To the Editor:

Acute kidney injury (AKI) and need for acute kidney replacement therapy (KRT) are frequent complications of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. During the first surge of the pandemic in the United States, AKI incidence was up to 40% in hospitalized patients.1,2 Among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 that developed AKI, 17%-19% required KRT, and in-hospital mortality was as high as 50%.1,2 Subsequently, multiple therapies have emerged to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection and our understanding of disease course has advanced.3,4 These improvements might explain the observed reduction in mortality rate in COVID-19 patients throughout the pandemic.5 In this evolving landscape, we sought to investigate temporal trends of AKI over 2020 and 2021 in a COVID-19 hospitalized population from a large health care system in New York City (NYC).

We analyzed the electronic health records from 5 major hospitals belonging to the Mount Sinai Health System throughout the 2020 pandemic. The research was performed under a Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board approval (20-00338), which allowed for analysis of patient-level data with a waiver of informed consent. We included all patients with age ≥18 years, polymerase chain reaction–confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, and admitted for >48 hours between March 1, 2020, and April 30, 2021. We excluded patients with known end-stage kidney disease on dialysis and kidney transplant recipients, as previously reported.2 Our primary outcome of interest was AKI defined according to creatinine-based KDIGO criteria. Baseline creatinine was defined as the most recent value obtained within 7-365 days prior to admission or, when unavailable, imputed on the basis of a Modification of Diet in Renal Disease estimated glomerular filtration rate of 75 mL/min, as done previously (the percentage of imputed creatinine values is reported in Table S1).2 AKI incidence was based on patient admission date; all patients were followed up to the occurrence of either discharge or death. We identified KRT by procedure codes and nursing flow sheets. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as previously reported.2

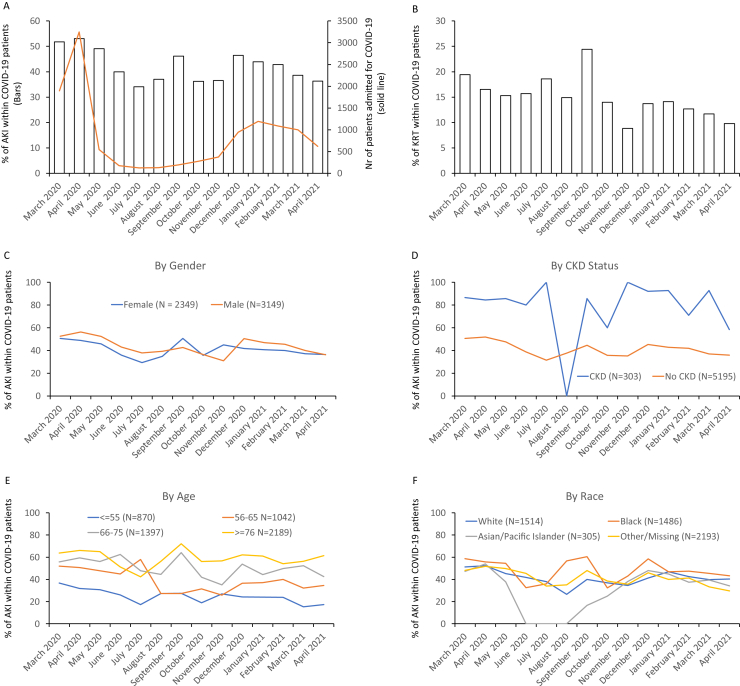

We analyzed data from a total of 5,498 patients; demographic characteristics are reported in Table S2. In the first 3 months of the NYC COVID-19 outbreak (from March 2020 to May 2020), AKI incidence in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 was between 49% and 53% (Fig 1A); incidence subsequently decreased to 34% in July and increased again with the second surge (November to February, peak 46.5%). When stratifying by AKI severity (Fig S1), we observed only a slight trend toward decrease of stage 3. Similarly, the proportion of patients needing dialysis decreased slightly (Fig 1B). This latter finding might be underestimated by the limited dialysis availability during the initial surge.

Figure 1.

Trends of acute kidney injury incidence through the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2020. (A) Bar graphs depict the percentage of patients suffering from acute kidney injury (AKI) within those hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The solid line depicts the total number of COVID-19 admissions from March 2020 to December 2020. (B) Percentage of patients requiring kidney replacement therapy (KRT) within the AKI group. (C-F) AKI incidence trends by (C) self-reported gender (M: male; F: female), (D) presence or absence of chronic kidney disease (CKD), (E) age category in years, and (F) self-reported race.

AKI incidence in men decreased from a maximum of 56.3% in April 2020 to a nadir of 37.8% in July; in female patients the peak was 50.6% in March 2020 and the lowest value was 29.4% in July 2020 (Fig 1C). The increased incidence of AKI reported in men at the beginning of the pandemic2 did not persist in the subsequent months. When patients were reclassified according to their CKD status, no clear trend was evident (Fig 1D). In the age-group analysis, younger ages (<65 years) showed a trend toward AKI reduction, while older patients did not (Fig 1E). Finally, after stratifying by self-reported race, we observed that African American patients had the highest incidence of COVID-19 AKI throughout the pandemic (Fig 1F). In white patients, the incidence was 45.4% and 13.6%, respectively.

In summary, using data from 14 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in a large, urban health care system, we showed that AKI incidence in COVID-19 patients has overall decreased. Also, Charytan et al6 observed a reduction of AKI incidence in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. However, their study included data from March to August 2020 and did not analyze the second NYC COVID-19 surge (from November 2020).7

Given its descriptive nature, this study cannot identify the causes behind the changes in AKI incidence over time. However, the following hypothesis might partially explain the observed trend. The comparison of the first (March 2020 - April 2020) and the second NYC surge (November 2020 - January 2021) shows that, despite the fact that estimated SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was 41% lower in the first wave (peak 7-day average 9,787 vs 16,612 cases/day), mortality rate was 402% higher (974 vs 194 cases/day).7 These data confirm a disproportionally higher morbidity and mortality during the first wave. As others have suggested,8 we believe that this discrepancy is mainly due to a dramatic underestimation of the real size of the first wave. In that timeframe the NYC health system probably tested and hospitalized only a small fraction of COVID-19 cases, likely the most severe ones.

Second, it is possible that the therapeutic approach to COVID-19 patients has progressively improved, preventing some episodes of AKI. Third, the populations affected by the first and second waves might have been clinically different; other authors have opposed this conclusion.9 Nevertheless, the incidence of AKI is still high in COVID-19; CKD patients have the highest risk of AKI, and racial disparities remain. Continued investigation is needed to further explore AKI in COVID-19 and to assess whether any of the newer therapeutic and management strategies have a causal role in preventing AKI in COVID-19.

Article Information

Authors’ Contributions

SG and AV contributed equally to this work. Research idea and study design: GN, LC, AV, SD; data acquisition: AV, LC; data analysis/interpretation: GN, LC, AV, SD, SC, AC; statistical analysis: SD, SKJ, LC, AV, ZF; supervision or mentorship: GN, LC, AV, EPB, JCH, BSG, AC. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Dr Lili Chan is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Renal Research Institute. Dr Steven Coca receives support from National Institutes of Health grants U01DK106962, R01DK115562, R01HL085757, U01OH011326, R01DK112258, and RRTI UG 2019. Dr Girish Nadkarni has received support from National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Career Development Award K23DK107908, and National Institutes of Health grants R01DK108803, U01HG007278, and U01DK116100.

Financial Disclosure

Drs Coca, He, and Nadkarni receive financial compensation as consultants and advisory board members for RenalytixAI and own equity in RenalytixAI. Dr Fayad has a Trained Therapeutix Discovery patents with royalties paid to Trained Therapeutix Discovery. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

To all of the nurses, physicians, and providers who contributed to the care of these patients. To the patients and their family members who were affected by this pandemic.

Peer Review

Received March 30, 2021 as a submission to the expedited consideration track with 2 external peer reviews. Direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form June 6, 2021.

Footnotes

Figure S1: Acute kidney injury stages over time according to the KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) classification.

Table S1: Percentage of imputed creatinine values over time.

Table S2: Demographic characteristics of studied individuals.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1; Tables S1-S2.

References

- 1.Zahid U., Ramachandran P., Spitalewitz S. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19 patients: an inner city hospital experience and policy implications. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51:786–796. doi: 10.1159/000511160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan L., Chaudhary K., Saha A. Mount Sinai COVID Informatics Center (MSCIC). AKI in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:151–160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthay M.A., Thompson B.T. Dexamethasone in hospitalised patients with COVID-19: addressing uncertainties. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1170–1172. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30503-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.htm [cited 2021 Jan 5]

- 6.Charytan D.M., Parnia S., Khatri M. Decreasing incidence of AKI in patients with COVID-19 critical illness in New York City. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(4):916–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The New York Times New York Coronavirus Map and Case Count [Internet] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/new-york-coronavirus-cases.html Accessed February 15, 2021.

- 8.Rǎdulescu A. Course of the first month of the COVID 19 outbreak in the New York State counties. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz L.I., Jones S.A., Cerfolio R.J. Trends in COVID-19 risk-adjusted mortality rates. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:90–92. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1; Tables S1-S2.