as evidenced by their completion of more than 15 virtual interviews, 3.5 hours of interactions with the virtual hiring manager, and approximately 78% of VIT-TAY trainees completing at least three hard interviews (after progressing through easy and medium interviews). Overall, a strong mean acceptability score of 20.36 (total possible score = 25) and the observed adherence to the VIT-TAY training protocol (implemented by teachers) confirms the feasibility of implementing (and evaluating) VIT-TAY in a school setting. Importantly, intervention acceptability is critical for an intervention’s effectiveness (Elliott, 2017), and the observed correlations between VIT-TAY acceptability and job interview skills at post-test support this prior work.

The effectiveness results have important implications for autistic TAY and the federally mandated Pre-ETS they receive at their schools. We observed that the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group had significant improvements in their overall job interview skills between pre-test and post-test when compared to the Pre-ETS only group. Improvements were largely in confidence, positively framing experiences, demonstrating professionalism, sharing strengths and skills, and sharing limitations. Moreover, we observed the same pattern of results in a global rating of the participant’s likeliness to be hired, which accounts for the nuances of a job interview not captured by the rating scale. Thus, this study provides initial evidence that the implementation of VIT-TAY within Pre-ETS could fill a critical gap in evidence-based services needed to help prepare autistic TAY enter the job market.

We also observed that Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY self-reported reduced job interview anxiety beyond Pre-ETS only. Given that the current study was not a fully-powered trial, this finding speaks to VIT-TAY’s potential as an effective exposure therapy given job interviewing is anxiety-provoking for many (McCarthy & Goffin, 2004), and especially for autistic TAY and adults who are vulnerable to anxiety (Joyce et al., 2017; Sarrett, 2017). We did not observe a significant group-by-time interaction with respect to job interview self-efficacy, which is not consistent with prior studies of virtual interview training with autistic youth (Arter et al., 2018; Ward & Esposito, 2018). This finding could reflect that with increasing job interview practice, autistic youth may become more aware of weaknesses in their job interviewing ability or the observed results could reflect a regression to the mean after a heightened initial self-report. Additionally, our assessment of self-efficacy may be limited as we collected the measure after the role-play was completed given few participants had previously completed a job interview.

With respect to translating VIT-TAY into real-world outcomes, the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group was significantly more likely to obtain a competitive and integrated job when compared to Pre-ETS only (25.0% vs. 0.0% and OR=15.98). These findings are consistent with prior research among individuals using virtual interviewing tools to enhance their job interview skills (Smith, Fleming, Wright, Jordan, et al., 2015). In addition, we found that 16.7% of the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group transitioned from internships or volunteering into jobs at those locations (i.e., non-competitive employment), which reflected that, overall, 41.7% of this group obtained employment. In comparison, 30.4% of the Pre-ETS only group obtained non-competitive employment. Although this between-group difference in total employment (competitive and non-competitive) didn’t obtain significance (OR=1.53, p=0.22), we can use this information to power future studies. Moreover, VIT-TAY performance was correlated with post-test job interview skill, which was subsequently correlated with obtaining competitive employment by six-month follow-up. Thus, our initial evidence suggests that VIT-TAY implemented within Pre-ETS may be an effective intervention for enhancing access to employment and the mechanism may be that VIT-TAY directly enhances job interview skills, which helps facilitate access to employment—a mechanism consistent with Smith et al., 2017. However, this model must be evaluated in future research.

We also learned from the supplmental results that job seeking autistic youth who practiced with VIT-TAY had approximaely double the employment rate as non-job-seekers (33.3% vs. 16.7%; OR=2.5, CI= 0.79, 7.88, p=0.09). Similarly, we observed that non-job-seeking autistic TAY randomized to the Pre-ETS+VIT-TAY group had a higher rate of attaining vocational outcomes of all types (jobs, internships, or volunteer positions) compared to non-job-seeking autistic TAY randomized to Pre-ETS only (83.3% vs. 57.1%; OR=3.8, CI= 0.80, 17.60, p=0.08). Although these differences did not attain significance and were likely underpowered, they suggest the benefits of VIT-TAY could be facilitating access to vocational outcomes beyond employment to include internships and volunteer work. As such, these findings need to be evaluated more deeply in a fully-powered trial given that internships and volunteering are critical vocational outcomes among transition age autistic youth (Test et al., 2009).

Limitations

Our results should be considered within the context of its limitations. First, this study was not fully powered to determine the effectiveness of the intervention; however, the observed initial effects can be used to design a fully-powered trial. Second, we intentionally recruited participants from public, charter, and private schools set in rural, urban, and suburban communities, which is a strength regarding studying feasibility. However, this approach limits the variation captured by these settings as a larger trial with multiple school partners in each of these communities is needed to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Third, although we emphasized recruitment from underrepresented minority groups, the study cannot generalize the outcomes to these groups individually. Fourth, the observed reduction in job interview anxiety could reflect a statistical regression to the mean. Fifth, three of five schools conducted mock interviews with students prior to, but not during, study enrollment. Thus, these procedures may have influenced the pre-test mock job interview performance. Meanwhile, the remaining two schools did not conduct mock interviews prior to or during study enrollment. Thus, our study protocol, though flexible, did not capture the potential impact of the usual ‘mock job interview training’ administered within services-as-usual.

Future Directions

Although the current study provides an in-depth analysis of the potential effectiveness of VIT-TAY, future studies are needed to evaluate the tool in several areas. First, a fully-powered study is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of VIT-TAY and among underrepresented minority groups. Second, the heterogeneity of autism is a critical consideration for future research. We found initial evidence that greater social challenges were related to poorer interview skills at post-test. However, we did not observe that social challenges were related to VIT-TAY acceptability, adherence, or performance. Moreover, we observed that greater crystallized cognition was related to stronger interview skills and VIT-TAY performance (but not adherence). Thus, future research must consider whether the effects of VIT-TAY are moderated by social challenges and crystallized cognition. Lastly, further studies may evaluate the implementation of VIT-TAY within Pre-ETS; particularly, focusing on organizational factors affecting implementation in schools (Damschroder et al., 2009; Owens et al., 2014).

Conclusion

This initial feasibility and effectiveness study suggests autistic TAY found VIT-TAY acceptable and adhered to the training. Moreover, the results revealed that autistic TAY who engaged in VIT-TAY within special education Pre-ETS significantly enhanced their interview skills, reduced interview anxiety, and had greater competitive employment within six months compared to autistic TAY receiving special education Pre-ETS without VIT-TAY. The observed job interview skill development and increased employment are critical as they are both nationally recognized service targets by the United States Department of Education Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services. An initial evaluation of VIT-TAY’s implementation strategies is ongoing and will lend additional insight into developing hypotheses for a large-scale validation trial of VIT-TAY within special education Pre-ETS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge that this study was supported by a grant to Dr. Matthew J. Smith from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH111531). We would like to acknowledge our participants for their time completing the study and our school partners for allowing us onsite to work with their students and teachers, including the following: Ann Arbor Academy, Plainfield, MI; Autism Model School, Toledo, OH; Lincoln Park High School, Lincoln Park, MI; South Field High School, South Field, MI; Troy High School, Troy, MI.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The University of Michigan will receive royalties from SIMmersion LLC on the sales of the virtual interview training tool that was the focus of this randomized controlled trial. These royalties will be shared with Dr. Matthew Smith and the University of Michigan School of Social Work. Dr. Smith adhered to the University of Michigan’s Conflict Management Plan that was reviewed and approved by a University of Michigan Conflict of Interest Committee. This manuscript includes authorship by Mr. Elkins, Ms. Humm, and Dr. Steacy who are paid employees of SIMmersion and own stock in the company. However, Mr. Elkins, Ms. Humm, and Dr. Steacy were not involved in the study’s design or administration. Moreover, there were not involved in the collection, management, or analysis of study data. Their authorship contributions were focused on the description of the intervention.

References

- Achenbach TM (1997). Manual for young adult self-report and young adult behavior checklist: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Akshoomoff N, Beaumont JL, Bauer PJ, Dikmen SS, Gershon RC, Mungas D, Slotkin J, Tulsky D, Weintraub S, Zelazo PD, & Heaton RK (2013). VIII. NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (CB): composite scores of crystallized, fluid, and overall cognition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev, 78(4), 119–132. 10.1111/mono.12038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, & Pickles A. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Arter P, Brown T, Law M, Barna J, Fruehan A, & Fidiam R. (2018). Virtual reality: improving interviewing skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Paper presented at the Proceedings of Societal for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzen MJ, Brookman-Frazee L, & Brodkin ES (2018). Accelerating research on treatment and services for transition age youth and adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 22(1), 2–5. 10.1177/1362361317738646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, & Cox DR (1964). An Analysis of Transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 26(2), 211–252. www.jstor.org/stable/2984418 [Google Scholar]

- Brolin DE (1997). Life centered career education: a competency based approach (Fifth Edition ed.). Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020). Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics 2019. (USDL-19–0326). Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Burgess S, & Cimera RE (2014). Employment outcomes of transition-aged adults with autism spectrum disorders: a state of the States report. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 119(1), 64–83. 10.1352/1944-7558-119.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton E. (2016). Comorbidity of autism spectrum disorders and emotional/behavioral disorders: Towards improved diagnostic procedures, instructional programming, and personnel preparation. Journal on Educational Psychology, 9(4), 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, & Gruber CP (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) (Second ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Corbiere M, Zaniboni S, Lecomte T, Bond G, Gilles PY, Lesage A, & Goldner E. (2011). Job acquisition for people with severe mental illness enrolled in supported employment programs: a theoretically grounded empirical study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 21(3), 342–354. 10.1007/s10926-011-9315-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A, Laird N, & Rubin DB (1977). Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 39(1), 1–38. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1977.tb01600.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SN (2017). The social validity of “Acceptability of behavioral interventions used in classrooms”: inferences from longitudinal evidence. Behavioral Disorders, 43(1), 269–273. 10.1177/0198742917739021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firth D. (1993). Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika, 80(1), 27–38. 10.1093/biomet/80.1.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades S, Szatmari P, Duku E, Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson S, Roberts W, Fombonne E, Mirenda P, Smith I, Vaillancourt T, Volden J, Waddell C, Thompson A, & Pathways in ASD Study Team. (2011). Phenotypic overlap between core diagnostic features and emotional/behavioral problems in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 41(10), 1321–1329. 10.1007/s10803-010-1158-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffcutt AI (2011). An empirical review of the employment interview construct literature. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 19(1), 62–81. 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2010.00535.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400, Pub. L. No. PL 101–476 (2004). Joyce C, Honey E, Leekam SR, Barrett SL, & Rodgers J. (2017). Anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty and restricted and repetitive behaviour: insights directly from young people with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(12), 3789–3802. 10.1007/s10803-017-3027-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr SJ, Neale HR, & Cobb SVG (2002). Virtual environments for social skills training: the importance of scaffolding in practice Proceedings of the fifth international ACM conference on Assistive technologies, Edinburgh, Scotland. 10.1145/638249.638269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz T, Frischling C, Cuadros R, & Heinitz K. (2016). Autism and overcoming job barriers: comparing job-related barriers and possible solutions in and outside of autism-specific employment. PLOS One, 11(1), e0147040. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner M, Shaw K, Baio J, Washington A, Patrick M, DiRienzo M, Christensen DL, Wiggins LD, Pettygrove S, Andrews JG, Lopez M, Hudson A, Baroud T, Schwenk Y, White Y, Robinson Rosenberg C, Lee L, Harrington RA, Huston M, Dietz PM (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 201. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 69(SS-4), 1–12. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J, & Goffin R. (2004). Measuring job interview anxiety: beyond weak knees and sweaty palms. Personnel Psychology, 57(3), 607–637. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.00002.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey JC (1970). Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Speech Monographs, 37, 269–277. 10.1080/03637757009375677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerbröker K and Emmelkamp PM (2010), Virtual reality exposure therapy in anxiety disorders: a systematic review of process-and-outcome studies. Depress. Anxiety, 27: 933–944. doi: 10.1002/da.20734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Technical Assistance Center on Transition (NTACT; 2020). National Technical Assistance Center on Transition: Effective Practices. https://transitionta.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Lyon AR, Brandt NE, Warner CM, Nadeem E, Spiel C, & Wagner M. (2014). Implementation science in school mental health: key constructs in a developing research agenda. School mental health, 6(2), 99–111. 10.1007/s12310-013-9115-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persch AC, Clearly DS, Rutkowski S, Malone HI, Darragh AR, & Case-Smith JD (2015). Current practices in job matching: A Project SEARCH perspective on transition. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 43(3), 259–273. 10.3233/JVR-150774 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rai D, Culpin I, Heuvelman H, Magnusson CMK, Carpenter P, Jones HJ, Emond AM, Zammit S, Golding J, Pearson RM (2018). Association of autistic traits with depression from childhood to age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 835–843. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers TM, & Wacker DP (1988). Parents’ ratings of the acceptability of behavioral treatment recommendations made in an outpatient clinic: a preliminary analysis of the influence of treatment effectiveness. Behavioral Disorders, 14(1), 7–15. 10.1177/019874298801400104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockawin D. (2012). Using innovative technology to overcome job interview anxiety. Australian Journal of Career Development, 21(2), 46–52. 10.1177/103841621202100206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Rast JE, Rava JA, & Anderson KA (2015). National autism indicators report: Transition into young adulthood. AJ Drexel Autism Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrett JC (2017). Interviews, disclosures, and misperceptions: autistic adults’ perspectives on employment related challenges. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(2). 10.18061/dsq.v37i2.5524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Bell MD, Wright MA, Humm L, Olsen D, & Fleming MF (2016). Virtual reality job interview training and 6-month employment outcomes for individuals with substance use disorders seeking employment. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 44, 323–332. 10.3233/JVR-160802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Fleming MF, Wright MA, Jordan N, Humm LB, Olsen D, & Bell MD (2015). Job Offers to Individuals With Severe Mental Illness After Participation in Virtual Reality Job Interview Training. Psychiatric Services, 66(11), 1173–1179. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Fleming MF, Wright MA, Losh M, Humm LB, Olsen D, & Bell MD (2015). Brief report: vocational outcomes for young adults with autism spectrum disorders at six months after virtual reality job interview training. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(10), 3364–3369. 10.1007/s10803-015-2470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Fleming MF, Wright MA, Roberts AG, Humm LB, Olsen D, & Bell MD (2015). Virtual reality job interview training and 6-month employment outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia seeking employment. Schizophrenia Research, 166(1–3), 86–91. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Ginger EJ, Wright K, Wright MA, Taylor JL, Humm LB, Olsen DE, Bell MD, & Fleming MF (2014). Virtual reality job interview training in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2450–2463. 10.1007/s10803-014-2113-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Pinto RM, Dawalt L, Smith JD, Sherwood K, Miles R, Taylor J, Hume K, Dawkins T, Baker-Ericzén M, Frazier T, Humm L, & Steacy C. (2020). Using community-engaged methods to adapt virtual reality job-interview training for transition-age youth on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 71, 101498. 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Sherwood K, Blajeski S, Ross B, Smith JD, Jordan N, Dawalt L, Bishop L, & Atkins MS (in press). Job interview and vocational outcomes among transition-age youth receiving special education pre-employment transition services. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Smith JD, Fleming MF, Jordan N, Brown CH, Humm L, Olsen D, & Bell MD (2017). Mechanism of Action for Obtaining Job Offers With Virtual Reality Job Interview Training. Psychiatric Services, 68(7), 747–750. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Demers A, McCrimmon AW, & Shaw KS (2017). Vocational training for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder: effectiveness of the practical assessment exploration system (PAES). Emerging Perspectives, 1(1), 10–19. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ep/article/view/30346 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Smith LE, & Mailick MR (2014). Engagement in vocational activities promotes behavioral development for adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Deveopmental Disorders, 44(6), 1447–1460. 10.1007/s10803-013-2010-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Test DW, Mazzotti VL, Mustian AL, Fowler CH, Kortering L, Kohler P. (2009). Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32(3), 160–181. 10.1177/0885728809346960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2019). Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/tables/2010-2018/national/asrh/PEPSYASEXN.pdf?# [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Education (2017). A Transition Guide to Postsecondary Education and Employment for Students and Youth with Disabilities. Washington, D.C.: Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/postsecondary-transition-guide-may-2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Walker Z, Lee SJE, Wienke W, & Tan DS (2019). A review of interview preparation via virtual and mixed reality for individuals with intellectual and developmental disorder. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 51, 87–97. 10.3233/JVR-191028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DM, & Esposito MCK (2018). Virtual reality in transition program for adults with autism: self-efficacy, confidence, and interview skills. Contemporary School Psychology, 1–9. 10.1007/s40688-018-0195-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehman P, Chan F, Ditchman N, & Kang HJ (2014). Effect of supported employment on vocational rehabilitation outcomes of transition-age youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a case control study. Intellectual & Developmental DisabilitieS, 52(4), 296–310. 10.1352/1934-9556-52.4.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehman P, Schall C, McDonough J, Sima A, Brooke A, Ham W, Whittenburg H, Brooke V, Avellone L, & Riehle E. (2020). Competitive employment for transitionaged youth with significant impact from autism: a multi-site randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Deveopmental Disorders, 50 (6), 1882–1897. 10.1007/s10803-019-03940-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ, Carlozzi NE, Slotkin J, Blitz D, Wallner-Allen K, Fox NA, Beaumont JL, Mungas D, Nowinski CJ, Richler J, Deocampo JA, Anderson JE, Manly JJ, Borosh B, Havlik R, Conway K, Edwards E, Freund L, King JW, Moy C, Witt E, & Gershon RC (2013). Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S54–64. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTAC (2020). Workforce Innovation Technical Assistance Center. http://www.wintac.org/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.