Abstract

This investigation aimed to determine the relatedness of dominant occurring soil Streptomyces spp. in Northern Jordan based on their RAPD-PCR fingerprints, and to compare RAPD technique with the conventional phenotypic characterization of Streptomyces isolates. Fifty-eight white and gray color-bearing aerial mycelia antibiotic active-producing Streptomyces soil isolates along with three reference strains were genetically analyzed by RAPD-PCR. Polymorphisms between the isolates showed 1 to 10 bands per isolate and ranged from 200 to 3200 bp in size. Results revealed one common band of ~600 bp shared by ~85% of the isolates, and the observation of bands specific to some reference strains and some soil isolates. When RAPD patterns were analyzed with the UPGMA, results revealed clustering the tested isolates into two equal main super clusters (50% each). Super cluster I appeared to be homogenous and include the three reference strains. However, super cluster II was heterogeneous and but not including any of the reference strains. The association of the antibiotic activity of the dominant white and gray aerial mycelium-bearing Streptomyces isolates to RAPD clustering is reported for the first time, and the RAPD-PCR fingerprints generated here deserve to be cloned, characterized and sequenced in future as Streptomyces species-specific DNA markers. The more random primers used in the analysis may add to RAPD technique a cost-effective, fast, precise result, and less labor work solution for analyzing the similarities and differences among the Streptomyces isolates.

Keywords: Antibiotic, Cluster, Dominant, RAPD-PCR, Streptomyces

Abbreviations: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; SCNA, Starch Casein Nitrate Agar; Taq, Thermus aquaticus; TSB, Tryptic Soy Broth; RAPD, Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA; RFLP, Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism; UPGMA, Unweighted Pair Group Mathematical Analysis

1. Introduction

Streptomycetes are widely distributed in soil and identification of members of the genus Streptomyces represents a great benefit, as they are rich source of most important pharmaceutical products (Chen et al., 2018, Janardhan et al., 2014, Li et al., 2019, Yoon et al., 2017, Yuan and Carwford, 1995) as well as for their activities as biological control and plant growth promoters (El-Tarabily et al., 2019, El-Tarabily et al., 2020, Kamil et al., 2018, Mathew et al., 2020, Saeed et al., 2017). Many classification schemes were proposed to record the vast number of Streptomyces species; majority of them based on a few subjectively chosen cultural properties as well as biochemical, nutritional and physiological characters (Küster and Williams, 1964, Shirling and Gottlieb, 1966). This analysis in addition to the failing or deficiency of taxonomists to find reliable and accurate test for the identification of Streptomyces as source of biotechnological products, has lead to many identification methods developed by researchers for these valuable industrial and pharmaceutical organisms (Williams et al., 1983b, Ochi, 1995, Beyazova and Lechvalier, 1993, Lebada, 1993, Mehling et al., 1995, Martin et al., 2000, Kong et al., 2001, Williams et al., 1983a).

The importance of Streptomyces in bio-industry emphasizes the application of more simple, accurate, and fast new identifying methods. Williams et al. (1983b) pointed out that there are no simple and rapid procedures for objective identification of Streptomyces. Until now, conventional procedures for correct identification are still the only choice. Garaibeh et al. (2003) in their report emphasized that modern Streptomyces identification systems are still developing and mainly by using phage susceptibility, analysis of ribosomal protein sequence (Ochi, 1995), RFLP (restriction fragment length polymorphism) analysis (Beyazova and Lechvalier, 1993) and DNA-DNA hybridization (Lebada, 1993). However, all the methods that were used for the identification of Streptomyces suffered from time consumption, high expenses, efforts or uncertain results.

The use of arbitrary primers to locate RAPD markers in streptomycetes was first done by Mehling et al., (1995). This identification system helped Yuan and Carwford (1995) to apply RAPD methodology in generating specific probe for Streptomyces lydicus WYEC 108 that proved to be effective in detecting and identifying S. lydicus using DNA extracted from pure cultures of Streptomyces. Others RAPD studies also proved to be effective in identifying S. lydicus (Roberts and Crawford, 2000) even when inoculated in soil. Later Martin et al. (2000) detected interspecific, intraspecific and intraclonal polymorphisms among species and strains of Streptomyces rapidly, sensitively and specifically by the use of RAPD methodology. In a more advanced step to apply RAPD technique in the identification of species of Streptomyces, DNA primers were designed for specific detection and identification of S. saraceticus N45 by amplifying specific RAPD fragments in a nested manner (Kong et al., 2001). The generated RAPD fragments profile proved to be used as markers for the identification of S. saraceticus N45 as these fragments specifically occur in a single copy number in its genome (Kong et al., 2001).

RAPD was also applied for the rapid typing of the antibiotic producing Streptomyces and to discriminate between Streptomyces isolates recovered from soils in Jordan and how this methodology could detect genetic diversity among Streptomyces (Garaibeh et al., 2003). In their study, they found that it is possible to use RAPD technique in identification of Streptomyces at the species level.

Several studies have been conducted about the occurrence of Streptomyces flora in different soil habitats in Jordan and their activity to produce inhibitory compounds. (Abussaud and Saadoun, 1991, Saadoun and Al-Momani, 1997a, Saadoun and AL-Momani, 1997b, Saadoun et al., 1998, Saadoun et al., 1999, Saadoun and Gharaibeh, 2002, Saadoun and Gharaibeh, 2003, Saadoun et al., 2000, Saadoun et al., 2007, Saadoun et al., 2008, Saadoun et al., 2017). These studies had demonstrated that white and gray bearing aerial mycelium Streptomyces spp. were the most dominant aerial mycelia colors over the other ones. However, they did not include the clustering and association of the dominant occurring antibiotic-producing white and gray aerial mycelia bearing streptomycetes with RAPD analysis. Therefore, the work presented here aimed specifically to isolate the antibiotic-producing white and gray aerial mycelia Streptomyces from soils in Jordan and to analyze the similarities and differences of these isolates according to their RAPD-PCR fingerprints, and to compare RAPD clustering with the conventional phenotypic grouping and characterization of Streptomyces isolates.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling, isolation, characterization and detection of antibacterial activity

Collection of soil samples and isolation of streptomycetes were done according to procedure described before by Saadoun and Al-Momani (Saadoun and Al-Momani, 1997a). Characterization was carried out according to Williams et al., 1983a, Williams et al., 1983b). Ability of Streptomyces isolates to produce inhibitory substances was assayed by the plate diffusion method (Bauer et al., 1966) towards Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

2.2. Bacterial cultures

Table 1 shows the different Streptomyces cultures that were used in this study. Streptomyces lividans ATCC 35287, S. halstedii ATCC 10897 and S. violaceoruber ATCC 3355 were used as positive controls. The white and gray antibiotic-producing Streptomyces strains (Table 1) were isolated from soils in Northern Jordan and proved to be active against several antibiotic-resistant pathogens (Odat, 2004). All tested bacteria that showed antibiotic resistant to several antibiotics were kindly provided by the clinical labs of some local hospitals in Northern Jordan.

Table 1.

Streptomyces isolates or reference strains investigated in this study.

| No. | Isolate/Ref. strain | Reference | No. | Isolate/Ref. strain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | S124D | This Study | 100 | H14 | This Study |

| 6 | B9 | This Study | 101 | C11 | This Study |

| 9 | B10 | This Study | 108 | C18 | This Study |

| 12 | 21 g | This Study | 109 | C16 | This Study |

| 14 | S163 | This Study | 110 | C110 | This Study |

| 20 | A37 | This Study | 116 | J18 | This Study |

| 22 | A38 | This Study | 118 | J21 | This Study |

| 24 | A39 | This Study | 120 | B12 | This Study |

| 26 | Aj46 | This Study | 122 | S. halstediia | ATCC 10897 |

| 28 | HX10 | This Study | 123 | S. lividans | ATCC 35287 |

| 31 | S13 | This Study | 124 | S. violaceoruber | ATCC 3355 |

| 32 | S144 | This Study | 125 | H18 | This Study |

| 34 | N2b2 | This Study | 126 | H11 | This Study |

| 36 | PR11 | This Study | 129 | Es24 | This Study |

| 38 | N4b4 | This Study | 131 | H17 | This Study |

| 45 | A34 | This Study | 132 | J17 | This Study |

| 46 | A30 | This Study | 133 | HA6 | This Study |

| 50 | S16 | This Study | 134 | Er2 | This Study |

| 52 | A11 | This Study | 136 | B5 | This Study |

| 54 | S138 | This Study | 138 | Es21 | This Study |

| 61 | H19 | This Study | 139 | J113 | This Study |

| 65 | C17 | This Study | 141 | J14 | This Study |

| 69 | C111 | This Study | 143 | HS4 | This Study |

| 70 | H13 | This Study | 145 | HS3 | This Study |

| 72 | C21 | This Study | 146 | Es29 | This Study |

| 74 | H116 | This Study | 147 | H1x | This Study |

| 84 | C1x | This Study | 148 | Ha2 | This Study |

| 85 | C15 | This Study | 149 | H1y | This Study |

| 86 | C14 | This Study | 150 | Ha5 | This Study |

| 89 | C113 | This Study | 151 | R2 | This Study |

| 95 | C22 | This Study |

S.: Streptomyces; Codes refer to Streptomyces isolates.

2.3. Growth conditions

Streptomyces isolates that exhibited significant or unfamiliar antibiosis profile towards E. coli and S. aureus (Table 2) were cultured on tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Oxoid) (Hopowood et al., 1985) (per liter) 30 g, at 28 °C with shaking at 140 rev/min for 48 h. Purity of the Streptomyces cultures were tested by plating 0.1 ml from the broth on starch casein nitrate agar (SCNA) (Küster and Williams, 1964) plates and incubated at 28 °C for 72 h.

Table 2.

Activity of the different Streptomyces isolates against different antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

| Color Series | No. of Isolates | No. of Active Isolates | Anti-bacterial Activity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | |||

| White | 89 (50.3%) | 36 (40.45%) | 29 (80.55%) | 17 (47.22%) |

| Gray | 88 (49.7%)a | 22 (25%) | 18 (81.81%) | 5 (22.72%) |

| Total | 177 (100%) | 58 (32.77%) | 47 (81%) | 22 (37.93%) |

bIsolate is considered active when the inhibition zone is 18 mm or more.

Numbers in parenthesis represent the percent out of the total

2.4. Extraction of genomic DNA from pure Streptomyces isolates

Extraction of genomic DNA was performed using Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA) following manufacturer instructions.

2.5. Estimation of the purity and quantity of the extracted DNA

Purity and quantity of the isolated DNA was tested by spectrophotometric method (Saadoun et al., 2008).

2.6. RAPD analysis

Five random primers (Operon Technologies, USA), 10 mer long each, were separately used in the RAPD study. Three of the primers (OPA02, OPA09, and OPA10) were tested before in the literature (Garaibeh et al., 2003, Malkawi et al., 1999) and proved its success in determining the discrimination and reproducibility of each primer. Three trials of amplifications for each primer (OPA02: 5‘-TGCCGAGCTG-3‘; OPA08: 5‘-GTGACGTAGG-3‘; OPA09: 5‘-GGGTAACGCC-3‘; OPA10: 5‘-GTGATCGCAG-3‘ and OPA18: 5‘-AGGTGACCGT-3‘) were conducted separately and the profile of each experiment was compared to the previous one (Arbeit 1994). Amplification reactions were performed according to Williams et al. (1990) in total volumes of 25 μl containing 2 μl of 0.5 μmol/1primer, 2.5 μl of 10X PCR Buffer (MgCl2 free) (Finzyme, Finland), 1 μl of 50 mM MgCl2 (Promega, USA), 0.25 μl of 10 mM dNTPs mixture (Promega, USA), 0.5 μl of 2U/μl Taq DNA Polymerase (Finzyme, Finland), and 2.5 μl template DNA. Nucleases free water (Promega, USA) was added to a final volume of 25 μl.

PCR amplification was carried out in 0.2 ml, nucleases free PCR tubes (Treff Lab, Switzerland) using iCycler thermocycler (Bio-Rad, USA) with the following program: initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min for 1 min for 45 cycles, followed by annealing at 33 °C for 30 s and extinction at 72 °C for 1 min. Finally, extension at 72 °C for 7 min in which the reactions were held at 4 °C for direct processing or stored at −20 °C until needed.

2.7. Electrophoresis and photography

PCR products were checked for DNA profile by standard electrophoresis procedures (Saadoun et al. 2007) with 1.5% w/v agarose gel (Promega, USA) in 0.5 × TBE buffer. Fotodyne U.V. illuminator (Fotodyne Inc., USA) was used to view and photographed the gels using Polaroid MP4+ Instant Camera System (Polaroid corp., USA).

2.8. Data analysis of RAPD profiles

An engineer’s disk with a magnifying lens was used to analyze the RAPD photographs. The binary matrix was generated based on the fingerprints for each primer which were reported as 1 and 0 binary form depending on the presence or absence of the DNA band (Caetano-Annolles and Gresshoff, 1994, Sneath and Sokal, 1973). The similarities and differences of the isolates were calculated based in the binary matrix using the simple matching coefficient of the SPSS software (www.spss.com) (Sneath and Sokal, 1973). The Unweighted Pair Group Mathematical Analysis (UPGMA) was used to generate the dendrograms based on (average linkage) and (single average, nearest neighbor) procedure as defined by Caetano-Annolles and Gresshoff, 1994, Sneath and Sokal, 1973, and Demeke and Adams (1994) were used to generate the dendrograms.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation, characterization, and detection of antimicrobial activity

During a survey on the dominant white and gray aerial mycelium-bearing Streptomyces biota in soils of Northern Jordan, 177 different Streptomyces isolates were recovered and characterized. Based on their antimicrobial activity, results indicated that 58 isolates were active against one or both tested bacteria and were distributed as 36 and 22 white and gray active isolates, respectively (Table 2).

3.2. Phenotypic relatedness to RAPD profile

All of the active 58 soil Streptomyces isolates showing an inhibition zones of 18 mm or more were further phenotypically characterized (Table 3) then genetically identified by the analysis of their RAPD fingerprints using five arbitrary primers. Each RAPD experiment was repeated three times with each primer and consistent results were obtained. Based on that, typing scheme as reported by Arbeit (1994) was evaluated to be good, since the five primers showed good typeability, reproducibility and discrimination between the tested isolates.

Table 3.

Phenotypical characterization of the white and gray antibiotic active-producing Streptomyces isolates.

| Color Series |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Gray | Total | |

| No. of Isolates | 36 (62)a | 22 (38) | 58 (100) |

| Pigment Production | |||

| Reverse Side | 31 (83) | 17 (77) | 48 (82) |

| Soluble | 10 (28) | 4 (18) | 14 (24) |

| Melanin | 6 (17) | 3 (14) | 9 (16) |

Percentages between parentheses.

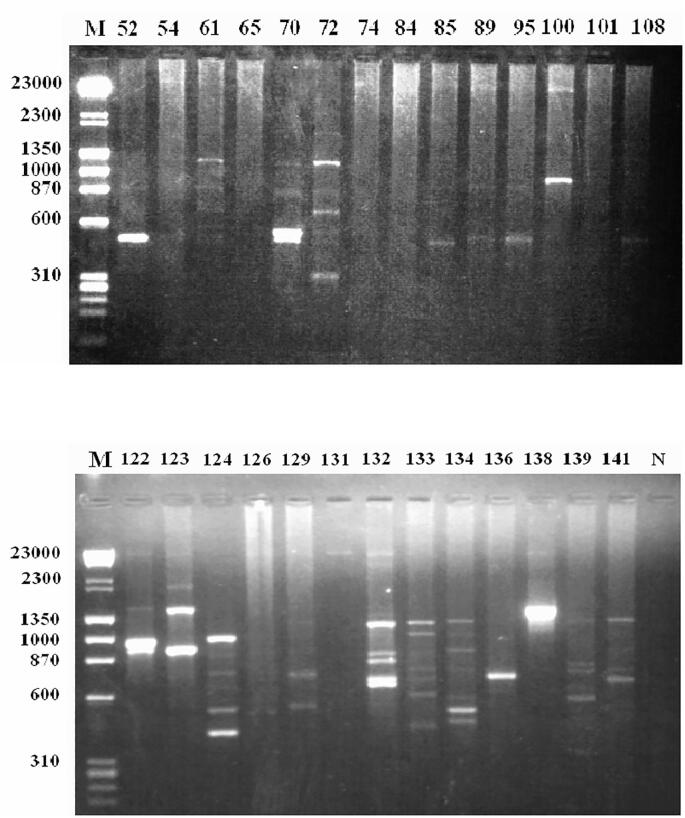

The relatedness among the Streptomyces strains was assessed by comparing the RAPD patterns produced by each primer. This comparison indicated that the various strains differed in the number of polymorphic bands (between 1 and 10) and size that ranged from 200 to 3200 bp (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b, Fig. 1c, Fig 1d, Fig 1e). Several bands were common among the tested isolates but there was one common band (600 bp) that appeared among 85% of the tested isolates (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b, Fig. 1c, Fig 1d, Fig 1e). In addition, 12 DNA bands ranged in size between 600 and 1350 bp were detected as the most common bands among the different isolates for each random primer used. Table 4 shows the size of these bands, the isolate being belonged to, and the primer that generates this band. Moreover, bands specific to some reference strains were also observed.

Fig. 1a.

RAPD fingerprints profile of Streptomyces isolates, on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, amplified using primer OPA02. Lane M: HindIII/Φ x-Hae III molecular weight maker; N: PCR negative control; Lanes correspond to numbers in Table 1.

Fig. 1b.

RAPD fingerprints profile of Streptomyces isolates, on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, amplified using primer OPA08. Lane M: HindIII/Φ x-Hae III molecular weight maker; N: PCR negative control; Lanes correspond to numbers in Table 1.

Fig. 1c.

RAPD fingerprints profile of Streptomyces isolates, on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, amplified using primer OPA09. Lane M: HindIII/Φ x-Hae III molecular weight maker; N: PCR negative control; Lanes correspond to numbers in Table 1.

Fig 1d.

RAPD fingerprints profile of Streptomyces isolates, on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, amplified using primer OPA10. Lane M: HindIII/Φ x-Hae III molecular weight maker; N: PCR negative control; Lanes correspond to numbers in Table 1.

Fig 1e.

RAPD fingerprints profile of Streptomyces isolates, on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, amplified using primer OPA18. Lane M: HindIII/Φ x-Hae III molecular weight maker; N: PCR negative control; Lanes correspond to numbers in Table 1.

Table 4.

The most common 12 DNA bands among the different isolates for each random primer used.

| Serial No. | Band (clone) No. | Size (bp) | Isolate | Primer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | 1350 | H116 | OPA02 |

| 2 | 55 | 870 | C15 | OPA08 |

| 3 | 44 | 870 | B10 | OPA09 |

| 4 | 20 | 600 | J133 | OPA09 |

| 5 | 56 | 870 | J17 | OPA10 |

| 6 | 42 | 1350 | H19 | OPA10 |

| 7 | 35 | 1350 | C12 | OPA10 |

| 8 | 48 | 1350 | S13 | OPA18 |

| 9 | 57 | 870 | A39 | OPA18 |

| 10 | 58 | 1000 | S144 | OPA18 |

| 11 | 50 | 1000 | HA6 | OPA10 |

| 12 | 2 | 1000 | 21g | OPA18 |

UPGMA dendrograms were generated from the fingerprints produced from each primer. The dendrogram shown in Fig. 2 was based on joining the proximity matrices of the three primers into one matrix and obtaining the average of three proximity readings collected from each primer (Mangin et al., 1999). The dendogram (Fig. 2) shows that the tested isolates dropped into two equal super clusters (50% each) (Table 5). Super cluster I appeared to be homogenous and include the three reference strains. However, super cluster II was heterogeneous and but not including any of the reference strains. Super cluster I consists of two clusters (1 and 2). Cluster 1 includes 28% of the isolates in addition to Streptomyces lividans ATCC 35287. Cluster 2 includes 22% of the isolates in addition to S. halestedii ATCC 10897 and S. violaceoruber ATCC 3355. Super cluster II consists of two clusters. The first cluster (cluster 3) includes 15.5% of the tested isolates. The second cluster (cluster 4) includes 34.5% of the tested isolates and by itself consists of three sub-clusters representing the least similarity among other sub-clusters.

Fig. 2.

UPGMA dendrogram derived from the combination of primers OPA02, OPA08, OPA09, OPA10 and OPA18 patterns. Numbers correspond to numbers in Table 1.

Table 5.

Phenotypical characteristicsa of the RAPD clusters members. The reference strains were not included.

| RS | DP | MP | AM | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | N | + | − | + | − | W | G | ||

| Super Cluster I (50%)b | |||||||||

| Cluster 1 | 14 24.5% |

2 3.5% |

4 7% |

12 21% |

3 5% |

13 23% |

10 17.5% |

6 10.5% |

16 (28%) |

| Cluster 2 | 10 17% |

3 5% |

3 5% |

10 17% |

2 3.5% |

11 18.5% |

8 13.5% |

5 8.5% |

13 (22%) |

| Super Cluster II (50%) | |||||||||

| Cluster 3 | 8 14% |

1 1.5% |

2 3.5% |

7 12% |

0 0% |

9 15.5% |

6 10.5% |

3 5% |

9 (15.5%) |

| Cluster 4 | 16 27.5% |

4 7% |

5 8.5% |

15 26% |

4 7% |

16 27.5% |

12 20.5% |

8 14% |

20 (34.5%) |

RS: Reverse side pigment; DP: Diffusible pigment; MP: Melanin pigment; AM: Aerial mycelium color; D: Distinctive; N: Non distinctive; +: Produced, −: Not produced; W: White; G: Gray.

Numbers in parenthesis represent the percent out of the total.

The data determined that when RAPD clustering was compared to phenotypical properties; most of the isolates within cluster 1 and 2 of super cluster I were unable to produce diffusible (21%, 17%) or melanin pigments (23%, 18.5%). However, they were able to exhibit distinctive reverse color (24.5%, 17%) (Table 5). Yet 17.5% and 10.5% of the isolates within cluster 1 of super cluster I, and 13.5% and 8.5% of the isolates within cluster 2 of super cluster I showed white and gray aerial mycelium color, respectively (Table 5). In the case of super cluster II, data showed similar trend to super cluster I, where most of the isolates within cluster 3 and 4 showed un ability to produce diffusible pigments (12%, 26%) or melanin pigments (15.5%, 27.5%). However, they were able to exhibit distinctive reverse color (14%, 27.5%) (Table 5). Data indicated that 10.5% and 5% of the isolates within cluster 3, and 20.5% and 14% of the isolates within cluster 4 showed white and gray aerial mycelium color, respectively (Table 5).

When the antibiotic activity of all dominant white and gray aerial mycelium-bearing Streptomyces isolates where compared to RAPD clustering, results revealed that the dominant white and gray isolates where interestingly divided by 50% in each super-cluster with 16.38% and 16.39% of the isolates were active against both tested bacterial pathogens in super-cluster 1 and II, respectively (Table 6). However, when this activity was compared to the different clusters, data indicated that most of the dominant white and gray isolates belong to cluster 4 of super-cluster II (11.3%), and least abundant belong to cluster 3 (5.08%) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Distribution of antibiotic activity of all dominant white and gray aerial mycelium-bearing Streptomyces isolates when compared to RAPD clustering.

| S. aureus | E. coli | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Gray | White | Gray | ||

| Super Cluster I (50%) | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 14.09% | 8.26% | 8.60% | 2.38% | 9.18% |

| Cluster 2 | 10.87% | 6.37% | 6.95% | 1.93% | 7.21% |

| Total | 24.96% | 14.63% | 15.55% | 4.31% | 16.39% |

| Super Cluster II (50%) | |||||

| Cluster 3 | 8.46% | 4.96% | 4.03% | 1.14% | 5.08% |

| Cluster 4 | 16.51% | 9.68% | 11.45% | 3.18% | 11.30% |

| Total | 24.97% | 14.64% | 15.48% | 4.32% | 16.38% |

4. Discussion

Testing of the antimicrobial activity of the recovered 177 white and gray Streptomyces isolates resulted in identification of 58 active-producing isolates with more potential for the white isolates than gray one and mainly towards S. aureus. Morphological characterization of these 58 active isolates revealed that the white isolates tend to be more producers to the three pigments; reverse side, soluble, and melanin, than the gray isolates. RAPD profiles for the 58 antibiotic-producing Streptomyces strains along with three reference strains were evaluated by UPGMA dendrograms. This analysis provided a simultaneous sequence comparison between these isolates.

When the band patterns of this study were compared to the patterns obtained by Garaibeh et al. (2003), data revealed that the number of polymorphic bands generated for each isolate was between 1 and 10 with a size ranged between 200 and 3200 bp as compared to 1 and 18 with a size ranged between 250 and 2777 bp obtained by Garaibeh et al. (2003). This study revealed only one common band of 600 bp shared by approximately 85% of the tested isolates compared to three common bands of 2777, 800 and 250 bp shared by approximately (95%) of the isolates that were reported by Garaibeh et al. (2003). This difference between the two studies in band numbers, profile and even the size could be due to the location of isolation being restricted to the most humid and vegetative part of Jordan, or to that the analysis applied here is confined to only two color aerial mycelia groups (white and gray) of Streptomyces isolates, or to the use here of more primers in RAPD analysis. Our results are also different from what was reported by Malkawi et al., 1999, Saadoun and Gharaibeh, 2003, Mehling et al., 1995; or Saadoun et al. (2007) as a result of using different analysis conditions like the thermo-stable DNA polymerase, thermo-cycler machine, and PCR reagents (Caetano-Annolles and Gresshoff, 1994, Power, 1996).

Five arbitrary primers were used to conduct the RAPD-PCR amplification, these primers showed the existence of common bands between all the isolates and the reference strains, which may indicate possible Streptomyces-probes. Upon each RAPD-PCR run, results were consistent or reproducible, and the primers also showed good typeability and the power of discrimination according to Arbeit (1994). Despite the less number of arbitrary primers used by Malkawi et al. (1999) and Garaibeh et al. (2003), the results reported here are in agreement with what was reported by both studies Malkawi et al. (1999) and Garaibeh et al. (2003) about the potential of these primers to discriminate soil Streptomyces isolates from Jordan. However, these studies did not include the RAPD-PCR fingerprints analysis for the dominant occurrence of the antibiotic-producing white and gray aerial mycelia bearing streptomycetes.

Associating the RAPD fingerprints of the antibiotic-producing white and gray Streptomyces isolates to their phenotypes resulted in the differentiation between the isolates of cluster 1 (24.5%) and cluster 2 (17%) of super cluster I and between the isolates of cluster 3 (14%) and cluster 4 (27.5%) of super cluster II. This association is explained, as most of the isolates were distinctive-reverse side pigment producers, while few isolates of all clusters in both super clusters were non-distinctive-reverse side pigment producers. This suggests the possibility of the primers used here in this study to amplify distinctive-reverse side pigment production genes. These findings are unlike what Garaibeh et al. (2003) found when they suggested the possibility of the primers used in their study to amplify melanin pigment production genes. Other phenotypic characteristics of the melanin and diffusible pigments along with the antibiosis profile of the isolates didn’t produce reasonable clustering information as most of the isolates in super cluster I and II were melanin-negative (41.5% and 43%) and equally (38% each) to be unable to produce diffusible pigments.

5. Conclusion

This investigation indicated for the first time the association of the antibiotic activity of the dominant white and gray aerial mycelium-bearing Streptomyces isolates to RAPD clustering. As the number of random primers used in RAPD analysis increased, the technique expected to be cost-effective, fast, precise, and less labor work solution for molecular analysis of the Streptomyces isolates.

6. Ethical disclosures

The authors announce that no experiments were performed on animals and no data were collected from patient in this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Jordan University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 70/2003) funded this research. Appreciation is extended to University of Sharjah/UAE for administrative support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Amjad A. Mahasneh, Email: amajada@just.edu.jo.

Jazi D. Odat, Email: jazi31@yahoo.com.

Ban M. Al-Joubori, Email: baljoubori@sharjah.ac.ae.

Ismail Saadoun, Email: isaadoun@sharjah.ac.ae.

References

- Abussaud M., Saadoun I. Streptomyces flora of some Jordan Valley soils, characteristics and seasonal distribution. Dirasat. 1991;18B(3):66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeit T.L. Laboratory procedures for epidemiological analysis. In: Murray P.R., Barn E.J., Pfaller M.A., Tenover F.C., Yolher R.H., editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 6th ed. ASM Press; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A.W., Kirby W.M., Sherris J.C., Turk M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disc method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyazova M., Lechvalier M. Taxonomic utility of restriction endonuclease fingerprinting of larg DNA fragments from Streptomyces strains. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1993;43:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Annolles G., Gresshoff P.M. DNA amplification using arbitrary minihairpin oligonucleotide primers. BioTech. 1994;12:619–623. doi: 10.1038/nbt0694-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhou D., Qi D., Gao Z., Xie J., Luo Y. Growth promotion and disease suppression ability of a Streptomyces sp. CB-75 from banana rhizosphere soil. Front. Microbiol. 2018;8:2704. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeke T., Adams R.P. The use of PCR-RAPD analysis in plant taxonomy and evolution. In: Griffin H., Griffin A., editors. PCR Technology: Current Innovations. CRC Press; London: 1994. pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- El-Tarabily K.A., AlKhajeh A.S., Ayyash M.M., Alnuaimi L.H., Sham A., ElBaghdady K.Z., Tareq S., AbuQamar S.F. Growth promotion of Salicornia bigelovii by Micromonospora chalcea UAE1, an endophytic 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid deaminase-producing actinobacterial isolate. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1694. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Tarabily K.A., ElBaghdady K.Z., AlKhajeh A.S., Ayyash M.M., Aljneibi R.S., El-Keblawi A., AbuQamar S.F. Polyamine-producing actinobacteria enhance biomass production and seed yield in Salicornia bigelovii. Biol. Fertil Soils. 2020;56:499–519. doi: 10.1007/s00374-020-01450-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garaibeh R., Saadoun I., Mahasneh A. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of antibiotic-producing soil Streptomyces investigated by RAPD-PCR. J. Basic. Microbiol. 2003;43:18–27. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200390000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopowood D.A., Bibb M.J., Chater K.F., Kieser T., Bruton C.J., Kieser H.M., Lydiate D.J., Smith C.P., Schrempf H. John Innes Foundation. Norwich; United Kingdom: 1985. Genetic Manipulation of Streptomyces: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Janardhan A., Kumar A.P., Viswanath B., Saigopal D. Production of bioactive compounds by actinomycetes and their antioxidant properties. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2014;2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/217030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamil F.H., Saeed E.E., El-Tarabily K.A., AbuQamar S.F. Biological control of Mango Dieback disease caused by Lasiodiplodia theobromae using Streptomycete and non-streptomycete actinobacteria in the United Arab Emirates. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:829. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L.R., Tazeng D.D., Yang C.H. Generation of PCR-based DNA fragments for specific detection of Streptomyces saraceticus N45, Proc. Nation. Sci. Counc. Repub. China Part B. 2001;2:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küster E., Williams S. Selection media for the isolation of streptomycetes. Nature. 1964;202:928–929. doi: 10.1038/202928a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebada D. DNA relatedness among strains of Streptomyces lavendulae phenotypic cluster group. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1993;43:822–825. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu J., Díaz-Cruz G., Cheng Z. Virulence mechanisms of plant-pathogenic Streptomyces species: an updated review. Microbiol. 2019;165(10):1025–1040. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkawi H.I., Saadoun I., Moumani F., Meqdam M.M.M. Use of RAPD-PCR to detect genetic diversity of soil Streptomyces isolates. New Microbiol. 1999;22:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangin I., Corroler D., Reinhardt A., Gueguen M. Genetic diversity among diary lactococcal strains investigated by polymerase chain reaction with three arbitrary primers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1999;86:514–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., Dary A., Decaris B. Identification and typing of Streptomyces strains: evaluation of interspecific, intraspecific and intraclonal differences by RAPD fingerprinting. Res. Microbiol. 2000;151:853–864. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)01152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, B.T., Torky, T., Amin, A., Mourad, A., HI., Ayyash, M.M. El-Keblawy, A., Alnaqbi, A.H., AbuQamar, S.F., El-Tarabily, K.A., 2020. Halotolerant marine rhizosphere-competent actinobacteria promote Salicornia bigelovii growth and seed production using seawater irrigation. Front. Microbiol. 11, 552. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mehling A., Wehmeier U.F., Piepersberg W. Application of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) assays in identifying conserved regions of actinomycete genomes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995;128:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi K. A taxonomic study of the genus Streptomyces by analysis of ribosomal protein AT-L30. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1995;45:507–514. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-3-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odat J. Jordan University of Science and Technology; Jordan: 2004. Molecular characterization of the antibiotic-producing Streptomyces species by cloning of species-specific DNA markers. M.Sc. Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Power E.G.M. RAPD typing in microbiology – a technical review. J. Hospital Infect. 1996;34:247–265. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(96)90106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M.A., Crawford D.L. Use of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA as a means of developing genus- and strain-specific Streptomyces DNA probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:2555–2564. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2555-2564.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Al-Momani F. Streptomycetes from Jordan soils active against Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Actinomycetes. 1997;8:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun, I., AL-Momani, F., 1997b. Studies on soil streptomycetes from Jordan, Actinomycetes 8, 42–48.

- Saadoun I., Mohammad M.J., Malkawi H., Al-Momani F., Meqdam M. Diversity of soil streptomycetes in Northern Jordan. Actinomycetes. 1998;9(3):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Al-Momani F., Malkawi H., Meqdam M., Mohammed M. Isolation, identification and analysis of antibacterial activity of soil streptomycetes from North Jordan. Microbios. 1999;100:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Hameed K., Al-Momani F., Malkawi H., Meqdam M., Mohammad M.J. Characterization and analysis of antifungal activity of soil streptomycetes isolated from North Jordan. Egypt. J. Microbiol. 2000;35:463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Gharaibeh R. The Streptomyces flora of Jordan and its’ potential as a source of antibiotics active against antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, World. J. Microbiol. Biotech. 2002;18:465–470. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Gharaibeh R. The Streptomyces flora of Badia region of Jordan and its’ potential as a source of antibiotics active against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. J. Arid Environ. 2003;53(3):365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Rawashdeh R., Dayeh T., Ababneh Q., Mahasneh A. Isolation, characterization and screening for fiber hydrolytic enzymes-producing streptomycetes of Jordanian forest soils. Biotechnol. 2007;6(1):120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Wahiby L., Ababneh Q., Jaradat Z., Massadeh M., Al-Momani F. Recovery of soil streptomycetes from arid habitats in Jordan and their potential to inhibit multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogens. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;24:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun I., Ananbeh H., Ababneh Q., Jaradat Z. Comparative distribution of soil Streptomyces flora in different Jordanian habitats and their enzymatic and antibiotic activities. Res. J. Phrarm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2017;8(2):1285–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, E.E., Sham, A., Salmin, S., Abdelmowla, Y., Iratni, R., El-Tarabily, K.A., AbuQamar, S.F., 2017. Streptomyces globosus UAE1, a potential effective biocontrol agent for black scorch disease in date palm plantations. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1455. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shirling E.B., Gottlieb D. Methods for characterization of streptomycetes species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1966;16:313–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sneath P.H.A., Sokal R.R. W.H. Freeman; San Francisco, USA: 1973. Numerical Taxonomy. [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.T., Goodfellow M., Alderson G., Wellington E.M., Sneath P.H., Sackin M.J. Numerical classification of Streptomyces and related genera. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1983;129:1743–1813. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-6-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.T., Goodfellow M., Wellington E.M., Vickers J.C., Alderson G., Sneath P.H., Sackin M.J., Mortimer A.M. A probability matrix for the identification of some streptomycetes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1983;129:1815–1830. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-6-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.G.K., Kubelik A.R., Livak K.J., Rafalski J.A., Tingey S.V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.-H., Ha S.-M., Kwon S., Lim J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evolution. Microbiol. 2017;67(5):1613–1617. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W.M., Carwford D.L. Characterization of Streptomyces lydicus WYEC 108 as a potential biocontrol agent against fungal root and seed rots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61:3119–3128. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3119-3128.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor; NY, USA: 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; pp. 150–478. [Google Scholar]