Abstract

Smokeless tobacco habits are detrimental to oral health. A correlation between tobacco use and local epithelial tissue damage exists. Yet, the underlying cellular mechanism is not precisely characterized. This study assessed the dose-dependent action of Smokeless tobacco extract on gingival epithelial cells. Gingival tissue was taken from 5 healthy donors. Gingival epithelial cells were isolated by an enzymatic method and cultured up to passage 2. The cultured cells were treated with smokeless tobacco extract at 10%, 25%, 50%, and 75% volume concentration. After 48 h of incubation, MTT assay, Annexin V/PI assay, and DiIC1(5) assay were used to evaluate viability, apoptosis, and mitochondrial potential of the cells. RT-qPCR was used to determine the expression of BAX, BCL2, ECAD, NCAD, and TWIST. The Smokeless tobacco extract reduced cell viability by disrupting the mitochondrial potential and inducing apoptosis. Further, the Smokeless tobacco extract induced a dose-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal-transition in gingival epithelial cells. Apoptotic cellular death caused by tobacco extract on the gingival epithelial system was dependant on the mitochondrial potential of the cell. The results demonstrate that smokeless tobacco causes detrimental metabolic alterations of the periodontium.

Featured application

This study elucidates the mechanism by which Smokeless tobacco products cause cellular damage to the gingival epithelium. The use of Smokeless tobacco products can lead to major cellular and surface changes in the gingiva and its appearance. The consequences of these changes are not limited to oral cancer but also increases a person’s risk for dental and periodontal disease.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Gingival epithelial cells, Mitochondrial potential, Smokeless tobacco

1. Introduction

Combating the scourge of tobacco is one of the great public health challenges of the 21st century. Tobacco use is estimated to lead to 8 million deaths a year (Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2020, 2020). Countries across the world have enacted public health measures to encourage people to quit smoking. However, Smokeless Tobacco (ST) products appear to enjoy rising popularity. Smokeless tobacco is replacing cigarettes in parts of the world (Sinha et al., 2015, Suliankatchi et al., 2019). Studies have proposed a shift to ST use as having less harmful effects compared to smoking (Savitz et al., 2006). This boom in smokeless tobacco use could signal the beginning of a ST based epidemic. The use of ST products is linked to an increased risk of oral cancer worldwide (Asthana et al., 2019). ST refers to a broad range of products such as snuff (moist, dry, snus) and smokeless tobacco (plug, loose leaf, twist, dip) that are consumed by sniffing or chewing rather than smoking. They are placed in the oral and nasal cavities. Smokeless Tobacco is either chewed or placed on the inside of the lip, under the gums, or in between the cheeks and gums. The placement in mucosal cavities allows nicotine absorption. The use of ST products can lead to the development of tolerance over time. This causes the user to consume more to achieve the same effect. Smokeless tobacco is addictive and users show signs of dependency and withdrawal (Henningfield et al., 1997).

The use of ST products is believed to have led to a rise in the incidence of oral cancer across the world (Alsanosy, 2014, Walsh and Epstein, 1996, Warnakulasuriya, 2004). Several clinico-epidemiological studies have linked tobacco as a chewing or sniffing material to the higher incidence of oral cancer in South Asian populations (Alsanosy, 2014, Cheong et al., 2017). Globally, South Asia accounts for 90% of the liability of smokeless tobacco (Awan and Patil, 2016). In South Asian countries, where smoking is seen as a taboo, ST has no such stigma attached to it and its use is seen across various demographics - in children, teenagers & women (Dobe et al., 2006).

The prevalence of oral cancer is high in South Asia (Krishna Rao et al., 2013). Oral cancer represents 10.4% of all malignant diseases globally. It occupies the eighth position in the rank order of relative incidences of all cancers (Amer et al., 1985). Histopathological and molecular data strongly suggest that substances in ST are carcinogenic (Chaffee et al., 2016, Hecht, 2003, Hecht and Hoffmann, 1988, Hoffmann and Djordjevic, 1997). They include but are not limited to N-nitrosamine, N-nitrosamino acids, volatile aldehydes, volatile tobacco-specific nitrosamines, and polynuclear agents (Stepanov et al., 2005). Oral premalignant disorders associated with smokeless tobacco include periodontal disease, leukoplakia, impaired wound healing, and dental caries (Walsh and Epstein, 1996)(Boffetta et al., 2008).

The higher incidence of oral cancer in South Asia has been extensively investigated. However, there is a lack of data, particularly in terms of well-designed in vitro cellular studies. Most in vitro studies were performed on the oral mucosal epithelial cells and keratinocytes (Amer et al., 1985, Bhat et al., 2018, Johnson, 2001, Nanjappa et al., 2015). Oral Squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a common subtype of oral cancer (Bettendorf et al., 2004). Effects of ST products on the gingival epithelium and their relationship with the initiation of OSCC are not well characterized in the literature. Previous studies established the initiation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during the process of malignant progression (Zhang and Weinberg, 2018). However, investigations to date are unable to link apoptosis, loss of mitochondrial potential, and EMT in damage to the gingival epithelial architecture. There is a need to incontrovertibly establish the mechanisms responsible for cellular damage occurring before the initiation of cancer. The present study investigated the effects of an aqueous Smokeless Tobacco Extract (STE) exposure on gingival epithelial cells to partly fill the lacunae in studies to date.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

Gingival tissue samples were collected from 13 periodontally healthy participants with proper oral hygiene. The participants were scheduled for extraction for orthodontic treatment. The tissues were ~ 3 mm X 3 mm in size. Informed consent was obtained per institutional ethics considerations. The samples were collected in a sterile container containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1X) and immediately transported to the laboratory for further processing.

2.2. Gingival epithelial cells (GECs) isolation and culture

The gingival epithelial cells were isolated as described in the literature.36,37 The gingival tissues were exposed to the enzyme solution containing Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 2 mg/mL Dispase II (Roche Diagnostics, Roche Applied Science, Germany) for 5 min to remove the epithelial part of the tissue. The separated epithelial tissue was minced and incubated for 20 min in the same enzyme cocktail previously mentioned. After incubation, fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) was used to neutralize the enzymatic action. The mixture was centrifuged at 1800 rpm for 5 min. The count was taken and approximately 2 X 105 cells were yielded from each sample. The pellet of cells obtained was resuspended and cultured in Keratinocyte SFM (1X) (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in 6-well plates. After 3 days, the cells started to attach to the surface of the culture plates. After that, the media was replaced with fresh medium every alternate day. On the 8th day of culture, the cells become confluent in the culture wells. The confluent cells were split in a 1:2 ratio and expanded further. Cells from passage 2–4 were used for the experiments.

2.3. Preparation of STE and treatment to the cells

Smokeless tobacco was obtained from a local supplier (Afzal Pandarpuri, Sopariwala Exports, Mumbai, India). 10 g of tobacco was finely powdered and mixed with 100 ml of sterile water.(Lallier et al., 2017) The mixture was kept on a shaker overnight at room temperature. After 24 h, the mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant was collected in a sterile tube. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22-µm syringe filter (Corning, NY, USA). The stock solution was diluted using a complete medium to achieve concentrations of 10%, 25%, 50%, and 75% of STE. The medium was kept at uniform volume for all the treatment groups to meet their nutritional requirement.

2.4. MTT assay to assess cell viability

The viability of the cells was evaluated using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide).(Li et al., 2018) The cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells per well) and incubated with a complete medium for 24 h. After the adhesion of the cells to the bottom of the wells, the spent medium was replaced and the cells were subjected to the treatment with various concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) for 48 h. Cells without STE treatment served as a control group. After treatment, the untreated (control) and treated cells were harvested and a solution of 0.5 mg/ml of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) was introduced per well. The plates were incubated for 3 h. Post-incubation, the medium in each well was replaced with 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A spectrophotometer (Multiskan FC, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to read the absorbance at 570 nm.

2.5. Apoptosis detection assay using Annexin V-FITC/PI staining on a flow cytometer

Apoptosis was analyzed using Annexin V-FITC/PI staining (BD Pharmingen, USA).(Bagchi et al., 1999, Li et al., 2018) The cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) and incubated with a complete medium for 24 h. After the adhesion of the cells to the bottom of the wells, the spent medium was replaced. The cells were subjected to the treatment with various concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) for 48 h. Cells without STE treatment served as a control group. The untreated (control) and treated cells were harvested and stained with Annexin V-FITC reagent. The cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the absence of light. After incubation, PI reagent was introduced to the cells and immediately assayed by flow cytometry (Attune NxT, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, the percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated.

2.6. Detection of mitochondrial potential by flow cytometry

MitoProbe DiIC1(5) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to detect mitochondrial membrane potential in treated and untreated cells.(Sivandzade et al., 2019) DiIC1(5) gathers in eukaryotic mitochondria with respect to mitochondrial membrane potential. The cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) and incubated with a complete medium for 24 h. After the adhesion of the cells to the bottom of the wells, the spent medium was replaced and the cells were subjected to the treatment with various concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) for 48 h. Cells without STE treatment served as a control group. The untreated (control) and treated cells were harvested and the cells were stained with 10 µM of 1,1′,3,3,3′,3′-hexamethylindodicarbo-cyanine iodide (DiIC1(5)). Negative control cells were treated with 50 μM Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), a protonophore mitochondrial toxin, and then incubated at 37 °C at 5% CO2 for 15–30 min to induce apoptosis. Post incubation, the cells were washed with PBS (1X) before they were analyzed using a flow cytometer. The data was calculated as median fluorescence intensity (MFI).

2.7. Assessment of apoptosis- and EMT-related genes by RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to examine the expression of BAX, BCL2, ECAD, NCAD, and TWIST. The cells were seeded in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) and incubated with a complete medium for 24 h. After the adhesion of the cells to the bottom of the wells, the spent medium was replaced and the cells were subjected to the treatment with various concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) for 48 h. Cells without STE treatment served as a control group. The untreated (control) and treated cells were harvested and extraction of total RNA from the cells was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (GeneJet, Thermo Scientific, Lithuania). Reverse transcription of 1 µg of total RNA was carried out with cDNA synthesis kit (High Capacity, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative analyses of gene expressions were done using SYBR® Green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems™, Austin, TX, USA) in QuantStudio™ 5 RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems™, USA). Normalization of the target gene expression to β-actin (ACTB) was done using ΔΔCT method. CT values were evaluated using the mean cycle threshold value. 2-ΔΔCT methodology was implemented for the quantification of RT-PCR data. The displayed relative gene expressions were compared between the groups. The primers used (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA) are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The experimentations previously described were performed thrice. All samples were run as triplicates. Mean and standard deviation was used to represent the data with thirteen independent samples. The statistical significance between the experimental groups was determined by paired two-tailed student’s t-test. P-values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant and ≤ 0.01 was considered highly significant.

3. Results

3.1. STE decreased cell viability with increasing concentrations.

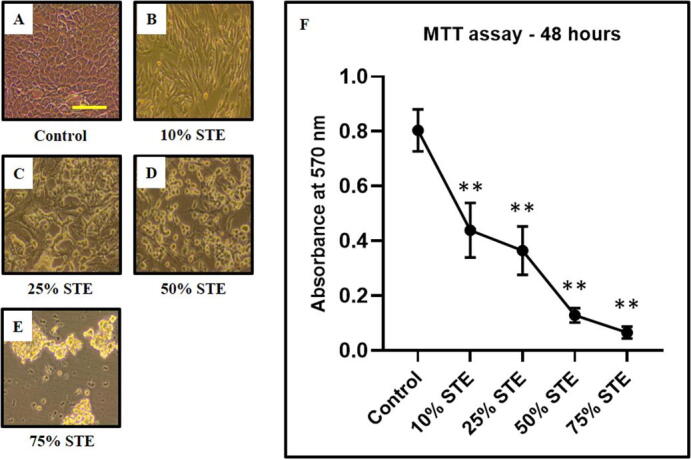

The MTT assay revealed that higher concentrations of STE highly correlated with cellular death. This was also observed in the microscopic photographs of GECs with and without treatment (Fig. 1A-1E). A significant loss of viability is seen in GECs treated with higher concentrations of STE. No significant change was seen in the lowest concentration of 10% STE. The graph in Fig. 1 shows the results of the MTT assay depicting the decreasing viability of the GECs with increasing STE treatment (Fig. 1F).

Apoptosis is induced by STE in a concentration dependant manner

Fig. 1.

A single-cell suspension was prepared from the gingival epithelium. In-vitro culture-expanded cells (GECs) were treated with smokeless tobacco extract (STE) at varying concentrations for 48 h and an MTT assay was performed to assess cell viability. (A-E) Representative photomicrographs of GECs (obtained from 1 sample out of 13 samples) were treated with different concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%). Scale bar = 100 µm, (F) Comparative MTT assay showing decreasing metabolic activity/viability with increasing concentration of STE. The results represent the mean of all 13 experimental values and standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns not significant. STE: smokeless tobacco extract.

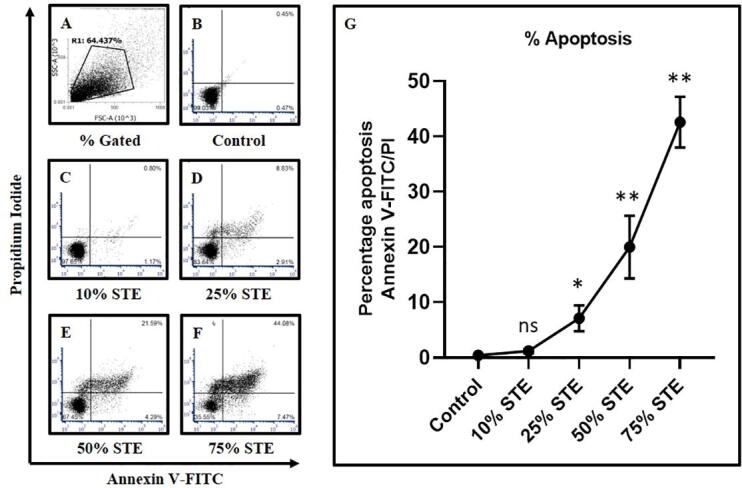

Annexin V/PI assay by flow cytometry for the detection of apoptosis revealed that the higher concentrations of 50% and 75% of tobacco prompted highly induced apoptosis in GECs. (Fig. 2E, 2F, & 2G) No significant change was seen in the lowest concentration of 10% tobacco extracts (Fig. 1C & 1G).

Fig. 2.

GECs were treated with STE at varying concentrations for 48 h and apoptosis was assessed by Annexin V-FITC/PI assay. (A-F) Representative dot plots for apoptosis detection in GECs (obtained from 1 sample out of 13 samples) treated with different concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) for 48 h, and harvested cells were subjected to annexin V/PI staining for acquisition on a flow cytometer. (G) Comparative analysis of percentage apoptosis in GECs treated with varying concentrations of STE. The results represent the mean of all 13 experimental values and standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns not significant. STE: smokeless tobacco extract.

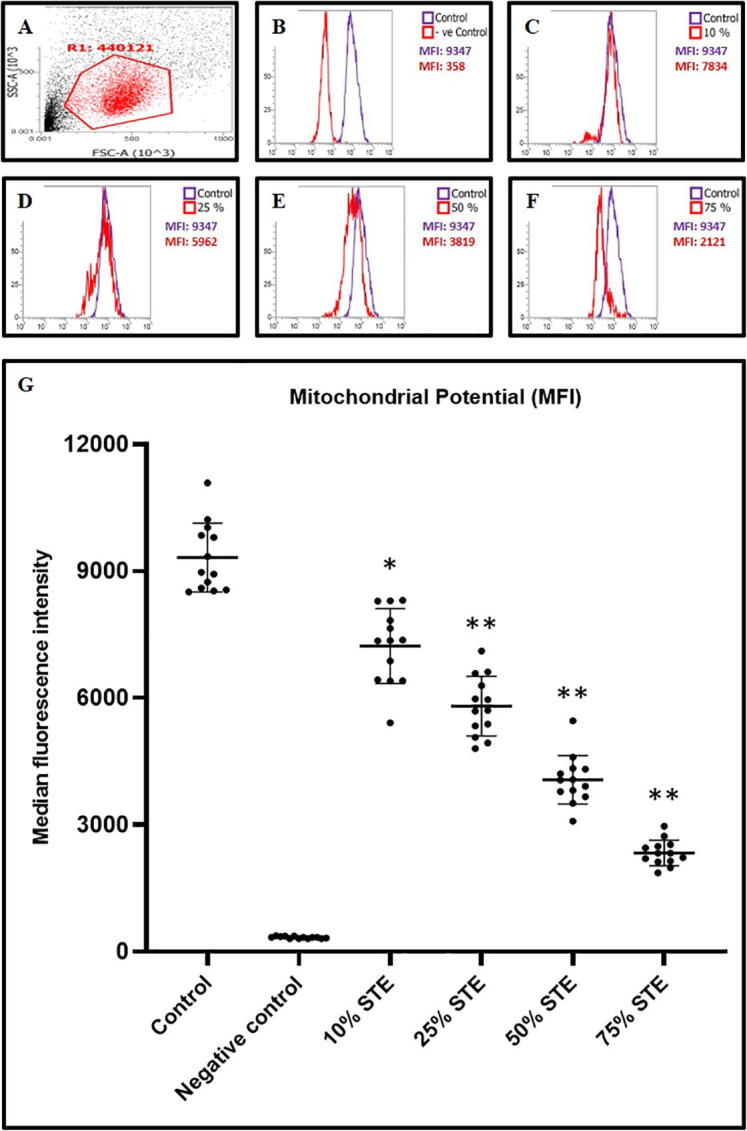

3.2. Mitochondrial membrane potential decreases with treatment using a higher concentration of STE

Increasing concentrations of STE led to concurrent decreases in the mitochondrial potential of GECs (Fig. 3A-3G). The decrease in the mitochondrial potential is depicted in Fig. 2 (Fig. 3G). No significant change was seen in the mitochondrial potential of GECs treated with 10% concentration of tobacco extract i.e., lowest concentration (Fig. 3C & 3G).

Fig. 3.

GECs were treated with STE at varying concentrations for 48 h and mitochondrial potential (fluorescence intensities) was assessed by DiIC1(5) staining assay. Untreated cells served as control and CCCP induced apoptotic cells served as a negative control. (A-F) Representative dot plot for gating and histograms for mitochondrial potential in GECs (obtained from 1 sample out of 13 samples) treated with different concentrations of STE (10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%) for 48 h and harvested cells were subjected to DiIC1(5) staining for acquisition on a flow cytometer. (G) Comparative analysis of median fluorescence intensities (MFI) in GECs treated with varying concentrations of STE and subjected to DiIC1(5) staining. The results represent the mean of all 13 experimental values and standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns not significant. STE: smokeless tobacco extract.

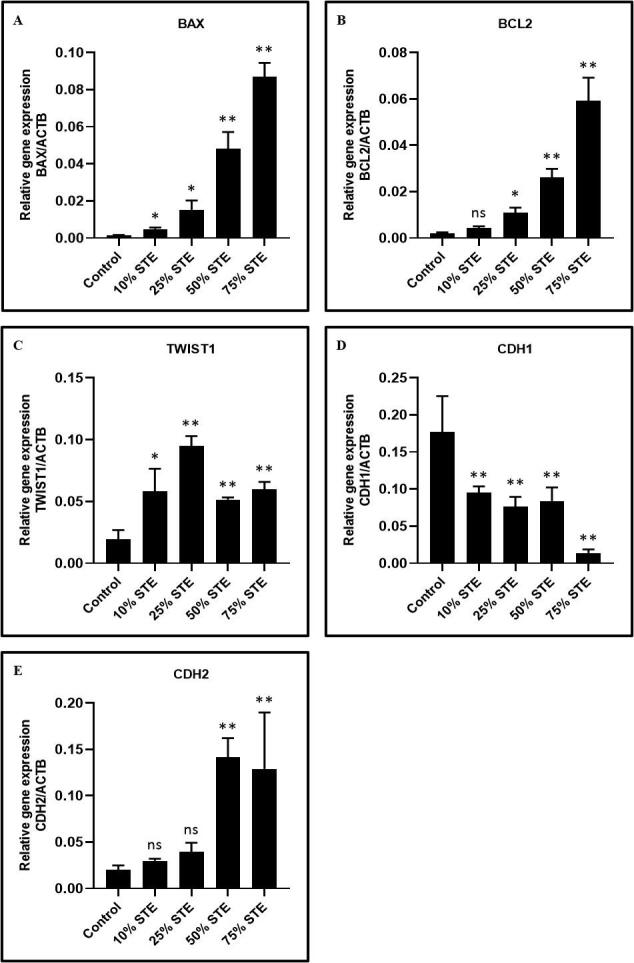

3.3. Expression of genes related to apoptosis and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) increases with the higher concentrations of tobacco extract

The analysis of the percentage apoptosis in GECs treated with various concentrations of STE is depicted in Fig. 4. The expression of apoptosis-related genes BCL2 and BAX increases in a concentration dependant gradient after treatment with STE (Fig. 4A & 4B). Treatment with 10%, 25%, 50%, and 75% STE showed significantly high levels of BAX (Fig. 4A). Similarly, treatment with 25%, 50%, and 75% of STE showed significantly higher levels of BCL2 than in the control (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

GECs were treated with STE at varying concentrations for 48 h and relative gene expression analysis of apoptosis and EMT-related genes was performed. GECs were treated with STE for 48 h at concentrations of 10%, 25%, 50%, and 75%. Harvested cells were subjected to total RNA isolation and RT-qPCR was performed to assess the gene expression of apoptosis and EMT-related genes. (A) BAX (Apoptosis regulator BAX), (B) BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), (C) TWIST1 (Twist-related protein 1), (D) CDH1 (E-cadherin), and (E) CDH2 (N-cadherin). The results represent the mean of all 13 experimental values and standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns not significant. STE: smokeless tobacco extract.

Higher concentrations of STE showed a significant decrease in epithelial-related gene E-cadherin (ECAD) (Fig. 4D). Expression of N-cadherin (NCAD), a mesenchymal-related gene, was significantly increased at a concentration of 75% of STE (Fig. 4E). The expression of TWIST rose with an increase in the concentration of STE (Fig. 4C). The highest expression of TWIST was seen at the concentration of 25% of STE.

4. Discussion

Oral cancer is a growing problem around the globe (Johnson, 2001). Its mortality rate is predicated on how early the cancer is detected. Quality of life remains poor for survivors (Warnakulasuriya, 2010). Tobacco remains a potent risk factor contributing to oral cancer. Across the world, tobacco is primarily consumed through smoking. However, in South Asian countries, the use of ST products is common across demographics. ST users may be exposed to a higher amount of carcinogens than cigarette smokers (Boccuzzi, 2014, Printz, 2016, Syed et al., 2009). Earlier studies described how ST use can injure the gingiva leading to loss of marginal gingiva and alveolar dehiscence at sites and focused on oral epithelial cells (Robertson et al., 1990, Weintraub and Burt, 1987). However, few studies have considered the cellular and molecular level changes caused by smokeless tobacco on the gingival epithelium and periodontal damage.

Pathogenesis of several cancers can be affected by altered cellular homeostasis in the oral cavity (Xin et al., 2014). Cellular transformations can vary based on the modality of tobacco consumption. Cellular disturbances in the buccal mucosal epithelium are seen in OSCC patients who report a tobacco-chewing habit (Warnakulasuriya and Ralhan, 2007). Silva et al found that cigarette smoke condensate exerted a cytotoxic effect on gingival cells (Silva et al., 2012). In the present study, we observed similar results. Increasing concentrations of STE showed decreasing cellular viability in GECs.

Flow cytometric measurements were used to assess apoptosis of the treated GECs. The analysis revealed the presence of non-viable GECs that exhibited a range of changes. The percentage of apoptosis increased with a rise in STE concentration. This is consistent with the results of earlier studies by Mangipudy (Mangipudy and Vishwanatha, 1999) and Li et al (Li et al., 2018). Bagchi et al claimed that STE-induced free radicals led to apoptosis in oral keratinocytes. They stated that antioxidants may be able to attenuate concentration-dependent apoptotic cell death (Bagchi et al., 1999).

Numerous studies have found that cigarette smoke can negatively affect mitochondrial respiration and membrane potential (Aravamudan et al., 2014, Fetterman et al., 2017, Hara et al., 2013). A similar result was found in the present study regarding mitochondrial potential. Increasing concentrations of STE caused a concurrent decrease in mitochondrial potential in GECs. The mitochondrial potential was found to be inversely proportional to cellular viability. Decreased mitochondrial potential can result in diminished ATP content and increased oxidant production. This oxidative stress could induce structural abnormalities in mitochondria (Aravamudan et al., 2014, Fetterman et al., 2017, Hara et al., 2013, Hoffmann et al., 2013).

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is a biological process that is vital to embryogenesis, wound healing, etc. (Voulgari and Pintzas, 2009). However, EMT has also been linked to cancer initiation and metastasis (Heerboth et al., 2015). Reversing EMT could prove to be a promising avenue of treatment. Preventing mesenchymal transition that could inhibit metastatic growth. In the present study, increasing concentrations of STE caused the cells to undergo a transition from epithelial to mesenchymal phenotype.

TWIST is a transcription factor and master regulator of EMT. Epithelial cells that overexpress TWIST undergo EMT. An increase in expression of TWIST was observed with increased concentrations of STE. Higher concentrations of STE also caused a significant decrease in epithelial-related gene E-cadherin (ECAD). In epithelial cancers, the loss of E-cadherin expression is seen before EMT. It appears that the decrease in expression of ECAD is crucial for EMT to occur. However, a decrease in ECAD expression solely cannot induce EMT in epithelial cells. Previous studies revealed that elevated TWIST and reduced ECAD can affect and promote the metastatic capacity of tumors (Karreth and Tuveson, 2004).

NCAD is a marker of mesenchymal phenotype. Up-regulation of NCAD is correlated with an increase in cell migration and invasion (Heerboth et al., 2015). In our study, the expression of NCAD was significantly increased in a higher concentration of STE. Downregulation of ECAD and increase in NCAD is a hallmark of EMT and is known as cadherin switching (Nguyen et al., 2011). Cadherin switching occurs during normal biological processes. In cases of OSCC, cadherin switching plays a major role in disease development and progression.

BAX and BCL2 are genes related to apoptosis. In the present study, their expression increased in a dose-dependent manner based on the concentration of STE. BAX and BCL2 work at cross purposes to each other (Toshiyuki and Reed, 1995). BAX accelerates apoptosis whilst BCL2 is a potent anti-apoptotic molecule. The dysregulation of BAX and BCL2 can be oncogenic. Earlier studies reported a correlation between tobacco use and increased expression of BCL2 in oral cancer patients (Mai et al., 2003). BCL2 may be a target of carcinogens found in STE. Dysfunction of the BCL2/BAX apoptosis signaling pathway may have a role in tumorigenesis and tumor progression (Cory and Adams, 2002).

Earlier, it was hypothesized that the use of ST products is less harmful compared to smoking (Lallier et al., 2017, Savitz et al., 2006). Woo S et al (Woo et al., 2017) observed that the aldo–keto reductase genes, AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 (involved in the activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to genotoxic intermediates) were significantly upregulated in gingival epithelial cells exposed to combustible tobacco products, while the effect induced by non-combustible tobacco products on AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 were relatively attenuated. Gao et al (Gao et al., 2014) observed that that DNA damage induced by combustible tobacco products on the gingival epithelial cells was significantly higher compared to the minimal DNA damage induced by the non-combustible tobacco products. The results of the present study lead us to disagree with this characterization.

EMT induction is an aspect of cellular damage in the gingival epithelial system that requires further study. Identification and elucidation of EMT pathways could have a prognostic and therapeutic value. Targeting the EMT pathway or reversing it could be a potential strategy in suppressing cancer formation and metastasis. Specific markers could be developed that recognize a cancer-derived EMT mesenchymal cell. This can be vital in the development of new drugs that target metastatic mechanisms and help combat various diseases caused by the use of smokeless tobacco.

5. Conclusions

Tobacco consumption is one of the largest preventable causes of oral cancer. The present study found that STE induces cell death apoptosis in gingival epithelial cells in a mitochondrial potential-dependent manner. Furthermore, apoptosis-related and EMT-related markers are also increased in a concentration-dependent manner. The results demonstrate that tobacco plays a role in metabolic alterations of the periodontium.

Financial disclosures

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.04.068.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Alsanosy R.M. Smokeless tobacco (shammah) in Saudi Arabia: A review of its pattern of use, prevalence, and potential role in oral cancer. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6477–6483. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.16.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer M., Bull C.A., Daouk M.N., McArthur P.D., Lundmark G.J., Senoussi M. El. Shamma Usage and Oral Cancer in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 1985;5:135–140. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1985.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aravamudan B., Kiel A., Freeman M., Delmotte P., Thompson M., Vassallo R., Sieck G.C., Pabelick C.M., Prakash Y.S. Cigarette smoke-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in human airway smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014;306:840–854. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00155.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthana S., Labani S., Kailash U., Sinha D.N., Mehrotra R. Association of Smokeless Tobacco Use and Oral Cancer: A Systematic Global Review and Meta-Analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019;21:1162–1171. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awan, K.H., Patil, S., 2016. Association of smokeless tobacco with oral cancer - evidence from the South Asian studies: A systematic review. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pakistan 26, 775–780. https://doi.org/2434 [PubMed]

- Bagchi M., Balmoori J., Bagchi D., Ray S.D., Kuszynski C., Stohs S.J. Smokeless tobacco, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and antioxidants in human oral keratinocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00286-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettendorf O., Piffkò J., Bànkfalvi A. Prognostic and predictive factors in oral squamous cell cancer: Important tools for planning individual therapy? Oral Oncol. 2004;40:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat M.Y., Advani J., Rajagopalan P., Patel K., Nanjappa V., Solanki H.S., Patil A.H., Bhat F.A., Mathur P.P., Nair B., Prasad T.S.K., Califano J.A., Sidransky D., Gowda H., Chatterjee A. Cigarette smoke and chewing tobacco alter expression of different sets of miRNAs in oral keratinocytes. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25498-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccuzzi J. Smokeless tobacco. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2014;145:17–18. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8177(14)60258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffetta P., Hecht S., Gray N., Gupta P., Straif K. Smokeless tobacco and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:667–675. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffee B.W., Couch E.T., Ryder M.I. The tobacco-using periodontal patient: Role of the dental practitioner in tobacco cessation and periodontal disease management. Periodontol. 2016;2000(71):52–64. doi: 10.1111/prd.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, S.C., Vatanasapt, P., Yi-Hsin, Y., Zain, R.B., Kerr, A.R., Johnson, N.W., 2017. Oral cancer in South East Asia. Transl. Res. Oral Oncol. 2, 2057178X1770292. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057178x17702921

- Cory S., Adams J.M. The BCL2 family: Regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobe M., Sinha D.N., Rahman K. Smokeless tobacco use and its implications in WHO South East Asia Region. Indian J. Public Health. 2006;50:70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman J.L., Sammy M.J., Ballinger S.W. Mitochondrial toxicity of tobacco smoke and air pollution. Toxicology. 2017;391:18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Prasad G.L., Zacharias W. Combusted but not smokeless tobacco products cause DNA damage in oral cavity cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014;37:1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara H., Araya J., Ito S., Kobayashi K., Takasaka N., Yoshii Y., Wakui H., Kojima J., Shimizu K., Numata T., Kawaishi M., Kamiya N., Odaka M., Morikawa T., Kaneko Y., Nakayama K., Kuwano K. Mitochondrial fragmentation in cigarette smoke-induced bronchial epithelial cell senescence. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2013;305 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2020, 2020. , Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/26b007cd-en

- Hecht S.S. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:733–744. doi: 10.1038/nrc1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht S.S., Hoffmann D. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines, an important group of carcinogens in tobacco and tobacco smoke. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:875–884. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerboth S., Housman G., Leary M., Longacre M., Byler S., Lapinska K., Willbanks A., Sarkar S. EMT and tumor metastasis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2015;4 doi: 10.1186/s40169-015-0048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningfield J.E., Fant R.V., Tomar S.L. Smokeless tobacco: an addicting drug. Adv. Dent. Res. 1997;11:330–335. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D., Djordjevic M.V. Chemical composition and carcinogenicity of smokeless tobacco. Adv. Dent. Res. 1997;11:322–329. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann R.F., Zarrintan S., Brandenburg S.M., Kol A., de Bruin H.G., Jafari S., Dijk F., Kalicharan D., Kelders M., Gosker H.R., ten Hacken N.H.T., van der Want J.J., van Oosterhout A.J.M., Heijink I.H. Prolonged cigarette smoke exposure alters mitochondrial structure and function in airway epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. Tobacco Use and Oral Cancer: A Global Perspective. J. Dent. Educ. 2001;65:328–339. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2001.65.4.tb03403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreth F., Tuveson D.A. Twist induces an epithelial-mesenchymal transition to facilitate tumor metastasis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2004;3:1058–1059. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna Rao S., Mejia G., Roberts-Thomson K., Logan R. Epidemiology of Oral Cancer in Asia in the Past Decade- An Update (2000–2012) Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5567–5577. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.10.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallier T.E., Moylan J.T., Maturin E. Greater Sensitivity of Oral Fibroblasts to Smoked Versus Smokeless Tobacco. J. Periodontol. 2017;88:1356–1365. doi: 10.1902/jop.2017.170232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhou X., Wang Y. Smokeless tobacco extract inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in oral mucous fibroblasts. Oncol. Lett. 2018;16:5066–5074. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai H., May W.S., Gao F., Jin Z., Deng X. A Functional Role for Nicotine in Bcl2 Phosphorylation and Suppression of Apoptosis *. 2003;278:1886–1891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangipudy R.S., Vishwanatha J.K. Role of nitric oxide in the induction of apoptosis by smokeless tobacco extract. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1999;200:51–57. doi: 10.1023/A:1006985700851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjappa V., Renuse S., Sathe G.J., Raja R., Syed N., Radhakrishnan A., Subbannayya T., Patil A., Marimuthu A., Sahasrabuddhe N.A., Guerrero-Preston R., Somani B.L., Nair B., Kundu G.C., Prasad T.K., Califano J.A., Gowda H., Sidransky D., Pandey A., Chatterjee A. Chronic exposure to chewing tobacco selects for overexpression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase in normal oral keratinocytes. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015;16:1593–1603. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1078022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen P.T., Kudo Y., Yoshida M., Kamata N., Ogawa I., Takata T. N-cadherin expression is involved in malignant behavior of head and neck cancer in relation to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Histol. Histopathol. 2011;26:147–156. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Printz C. Users of smokeless tobacco had higher levels of exposure to nicotine, carcinogens than cigarette smokers. Cancer. 2016;122:987. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson P.B., Walsh M., Greene J., Ernster V., Grady D., Hauck W. Periodontal Effects Associated With the Use of Smokeless Tobacco. J. Periodontol. 1990;61:438–443. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.7.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz D.A., Meyer R.E., Tanzer J.M., Mirvish S.S., Lewin F. Public health implications of smokeless tobacco use as a harm reduction strategy. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96:1934–1939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva D., Cáceres M., Arancibia R., Martínez C., Martínez J., Smith P.C. Effects of cigarette smoke and nicotine on cell viability, migration and myofibroblastic differentiation. J. Periodontal Res. 2012;47:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha D.N., Rizwan S.A., Aryal K.K., Karki K.B., Zaman M.M., Gupta P.C. Trends of smokeless tobacco use among adults (aged 15–49 Years) in Bangladesh, India and Nepal. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2015;16:6561–6568. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.15.6561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivandzade F., Bhalerao A., Cucullo L. Analysis of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Using the Cationic JC-1 Dye as a Sensitive Fluorescent Probe. Bio-Protocol. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.21769/bioprotoc.3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov I., Hecht S.S., Ramakrishnan S., Gupta P.C. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines in smokeless tobacco products marketed in India. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;116:16–19. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliankatchi R.A., Sinha D.N., Rath R., Aryal K.K., Zaman M.M., Gupta P.C., Karki K.B., Venugopal D. Smokeless Tobacco Use is “Replacing” the Smoking Epidemic in the South-East Asia Region. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019;21:95–100. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed U.F., Bari A., Husain L. Leaching of 210Po in human saliva from smokeless tobacco. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2009;281:541–546. doi: 10.1007/s10967-009-0038-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toshiyuki M., Reed J.C. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell. 1995;80:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voulgari A., Pintzas A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer metastasis: Mechanisms, markers and strategies to overcome drug resistance in the clinic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer. 2009;1796:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh P., Epstein J. The Oral Effects of Chewing Tobacco. J. Ala. Dent. Assoc. 1996;80:40–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnakulasuriya K.A.A.S., Ralhan R. Clinical, pathological, cellular and molecular lesions caused by oral smokeless tobacco - A review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2007;36:63–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnakulasuriya S. Living with oral cancer: Epidemiology with particular reference to prevalence and life-style changes that influence survival. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:407–410. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnakulasuriya S. Smokeless tobacco and oral cancer. Oral Dis. 2004;10:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1354-523X.2003.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub J.A., Burt B.A. Periodontal effects and dental caries associated with smokeless tobacco use. Public Health Rep. 1987;102:30–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo S., Gao H., Henderson D., Zacharias W., Liu G., Tran Q., Prasad G.L. AKR1C1 as a Biomarker for Differentiating the Biological Effects of Combustible from Non-Combustible Tobacco Products. Genes (Basel). 2017;8:132. doi: 10.3390/genes8050132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Z., Yamaguchi A., Sakamoto K. Aberrant expression and altered cellular localization of desmosomal and hemidesmosomal proteins are associated with aggressive clinicopathological features of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1594-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Weinberg R.A. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer: complexity and opportunities. Front. Med. 2018;12:361–373. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0656-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.