Abstract

Introduction:

Women’s active participation is important for inclusive water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) programs, yet gender roles that limit women’s access to formal education and employment may reduce their skills, experience, and capacity for implementation. This paper explores differences between men and women implementers of rural WaSH programs in implementation approaches, challenges, and sources of support for implementation, and success in achieving program quality outcomes.

Methods:

We interviewed 18 men and 13 women in community-based implementation roles in four districts of Nepal. We identified challenges and sources of support for implementation in four domains—informational, tangible, emotional, or companionship—following social support theory. We assessed successes at achieving intermediate implementation outcomes (e.g., adoption, appropriateness, sustainability) and long-term intervention outcomes (e.g., community cleanliness, health improvements).

Results:

Women used relational approaches and leveraged social ties to encourage behavior change, while men used formative research to identify behavior drivers and sanctions to drive behavior change. Women experienced stigma for working outside the home, which was perceived as a traditionally male role. Companionship and emotional support from other women and male community leaders helped mitigate stigma and lack of informational support. Women were also more likely to receive no or low financial compensation for work and had fewer opportunities for feedback and training compared to men. Despite lack of support, women were motivated to work by a desire to build their social status, gain new knowledge, and break conventional gender roles.

Conclusions:

Both men and women perceived that women were more effective than men at mobilizing widespread, sustained WaSH improvements, which was attributed to their successes using relational approaches and leveraging social ties to deliver acceptable and appropriate messages. Their skills for motivating collective action indicate that they can be highly effective WaSH implementers despite lack of technical experience and training, and that women’s active participation is important for achieving transformative community change.

Keywords: water, sanitation, and hygiene, WaSH, gender, implementation science, social support

Introduction

Women’s active participation is important for safe, effective, and inclusive water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) programs. Women and girls are disproportionately affected by cultural norms for modesty and privacy during defecation and hygiene (Caruso et al., 2015). They are typically the duty-bearers for WaSH-related tasks within the household, such as water collection (Graham et al., 2016) and child feces management (Majorin et al., 2019). These duties expose women to additional health risks, such as exposure to pathogens or injury from carrying heavy water containers (Sevilimedu et al., 2017; Sorenson et al., 2011). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) recognize the importance of women’s participation in WaSH through Goal 5, which sets targets for increasing women’s participation in leadership roles and decision making, and ending discrimination against women and girls, and Goal 6, which calls for universal access to WaSH “for all” and emphasizes “paying special attention to the needs of women and girls” (United Nations, 2015).

WaSH programs often rely on women for implementation at the local level. Community-based sanitation programs in low- and middle-income countries often emphasize recruitment of natural leaders from within the community and inclusion of women (WHO, 2018), and many countries have incorporated WaSH activities into the duties of female community health volunteers (female CHVs or FCHVs) (Perry et al., 2016). FCHV programs have extended basic health services to poor, rural areas that otherwise have little or no access (Bhutta et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2014). FCHVs are well suited to deliver health messaging to other women on sensitive topics such as menstruation that would be taboo for male healthcare providers (El Arifeen et al., 2013; Mumtaz et al., 2013; Panday et al., 2017). Mobilizing women’s groups for participatory learning and action has been shown to reduce gender inequalities that impede access to proper care and improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes (Perry et al., 2014; Prost et al., 2013).

Women’s active participation in WaSH and other natural resource management committees has been found to improve community trust in fee collection and financial management (Kelly et al., 2017), sustainable service delivery (Hoque et al., 1996; Westermann et al., 2005), collaboration and conflict management (Westermann et al., 2005), and recognition and resolution of problems in the community (Kelly et al., 2017). Women are often selected as implementers for community-based programming because they are familiar with the local context, well integrated into community social networks, and able to speak with other women on sensitive health topics (WHO, 2018).

However, recruiting women implementers from local communities has challenges. Communities targeted for health and development programs often have lower levels of formal education and other socioeconomic indicators (Kane et al., 2016). Gender norms that limit women’s participation in formal education and employment can reduce their experience, skills, and capacity to effectively deliver health programming (Panday et al., 2017; Sarin and Lunsford, 2017). Furthermore, women may lack agency to participate in WaSH implementation (Wali et al., 2020) or be nominally included without valuing their contributions and concerns (Yerian et al., 2014). Although documentation is limited, some evidence suggests that meaningful inclusion of women in community-based implementation can improve the quality of programs, provided they receive appropriate support (Bhutta et al., 2010).

The purpose of this study was to explore how the gender of community implementers influences implementation at the local level for rural WaSH programs in Nepal. Specific objectives were to describe differences between men and women implementers in implementation approaches, challenges, and sources of support for implementation, and success in achieving program quality outcomes at the local level. We discuss the implications of these differences for improving program implementation, including opportunities to strengthen training and feedback systems, leverage women’s social ties within communities, and reconsider compensation of unpaid workers.

Methods

Study design

We collected data through interviews with WaSH implementers in four districts in Nepal (Siraha, Mahottari, Surkhet, and Salyan) from June to August, 2019. Interviews were conducted as part of a larger study on quality improvement and innovation in rural WaSH, which included implementers from the regional to community levels. Here, we analyzed a subset of interviews from men and women in community-based implementation roles to understand how implementers perceive approaches, challenges, support, and successes at the local level.

Conceptual frameworks

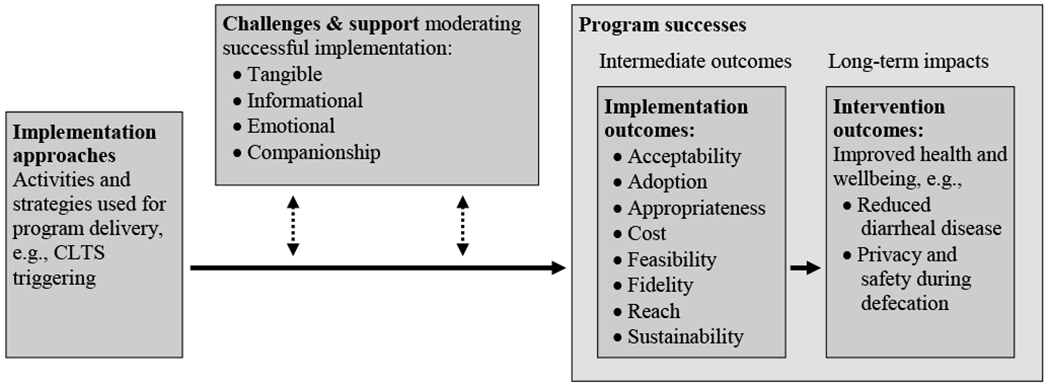

Implementation approaches are the activities and strategies used for program delivery. In implementing these approaches, men and women experience various challenges that hinder successful implementation and sources of support to mitigate those challenges. When challenges can be mitigated and adequate support is received, implementation approaches are expected to yield program success in terms of intermediate implementation outcomes (e.g., adoption and sustained practice of WaSH behaviors) and long-term impacts on target intervention outcomes (i.e., improvements in health and wellbeing). Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model that we developed for this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of relationships between implementation approaches, challenges and sources of support for implementation, and program successes. Implementation approaches are expected to achieve program success measures where they are evidence-based, contextually appropriate, and receive appropriate support to overcome challenges. The model combines elements of social support theory (Langford et al., 1997) to describe challenges and support, and implementation outcomes and long-term impacts (Proctor et al., 2011) to describe successes.

We hypothesized that gender would influence the implementation approaches used by men versus women and the challenges and support systems experienced when implementing these approaches. In turn, we hypothesized that these approaches, challenges, and support systems would influence success at achieving implementation and intervention outcomes. We assessed implementation approaches, support and challenges, and implementation and program quality outcomes for all participants following the frameworks described below, then compared differences between men and women.

Implementation approaches

Activities conducted by village-level implementers primarily comprised behavior change messaging delivered in household and community settings. These activities in Nepal draw heavily from a community-led total sanitation (CLTS) approach (Department of Water Supply and Sewerage, 2011). CLTS uses participatory activities designed to elicit negative emotions such as shame and disgust at open defecation to “trigger” behavior change and collective action to make the community open defecation free (ODF) (Kar and Chambers, 2008). Similar approaches for behavior change triggering are also used to promote hygiene and other WaSH behaviors (e.g., food hygiene) post-ODF. Following triggering, local-level implementers conduct household and community-level follow up activities to give behavior change messages and create demand for WaSH.

For this study, we assessed which CLTS and related behavior change and demand creation activities were conducted by implementers, plus any alternative or additional activities delivered to households or communities. We did not assess implementation approaches related to capacity building or coordination of stakeholders, which were occurring at the local level but were rarely conducted by participants in our sample.

Challenges and support systems

We applied social support theory to categorize challenges and sources of support for implementation as either informational, tangible, emotional, or companionship. Informational support provides knowledge or guidance, typically to assist with problem solving. Tangible support provides physical goods, services, or money as a form of direct assistance. Emotional support provides encouragement through making an individual feel valued or self-confident, such as through expressions of empathy, concern, or caring. Companionship support provides a feeling of social belonging or presence of companions to engage in shared activities (Langford et al., 1997).

Social support theory has been used to explore determinants of successful implementation of health behaviors by lay individuals, households, and communities (Heaney and Israel, 2008; Kelly et al., 1991), similar to lay persons who serve as natural leaders under CLTS-style programs. Social support is particularly relevant for community-based WaSH implementers, who live in the community in which they work and have strong social ties to program recipients.

Program successes

We used outcomes defined by Proctor et al. (2011) as measures of program success: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability. Table 1Error! Reference source not found. provides definitions. Proctor’s framework proposes that implementation outcomes are precursors to achieving intervention outcomes, and that intervention outcomes may only be achieved if a program is implemented well. In the case of WaSH programs, relevant intervention outcomes include reductions in diarrheal disease or child mortality.

Table 1.

Implementation outcomes as measures of program quality. Adapted from Proctor et al. 2011.

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acceptability | Perception that a given WaSH program or its component parts is agreeable and satisfactory |

| Adoption | Intention, decision, or action to uptake a WaSH behavior or technology |

| Appropriateness | Perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the WaSH program with context, or perceived fit of the program to address a specific issue or problem |

| Cost | Cost of implementation efforts |

| Feasibility | The extent to which the WaSH program can be successfully delivered or used within a given context |

| Fidelity | The extent to which the WaSH program is delivered as originally developed and specified in program plans and protocols |

| Penetration | Coverage area and intensity of exposure to the WaSH program among the target population |

| Sustainability | The extent to which WaSH behaviors and technologies are maintained and institutionalized within the target population |

Study setting

WaSH implementers in Nepal include a diverse range of government, international and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), multilateral organizations, private sector, and civil society organizations, such as women’s, mothers’, and journalist groups. We consider WaSH implementers to be anyone who participates in the delivery of program activities directly to beneficiary households (e.g., behavior change messaging) or the supervision, regulation, or technical support of these activities.

Sanitation and hygiene delivery in Nepal are governed at the federal level by the National Sanitation and Hygiene Master Plan. The Master Plan outlines responsibilities for different levels of government and defines “guiding principles”—such as representation of women on steering committees at a “minimum of 33% of the members, as appropriate.” The details of specific activities or program plans are determined at the subnational level (Department of Water Supply and Sewerage, 2011).

District committees called “WaSH coordination committees” are responsible for supervising and harmonizing activities of implementers. Municipal committees plan and coordinate implementation activities in partnership with NGOs. Coordination committees are chaired by elected government officials, such as mayors, vice-mayors, and ward presidents. Elected government officials participate in the supervision and policy regulation but rarely deliver activities directly to beneficiary households. The majority of day-to-day behavior change programming at the local level is delivered to households by paid staff from local NGOs and unpaid community volunteers, including FCHVs and women’s and mothers’ groups. Technical support is provided by government employees, who are non-elected, hired specifically for their technical expertise. Multilateral agencies and international NGOs also provide technical support, including the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations Human Resettlement Program, and the SNV Netherlands Development Organization (Adhikari, 2012).

Men outnumber women in WaSH implementation particularly for roles in district, regional, and national supervision; private sector jobs for construction and small business owners; and engineering or technical jobs (Wali et al., 2020). Women more often fill unpaid roles at the local level as FCHVs and women’s and mothers’ group members. FCHVs, women’s, and mothers’ group members may receive reimbursement or a small stipend to cover travel and food allowances but otherwise do not receive formal wages (Khatri et al., 2017).

Study population and recruitment

Within each district, a program coordinator who had lived and worked in the district for at least the past five years assisted with recruitment. Program coordinators were employees of local or international NGOs. Their duties included supervising teams of NGO staff and unpaid volunteers (e.g., FCHVs, women’s groups) across multiple villages and liaising with government and other partners.

Program coordinators were briefed on the research purpose and asked to identify a list of individuals who were highly involved in WaSH delivery at the district, municipal, and sub-municipal levels. From this list, we purposively sampled participants to represent a range of perspectives from government, multilateral organizations and NGOs (hereafter “development organizations”), and civil society organizations. When both men and women were available for interview for a particular stakeholder role, we preferentially recruited women to maintain a more equal gender balance.

For this study, we defined local-level as implementers at the sub-district level. We excluded regional- and national-level implementers, as their challenges, support, and successes differed substantially from those experienced at the local level. We also excluded participants from roles filled exclusively by men in the study sample—specifically WaSH technicians and engineers, masons, journalists, and small business owners.

Data collection

A research team comprised of one interviewer and one note taker conducted interviews in private offices or meeting rooms at participants’ workplace, or at the home or a nearby community center for participants without a formal office. During interviews, we asked participants to describe a novel WaSH solution or approach they used to improve program quality. We identified successes through questions that asked participants to describe whether they perceived their solution to be successful and how they defined and measured success, as well as questions that asked participants to describe successes and challenges for implementation and program improvement overall. We identified challenges and sources of support through questions that asked participants to describe barriers or facilitators to implementing and sustaining their solutions. Where participants described difficulties in implementing or sustaining solutions, we probed to explore sources of support for overcoming those difficulties.

Interview guides were developed in English, translated into Nepali, and pre-tested in a district bordering Siraha. Based on pre-testing, we reworded and reordered questions to improve the guide’s ability to elicit information on key concepts and question flow. We also iteratively revised the interview guide throughout data collection to explore emergent themes. Interviews lasted approximately one hour. We conducted interviews in English, Nepali, Hindi, or Maithili, following the preference of the participant. We audio recorded interviews where participants gave permission (n=27, 87%) and transcribed recordings directly into English for analysis.

We also asked participants to complete a brief demographic questionnaire to identify their job title, years of work experience, and gender.

Analysis

We conducted template analysis using NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) for coding. We coded for a priori themes for implementation approaches as CLTS, behavior change, and demand creation activities. We coded challenges and sources of support in four domains (informational, tangible, emotional, and companionship) following social support theory (Langford et al., 1997). Finally, we coded successes at achieving the eight implementation outcomes described in Table 1 and a single code for intervention outcomes encompassing health improvements in WaSH-related diseases.

We developed an initial template for analysis using a subset of six transcripts, revising codes for a priori themes, and developing inductive codes for emergent themes, as necessary. We then applied the template to an additional six transcripts, iterating the reflection and revision process, before proceeding to coding the full dataset. After coding all interviews, we sorted codes by participants’ self-identified gender to examine similarities and differences across men and women.

Ethics

This study was ruled as non-human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (IRB # 19-0945). Local approval for study activities was obtained from the Nepali Ministry of Water Supply. Participants were informed of the study purpose and provided written consent before enrollment.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our sample comprised 18 men and 13 women (Table 2). Participants were primarily elected officials (n= 6 men, 3 women) and development organization employees (n=8 men, 3 women). Men ranged in age from 30 to 62 years (median 40.5) and had served an average of 3.0 years in their current implementation role. Women ranged in age from 23 to 46 years (median 38) and has served an average of 4.6 years in their current implementation role. Women more commonly held unpaid non-elected roles (n=6, 46%) compared to men (n=2, 11%).

Table 2.

Participant demographics

| Number of participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men (n= 18) | Women (n= 13) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20-29 | 1 | 2 |

| 30-39 | 8 | 5 |

| 40-49 | 4 | 6 |

| 50+ | 5 | - |

| Employment position | ||

| Elected officials† | 6 | 3 |

| Government employees | 1 | - |

| NGO or multilateral employees | 8 | 3 |

| Teacher or school official | 1 | 1 |

| Social activist† | 1 | - |

| Disabled persons’ organization representative† | 1 | - |

| Female community health volunteers† | - | 3 |

| Women’s or mothers’ group members† | - | 3 |

| Years in current position | ||

| 0-2 | 8 | 7 |

| 3-5 | 9 | 3 |

| >5 | 1 | 3 |

| Location | ||

| Mahottari | 5 | 3 |

| Salyan | 2 | 4 |

| Siraha | 8 | 1 |

| Surkhet | 3 | 5 |

Denotes participants in unpaid roles.

We use the term “unpaid women” to describe women in non-elected, unpaid roles as FCHVs and women’s and mothers’ group members. We use the term “government implementers” to describe the combined efforts of government elected officials and employees, or differentiate between elected officials versus government employees as applicable.

Implementation approaches

Activities and messages used by community-based implementers were typically designed by development organizations. Content was similar to triggering techniques used under CLTS, designed to raise negative feelings about open defecation and awareness of its dangers. In some cases, content had been adapted to other settings, such as school-led total sanitation, where children were given similar messages and asked to pressure their parents to build toilets.

When WaSH activities were first implemented, implementers perceived strong community norms for open defecation and reported that households were often unwilling to construct toilets without a subsidy. Both men and women implementers perceived that messaging strategies were often initially unsuccessful at motivating behavior change and toilet construction, and WaSH activities did not meet participants’ expectations for achieving rapid, community-wide behavior change. Responses to poor perceived success varied across government versus development organizations and men versus women.

Men from government in our sample commonly reported using “pressure” approaches. They insisted that individuals and households must comply with WaSH policies to meet government regulations. When these messages did not meet expectations for achieving rapid toilet construction, sanctions were the used, such as threatening to restrict or restricting government services (e.g., work permits and citizenship papers) for non-toilet owners or arresting and fining open defecators. Men perceived that these approaches created tension with the community:

“…Women and people used to curse me and abuse me. We have also abused them and dishonored them. We also seek the help of police to control them.” -man, local government official

Technical advisors from development organization did not endorse sanctions approaches. Men in development organizations instead reported adjusting the content of messaging to more effectively motivate behavior change. For example, one man used radio jingles with voices of local people and two men developed new slogans to address locally relevant behavioral motivators.

In contrast to “pressure” approaches, women in all implementation roles used “convincing” approaches when they perceived households to be resistant to behavior change. Women did not demand that households must change behavior, but rather emphasized the benefits of WaSH for individuals, other members of the household, and community at-large. Women also recruited others in the community to show their support and deliver messages in groups:

“When we say to the women, ‘Sister, this toilet is for you,’ they agreed and made the toilet. If the women do not understand, then we convince the mother in law by saying, ‘Aunt, please make the toilet. If you made the toilet, it will be good for your daughter in law.’ We convince the daughter in law by saying, ‘It will be good for your son and daughters. Please look after the child and their health.’” -woman, development organization local implementer

Challenges and sources of support

Challenges for implementers arose due to differences in implementation approaches taken by men versus women, community and peer responses to these approaches, and the variance in support received to cope with challenges. The following sections categorize and describe these differences following the four domains of social support theory: informational, tangible, emotional, and companionship.

Informational support

Participation in program planning and training

Participants in all districts recognized women’s participation in coordination committees as important. However, large committees, particularly at the district level, were perceived as unwieldy and inefficient, so smaller subcommittees were often formed for developing work plans. These committees included primarily government implementers and development organization technical advisors—roles typically filled by men. Our sample included three women elected government officials at the sub-municipal level, but they rarely were invited to participate in these subcommittee meetings at the municipal or district level.

No women reported participating in subcommittees where high-level planning occurred. Instead, they participated in meetings to receive training on how to deliver and monitor program activities that had already been designed. For women in unpaid roles, trainings typically lasted one day, with some lasting up to three days. One woman conducting training for local mothers’ groups described how indicators for WaSH behaviors such as toilet use and handwashing were complex and difficult to understand with little training:

“I took the training from the district and then give training to the mother groups. I have a banner of Total Sanitation [post-ODF WaSH promotion activities], and I used it to educate them. In the banner there are many pictures.… They could not understand all the indicators at once.” -woman, elected official and former development organization implementer

Government implementers often overestimated FCHVs’ knowledge and training. Government implementers relied on FCHVs to support developing program plans. However, FCHVs were not confident in their ability to design, deliver, and improve messages independently. In one area where development organization-supported programs had ended and no technical advisors were available, FCHVs and other community-based workers with little formal WaSH training were the primary source of technical expertise:

“We have not yet given the technical knowledge to the tole [small municipal sub-unit]… [FCHVs and] health workers have the knowledge of sanitation and hygiene.” -woman, local government representative

Systems for feedback and troubleshooting

Men and women employed by development organizations described the most robust communication and information sharing for addressing implementation challenges. They shared information between workers across geographic areas through phone and social media groups and met locally to discuss progress and challenges towards achieving program targets and to share good practices.

Outside of development organizations, men typically had more robust systems for feedback and troubleshooting. Men in government described participating in committees with representatives from other municipalities, where they would share progress and troubleshoot problems. Technical advisers and program supervisors from development organizations, who were predominately men, also participated in these committees.

Women in unpaid roles were less integrated into systems for feedback and troubleshooting. In some areas, women in unpaid roles reported challenges to municipal WaSH committees but were rarely engaged in developing solutions. In some cases, they received ongoing support for improving the content of program activities from a development organization or government adviser. However, this support was less stable and strongly linked to presence of funded programs, as technical advisors often left program areas or were reassigned to other projects when funding ended. One FCHV described how she was unsure of the quality of her work, because she had never received feedback:

“I cannot say that all the works I have done are good because I have not seen some work output. I do my best, but there may be a chance that I am doing wrong. For example, if someone tells me that I have done wrong, then I can improve. Until now, no one has said that I have done anything wrong.” -FCHV

Exposure to external learning and experience

Men had more prior employment experience prior to holding their current position and had worked more years in with their institution compared to women (6.6 versus 5.0 years). They described experiences working on previous programs or in other areas, which they applied for improving program quality in their current positions:

“Our community was very backward. We used to go to Kathmandu, India, and other places. We have observed about the drainage system and other many things. And by seeing all these we have put the plan to the rural municipality.” -man, social activist

In contrast, most women had little to no prior work experience before taking their current position. One woman, who was president of her local mothers’ group, described how mobilizing women for WaSH campaigns was difficult because women had received little formal education, and some were “very young because of the early child marriage.” Another woman described how opportunities to learn were limited because no other development organizations were working locally:

“If they [other development organizations] came, we would get a chance to learn about new approaches. What is needed for the community, only we cannot decide. If other organizations come, their recommendation and feedback will help.” -woman, development organization local implementer

Tangible support

Insufficient funding and resources to deliver program activities was a challenge consistently reported across men and women. However, women were more likely to work as unpaid volunteers (46% of women versus 11% of men for non-elected positions in our sample). Programs relied heavily on FCHVs, women’s and mothers’ groups to conduct house-to-house behavior change activities and monitoring but did not offer formal wages to compensate their work. Unpaid women sometimes received allowances for snacks or travel, but two FCHVs indicated that these allowances were insufficient to cover the costs of their duties.

Four women in unpaid positions described challenges with balancing other responsibilities, such as managing domestic responsibilities in the home or field, or other income-generating activities. One FCHV indicated that with her time commitments to deliver non-WaSH programming under the FCHV curricula (e.g., contraceptive education) and hold paid employment, WaSH messages were only added to her work agenda seasonally, or as needed during water-borne disease outbreaks. One unpaid woman indicated that if she were paid, she could dedicate more time to WaSH work.

Unpaid women reported feeling less responsibility to improve program activities, because this was the responsibility of development organization workers who paid employees with more expertise. While unpaid women indicated that they would be willing to dedicate more time and effort to WaSH activities if they were paid, benefits such as increased opportunities for training and building social networks and status outside the home were still sufficient incentives to engage in WaSH work part-time.

Emotional support

Women implementers in all roles faced stigma for taking formal employment outside the home, which was perceived to violate traditional gender roles of women working only domestically. Stigma was particularly strong when programs were first implemented and decreased over time as communities perceived improvements to health and environmental cleanliness. This stigma was similar across women in both formal paid implementation roles and unpaid volunteers. Five women described receiving “abusive” words or confrontational reactions from men when delivering program activities. Particularly when programs were first implemented, these women reported criticism for attempting to educate and change behavior of men, which was perceived to overstep women’s authority. One woman was told that her work disrespected her husband and family:

“Some say face-to-face that, ‘You are rubbish, you only have the job to roam here and there. Your husband cooks the food by himself. You only roam here and there, and you do not respect your husband.’ It was most challenging for me during the working period. All people laugh on me. Some in front, some in back. Many abuse me” -woman, development organization local implementer

In response to this criticism, women received support from family, development organizations, and progressive community leaders who publicly endorsed their work. One woman development organization implementer reported that her husband called a meeting of other men in the village to ask that they “at least hear her” before criticizing, which caused a positive response once men recognized the benefits of the program. For other women, development organizations spoke with community men to mitigate stigma:

“[Development organization workers] have said, ‘You have done good work. We will look after those people who have abused you,’ and after they have said something to them, and now there is no such issue.” -FCHV

Women perceived that criticism decreased as communities observed improvements in community health and cleanliness, at which point women reported that they were recognized and praised for their work by community members. In lieu of compensation, unpaid women often received formal recognition for their work from local government, in the form of appreciation letters, ceremonies, and small gifts, such as shawls, which motivated them to continue working.

Themes related to emotional challenges and support were less commonly raised among men in our study sample. No man reported facing emotional challenges specifically related to their gender. Emotional challenges faced by men were typically experienced in relation to specific activities that they perceived to have low community acceptance, often sanctions-based approaches.

Companionship support

Companionship support through group messaging strategies

Companionship support was an important coping mechanism for women in response to many types of challenges. When faced with households resistant to behavior change messaging, the most common response from women was to recruit others to revisit households and deliver the same messages in a group. Groups were perceived to have more persuasive power than individuals. Group messaging strategies were particularly important for women in unpaid roles with less access to informational support. For these women, group messaging was the primary strategy for improving implementation, rather than refining the content of messages. Groups were commonly formed of women’s peers from the community, particularly women’s and mothers’ group members:

“When the challenges came, they [women] do not move back. Their meeting was continuous, and unity was their strength. When a woman has problems, all the women move to that house and sort out that problem by explaining to them. They go in the groups and convince other people, that it is the benefit for the community, it is the benefit for us, it is for family. And this how people have gradually changed.” -man, development organization local implementer

In some instances, women would also recruit support from men from development organizations, elected leaders, or informal opinion leaders, who were perceived to hold more power to enforce messages:

“We approach the community with the elected members, and the people follow them. If a ward-WaSH coordination committee makes any decision, the ward members have to follow…” -woman, development organization local implementer

Women proud of their achievements, and wanted to support other women to demonstrate that they could be skilled WaSH implementers. One woman who chaired a local all-women WaSH committee described the committee’s accomplishments despite a man who questioned their ability to succeed:

“He does not want to support the women, and then we have decided that we will do anything to show this man that we are not so much weak. And we can run the committee without the men and make changes in the community. This is how we have done. And we are successful. You can ask the people that our drinking water committee is one of the best drinking water committees in this area. Now the women are supporting me very much.” -woman, local elected official

Companionship support from peers was less important to men. None described using group messaging approaches as a strategy to cope with challenges.

Political support and rivalries

Men reported companionship challenges from political rivals who were unwilling to support or would actively undermine WaSH efforts. One development organization implementer reported that the locally elected leader refused to conduct activities with him and “create a pressure on [his] people” out of fear it would affect his re-election chances. Another man elected offical attributed WaSH budget shortfalls to political rivalries. In some cases, political affiliation aided implementation, where members of the same political group motivated each other:

“I am supporter of the winning politician. He comes to monitor and says everything is good in my school. It motivates me to do the work. But to a non-supporter he always tries to find mistakes in his work. This can develop a negative attitude.” -man, school headmaster, Siraha

Women rarely mentioned politics as a challenge or source of support. No women in non-government roles mentioned politics as a challenge. Our sample included only three women in elected government positions women in politics, and only one elected woman described political challenges when interacting with men. However, the same woman reported that politics did not influence her interactions with women:

“The women are continuous supporting me. They do not have any concern with the political party. The men of opposite party are somehow angry with me. When I ask anything of them, like ‘Brother, please help me in this,’ they say ‘You do in your time. We will do in our time when we win.’” -woman, elected official

Successes in achieving implementation and intervention outcomes

The following section describes men’s and women’s perceived successes at achieving implementation outcomes (i.e., acceptability, appropriateness, penetration, adoption, and sustainability) and intervention outcomes, as defined by Proctor et al. and outlined in Table 1. Implementation outcomes for feasibility, fidelity, and cost were not described by participants during interviews. We also describe how these perceived successes were driven by the implementation approaches men and women used, challenges encountered using those approaches, and the support received to mitigate those challenges, as shown in Figure 1.

Acceptability

Implemented perceived that relational approaches more commonly used by women faced less resistance from the community. Women reported that their “convincing” style of messaging was more likely to be given with respect, asking that households please change rather than demanding change:

“Women speak very humbly. They do not use any harsh word or speak tightly… If we have pressurized the people saying, ‘Uncle!! You have to do it.’ Then maybe they have not built the toilet. But when we respect with respective words, then they agree. This respect develops a good relation with us, and people get convinced easily.” -woman, development organization implementer

In contrast, men using pressure approaches reported being “cursed” or “abused” by some members of the community. One woman attributed the difference in communication styles between men and women to social norms dictating that women give respect to men and household elders:

“Women have habit of giving respect. After marriage they have to respect the mother- and father-in-law. Women have the habit of speaking calmly, humbly. If they speak harshly, it will be hard to change people. But from birth women and girls are reared in that manner that they have to speak humbly and respect the older ones.” -woman, development organization implementer

Appropriateness

FCHVs and women’s and mother’s groups were recruited from local communities and were familiar with local WaSH norms and conditions. While not required to be hired from local communities, all the women working for development organization that we interviewed lived locally in the communities in which they worked. Because of their local ties, women reported that they well positioned to identify community needs and develop appropriate solutions. Women believed that they were more honest in identifying and addressing community needs with good intentions of improving program quality and community health, whereas men, particularly government implementers, were often perceived as acting for political gain:

“In my view, the women understand [community needs] better. Because if men go, they behave like the [political] party workers. Some behave like officers, but the women think that because we are living here, our place should be clean. Many women understand the needs of the community better. Some people’s works are biased with their political party. What the party says or where the voters are high, they work there. But the women live here. They have to live all day and night here. They know better what is needed. Women are honest for themselves, their husband and children.” -woman, development organization local implementer

Men working for development organizations commonly worked in larger geographic areas or in communities where they did not live. Formative research and engagement with women’s, mothers’ and other local groups were some of the strategies used by men to overcome lack of local knowledge and to improve the appropriateness of their implementation approaches.

Penetration

Women’s and mothers’ groups included large proportions of the local population. Women reported using these groups to efficiently spread messages through the community, while men reported challenges with reaching all the households in their working area. Men and women participants also reported that women were the best population to spread WaSH messages, as WaSH duties within the home are traditionally assigned to women, and women were often home during the day to receive messages:

“The message spreads fast through the women. In the home, the women are sanitation workers. Men do not do, how much you convince or fight with men, they do not do the sanitation work… That’s why I thought how I clean my household, I will mobilize the women for the cleaning the village.” -woman, local government representative

Adoption

Approaches that asked households to build a toilet simply to meet government targets were widely perceived by all study participants to be unsuccessful at prompting adoption of sanitation improvements. Poor success of this messaging led participants to try new approaches, including both pressure and convincing approaches. Of the approaches tried in response, both men and women perceived that their efforts led to improvement in adoption of toilets and other WaSH behaviors among the community.

Both men and women also perceived buy-in from community women as important for widespread adoption of WaSH, and that adoption of WaSH practices was faster and more widespread when women actively participated in implementation. One woman attributed this to ease of working with other women and women’s shared understanding and experience of WaSH needs. She perceived that this shared experience and understanding promoted cooperation and collective action by women:

“It is very easy to work through women, because all the work [related to WaSH] is done by the women. That’s why if we can make the women understand about the sanitation, change comes very fast. If the women wills, then the program is completed fast … In my ward, I have achieved success in less time working with the women of the ward. What I have experienced in life, almost all women are also affected by those problems.” — woman, elected official and former development organization implementer

Sustainability

Women-led activities were perceived by both men and women to be more sustainable, and four participants identified women’s leadership specifically as a solution to improve sustainability:

“In the women-led areas, the activities are still continued. When we have gone for follow up, we observed that they are doing follow up of their activities. If you go and monitor, you will find that they are continuing. And the area where there was pressure, or where we had to push for work.… In some places we have seen that people are going back.” -man, development organization implementer

Participants proposed several reasons for the sustainability of women-led programs. Women’s and mothers’ groups were not formal organizations within government or development organizations, so their activities had been sustained through government restructuring and program closeouts. Continual presence of women allowed for sustained delivery of program activities which reinforced habits in the community. Two women reported raising funds in the community to support continuing activities after formal program funding ended.

Implemented perceived that convincing approaches used by women to genuinely change social norms and attitudes regarding WaSH practices. Pressure approaches used by men were perceived as less sustainable: households would construct toilets to avoid sanctions, but individuals had not meaningfully changed perceptions, norms, and behaviors surrounding open defecation. One development organization implementer described how households had built toilets only to receive a “sanitation card” that entitled them to government services but continued openly defecating.

Intervention outcomes

We found no meaningful differences between men and women for intervention outcomes in terms of perceived impact on health or community cleanliness. Both men and women perceived that their efforts and those of others resulted in cleaner communities (e.g., less visible feces, solid waste) and improved health, specifically reducing diarrheal disease and child deaths. Most participants attributed changes to the program overall, noting the importance of a collective movement towards sanitation rather than specific activities or actions by individuals.

Other outcomes—women’s empowerment

Traditional gender norms in Nepal dictate that women should not participate in formal employment outside the home. However, women consistently reported that participating in WaSH programs gave them access to non-domestic employment opportunities, education and training, larger social networks, and power and status in society. Opportunities to access training, build skills, and gain status outside the home were significant motivators to work in WaSH programs, despite not being paid:

“Why I involved with FCHV was because the women are generally limited in the home, and this job have took me out from the house. That’s why I always chose FCHV in first priority. It was my first opportunity.” -FCHV

WaSH work built women’s confidence to voice their opinions in the community and work in other programs and sectors. They reported happiness and pride that their work improved the community and that they had been recognized and praised locally and, in some cases, nationally and internationally, for their work. One woman described her experience being featured in a video campaign:

“I have been recognized in many places, sir …many VDCs [village development committees] of the west, because in that area the program was implemented. The sisters and friends from that area have recognized me easily. When they have recognized, it developed a type of excitement in me, I can also do something. I was afraid of the video earlier. I was not able to speak publicly. After the video, I thought that I can speak more confidently in future.” -FCHV

Participation in WaSH programs encouraged women to participate in social development and employment in non-WaSH areas. After their experience working on WaSH programs, two women in our sample ran for local office, and one woman started a bio-sand filter business and planned to offer training to other women on how to construct the filters. Two program coordinators reported increases in women’s participation in other social programs, such as anti-child marriage, following their engagement in WaSH campaigns. One woman described how participation in the local WaSH program led to changes in how women expressed their views more openly:

“Due to the participation, women started going to the meetings and came outside. The women’s participation was increased in every program. If any NGO comes, like for the women’s violence, the women now go and take the participation. Previously, women did not want to participate. … Now women support in such programs. If any NGO comes or any other person comes, women give time and put their views openly.” -woman, development organization implementer

Discussion

This study explored differences in implementation approaches, challenges and sources of support for implementation, and successes in achieving program quality outcomes among men versus women in community-based WaSH implementation roles in Nepal. We found that men and women used different approaches for implementation, and each approach leveraged different sources of support within the community and faced unique challenges. In turn, these approaches, challenges, and sources of support influenced perceived program quality, as assessed using self-reported implementation and intervention outcomes (Proctor et al., 2011).

Men who were government implementers applied sanctions-based approaches in response to low adoption, while men in development organizations typically refined activity content to target behavioral determinants. Implementation approaches varied less among women, with women in all roles applying relational approaches to convince households to adopt WaSH practices for community wellbeing rather than aggressively demanding change. Women implementers also mobilized other women in the community to deliver messages in groups for more persuasive power.

Women’s approaches to implementation were influenced by power dynamics within households and communities and patriarchal norms in which men are the primary decision makers. Women reported that they were raised to give respect to others, and these respectful messages had higher acceptance within the community than more confrontational approaches used by some men. Power dynamics within Nepali households where women have reduced autonomy are well documented (Wali et al., 2020). Women’s success with respectful messaging is consistent with literature indicating that confrontational messaging is less effective at changing behaviors than other approaches (Hornik, 2002), and that respect and familiarity with social norms are important for successful program delivery by FCHVs (Mohajer and Singh, 2018). We also found that both men and women perceived WaSH as women’s work and women as more appropriate messengers to discuss domestic WaSH-related information. This suggests that women may have greater influence for decision making in WaSH compared to other areas, though further research to is needed to clarify how gender roles impact WaSH related decision making within the home.

We applied social support theory to examine challenges and sources of support for implementation as informational, tangible, emotional, and companionship. Many frameworks that examine the factors supporting effective implementation have been developed in a healthcare context to examine implementation by medical and allied health professionals (Aarons et al., 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009). They consider the role of the community only in terms of patient needs and do not account for how relationships between implementers and beneficiaries may influence implementation. However, this research suggests that social relationships between implementers and beneficiaries are an important determinant of implementation success, which are lacking from many implementation science frameworks. Future studies may incorporate constructs from social support theory or other frameworks for lay implementation to more holistically evaluate determinants of implementation success.

Relationships between women and the community were an important source of support and a driver of their success in delivering acceptable and appropriate messages. Women typically lived in the communities where they worked and leveraged their social ties to mobilize other women to join WaSH campaigns. In contrast, men worked in more widespread geographic areas, which may reduce their ability to build social ties and mobilize companionship support. The importance of social support and social capital for women to practice WaSH behaviors within the home is well documented (Friedrich et al., 2018; House et al., 2013; Malolo et al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2015). Women are more likely to be engaged in community social networks, and to both provide and seek social support from others (Taylor, 2011; Taylor et al., 2000). Our study indicates that these trends extend to the professional setting and approaches to seeking and providing social support between WaSH implementers.

Some differences in challenges and sources of support between men and women may be more proximally attributable to the implementation roles they hold. This is likely the case for information and tangible support, where differences occur as much within genders as across genders. For example, women in development organizations reported being well integrated into training and feedback systems, while unpaid women did not. Poor integration into systems for feedback and learning are likely experienced by unpaid women not because of their gender directly, but because unpaid roles are less integrated into organizational structures that support program implementation. In contrast, emotional challenges and coping strategies of companionship support were consistently experienced and used across all women, suggesting that implementation role was not an important moderator.

While some differences in informational and tangible challenges and support may be proximally driven by the implementation roles, gender bias remains an important distal cause of women’s underrepresentation in paid and senior positions and decision-making processes. Disproportionate numbers of women in unpaid WaSH implementation roles aligns with evidence of gender bias in hiring, promotion, and compensation of women in Nepal (Adhikary, 2016; Wali et al., 2020) and worldwide (Stamarski and Son Hing, 2015; Weichselbaumer, 2004; Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer, 2005). Women in this study reported that they were expected to be the primary duty-bearer for cooking, cleaning, childcare, and other domestic chores even while holding employment outside the home. Other studies have similarly found that domestic responsibilities impede women’s participation in WaSH work, and that support and willingness to share domestic chores from husbands and in-laws is necessary to give women the time and permission needed to engage in WaSH work outside the home (Leder et al., 2017; Rautanen and Baaniya, 2008).

Some have questioned the sustainability, appropriateness, and ethics of relying heavily on unpaid labor from CHVs for program implementation (Kasteng et al., 2015; WHO et al., 2007) and argued that dependency on unpaid female labor reinforces gender inequality (Panday et al., 2017). The WHO recommends that all trained workers, including CHVs, receive “adequate wages and/or other appropriate and commensurate incentives” to ensure sustainability (WHO et al., 2007). Reliance by development organizations and government on unpaid women not only fosters economic inequality, but also reinforces programmatic structures that treat women differently from their paid counterparts and reduce their opportunities for participation in decision making, training and promotions, and other sources of informational support.

Evidence suggests that while altruism is one motivator for engaging in unpaid community health work, benefits such as opportunities for training and building reputation are also important (Government of Nepal, 2014; Kasteng et al., 2015). In this study, women expected to gain knowledge, skills, and social status through WaSH work. However, as gender equality increases in Nepal, these women may be less willing to engage in unpaid work, as the perceived value of opportunities for skill building and status may decrease.

Consensus on how to design appropriate compensation for CHVs is lacking. Some studies suggest that offering formal wages to CHVs may undermine their credibility if the community views them as working only for personal profit rather than altruistic motives (Vareilles et al., 2017). Some Nepali policy makers perceive that formal wages would decrease FCHVs’ motivations to work and decrease community respect, suggesting alternatives to formal wages such as free healthcare and education (Glenton et al., 2010). However, the assertion that pay will decrease community respect is predicated on the perception that woman holding formal employment is improper, and there is little evidence to suggest that payment would reduce motivation to work. These assumptions reinforce regressive gender norms and may no longer hold as gender equality has increased over the past ten years and continues to do so. FCHV participants in this study indicated that wages would increase their motivation to work, a finding which has been supported by other studies in South Asia (Alam et al., 2012). Ultimately, the design of appropriate compensation packages for FCHVs and other unpaid WaSH implementers is likely context specific and will require further research to understand and balance perceptions of policy makers, community members, and implementers themselves regarding what is appropriate, desirable, and best achieves programmatic goals.

Overall, women had less formal education and experience and fewer opportunities for training and feedback, yet women-led programs were perceived as having higher adoption and sustainability. Women achieved these successes regardless of their level of training or access to supervision and feedback. Sustainability of women-led activities suggests that relational group messaging techniques used by women were more effective at changing underlying behavioral drivers of sanitation behavior. This suggests that technical knowledge and experience may be less important than social skills to persuade peers and mobilize social groups, familiarity with local communities, and ability to navigate and communicate appropriately within social dynamics and structures.

Community-level action and collaboration between women is particularly important in light of evidence that household-level WaSH interventions are insufficient to realize health benefits (Pickering et al., 2019a), and calls for “transformative WaSH” as a more holistic effort to eliminate fecal contamination in the household and broader community environment (Pickering et al., 2019b). Collective efficacy (i.e., a group’s belief in their ability to work together to achieve common goals) is important for community change necessary for transformative WaSH (De Shay et al., 2020; Dickin et al., 2017; Salinger et al., 2020). Group messaging strategies and willingness to support each other during implementation demonstrate collective efficacy among women to improve the health and wellbeing of their communities. This translated into implementation successes such as rapid and far-reaching dissemination of messages among women’s and mothers’ groups and sustained commitment of these groups to deliver WaSH activities even where formally funded programs had ended. In contrast, political rivalries among men demonstrated how a lack of collective efficacy can negatively impact program acceptability and adoption.

This study suggests women’s ability to mobilize companionship support among peers may make them more effective at widespread community transformation than men.

Limitations

We assessed successes and challenges from the perspective of local-level implementers only. Participants’ perceptions of successes and challenges related to community attitudes and norms may not fully reflect the range of perspectives within the community. For example, in working to reach ODF, implementers will spend a disproportionate amount of time interacting with households who are resistant to constructing toilets. This may lead to a skewed perception of acceptance and appropriateness of WaSH activities among the community.

In selecting the study sample, we prioritized recruiting a diverse range of perspectives across government, NGO, and multilateral and civil society organizations. This allowed for identifying differences within genders, as well as between genders. However, as a result, the sample size of sub-groups within genders (e.g., paid versus unpaid women) is small. Where gender is strongly associated with the type of implementation role participants fill, disentangling the influence of gender and other contextual factors is challenging. For example, we found that men were more likely to use sanctions, but men are also more likely to hold political office with the power to enforce sanctions (Thapa, 2019). Our sample did not contain enough women in government to conclude whether sanctions approaches would be used by women if they had political power to enact them.

Further research with more senior program officials at the regional and national levels may help to determine the influence of broader contextual factors versus gender. Additionally, recruiting participants from a narrow range of implementation roles could better identify the range of experiences of men and women within that role and disentangle the influences of gender versus other factors associated with implementation role. Similarly, research recruiting participants of only a single gender could achieve a richer representation from different implementation roles to understand how factors such as level of training, political affiliation, or financial compensation affect performance within genders.

Programmatic implications & recommendations

This study illustrates several opportunities to address gender-related challenges and to better support and leverage the abilities of men and women as rural WaSH implementers. At the household and community level, activities to normalize and build acceptance among family and community members for women in non-domestic employment may reduce emotional challenges experienced by women. Frameworks for gender mainstreaming highlight the need to include men as role models and champions for gender equality (Morgan et al., 2016; Tolhurst et al., 2012). Studies have shown that women are more likely to participate in WaSH leadership positions when they have husbands and parents in-law who encourage their work and share childcare and other domestic duties (Leder et al., 2017; Rautanen and Baaniya, 2008). Various frameworks and guidelines exist that can support programs in identifying opportunities and integrating programming to promote gender equality in WaSH (Cortobius and Kjellen, 2014; Gosling, 2012; Halcrow et al., 2010; Panda, 2007).

At the program management level, deemphasizing technical knowledge and prior WaSH experience as key criteria for hiring and promotion may help improve women’s representation in paid roles without sacrificing the quality of activities. We found that women implementers achieved high adoption and sustainability even where they had received little formal training, and ability to mobilize peer support, not technical skills, was critical to that success. Yet, perceived lack of technical proficiency and skills to perform maintenance and repair tasks are barriers to hiring women in WaSH in Nepal (Bhandari et al., 2005). Systematic reviews have identified a variety of interventions to mitigate gender bias in hiring (Isaac et al., 2009), and further research would help identify which are most appropriate for rural WaSH programs.

This study suggests opportunities to strengthen training and feedback systems for non-development organization implementers, particularly for unpaid women who experience challenges related lack of training and poor integration into feedback systems. Training and feedback systems have been found to increase productivity, motivation, satisfaction among CHVs (Scott et al., 2018; Whidden et al., 2018), which is consistent with women in this study reporting training opportunities as a motivator for work. Women expressed a desire for additional technical training (e.g., making reusable menstrual pads), as well as training to develop leadership skills, overcome stigma, and empower themselves and others in their community to challenge traditional gender roles. This study also suggests opportunities to build men’s communication and social mobilization skills. Training to build facilitation skills among both men and women community-based CLTS implementers has been shown to improve sanitation adoption (Crocker et al., 2016).

In the long-term, programs may ultimately need to plan for the possibility that women’s willingness to work in unpaid roles may decrease as gender equality increases, and to reconsider the ethics, appropriateness, and sustainability of relying on unpaid labor. Unpaid women in this study reported that their motivation to work would increase with a formal salary, and studies of CHVs in other contexts have found that satisfaction with both monetary and non-monetary incentives is important for motivation and retention (Kasteng et al., 2015; Kok et al., 2015). Payment of all trained CHVs aligns with WHO recommendations to ensure sustainability of health programs (WHO et al., 2007) and addresses structural inequalities associated with reliance on women’s unpaid labor (Panday et al., 2017). However, coordination will be needed between government and external funders to ensure that payment systems linked to specific WaSH activities are not disruptive of long-term CHV programs.

Conclusions

Women were more likely to be omitted from high-level planning, face stigma for engaging in work outside the home, and hold unpaid roles that are not well integrated into feedback and troubleshooting systems. Women also had less formal experience, education, and training. Social ties between women were robust sources of companionship and emotional support to mitigate challenges, and opportunities to build job skills, social status, and overcome traditional gender norms were important motivators for women to engage in WaSH work.

Both men and women perceived that women were more effective than men at mobilizing widespread, sustained WaSH improvements, which was attributed to their success using relational approaches and leveraging social ties to deliver acceptable and appropriate messages. Women’s skills for motivating collective action indicate that they can be highly effective WaSH implementers despite lack of technical experience and training, and that women’s active participation is important for achieving transformative community change.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nadira Khajawa, Ratan Budhathoki, and all the staff of the SNV Nepal headquarters in Kathmandu and field offices in Siraha, Saptari, Mahottari, Salyan, and Surkhet for their guidance and support. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the program coordinators who assisted with participant recruitment and the time generously given by study participants. We thank the following individuals who provided feedback on the protocols and/or drafts of this manuscript: Jamie Bartram, Clarissa Brocklehurst, Joshua Gam, Antoinette Kome, and Aaron Salzberg.

Funding

This work was funded by the SNV Netherlands Development Organization as a grant to Emory University. Darcy Anderson is supported by grants from the University of North Carolina Royster Society of Fellows and from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES007018).

The study sponsors had the following roles: staff the Nepali headquarters of the SNV Netherlands Development Organization assisted with selection of study districts; staff from SNV district field offices assisted with participant recruitment. The sponsors had no role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the report; or decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

None

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM, 2011. Advancing a Conceptual Model of Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38, 4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari K, 2012. Sanitation in Nepal: Past, Present and Future. Kunti Bhoomi Memorial Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary JR, 2016. Barriers to career progression: a study of the perceptions of Nepali women employees. Journal of Business and Management Research 1, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Alam K, Tasneem S, Oliveras E, 2012. Performance of female volunteer community health workers in Dhaka urban slums. Soc. Sci. Med 75, 511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari BS, Grant M, Pokharel D, 2005. Sustainable community water: managing supply systems in the mid-hills of Nepal. Water Policy 7, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, Huicho L, 2010. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals: a systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Global health workforce Alliance 1, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso BA, Sevilimedu V, Fung IC-H, Patkar A, Baker KK, 2015. Gender disparities in water, sanitation, and global health. The Lancet 386, 650–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortobius M, Kjellen M, 2014. Gender Practice in Water Governance Programmes: From Design to Results. Stockholm International Water Institute, Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Abodoo E, Asamani D, Domapielle W, Gyapong B, Bartram J, 2016. Impact Evaluation of Training Natural Leaders during a Community-Led Total Sanitation Intervention: A Cluster-Randomized Field Trial in Ghana. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 8867–8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC, 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science : IS 4, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Shay R, Comeau DL, Sclar GD, Routray P, Caruso BA, 2020. Community Perceptions of a Multilevel Sanitation Behavior Change Intervention in Rural Odisha, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water Supply and Sewerage, 2011. National sanitation and hygiene master plan. Government of Nepal, Kathmandu. [Google Scholar]

- Dickin S, Bisung E, Savadogo K, 2017. Sanitation and the commons: The role of collective action in sanitation use. Geoforum 86, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- El Arifeen S, Christou A, Reichenbach L, Osman FA, Azad K, Islam KS, Ahmed F, Perry HB, Peters DH, 2013. Community-based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health-service delivery in Bangladesh. The Lancet 382, 2012–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich MND, Kappler A, Mosler H-J, 2018. Enhancing handwashing frequency and technique of primary caregivers in Harare, Zimbabwe: A cluster-randomized controlled trial using behavioral and microbial outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med 196, 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenton C, Scheel IB, Pradhan S, Lewin S, Hodgins S, Shrestha V, 2010. The female community health volunteer programme in Nepal: Decision makers’ perceptions of volunteerism, payment and other incentives. Soc. Sci. Med 70, 1920–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling L, 2012. Equity and inclusion: A rights-based approach. WaterAid, London. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Nepal, 2014. Female Community Health Volunteer National Survey Report 2014. Government of Nepal, Kathmandu. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JP, Hirai M, Kim SS, 2016. An Analysis of Water Collection Labor among Women and Children in 24 Sub-Saharan African Countries. PLoS One 11, e0155981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcrow G, Rowland C, Willetts J, Crawford J, Carrard N, 2010. Resource Guide: Working effectively with women and men in water, sanitation and hygiene programs. International women’s Development Agency and Institute for Sustainale Futures, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney CA, Israel BA, 2008. Social networks and social support. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice 4, 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque BA, Juncker T, Sack RB, Ali M, Aziz KM, 1996. Sustainability of a water, sanitation and hygiene education project in rural Bangladesh: a 5-year follow-up. Bull. World Health Organ 74, 431–437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R, 2002. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- House S, Mahon T, Cavill S, 2013. Menstrual Hygiene Matters: a resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. Reproductive Health Matters 21, 257–259. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac C, Lee B, Carnes M, 2009. Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: A systematic review. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 84, 1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane S, Kok M, Ormel H, Otiso L, Sidat M, Namakhoma I, Nasir S, Gemechu D, Rashid S, Taegtmeyer M, Theobald S, de Koning K, 2016. Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: A multi-country comparative study. Soc. Sci. Med 164, 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar K, Chambers R, 2008. Handbook on community-led total sanitation (CLTS). London: Plan International (UK) and Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. [Google Scholar]

- Kasteng F, Settumba S, Källander K, Vassall A, Group, t.i.S., 2015. Valuing the work of unpaid community health workers and exploring the incentives to volunteering in rural Africa. Health Policy Plan. 31, 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E, Lee K, Shields KF, Cronk R, Behnke N, Klug T, Bartram J, 2017. The role of social capital and sense of ownership in rural community-managed water systems: Qualitative evidence from Ghana, Kenya, and Zambia. Journal of Rural Studies 56, 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RB, Zyzanski SJ, Alemagno SA, 1991. Prediction of motivation and behavior change following health promotion: Role of health beliefs, social support, and self-efficacy. Soc. Sci. Med 32, 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri RB, Mishra SR, Khanal V, 2017. Female Community Health Volunteers in Community-Based Health Programs of Nepal: Future Perspective. Frontiers in Public Health 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, Broerse JEW, Kane SS, Ormel H, Tijm MM, de Koning KAM, 2015. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 30, 1207–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP, 1997. Social support: a conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs 25, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leder S, Clement F, Karki E, 2017. Reframing women’s empowerment in water security programmes in Western Nepal. Gender & Development 25, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Majorin F, Torondel B, Ka Seen Chan G, Clasen T, 2019. Interventions to improve disposal of child faeces for preventing diarrhoea and soil-transmitted helminth infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malolo R, Kumwenda S, Chidziwisano K, Kambala C, Morse T, 2021. Social outcomes of a community-based water, sanitation and hygiene intervention. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. [Google Scholar]