Abstract

The last common ancestor of all living arthropods had biramous postantennal appendages, with an endopodite and exopodite branching off the limb base. Morphological evidence for homology of these rami between crustaceans and chelicerates has, however, been challenged by data from clonal composition and from knockout of leg patterning genes. Cambrian arthropod fossils have been cited as providing support for competing hypotheses about biramy but have shed little light on additional lateral outgrowths, known as exites. Here we draw on microtomographic imaging of the Cambrian great-appendage arthropod Leanchoilia to reveal a previously undetected exite at the base of most appendages, composed of overlapping lamellae. A morphologically similar, and we infer homologous, exite is documented in the same position in members of the trilobite-allied Artiopoda. This early Cambrian exite morphology supplements an emerging picture from gene expression that exites may have a deeper origin in arthropod phylogeny than has been appreciated.

Subject terms: Evolution, Evolutionary developmental biology, Palaeontology

The common ancestor of all living arthropods had biramous postantennal appendages, with an endopodite and exopodite branching off the limb base. This study uses microtomographic imaging of the Cambrian arthropod Leanchoilia to reveal a previously undetected exite at the base of most appendages, suggesting a deeper origin for exites in arthropod phylogeny.

Introduction

Living arthropods are traditionally thought to have the appendages of their most recent common ancestor consisting of an antenna followed by a set of biramous post-antennal limbs1. Biramy refers to an inner branch (the endopodite) and outer branch (the exopodite), both of which arise from the same section of the limb base, known as the protopodite or basipodite. Correspondences between biramous appendages of crustaceans and Palaeozoic arthropods such as trilobites underpin the presumed homology of the endopodite, exopodite and protopodite and their origin at or deeper than the root of the arthropod crown group1,2. In this framework, some more proximal elements of the limb base, such as the coxa of crustaceans, are thought to have differentiated de novo3 or resulted from subdivision of an originally single part protopodite4.

The canonical view of homology between the two rami of biramous limbs across the arthropods was called into question when clonal analysis of peracarid pancrustaceans revealed that the endopodite and exopodite of their biramous limbs both form from growth zones along the main limb axis, and uniramous limbs result from a failure of this axis to split rather than from loss of the exopodite as traditionally thought5,6. This single axis contrasts with additional outgrowths from the limb base (known as exites), which grow along novel axes. This suggested that the biramous limb in crustaceans differs from the condition seen in many Cambrian arthropods, which was reinterpreted as a uniramous limb and an exite rather than an endopodite and exopodite, respectively5.

Fitting extant chelicerates into this framework is challenged by prosomal appendages generally being uniramous (composed of a telopodite widely homologised with an endopodite) and the opisthosomal appendages being modified into respiratory structures. Even when there is agreement on a theory of ancestral biramy in Chelicerata, the identification of particular structures as either exopodites or exites in chelicerates has been contentious. For example, the flabellum, a projection on leg VI of horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura), has been homologised with either an exopodite1,2 or an exite/epipodite7,8, and the same is true for the book gills2,9. Gene expression data even allow that the book gill opercula include a contribution from the walking leg10. Fossils assigned to the chelicerate stem11 (or crown12) group, such as Offacolus13 and Dibasterium14, have contributed to this debate because they have segmented rami that have been homologised with the endopodite and exopodite of biramous limbs4 and are inferred to have originated by splitting of a single axis7. A distinct identity for the supposed exopodite can nevertheless also be considered, as it appears to emerge from the body wall with distinct separation from the protopodite.

A different approach to evaluating homology of rami and exites is offered by functional studies of leg patterning genes. Comparison of leg gene function in the amphipod Parhyale and Drosophila and other insects serves to homologise the distal six podomeres of crustacean and insect appendages in a one-to-one manner. Combined with expression patterns of wing genes, morphologically varied exites can be associated with more proximal podomeres of the leg, even when they have been incorporated into the body wall15. This approach has been extended to chelicerates by drawing on the spider Acanthoscurria, concluding that chelicerate exites and the inferred exopodite of Silurian chelicerates such as Dibasterium and Offacolus are non-homologous with exopodites of pancrustaceans because they branch from different podomeres7.

In this work, we present evidence for a morphologically distinctive exite in Cambrian arthropods exposed by computed microtomography of fossils from the Cambrian (Series 2, Stage 3) Chengjiang Biota of Yunnan, China. Similarities between this exite in four species support its homology. Comparisons with other fossil and extant arthropods, in light of current phylogenetic frameworks, suggest an early origin of exites in arthropod evolution.

Results and discussion

A previously undetected exite in Cambrian arthropods

The structure of interest is best known from the megacheiran great-appendage arthropod Leanchoilia illecebrosa, in which it has been imaged on both sides of the body in the head and trunk. The exite of this species is illustrated and described in detail, with comparative accounts in another species of Leanchoilia, L. obesa, and in two members of the Artiopoda, Naraoia spinosa and Retifacies abnormalis. Artiopoda is a monophyletic group16 that unites trilobites with Palaeozoic taxa sharing a set of mostly homonomous post-antennal appendages of similar structure.

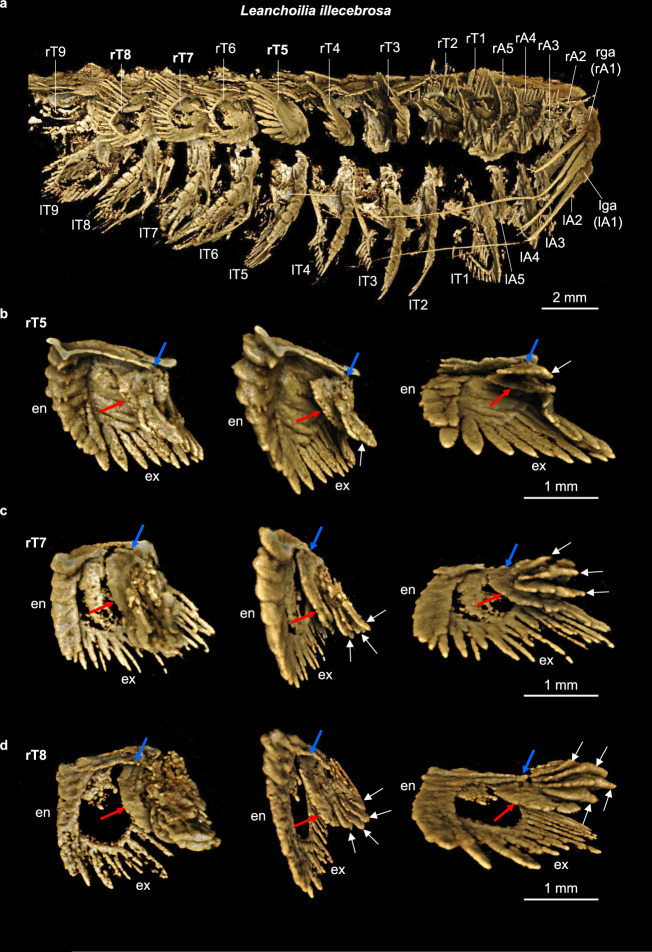

YKLP 11424 is a specimen of Leanchoilia illecebrosa of length 21 mm, preserved in lateral aspect (Supplementary Fig. 1a), complete apart from lacking the posterior portion of the telson. The great appendages, four additional cephalic appendage pairs, and nine preserved pairs of trunk appendages have been digitally dissected on both sides of the body (Supplementary Fig. 2). Most details of the protopodite, endopodite and exopodite of the biramous appendages correspond to previous descriptions of this species17 and the allied L. superlata from the Burgess Shale18,19 and a complete description is not presented.

An outgrowth composed of two to five overlapping lamellae is observed at the proximal edge of the protopodite of the last two head appendages (Supplementary Fig. 3c,d) and in all trunk appendages (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 4) of YKLP 11424. It is hereafter referred to as an exite based on its attachment to the protopodite proximal to that of the exopodite. The number of overlapping lamellae increases on more posterior appendages, there being two on the appendage of trunk segment 5, four on segment 7, and five on segment 8 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 4). Each lamella has a similar flap-like shape, and on each appendage a basal lamella attaches to the protopodite whereas the remaining, overlying lamellae each attach near the base of the basal lamella (Supplementary Movie 1). The specimen bears a morphologically similar exite in the same position on the fourth and fifth cephalic appendages and the first four pairs of trunk appendages, but its preservation is poorer than on the more posterior trunk segments. The more anterior appendages expose only fragments of lamellae (Supplementary Figs. 3c, d, 4a–d, Supplementary Movies 2, 3).

Fig. 1. Computed tomographic images of YKLP 11424 showing selected exite-bearing appendages of Leanchoilia illecebrosa.

a Ventral side of the animal. b–d Digitally dissected trunk appendages 5, 7, and 8 from the right side of the animal (rT5, rT7, rT8). Each appendage is shown at three different angles to demonstrate the endopodite (en), the exopodite (ex) and the exite consisting of one basal flap (red arrow) and several additional ones (white arrows). Blue arrows point to the attachment of the exite. Individual scale bars provided. An, head appendage n; l, left; r, right; ga, great appendage; Tn, trunk appendage n. Dissections of all appendages are available in Supplementary Figs. 2–4.

YKLP 11093 is a specimen of Leanchoilia illecebrosa of length 30 mm and is likewise preserved in lateral aspect (Supplementary Figs. 1b, 5), including the head and entire trunk. The four biramous cephalic appendages and first pair of trunk appendages are well preserved and have been digitally dissected from one side of the body. A lamellar exite is observed on the fourth (Supplementary Fig. 5d) and fifth (Supplementary Fig. 5e) cephalic appendages and on the first trunk appendage (Supplementary Fig. 5f, Supplementary Movie 4), in each case being composed of flap-like lamellae. The lamellae are best preserved on the first trunk appendage, in which they consist of the basal lamella and two overlapping lamellae. The margins of the exite lamellae are fringed by a few setae (Supplementary Fig. 5d), which are well shown by additional specimens (YKLP 10938, 11089; see below). A series of appendages shows the exopodite folded along the hinge by which it attaches to the protopodite, such that the exite comes to lie between the endopodite and exopodite (Supplementary Fig. 6). The endopodite, exopodite and exite are each oriented in a different plane, rejecting the possibility that the exite attaches to the exopodite rather than having an independent attachment to the protopodite.

Information from the two specimens thus indicates a consistent appearance of the lamellae on the last two cephalic appendages but suggests minor variation in the number of lamellae on anterior trunk appendages (i.e., two versus three), potentially related to differences in body size.

YKLP 10938 and 11089 are two complete specimens of L. illecebrosa in lateral aspect. The exites are visible on posterior cephalic and anterior trunk appendages in light microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 7), revealing up to nine setae of variable length fringing the margin of a lamella (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

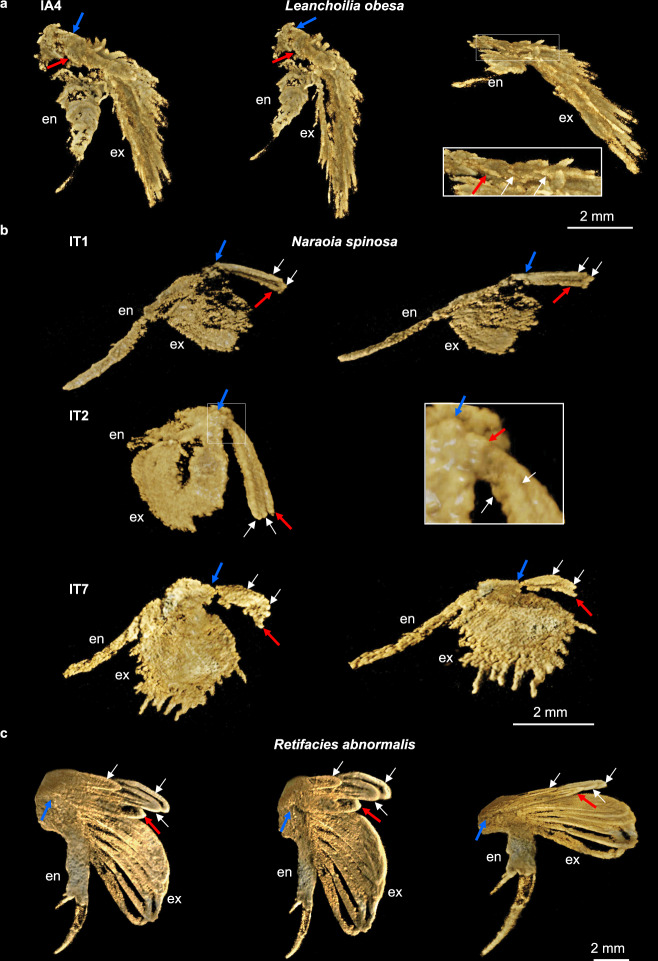

YKLP 13323 is a complete specimen of Leanchoilia obesa, the holotype of the species, preserved in dorsal view (Supplementary Fig. 1c). An appendage from the head (lA4 in Supplementary Fig. 8a) has been digitally dissected (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Movie 5) to reveal very similar morphology to exites on cephalic and trunk appendages of L. illecebrosa. An exite attaches at the same position on the protopodite, composed of a basal lamella and two additional flap-like lamellae overlapping it (Fig. 2a inset). Each of these overlying lamellae attaches proximally, but their exact attachment is less clear in this species.

Fig. 2. Computed tomographic images showing exite-bearing appendages.

a Leanchoilia obesa (YKLP 13323). b Naraoia spinosa (YKLP 11425). c Retifacies abnormalis (YKLP 11426). Each appendage is shown at different angles to demonstrate the endopodite (en), the exopodite (ex) and the exite consisting of one basal flap (red arrow) and several additional ones (white arrows). Blue arrows point to the attachment of the exite. Individual scale bars provided. An, head appendage n; l, left; r, right; Tn, trunk appendage n. CT images of the entire specimens are available in Supplementary Fig. 8.

YKLP 11425 is a complete specimen of Naraoia spinosa with the head shield folded at a high angle relative to the trunk shield, as is common in this species (Supplementary Figs. 1d, 8b). Three trunk appendages, lT1, lT2 and lT7 (Supplementary Fig. 8b), have been digitally dissected (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Movie 6) and reveal exites similar to those of Leanchoilia. An outgrowth consisting of three overlapping lamellae affixes to the proximal-most portion of the protopodite, narrowly overlapping the exopodite. One of these exites has relatively short and wide lamellae, whereas the better-preserved ones have longer, narrower lamellae that all terminate at almost the same length. The exite lamellae become shorter and broader posteriorly. The basal lamella attaches to the protopodite whereas the overlying lamellae each attach near the base of the basal lamella (Fig. 2b).

YKLP 11426 is a fragmentary specimen of Retifacies abnormalis, preserving only the trunk (Supplementary Figs. 1e, 8c, 9a,b), but is confidently identified by diagnostic reticulate sculpture on the tergum, pygidial shape, and a styliform, annulated telson. Several trunk appendages bear proximal outgrowths from the protopodite (Supplementary Fig. 8c). One of the appendages has been digitally dissected (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Movie 7) to reveal a similar situation seen in Leanchoilia and Naraoia. Four lamellae of various sizes originate from the proximal portion of the protopodite. The lamellae are elongate and paddle-shaped, of similar morphology to both each other and to the exopodite lamellae. The lamellae are imbricated with the basal lamella offset distally, and the overlying lamellae being grouped more proximally. Each lamella attaches to the protopodite independently.

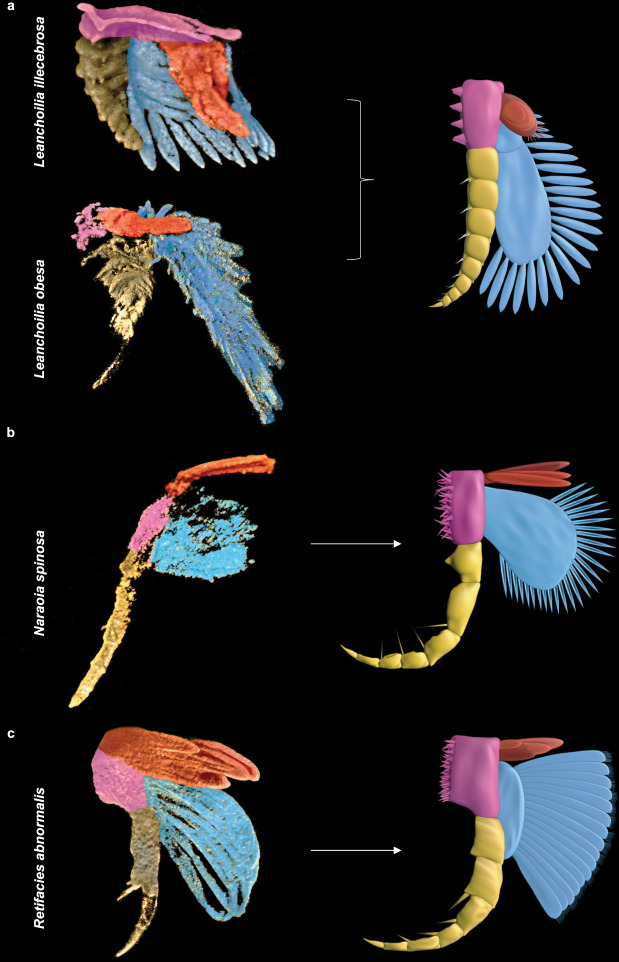

The exites of Leanchoilia, Naraoia and Retifacies resemble each other in being composed of a few (two to five) overlapping lamellae and emerging from the proximal portion of the protopodite (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 10). An additional shared character of Leanchoilia and Naraoia is that the basal lamella forms the attachment to the protopodite and the overlapping lamellae branch from the basal lamella (Fig. 3). The lamellae of the exite of Retifacies resemble those of the exopodite in both having a similar paddle-like shape, but in all three cases the exite is regarded as a discrete structure rather than being an outgrowth of the exopodite, like the divided exopodite called a pseudepipodite in cephalocarids20. Naraoia in particular shows a clear separation of the attachment of the exite and exopodite and a marked difference in the morphology of the two branches.

Fig. 3. Three-dimensional models of exite-bearing appendages.

a Leanchoilia illecebrosa and Leanchoilia obesa. b Naraoia spinosa. c Retifacies abnormalis. Protopodite, endopodite and exopodite are coloured in pink, yellow and blue, respectively. Exite is in red and has not previously been detected. Not to scale. Digitally dissected protopodite, endopodite, exopodite, and exite are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Exites have multiple origins

Among the varied kinds of exites known in arthropods, comparisons with Cambrian fossils have mostly focused on the epipodites of crustaceans, which can unequivocally be distinguished from the exopodite of a limb when both are present (as is likewise the case in the Cambrian species studied here). Epipodites are unmusculated flaps or clubs originating proximal to the exopodite on the coxal or precoxal part of the protopodite of post-maxillulary appendages4,21, serving an osmoregulatory or respiratory function22. Based on differences in position and morphology, exites and even more specifically epipodites have been ascribed multiple independent origins within Pancrustacea1, although some correspondences in gene expression are consistent with their homology between such divergent groups as branchiopods and malacostracans4. The pancrustacean Yicaris dianensis from Cambrian Series 2, Stage 323 figures prominently in discussion about the timing of origin of epipodites. A series of leaf-shaped exites in Yicaris has been interpreted as epipodites22,23 or as exites of an independently evolved nature4,21. Irrespective of this debate, leaf-shaped epipodites on the biramous trunk appendages of Ercaicunia multinodosa, a stem-group pancrustacean, attest to their origin by Cambrian Stage 324.

The absence of epipodites in some lineages of Pancrustacea weakens the case for epipodites being so deeply nested in Mandibulata that the exites in Leanchoilia and Artiopoda are their homologues, although Ercaicunia suggests an earlier origin in Pancrustacea than is predicted by extant lineages on their own24. The likely multi-fold derivation of epipodites within Pancrustacea and the discovery of a previously undetected exite with a distinctive lamellar structure in distantly allied Cambrian arthropods are most compatible with epipodites and lamellar exites having independent evolutionary origins. However, it is emerging that exites are more common in arthropods than is commonly assumed. In addition to the flabellum of xiphosuran chelicerates noted above, expression of leg patterning genes and wing genes suggests that the coxal and tergal plates of amphipod crustaceans, paratergal outgrowths and tracheae of insects, and wings of pterygote insects are modified exites7,15. Adding the fossil data presented here, which cover previously unsampled arthropod lineages, exites may have a deeper origin in arthropod phylogeny than has been thought.

Implications for exopodites and exites in chelicerates

Interpreting the phylogenetic significance of similarities between Megacheira and Artiopoda is complicated by both groups repeatedly being placed in two different positions on the arthropod tree. Megacheira is resolved by character argumentation or quantitative phylogenetic analyses as either stem-group Euarthropoda25,26 or as stem-group Chelicerata27–30. Trilobites and other artiopodans are alternatively allied to Mandibulata31–34 or to Chelicerata26,35. The latter is consistent with the historical Arachnomorpha36,37 or Lamellipedia38 hypotheses, the latter named for lamellate setal blades in the exopodite. The evidence for homology of the lamellar exites in Megacheira (Leanchoilia) and Artiopoda (Naraoia, Retifacies) presented here suggests a single origin of this trait and accordingly, assuming that this trait is apomorphic, a close phylogenetic affinity between these taxa. Since both groups have been allied with chelicerates and both are recovered in some phylogenetic analyses in the chelicerate stem-group35, this character may serve as a synapomorphy of a clade within total-group Chelicerata. An alternative interpretation would be that this kind of exite is a symplesiomorphy, potentially retained from flaps bearing setal blades in stem-group arthropods such as Opabinia39. However, Leanchoilia and Naraoia shared detailed similarity in the mode of growth of overlapping lamellae via the attachment of overlying lamellae to the basal lamella, so a symplesiomorphy interpretation would force an exite composed of a few overlapping lamellae to be present throughout the arthropod stem-group/crown-group transition but to have gone undetected.

The likely attachment of the exopodite of the chelicerates Dibasterium and Offacolus to the body wall rather than to the protopodite noted above may be approximated in trilobites. It has recently been argued that the exopodite of the Cambrian trilobite Olenoides serratus attaches partly to the body wall and partly to the limb base40. In conjunction with previous work, which suggests that exopodite and endopodite form by the splitting of the main leg axis5,6 and that exopodites of different arthropod groups originate on different podomeres7, these findings reinforce the argument that the trilobite exopodite may not be homologous with the pancrustacean exopodite.

Our proposal that a lamellar exite is homologous in Artiopoda and Megacheira carries a prediction that a corresponding exite is present in other representatives of these groups, as well as in lineages separating them in the phylogeny. Microtomography of early-derived trilobites and stem-group chelicerates offers potential for discovering additional instances of this structure. Palaeontological data for additional morphologies of exites add to the emerging picture from gene expression in extant arthropods that exites are a more pervasive source of evolutionary novelty in appendage form than has been appreciated.

Methods

Material

Leanchoilia illecebrosa (YKLP 11424, YKLP 11093), Naraoia spinosa (YKLP 11425): Collected from Yu’anshan Member, Chiungchussu Formation, Eoredlichia-Wutingaspis trilobite biozone, Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3, Mafang village, Haikou county, Kunming, Yunnan, China (24°46'20” N, 102°35'10” E). Leanchoilia obesa (YKLP 13323), Retifacies abnormalis (YKLP 11426, YKLP 11430): Collected from Yu’anshan Member, Chiungchussu Formation, Eoredlichia-Wutingaspis trilobite biozone, Cambrian Series 2, Stage 3, Ercaicun village, Haikou county, Kunming, Yunnan, China (24°47’ N, 102°34’ E).

Microscopic observation and documentation

Fossils were observed and prepared under a Leica M205 microscope. Macrophotography shown in Supplementary Figs. 1, 7, and 9 was first undertaken using a digital camera (Olympus E-20P) linked to a microscope Leica MZ12, and, for higher resolution, repeated with a Canon EOS 5DSR camera (DS126611) coupled with a MP-E 65 mm macro photo lens, illuminated with a LEICA LED5000 MCITM. Similar results were obtained, and the higher resolution imagery was used in this work. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CC 2018 and arranged into figures with Microsoft Office 2016.

Micro-computed tomography and 3D rendering

All specimens were scanned with a Micro-X ray-CT: Xradia 520 Versa (Carl Zeiss X-ray Microscopy, Inc., Pleasanton, USA). Except for YKLP 13323 (Leanchoilia obesa; scanned at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences), all other specimens were scanned at the Yunnan Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology, Institute of Palaeontology, Yunnan University, Kunming, China.

Scanning parameters are as follow: Leanchoilia illecebrosa (YKLP 11424): Beam strength: 50 kV/4wW, no Filter, Resolution: 8.92 µm, Number of TIFF images: 2558. Leanchoilia illecebrosa (YKLP 11093): Beam strength: 50 kV/4 W, no Filter, Resolution: 9.90 µm, Number of TIFF images: 3390. Leanchoilia obesa (YKLP 13323): Beam strength: 70 kV/6 W, no Filter, Resolution: 9.99 µm, Number of TIFF images: 2030. Naraoia spinosa (YKLP 11425): (1) For the entire specimen: Beam strength: 60 kV/5 W, no Filter, Resolution: 11.87 µm, Number of TIFF images: 1974; (2) For the appendages: Beam strength: 70 kV/6 W, no Filter, Resolution: 6.22 µm, Number of TIFF images: 2362. Retifacies abnormalis (YKLP 11426): (1) For the entire specimen: Beam strength: 60 kV/5 W, Filter: LE4, Resolution: 27.45 µm, Number of TIFF images: 2534; (2) For the appendages: Beam strength: 60 kV/5 W, no Filter, Resolution: 17.01 µm, Number of TIFF images: 3864. Retifacies abnormalis (YKLP 11430): Beam strength: 70 kV/6 W, Filter: LE4, Resolution: 17.39 µm, Number of TIFF images: 1014. All TIFF images were imported into the software Drishti (Version 2.4) to generate 3D models and enable digital dissections of various structures. Images were captured with the same software, processed with Adobe Photoshop CC 2018, and arranged into figures with Microsoft Office 2016. 3D reconstructions shown in Fig. 3 were produced in Blender 2.90.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NSFC grant 41861134032, DFG grant Me-2683/10-1, and Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province grants 2015HA021, 2018FA025, 2018IA073 and 2019DG050. We thank Joachim T. Haug (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) for discussions and Geoff Boxshall (The Natural History Museum) and Gerhard Scholtz (Humboldt-Universität Berlin) for reading an earlier draft.

Author contributions

Y.L. and G.D.E. designed the research. Y.L., R.R.M., and X.H. secured the funding. X.H. and D.Z. collected all the material except for Naraoia spinosa (YKLP 11425), which was collected by Y.L. M.Z. documented all the specimens with macrophotography. H.M. scanned all the specimens except for YKLP 13323 (Leanchoilia obesa). Y.L. rendered the 3D models of Leanchoilia and M.Z. rendered that of Naraoia and Retifacies. M.S. generated all the 3D reconstructions shown in Fig. 3. G.D.E. and A.D.B. wrote the paper with input from all other authors. All authors participated in the interpretation of the material and the discussions.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The raw CT data generated in this study have been deposited in Zenodo (open access) [10.5281/zenodo.4782778].

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Heather Bruce, Russell Garwood and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gregory D. Edgecombe, Email: g.edgecombe@nhm.ac.uk

Xianguang Hou, Email: xghou@ynu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-24918-8.

References

- 1.Boxshall GA. The evolution of arthropod limbs. Biol. Rev. 2004;79:253–300. doi: 10.1017/S1464793103006274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walossek, D. & Müller, K. J. in Arthropod Relationships (eds Fortey, R. A. & Thomas, R. H.) 139–153 (Chapman & Hall, 1997).

- 3.Waloszek D, Maas A, Chen J, Stein M. Evolution of cephalic feeding structures and the phylogeny of Arthropoda. Palaeogeog., Palaeoclimatol., Palaeoecol. 2007;254:273–287. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boxshall, G. in Arthropod Biology and Evolution (eds Minelli, A. et al.) 241–267 (Springer, 2013).

- 5.Wolff C, Scholtz G. The clonal composition of biramous and uniramous arthropod limbs. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2008;275:1023–1028. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hejnol A, Scholtz G. Clonal analysis of Distal-less and engrailed expression patterns during early morphogenesis of uniramous and biramous crustacean limbs. Dev. Genes Evol. 2004;214:473–485. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce, H. S. How to align arthropod leg segments. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2021.01.20.427514 (2021).

- 8.Mittmann B, Scholtz G. Distal-less expression in embryos of Limulus polyphemus (Chelicerata, Xiphosurida) and Lepisma saccharina (Insecta, Zygentoma) suggests a role in the development of mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and the CNS. Dev. Genes Evol. 2001;211:232–243. doi: 10.1007/s004270100150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki Y, Bergström J. Respiration in trilobites: a reevaluation. GFF. 2008;130:211–229. doi: 10.1080/11035890809452774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma PP. Chelicerates and the conquest of land: a view of arachnid origins through an evo-devo spyglass. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2017;57:510–522. doi: 10.1093/icb/icx078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamsdell JC. Horseshoe crab phylogeny and independent colonizations of fresh water: ecological invasion as a driver for morphological innovation. Palaeontology. 2016;59:181–194. doi: 10.1111/pala.12220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang B, et al. Cretaceous arachnid Chimaerarachne yingi gen. et sp. nov. illuminates spider origins. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:614–622. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton MD, Briggs DEG, Siveter DJ, Siveter DJ, Orr PJ. The arthropod Offacolus kingi (Chelicerata) from the Silurian of Herefordshire, England: computer based morphological reconstructions and phylogenetic affinities. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:1195–1203. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briggs DEG, et al. Silurian horseshoe crab illuminates the evolution of arthropod limbs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci., USA. 2012;109:15702–15705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205875109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce HS, Patel NH. Knockout of crustacean leg patterning genes suggests that insect wings and body walls evolved from ancient leg segments. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:1703–1712. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-01349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortega-Hernández J, Legg DJ, Braddy SJ. The phylogeny of aglaspidid arthropods and the internal relationships within Artiopoda. Cladistics. 2013;29:15–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Hou X, Bergström J. Chengjiang arthropod Leanchoilia illecebrosa (Hou, 1987) reconsidered. GFF. 2007;129:263–272. doi: 10.1080/11035890701293263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Bellido DC, Collins D. Reassessment of the genus Leanchoilia (Arthropoda, Arachnomorpha) from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, British Columbia, Canada. Palaeontology. 2007;50:693–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00649.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haug J, Briggs DEG, Haug C. Morphology and function in the Cambrian Burgess Shale arthropod Leanchoilia superlata and the application of a descriptive matrix. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012;12:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boxshall GA. Crustacean classification: on-going controversies and unresolved problems. Zootaxa. 2007;1668:313–325. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.1668.1.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boxshall G, Jaume D. Exopodites, epipodites and gills in crustaceans. Arthropod Syst. Phylog. 2009;67:229–254. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maas A, et al. Early crustacean evolution and the appearance of epipodites and gills. Arthropod Syst. Phylog. 2009;67:255–273. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Siveter DJ, Waloszek D, Maas A. An epipodite-bearing crown-group crustacean from the Lower Cambrian. Nature. 2007;449:595–598. doi: 10.1038/nature06138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhai D, et al. Three-dimensionally preserved appendages in an early Cambrian stem-group pancrustacean. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budd GE. A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem. Nature. 2002;417:271–275. doi: 10.1038/417271a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Legg DA, Sutton MD, Edgecombe GD. Arthropod fossil data increase congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2485. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J-Y, Waloszek D, Maas A. A new ‘great-appendage’ arthropod from the Lower Cambrian of China and homology of chelicerate chelicerae and raptorial antero-ventral appendages. Lethaia. 2004;37:3–20. doi: 10.1080/00241160410004764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotton TJ, Braddy SJ. The phylogeny of arachnomorph arthropods and the origin of the Chelicerata. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb.: Earth Sci. 2004;94:169–193. doi: 10.1017/S0263593300000596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Ortega-Hernández J, Zhai D, Hou X. A reduced labrum in a Cambrian great-appendage euarthropod. Curr. Biol., 2020;30:2057–2061.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng H, Zhao F, Niu K, Zhu M, Huang D. An early Cambrian euarthropod with radiodont-like raptorial appendages. Nature. 2020;588:101–105. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boudreaux, H. B. Arthropod Phylogeny—with Special Reference to Insects (Wiley, 1979).

- 32.Scholtz, G. & Edgecombe, G. D. in Crustacea and Arthropod Relationships (eds Koenemann, S. & Jenner, R.) 139–165 (CRC Press, 2005).

- 33.Zeng H, Zhao F, Yin Z, Zhu M. Appendages of an early Cambrian metadoxidid trilobite from Yunnan, SW China support mandibulate affinities of trilobites and artiopods. Geol. Mag. 2017;154:1306–1328. doi: 10.1017/S0016756817000279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholtz G, Staude A, Dunlop J. Trilobite compound eyes with crystalline cones and rhabdoms show mandibulate affinities. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2503. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aria C. Macroevolutionary patterns of body plan canalization in euarthropods. Paleobiol. 2020;46:569–593. doi: 10.1017/pab.2020.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Størmer L. On the relationships and phylogeny of recent and fossil Arachnomorpha. A comparative study on Arachnida, Xiphosurida, Eurypterida, Trilobita, and other fossil Arthropoda. Skr. Utg. Nor. Vidensk. -Akad. Oslo, I. Mat. -Naturvidensk. Kl. 1944;5:1–158. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergström J. The oldest arthropods and the origin of Crustacea. Acta Zool. 1992;73:287–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-6395.1992.tb01093.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou X, Bergström J. Arthropods of the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna, southwest China. Foss. Strat. 1997;45:1–116. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Budd GE, Daley AC. The lobes and lobopods of Opabinia regalis from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Lethaia. 2012;45:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00264.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou J, Hughes NC, Hopkins MJ. The trilobite upper limb branch is a well-developed gill. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabe7377. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe7377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The raw CT data generated in this study have been deposited in Zenodo (open access) [10.5281/zenodo.4782778].