Abstract

We investigated compounds selected by molecular docking to identify a specific treatment for COVID-19 that decreases the interaction between angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2. Five compounds that interact with ACE2 amino acids Gln24, Asp30, His34, Tyr41, Gln42, Met82, Lys353, and Arg357 were evaluated using specific binding assays for their effects on the interaction between ACE2 with RBD. The compound labeled ED demonstrated favorable ACE2-binding, with an IC50 of 31.95 μM. ED cytotoxicity, evaluated using PC3 cells in an MTT assay, was consistent with the low theoretical toxicity previously reported. We propose that ED mainly interacts with His34, Glu37, and Lys353 in ACE2 and that it has an inhibitory effect on the interaction of ACE2 with the RBD of the S-protein. We recommend further investigation to develop ED into a potential drug or adjuvant in COVID-19 treatment.

Keywords: ACE2, COVID-19, Docking, Inhibitors of ACE2/RBD, SARS-CoV-2

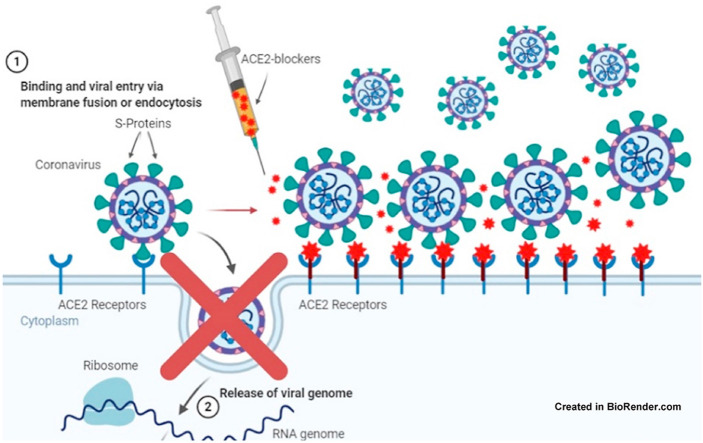

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to cause morbidity and mortality without specific treatment for the wide range of symptoms [[1], [2], [3]]. Different treatments have been proposed during this pandemic [4,5]. Moreover, new antivirals with different therapeutic targets have been developed, focusing on RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), polyproteins (3CLpro and PLpro) [[6], [7], [8]], spike protein (S-protein) [9,10], and the ACE2 region that interacts with RBD [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Many works have focused on developing new drugs against COVID-19, but no results have provided a therapeutic advantage to date.

ACE2 plays an important role, facilitating the movement of SARS-CoV-2 through the cell membrane. It was recently reported (December 2020) that observed mutations in RBD could increase the infection process and reduce the effect of vaccines [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. Furthermore, mutations in positions 452 and 501 have been reported to increase SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and the interaction of RBD with ACE2 [20,21]. Targeting the ACE2 interaction site allows researchers to choose this region as a therapeutic target to inhibit the interaction between ACE2 and the RBD. Several studies have targeted the interaction regions between the RBD and ACE2, performing docking for drug repositioning or using chemotherapeutic libraries (or using both methods) to search for drugs or compounds that can inhibit the interaction between RBD with ACE2 [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. In this study, we selected five compounds using molecular docking [11] and tested their interaction with ACE2 to determine their potential to inhibit its binding with RBD of the S-protein.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthetic compounds

Five compounds were tested using ID-Chembridge: 7782787 (EA), 7676800 (EB), 7956590 (EC), 7781334 (ED), and 7783270 (EE) [26] (Table 1 ). These compounds were previously reported as potential inhibitors of ACE2 and RBD binding [11]. The purity of the compounds reported by the manufacturer was greater than 95 %, which we verified by LC/MS. Stock solutions (1–10 mM) of each compound were prepared in DMSO.

Table 1.

Study ID, PubChem CID, ID-Chembridge Corp., Chemical name and structure of compounds tested.

EA: 2953970, 7782787, N,N'-[methylenebis (2-hydroxy-4,1-phenylene)]bis [2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)acetamide]

|

EB, 2947005, 7676800, 2,2'-{1,4-butanediylbis [(4-ethyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole-5,3-diyl)thio]}bis (1-phenylethanone)

|

EC, 2973584, 7956590, N,N′-bis{4-[(benzylamino)carbonyl]phenyl}malonamide

|

ED, 2953854, 7781334, N′,N''-[oxybis (4,1-phenylenecarbonyl)]bis (3-methoxybenzohydrazide)

|

EE, 2954039, 7783270, N′,N''-[oxybis (4,1-phenylenecarbonyl)]bis (2-chlorobenzohydrazide)

|

2.2. ACE2/RBD-SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor screening assay

We tested the selected compounds (ID-Chembridge: 7782787, 7676800, 7956590, 7781334, and 7783270) using the COVID-19 Spike-ACE2 Binding Assay Kit (RayBiotech cat: COV-SACE2) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO and tested in triplicate at the following concentrations: 100, 50, 30, 15, 5, and 2 μM. Briefly, the ACE2 protein was incubated with 250 μL of each compound in solution for 1 h with shaking. To RBD-coated 96-well plates, we added 100 μL of ACE2-compound solution. The plates were incubated at 2.5 h at room temperature with shaking, and then the plates were washed four times and incubated for 60 min with 100 μL of HRP-conjugated IgG. The plates were washed four times and incubated for 30 min with 100 μL of TMB One-Step Substrate Reagent, then we added 50 μL of stop solution to each well and read the absorbance of all wells at 450 nm immediately in a microplate spectrophotometer (Epoch; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). The positive control was ACE2 in DMSO. Decreased absorbance indicates that the ACE2–RBD interaction is inhibited.

2.3. Description of the molecular interaction of ED-compounds with ACE2 by docking

The atomic coordinates of ACE2 were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB: 1R42 and 7DF4). Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software was used to analyze the docking results [11]. We used the conformers of compounds with an inhibitor effect to describe the potential interaction in ACE2.

2.4. Cytotoxicity assay in PC3 cells cultures determined by MTT

The MTT viability assay was performed as described previously [27]. This assay is based on reducing yellow MTT (3-(4,5-diMethyl-2-Thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to formazan by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase, which is present only in living cells. The absorbance value of formazan is directly proportional to the number of viable cells [28].

PC3 cells in 96-well microplates (8000 cells per well) were treated for 48 h with concentrations of 50–300 μM of the ED compound. DMSO at a final concentration of 0.1 % was used as vehicle control. After treatment, the media was replaced with media containing MTT (0.5 mg/mL), and cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. The medium was removed, and formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO.

Finally, the plate was read at 570 nm. The assays were performed in triplicate and in three independent studies. The percentage viability was calculated according to the formula: % viability = [mean optical density (O.D.) treated cells × 100]/(mean O.D. control cells). The concentration corresponding to 50 % inhibition viability (IC50) was calculated by non-linear regression analysis (percentage of viability vs. log concentration) using GraphPad Prism ver. 7.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of a minimum of three independent experiments. Averages and standard deviations were calculated in Excel (Microsoft), and the IC50 of the ED compound was calculated using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Inhibition of ACE2-RBD binding

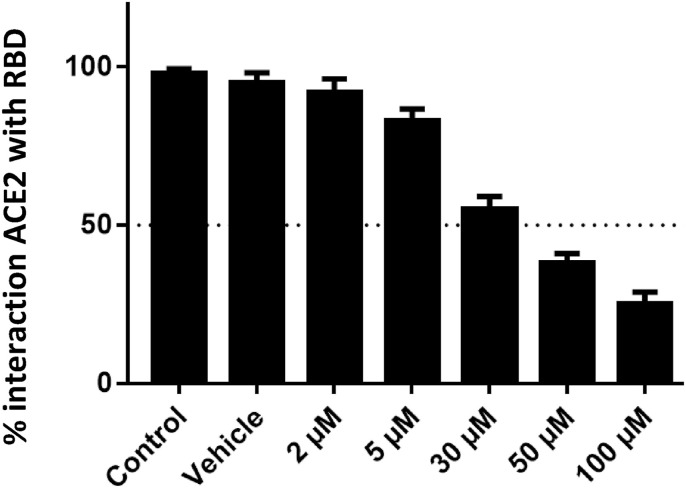

The ED compound (PubChem CID: 2953854) demonstrated an IC50 of 31.95 ± 3.98 μM (Fig. 1 ). The other compounds were not determined some inhibitor effect below 100 μM.

Fig. 1.

ACE2-RBD binding assay results, showing the percentage of interaction between ACE2 and RBD when exposed to 2–100 μM of the ED compound.

3.2. Description of the molecular interaction of the ED compound with ACE2 by molecular docking

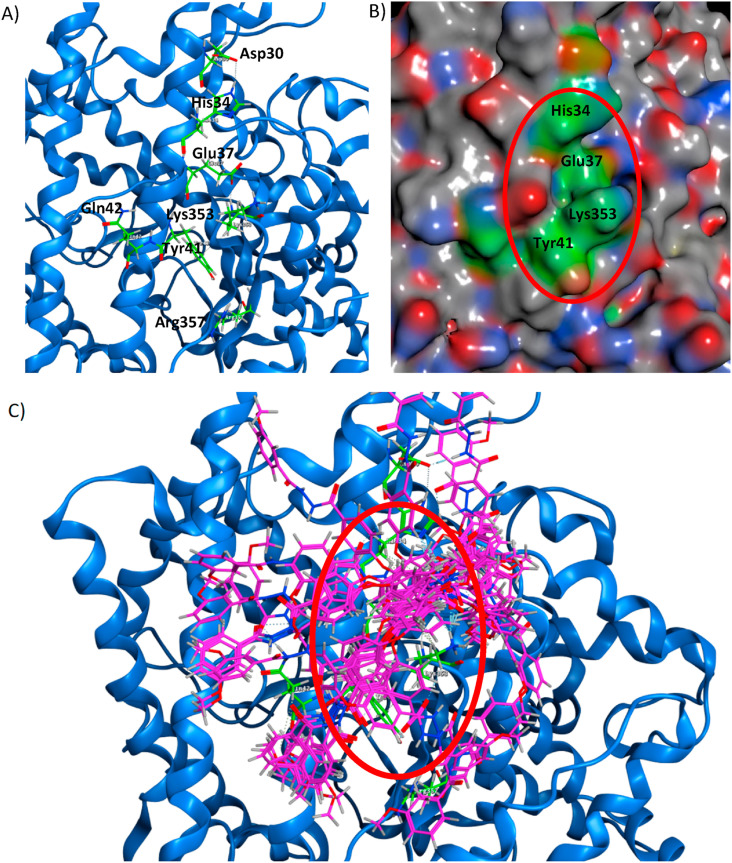

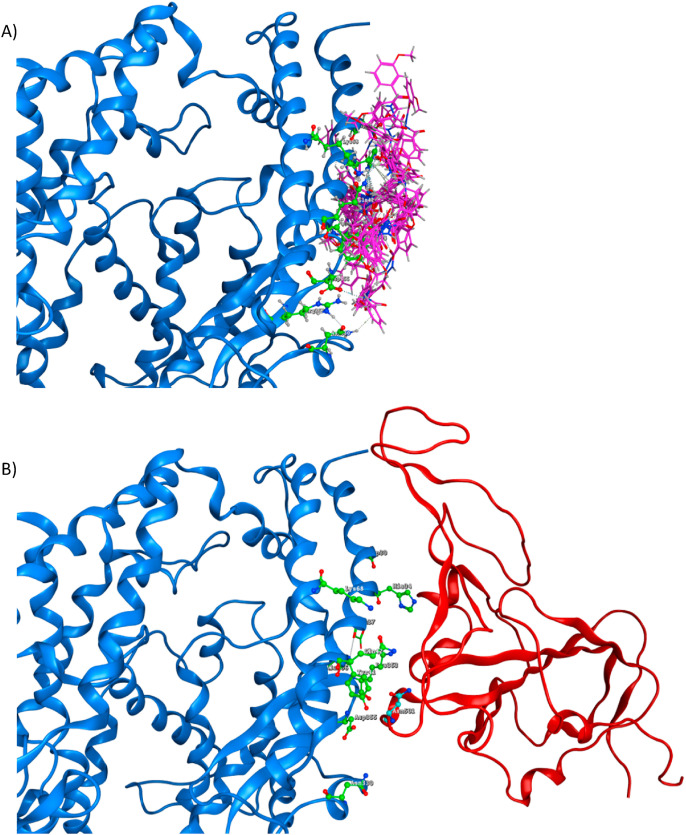

From the docking results [11], we described the probable interactions of the ED compound, and 18 conformers of the ED compound were used. The graphical interaction of each conformer is provided in the Supplementary Material (Table S1). We propose Asp30, His34, Glu37, Asp38, Tyr41, Gln42, Lys68, Asn330, Lys353, Asp355, and Ala386 ACE2 amino acids are the most important in interacting with the ED compound. However, 13 conformers interacted with the hydrogen bridge bond at His34, Glu37, and Lys353 amino acids (Fig. 2 , Table S2). The interactions of the ED compound were described previously (shown in Table S3) [11].

Fig. 2.

Potential site in ACE2 (blue) with main amino acids (green). A) The ACE2 Asp30, His34, Tyr41, Gln42, Met82, Lys353, and Arg357 amino acids as the potential docking site; the Lys353 is essential for interaction between ACE2 and RBD of the S-protein, B) Pocket of the potential site (red circle) and C) Pocket of potential site with 18 conformers of ED-compound (pink).

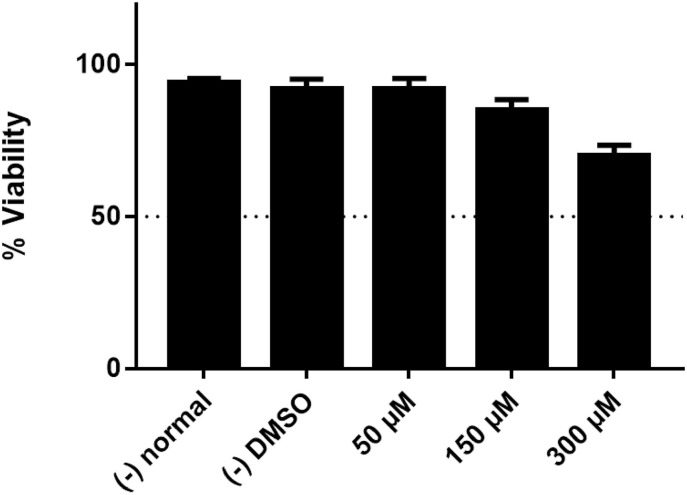

3.3. Cytotoxic effect of ED-compound by MTT viability assay

Mitochondrial activity, measured by MTT assay, indicates cell viability. We determined the cytotoxic effect of the ED compound in concentrations between 50 and 300 μM to determine culture viability. After 48 h of incubation, the 100 μM solution demonstrated no cytotoxic effect (similar results to the negative control and vehicle/DMSO). At 150 μM, the approximate cytotoxic effect was 12 %, and at a concentration of 300 μM, the cytotoxic effect was 25 % (Fig. 3 ). These results indicate that the ED compound may be safe in human cells, and other toxicity assays are needed to validate these results.

Fig. 3.

Percentage cytotoxicity in PC3 cultures after 48 h of incubation with ED compound concentrations between 50 and 300 μM.

4. Discussion

Effective treatments against COVID-19 are still under development, and there are multiple potential therapeutic targets against SARS-CoV-2 [5,[29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]].

In this study, we tested five compounds reported to inhibit the interaction between ACE2 and RBD in the S-protein [11]. These compounds were selected based on the docking directed to the amino acids in the crystallographic structure of the interaction between ACE2 (Gln24, Asp30, His34, Tyr41, Gln42, Met82, Lys353, and Arg357) and the RBD in the S-protein of SARS-CoV-2 [[35], [36], [37]].

In the inhibition tests, we identified that only the ED compound had an inhibitory effect up to 100 μM, and we determined an IC50 of 31.95 ± 3.98 μM. This result is notable as compounds or drugs repurposed for use against COVID-19 have demonstrated inhibitory effects of 10–40 % at concentrations between 10 and 30 μM [38]. These results suggest that those drugs participate in specific interactions.

To support the inhibitory effect of the ED compound, it is necessary to analyze the docking results, which showed that the ED compound has 18 conformers, each of which interacts differently with a potential ACE2 site. These results allowed us to identify the main amino acids that are important in the interaction of the 18 conformers of the ED compound with ACE2 (Asp30, His34, Glu37, Asp38, Tyr41, Gln42, Lys68, Asn330, Lys353, Asp355, and Ala386 amino acids, Tables S1 and S2). It is essential that 13 conformers interact with the hydrogen bridge bond with His 34, Glu37, and Lys353 in ACE2 (Fig. 2 and Table S2). We highlight the interactions generated close to His34 and Lys353, as these amino acids interact with Tyr453 and Asn501, respectively, in the RBD in the S-protein [35,39]. Currently, some variants of SARS-CoV-2 [21] have different consequences in the infection process. The ED compound may hinder the interaction with the region between Tyr453 and Asn501 in the S-protein, in which it is reported that the mutations in the positions 452 and 501 increase the Infectivity and the interaction between the RBD with ACE2 and decrease the effectiveness of vaccines [[16], [17], [18],20,21]. Therefore, our results indicate that this interaction site in ACE2 is significant as a therapeutic target to inhibit the interaction between ACE2 and the RBD (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

ACE2 (blue) residues Gln24, Asp30, His34, Tyr41, Gln42, Met82, Asp330, Lys353, and Asp355 (green). A) ACE2 with 18 conformers of the ED compound (pink), B) ACE2 interacting with RBD of the S-protein (red) and the amino acid in position 501 (Asn, Cyan).

The cytotoxicity results for the ED compound in PC3 cells are favorable, with no effect at a concentration of 100 μM. These results are consistent with previously reported theoretical toxicity data, so the ED compound has a high probability of being safe in humans, and the development of this drug against COVID-19 may continue.

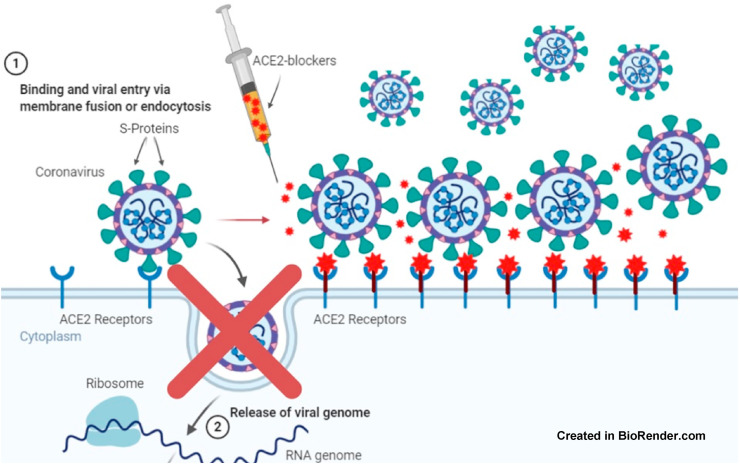

The ED compound was chosen by a docking directed to the specific region in ACE2 that is important in interacting with RBD, so at the molecular level, ED is highly specific in ACE2, providing a specific drug that prevents SARS-CoV-2 from interacting with human cells. This drug would not be antiviral since it would interact with ACE2 and might generate an inhibitory effect on the interaction with the S-protein of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 4). In addition, the ED compound might be used preventively, prophylactically, and during the COVID-19 infection process (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Blocking effect of a selective compound in ACE2, preventing cell entry of SARS-CoV-2.

The ED compound does not have any specific use or patent registered (PubChem CID: 2953854 [40]), and it is available for in vitro and other ACE2/RBD interaction assays. We propose that these results will contribute to developing a new drug that helps combat this pandemic.

5. Conclusions

We propose that the ED compound will provide the basis for developing a new drug that interacts with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Drugs based on ED could hinder or prevent the interaction of ACE2 with SARS-CoV-2. The ED compound has a good preliminary IC50 that significantly reduces the interaction of ACE2 with RBD and thus could hinder the COVID-19 infection process in humans. Cytotoxicity testing of the ED compound revealed it would likely be safe in humans. Therefore, it is necessary to continue the development of this drug against COVID-19.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful for the financial support from SIP-IPN México (20196821, 20200919), COFAA-IPN, NPTC-PRODEP-SEP, SNI-CONACyT, UABC, Dr. Octavio Galindo Hernandez, Dr. Mario Israel Oregel Cortez, and Dr. José Manuel Avendaño Reyes.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104719.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Li X., Chan J.F.-W., Li K.K.-W., Tso E.Y.-K., Yip C.C.-Y., Sridhar S., Chung T.W.-H., Chiu K.H.-Y., Hung D.L.-L., Wu A.K.-L., Chau S.K.-Y., Liu R., Lung K.-C., Tam A.R., Cheng V.C.-C., To K.K.-W., Chan K.-H., Hung I.F.-N., Yuen K.-Y. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in conjunctival secretions from patients without ocular symptoms. Infection. 2021;49:257–265. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01524-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chams N., Chams S., Badran R., Shams A., Araji A., Raad M., Mukhopadhyay S., Stroberg E., Duval E.J., Barton L.M., Hajj Hussein I. COVID-19: a multidisciplinary review. Front. Public Heal. 2020;8:383. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu Y., Sun J., Dai Z., Deng H., Li X., Huang Q., Wu Y., Sun L., Xu Y. Prevalence and severity of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127:104371. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C., Hui D.S.C., Du B., Li L., Zeng G., Yuen K.-Y., Chen R., Tang C., Wang T., Chen P., Xiang J., Li S., Wang J., Liang Z., Peng Y., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y., Peng P., Wang J., Liu J., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z., Qiu S., Luo J., Ye C., Zhu S., Zhong N. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valle C., Martin B., Touret F., Shannon A., Canard B., Guillemot J.-C., Coutard B., Decroly E. Drugs against SARS-CoV-2: what do we know about their mode of action? Rev. Med. Virol. 2020;30:1–10. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Leist S.R., Schäfer A., Won J., Brown A.J., Montgomery S.A., Hogg A., Babusis D., Clarke M.O., Spahn J.E., Bauer L., Sellers S., Porter D., Feng J.Y., Cihlar T., Jordan R., Denison M.R., Baric R.S. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G., De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calligari P., Bobone S., Ricci G., Bocedi A. Molecular investigation of SARS–CoV-2 proteins and their interactions with antiviral drugs. Viruses. 2020;12:445. doi: 10.3390/v12040445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J., Song W., Huang H., Sun Q. Pharmacological therapeutics targeting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, proteinase and spike protein: from mechanistic studies to clinical trials for COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1131. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benítez-Cardoza C.G., Vique-Sánchez J.L. Potential inhibitors of the interaction between ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 (RBD), to develop a drug. Life Sci. 2020;256:117970. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khelfaoui H., Harkati D., Saleh B.A. Molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations and reactivity, studies on approved drugs library targeting ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 binding with ACE2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1803967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grifoni A., Sidney J., Zhang Y., Scheuermann R.H., Peters B., Sette A. A sequence homology and bioinformatic approach can predict candidate targets for immune responses to SARS-CoV-2, cell host microbe. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ton A.-T., Gentile F., Hsing M., Ban F., Cherkasov A. Rapid identification of potential inhibitors of SARS‐CoV‐2 main protease by deep docking of 1.3 billion compounds. Mol. Inform. 2020 doi: 10.1002/minf.202000028. minf.202000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;80– doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. eabb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conti P., Caraffa A., Gallenga C.E., Kritas S.K., Frydas I., Younes A., Di Emidio P., Tetè G., Pregliasco F., Ronconi G. The British variant of the new coronavirus-19 (Sars-Cov-2) should not create a vaccine problem. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 2021;35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos J.C., Passos G.A. The high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 is associated with increased interaction force between Spike-ACE2 caused by the viral N501Y mutation. BioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.29.424708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luan B., Wang H., Huynh T. Molecular mechanism of the N501Y mutation for enhanced binding between SARS-CoV-2{\textquoteright}s spike protein and human ACE2 receptor. BioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.04.425316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.V’kovski P., Kratzel A., Steiner S., Stalder H., Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:155–170. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan A., Wei D.-Q., Kousar K., Abubaker J., Ahmad S., Ali J., Al-Mulla F., Ali S.S., Nizam-Uddin N., Sayaf A.M., Mohammad A. ChemBioChem; 2021. Preliminary Structural Data Revealed that the SARS‐CoV‐2 B.1.617 Variant's RBD Binds to ACE2 Receptor Stronger than the Wild Type to Enhance the Infectivity. cbic.202100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantón R., De Lucas Ramos P., García-Botella A., García-Lledó A., Gómez-Pavón J., González del Castillo J., Hernández-Sampelayo T., Martín-Delgado M.C., Martín Sánchez F.J., Martínez-Sellés M., Molero García J.M., Moreno Guillén S., Rodríguez-Artalejo F., Ruiz-Galiana J., Bouza E. New variants of SARS-CoV-2. Rev. Española Quimioter. 2021 doi: 10.37201/req/071.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang P., Zhong W., Wang Y., Wang Q., Xu Y., Li M., Li X., Zheng M., Chen L., Li H. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souza P.F.N., Lopes F.E.S., Amaral J.L., Freitas C.D.T., Oliveira J.T.A. A molecular docking study revealed that synthetic peptides induced conformational changes in the structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein, disrupting the interaction with human ACE2 receptor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;164:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Br B., Damle H., Ganju S., Damle L. In silico screening of known small molecules to bind ACE2 specific RBD on Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 for repurposing against COVID-19. F1000Research. 2020;9:663. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24143.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prajapat M., Shekhar N., Sarma P., Avti P., Singh S., Kaur H., Bhattacharyya A., Kumar S., Sharma S., Prakash A., Medhi B. Virtual screening and molecular dynamics study of approved drugs as inhibitors of spike protein S1 domain and ACE2 interaction in SARS-CoV-2. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2020;101:107716. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corporation, ChemBridge, (n.d.) http://www.chembridge.com/screening_libraries/

- 27.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6606682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisenbrand G., Pool-Zobel B., Baker V., Balls M., Blaauboer B., Boobis A., Carere A., Kevekordes S., Lhuguenot J.-C., Pieters R., Kleiner J. Methods of in vitro toxicology. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:193–236. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C., Zhou Q., Li Y., Garner L.V., Watkins S.P., Carter L.J., Smoot J., Gregg A.C., Daniels A.D., Jervey S., Albaiu D. Research and development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for COVID-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6:315–331. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuji M. Potential anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 drug candidates identified through virtual screening of the ChEMBL database for compounds that target the main coronavirus protease. FEBS Open Bio. 2020;10:995–1004. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J. Fast identification of possible drug treatment of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) through computational drug repurposing study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020;60:3277–3286. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elfiky A.A. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020;248:117477. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elfiky A.A. Ribavirin, remdesivir, sofosbuvir, galidesivir, and tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): a molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020;253:117592. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardoso W.B., Mendanha S.A. Molecular dynamics simulation of docking structures of SARS-CoV-2 main protease and HIV protease inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1225:129143. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;80– doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tai W., He L., Zhang X., Pu J., Voronin D., Jiang S., Zhou Y., Du L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.-H., Nitsche A., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carino A., Moraca F., Fiorillo B., Marchianò S., Sepe V., Biagioli M., Finamore C., Bozza S., Francisci D., Distrutti E., Catalanotti B., Zampella A., Fiorucci S. Hijacking SARS-CoV-2/ACE2 receptor interaction by natural and semi-synthetic steroidal agents acting on functional pockets on the receptor binding domain. Front. Chem. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.572885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walls A.C., Park Y.-J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.PubChem ED-compound. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2953854 n.d.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.