Abstract

This article provides county-level estimates of the cumulative prevalence of four levels of Child Protective Services (CPS) contact using administrative data from the 20 most populous counties in the United States. Rates of CPS investigation are extremely high in almost every county. Racial and ethnic inequality in case outcomes is large in some counties. The total median investigation rate was 34.5%; the risk for Black, Hispanic, and White children exceeded 10% in all counties. Risks of having a CPS investigation were highest for Black children (32.9 to 62.8%). Black children also experienced high rates of later-stage CPS contact, with rates often above 20% for confirmed maltreatment, 10% for foster care placement, and 2% for termination of parental rights (TPR). The only other children who experienced such extreme rates of later-stage CPS interventions were American Indian/Alaska Native children in Middlesex, MA; Hispanic children in Bexar, TX; and all children except Asian/Pacific Islander children in Maricopa, AZ. The latter has uniquely high rates of late-stage CPS interventions. In some jurisdictions, such as New York, NY, (0.2%) and Cook, IL (0.2%), very few children experienced TPR. These results show that early CPS interventions are ubiquitous in large counties but with marked variation in how CPS systems respond to these investigations.

Keywords: child maltreatment, foster care, termination of parental rights, racial/ethnic inequality

Contact with Child Protective Services (CPS)—encompassing everything from an investigation to the termination of parental rights (TPR)—is common, unequally distributed, and potentially consequential for children. National data from the United States indicate that roughly 1 in 3 children will ever have a CPS investigation (1), 1 in 8 will ever experience confirmed maltreatment (2, 3), 1 in 17 will ever be placed in foster care (2, 4), and 1 in 100 will ever have parental rights terminated (5). These outcomes are especially elevated for Black children and, in the case of foster care placement and TPR, Native American children (1–5). Although it is unclear whether CPS contact causes poor outcomes or is merely associated with them, research nonetheless shows that children who have come into contact with CPS fare poorly on a range of outcomes (6, 7).

Existing data estimating the cumulative prevalence of contact with CPS are exclusively at the national (1, 2, 4, 5) or state (3, 8) level, with the exception of a small number of studies considering counties or neighborhoods in only one state (9, 10). Yet most decisions about whether to investigate a child maltreatment allegation, confirm that maltreatment occurred, place a child in foster care, or terminate parental rights happen not at the national or state level but at the county level (11). Comparative analyses suggest county CPS systems differ markedly in how they approach cases (12). Thus, national and even state data may mask materially consequential within- and between-locale differences.

We construct synthetic cohort life tables using data for almost all children living in the 20 most populous counties in the United States in 2014–2018 to provide county-level estimates of the cumulative prevalence of having a CPS investigation, having a confirmed maltreatment case, being placed in foster care, and having parental rights terminated. In so doing, we provide insights into how much place and race/ethnicity shape the rate of experiencing CPS contact.

Results

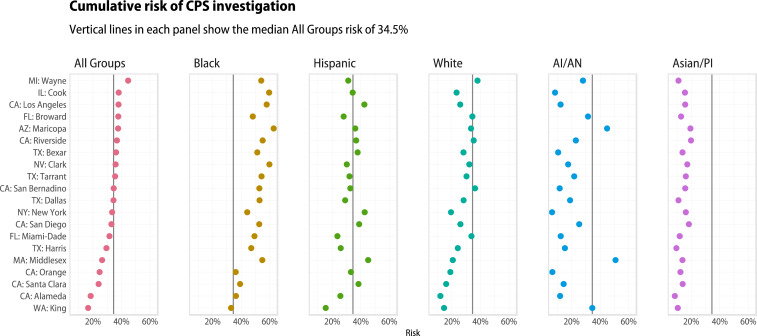

Fig. 1 presents results from synthetic cohort life tables estimating the cumulative prevalence of ever having a CPS investigation by age 18 y in the 20 largest CPS jurisdictions in the country. The median cumulative prevalence for these 20 jurisdictions was 34.5%. No jurisdiction had a total cumulative prevalence below 16%. One (Wayne, MI) had a total rate of over 44%. A CPS investigation is a pervasive event for US children living in major metropolitan areas.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative risk of CPS investigation by age 18 y in the 20 most populous counties in the United States for all children and children from five racial/ethnic groups, 2014–2018. Vertical lines in each panel show the median of 34.5% for all groups. Counties are ordered by risk of CPS investigation, with the highest risk for all groups at the top. AI, American Indian; AN, Alaska Native; PI, Pacific Islander.

Black children had consistently high rates of investigations, ranging from 32.9% in King County, WA, to 63.3% in Maricopa County (AZ). In most counties, having had a CPS investigation was a modal outcome for Black children. In 11 of the 20 counties, Black children had risks of investigation that exceeded 50%. Asian/Pacific Islander children had consistently lower rates of CPS investigations than any other group. Their highest rate was 19.8% in Riverside, CA, still roughly 40% below the median. White children tended to experience investigations in the 15 to 35% range. Hispanic children tended to experience investigations in the 25 to 40% range. American Indian/Alaska Native children experience low rates in most of these counties, but experience rates above 40% in two counties.

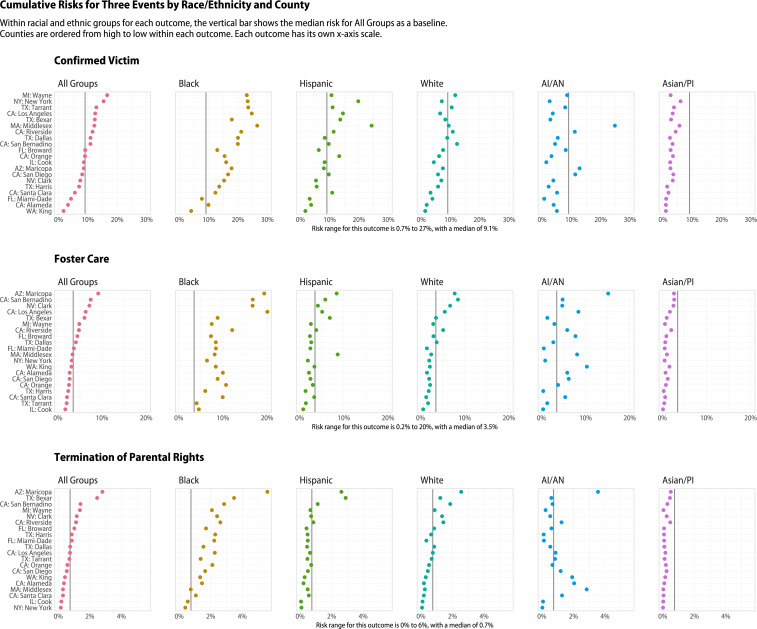

Fig. 2 presents estimates for confirmed maltreatment, foster care placement, and TPR. Total rates for all these events differed dramatically across counties. The disparity between the highest and lowest counties is 9.8:1 for confirmed maltreatment (Wayne, MI, vs. King, WA), 5.4:1 for foster care placement (Maricopa, AZ, vs. New York, NY), and 17.5:1 for TPR (Maricopa vs. New York), suggesting large differences in exposure across counties.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative risk of experiencing confirmed maltreatment, foster care placement, and TPR by age 18 y in the 20 most populous counties in the United States for all children and children from five racial/ethnic groups, 2014–2018. Vertical lines for the top (9.1%), middle (3.5%), and bottom (0.7%) panels show the median for all groups of experiencing each event. Each panel of the figure is ordered by risk of CPS event, with the highest risk for all groups at the top. AI, American Indian; AN, Alaska Native; PI, Pacific Islander.

The comparatively extreme rates of foster care placement and TPR in Maricopa, AZ, led to very high rates of both events for all children in that county, except Asian/Pacific Islanders. Aside from Maricopa, AZ, Hispanic and White children experienced elevated rates of later-stage CPS contact in few counties, with the exception of Hispanic children in Bexar, TX.

Black children, on the other hand, experienced exceptionally high rates of later-stage CPS intervention in nearly all counties. Rates routinely exceeded 20% for confirmed maltreatment (maximum: 26.5% in Middlesex, MA), 10% for foster care placement (maximum: 20.1% in Los Angeles, CA), and 2% for TPR (maximum: 5.6% in Maricopa, AZ). The highest cumulative risk of each of these events across all counties was also for Black children.

American Indian/Alaska Native children experience uneven patterns across counties. While their rates of TPR were well below the modal rate in most counties, rates were notably high in Middlesex, MA, where TPR for this group was nearly 3%, and Alameda, CA, and King, WA, where it was around 2%.

Discussion

The data suggest that having a CPS investigation is ubiquitous for US children (1) and that risks of later-stage CPS contact are also common for children from historically and/or economically marginalized populations (2–5). This article considered both between- and within-county variation across all four of these stages. This is a significant improvement over existing research, because virtually all critical decisions about later-stage CPS involvement happen at the county level (11, 12).

Consistent with national data (1), the results documented the ubiquity of having a CPS investigation for US children, especially Black children. For them, an investigation was a modal outcome in most of the counties we considered. Although there was variation across jurisdictions in the percentage of children experiencing this event, risks were consistently high.

There is a great deal less consistency when it comes to later-stage CPS contact. This was especially the case for TPR, where some counties terminated parental rights at rates shockingly higher than those in other counties. This is especially the case for Maricopa, AZ, and Bexar, TX, both of which terminated parental rights at over 15 times the rate of the counties that did so the least.

Although CPS investigations are common almost without exception in these 20 counties, there is significant heterogeneity in later-stage CPS involvement and, as importantly, in its prevalence across racial/ethnic groups. Future research should build on these descriptive results to better understand how differential handling of cases across counties leads to divergence in child well-being. Future considerations of these data should also consider disparities in levels of CPS contact by race/ethnicity, with special attention to disparities by race/ethnicity in transition probabilities between stages.

Materials and Methods

All results are based on the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data and the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System data. We use synthetic cohort life tables to estimate the cumulative prevalence of exposure to CPS by age 18 y. As with previous research using these methods (1–5), it is essential to differentiate first CPS contacts from higher-order contacts. Unique identification numbers in both datasets guarantee we are at no more than minimal risk for incorrectly considering children as experiencing their first CPS contact. Moreover, we focus on the 20 most populous counties, which are likely to have better data infrastructure than smaller counties. Thus, bias due to incorrectly counting children who have already experienced CPS contact is likely smaller in our analyses than in earlier national and state analyses.

Although we did not have a strict cutoff for population size, either for the total population or for specific racial/ethnic groups, it would be reasonable to be concerned about potential instability in point estimates for groups that form only a small part of the population (e.g., Native Americans), especially since the analyses are at the county level. In supplementary data (13), we show the population counts and counts of first CPS contact by race/ethnicity for each county. Even for Native Americans, the group with the smallest population in most counties, the total population never falls below 7,008 (for the pooled data over 5 y in Middlesex, MA), yielding a sufficiently large population to produce stable estimates even in the smaller counties.

The counties making up New York City report together because they are part of a unified CPS system that extends beyond county lines, and hence are presented together.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 1 R03 HD084883-01A1 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH to C.W., and by a Casey Family Programs grant to C.W. Funding for preparing the data for distribution was provided by a contract between the Administration for Children and Families and Cornell University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data Availability

All code used in these analyses is available at https://github.com/f-edwards/cps_lifetables_counties (13). Information on gaining access to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System data (see https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/request-restricted-data.cfm) and the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data (see https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/request-dataset.cfm) are available through the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov).

Change History

October 11, 2021: The text of the article and Figure 1 have been updated; please see accompanying Correction for details.

References

- 1.Kim H., Wildeman C., Jonson-Reid M., Drake B., Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. Am. J. Public Health 107, 274–280 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildeman C., et al., The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 706–713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi Y., Edwards F. R., Wildeman C., Cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment and foster care placement for US children by race/ethnicity, 2011–2016. Am. J. Public Health 110, 704–709 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wildeman C., Emanuel N., Cumulative risks of foster care placement by age 18 for U.S. children, 2000–2011. PLoS One 9, e92785 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wildeman C., Edwards F. R., Wakefield S., The cumulative prevalence of termination of parental rights for U.S. children, 2000–2016. Child Maltreat. 25, 32–42 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert R., et al., Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373, 68–81 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wildeman C., Waldfogel J., Somebody’s children or nobody’s children? How the sociological perspective could enliven research on foster care. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 40, 599–618 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam-Hornstein E., Needell B., Predictors of child protective service contact between birth and age five: An examination of California’s 2002 birth cohort. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 2400–2407 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong K., Neighborhood inequality in the prevalence of reported and substantiated child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 90, 13–21 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabol W., Coulton C., Polousky E., Measuring child maltreatment risk in communities: A life table approach. Child Abuse Negl. 28, 967–983 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldfogel J., Rethinking the paradigm for child protection. Future Child. 8, 104–119 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steen J. A., Duran L., Entryway into the child protection system: The impacts of child maltreatment reporting policies and reporting system structures. Child Abuse Negl. 38, 868–874 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards F. E., cps_lifetables_counties. GitHub. https://github.com/f-edwards/cps_lifetables_counties. Deposited 18 November 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All code used in these analyses is available at https://github.com/f-edwards/cps_lifetables_counties (13). Information on gaining access to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System data (see https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/request-restricted-data.cfm) and the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data (see https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov/datasets/request-dataset.cfm) are available through the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (https://www.ndacan.acf.hhs.gov).