Abstract

Background:

Although a number of neuroimaging biomarkers for response have been proposed, none have been tested prospectively for direct effects on treament outcomes. This is the first prospective test of the clinical utility of the use of an imaging biomarker to select treatment for patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods:

Eligible participants (n=60) had a primary diagnosis of MDD and were assigned to either escitalopram or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) based on the fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) activity in the right anterior insula. The overall study remission rate after 12 weeks of treatment, based on endpoint Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score, was then examined for futilty and benefit of the strategy.

Results:

Remission rates demonstrated lack of futility at the end of Stage 1 [37% or 10/27], and the study proceeded to Stage 2. After adjustment for the change in Stage 2 sample size, the complete remission rate did not demonstrate evidence of benefit [37.7%, 95% CI 26.3 – 51.4%, p=0.38]. However, total remission rates (complete and partial remission) did reach significance in post-hoc analysis [49.1%, 95% CI 37.6 – 60.7%, p=0.020].

Conclusions:

The study shows some evidence for a role of the right anterior insula in the clinical choice of MDD monotherapy. The effect size, however, is insufficient for the use of insula activity as a sole predictive biomarker of remission. The study also demonstrates the logistical difficulties of establishing clinical utility of biomarkers.

Trial registration:

clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02137369): URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02137369

INTRODUCTION:

Psychiatry has recently been inundated with studies detecting possible biomarkers for treatment response in major depressive disorder (MDD) (1-3). One focus of this research has been identifying imaging predictors of treatment response that can be further mapped to underlying biological mechanisms. These studies have encompassed multiple methods of treatment and various imaging methods (4-6).

While most studies have focused on prediction of response status to various treatments, only a few directly address treatment selection. We previously characterized a treatment selection biomarker (TSB) using fluorodeoxyglucose F18 positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)(7, 8). Specifically, FDG-PET activity in the right anterior insula (rINS), relative to whole brain mean, was shown to be lower in those subjects who remitted to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and higher in those subjects who remitted to escitalopram (ESCIT), a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI). Given the increased cost of CBT over antidepressant medication treatment and the risks associated with medication, a biomarker of this nature could have considerable clinical utility. Despite the ultimate goal of identifying biomarkers that inform treatment recommendations in MDD, only a few studies have demonstrated external validity through replication in independent samples(4). Further, we know of none that have been externally validated using patient specific prediction(9); or tested prospectively for the demonstration of clinical utility(10, 11).

Establishing clinical utility, or efficacy of the biomarker, requires the comparison of remission rates in subjects randomized to: 1) use of the biomarker to guide treatment, or 2) some form of “usual care”. However, Phase III trials are very costly, and given the number of failed trials of this nature, it has been proposed (12) that a single-arm phase II trial of futility should precede any attempts to test for efficacy. Given that proof of the efficacy of a biomarker requires a formal test of the success of a treatment strategy rather than success of a treatment, the application of a futility design is a crucial intermediate step for prospectively developing biomarkers for clinical use. In the current study, the strategy being tested was to base the choice of MDD treatment, CBT or SSRI, on the normalized FDG-PET activity in the rINS.

Of note, the goal of the study was not to test the efficacy of either of the two treatments, which is already established; nor, was it to compare the efficacy of one treatment to another. Further, comparison of remission rates across groups is not valid in the context of the current, non-randomized design. Rather, we tested the benefit of the TSB by showing its effect on overall study remission rates. More specifically, we tested that use of the TSB results in 1) at minimum the expected response rate of other treatment strategies (lack of futility), and 2) a reasonable improvement over that base rate (evidence of benefit). To do this, we made use of a standard “two-stage” trial design (13) commonly used in cancer trials (14-16) to test the specified dual hypotheses.

METHODS AND MATERIALS:

Study Overview: InSuLa Assessed Needs for Depression (ISLAND)

The study design closely adhered to the design of the previous clinical trial that defined the biomarker prospectively tested in this report (7, 8, 17). Participants were recruited through the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program at Emory University via advertisements and clinician referrals from November 2014 to May 2019. The trial consisted of two 12-week phases. Phase 1 involved treatment with either CBT or an SSRI (escitalopram or sertraline). In Phase 2, non-remitters at week 12 received combination treatment with SSRI plus CBT, whereas remitters continued their initial treatment and were seen monthly for follow up. Because the primary hypothesis of the study evaluated outcomes at the end of Phase 1, Phase 2 results are not reported here. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Emory Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and its amendments and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02137369).

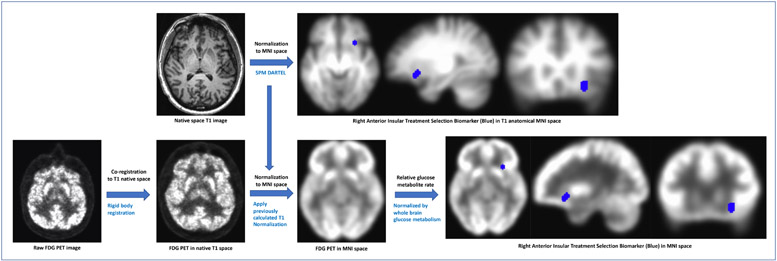

Right Anterior Insular Treatment Selection Biomarker

To prospectively assign each individual patient to either CBT or SSRI, we defined a region of interest (ROI) using the center of mass of the top 30% of voxels that distinguished the four remitter/treatment groups in the previously derived right anterior insula TSB (7). Relative glucose metabolic rate in the ROI was extracted and patients with values higher than the threshold (1.02437) were assigned to SSRI and equal and less than the threshold were assigned to CBT. New data from the operationalized ROI was extracted for the previous cohort to assess changes in distribution across studies. (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Treatment selection biomarker location and measurement

Subjects

Depressed adults aged 18 to 60 were screened for participation. Screening included a psychiatric interview, laboratory testing, medical history, physical exam, MRI screening form, and an electrocardiogram. Eligibility required a primary diagnosis of MDD without psychotic or catatonic features, as assessed by the Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Diagnoses (SCID-IV) and confirmed through a psychiatrist’s interview. Patients had to have at least moderate severity depression, defined as a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)(18) 17-item score ≥18 at screening and ≥15 at the baseline randomization visit. Psychiatric exclusion included a current diagnosis of a bipolar disorder, a psychotic disorder, or any primary psychiatric disorder other than MDD; diagnosis within the past 12 months of panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa; substance dependence within 12 months of the screening visit or substance abuse within 3 months; use of an antidepressant within 1 month of the pre-treatment PET scan or use of non-prescription agents (e.g., S-adenosyl methionine, n-3 fatty acids) within 2 weeks of the pre-treatment PET scan; current suicidal ideation requiring urgent clinical intervention; receipt of electroconvulsive therapy within six months of the screening visit; or lifetime history of failure to respond to four or more sessions of CBT for depression or to ≥6 week trials of both escitalopram (≥10 mg/day) and sertraline (≥50 mg/day). Additional exclusion criteria included current diabetes mellitus; current pregnancy or lactation; or a current medical or neurological condition that could contribute to depression or that might interfere with response to treatment. Concomitent medication details are in the Supplement.

Treatments and Outcomes

At the time of consent, patients were told that they would be randomly assigned to receive 12 weeks of treatment with either CBT or antidepressant medication. However, patients were actually assigned treatment based on the result of the pre-treatment PET scan. This deception, which was approved by the Emory IRB, was considered necessary to minimize placebo-responsiveness that may have resulted from patients believing they were “getting what their brain needed.” Patients were debriefed about the deception at their final study visit. The CBT delivered was Beck’s manual-based, depression-focused CBT (16 one-hour sessions over 12 weeks). The medication treatment was escitalopram (flexibly dosed from 10-30 mg/day), though patients who reported a previous failure to an adequate trial of escitalopram were treated with sertraline (flexibly dosed from 50-150 mg/day). Patients who were unable to tolerate escitalopram (n=4) were switched to sertraline before the week 4 visit. Doses of SSRIs were up titrated until remission was achieved or side effects prevented further dose increases. CBT sessions were scheduled twice weekly for the first 4 weeks, followed by weekly sessions for the subsequent 8 weeks. Patients returned to the clinic weekly for the first 4 weeks and then biweekly until week 12. At these visits, depressive symptoms were assessed using the HDRS administered by raters blinded to treatment assignment. At each visit, a study psychiatrist evaluated side effects and made dose adjustments. The primary outcome was remission, defined as a HDRS score ≤7 at both weeks 10 and 12. Response was defined as a ≥50% reduction in HDRS score from baseline to week 12. Of the 77 participants consented, 60 patients were assigned, and 50 completed 12 weeks of treatment (9 CBT, 41 SSRI; Supplement).

Imaging Acquisition and Preprocessing

Prior to treatment randomization, brain glucose metabolism was measured via PET (High-Resolution Research Tomograph, Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA), using standard methods without arterial blood sampling. The PET image acquisition method matched the original treatment selection biomarker (TSB) study (7). For each scan, a 10miC dose of 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) was administered intravenously, with a 20-minute 3-D image acquisition beginning 40 minutes after tracer injection. During uptake, patients remained supine, awake, and resting with eyes closed and ears uncovered. Patients were asked to avoid ruminating on any one topic during the 40- minute FDG uptake period. Raw emission images were corrected for injected dose and attenuation (using Cs-137, 6-minute transmission scan), reconstructed, and smoothed to an in-plane resolution of 4.0 mm full width at half maximum. To provide precise and reproducible anatomical localization of the anterior insula activity from each patient PET scan, a high-resolution T1-weighted structural MRI scan was separately acquired for spatial normalization procedures and anatomical reference using 3T Tim Trio scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) with following parameters: Magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo sequence, TR/TI/TE=2,600/900/3.02 ms, flip angle=8°, voxel resolution=1X1X1 mm, number of slices=196, matrix=224X256. Attenuation corrected PET images were co-registered to corresponding T1-weighted anatomical images using a rigid body linear transform and subsequently written into standard Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 1-mm voxel space using a non-linear transform calculated from the T1-weighted image (DARTEL, SPM8; Welcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, England; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Spatially normalized images were smoothed with an 8mm FWHM Gaussian kernel and corrected for differences in whole brain global mean activity (19).

Calculation of target remission rates:

For the current study we chose the outcome of remission as the primary target, as it is considered optimal treatment outcome(20). We used a minimum remission rate (% of subjects that meet crieria) of 35% as the futility benchmark after examining the published remission rates of the larger 12-week studies of treatment response at the time of protocol submission (2013): Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): 27.5% (21), Research Evaluating the Value of Augmenting Medication With Psychotherapy (REVAMP): 22.3% (22), Nefazadone vs Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP): 29.3%, (23); and included the randomized treatment study generating the insula biomarker: 36.9% (24). Although this resulted in a weighted average of 27.1%, we chose the liberal estimate of 35% because we were performing the new study at the same site. For the benefit benchmark we chose a 50% remission rate, or an increase of 15% over the expected remission rate, as evidence that the treatment strategy would be an improvement over the expected rate and therefore adequate for further exploration.

Sample size calculation:

The two-stage design (13) was used to ensure a remission rate of at least 35% (within error), providing a futility test at alpha=0.05, at the first stage. To meet that threshold, 10 of the first 27 completers (37%) were required to meet remission criteria. The second stage was then powered to detect, within error, a remission rate >= 50% indicating the benefit of the treatment-assignment strategy (value of the biomarker) with a power =0.80. For the second stage it was determined that a sample of n=50 additional completers would be needed (total n=77), and if 33 or more completers remitted (raw rate of 42.9%), the strategy would be considered adequate for further phase III trials. The power of the current study as well as the estimates of remission rates for previous studies were based on completers as that provides the best estimate of the rate for clinical demonstration of the use of the biomarker. Note that the required percentages are lower than the set limits due to the procedure allowing for error, the use of exact binomial computation, and the conditional nature of the testing (two stage adaptive design).

Analysis incorporating partial remission:

To fully explore the evidence for adequacy of the biomarker, we did a post-hoc analysis incorporating those subjects who met response criterion (>=50%) as partial remitters. Most cancer trials utilizing the design calculate the total response (TR) count as the sum of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) counts, because both are considered evidence of benefit(15). While the majority of two-stage cancer studies treat both PR and CR as equivalent (14-16, 25), more recent methods have been proposed to target TR as a weighted sum of CR and PR. Thus, we adapted a weighted sum method (26) to calculate post-hoc estimates of the “all source” remission rate that incorporate partial remission.

The choice of weight for a partial remission is often arbitrary; however, we can estimate the weight using data from published studies. For this estimate we used the four studies used for the target remission rate (21-24) along with two additional studies published more recently (27, 28) that provided both response and remission estimates. For one study we used the raw data at week 12 for the HDRS17 to get estimates, which is different from the study target (22). Given that the baseline inclusion for the HDRS17 was >= 15 for all studies, it is guaranteed that all those subjects who meet remission criteria will also meet response criteria. Thus, an estimate of the weight can be calculated by using the total count of responders and remitters across studies to get an estimate of the ratio [calculations included in Supplement]. Because the STAR*D trial (21) did not have information on completers, we calculated the ratio with and without including these data. The remitter/responder ratio estimate was 0.66 including STAR*D and 0.74 without STAR*D data. Given that missing outcomes were imputed as nonresponders for STAR*D, the given remission rates are expected to be lower than completer rates, and thus the estimate is probably closer to the upper limit of 0.74.

Calculation of remission estimates:

Due to the conditional nature of the design, special calculations must be employed to determine adequate estimates of the remission rates and confidence intervals(29). Most importantly, raw remission rates are biased as they do not consider the adaptive nature of the trial, and thus do not reflect the true estimates. More importantly, the actual sample size of the second stage is often different from the planned sample size, due to recruitment or funding issues. Given the common nature of the second stage sample size changing post-hoc, Koyama and Chen(30) developed a method to accurately calculate the remission rate, confidence interval and significance value, adjusting for the adaptive design as well as any changes in sample size. Thus, although the orginal design called for more subjects, the significance values have all been adjusted for the change in stage 2 sample size, and are calculated using both the originally planned (n=77) and the obtained (n=50) sample size. Thus these tests are adequately powered for inference purposes and therefore can be considered definitive.

RESULTS:

Trial results:

The demographic and clinical data of the participants are shown in Table 1. The first stage showed an adequate rate of remission (10/27 = 37%) to pass to the second stage. An additional four subjects met criterion for partial remission (change in HDRS17 ≥ 50%) criteria during the first stage. Therefore, the first stage test demonstrated acceptance for further study on the target of complete remission. The second stage, however, did not reach the recruitment goal of a total of 77 completers of 12 weeks of treatment (27 stage 1, 50 stage 2) by the end of the funding period. The second stage only recruited an additional 23 subjects for a final total of 50 completers. However, using the method of Koyama and Chen(30) we were able to estimate the final rate of complete remission, accounting for the truncated recruitment, to be 37.7% (95% CI 26.3 – 51.4%, p=0.38; Figure 2]. Therefore, the primary outcome criterion was not met.

Table 1:

Demographics and clinical characteristics of testing and derivation samples.

| N(%) | range | N(%) | range | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical measure | Testing sample (n=60) |

Derivation sample (n=80) |

Test statistic | p-value | |||

| Age in years, mean(SD) | 37.9 (11.2) | 19 - 59 | 41.7 (8.3) | 20 - 55 | t= 2.35 | 0.020 | |

| Sex (Male) | 17 (28.3) | 33 (41.3) | X2=2.49 | 0.114 | |||

| Number of episodes | 1 | 18 (30.0) | 22 (27.8) | X2=0.17 | 0.918 | ||

| 2 | 16 (26.7) | 20 (25.3) | |||||

| 3+ | 26 (43.3) | 37 (46.8) | |||||

| Married or cohabitating | 22 (36.7) | 36 (45.0) | X2=0.96 | 0.322 | |||

| Race | White | 34 (56.7) | 57 (71.3) | X2=4.65 | 0.098 | ||

| Black | 15 (25.0) | 17 (21.3) | |||||

| Hispanic/other | 11 (18.3) | 6 (7.5) | |||||

| High school education or higher | 59 (100.0) | 78 (100.0) | ---- | ---- | |||

| Full time employment | 33 (55.0) | 45 (56.3) | X2=0.02 | 0.863 | |||

| Current anxiety disorder | 37 (61.7) | 32 (40.0) | X2=6.44 | 0.011 | |||

| Previous psychotherapy | 18 (30.0) | 43 (53.8) | X2=7.87 | 0.005 | |||

| Chronicity (current episode ≥ 2 years) | 34 (56.7) | 32 (41.0) | X2=3.33 | 0.068 | |||

| Duration of illness (years), mean(SD) | 14.5 (10.7) | 0.5 - 53 | 14.9 (10.9) | 0.5 - 42 | t=0.23 | 0.819 | |

| HDRS 17 total, mean (SD) | 18.3 (3.4) | 15 - 30 | 19.7 (3.5) | 15 - 28 | t=2.34 | 0.021 | |

| HARS total, mean (SD) | 15.0 (4.4) | 5 - 24 | 15.3 (4.9) | 7 - 31 | t=0.42 | 0.673 | |

| Number of lifetime AD trials, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0 - 6 | 1.5 (1.4) | 0 - 6 | t=1.85 | 0.066 |

HDRS - Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. HARS - Hamilton anxiety rating scale, AD - antidepressant

Figure 2:

Remission rates achieved with use of treatment selection biomarker (TSB)

For our post-hoc analysis, we used the same method to calculate total remission rates using a weighted sum of complete and partial remission. Given the use of the exact binomial for the calculation, we could only use weights that permitted integer counts for the partial remitters. Given that four subjects in each stage (total of eight subjects) achieved >=50% change in HDRS17 without reaching remission, we were required to use a weight of either 0.5 (two subjects per stage) or 0.75 (three subjects per stage) to estimate the total remission rate. These calculations resulted in an estimated true rate of remission of 45.2% (95% CI 33.8 – 57.1%, p=0.071) for a ratio of 0.5 and 49.1% (95% CI 37.6 – 60.7, p=0.020) for a ratio of 0.75 [Figure 2]. Given the calculated average ratio from recent studies was between 0.65 and 0.74, we can conclude that the significance level of 0.05 is met for total remission. This provides evidence that the use of PET activity in the right insula may be a useful stratification tool for CBT versus SSRI treatment, pending further support in larger, more definitive studies.

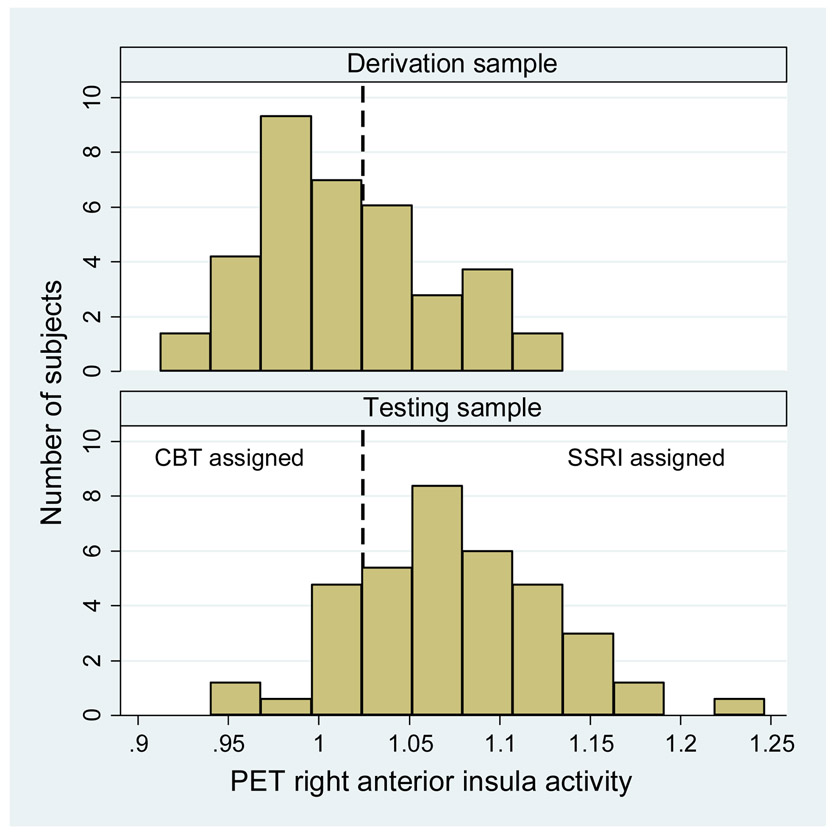

Distribution and patient allocation:

The distribution of the normalized rINS shifted to a higher average in the new cohort [Figure 3]. Due to this shift, only 11/60 subjects (18.3%) were assigned to CBT, whereas our original study had randomized treatment, so the distribution of right insula was more even (44 SSRI and 33 CBT “type”) using the range of rINS. This was unexpected, so we pursued possible sources of the variability. However, it is critical to note that the design does not require any specific allocation to treatment, only an overall remission rate within a certain threshold.

Figure 3:

Distribution of right anterior insula values in derivation (n=80) and testing (n=60) samples

The current study (testing sample) were younger, and had lower baseline severity than the derivation sample [Table 1]. More notably, however, the testing sample had higher prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorder (62% vs 40%) and lower prevalence of previous psychotherapy (30% vs 54%). To determine if any of these associations may have resulted in the shift in distribution of the rINS, we tested for association between the rINS and the demographics that differed between cohorts. Given that the variance of the measure within the rINS was comparable across cohorts (0.08 (0.01) vs 0.09 (0.02), t=−1.07, p=0.287), there was no direct evidence of location sampling effects on the difference in distribution. Thus, we combined across samples to test associations with demographics. Baseline severity and previous psychotherapy were not associated with the rINS, however higher age was significantly associated with lower insula activity (r=−0.22, p=0.01). Current anxiety disorder was also significantly associated with higher insula activity (1.03 (0.05) vs 1.06 (0.06), t=3.07, p=0.003). Although this was not uncovered in the first cohort, it appears these differences in sample composition may have been the cause of the shift in distribution.

CONCLUSIONS:

Research into biomarkers for antidepressant treatment response are pursued with the ultimate goal of providing more informed treatment decisions. The current study speaks directly to that goal by testing for evidence of an increased rate of remission when using guided treatment. To our knowledge this is the first attempt to test the use of a TSB for MDD in this prospective fashion. The primary target of complete remission did not meet threshold; however, incorporating partial remission as evidence of clinical utility did demonstrate statistically significant evidence of benefit. The choice to target remission as the primary outcome may been too stringent in hindsight, as we were only looking for evidence of benefit and not treatment success as with all Phase II designs. Our original choice was based on the fact that there should be a high threshold for any biomarker that proposes changes in treatment. However, use of response (50% change) as an outcome is still commonly used in studies predicting treatment response using demographic, genetic and neuroimaging (1, 4, 31-33) biomarkers, so the post-hoc results have clinical merit. However, even with the appropriate sample size adjustments, it is clear from the data that the use of the TSB did not produce an overwhelming increase in remission rates. Thus, it is unlikely the current PET biomarker would be further pursued as a single TSB, particularly given that we are looking at a costly imaging measure. However, the evidence does support that activity in the right anterior insula (or perhaps the salience network) may identify patients who are likely to respond to CBT, and thus could be a building block for a multi-factorial approach for treatment selection.

Several aspects of the current study might affect the generalizability of the results. The study targeted a minimum remission rate of 35%, with a 15% benefit margin; this was based on the most readily available rates at the time of the study submission. More recent studies indicate perhaps larger remission rates in previously untreated or minimally treated patients (27, 28) with a rate of 45.4% in completers. However, the cumulative average in the larger studies of active treatment to date (21-24, 27, 28, 34) still produce an overall average remission rate of 32.4% in completers; thus, this target would still be considered reasonable for futility in chronic patients. Therefore, patient population needs to be a factor in deciding future futility targets for prospective testing. In addition, very few patients were assigned to the CBT arm due to a shift in the insula distribution, which could only be examined after the fact. Thus, the current trial may not represent the best test of the insula measure. It is notable however, that even with this unforeseen shortcoming, evidence of benefit was demonstrated.

What is most informative about the current study is the number of challenges encountered that can inform the testing and use of biomarkers. These include errors induced through the definition of the biomarker used to allocate patients to treatment or predict patient-specific response probability. More succinctly, the use of an imaging measure to assign treatment can induce error, even when the biomarker is valid. For the current study, we chose a cutoff of normalized activity at a singular threshold since this clearly separated non-responders and remitters to differential treatments in the original study that identified the biomarker. However, given individual variation and errors in measurement, it might be more reasonable to incorporate a “buffer” zone around the cutoff to minimize classification errors in future studies that test biomarkers. It has been pointed out that machine learning models may provide a stronger foundation for establishing possible biomarkers (9), as they focus on patient specific prediction. However, this benefit may also come with a cost as they often require hundreds to thousands of sample-specific coefficients that must be applied prospectively, which could compound issues with measurement error.

The main source of variation, however, is likely differences in patient population, which creates logistical challenges for the use of biomarkers to aid in treatment recommendations. This more likely than not impairs the implementation of these biomarkers in clinical practice, and more about this aspect of the research goal needs to be discussed going forward. In addition, how to deal with sample heterogeneity in implementation is less clear. Many approaches consider patient characteristics as one of many possible competing predictors (1). However, in practice, most biomarkers are tested for independence from clinical predictors (4, 34) in order to be considered viable. Thus the question remains whether relevant clinical predictors should be considered as part of the classification process or are best used as stratification features in any treatment selection algorithm.

Finally, although much exposition has been focused on the best way to derive (35) and validate biomarkers(9), very little has been said about how to use them to effect outcomes. The current study shows that the prospective testing of biomarkers of response to various treatments is well served to include the one arm study of futility/benefit before the expense of a Phase III comparison to control strategies. Given that recent prospective studies of genetic biomarkers of antidepressant response have demonstrated questionable utility and cost-effectiveness when directly testing for improvement in outcomes (11), the use of futility designs is warranted going forward. Even more importantly, quantifying the evidence of benefit (effect size) is crucial in determining the viability of a biomarker for further testing. More recent “adaptive” designs that further reduce the sample size required for the second stage (36) can be used to produce results even faster and with less resources, making this an appealing option for future prospective testing of biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCE TABLE

| Resource Type | Specific Reagent or Resource | Source or Reference | Identifiers | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add additional rows as needed for each resource type | Include species and sex when applicable. | Include name of manufacturer, company, repository, individual, or research lab. Include PMID or DOI for references; use “this paper” if new. | Include catalog numbers, stock numbers, database IDs or accession numbers, and/or RRIDs. RRIDs are highly encouraged; search for RRIDs at https://scicrunch.org/resources. | Include any additional information or notes if necessary. |

| Antibody | NA | |||

| Bacterial or Viral Strain | NA | |||

| Biological Sample | NA | |||

| Cell Line | NA | |||

| Chemical Compound or Drug | NA | |||

| Commercial Assay Or Kit | NA | |||

| Deposited Data; Public Database | NA | |||

| Genetic Reagent | NA | |||

| Organism/Strain | NA | |||

| Peptide, Recombinant Protein | NA | |||

| Recombinant DNA | NA | |||

| Sequence-Based Reagent | NA | |||

| Software; Algorithm | NA | |||

| Transfected Construct | NA | |||

| Other | NA |

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Tanja Mletzko Crowe, Kathleen Helms, Amber Lechner, and Valerie Cruz for their assistance as study coordinators, the CBT therapists Allison Lopilato, Noriel Lim, and Devon Loparo, JungHo Cha for his assistance in imaging data preprocessing, and all the participants who donated their time to the study.

Funding source: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 MH073719.

Role of Funding Source: The funding sources took no part in the design or conduct of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Mayberg has received consulting and licensing fees from Abbott Labs. Dr. Dunlop has received research support from Acadia, Compass Pathways, Aptinyx, NIMH, Sage, and Takeda, and has served as a consultant to Greenwich Biosciences, Myriad Neuroscience, Otsuka, Sage, and Sophren Therapeutics. Dr. Rakofsky has received research support from Compass Pathways, Otsuka, and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and has received honoraria from SMI Clinical Advisor. Dr. Craighead receives book royalties from John Wiley & Sons; he has received research support from NIH, the Fuqua family foundations, the Mary and John Brock Foundation, and he is a consultant to the George West Mental Health Foundation and AIM for Mental Health Foundation. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Gillett G, Tomlinson A, Efthimiou O, Cipriani A (2020): Predicting treatment effects in unipolar depression: A meta-review. Pharmacol Ther. 212:107557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang S-G, Cho S-E (2020): Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Predicting Treatment Response and Recurrence of Major Depressive Disorder. International journal of molecular sciences. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitenstein B, Scheuer S, Holsboer F (2014): Are there meaningful biomarkers of treatment response for depression? Drug Discov Today. 19:539–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlop K, Talishinsky A, Liston C (2019): Intrinsic Brain Network Biomarkers of Antidepressant Response: a Review. Current psychiatry reports. 21:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu CH, Steiner H, Costafreda SG (2013): Predictive neural biomarkers of clinical response in depression: a meta-analysis of functional and structural neuroimaging studies of pharmacological and psychological therapies. Neurobiol Dis. 52:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao S, Calhoun VD, Sui J (2018): Machine learning in major depression: From classification to treatment outcome prediction. CNS Neurosci Ther. 24:1037–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrath CL, Kelley ME, Holtzheimer PE, Dunlop BW, Craighead WE, Franco AR, et al. (2013): Toward a neuroimaging treatment selection biomarker for major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 70:821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, McGrath CL, Craighead WE, Mayberg HS (2015): Preliminary Findings Supporting Insula Metabolic Activity as a Predictor of Outcome to Psychotherapy and Medication Treatments for Depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 27:237–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bzdok D, Varoquaux G, Steyerberg EW (2020): Prediction, Not Association, Paves the Road to Precision Medicine. JAMA Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbert D, Neves-Pereira M, Baidya R, Cheema S, Groleau S, Shahmirian A, et al. (2018): Genetic testing as a supporting tool in prescribing psychiatric medication: Design and protocol of the IMPACT study. J Psychiatr Res. 96:265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenblat JD, Lee Y, McIntyre RS (2017): Does Pharmacogenomic Testing Improve Clinical Outcomes for Major Depressive Disorder? A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials and Cost-Effectiveness Studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 78:720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palesch YY, Tilley BC, Sackett DL, Johnston KC, Woolson R (2005): Applying a phase II futility study design to therapeutic stroke trials. Stroke. 36:2410–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon R (1989): Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 10:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maki RG, Kraft AS, Scheu K, Yamada J, Wadler S, Antonescu CR, et al. (2005): A multicenter Phase II study of bortezomib in recurrent or metastatic sarcomas. Cancer. 103:1431–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montemurro M, Cioffi A, Domont J, Rutkowski P, Roth AD, von Moos R, et al. (2018): Long-term outcome of dasatinib first-line treatment in gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A multicenter, 2-stage phase 2 trial (Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research 56/07). Cancer. 124:1449–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman EJ, Dunn LA, Schoder H, Ho AL, Baxi SS, Ghossein RA, et al. (2019): Phase 2 study of vascular endothelial growth factor trap for the treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer. Cancer. 125:2984–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGrath CL, Kelley ME, Dunlop BW, Holtzheimer PE 3rd, Craighead WE, Mayberg HS (2014): Pretreatment brain states identify likely nonresponse to standard treatments for depression. Biological psychiatry. 76:527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton M (1960): A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy SH, Konarski JZ, Segal ZV, Lau MA, Bieling PJ, McIntyre RS, et al. (2007): Differences in brain glucose metabolism between responders to CBT and venlafaxine in a 16-week randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 164:778–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller MB (2004): Remission versus response: the new gold standard of antidepressant care. J Clin Psychiatry. 65 Suppl 4:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, et al. (2006): Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 163:28–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocsis JH, Gelenberg AJ, Rothbaum BO, Klein DN, Trivedi MH, Manber R, et al. (2009): Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression: the REVAMP Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 66:1178–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, Arnow B, Dunner DL, Gelenberg AJ, et al. (2000): A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N Engl J Med. 342:1462–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Mletzko TC, Velasquez CM, Craighead WE, Mayberg HS (2012): Depression beliefs, treatment preference, and outcomes in a randomized trial for major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 46:375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paik PK, Kim RK, Ahn L, Plodkowski AJ, Ni A, Donoghue MTA, et al. (2020): A Phase II Trial of Albumin- Bound Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Stage IV Squamous Cell Lung Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 26:1796–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin SPC, T.T. (2000): Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials with differentiation of complete and partial responses. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods. 29:923–940. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlop BW, Kelley ME, Aponte-Rivera V, Mletzko-Crowe T, Kinkead B, Ritchie JC, et al. (2017): Effects of Patient Preferences on Outcomes in the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PReDICT) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 174:546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saveanu R, Etkin A, Duchemin AM, Goldstein-Piekarski A, Gyurak A, Debattista C, et al. (2015): The international Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D): outcomes from the acute phase of antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 61:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung SH, Kim KM (2004): On the estimation of the binomial probability in multistage clinical trials. Stat Med. 23:881–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koyama T, Chen H (2008): Proper inference from Simon's two-stage designs. Stat Med. 27:3145–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colle R, Deflesselle E, Martin S, David DJ, Hardy P, Taranu A, et al. (2015): BDNF/TRKB/P75NTR polymorphisms and their consequences on antidepressant efficacy in depressed patients. Pharmacogenomics. 16:997–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato M, Serretti A (2010): Review and meta-analysis of antidepressant pharmacogenetic findings in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 15:473–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey NW, Hoy KE, Rogasch NC, Thomson RH, McQueen S, Elliot D, et al. (2019): Differentiating responders and non-responders to rTMS treatment for depression after one week using resting EEG connectivity measures. J Affect Disord. 242:68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chin Fatt CR, Jha MK, Cooper CM, Fonzo G, South C, Grannemann B, et al. (2020): Effect of Intrinsic Patterns of Functional Brain Connectivity in Moderating Antidepressant Treatment Response in Major Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 177:143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackford JU (2017): Leveraging Statistical Methods to Improve Validity and Reproducibility of Research Findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 74:119–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shan GZ H;Jiang T (2019): Adaptive two-stage optimal designs for phase II clinical studies that allow early futility stopping. Sequential analysis Design Methods and Applications. 38:199–213. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.