Abstract

BACKGROUND

Treatment guidelines for prediabetes primarily focus on glycemic control and lifestyle management. Few evidence-based cardiovascular and kidney risk-reduction strategies are available in this population.

OBJECTIVES

This study sought to characterize cardiovascular and kidney outcomes across the glycemic spectrum.

METHODS

Among participants in the UK Biobank without prevalent type 1 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease, Cox models tested the association of glycemic exposures (type 2 diabetes [T2D], prediabetes, normoglycemia) with outcomes (atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [ASCVD], chronic kidney disease [CKD], and heart failure), adjusting for demographic, lifestyle, and cardiometabolic risk factors.

RESULTS

Among 336,709 individuals (mean age: 56.3 years, 55.4% female), 46,911 (13.9%) had prediabetes and 12,717 (3.8%) had T2D. Over median follow-up of 11.1 years, 6,476 (13.8%) individuals with prediabetes developed ≥1 incident outcome, of whom only 802 (12.4%) developed T2D prior to an incident diagnosis. Prediabetes and T2D were independently associated with ASCVD (prediabetes: adjusted HR [aHR]: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.08–1.15; P < 0.001; T2D: aHR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.37–1.51; P < 0.001), CKD (prediabetes: aHR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.02–1.14; P < 0.001; T2D: aHR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.46–1.69; P < 0.001), and heart failure (prediabetes: aHR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.01–1.14; P = 0.03; T2D: aHR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.14–1.37; P < 0.001). Compared with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) <5.0%, covariate-adjusted risks increased significantly for ASCVD above HbA1c of 5.4%, CKD above HbA1c of 6.2%, and heart failure above HbA1c of 7.0%.

CONCLUSIONS

Prediabetes and T2D were associated with ASCVD, CKD, and heart failure, but a substantial gradient of risk was observed across HbA1c levels below the threshold for diabetes. These findings highlight the need to design risk-reduction strategies across the glycemic spectrum.

Keywords: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, prediabetes, prevention, type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is well-recognized to be closely interlinked with risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure, and associated mortality (1–5). These conditions commonly coexist in patients with T2D, and multiple intersecting comorbidities contribute additively to poorer prognosis (3,5–7). Therapies that reduce cardiovascular and kidney risk in T2D, such as the sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), have now been established as a new therapeutic standard and are recommended independent of glycemic control considerations (8).

However, dysglycemia in the absence of T2D, termed prediabetes, is more common than diabetes, affecting >1 in 3 US adults and 1 in 5 US adolescents (9,10). Although treatment guidelines for prediabetes focus on glycemic control and prevention of progression to T2D, patients may experience cardiovascular and kidney events even without progression to frank T2D (11–13). In addition, prediabetes has been associated with subclinical alterations in cardiac structure and function (14,15). Whereas some have questioned the validity and usefulness of the “prediabetes” label as one of potential overdiagnosis (16), few data exist that comprehensively evaluate the risk of cardio-renal-metabolic outcomes across the glycemic spectrum, with a specific focus on the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) range below T2D diagnostic thresholds.

Here, we leveraged the UK Biobank’s large cohort size, comprehensive and uniform phenotyping, and longitudinal follow-up to test the association of baseline HbA1c and prediabetes/T2D status with incident ASCVD, CKD, and heart failure among >330,000 individuals without known cardiovascular or kidney disease.

METHODS

STUDY COHORT.

The UK Biobank is a prospective, observational, population-based cohort of >500,000 adult residents of the United Kingdom who were 40 to 69 years of age at the time of recruitment between 2006 and 2010 (17). At enrollment, participants provided informed consent and detailed information on sociodemographic data, lifestyle factors, medical history, and medication use. Reported medical history was verified by a trained study nurse. In addition, participants underwent physical assessment, including measurement of anthropomorphic data and vital signs, and provided blood and urine specimens for laboratory analysis. Participants were followed for the development of incident diagnoses through linkage to national health records and follow-up study visits (17). In the present study, follow-up in the UK Biobank occurred through March 31, 2020. This analysis included UK Biobank subjects with HbA1c measured at enrollment; HbA1c <15%; complete covariate data; and no prevalent type 1 diabetes, ASCVD, heart failure, or CKD at baseline. This study was conducted under UK Biobank application number 7089. The UK Biobank received ethics approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee. The Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board approved secondary analysis of these data.

EXPOSURE AND COVARIATES.

The primary study exposure was T2D (defined as self-reported T2D, HbA1c ≥6.5%, and/or use of insulin) vs prediabetes (defined as no self-reported T2D and HbA1c ≥5.7 and <6.5%, in accordance with the American Diabetes Association definition [18]) vs normoglycemia (defined as no self-reported T2D and HbA1c <5.7%). HbA1c as a continuous variable constituted a secondary exposure.

Race was self-reported and categorized as Asian, Black, White, and Mixed/Other. The Townsend deprivation index is a composite measure of socioeconomic deprivation based on employment, home and car ownership, and household crowding and was assigned by the UK Biobank based on subjects’ postal code of residence. Participants reported their history of tobacco use (current vs former vs never), current alcohol consumption, daily servings of vegetable and fresh fruit intake, history of any physician-diagnosed cancer, and medication use at enrollment. Height, weight, and blood pressure were recorded by trained study staff.

Procedures for collecting and processing baseline blood and urine samples have been previously described, including measurement of HbA1c (VARIANT II TURBO, Bio-Rad); total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (AU5800, Beckman Coulter, Brea, California); and urinary microalbumin and creatinine (AU5400, Beckman Coulter) (19). As the lower limit of detection of the urine microalbumin assay was 6.7 mg/L, the urinary microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio was dichotomized as ≥30 mg/g vs <30 mg/g for analyses.

OUTCOMES.

The coprimary study outcomes were: 1) ASCVD, defined as a composite of coronary artery disease (CAD), ischemic stroke, and peripheral artery disease; 2) CKD; and 3) heart failure. Secondary outcomes included individual ASCVD subtypes and all-cause mortality. Incident disease diagnoses were defined as a newly diagnosed fatal or nonfatal condition ascertained by the appearance of a qualifying International Classification of Disease or procedural code in the subject’s study record (Supplemental Appendix). Incident CAD was defined using codes corresponding to myocardial infarction, coronary artery revascularization, chronic ischemic heart disease, and ischemic cardiomyopathy; ischemic stroke was defined using codes corresponding to acute ischemic cerebrovascular events; and peripheral artery disease was defined using codes corresponding to atherosclerosis of the aorta or peripheral arteries, peripheral arterial revascularization procedures, and lower extremity amputation (Supplemental Appendix).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES.

Baseline characteristics were compared by glycemic status using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, as appropriate, and using the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables. Absolute incidence rates and rate differences for study outcomes were calculated per 1,000 person-years of follow-up. The population attributable risk proportion for prediabetes was calculated for each outcome as the difference between overall risk and the risk among subjects without prediabetes and expressed as a proportion of overall risk; similarly, the population attributable risk proportion for T2D was calculated as the difference between overall risk and risk among subjects without T2D, expressed as a proportion of overall risk.

Multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazard models tested the association of glycemic exposures with cardiometabolic outcomes. Sparsely adjusted models included age, age2, sex, and race as covariates. Fully adjusted models further adjusted for Townsend deprivation index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, vegetable/fresh fruit intake, history of cancer, systolic blood pressure (SBP), antihypertensive medication use, non-HDL cholesterol, cholesterol-lowering medication use, body mass index, C-reactive protein, and the urinary microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio. Models testing HbA1c as a continuous exposure were further adjusted for use of insulin. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using Schoenfeld residuals. Sensitivity analyses incorporated incident T2D as a time-varying covariate.

Secondary analyses examined the accumulation of multimorbidity by glycemic status in the study cohort. To examine the sequence of incident disease diagnoses among individuals with multiple outcomes (ASCVD, CKD, and/or heart failure), the first, second, and (where applicable) third diagnoses were ascertained based on time to diagnosis. If 2 diagnoses were made simultaneously, order was assigned based on overall frequency of outcomes in the data set (ASCVD, then CKD, then heart failure). Among individuals with incident ASCVD, CKD, or heart failure as a first outcome, Cox models tested the association of baseline glycemic status with development of a second outcome, with follow-up beginning at the first diagnosis. Finally, to identify predictors of elevated risk among individuals with prediabetes, exploratory models tested interactions between each covariate and glycemic status (prediabetes vs T2D) as well as with HbA1c as a continuous variable. In these models, SBP was adjusted for antihypertensive medication use by adding 15 mm Hg as was done previously (20), and non-HDL cholesterol was adjusted for cholesterol-lowering medication use by dividing by 0.68 as was done previously (21). Covariates found to have at least nominally significant (P < 0.05) interactions with glycemic status (diabetes status, HbA1c, or both) for ≥2 study outcomes were used to define a “high-risk” subgroup of prediabetes in post hoc analyses, where cumulative incidence of study outcomes was compared between high-risk and other prediabetic individuals.

Given 3 coprimary outcomes, P < 0.05/3 = 0.017 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

STUDY COHORT.

Among 336,709 individuals without prevalent ASCVD, CKD, or heart failure (Supplemental Figure 1), 277,081 (82.3%) had normoglycemia, 46,911 (13.9%) had prediabetes, and 12,717 (3.8%) had T2D at baseline. The overall mean ± SD age of the cohort at baseline was 56.3 ± 8.1 years, and 186,572 participants (55.4%) were female. The median HbA1c was 5.36% (interquartile range [IQR]: 5.14%, 5.59%). Participants were followed up over a median of 11.1 (IQR: 10.4, 11.7) years.

Compared with individuals with normoglycemia, those with T2D and prediabetes were older, more likely to be non-White, had lower socioeconomic status, and were more likely to be current or former smokers (Table 1). In addition, individuals with T2D and prediabetes had higher body mass index; higher SBP despite higher rates of antihypertensive medication use; lower HDL cholesterol; and higher triglycerides, microalbuminuria, and C-reactive protein levels.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Type 2 Diabetes (n = 12|717) | Prediabetes (n = 46|911) | Normoglycemia (n = 277,081) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 59.1 ± 7.2 | 59.4 ± 7.0 | 55.6 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Female | 5,152 (40.5) | 26,452 (56.4) | 154,968 (55.9) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| White | 11,049 (86.9) | 42,564 (90.7) | 266,962 (96.3) | |

| Black | 450 (3.5) | 1,457 (3.1) | 2,528 (0.9) | |

| Asian | 906 (7.1) | 1,899 (4.0) | 4,153 (1.5) | |

| Mixed/Other | 312 (2.5) | 991 (2.1) | 3,438 (1.2) | |

| Townsend deprivation index | −1.4 (−3.2 to 1.8) | −2.0 (−3.6 to 0.8) | −2.3 (−3.7 to 0.1) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| Current | 1,427 (11.2) | 6,891 (14.7) | 25,931 (9.4) | |

| Former | 5,138 (40.4) | 16,435 (35.0) | 93,332 (33.7) | |

| Never | 6,152 (48.4) | 23,585 (50.3) | 157,818 (57.0) | |

| Alcohol intake | 1–2 times weekly (special occasions only, 3–4 times weekly) | 1–2 times weekly (special occasions only, 3–4 times weekly) | 1–2 times weekly (1–3 times monthly, 3–4 times weekly) | <0.001 |

| Total portions of vegetables and fresh fruit daily | 7 (5 to 9) | 7 (5 to 9) | 6 (5 to 9) | <0.001 |

| History of cancer | 1,074 (8.4) | 4,258 (9.1) | 19,895 (7.2) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.6 ± 5.8 | 28.9 ± 5.2 | 26.8 ± 4.4 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 144.9 ± 18.3 | 143.7 ± 19.5 | 138.8 ± 19.5 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive medication use | 6,803 (53.4) | 13,063 (27.8) | 40,471 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol-lowering medication use | 7,944 (62.5) | 11,296 (24.1) | 27,042 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Insulin use | 1,322 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 186.1 ± 46.4 | 225.0 ± 46.3 | 224.1 ± 41.5 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 113.6 ± 35.0 | 142.1 ± 35.2 | 140.2 ± 31.9 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 176.2 (123.1 to 249.9) | 153.1 (108.7 to 216.9) | 125.2 (89.2 to 180.6) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 46.5 ± 12.1 | 53.8 ± 14.0 | 57.5 ± 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.82 ± 0.20 | 0.82 ± 0.17 | 0.81 ± 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g | 1,761 (13.8) | 2,548 (5.4) | 9,459 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 2.1 (1.0 to 4.4) | 1.9 (1.0 to 3.9) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.5) | <0.001 |

Values are mean ± SD, n (%), or median (interquartile range). Characteristics were compared by glycemic status using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, as appropriate, and using the Pearson chi-squared test for categorical variables.

HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

INCIDENT DISEASE OUTCOMES.

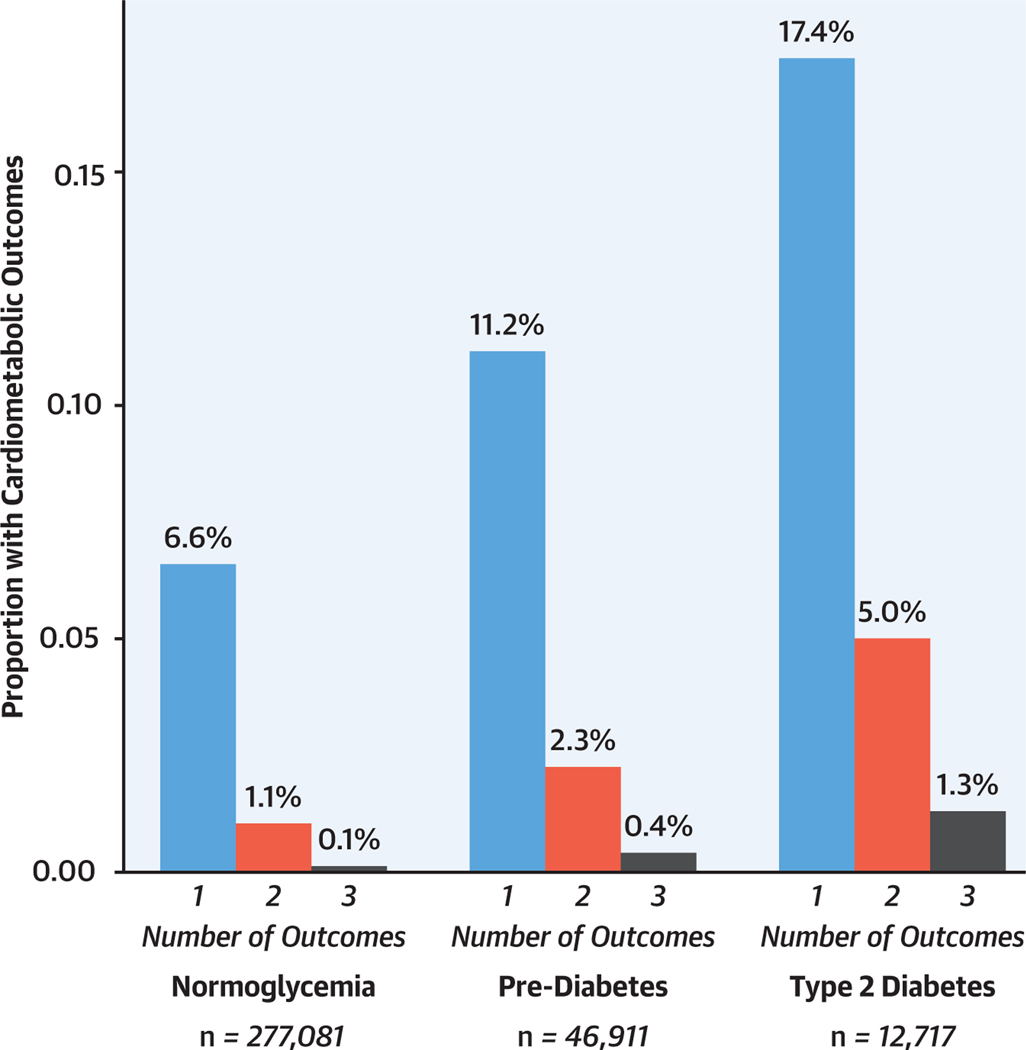

Overall, ≥1 outcome (ASCVD, CKD, and/or heart failure) occurred in 21,769 (7.9%) of individuals with normoglycemia, 6,476 (13.8%) with prediabetes, and 3,017 (23.7%) with T2D during the follow-up period (Figure 1). Case counts are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. ASCVD was the most frequent outcome, occurring in 15,856 cases (5.7%) with normoglycemia, 4,681 (10.0%) with prediabetes, and 2,138 (16.8%) with T2D. Among individuals with incident ASCVD, CAD represented the most frequent diagnosis and was diagnosed in 84.1% (Supplemental Table 2). CKD was diagnosed in 5,473 individuals (2.0%) with normoglycemia, 1,868 (4.0%) with prediabetes, and 1,181 (9.3%) with T2D, and heart failure was diagnosed in 4,207 (1.5%) with normoglycemia, 1,354 (2.9%) with prediabetes, and 660 (5.2%) with T2D (Table 2).

FIGURE 1. Proportion of the Study Sample With ≥1 Primary Study Outcome.

One or more different primary study outcomes (incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or heart failure) occurred in 21,769 (7.9%) individuals with normoglycemia, 6,476 (13.8%) with prediabetes, and 3,017 (23.7%) with type 2 diabetes over a median follow-up period of 11.1 years.

TABLE 2.

Cumulative Incidence and Incidence Rates for Primary Outcomes

| Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease |

Chronic Kidney Disease |

Heart Failure |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. at Risk | Cumulative Incidence (%) | No. of Events/ Person-Years | IR per 1,000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Cumulative Incidence (%) | No. of Events/ Person-Years | IR per 1,000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Cumulative Incidence (%) | No. of Events/ Person-Years | IR per 1,000 Person-Years (95% CI) | |

| Normoglycemia | 277,081 | 5.7 | 15,856/3,003,056 | 5.28(5.20–5.36) | 2.0 | 5,473/3,064,907 | 1.79(1.74–1.83) | 1.5 | 4,207/3,066,510 | 1.37(1.33–1.41) |

| Prediabetes | 46,911 | 10.0 | 4,681/495,890 | 9.44(9.17–9.71) | 4.0 | 1,868/513,733 | 3.64(3.47–3.80) | 2.9 | 1,354/514,941 | 2.63(2.49–2.77) |

| Prediabetes without progression to type 2 diabetes before event | 46,109 | 9.0 | 4,149/488,730 | 8.49(8.23–8.75) | 3.4 | 1,582/505,579 | 3.13(2.97–3.28) | 2.5 | 1,163/506,509 | 2.30(2.16–2.43) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 12,717 | 16.8 | 2,138/129,488 | 16.51(15.81–17.21) | 9.3 | 1,181/136,348 | 8.66(8.17–9.16) | 5.2 | 660/138,223 | 4.77(4.41–5.14) |

CI = confidence interval; IR = incidence rate.

Overall, 6,589 of 46,911 individuals (14.0%) with prediabetes progressed to T2D during the follow-up period. Among 6,476 individuals with prediabetes who developed ≥1 incident outcome, 1,930 (29.8%) progressed to T2D during follow-up, and only 802 (12.4%) developed T2D prior to an incident diagnosis.

In time-to-event models adjusted for age, sex, and race, prediabetes vs normoglycemia was associated with increased risk of ASCVD (HR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.39–1.49; P < 0.001), CKD (HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.40–1.56; P < 0.001) and heart failure (HR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.38–1.56; P < 0.001). After complete covariate adjustment, pre-diabetes remained independently associated with ASCVD (HR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.08–1.15; P < 0.001) and CKD (HR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.02–1.14; P = 0.009) and nominally significantly associated with heart failure (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.01–1.14; P = 0.03). As expected, T2D was independently associated with all outcomes (Table 3). Prediabetes, T2D, and each unit change in HbA1c appeared to associate most strongly with peripheral artery disease among ASCVD subtypes (Supplemental Table 3). In models stratified by White vs non-White race/ethnicity (Supplemental Table 4), associations between prediabetes and outcomes were numerically larger and significant only in White individuals, although estimates did not differ statistically between White and non-White subjects (Pheterogeneity > 0.05 for all).

TABLE 3.

Adjusted HRs for Primary Outcomes

| Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease |

Chronic Kidney Disease |

Heart Failure |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|

| Baseline Glycemic Status | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) |

| Normoglycemia | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Prediabetes | 1.44 (1.39–1.49)* | 1.11 (1.08–1.15)* | 1.48 (1.40–1.56)* | 1.08 (1.02–1.14)† | 1.46 (1.38–1.56)* | 1.07 (1.01–1.14)‡ |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2.25 (2.15–2.36)* | 1.44 (1.37–1.51)* | 3.60 (3.37–3.84)* | 1.57 (1.46–1.69)* | 2.48 (2.28–2.69)* | 1.25 (1.14–1.37)* |

| HbA1c, per % increase | ||||||

| All subjects | 1.36 (1.34–1.38)* | 1.13 (1.11–1.15)* | 1.50 (1.47–1.53)* | 1.13 (1.10–1.16)* | 1.41 (1.38–1.45)* | 1.12 (1.08–1.15)* |

| Subjects without T2D | 1.70 (1.63–1.77)* | 1.16 (1.12–1.21)* | 1.70 (1.59–1.82)* | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.62 (1.50–1.75)* | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) |

| HbA1c | ||||||

| <5.0% | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 5.0%-<5.4% | 1.11 (1.06–1.17)* | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.95 (0.87–1.05) |

| 5.4%-<5.8% | 1.34 (1.27–1.41)* | 1.08 (1.03–1.14)† | 1.21 (1.11–1.32)* | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | 1.15 (1.04–1.27)† | 0.95 (0.86–1.05) |

| 5.8%-<6.2% | 1.77 (1.67–1.87)* | 1.19 (1.12–1.27)* | 1.69 (1.53–1.87)* | 1.07 (0.97–1.18) | 1.56 (1.40–1.75)* | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) |

| 6.2%-<6.6% | 2.23 (2.05–2.42)* | 1.29 (1.19–1.41)* | 2.72 (2.40–3.08)* | 1.26 (1.10–1.43)* | 2.08 (1.79–2.42)* | 1.04 (0.89–1.21) |

| 6.6%-<7.0% | 2.51 (2.27–2.78)* | 1.40 (1.26–1.55)* | 3.43 (2.96–3.97)* | 1.35 (1.16–1.57)* | 2.15 (1.77–2.60)* | 0.98 (0.81–1.20) |

| ≥7.0% | 2.97 (2.76–3.20)* | 1.51 (1.39–1.64)* | 4.28 (3.82–4.80)* | 1.44 (1.27–1.63)* | 3.16 (2.76–3.61)* | 1.30 (1.12–1.50)* |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, age2, sex, and race. Model 2: Adjusted for age, age2, sex, race, Townsend deprivation index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, vegetable and fresh fruit intake, history of cancer, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, cholesterol-lowering medication use, body mass index, insulin use (HbA1c exposure models only), C-reactive protein, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.017.

P < 0.05.

HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; ref = reference; T2D = type 2 diabetes.

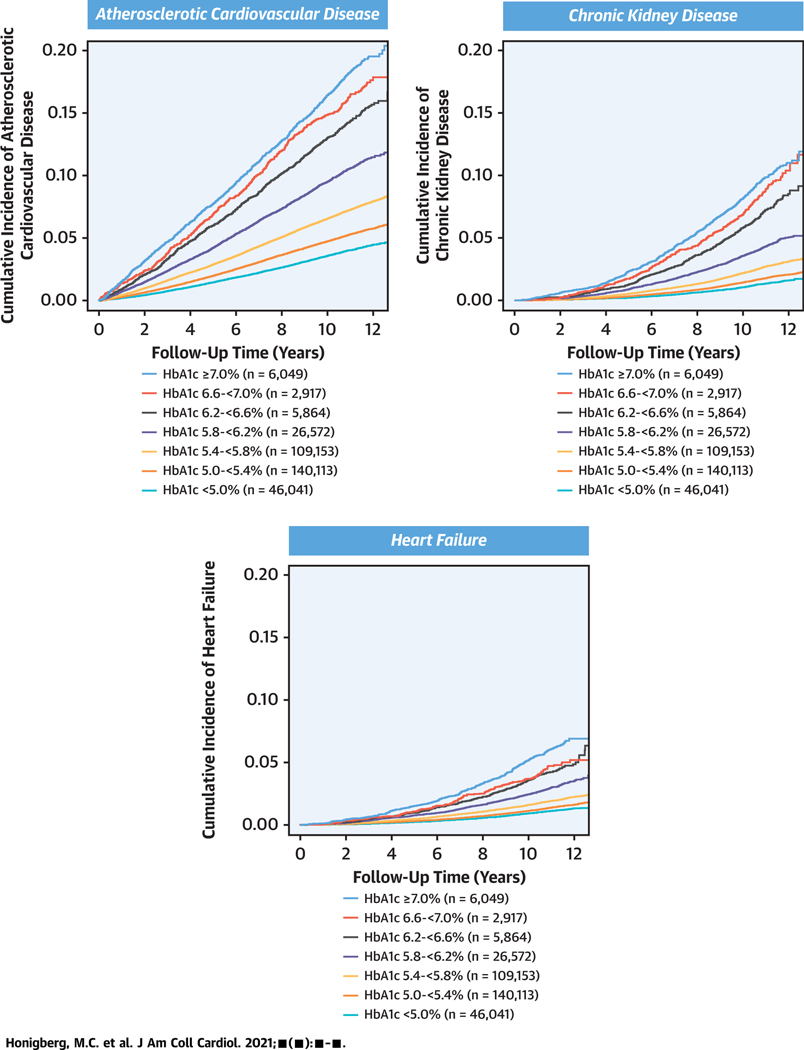

In cubic spline models, the risk associated with HbA1c appeared to nadir at an HbA1c level of approximately 5.0% (Supplemental Figure 2). A substantial gradient of risk was evident for all outcomes across HbA1c levels even in the prediabetic range and below (Central Illustration). In demographic-adjusted models, compared with HbA1c <5.0%, risks were increased for ASCVD above HbA1c 5.0% and for CKD and heart failure above HbA1c 5.4%; after full covariate adjustment, risks were independently increased for ASCVD above HbA1c 5.4%, for CKD above HbA1c 6.2%, and for heart failure above HbA1c 7.0% (Table 3). The risk of ASCVD and heart failure varied by 3-fold and of CKD by 4-fold between HbA1c <5.0% and HbA1c ≥7.0%.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Incident Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease, Heart Failure, and Chronic Kidney Disease by Baseline Hemoglobin A1c Level.

A 3- to 4-fold gradient of cardiovascular and kidney disease risk was observed between HbA1c ≥7.0% and HbA1c <5.0%. HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c

In sensitivity analyses incorporating incident T2D as a time-varying covariate (Supplemental Table 5), prediabetes and T2D remained significantly associated with incident ASCVD in fully adjusted models (prediabetes: HR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.04–1.11; P < 0.001; T2D: HR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.24–1.38; P < 0.001), and risks of incident ASCVD were independently increased above HbA1c 5.4%. Both prediabetes and T2D were associated with heart failure in sparsely adjusted models, but these associations did not persist after full covariate adjustment (Supplemental Table 5).

In addition, death occurred in 12,170 of individuals (4.4%) with normoglycemia, 3,372 (7.2%) with prediabetes, and 1,320 (10.4%) with T2D. Prediabetes vs normoglycemia was independently associated with all-cause mortality (HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.05–1.14; P < 0.001). After full covariate adjustment, the risk of all-cause mortality appeared to increase beginning at HbA1c levels above 6.2% (Supplemental Table 3).

POPULATION ATTRIBUTABLE RISK.

The population attributable risk proportion was larger for baseline prediabetes vs T2D status for ASCVD (8.1% vs 5.9%, respectively) and heart failure (9.9% vs 7.1%) but not CKD (9.8% vs 10.5%). After excluding individuals without T2D at baseline who developed T2D prior to a study endpoint, the population attributable risk proportion remained similar for prediabetes vs T2D for ASCVD (6.0% vs 6.2%) and heart failure (6.8% vs 7.6%). In addition, a greater population attributable risk proportion was observed for baseline prediabetes vs T2D across ASCVD subtypes (CAD: 7.9% vs 5.9%; ischemic stroke: 6.8% vs 5.3%; peripheral artery disease: 12.8% vs 9.3%).

ACCUMULATION OF MULTIMORBIDITY BY GLYCEMIC STATUS.

Individuals with prediabetes and T2D were more likely than were those with normoglycemia to develop multiple outcomes during follow-up (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1). Overall, 3,373 subjects (1.2%) with normoglycemia, 1,243 (2.6%) with prediabetes, and 799 (6.3%) with T2D developed ≥2 primary outcomes. In demographic-adjusted models, prediabetes was associated with 1.7-fold risk of multiple diagnoses vs no diagnosis (odds ratio [OR]: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.59–1.82; P < 0.001), and T2D with 4.3-fold risk (OR: 4.26; 95% CI: 3.93–4.64; P < 0.001). After full covariate adjustment, both prediabetes and T2D remained significant associated with increased odds of multiple diagnoses vs no incident diagnosis (prediabetes: OR: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.08–1.25; P < 0.001; T2D: OR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.70–2.05; P < 0.001).

Time from study enrollment to first outcome diagnosis was shorter in those with T2D vs prediabetes vs normoglycemia (Table 4). Among the study outcomes, time to first diagnosis was shortest for ASCVD and longest for CKD across glycemic categories. Among those who developed ≥2 outcomes, median time from first to second outcome diagnosis was ≤1.3 years irrespective of the initial diagnosis (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Development of First and Second Study Outcomes by Baseline Glycemic Status

| Baseline Glycemic Status | N | First Outcome | n (%) | Time to First Diagnosis (y), Median (IQR) | Second Outcome, n (% With First Outcome) | Time to Second Diagnosis, Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NormogLycemia | 277,081 | ASCVD | 15,119 (5.5) | 6.1 (3.4, 8.5) | 2,361 (15.6) | 0.1 (0, 2.8) |

| CKD | 4,396 (1.6) | 8.1 (5.6, 9.8) | 514 (11.7) | 0.9 (0.1, 2.8) | ||

| Heart failure | 2,254 (0.8) | 7.5 (4.7, 9.5) | 498 (22.1) | 1.0 (0.2, 2.8) | ||

| Prediabetes | 46,911 | ASCVD | 4,396 (9.4) | 5.8 (3.1, 8.4) | 856 (19.5) | 0.5 (0, 3.4) |

| CKD | 1,416 (3.0) | 7.8 (5.3, 9.6) | 211 (14.9) | 1.3 (0.3, 3.3) | ||

| Heart failure | 664 (1.4) | 7.2 (4.3, 9.4) | 176 (26.5) | 1.0 (0.3, 3.0) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes 12,717 | 12,717 | ASCVD | 1,937 (15.2) | 5.6 (2.9, 8.3) | 501 (25.6) | 0.7 (0, 3.4) |

| CKD | 840 (6.6) | 7.2 (5.0, 9.4) | 183 (21.8) | 0.9 (0.1, 2.6) | ||

| Heart failure | 240 (1.9) | 6.9 (4.0, 9.2) | 115 (47.9) | 0.7 (0.1,1.9) | ||

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; IQR = interquartile range.

Among subjects who developed incident ASCVD as their first study outcome, in time-to-event models with follow-up beginning at ASCVD diagnosis, T2D was independently associated with subsequent diagnoses of CKD (HR: 1.59; 95% CI: 1.38–1.84; P < 0.001) and heart failure (HR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.01–1.37; P = 0.005). Among those with an initial diagnosis of CKD, T2D was independently associated with subsequent development of heart failure (HR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.16–1.94; P = 0.002). Similarly, among those with a first diagnosis of heart failure, T2D was independently associated with nearly 2-fold risk of subsequent diagnoses of ASCVD and CKD (Supplemental Table 6).

PREDICTORS OF RISK BY GLYCEMIA STATUS.

Finally, we tested interactions between prediabetes and T2D status and covariates, as well as between HbA1c and covariates, for each primary outcome in fully adjusted models (Supplemental Table 7). The associations of current smoking, adjusted SBP, and adjusted non-HDL cholesterol with ASCVD were relatively stronger at lower HbA1c levels. In addition, the association of C-reactive protein with outcomes was relatively stronger at lower HbA1c levels across all 3 study outcomes (Supplemental Table 7).

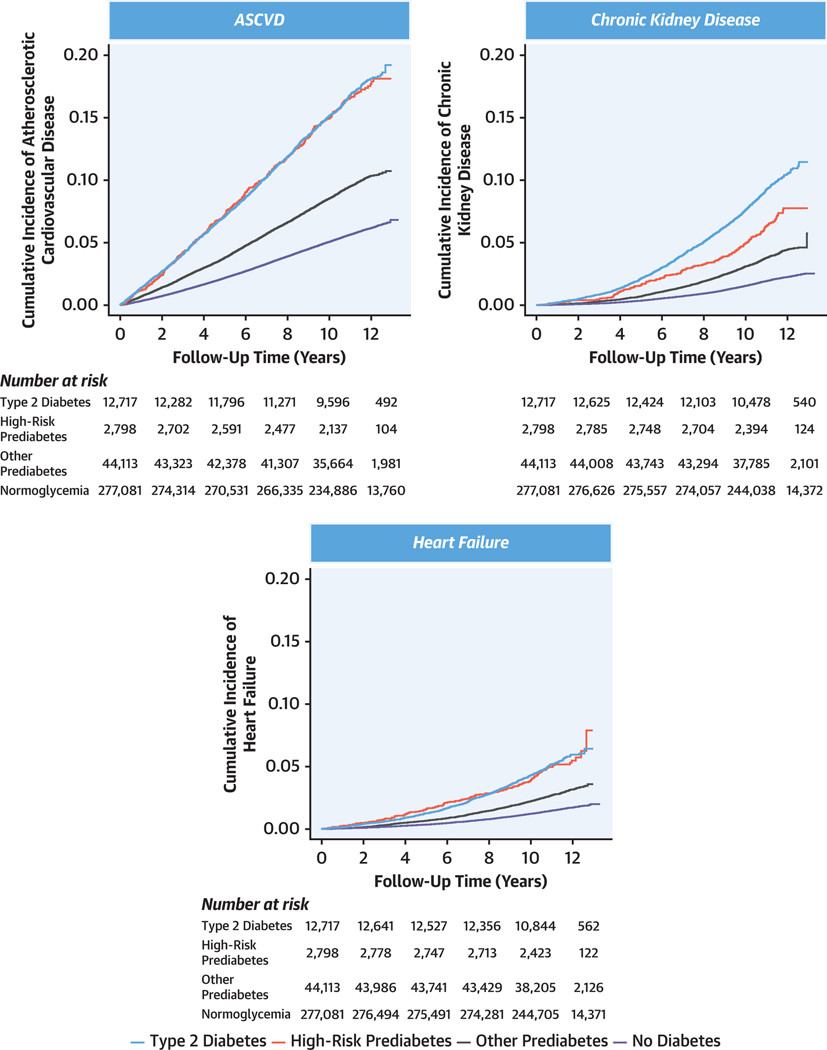

In post hoc analyses, we tested whether key variables may identify a high-risk subgroup of individuals with prediabetes. Based on the results of interaction analyses, high-risk prediabetes was defined as individuals with prediabetes who were current or former smokers and who had medication-adjusted SBP, medication-adjusted non-HDL cholesterol, and C-reactive protein each in the top tertile of the study sample (corresponding to adjusted SBP ≥148 mm Hg [ie, ≥133 mm Hg for individuals on antihypertensive therapy], adjusted non-HDL cholesterol ≥189.5 mg/dL [ie, ≥128.9 mg/dL for those on cholesterol-lowering therapy], and C-reactive protein ≥2.07 mg/L). This designation identified 2,798 of 46,911 individuals (6.0%) with prediabetes as having high-risk prediabetes.

Cumulative incidence of ≥1 primary study outcome was 3,017 of 12,717 individuals (23.7%) among individuals with T2D, 633 of 2,798 (22.6%) among those with high-risk prediabetes, and 5,843 of 44,113 (13.2%) among those with other prediabetes. Among 633 individuals with high-risk prediabetes who developed ≥1 incident outcome, only 208 (32.9%) progressed to T2D during follow-up. Cumulative incidence was similar in high-risk prediabetes vs T2D for ASCVD (16.7% vs 16.8%, respectively) and heart failure (5.0% vs 5.2%), but lower for high-risk prediabetes vs T2D for CKD (6.5% vs 9.3%) (Figure 2). Individuals with high-risk vs other prediabetes had nearly 2-fold risk of outcomes overall (ASCVD: 16.7% vs 9.6%; P< 0.001; CKD: 6.5% vs 3.8%; P < 0.001; heart failure: 5.0% vs 2.8%; P < 0.001) and in both men and women separately (Supplemental Figure 3).

FIGURE 2. Incident ASCVD, Heart Failure, and CKD by Baseline Diabetes Status.

The “high-risk prediabetes” category was defined as individuals with prediabetes who were current or former smokers and who had medication-adjusted systolic blood pressure, medication-adjusted non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and C-reactive protein each in the top tertile of the study sample (corresponding to adjusted systolic blood pressure ≥148 mm Hg [ie, ≥133 mm Hg for individuals on antihypertensive therapy], adjusted non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥189.5 mg/dL [ie, ≥128.9 mg/dL for those on cholesterol-lowering therapy], and C-reactive protein ≥2.07 mg/L). All other individuals with prediabetes were classified as belonging to the “other prediabetes” category. ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease.

DISCUSSION

In a large population-based cohort of individuals without established ASCVD, CKD, or heart failure, a substantial gradient of cardiovascular and kidney disease risk was evident across HbA1c levels including those in the prediabetic range, with a nadir of risk observed in individuals with HbA1c <5.0%. Most incident disease occurred in individuals with HbA1c below the threshold for diabetes, and the population attributable risks for the outcomes of ASCVD and heart failure were greater for prediabetes vs T2D. More than two-thirds of individuals with prediabetes who developed cardiovascular and kidney disease did not progress to T2D over a median 11 years of follow-up. Subjects with prediabetes plus other specific CVD risk factors had similar absolute risks as did those with T2D, identifying a high-risk subgroup of prediabetic individuals.

Our results corroborate prior work suggesting that prediabetes is independently associated with ASCVD (12,13,22,23) and all-cause mortality (13) and extend these findings to include ASCVD subtypes. In addition, prior data on the association of prediabetes with incident CKD and heart failure are sparse and without clear evidence of association (24). Here, we demonstrate associations of HbA1c levels <6.5% with incident CKD and heart failure.

These findings may have implications for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and kidney disease in individuals with dysglycemia. First, HbA1c may be better considered as a continuous measure of risk, rather than dichotomized as ≥6.5% vs <6.5%, even below diagnostic thresholds for T2D. In our sample, the risk of ASCVD and heart failure varied by 3-fold and of CKD by 4-fold between HbA1c <5.0% and HbA1c ≥7.0%. Prior studies have suggested that CAD risks vary continuously below thresholds for T2D with progressively lower risks reported in association with lower HbA1c values (11,25). The present study highlights the substantial gradient of ASCVD risk present across and below the prediabetic range of HbA1c and extends this finding to CKD and heart failure. Future studies in higher-risk populations with a greater number of cardio-renal-metabolic events are needed to corroborate specific glycemic thresholds above which the risk of these events is enhanced.

Second, the development of a first cardiovascular or kidney event heralded substantially increased risk of accumulating multimorbidity, particularly among those with T2D at baseline. Moreover, once a first event occurred, the time to a second event in affected individuals was short irrespective of baseline glycemic status, with many experiencing a second event within the subsequent year. These findings highlight the importance of both comprehensive primary prevention as well as rapid implementation of secondary prevention measures once cardiovascular or kidney disease is diagnosed, including consideration of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1RA in eligible at-risk individuals.

Third, prediabetes was associated with elevated cardiovascular and kidney disease risk even before progression to T2D, bolstering evidence that prediabetes represents a relevant entity among middle-aged individuals. In a recent analysis from the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study of individuals 71 to 90 years of age, among those with HbA1c 5.7% to 6.4% at baseline, 9% progressed to diabetes and 19% died over median 5 years of follow-up, raising the question of whether prediabetes represents a useful diagnosis in an elderly population (26). Among individuals with prediabetes in our middle-aged cohort (40–69 years of age at enrollment), only 14% progressed to T2D and 7.2% died during follow-up; cardiovascular and kidney risks were appreciably elevated in the remaining ∼80% of participants who did not experience glycemic progression to T2D. Similar to a prior UK Biobank–based analysis that defined prediabetes as HbA1c 6.0% to 6.4% and examined ASCVD composite outcomes (12), individuals with HbA1c in the prediabetic range had a worse overall cardiometabolic risk profile compared with individuals without prediabetes. These findings lend support to the notion that prevention strategies targeting prediabetic individuals should include comprehensive and aggressive CVD risk factor modification, not simply interventions to prevent glycemic progression from prediabetes to T2D (12).

Fourth, cardiovascular and kidney outcomes trials may be feasible in high-risk subsets of prediabetic individuals. In our sample, subjects with prediabetes who possessed data-defined high-risk features (current or former smokers and adjusted blood pressure, cholesterol, and C-reactive protein in the upper third of the study population) had nearly superimposable cumulative incidence of ASCVD and heart failure compared with individuals with T2D and roughly 2-fold incidence of all study outcomes vs other prediabetic individuals. These well-established risk markers that assay multiple nonglycemic pathophysiologic processes may be especially prognostic at the lower end of the glycemic spectrum. Guidelines now advocate use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1RA in patients with established CVD or at high CVD risk for risk reduction irrespective of glycemic targets (8,27), and mounting evidence suggests these medication classes exert favorable cardio-renal-metabolic effects independent of glycemia and in nondiabetic and prediabetic individuals (28–30). The GLP-1RA semaglutide is under study for secondary ASCVD prevention in individuals with HbA1c <6.5% (NCT03574597), which is expected to clarify treatment effects of GLP-1RA in individuals the lower end of the glycemic spectrum. In addition, metformin is currently under study for secondary ASCVD prevention in individuals with prediabetes (NCT02915198). Whether metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, and/or GLP-1RA confer incremental cardiovascular and kidney risk-reducing benefit in high-risk individuals with prediabetes in the primary prevention setting on top of standard CVD prevention approaches warrants prospective assessment in randomized trials.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

Strengths of this study include comprehensive and uniform baseline phenotyping, including measurement of HbA1c, in a uniquely large cohort with ability to ascertain diverse incident outcomes over median follow-up of over 11 years. This work should also be interpreted within the context of some limitations. First, the UK Biobank is on average healthier than the broader UK population (31). Low prevalence of prediabetes and T2D likely reflect this healthy participant bias, which may result in underestimation of population attributable risks associated with dysglycemia. Second, we lacked adequate power to test glycemic relationships in specific non-White subgroups, and the magnitude of observed associations may not generalize to diverse populations. Although HbA1c is endorsed by the American Diabetes Association (18) and commonly used to assess dysglycemia in contemporary practice, slightly higher HbA1c levels have been observed for given glucose concentrations in Black individuals (32), and dedicated studies of cardio-metabolic risk across the glycemic spectrum in non-White populations are needed. Third, HbA1c was measured in a standardized fashion at study enrollment, but although longitudinal follow-up captured incident T2D, follow-up glycemic measures were not routinely available to carefully dissect glycemic regression, stability, or progression. Fourth, because of phenotyping limitations, we were unable to test the association of glycemic status with specific heart failure subtypes (eg, ischemic vs nonischemic cardiomyopathy, preserved vs reduced ejection fraction). Finally, clinical parameters and biomarkers used to define high-risk prediabetes were determined post hoc and require external validation to corroborate their utility.

CONCLUSIONS

Most cardiovascular and kidney disease occurs in individuals with HbA1c levels below the threshold for diabetes. A substantial gradient of cardiovascular and kidney disease risk is evident across HbA1c levels including those in the prediabetic range. Furthermore, high-risk individuals with prediabetes have similar cardiovascular disease risk as individuals with T2D do. These findings collectively highlight the need to design specific cardiovascular and kidney risk-reduction strategies across the glycemic spectrum, including below thresholds used to define diabetes.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE:

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes and are associated with a substantial gradient of cardiovascular and renal risk across HbA1c levels below the threshold for diabetes.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

Clinical trials focusing on cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in high-risk patients with prediabetes could lead to risk-reduction strategies that apply across the glycemic spectrum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was conducted under UK Biobank application number 7089.

FUNDING SUPPORT AND AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

Dr Honigberg is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32HL094301-07). Dr Natarajan is supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL142711, R01HL148050, R01HL148565, R01HL151283), Fondation Leducq (TNE-18CVD04), and a Hassenfeld Scholar Award from Massachusetts General Hospital; has received grant support from Amgen, Apple, Boston Scientific, and Novartis; has received personal fees from Apple, Blackstone Life Sciences, Genentech, and Novartis; and Dr Natarajan’s spouse has been employed by Vertex, all unrelated to the present work. Dr Vaduganathan has received research grant support or served on advisory boards for American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer AG, Baxter Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Relypsa; has had speaking engagements with Novartis and Roche Diagnostics; and has participated on clinical endpoint committees for studies sponsored by Galmed and Novartis.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- GLP-1RA

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- IQR

interquartile range

- OR

odds ratio

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SGLT2

sodium glucose cotransporter 2

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

APPENDIX For the supplemental appendix, figures, and tables, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dinesh Shah A, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of a wide range of cardiovascular diseases: a cohort study in 1–9 million people. Lancet 2015;385 suppl 1:S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, et al. Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA 2016;316(6): 602–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAllister DA, Read SH, Kerssens J, et al. Incidence of hospitalization for heart failure and casefatality among 3.25 million people with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2018; 138(24):2774–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawshani A, Franzén S, Eliasson B, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular disease in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;376(15):1407–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawshani A, Franzén S, Sattar N, et al. Risk factors, mortality, and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(7):633–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg DD, Wiviott SD, Scirica BM, et al. Heart failure risk stratification and efficacy of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2019; 140(19):1569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, et al. Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;24(2):302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalyani RR. Glucose-lowering drugs to reduce cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021;384(13):1248–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullard KM, Saydah SH, Imperatore G, et al. Secular changes in U.S. prediabetes prevalence defined by hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999–2010. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(8):2286–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andes LJ, Cheng YJ, Rolka DB, Gregg EW, Imperatore G. Prevalence of prediabetes among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2005–2016. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174(2):e194498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvin E, Coresh J, Golden SH, Brancati FL, Folsom AR, Steffes MW. Glycemic control and coronary heart disease risk in persons with and without diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(16):1910–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welsh C, Welsh P, Celis-Morales CA, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, prediabetes, and the links to cardiovascular disease: data from UK Biobank. Diabetes Care 2020;43(2):440–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai X, Zhang Y, Li M, et al. Association between prediabetes and risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: updated meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvin E, Lazo M, Chen Y, et al. Diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, and incidence of subclinical myocardial damage. Circulation 2014;130(16):1374–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skali H, Shah A, Gupta DK, et al. Cardiac structure and function across the glycemic spectrum in elderly men and women free of prevalent heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk In the Community study. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8(3):448–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piller C The war on ‘prediabetes’ could be a boon for pharma—but is it good medicine?. March 7, 2019. Science Magazine, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/03/war-prediabetes-could-be-boon-pharma-it-good-medicine. Accessed April 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 2018;562(7726):203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association. 3. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021;44 suppl 1:S34–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott P, Peakman TC, UK Biobank. The UK Biobank sample handling and storage protocol for the collection, processing and archiving of human blood and urine. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37(2): 234–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honigberg MC, Chaffin M, Aragam K, et al. Genetic variation in cardiometabolic traits and medication targets and the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Circulation 2020;142(7): 711–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bick AG, Pirruccello JP, Griffin GK, et al. Genetic interleukin 6 signaling deficiency attenuates cardiovascular risk in clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation 2020;141(2):124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong M, Woodward M, Peters SAE. Diabetes, glycated hemoglobin, and the risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: a prospective cohort study of the UK Biobank. Diabetes Care 2020;43(9):2050–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HK, Lee JB, Kim SH, et al. Association of prediabetes, defined by fasting glucose, HbA1c only, or combined criteria, with the risk of cardiovascular disease in Koreans. J Diabetes 2016; 8(5):657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvin E, Ning Y, Steffes MW, et al. Glycated hemoglobin and the risk of kidney disease and retinopathy in adults with and without diabetes. Diabetes 2011;60(1):298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Luben R, Welch A, Day N. Association of hemoglobin A1c with cardiovascular disease and mortality in adults: the European prospective investigation into cancer in Norfolk. Ann Intern Med 2004;141(6):413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rooney MR, Rawlings AM, Pankow JS, et al. Risk of progression to diabetes among older adults with prediabetes. JAMA Intern Med 2021;181(4): 511–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43 suppl 1:S111–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. STEP 1 Study Group. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021;384(11):989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with heart failure by baseline diabetes status: results from the EMPEROR-Reduced Trial. Circulation 2021;143(4):337–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheeler DC, Stefánsson BV, Jongs N, et al. DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Effects of dapagliflozin on major adverse kidney and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetic and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: a prespecified analysis from the DAPA-CKD trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021; 9(1):22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fry A, Littlejohns TJ, Sudlow C, et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186(9):1026–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergenstal RM, Gal RL, Connor CG, et al. T1D Exchange Racial Differences Study Group. Racial differences in the relationship of glucose concentrations and hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Intern Med 2017;167(2):95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.