To the Editor—The overuse of antibiotics is a major public health crisis and results in increased antibiotic resistant organisms,1 adverse drug events,2,3 higher costs, risk for C. difficile infections4, and changes in the microbiome that place patients at risk for chronic diseases.5,6 In the United States, we have >2.8 million antibiotic resistant infections and ~35,000 deaths annually due to highly resistant bacteria.1

The majority of antibiotic use occurs in outpatient settings, and at least 30% of these antibiotics are not needed.7 Thus, programs to reduce outpatient prescribing are critical. In 2016 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published the Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship.8 Tracking and reporting, also known as individualized provider audit and feedback, has been shown to be highly effective approaches to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. Unfortunately, while many of the elements are relatively easy for practices to implement, tracking and reporting has remained a major obstacle.

Since most practices now have electronic health records (EHR), the EHR should be leveraged to improve the efficiency of antibiotic stewardship programs. One challenge to the implementation of EHR-based tracking and reporting is many EHRs do not require antibiotic orders to be linked to an indication or diagnosis. Without knowing the indication, reducing the use of antibiotics for specific diagnoses cannot be tracked by programming alone. This situation is particularly problematic for phone-based prescribing or visits with multiple diagnoses since data would likely require manual abstraction. In our experience requiring providers to link an order with a diagnosis is simple to activate and requires only one additional click by the prescriber. This minor change can dramatically simplify data collection.

Furthermore, antibiotic prescribing feedback reports have to be prepared that are individualized and compare outcomes between providers and practices. Ongoing analyses of data are necessary to assess whether interventions are effective. A recent study of 8 community-based practices found that practices spent up to 20 hours per month preparing reports and nearly all used manual data abstraction.9 Acquiring data electronically was wrought with costs, time delays, and difficulty translating data into reports. Additionally, though many EHR systems have antibiotic stewardship platforms and the ability to create reports, EHR platforms can be time-consuming and expensive to build and modify, and often they are not flexible enough to meet the needs of specific projects. Finally, EHR stewardship tools typically are not able to provide information on which providers have reviewed reports.

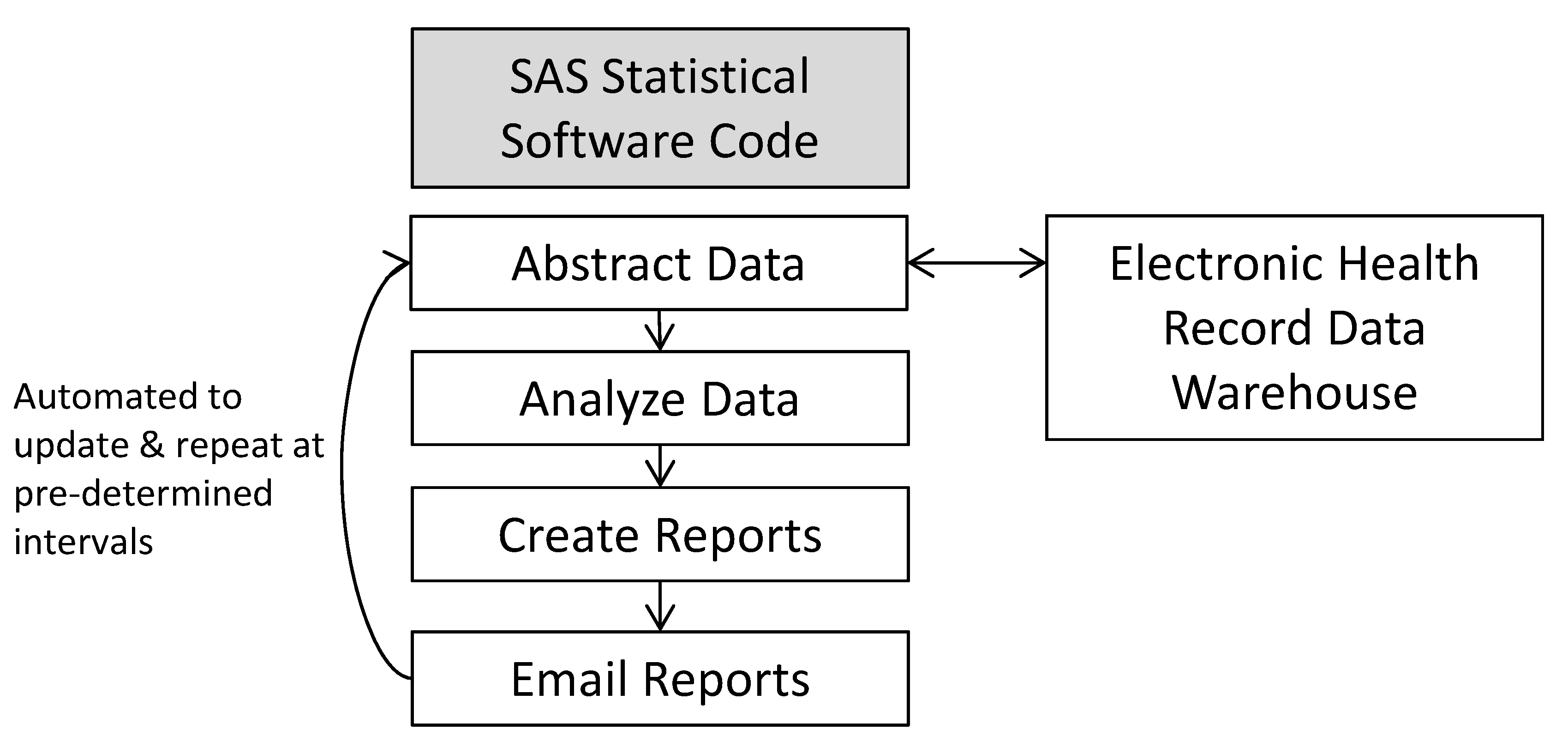

Given these challenges, we developed a system called OASIS (Outpatient Automated Stewardship Information System) to help alleviate some of the barriers to tracking and reporting.10 OASIS© uses common statistical software (SAS, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to electronically abstract data from the EHR data warehouse, analyze, and report the data (Fig. 1). Because it uses common statistical software rather than an EHR platform, it is able to include and exclude subgroups of patients easily (eg, patients with a history of MRSA). OASIS© is flexible, which permits more complex analyses if desired. Nearly any output format can be designed. It is also low-cost to set up and use. Importantly, it can be completely automated to generate and e-mail reports directly to stewards, providers, and administrators at prespecified intervals, thus obviating the need for manual data abstraction, development of feedback reports, and dissemination of the reports. Providers can review data on their mobile devices if desired and “read” receipts can be used to track who has read reports.

Fig. 1.

The OASIS© method for automating the creation of individualized provider antibiotic prescribing reports with peer comparison.

Importantly, because major EHRs store data in warehouses using standard formats and tables, the statistical code can be freely shared between organizations and utilized with only minor modifications. As an example, if stewards want to implement an intervention across many organizations to reduce antibiotic prescribing for bronchitis they can simply share the code with each organization.

We recently used OASIS© as part of a bundled stewardship intervention to reduce unnecessarily long durations of antibiotics for uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) at Denver Health in Denver, Colorado (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Uncomplicated AOM is a complex target from an EHR perspective because it includes multiple diagnostic codes, it requires exclusion of patients with complicated infections, and it requires obtaining duration of therapy from prescriptions for antibiotic suspensions. Because the reports were automated, our time to review monthly data was only a few minutes. The reports included clinic- and provider-level prescribing data in a bar graph format that included baseline prescribing from the prior year, year-to-date prescribing, and prescribing in the prior month. Provider names were included on reports to provide direct peer comparison. The bundled intervention, of which OASIS©-generated reports were a major component, reduced unnecessarily long durations of antibiotics for uncomplicated AOM by 76% in 6 months. We expect that minimal data analyst time would be needed to modify the code to mimic the project at another organization.

Given the simplicity and flexibility of this approach, we encourage other organizations to utilize this method. The small amount of time and small financial investment at the beginning of the intervention was overwhelmingly justified by the reduced time and cost over the life of the project. We plan to collaborate with the University of Rochester to make minor modifications to the EHR to link antibiotic orders to a diagnosis and to set up OASIS© for their antibiotic stewardship needs. In conclusion, OASIS© is a potentially important tool for streamlining tracking and reporting. Organizations should consider adopting OASIS© as a means to improve efficiency of outpatient antibiotic stewardship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support. Support for OASIS© was provided by the Denver Health Office of Research Pilot Grant Program. H.F. received salary support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (grant no. K23HD099925). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary material. To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1409

Conflicts of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Note. OASIS© may be licensed at no cost by completing a web-based license or by contacting the lead author (Holly Frost) or coauthors.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995;274:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohsen S, Dickinson JA, Somayaji R. Update on the adverse effects of antimicrobial therapies in community practice. Medecin de Famille Canadien 2020;66:651–659. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KA, Khanafer N, Daneman N, Fisman DN. Meta-analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013;57:2326–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad OF, Akbar A. Microbiome, antibiotics and irritable bowel syndrome. Br Med Bull 2016;120:91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton DB, Scott FI, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case-control study. Pediatrics 2015;136:e333–e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA 2016;315:1864–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost HM, Andersen LM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Norlin C, Czaja CA. Sustaining outpatient antimicrobial stewardship: do we need to think further outside the box? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020;41:382–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost HM, Lou Y, Munsiff S. OASIS (Outpatient Automated Stewardship Information System). IDWeek IDEA Incubator conference held virtually; October 2020. OASIS Wins Grand Prize at IDea Incubator Competition Held in Collaboration with Johnson & Johnson Innovation – JLABS. https://www.idsociety.org/news-publications-new/articles/2020/oasis-wins-grand-prize-at-idea-incubator-competition-held-in-collaboration-with-johnson-johnson-innovation-jlabs/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.