Significance

The germinal center (GC) reaction generates high-affinity antibody–producing plasma cells and memory B cells that are pivotal for immune responses against pathogens and effective vaccination. However, it remains a challenging task to enhance GC reactions because increased antigen doses or repeated immunization, which should activate more B and T cells for GC formation, do not significantly augment antibody affinity. Here, we show that predetermined GC niches set the ceiling of GC numbers and thus limit GC responses. Clearance of the GC niche occupied by preexisting GC B cells may be a strategy to improve vaccine effectiveness or restore repressed antibody responses in autoimmune patients.

Keywords: GC niches, GC response, vaccination

Abstract

Antibody affinity maturation occurs in the germinal center (GC), a highly dynamic structure that arises upon antigen stimulation and recedes after infection is resolved. While the magnitude of the GC reaction is highly fluctuating and depends on antigens or pathological conditions, it is unclear whether GCs are assembled ad hoc in different locations or in preexisting niches within B cell follicles. We show that follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), the essential cellular components of the GC architecture, form a predetermined number of clusters. The total number of FDC clusters is the same on several different genetic backgrounds and is not altered by immunization or inflammatory conditions. In unimmunized and germ-free mice, a few FDC clusters contain GC B cells; in contrast, immunization or autoimmune milieu significantly increases the frequency of FDC clusters occupied by GC B cells. Excessive occupancy of GC niches by GC B cells after repeated immunizations or in autoimmune conditions suppresses subsequent antibody responses to new antigens. These data indicate that the magnitude of the GC reaction is restricted by a fixed number of permissive GC niches containing preassembled FDC clusters. This finding may help in the future design of vaccination strategies and in the modulation of antibody-mediated autoimmunity.

The production of neutralizing antibodies following vaccination or viral infections is the linchpin of protective immunity against subsequent infections. In the past, much effort has been invested in understanding the mechanism and developing vaccination strategies to produce high titers of neutralizing antibodies. The production of high-affinity antibodies depends on the germinal center (GC) reaction during which antigen-specific B cells collaborate with T cells, undergo Ig somatic hypermutation (SHM), and generate high-affinity antibody–producing plasma cells (PCs) and memory B cells (1–3). It remains enigmatic why increased numbers of antigen-specific B and T cells or dose of antigen do not proportionally increase GC output (4–6). In this regard, it is important to elucidate whether mechanisms exist that are responsible for restricting the overall magnitude of the GC reaction.

It is not yet clear whether there is a limit to the total number of GCs in peripheral lymphoid organs and whether GCs can develop in any location in B cell follicles. B cells commit to the GC cell fate not in the GC itself but at the interface of T/B cell regions (7–9). After antigen stimulation, responding B cells move to the border of the follicle and interact with local cognate T cells (9–11). This T/B cell interaction results in rapid proliferation of B cells in the outer follicular areas, where a fraction of activated B and T cells up-regulate Bcl6 and become the precursors of GC B cells and T follicular helper (Tfh) cells (7, 8). These outer follicular proliferation foci exhibit several GC-like features, such as expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase, which is required for both Ig SHM and class switch recombination (CSR) (12–14). In the case of Salmonella infection, SHM indeed occurs in these outer follicular foci (15). However, in most cases of antigen stimulation, GC-committed B and T cells migrate into B cell follicles to form mature GCs (16–18), suggesting that permissive GC niches within the follicles are needed to support the full maturation of GCs. A mature GC is segregated into a dark zone composed of proliferating B cells that undergo SHM and a light zone containing follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and Tfh cells that select high-affinity B cells for survival and clonal expansion (19–23). FDCs are specialized stromal cells that form sporadic clusters, and the integrity of FDC clusters is essential for the maintenance of GC reactions (24, 25). Immunization or inflammation activates the signaling pathway of Toll-like receptors in FDCs to promote GC B cell survival (26, 27). Immunization may also increase the number of FDCs, as one study has shown that marginal reticular cells, a specialized subset of stromal cells residing beneath the subcapsular sinuses in lymph nodes, proliferate and differentiate into FDCs after immunization (28). However, it is not yet clear whether FDCs form clusters at various sites inside B cell follicles during immune responses or represent preset elements of GC niches. While a flexible number of GC niches adapted to different immune responses could satisfy unlimited expansion of GC B cells, a fixed number of GC niches would force GC B cells into interclonal competition to select for the “best fit” clones of antibody-producing cells. Currently, we know little about the nature and capacity of the GC niche.

Here, we report that the mouse spleen contains a fixed number of FDC clusters that designate GC niches. These FDC clusters are preexisting and not changed in numbers by the immunization status, suggesting that they are associated with the stromal architecture at fixed locations. They are mostly empty in the absence of immunization and can become fully occupied by GC B cells depending on the immunization schemes or in an autoimmune milieu. Increased occupancy of FDC clusters by GC B cells inhibits subsequent GC responses, and clearance of preexisting GC B cells restores GC responses to new antigens. These findings indicate that the ultimate magnitude of a GC reaction is restricted by the available GC niches.

Results

The Spleen Contains a Fixed Number of FDC Clusters.

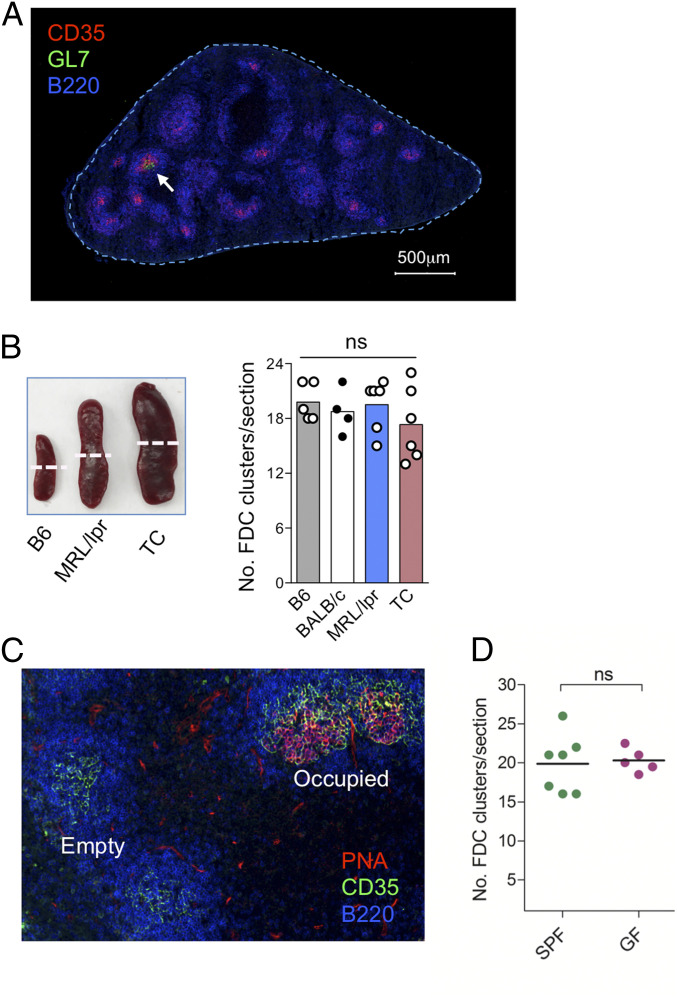

The access of only a fraction of antigen-activated B and T cells to GCs suggests that the niche capacity for GC reactions is limited. Since FDCs are essential components of the GC architecture, we decided to probe the nature of GC niche and its capacity by examining FDC networks. We first examined FDC networks in unimmunized mice by immunofluorescence staining using CD35 as a marker of the cells (29). The numbers of FDC clusters were scored on three to five serial cross-sections 70 μm apart along the midplane of the spleen (Fig. 1 A and B). To scrutinize sampling variations at different splenic planes, we also counted FDC clusters on cross-sections at one-half the distance between the midplane and terminus of the spleen and found that there were an equivalent number of FDC clusters to that at the midplane (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Therefore, sampling cross-sections around the midplane of the spleen does not yield significant variations in the number of FDC clusters. Through evaluation of serial sections from a total of 36 mice, we found that two forms of FDC clusters coexist in mice without intentional immunization: empty FDC clusters that do not contain GC B cells and occupied FDC clusters that are populated by GC B cells (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We found that unimmunized mice on different genetic backgrounds, such as C57BL/6 (B6) and Balb/c mice, had on average 20 ± 3 total FDC clusters/section (Fig. 1B), only a few of which were occupied by GC B cells (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). It is known that mice on a lupus-prone genetic background, such as MRL/MpJ-Faslpr (MRL/lpr) and triple-congenic B6.Sle1.2.3 (TC) mice, spontaneously develop splenomegaly and autoreactive GC reactions. In addition, commensal microbial stimulation may also change the immune status of the mice. To examine whether these immune environmental factors influence the number of FDC clusters, we enumerated FDC clusters in the spleen of germ-free (GF) and specific pathogen–free (SPF) B6 mice as well as in the enlarged spleen of MRL/lpr and TC mice. Total numbers of FDC clusters in spleens of MRL/lpr, TC, or GF mice were equivalent to those in SPF B6 mice (Fig. 1 B and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D). Together, these findings show that the mouse spleen has a fixed number of FDC clusters that are preassembled in the absence of intentional immunization, and this number remains constant irrespective of the acquired microbiota or the presence or absence of chronic inflammation.

Fig. 1.

The total number of splenic FDC clusters is predetermined. (A) An image of an entire cross-section at the midplane of the spleen from unimmunized B6 mice shows 17 FDC clusters with 1 occupied by GL7+ GC B cells (white arrow). (B) Left shows spleens from B6, MRL/lpr, or TC mice, with white dash lines depicting the midplane at which immunofluorescence images of the cross-sections were taken. Right shows numbers of FDC clusters per cross-section. (C) A representative immunofluorescence image shows empty and occupied FDC clusters. (D) Numbers of FDC clusters per cross-section of spleens from B6 mice under SPF and GF conditions. Each dot represents data from an individual mouse, and bars or lines indicate the mean values. ns, not significant.

Immunization Does Not Cause New FDC Cluster Formation but Leads GC B Cells to Fill Preexisting FDC Clusters.

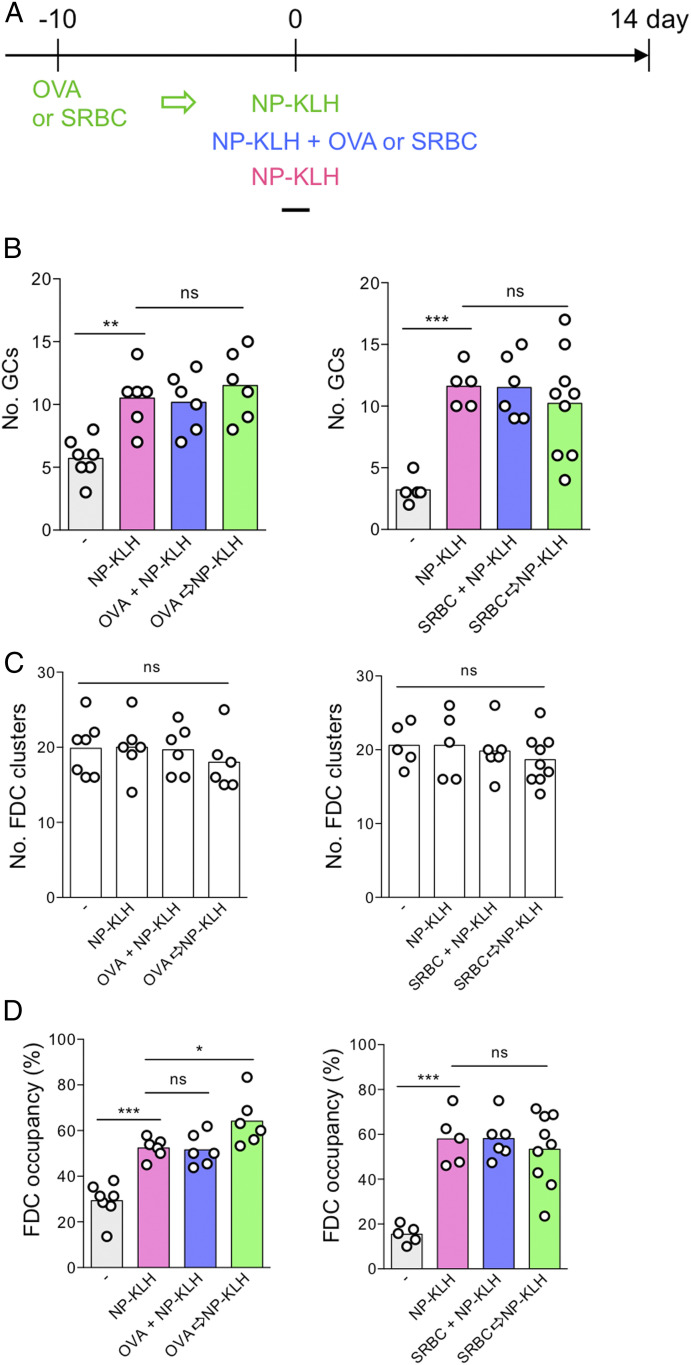

GCs are temporal structures formed around FDC clusters by antigen-activated B and T cells. If the preset FDC clusters delineate the GC niches to be filled by GC B and T cells after immunization, it follows that immunization should increase the FDC occupancy by GC B cells but not the total number of FDC clusters. To test this hypothesis, we employed different immunization schemes to determine whether the number of empty and occupied FDC clusters was changed by different schemes of immunization (Fig. 2A). We found that immunization with a single dose of the T-dependent antigen 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP) conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (NP-KLH) doubled the numbers of GC B cell–occupied FDC clusters in 14 d compared to those in unimmunized mice (Fig. 2B); however, the total number of FDC clusters remained the same as in unimmunized mice (Fig. 2C). Simultaneous or sequential injection of NP-KLH and ovalbumin (OVA), which should activate more B and T cells than NP-KLH or OVA alone, did not increase the number of occupied or total FDC clusters in comparison to NP-KLH immunization alone. Similar results were found when mice were immunized with NP-KLH together or sequentially with the particulate antigen sheep red blood cells (SRBC) (Fig. 2 B–D). The proportion of occupied FDC clusters goes up to 60% of the total FDC clusters in mice after immunization (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

The total number of splenic FDC clusters remains unchanged with an increased occupancy by GC B cells after immunization. (A) Timeline of immunization. The total number of (B) GCs, (C) FDC clusters, and (D) the percentage of FDC clusters occupied by GC B cells per cross-section of spleens of unimmunized mice (−) or mice immunized with NP-KLH alone (NP-KLH), simultaneously with OVA or SRBC (OVA+NP-KLH or SRBC+NP-KLH), or following OVA or SRBC priming (OVA→NP-KLH or SRBC→NP-KLH). Symbols represent data from each mouse and bars indicate the mean values. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

It is generally believed that cognate Tfh cells are the limiting factor for which GC B cells compete in order to survive and undergo clonal expansion (21, 23, 30). Since increasing doses and complexity of antigens cannot further boost the number of FDC clusters, we tested whether it is constrained by a limited Tfh cell pool. We transferred OVA-specific OT-II CD4+ T cells into wild-type (WT) mice, immunized the recipient mice with NP-OVA, and then analyzed NP-specific antibody production and FDC clusters (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The increased number of OVA-specific CXCR5+ Tfh cells moderately enhanced the production of NP-specific IgG titers at day 7, presumably due to increased extrafollicular OVA-specific T/B cell interaction that promotes generation of short lived class-switched PCs at this stage; however, there was no difference in NP-IgG antibody titers between WT and OT-II T cell recipient mice by day 14 after immunization (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). Elevated numbers of antigen-specific CXCR5+ Tfh cells did not increase the number of NP-specific GC B cells or occupied FDC clusters (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E).

Thus, we conclude from the above experiments that immunization only leads to an increase in the occupancy of preexisting FDC clusters by GC B cells but not the formation of de novo FDC clusters. In addition, while immunization increases the number and the size of GCs, the total number of GCs does not surpass the preexisting number of FDC clusters even at high antigen doses, repeated or complex antigen immunization, or with increased numbers of antigen-specific Tfh cells.

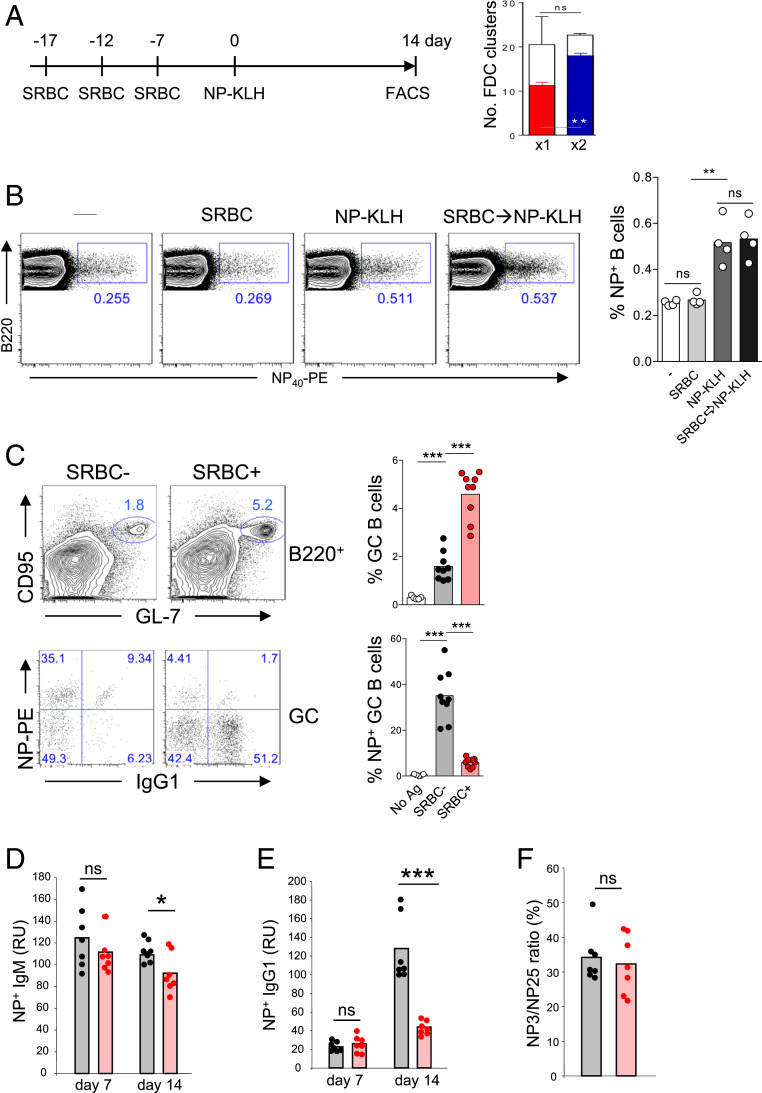

A Limited Number of FDC Clusters Restricts GC Responses.

Our observation that GC B cells only colonize predetermined FDC clusters suggests that GC responses may be restricted by the available number of FDC niches. To determine whether FDC occupancy by GC B cells from prior immunization interferes with subsequent GC responses to a second antigen, we developed an immunization scheme by repeatedly immunizing B6 mice with SRBC so that more than 80% of FDC clusters were occupied by GC B cells (Fig. 3A). We then immunized these mice with NP-KLH and examined whether NP-specific GC reactions and anti-NP antibody responses were affected when FDC clusters were filled with SRBC-reactive GC B cells. NP-KLH immunization induced an equal expansion of NP-specific B cells in mice with or without SRBC priming, demonstrating that repeated SRBC immunizations did not affect total B cell responsiveness to the second antigen NP-KLH (Fig. 3B). However, unlike SRBC-unprimed mice, in which nearly 40% of GC B cells bound NP, SRBC-primed mice generated ∼3× more total GC B cells relative to unprimed mice, and only about 5% of them bound NP, showing a threefold reduction in NP-specific GC B cells compared to SRBC-unprimed mice (Fig. 3C). To evaluate the impact of SRBC priming on subsequent antibody responses to NP-KLH, we measured serum levels of anti-NP antibodies in mice with or without SRBC priming at days 7 and 14 after NP-KLH immunization. Antibodies in the first week after immunization are largely produced by extrafollicularly differentiated PCs independent of GC reactions, since GCs start to form at day 4 and grow to the maximal size at day 10 to 14 after immunization. We found that at day 7 after NP-KLH immunization, mice with or without SRBC priming produced an equivalent amount of NP-specific IgM and IgG1 antibodies (Fig. 3 D and E). Thus, saturating FDC clusters with SRBC-specific GC B cells did not impede early antibody response to the subsequent NP-KLH antigen. As the NP-specific response proceeded to day 14, B cells that had undergone CSR and clonal expansion in GCs contributed to elevated titers of NP-specific IgG1 in SRBC-unprimed mice. However, such a robust increase in NP-specific IgG1 was nearly absent in SRBC-primed mice (Fig. 3E), showing that production of GC-dependent antibodies to subsequent antigenic challenge was impaired when GC niches were filled with preexisting GC B cells. Despite fewer NP-specific GC B cells and lower titers of NP-specific IgG1 generated in SRBC-primed mice, affinity maturation of NP-specific IgG1 antibodies was not affected by the prior SRBC immunization, as evidenced by a similar ratio of anti-NP3 versus anti-NP25 serum IgG1 titers in SRBC-primed and -unprimed mice (Fig. 3F). Based on these results, we propose that excessive occupancy of FDC clusters by GC B cells of prior immunization reduces the permissive GC niche space for the subsequent GC reactions to new antigens. However, those B cells specific for the new antigen can still undergo affinity maturation once they enter GC niches.

Fig. 3.

Excessive FDC occupancy impairs subsequent GC responses to new antigens. (A) Immunization scheme (Left) and FDC occupancy by SRBC immunization (Right). (Right) Total numbers of empty FDC clusters (open bars) and occupied FDC clusters (filled bars) per cross-section from spleens of mice immunized with a single dose (×1) or two doses of SRBC (×2), respectively (n = 3). (B) Flow cytometric analyses of splenic B cells in unimmunized mice (−), mice immunized with a single dose of SRBC (SRBC) or NP-KLH (NP-KLH), as well as with NP-KLH following three doses of SRBC immunization (SRBC→NP-KLH). Shown are the FACS analysis (Left) and statistics (Right) of NP-binding B cells. (C) Contour plots show B cells from mice with (SRBC+) or without (SRBC−) SRBC priming stained with anti-CD95 and GL7. Dot plots display NP-binding B cells within the gated GC B cell (CD95+ GL7+) population. (D and E) Serum titers of anti-NP antibodies. Mice were primed with three doses of SRBC (red dots) or without preimmunization (black dots). NP-specific IgM (D) and IgG1 (E) were measured on days 7 and 14 after NP-KLH immunization, respectively. (F) The ratio of high-affinity (NP3-binding) to total (NP25-binding) NP-specific IgG1 was determined on day 14. Numbers in the FACS plots indicate the percentages of B cells in the outlined areas. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Bars indicate the mean values. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

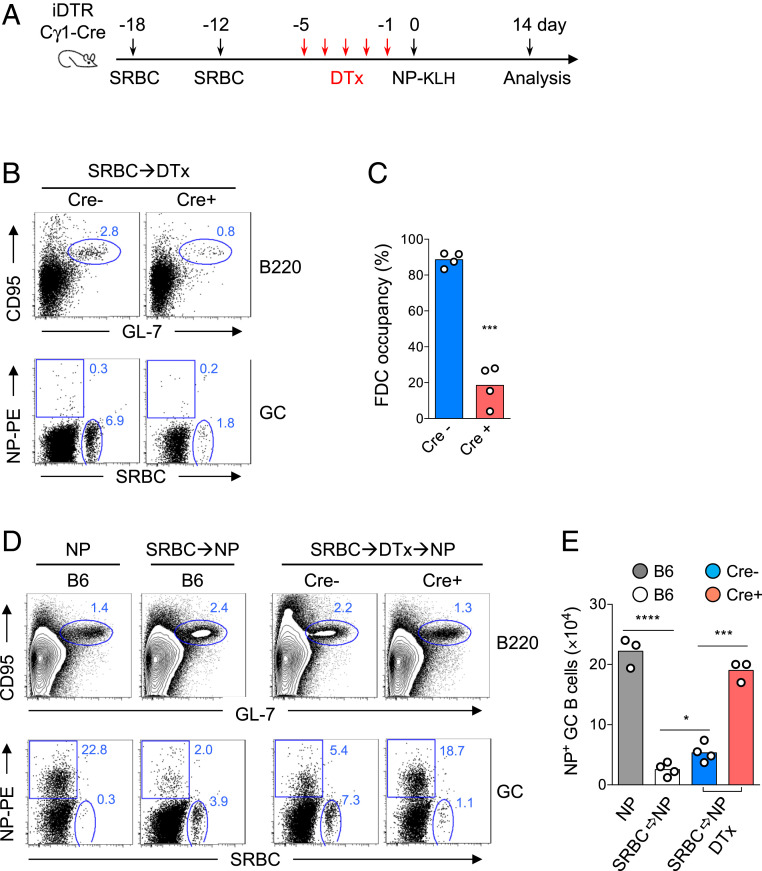

Clearance of the GC B Cell–Occupied FDC Niches Restores Optimal GC Reactions to the Subsequent Antigen Immunization.

Our above experiments suggest that low GC responses to the second antigen may be caused by the existing GC B cells from the prior immunization that occupy FDC clusters, thus imposing a spatial impediment that limits the recruitment of newly activated B cells into the GC niche. To determine whether this is the case, we decided to use Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice to inducibly deplete existing GC B cells from prior immunization and then examine whether this could restore the subsequent GC response to a new antigen. In Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice, inducible diphtheria toxin receptor (iDTR) is expressed in GC B cells after Cγ1-Cre–mediated excision of a floxed STOP cassette (31, 32). GC B cells can then be conditionally depleted following diphtheria toxin (DTx) injection. We repeatedly immunized Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice with SRBC to saturate FDC clusters with GC B cells (Fig. 4 A and C). At 7 d after the last SRBC injection, we gave mice five doses of DTx and assessed the efficiency of GC B cell depletion by examining total and SRBC-specific GC B cells by flow cytometry and FDC occupancy by immunohistology. Compared with iDTR control mice without the Cγ1-Cre allele, DTx treatment resulted in a ∼70% decrease in total GC B cells and SRBC-specific GC B cells (Fig. 4B), as well as a reduced number of occupied FDC clusters by GC B cells in Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice (Fig. 4C), indicating that the treatment had freed more GC niche space. To examine whether these cleared FDC clusters could support subsequent GC reactions to a new antigen, we immunized SRBC-primed Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice and iDTR controls with NP-KLH after DTx treatment (Fig. 4A). At 14 d after NP-KLH immunization, we analyzed antigen-specific GC reactions by flow cytometry. Antigen specificity of GC B cells was confirmed because NP-binding GC B cells were barely detectable in mice immunized with SRBC (Fig. 4B), and likewise, SRBC-binding GC B cells were almost absent in mice immunized with NP-KLH (Fig. 4 D, Lower Left). We found that SRBC priming decreased the number of NP-specific GC B cells in B6 mice as well as in iDTR control mice with DTx treatment. In contrast, NP-specific GC B cells in Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice with DTx-mediated SRBC-GC B cell depletion were restored to a similar number as in NP-KLH–immunized B6 mice without SRBC priming (Fig. 4 D and E).

Fig. 4.

Release of FDC occupancy by depleting GC B cells of the previous immune response rescues GC reactions to a new antigen. (A) Timeline of immunization and GC B cell depletion. (B) Efficiency of GC B cell depletion. Splenic B cells, from Cre- or Cγ1-Cre+ iDTR mice treated with DTx following SRBC immunization, were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 0 as indicated in A. Shown in the Top dot plots are percentages of total GC B cells and in the Bottom, NP- and SRBC-binding GC B cells (n = 4). (C) The spleens used in B were cut at the midplane. Percentages of occupied splenic FDC clusters on cross-sections in mice of the indicated groups are shown. (D) Flow cytometry analyses of splenic B cells from B6 mice immunized with NP-KLH with (SRBC→NP) or without (NP) SRBC priming, as well as B cells from Cre- or Cγ1-Cre+ iDTR mice on day 14 after NP-KLH immunization following SRBC priming and DTx treatment (SRBC→DTx→NP). Top contour plots show percentages of total GC B cells, and Bottom dot plots show proportions of NP- and SRBC-binding B cells within the GC population. (E) The absolute numbers of NP-binding GC B cells in mice of the indicated groups. Numbers in the FACS plots indicate percent B cells in the outlined areas. Each dot represents an individual mouse. Bars indicate the mean values. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

GC reactions can vary substantially depending on the immunizing antigens, such as particulate, soluble antigens, or living virus (33, 34). In addition, the usage of adjuvants may elicit innate immune signals and enhance antigen retention, thus affecting the GC niche architecture and antigen deposition (35). We next examined whether FDC occupancy after protein antigen priming in the presence of alum adjuvant could also interfere with subsequent GC reactions to a new antigen. B6 mice possessed a comparable number of total GC B cells after NP-OVA immunization with or without prior priming with KLH in alum adjuvant (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A); however, KLH-primed mice exhibited strong inhibition to the subsequent NP-OVA immunization, as they had only 4% NP-binding GC B cells compared to KLH-unprimed mice that possessed more than 30% of NP-specific GC B cells and a nearly sevenfold reduction of NP-specific GC cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and C). Depletion of GC B cells in KLH-primed mice using DTx markedly restored the number of GC B cells to the new antigen NP-OVA from 6 to more than 40% (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C). Thus, GC B cells elicited by prior immunization with protein antigen in alum adjuvant negatively impact a subsequent GC reaction to an unrelated hapten–protein conjugate, similar to what we had observed in SRBC-primed mice.

Together, these data show that the ultimate magnitude of GC reactions is limited by the number of available GC niches. Since the removal of preexisting GC B cells is sufficient to restore the capacity of GC niches to accommodate a new GC reaction, we propose that the spatial saturation of the niche by prior GC B cells rather than the limit on FDC’s capacity for antigen deposition is the critical factor that influences the subsequent immunization.

Excessive FDC Occupancy in Autoimmune Mice Impairs Subsequent T-dependent Antibody Responses.

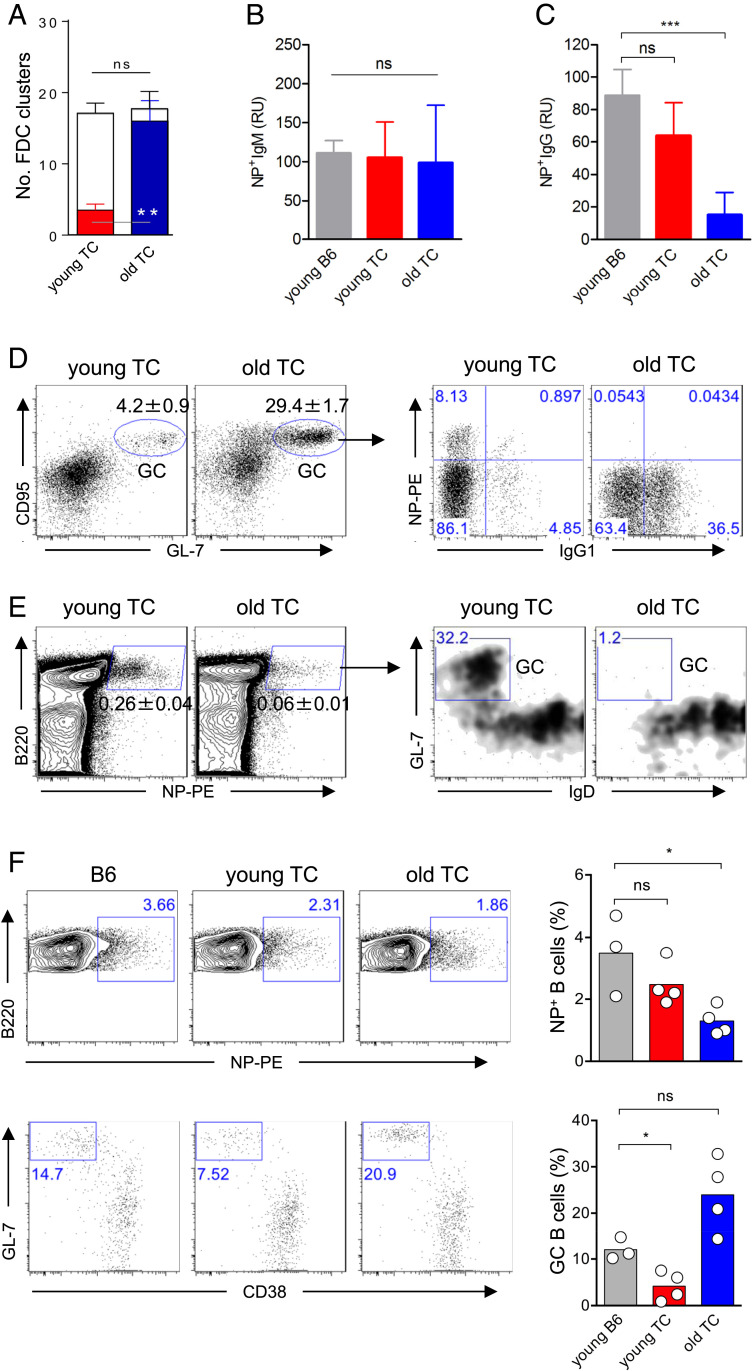

Our finding of limited numbers of FDC clusters has an important biological implication, namely that excessive ongoing GC responses could diminish the efficacy of intentional immunizations such as vaccinations. FDC networks have been shown to be essential for aberrant GC reactions in autoimmune animal models (36). Mice and humans with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) develop spontaneous GCs that contribute to the production of pathogenic autoantibodies (37). For instance, TC female mice generate spontaneous GCs and autoantibodies against double-stranded DNA and chromatin at 4 mo of age. By 10 mo of age, ∼98% of TC females develop splenomegaly and fatal glomerulonephritis (38, 39). We examined FDC occupancy in preautoimmune young (2-mo-old) and old TC mice that had developed glomerulonephritis (10-mo-old). While both young and old TC mice possessed the same number of FDC clusters as B6 control mice, they exhibited a marked difference in the number of occupied FDC clusters; the young TC mice had ∼20% of FDC clusters occupied by GC B cells, whereas in old TC mice, 90% of FDC clusters were occupied (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

FDC cluster occupancy by spontaneous GC B cells in lupus mice compromises GC reactions to immunization. (A) Cross-sections of spleens from young (8 to 10 wk) and old (10 mo) TC mice were stained for PNA, B220, and CD35. Numbers of empty FDC clusters (open bars) and FDC clusters filled with spontaneous GC B cells (closed bar) are shown with mean ± SD (n = 4). (B and C) Age-matched B6 and young TC mice as well as old TC mice were immunized with NP-KLH in alum. Serum levels of NP-specific IgM (B) and IgG (C) were determined 14 d later. Relative units (RU) are shown as mean with SD. Data were from four B6 mice, five young, and seven old TC mice. (D) Dot plots show splenic GC B cells from five young and seven old TC mice 14 d after NP-KLH immunization. Gated GC B cells are further displayed by NP-PE and IgG1 staining. (E) Percentages of GC B cells among the NP+ B cell population of young (n = 5) and old TC mice (n = 7). (F) Dot plots show percentages of GC B cells of the gated NP+ B220+ population in the spleen of Rag-1−/− mice received lymphocytes from B6, young, or old TC mice. Bars depict mean values. Each dot represents an individual mouse. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

To determine whether excessive FDC occupancy by autoreactive GC B cells affected humoral responses against new exogenous antigens, we immunized both young and old TC mice with NP-KLH and measured NP-specific GC reactions and antibody production. Compared with control B6 mice, both young and old TC mice produced normal levels of NP-specific IgM, indicating that NP-specific B cells are normally activated and differentiate into IgM-producing PCs in TC mice regardless of the autoimmune status (Fig. 5B). In contrast, old TC mice produced markedly lower titers of anti-NP IgG than did young TC and B6 control mice (Fig. 5C). Flow cytometric analysis revealed that, compared to young TC mice, old TC mice possessed a significantly larger population of total GC B cells that contained a negligible number of NP-specific GC B cells (Fig. 5D). Similarly, when the total splenic B cell population was examined, NP-KLH–immunized old TC mice contained a significantly lower proportion of NP-binding B cells compared with young TC mice, and almost none of these cells were GC B cells (Fig. 5E).

To exclude the possibility that the impaired antibody response to a new antigen in old TC mice was caused by defective T or B cell function, we adoptively transplanted purified splenic T and B cells from old TC mice into Rag-1−/− mice. Rag-1−/− mice, having received the same numbers of donor T and B cells from WT B6 or young TC mice, were used as controls. At 2 mo after lymphocyte engraftment, Rag-1−/− hosts were immunized with NP-KLH, and NP-specific GC responses were examined by flow cytometry. We found that after immunization, there were slightly reduced numbers of NP-specific B cells in Rag-1−/− mice receiving lymphocytes from old TC mice relative to those that had received lymphocytes from young TC or B6 donors. However, Rag-1−/− mice with lymphocytes from old TC mice mounted robust GC reactions, as evidenced by an equivalent frequency of NP-specific GC B cells in the hosts receiving young TC or B6 lymphocytes (Fig. 5F). These data show that defective GC responses to a newly encountered antigen in old TC mice is unlikely a result of impaired T and B cell function. Rather, they suggest that the excessive occupancy of FDC clusters by the autoreactive GC B cells is a major factor that attenuates GC responses to the new immunogen.

Discussion

Since the discovery that development of high-affinity antibody–producing PCs and memory B cells occurs in GCs, most efforts have been focused on the major players GC B cells and Tfh cells. Recent studies on lymphoid stroma have led to a growing appreciation of preexisting local stromal cells that are essential for de novo GC formation (40, 41). A fundamental question is whether these stromal cells assemble GC niches that are predetermined or flexible in numbers and location in peripheral lymphoid organs. In this study, we addressed this question by evaluating the number of clusters formed by FDCs, the stromal cells that demarcate the light zone of GCs. Through quantification of FDC clusters on serial cross-sections of the spleen from mice that are either germ free, immunized with different antigens, or in autoimmune condition, we found all spleen cross-sections to contain ∼20 FDC clusters. This number is invariable on serial cross-sections from more than 100 mice representing different immune statuses, thus validating our conclusion that GC niches are preformed in a fixed number in the spleen. We also attempted to quantify FDC clusters in mesenteric or inguinal lymph nodes in unimmunized and once or repeatedly immunized B6 mice. However, it is hard to align an identical section plane of lymph nodes, and we found hugely variable numbers of FDC clusters among mice under these different immunization conditions. Future studies with light sheet microscopy will help determine the absolute number of GC niches in spleen and lymph nodes and may also reveal the predetermined histological sites at which GC niches are formed.

GCs have been shown to be open structures that can be seeded by newly activated B cells; and adjuvants and the presence of cognate Tfh cells promote recruitment of GC B cell precursors to preexisting GCs (42). Although an open GC structure seems capacious to hold many B cells responding to unrelated antigens, its actual capacity to support consecutive immunizations has not been determined. There is a rich body of old literature describing the phenomenon of “antigenic competition,” such as the immune response to horse red blood cells suppressing the ensuing response to non–cross-reactive SRBCs (43, 44). Our proposition that a fixed number of GC niches provide a limited capacity for GC reactions may relate to these old observations. We determined FDC occupancy in naïve mice and found that ∼80% of FDC clusters were devoid of GC B cells. While missing GC B cells on an individual plane of the FDC cluster may overrate the frequency of “empty” FDC clusters, our results nevertheless show that 80% of FDC clusters are not completely filled by GC B cells. Indeed, immunization markedly increases FDC occupancy by GC B cells. The frequency of GC B cell–occupied FDC clusters does not linearly correlate with antigen dose, as immunization with one antigen or simultaneously two different antigens still leaves around 35% FDC clusters unoccupied by GC B cells. Repeated immunization could fill FDC occupancy up to 85%. In autoimmune mice, FDC occupancy further increases to more than 90%, with 40% of spleens exhibiting 100% FDC occupancy by GC B cells. Thus, while FDC clusters can be saturated by continuously generated GC B cells over time, the total number of GC niches is not altered by the immune status in the mice. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that when mice with >80% FDC clusters occupied by preexisting GC B cells were immunized with a new antigen, they generated much less GC B cells responding to that antigen. Interestingly, the few incoming GC B cells have the chance to win interclonal competition against preexisting GC B cells and achieve affinity maturation. Therefore, our results show that limited GC niches constitute a spatial constraint that restricts the magnitude of GC responses. In support of this notion, we have shown that freeing GC niche space by depleting preexisting GC B cells can restore GC reactions to an incoming immunogen.

It is plausible to think that filling of empty GC niches might occur in order, depending on their locations and accessibility to antigens and GC precursors. However, we did not observe a discernible pattern of spatial distribution of empty and filled FDC clusters in the spleen of mice upon single or serial immunization. At present, we do not know whether all GC niches behave similarly in accepting newly committed GC precursors. It is also unclear whether GC B cells to a new antigen are prone to enter remaining empty niches or to share occupied niches with preexisting GC B cells. In theory, any niche should have a volume boundary, and the GC niche is of no exception; however, the limited capacity of GC niches to accommodate only two to three consecutive immunizations is unexpected. While B and T cells are the key players in GC reactions, our data indicate that the GC niche capacity should also be taken into account for designing successful vaccination strategies. Thus, it has been noticed that vaccination often fails to elicit effective humoral responses, especially in very young and very old individuals (45). While immature GC niches may cause unresponsiveness in neonates (46), GC niches in elderly individuals may be exhausted by accumulating GC B cells of past infections. Apart from the age dependence of GC responses to vaccines, we and others have observed that lupus mice do not respond well to immunization (47, 48). Several mechanisms may account for this immunological impairment, including defective APC function, reduced T cell responses, dysregulated Tregs, and biased repertoire of B and T cells toward autoantigens. In addition, a previous report shows that inflammation disrupts the layer of macrophages at subcapsular sinuses in lymph nodes, which leads to a poor B cell response to a new antigen that generates lower numbers of GC B cells and PCs producing antigen-specific IgM or IgG (49). We have observed that autoimmune TC mice have a lower IgG level while maintaining a normal IgM titer against a new antigen, indicating a distinct mechanism that suppresses GC responses in these mice. Our finding that GC niches were nearly saturated by autoreactive GC B cells provides an explanation for the impaired humoral immunity in lupus mice. Since our model reveals that the occupancy of GC niches may influence the outcome of subsequent immunization, it will be of great interest to determine whether autoimmune patients or elderly individuals have excessive FDC cluster occupancy due to ongoing immune responses. If this is the case, a better immunization strategy should be designed to elicit an effective vaccination in such individuals. Future studies are also needed to expand our understanding of GC niche formation and of GC niche–derived factors that may support the full maturation of GCs.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6J (B6), BALB/c, B6.NZMSle1/Sle2/Sle3 (TC), MRL/MpJ-Faslpr (MRL/lpr), Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai (iDTR), Rag1−/−, and Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn (OT-II) transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Cγ1-Cre mice, obtained from K.R. laboratory (32), were crossed to iDTR mice to generate Cγ1-Cre/iDTR mice. iDTR littermates without the Cγ1-Cre allele were used as controls. GF mice were housed at the New York University (NYU) animal facility, and the spleens were provided by Dan Littman's laboratory. All mice were maintained in a SPF facility at The Feinstein Institutes, and animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Feinstein Institutes.

Immunization.

For experiments shown in Figs. 2 to 4, 8- to 12-wk-old mice were used for immunization. For experiments shown in Fig. 5, young (8- to 10-wk old) and old (10-mo old) female TC mice received intraperitoneal (ip) injection of antigens. Primary immunization was carried out by injecting 80 μg each protein antigen precipitated in Imject Alum (ThermoScientific). All protein antigens OVA, KLH, NP-KLH, and NP-OVA were from Biosearch Technologies. Repeated immunization of SRBC was done by ip injection of 2 × 108 SRBC (Cocalico Biologicals), followed by two more ip injections of 109 SRBC. For depletion of GC B cells, iDTR Cγ1-Cre+ mice and iDTR Cre− control littermates received a daily dose of DTx (Sigma, 25 ng/g bodyweight, ip) for 5 consecutive d.

Adoptive Transfer.

Single-cell suspension was prepared from spleens of 2-mo-old B6 and TC mice or from 10-mo-old TC mice. Lymphocytes were purified by staining splenocytes with biotin-conjugated antibodies for CD11b, Gr1, and CD11c and immunomagnetically depleting biotin-labeled myeloid cells with a biotin selection kit (StemCell Tech). 107 lymphocytes from 2-mo-old TC and B6 mice or 10-mo-old TC mice were respectively transferred into Rag1−/− mice.

For adoptive T cell transfer, T cells were purified from OT-II mice using a mouse CD4 T cell enrichment kit (StemCell Tech). A total of 2 × 105 purified CD4+ T cells were transferred into B6.SJL mice.

Immunofluorescence Analysis.

Spleens were cut at the midplane and fixed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 3% paraformaldehyde for 45 min at 4 °C followed by dehydration in sucrose solution (30% [wt/vol] in PBS) for 1 to 2 h at 4 °C. Spleens were embedded in Tissue-Tek optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura) and frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath. Three to five serial 7-μm cross-sections were processed 70 μm apart using a cryostat (Leica). Sections were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 5 min. After rehydration with PBS, sections were blocked for 45 min at room temperature (RT) with 10% goat serum in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T). Sections were then stained with specific antibodies in PBS-T with in a humidified chamber at RT for 1 h. Antibodies used for visualizing B cell follicles and FDC clusters were anti-B220 (RA3-6B2, eBioscience) and anti-CD35 (8C12, BD Biosciences), respectively. GCs were stained by GL7 (GL7, BD Pharmingen) or PNA (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured with an LSM 880 confocal system (Zeiss) and analyzed with Zen imaging software (Zeiss).

Flow Cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], and 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]). Aliquotes of splenocytes were first incubated with Mouse BD Fc Block (BD Biosciences) for 10 min at RT to block antibody binding to Fc receptors and then stained for 15 min at 4 °C with antibodies specific to cell-surface markers. After washing with FACS buffer, cells were resuspended in FACS buffer containing DAPI for dead cell exclusion. Data were acquired on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, version 10.0).

Antibodies specific to the following cell-surface markers were used: B220 (RA3-6B2, eBioscience), CD19 (eBio1D3, eBioscience), CD95 (Jo2, BD Pharmingen), GL7 (GL7, BD Pharmingen), IgG1 (X56, BD Biosciences), IgD (11-26, eBioscience), CD38 (90, BD Biosciences), CXCR5 (2G8, BD Pharmingen), and CD45.2 (104, eBioscience). NP40-PE (Biosearch Technologies), KLH-AlexaFluor488, and carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled SRBC were used for detecting antigen specific B cells. KLH (Biosearch Technologies) was conjugated to the Alexa Fluor 488 dye with an Alexa Fluor 488 microscale protein labeling kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Detection of SRBC-binding B cells was performed as described (50) with modifications. Briefly, after washing three times with 15 mL PBS, 4 × 108 SRBC (Cocalico Biologicals) was resuspended in 1 mL PBS and labeled with 5 μM CFSE (Invitrogen) for 10 min at RT. CFSE-labeled SRBC was washed three times with 1 mL FACS buffer and resuspended in 1 mL FACS buffer. A total of 20 μL CFSE-labeled SRBC were then added to 80-μL aliquotes of surface-marker–labeled splenocytes and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C. After staining, cells were washed with FACS buffer, resuspended in DAPI-containing FACS buffer, and analyzed with an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Serum was collected from mice on day 7 and day 14 after immunization. ELISA for measuring NP-specific IgM and IgG as well as affinity maturation was performed as previously described (51).

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 6.0. P values were calculated from data of all independent replicates by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. Data are presented as means ± SD. P values of <0.05 were considered significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant.

Online Supplemental Material.

SI Appendix, Fig. S1 shows FDC clusters and GCs on the cross-sections of B6, GF, and MRL/lpr mice. SI Appendix, Fig. S2 shows GC reactions in the presence of increased numbers of Tfh cells. SI Appendix, Fig. S3 shows sequential GC reactions elicited by different protein antigens in the presence of alum and GC reactions to the second antigen with or without depletion of GC B cells to the primary antigen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Littman (NYU) for germ-free mice; all members of the Y.-R.Z. laboratory for suggestions; A. Davidson for helpful discussions; and D. Littman and A. Davidson for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by an Institution Fund (to Y.-R.Z.) and in part by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to H.G.). P.A. was a recipient of a fellowship from Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2100576118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.MacLennan I. C., Germinal centers. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12, 117–139 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesin L., Ersching J., Victora G. D., Germinal center B cell dynamics. Immunity 45, 471–482 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisel F., Shlomchik M., Memory B cells of mice and humans. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35, 255–284 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih T. A., Meffre E., Roederer M., Nussenzweig M. C., Role of BCR affinity in T cell dependent antibody responses in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 3, 570–575 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le T. V., Kim T. H., Chaplin D. D., Intraclonal competition inhibits the formation of high-affinity antibody-secreting cells. J. Immunol. 181, 6027–6037 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman Z., et al., T follicular helper cell dynamics in germinal centers. Science 341, 673–677 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffey F., Alabyev B., Manser T., Initial clonal expansion of germinal center B cells takes place at the perimeter of follicles. Immunity 30, 599–609 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerfoot S. M., et al., Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity 34, 947–960 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garside P., et al., Visualization of specific B and T lymphocyte interactions in the lymph node. Science 281, 96–99 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reif K., et al., Balanced responsiveness to chemoattractants from adjacent zones determines B-cell position. Nature 416, 94–99 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada T., et al., Antigen-engaged B cells undergo chemotaxis toward the T zone and form motile conjugates with helper T cells. PLoS Biol. 3, e150 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall J. L., et al., Early B blasts acquire a capacity for Ig class switch recombination that is lost as they become plasmablasts. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 3506–3512 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muramatsu M., et al., Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell 102, 553–563 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roco J. A., et al., Class-switch recombination occurs infrequently in germinal centers. Immunity 51, 337–350.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Niro R., et al., Salmonella infection drives promiscuous B cell activation followed by extrafollicular affinity maturation. Immunity 43, 120–131 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatto D., Paus D., Basten A., Mackay C. R., Brink R., Guidance of B cells by the orphan G protein-coupled receptor EBI2 shapes humoral immune responses. Immunity 31, 259–269 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira J. P., Kelly L. M., Xu Y., Cyster J. G., EBI2 mediates B cell segregation between the outer and centre follicle. Nature 460, 1122–1126 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green J. A., Cyster J. G., S1PR2 links germinal center confinement and growth regulation. Immunol. Rev. 247, 36–51 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen C. D., Okada T., Cyster J. G., Germinal-center organization and cellular dynamics. Immunity 27, 190–202 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Silva N. S., Klein U., Dynamics of B cells in germinal centres. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 137–148 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gitlin A. D., Shulman Z., Nussenzweig M. C., Clonal selection in the germinal centre by regulated proliferation and hypermutation. Nature 509, 637–640 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heesters B. A., Myers R. C., Carroll M. C., Follicular dendritic cells: Dynamic antigen libraries. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 495–504 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Victora G. D., et al., Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter. Cell 143, 592–605 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X., et al., Follicular dendritic cells help establish follicle identity and promote B cell retention in germinal centers. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2497–2510 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen C. D., Cyster J. G., Follicular dendritic cell networks of primary follicles and germinal centers: Phenotype and function. Semin. Immunol. 20, 14–25 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garin A., et al., Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by follicular dendritic cells is pivotal for germinal center onset and affinity maturation. Immunity 33, 84–95 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das A., et al., Follicular dendritic cell activation by TLR ligands promotes autoreactive B cell responses. Immunity 46, 106–119 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarjour M., et al., Fate mapping reveals origin and dynamics of lymph node follicular dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1109–1122 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roozendaal R., Carroll M. C., Complement receptors CD21 and CD35 in humoral immunity. Immunol. Rev. 219, 157–166 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vinuesa C. G., Linterman M. A., Goodnow C. C., Randall K. L., T cells and follicular dendritic cells in germinal center B-cell formation and selection. Immunol. Rev. 237, 72–89 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buch T., et al., A Cre-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor mediates cell lineage ablation after toxin administration. Nat. Methods 2, 419–426 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casola S., et al., Tracking germinal center B cells expressing germ-line immunoglobulin gamma1 transcripts by conditional gene targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7396–7401 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finney J., Yeh C. H., Kelsoe G., Kuraoka M., Germinal center responses to complex antigens. Immunol. Rev. 284, 42–50 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cirelli K. M., Crotty S., Germinal center enhancement by extended antigen availability. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 47, 64–69 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Awate S., Babiuk L. A., Mutwiri G., Mechanisms of action of adjuvants. Front. Immunol. 4, 114 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Shikh M. E., Pitzalis C., Follicular dendritic cells in health and disease. Front. Immunol. 3, 292 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinuesa C. G., Sanz I., Cook M. C., Dysregulation of germinal centres in autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 845–857 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morel L., et al., Genetic reconstitution of systemic lupus erythematosus immunopathology with polycongenic murine strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6670–6675 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Z., et al., Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Cdkn2c regulates B cell homeostasis and function in the NZM2410-derived murine lupus susceptibility locus Sle2c1. J. Immunol. 186, 6673–6682 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wittenbrink N., et al., Broad volume distributions indicate nonsynchronized growth and suggest sudden collapses of germinal center B cell populations. J. Immunol. 184, 1339–1347 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pikor N. B., et al., Remodeling of light and dark zone follicular dendritic cells governs germinal center responses. Nat. Immunol. 21, 649–659 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwickert T. A., Alabyev B., Manser T., Nussenzweig M. C., Germinal center reutilization by newly activated B cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2907–2914 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radovich J., Talmage D. W., Antigenic competition: Cellular or humoral. Science 158, 512–514 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pross H. F., Eidinger D., Antigenic competition: A review of nonspecific antigen-induced suppression. Adv. Immunol. 18, 133–168 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siegrist C. A., Aspinall R., B-cell responses to vaccination at the extremes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 185–194 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pihlgren M., et al., Unresponsiveness to lymphoid-mediated signals at the neonatal follicular dendritic cell precursor level contributes to delayed germinal center induction and limitations of neonatal antibody responses to T-dependent antigens. J. Immunol. 170, 2824–2832 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niu H., Sobel E. S., Morel L., Defective B-cell response to T-dependent immunization in lupus-prone mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 3028–3040 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lieberman L. A., Tsokos G. C., Lupus-prone mice fail to raise antigen-specific T cell responses to intracellular infection. PLoS One 9, e111382 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaya M., et al., Host response. Inflammation-induced disruption of SCS macrophages impairs B cell responses to secondary infection. Science 347, 667–672 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McAllister E. J., Apgar J. R., Leung C. R., Rickert R. C., Jellusova J., New methods to analyze B cell immune responses to thymus-dependent antigen sheep red blood cells. J. Immunol. 199, 2998–3003 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jang I. K., et al., Growth-factor receptor-bound protein-2 (Grb2) signaling in B cells controls lymphoid follicle organization and germinal center reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7926–7931 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.