Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate whether total FSH dose was negatively correlated with number of oocytes retrieved in a large data set where previously, a negative correlation between FSH dose and live birth rate was identified.

Methods

Data from 650,637 fresh autologous in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles reported to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology between 2004 and 2012 were included. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine if the relationship between total FSH dose used during ART with number of oocytes retrieved was impacted by the patient’s health prognosis, age, BMI, ovarian stimulation protocol, or infertility diagnosis.

Results

The number of oocytes retrieved was negatively correlated with FSH dose (P < 0.0001). Regardless of patient prognosis, age, BMI, ovarian stimulation protocol, and infertility diagnosis, the highest number of oocytes retrieved was in the 1001–2000 IU FSH group, and was 36–51% lower in the > 5000 IU compared with the optimal, 1001–2000 IU, FSH groups. Overall, ~80% of patients received FSH doses outside of the optimal FSH dose. Moreover, 61% of good prognosis patients (excludes individuals likely prescribed higher FSH doses) received doses exceeding the optimal dose range.

Conclusion

The inverse relationship between FSH dose and the number of oocytes retrieved independent of patient age or health implies that excessive FSH doses during ART may be detrimental to oocyte retrieval.

Keywords: FSH, Oocyte retrieval, Ovarian stimulation

Introduction

Ovarian stimulation during assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles utilizes exogenous gonadotropins to override the mechanism by which a single ovarian follicle completes folliculogenesis. This allows for the retrieval of multiple oocytes which can be used for ART. The total FSH dose administered during ovarian stimulation is dependent on patient characteristics (for example, age and diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve) and responsiveness to FSH. Hence, patients that respond poorly or slowly to ovarian stimulation tend to receive higher doses [1–4]. However, whether increasing FSH dose improves oocyte retrieval has yet to be conclusively demonstrated and was investigated in the current study using the same data set used by Baker et al. (2015) to identify the negative correlation between total FSH dose and live birth rate [5].

Presumably one measure of the efficacy of an FSH dose is the number of oocytes that are recovered during an ART cycle. In terms of the number of oocytes retrieved, very few studies have examined the dose–response relationship to FSH across a range of doses. Whilst there is evidence of a positive dose–response relationship, there is conflicting evidence as to whether the highest doses evaluated in these studies were, in fact, detrimental to oocyte retrieval [6–10]. Comparatively, more studies have assessed the effects of two doses, generally lower compared to a higher dose, on ART outcomes. Results of these studies indicate that high FSH doses are either detrimental to or have no effect on ART outcomes, including the number of oocytes retrieved, fertilization rate, number of embryos produced, embryo quality, blastocyst rate, number of transferrable or frozen embryos, and live birth rate [11–20].

In addition to the number of oocytes retrieved, some studies also report the total number of follicles that develop or the number of mature oocytes retrieved in response to gonadotropin stimulation [9, 14, 15, 19, 21]. This is particularly useful as follicular development and oocyte maturation (including the number of mature oocytes) are considered indices of ovarian function and responses to gonadotropin stimulation. Whilst not available for the current data set, such data could be used to investigate whether excessive FSH doses negatively affect ovarian function. In addition, the mechanisms by which high FSH doses during ovarian stimulation impact ovarian function and subsequently follicular maturation are poorly understood. Data from studies in mice have shown that in vivo, high FSH doses may uncouple the oocyte from the somatic cells of the follicle and in vitro, accelerate nuclear maturation and may induce chromosomal abnormalities [22, 23]. Similarly, bovine studies have shown that using high gonadotropin doses during superovulation was detrimental to ovulatory follicle function, including estradiol production and ovulation rate [24] and decreased oocyte developmental competence resulting in decreased rates of transferrable, high quality, embryos [25] and in a decrease in ovulation rate [26]. These data demonstrate that high gonadotropin doses have a negative impact on follicular maturation and may explain, at least in part, the negative impact of high FSH doses on oocyte retrieval and ART outcomes including fertilization rate, number of embryos produced, embryo quality, blastocyst rate, number of transferrable embryos, and live birth rate.

Other key considerations relating to efficacy of ovarian stimulation include oocyte maturation and quality (reflected in embryo production and the live birth rate), minimizing the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and cost of treatment. Generally, increasing oocyte retrieval rates have been positively associated with improved IVF outcomes (blastocyst formation, pregnancy rates) and live birth rate [27–30]. Based on these data, current ovarian stimulation procedures aim to induce the development of 5–15 oocytes, with low- (< 4 oocytes) and high-(> 15 oocytes) responders predicted to have poorer outcomes [31], in terms of live birth rate and OHSS, respectively [32]. A number of studies have recommended using 150 IU as the daily FSH dose to achieve optimal oocyte retrieval and maintain high live birth rates [13, 17, 18].

Previous analysis of the same data set of > 650,000 ART cycles used herein concluded that high FSH doses were negatively correlated to live birth rate and within FSH dose categories, the number of oocytes retrieved was positively correlated with live birth rate irrespective of age, BMI, and patient diagnoses (diminished ovarian reserve or ovulatory disorder) [5]. It was also noted in this previous publication that daily FSH dose ranged from 25 to 450 IU and total FSH dose administered per cycle ranged from 75 to 18,000 IU indicating that the daily and the total FSH dose varied substantially between cycles [5]. However, the relationship between FSH dose and the number of oocytes retrieved was not evaluated in the previous study [5]. Given that a key outcome of ovarian stimulation is to increase the number of oocytes retrieved in an ART cycle, the study reported herein was designed to investigate the hypothesis that total FSH dose is also negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved using this same data set. A wide range of factors will influence a patient’s response to ovarian stimulation and likewise, a range of factors also influence a clinician’s choice of FSH dose. The purpose of this analysis was not to identify all factors that contribute to these, as this is not possible with the current data set. Instead, using this data set, arguably one of the largest currently available, consisting of an unselected population and patients with different characteristics (for example, age, BMI), diagnoses (for example, diminished ovarian reserve, PCOS) known to affect the number of oocytes retrieved and who were treated with a wide range of doses, we investigated the aforementioned hypothesis.

Methodology

Data were collected and verified by the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) and reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in compliance with the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (Public Law 102-493). The data in the SART CORS include data from > 90% of clinics providing IVF in the United States and are validated annually with some clinics having on-site visits for chart review based on an algorithm for clinic selection. During each clinic visit, data reported by the clinic were compared with information recorded in patients’ charts. Ten out of 11 data fields selected for validation were found to have discrepancy rates of ≤ 5% [33]. Only data from 650,637 fresh, autologous IVF cycles reported between 2004 and 2012 were included in this study. In the current study, the following data were excluded from statistical analyses: ART cycles where no oocytes were retrieved, ART cycles where ovulation was induced using oral medications, and ART cycles where the number of oocytes retrieved was > 1000. These discrepancies were likely due to data entry errors. Logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between FSH dose (< 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000, 3001–4000, 4001–5000, and > 5000 IU) with number of oocytes retrieved during each ART cycle for patients within the following categories: health prognosis (good or negative), age (< 35, 35–39, ≥ 40 years), BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, and ≥ 30), ovarian stimulation protocol (agonist suppression, agonist flare, antagonist suppression), and infertility diagnosis (endometriosis, PCOS, diminished ovarian reserve, tubal disease, unexplained infertility, and other reasons for ART). As noted previously, FSH dose refers to the total gonadotropin dose as reported to SART CORS and includes the total dose of FSH from FSH-only and human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) preparations [5] and does not include any luteinizing hormone activity, if administered. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) concentrations were first included in the SART CORS database from 2012 (the final year’s data included in this analysis) and subsequently have been used to inform FSH dose selection in patients. Due to the limited serum AMH concentration available for the data set, it was not included in the current analysis.

Good prognosis patients were defined as patients < 35 years of age with a body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2 and no diagnosis of either diminished ovarian reserve or endometriosis. This category excluded patients with the most significant confounding characteristics or diagnoses that would account for being administered higher FSH doses based on the information available in the SART CORS database (mean total FSH dose: 2551 ± 3 IU). In contrast, the negative prognosis category included patients with one or more of the following characteristics and diagnoses: patient age of ≥ 35 years, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, diminished ovarian reserve, or endometriosis. By comparison, this category included patients who were more likely to be prescribed high FSH doses (mean total FSH dose: 3778 ± 3 IU). The rationale for examining the relationship between FSH dose and oocyte retrieval within different categories was that patient characteristics (for example, patient age and BMI), type of ovarian stimulation protocol used, and infertility diagnoses (for example, diminished ovarian reserve) can potentially affect response to ovarian stimulation and choice of dose.

Differences between the proportions of patients in each FSH dose and patient prognosis category were analyzed using chi-square tests. The FSH dose range with the highest number of oocytes retrieved was compared to the highest FSH dose range, to determine the proportional decrease in oocyte retrieval. All analyses were conducted in SAS (9.4). The study was previously approved by the Institutional Review Board at Michigan State University [5].

Results

The proportion of patients treated with each FSH dose range is included in Table 1 and patient characteristics and diagnoses for the overall, good and negative prognosis analyses is included Table 2. As expected, the proportion of patients receiving the three highest doses was higher in the negative, compared to the good prognosis patients (P < 0.0001; Table 1), and increased with age (P < 0.0001; Table 1). Likewise, the proportion of patients with each diagnosis varied in ways that were expected. For example, ~50% of patients in the good prognosis data set had a diagnosis of male factor infertility and/or unexplained infertility (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the proportion of ART cycles categorized by FSH dose (IU) range for each analysis conducted

| FSH dose (IU) | Proportion of patients (%) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Good prognosis | Negative prognosis | < 35 years | 35–39 years | ≥ 40 years | BMI < 18.5 | BMI 18.5–24.9 | BMI 25.0–29.9 | BMI > 30 | Agonist suppression | Agonist flare | Antagonist suppression | Endometriosis | PCOS | Diminshed ovarian reserve | Tubal disease | Unexplained infertility | Other reason for ART | |

| < 1000 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.1 |

| 1001–2000 | 19.8 | 34.4 | 12.9 | 30.8 | 13.7 | 5.9 | 23.4 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 16.8 | 26.9 | 6.2 | 14.8 | 17.4 | 34.3 | 5.7 | 18.8 | 20.9 | 16.6 |

| 2001–3000 | 27.4 | 33.6 | 21.9 | 32.9 | 26.5 | 16.5 | 25.3 | 26.8 | 27.5 | 28.6 | 32.5 | 15.7 | 24.4 | 28.3 | 29.6 | 15.0 | 29.2 | 29.9 | 25.5 |

| 3001–4000 | 17.3 | 13.5 | 21.7 | 14.6 | 19.6 | 19.2 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 16.1 | 19.8 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 13.7 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 17.7 | 18.5 |

| 4001–5000 | 15.6 | 7.9 | 19.3 | 9.6 | 18.6 | 24.0 | 14.7 | 15.0 | 15.5 | 16.2 | 11.4 | 25.0 | 18.3 | 16.4 | 8.9 | 24.3 | 15.7 | 14.3 | 17.5 |

| > 5000 | 16.9 | 5.4 | 22.3 | 7.8 | 19.5 | 32.8 | 15.6 | 16.5 | 17.4 | 18.5 | 9.7 | 31.4 | 21.9 | 17.4 | 8.0 | 35.4 | 15.9 | 14.3 | 18.9 |

| No. of cycles | 650,637 | 206,248 | 444,389 | 288,583 | 236,743 | 125,311 | 9761 | 191,120 | 79,965 | 61,614 | 316,242 | 80,837 | 241,901 | 78,007 | 95,800 | 128,927 | 112,738 | 88,619 | 85,060 |

The total number of ART cycles for each analysis is included in the last row

Table 2.

Patient characteristics including age, BMI, and percentage of cycles with each diagnosis for the overall, good and negative prognosis analyses

| All cycles | Good prognosis | Negative prognosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean patient age in years (range) |

35.6 (18.2, 57.6) |

31.2 (18.2, 34.9) |

37.6 (18.7, 57.6) |

| Mean BMI (range) |

25.4 (14.1, 68.4) |

23.2 (14.1, 29.9) |

26.3 (14.1, 68.4) |

| Diagnoses | Proportion of patients (%) | ||

| Male factor | 38.1 | 45.9 | 34.5 |

| Endometriosis | 12.0 | NA | 17.6 |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 14.7 | 22.2 | 11.2 |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 19.8 | NA | 29.0 |

| All tubal disease | 17.3 | 17.0 | 17.5 |

| Uterine abnormality | 4.8 | 3.0 | 5.6 |

| Other | 13.1 | 12.5 | 13.4 |

| Unexplained | 13.6 | 17.5 | 11.8 |

| No. of cycles | 650,637 | 206,248 | 444,389 |

The mean patient age and BMI are included with the range (minimum, maximum) for the appropriate analysis. Likewise, the proportion of cycles including patients with a positive diagnosis for endometriosis, PCOS, diminished ovarian reserve, tubal disease, uterine abnormality, and other reasons for ART and unexplained infertility were calculated for each study population. The total number of ART cycles included for each analysis is included in the last row. Note that column totals are not equivalent to 100% because a patient could have more than one diagnosis recorded. NA not applicable

A negative relationship between the number of oocytes retrieved and FSH dose category (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1 top panel) was identified. The number of oocytes retrieved decreased by 48% from the 1001–2000 to > 5000 IU FSH dose categories and > 80% of patients received doses outside the 1001–2000 dose range (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between total FSH dose (IU) and number of oocytes retrieved in patients undergoing fresh autologous IVF cycles for the overall data set (all patients; top panel) and parsed by patient prognosis (good and negative prognosis; bottom panel). Good prognosis patients were selected based on the following criteria: < 35 years, body mass index < 30 kg/m2, no diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve, or endometriosis. Negative prognosis patients were selected based on the following criteria: either ≥ 35 years and/or body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 and/or diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve, or endometriosis. FSH dose categories included < 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000, 3001–4000, 4001–5000, and > 5000 IU. FSH dose category was significantly negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved in all analyses (P < 0.0001). The figure also depicts (red line and text) the decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the highest (> 5000 IU) FSH dose category compared to the category with the highest number of oocytes retrieved (1001–2000 IU). The number of patients included in each analysis (N =) is depicted on the appropriate graph

A negative relationship (P < 0.0001) existed between the number of oocytes retrieved and FSH dose in patients without (good prognosis, Fig. 1) and with (negative prognosis, Fig. 1) characteristics or diagnoses increasing the likelihood of receiving higher FSH doses. In both analyses, the highest oocyte retrieval was observed in the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose category. The number of oocytes retrieved decreased by 38 and 46% in the > 5000 IU FSH dose category in the good and negative prognosis analyses, respectively (Fig. 1). In spite of the fact that the good prognosis subgroup excluded all patients likely receiving high FSH doses due to patient characteristics or diagnoses, 60% of these patients received doses > 2000 IU FSH (Table 1).

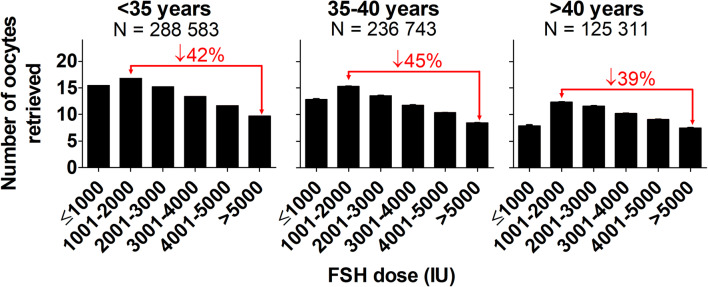

Regardless of patient age category, FSH dose category was negatively correlated (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2) with the number of oocytes retrieved and the highest oocyte retrieval was observed in the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose category. The decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the > 5000 compared to the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose groups was 42, 45, and 39% in the < 35, 35–39, and ≥ 40 year categories, respectively (Fig. 2). The proportion of patients receiving higher doses of FSH also increased with age (P < 0.0001; Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between total FSH dose (IU) and number of oocytes retrieved in patients undergoing fresh autologous IVF cycles, parsed by patient age (< 35 years, 35–40 years, and > 40 years). FSH dose categories included < 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000, 3001–4000, 4001–5000, and > 5000 IU. FSH dose category was significantly negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved in all patient age categories (P < 0.0001). The figure also depicts (red line and text) the decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the highest (> 5000 IU) FSH dose category compared to the category with the highest number of oocytes retrieved (1001–2000 IU). The number of patients included in each analysis (N =) is depicted on the appropriate graph

When ART cycles were stratified into BMI categories (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, > 30), FSH dose was negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved, irrespective of BMI (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). The number of oocytes retrieved decreased by 51, 50, 47, and 40% when patient BMI was < 18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, and > 30, respectively, in the > 5000 compared to the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose categories (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between total FSH dose (IU) and number of oocytes retrieved in patients undergoing fresh autologous IVF cycles, parsed by patient BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, and ≥ 30). FSH dose categories included < 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000, 3001–4000, 4001–5000, and > 5000 IU. FSH dose category was significantly negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved in all patient BMI categories (P < 0.0001). The figure also depicts (red line and text) the decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the highest (> 5000 IU) FSH dose category compared to the category with the highest number of oocytes retrieved (1001–2000 IU). The number of patients included in each analysis (N =) is depicted on the appropriate graph

A negative relationship between FSH dose and the number of oocytes retrieved was also identified when subgroup analyses were conducted on the three most common ovarian stimulation protocols (agonist suppression, agonist flare, and antagonist suppression; all P < 0.0001). Compared to the 1001–2000 IU group, the number of oocytes retrieved decreased by 47, 41, and 46% in the agonist suppression, agonist flare, and antagonist suppression categories, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between total FSH dose (IU) and number of oocytes retrieved in patients undergoing fresh autologous IVF cycles, parsed by the three ovarian stimulation protocols (agonist suppression, agonist flare, and antagonist suppression) most common in the data set. FSH dose categories included < 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000, 3001–4000, 4001–5000, and > 5000 IU. FSH dose category was significantly negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved in all ovarian stimulation protocol categories (P < 0.0001). The figure also depicts (red line and text) the decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the highest (> 5000 IU) FSH dose category compared to the category with the highest number of oocytes retrieved (1001–2000 IU). The number of patients included in each analysis (N =) is depicted on the appropriate graph

Likewise when evaluating the relationship between FSH dose and the number of oocytes retrieved in cycles where patients were diagnosed with endometriosis, PCOS, diminished ovarian reserve or tubal disease, unexplained infertility, or other reasons for seeking ART, a negative relationship was identified (P < 0.0001). For all of the above, the highest number of oocytes retrieved was noted in the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose category (Fig. 5). By comparison, the proportional decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the > 5000 IU FSH dose group was 46, 44, 36, and 46% in patients diagnosed with endometriosis, PCOS, diminished ovarian reserve, and tubal disease, respectively. For patients seeking ART due to unexplained infertility or for other reasons, the decrease was 42 and 48%.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between total FSH dose (IU) and number of oocytes retrieved in patients undergoing fresh autologous IVF cycles, parsed by cycles where patients were recorded as having a positive diagnosis for either endometriosis, PCOS, diminished ovarian reserve, tubal disease, unexplained infertility, and those seeking ART for other reasons. FSH dose categories included < 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000, 3001–4000, 4001–5000, and > 5000 IU. FSH dose category was significantly correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved in each of the categories (P < 0.0001). The figure also depicts (red line and text) the decrease in the number of oocytes retrieved in the highest (> 5000 IU) FSH dose category compared to the category with the highest number of oocytes retrieved (1001–2000 IU). The number of patients included in each analysis (N =) is depicted on the appropriate graph

Discussion

The most significant findings of this study show as follows: firstly, that a highly significant inverse relationship, independent of age and patient prognosis, exists between total FSH dose and oocyte retrieval in fresh, autologous ART cycles. The highest number of oocytes retrieved was observed in the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose category and comparatively, the highest dose category (> 5000 IU) was associated with 45 ± 1% decline in the number of oocytes retrieved. This supports increasing evidence that high FSH doses, even in low or poor responders, are detrimental to oocyte retrieval and ART outcomes. Secondly, ~80% of patients received a non-optimal dose, that is, a dose outside of the 1001–2000 IU FSH dose category. Consequently, there is limited evidence for use of high FSH doses during ovarian stimulation.

In previous studies, where more than two gonadotropin (including hMG) doses were investigated, the relationship between dose and oocyte retrieval was curvilinear. Oocyte retrieval increased with dose but the highest doses either did not increase or were detrimental to oocyte retrieval [6, 8, 9, 19, 34–37]. Likewise, when two doses were investigated or doses were termed high or low, the higher dose did not increase the number of oocytes retrieved [1, 12–15, 20, 38, 39]. However, a small number of studies reported contradictory findings [2, 7, 10], contributing to the idea that increasing FSH dose is a suitable strategy for increasing oocyte retrieval rates, particularly, in low or poorly responding patients.

One possible criticism of retrospective correlative analyses such as the one reported herein is that high FSH doses are administered to offset the possibility of cycle cancelation due to a poor response, thereby confounding the analysis. Increased patient age and diagnosis of a diminished ovarian reserve are associated with a poor response to ovarian stimulation and as a result, tend to be associated with higher total FSH doses [18, 40]. However, data presented herein, which were limited to fresh ART cycles, and by others show that using higher FSH doses in patients with either decreased antral follicle counts [14, 20], decreased serum AMH concentrations [16], or increased maternal age [10, 13, 19, 41] did not improve oocyte retrieval rates. We also conducted analyses where ART cycles were categorized by BMI, stimulation protocol, and infertility diagnoses. In all cases, FSH dose was negatively correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved and the highest number of oocytes retrieved was in the 1001–2000 IU dose range. Furthermore, we conducted a subgroup analysis excluding ART cycles where patients were predicted to respond poorly to FSH stimulation, namely, the good prognosis analysis. Despite excluding patients more likely to be prescribed high FSH doses, > 60% of these good prognosis patients still received doses higher than the optimal dose range.

A related criticism could be that patients receiving the lowest doses (< 1000 IU) may be undergoing minimal stimulation IVF cycles, particularly, since data for canceled cycles were not included in the analysis. Whilst the precise reasons for the choice for such a low total FSH dose are not available for this data set, previous studies have shown improved outcomes using minimal stimulation protocols for patients expected to respond poorly, for example, due to increased age or diagnosis of a diminished ovarian reserve [42, 43]. However, < 2% of patients with a diagnosis of a diminished ovarian reserve were included in the < 1000 IU FSH dose group and when patients were categorized by age, the oldest age category (≥ 40 years) had the lowest proportion of patients in the < 1000 IU FSH dose category. Whilst not supporting the use of minimal stimulation IVF protocols either, the analysis indicates that patient characteristics are unlikely to be the sole factors influencing choice of FSH dose during ART. Given that a major objective of ovarian stimulation is to increase the number of high quality oocytes retrieved for IVF whilst minimizing treatment cost and risk of OHSS, the data herein strongly support the use of total FSH doses within the 1001–2000 IU dose range regardless of the predicted responsiveness to ovarian stimulation.

In combination with the previously published analysis of our data set [5], we have demonstrated that total FSH doses greater than 2000 IU are likely to be excessive and detrimental to number of oocytes retrieved and live birth rate [5]. This is consistent with an increasing number of dose–response trials and retrospective, correlative studies also showing that high FSH doses had either no effect or were detrimental to IVF success [7, 10–12, 14–16] and live birth rate [4, 10, 17, 19, 20, 38]. Studies in mice have also shown that high FSH doses may perturb bidirectional communication between the oocyte and surrounding granulosa and cumulus cells and alter the kinetics of nuclear maturation, both of which are known to be detrimental to oocyte quality [22, 23]. Given the potential detrimental effects of high FSH doses on oocyte quality and the number of oocytes retrieved, there appears to be inadequate justification for the use of high FSH doses during ovarian stimulation.

With the available data, it is not possible to determine the precise reasons for the decrease in number of oocytes retrieved observed in the highest FSH dose category. Two potential reasons include a poor ovarian response (number of follicles that developed) or a reduction in oocyte pickup efficiency, that is, the number of oocytes retrieved in relation to the total number of follicles aspirated. Both support our hypothesis and demonstrate that high FSH doses during ovarian stimulation are likely to impair follicular maturation and subsequently decrease oocyte retrieval. With increasing data demonstrating the complexity of FSH and LH signaling pathways [44], it has become apparent that current understanding of the effects of exogenous gonadotropins during ovarian stimulation is incomplete. For instance, luteinization is a normal physiological process occurring in response to LH, following ovulation. However, premature luteinization has been documented in women following administration of high FSH doses during ovarian stimulation and results in significant perturbations in the follicular microenvironment [45–48]. Bovine studies also demonstrate that in cattle, superovulation with high FSH doses did not increase the number of ovulatory sized follicles produced and in fact decreased ovulation rate relative to lower doses [24]. Thus high FSH doses during ovarian stimulation and the resultant changes in the follicular microenvironment may be detrimental to oocyte and embryo quality, and potentially, oocyte recovery rate [22–24, 45, 49–51]. There is also evidence that delayed frozen embryo transfers mitigated the negative effect of high FSH doses on live birth rate and indicate that these high FSH doses may also have detrimental effects on the endometrium [52]. Although, the molecular mechanisms by which high FSH doses alter follicular development and endometrial receptivity are unclear; they warrant further investigation.

A possible limitation of this study is the absence of data regarding the maturity and quality of the oocytes that were retrieved at the different FSH doses. However, the strong inverse relationship between FSH dose and the number of oocytes retrieved (shown in the present study) and FSH dose with live birth rate (shown in the previous study) using the same data set [5] imply that relatively high FSH doses may also be detrimental to oocyte quality.

In conclusion, irrespective of age or other confounding factors, 1001–2000 IU FSH yielded the highest number of oocytes and non-optimal doses, which were administered in the majority of ART cycles, were detrimental to number of oocytes retrieved.

Acknowledgements

SART wishes to thank all of its members for providing clinical information to the SART CORS database for use by patients and researchers. Without the efforts of our members, this research would not have been possible.

Author contribution

Z Clark performed the analyses and initial interpretation of the data, prepared the majority of the first draft of the manuscript, and contributed to all subsequent revisions. M Thakur contributed to interpretation of data, all revisions of the manuscript, and liaised with SART to secure approval for the use of the data set. R Leach provided advice and assisted in the interpretation of data, securing approval from SART for the use of the data set, and contributed to revising the manuscript. J Ireland oversaw this project, including the analysis of the data and the planning and preparation of all drafts of this manuscript.

Data Availability

Not applicable

Code availability

Not applicable

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was previously approved by the Institutional Review Board at Michigan State University [5].

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pereira N, Friedman C, Hutchinson AP, Lekovich JP, Elias RT, Rosenwaks Z. Increased odds of live birth in fresh in vitro fertilization cycles with shorter ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:104–109.e102. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Land JA, Yarmolinskaya MI, Dumoulin JCM, Evers JLH. High-dose human menopausal gonadotropin stimulation in poor responders does not improve in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:961–965. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)58269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leijdekkers JA, Torrance HL, Schouten NE, van Tilborg TC, Oudshoorn SC, Mol BWJ, et al. Individualized ovarian stimulation in IVF/ICSI treatment: it is time to stop using high FSH doses in predicted low responders. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1954–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Lensen SF, Wilkinson J, Leijdekkers JA, La Marca A, Mol BWJ, Marjoribanks J, Torrance H, Broekmans FJ. Individualised gonadotropin dose selection using markers of ovarian reserve for women undergoing in vitro fertilisation plus intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD012693. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012693.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker VL, Brown MB, Luke B, Smith GW, Ireland JJ. Gonadotropin dose is negatively correlated with live birth rate: analysis of more than 650,000 assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1145–1152.e1145. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olivennes F, Howles CM, Borini A, Germond M, Trew G, Wikland M, Zegers-Hochschild F, Saunders H, Alam V, group Cs Individualizing FSH dose for assisted reproduction using a novel algorithm: the CONSORT study. Reprod BioMed Online. 2009;18:195–204. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arce J-C, Nyboe Andersen A, Fernández-Sánchez M, Visnova H, Bosch E, García-Velasco JA, Barri P, de Sutter P, Klein BM, Fauser BCJM. Ovarian response to recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone: a randomized, antimüllerian hormone–stratified, dose–response trial in women undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1633–1640.e1635. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkkanoglu M, Ozgur K. What is the optimum maximal gonadotropin dosage used in microdose flare-up cycles in poor responders? Fertil Steril. 2010;94:662–665. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedler S, Meltzer S, Saar-Ryss B, Rabinson J, Lazer T, Liberty G. An upper limit of gonadotropin dose in patients undergoing ART should be advocated. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:965–969. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2016.1199018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal L, Jindal S, Witt BR, Santoro N. Less is more: increased gonadotropin use for ovarian stimulation adversely influences clinical pregnancy and live birth after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1694–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stadtmauer L, Ditkoff EC, Session D, Kelly A. High dosages of gonadotropins are associated with poor pregnancy outcomes after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:1058–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56756-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Out HJ, David I, Ron-El R, Friedler S, Shalev E, Geslevich J, Dor J, Shulman A, Ben-Rafael Z, Fisch B, Dirnfeld M. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial using fixed daily doses of 100 or 200 IU of recombinant FSH in ICSI cycles. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1104–1109. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.6.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Out HJ, Braat DDM, Lintsen BME, Gurgan T, Bukulmez O, Gökmen O, Keles G, Caballero P, González JM, Fábregues F, Balasch J, Roulier R. Increasing the daily dose of recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (Puregon®) does not compensate for the age-related decline in retrievable oocytes after ovarian stimulation. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:29–35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinkert ER, Broekmans FJM, Looman CWN, Habbema JDF, te Velde ER. Expected poor responders on the basis of an antral follicle count do not benefit from a higher starting dose of gonadotrophins in IVF treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:611–615. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan SL, Child TJ, Cheung AP, Fluker MR, Yuzpe A, Casper R, Leung P, Cadesky K, Davis VJ. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study comparing a starting dose of 100 IU or 200 IU of recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (Puregon®) in women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for ivf treatment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2005;22:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-1497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lekamge DN, Lane M, Gilchrist RB, Tremellen KP. Increased gonadotrophin stimulation does not improve IVF outcomes in patients with predicted poor ovarian reserve. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25:515–521. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterrenburg MD, Veltman-Verhulst SM, Eijkemans MJC, Hughes EG, Macklon NS, Broekmans FJ, Fauser BCJM. Clinical outcomes in relation to the daily dose of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone for ovarian stimulation in in vitro fertilization in presumed normal responders younger than 39 years: a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:184–196. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broer SL, van Disseldorp J, Broeze KA, Dolleman M, Opmeer BC, Bossuyt P, Eijkemans MJC, Mol B-WJ, Broekmans FJM, Broer SL, van Disseldorp J, Broeze KA, et al. Added value of ovarian reserve testing on patient characteristics in the prediction of ovarian response and ongoing pregnancy: an individual patient data approach. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:26–36. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borges E, Jr, Zanetti BF, Setti AS, Braga DPAF, Figueira RCS, Iaconelli A., Jr FSH dose to stimulate different patient' ages: when less is more. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2017;21:336–342. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20170035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Tilborg TC, Torrance HL, Oudshoorn SC, Eijkemans MJC, Koks CAM, Verhoeve HR, Nap AW, Scheffer GJ, Manger AP, Schoot BC, Sluijmer AV, Verhoeff A, Groen H, Laven JSE, Mol BWJ, Broekmans FJM, on behalf of the OPTIMIST study group. van Tilborg TC, Oudshoorn SC, Eijkemans MJC, Mochtar MH, Koks CAM, van Golde RJT, Verhoeve HR, Nap AW, Scheffer GJ, Manger AP, Hoek A, Schoot BC, Oosterhuis GJE, Kuchenbecker WKH, Fleischer K, de Bruin JP, Sluijmer AV, Friederich J, Verhoeff A, van Hooff MHA, van Santbrink EJP, Brinkhuis EA, Smeenk JMJ, Kwee J, de Koning CH, Groen H, van Wely M, Lambalk CB, Laven JSE, Mol BWJ, Broekmans FJM, Torrance HL. Individualized versus standard FSH dosing in women starting IVF/ICSI: an RCT. Part 1: the predicted poor responder. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2496–2505. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Li J, Zhang F, Liu Y, Xu G, Guo J, Zhang R, Wu Y, Liu J, Chen K, Zhao W, Wu W, Hu Y, Chen G, Zhang D. Factors affecting the live-birth rate in women with diminished ovarian reserve undergoing IVF-ET. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:1017–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4884-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Combelles CMH, Carabatsos MJ, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM, Albertini DF. Hormonal control of somatic cell oocyte interactions during ovarian follicle development. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;69:347–355. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts R, Iatropoulou A, Ciantar D, Stark J, Becker DL, Franks S, Hardy K. Follicle-stimulating hormone affects metaphase I chromosome alignment and increases aneuploidy in mouse oocytes matured in vitro1. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:107–118. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karl KR, Jimenez-Krassel F, Gibbings E, Ireland JLH, Clark ZL, Tempelman RJ, et al. Negative impact of high doses of follicle-stimulating hormone during superovulation on the ovulatory follicle function in small ovarian reserve dairy heifers†. Biol Reprod. 2021;104:695–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Lerner SP, Thayne WV, Baker RD, Henschen T, Meredith S, Inskeep EK, Dailey RA, Lewis PE, Butcher RL. Age, dose of FSH and other factors affecting superovulation in Holstein cows. J Anim Sci. 1986;63:176–183. doi: 10.2527/jas1986.631176x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saumande J, Chupin D. Induction of superovulation in cyclic heifers: the inhibitory effect of large doses of PMSG. Theriogenology. 1986;25:233–247. doi: 10.1016/0093-691X(86)90059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Gaast MH, Eijkemans MJC, van der Net JB, de Boer EJ, Burger CW, van Leeuwen FE, Fauser B, Macklon NS. Optimum number of oocytes for a successful first IVF treatment cycle. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;13:476–480. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sunkara SK, Rittenberg V, Raine-Fenning N, Bhattacharya S, Zamora J, Coomarasamy A. Association between the number of eggs and live birth in IVF treatment: an analysis of 400 135 treatment cycles. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1768–1774. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fatemi HM, Doody K, Griesinger G, Witjes H, Mannaerts B. High ovarian response does not jeopardize ongoing pregnancy rates and increases cumulative pregnancy rates in a GnRH-antagonist protocol. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:442–452. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polyzos NP, Drakopoulos P, Parra J, Pellicer A, Santos-Ribeiro S, Tournaye H, Bosch E, Garcia-Velasco J. Cumulative live birth rates according to the number of oocytes retrieved after the first ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a multicenter multinational analysis including ∼15,000 women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:661–670.e661. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferraretti AP, La Marca A, Fauser BCJM, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L, Definition obotEwgoPOR ESHRE consensus on the definition of ‘poor response' to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria†. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1616–1624. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broekmans FJ. Individualization of FSH doses in assisted reproduction: facts and fiction. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2019;10:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Prevention CfDCa, Medicine ASfR, Technology SfAR. 2012 Assisted reproductive technology national summary report. In: Atlanta: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2014.

- 34.Martin JR, Mahutte NG, Arici A, Sakkas D. Impact of duration and dose of gonadotrophins on IVF outcomes. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;13:645–650. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barash OO, Hinckley MD, Rosenbluth EM, Ivani KA, Weckstein LN. High gonadotropin dosage does not affect euploidy and pregnancy rates in IVF PGS cycles with single embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:2209–2217. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shulman A, Ghetler Y, Fejgin M, Kaneti H, Weinstein S, Beyth Y, Ben-Nun I. Relationship between the threshold of ovarian sensitivity to human menopausal gonadotrophin stimulation and in-vitro fertilization treatment outcome. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:3198–3201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griesinger G, Dietrich B, Stöckl L, Eckert K, Goletz S, Tandler-Schneider A. Fully human glyco-optimized recombinant FSH (follitropin epsilon) – a randomized, comparator-controlled phase II clinical trial. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2020;40:331–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Hofmann GE, Toner JP, Muasher SJ, Jones GS. High-dose follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) ovarian stimulation in low-responder patients for in vitro fertilization. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1989;6:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF01139183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hock DL, Louie H, Shelden RM, Ananth CV, Kemmann E. The need to step up the gonadotropin dosage in the stimulation phase of IVF treatment predicts a poor outcome. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15:427–430. doi: 10.1007/BF02744936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oudendijk JF, Yarde F, Eijkemans MJC, Broekmans FJM, Broer SL. The poor responder in IVF: is the prognosis always poor? A systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:1–11. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yong PYK, Brett S, Baird DT, Thong KJ. A prospective randomized clinical trial comparing 150 IU and 225 IU of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (Gonal-F*) in a fixed-dose regimen for controlled ovarian stimulation in in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:308–315. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Q, Wang Y, Sun L, Zhang S, Chai W, Hong Q, Long H, Wang L, Lyu Q, Kuang Y. Controlled ovulation of the dominant follicle using progestin in minimal stimulation in poor responders. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15:71. doi: 10.1186/s12958-017-0291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kushnir VA, Darmon SK, Barad DH, Gleicher N. Observational retrospective study of US national utilisation patterns and live birth rates for various ovarian stimulation protocols for in vitro fertilisation. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e023124. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson GP, Jonas KC. Mechanistic insight into how gonadotropin hormone receptor complexes direct signaling. Biol Reprod. 2020;102:773–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Bosch E, Valencia I, Escudero E, Crespo J, Simón C, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Premature luteinization during gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist cycles and its relationship with in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1444–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ubaldi F, Camus M, Smitz J, Bennink HC, Van Steirteghem A, Devroey P. Premature luteinization in in vitro fertilization cycles using gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) and recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and GnRH-a and urinary FSH. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:275–280. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)58453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tapanainen JS, Lapolt PS, Perlas E, Hsueh AJ. Induction of ovarian follicle luteinization by recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2875–2880. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoolcraft W, Sinton E, Schlenker T, Huynh D, Hamilton F, Meldrum DR. Lower pregnancy rate with premature luteinization during pituitary suppression with leuprolide acetate. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:563–566. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lejeune B, Degueldre M, Camus M, Vekemans M, Opsomer L, Leroy F. In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer as related to endogenous luteinizing hormone rise or human chorionic gonadotropin administration *. Fertil Steril. 1986;45:377–383. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)49220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pangas SA, Li X, Robertson EJ, Matzuk MM. Premature luteinization and cumulus cell defects in ovarian-specific Smad4 knockout mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1406–1422. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hofmann GE, Bentzien F, Bergh PA, John Garrisi G, Williams MC, Guzman I, Navot D. Premature luteinization in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation has no adverse effect on oocyte and embryo quality. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:675–679. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munch EM, Sparks AE, Zimmerman MB, Van Voorhis BJ, Duran EH. High FSH dosing is associated with reduced live birth rate in fresh but not subsequent frozen embryo transfers. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1402–1409. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Not applicable