Abstract

Background

It has been reported that longer time intervals from stroke onset to endovascular therapy are associated with lower rates of successful reperfusion in acute ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion. However, procedural variables and potential mechanisms of this association have not been fully elucidated.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of individual patient data from the North American Solitaire Stent Retriever Acute Stroke and Trevo Stent-Retriever Acute Stroke registries. We included patients with internal carotid and middle cerebral artery occlusion (M1/M2) who were treated by mechanical thrombectomy within 24 hours of last known normal. The primary outcome was reperfusion, defined as a Thrombolysis In Cerebral Infraction score of ≥2b. The secondary outcome was reperfusion on the first pass. The primary predictor was duration of symptomatic stroke, defined as time from last known normal to time of final pass. Adjusted logistic regression models were utilized to determine associations between variables and outcome.

Results

We included 506 patients, of which 401 (79.3%) achieved successful reperfusion (TICI 2b/3). The mean (SD) duration of symptomatic stroke was 6.8 (3.5) hours and in the adjusted logistic regression model the duration of symptomatic stroke was associated with reperfusion (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84–0.96) and reperfusion on the first pass (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.83–0.95). In that model, the predicted probability of reperfusion was 88% (95% CI, 0.83–0.92) at 1 hour, 81% (0.78–0.84) at 6 hours, 70% (0.63–0.77) at 12 hours, and 42% (0.17–0.67) at 24 hours (ptrend=0.001). Reperfused patients were significantly younger, more likely to be male, and to have had a balloon guide catheter used during the procedure.

Conclusion

In a real-world cohort of acute ischemic stroke patients with anterior circulation occlusion treated with endovascular therapy, longer duration of symptomatic stroke is associated with lower rates of successful reperfusion and reperfusion on the first pass.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, large vessel occlusion, endovascular thrombectomy, neurologic outcome

Introduction

In major clinical trials of patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) due to large vessel occlusion (LVO), the rate of successful reperfusion after endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) varies considerably.[1–10] While reperfusion is impacted by several nonmodifiable factors like clot characteristics, occlusion site, or collateral status, there are some modifiable factors that can be targeted to improve outcomes in patients with LVO.[11–14] Among potentially modifiable factors, time to recanalization has been the target of scrutiny given the ability to affect clinical outcomes with potential modifications at both the systems of care and provider levels.[14–16]

Prior AIS research on patients with LVOs suggests that a longer time interval from stroke onset to endovascular therapy is associated with lower rates of successful reperfusion.[12,13,15] However, these studies were not able to fully explore procedural variables and potential mechanisms of this association. This investigation examines two large registries of patients with LVO treated with EVT using second generation stent retrievers to determine the impact of clot dwell time (DSS) on the success of EVT and possible procedural variables associated with improved outcomes.

Methods

This is a patient-level secondary analysis of the North American Solitaire Stent Retriever Acute Stroke (NASA) and Trevo Stent-Retriever Acute Stroke (TRACK) registries combined into a single cohort. The de-identified dataset was not subject to institutional review board approval. Both registries were independent investigator initiated studies that prospectively enrolled consecutive EVT-treated AIS patents with confirmed LVO who had the Solitaire or Trevo stent retriever as the first line strategy.[17–19] We included AIS patients with occlusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) or middle cerebral artery (MCA) M1-2 segments and arterial access for EVT obtained within 24 hours of last known normal. The primary outcome was reperfusion, defined as a modified Thrombolysis In Cerebral Infarction (TICI) score of ≥2b.[20,21] The TICI scores in both registries were centrally adjudicated at the coordinating center.[19] The secondary outcome was first pass effect (FPE), defined as reperfusion on the first pass of EVT.[22] The primary predictor was duration of symptomatic stroke (DSS), defined as hours from last known well to the final pass. Although other analyses have used the time from stroke onset or last known well to groin puncture, we chose time from last known well to final pass as our predictor because it more accurately reflects the cumulative dwell time of the clot until the procedural success or failure.

Subject characteristics are summarized by the full cohort and stratified by reperfusion. Categorical data are presented as proportions, normally distributed continuous data as mean with standard deviation, and nonnormally distributed continuous data as median with interquartile range. We tested for intergroup differences with Student’s t-test for continuous variables, the chi-squared test for categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for ordinal variables. We fit logistic regression models to our outcomes, both unadjusted and adjusted. The multivariate models included an a priori model which was adjusted for patient age, sex, race, baseline systolic blood pressure, NIH stroke scale, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), site of occlusion (ICA, M1, and M2), number of EVT passes, guide catheter type, intravenous alteplase, and intraarterial alteplase. We also created a second model adjusted for covariates selected with least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) methodology.[23] Models fit to the secondary outcome of FPE had identical adjustments with the exception of excluding the number of passes.

After logistic regression, we calculated the adjusted predicted probabilities of our outcomes using marginal effects. We used ordinal logistic regression for the tertiary outcome (number of passes). To limit multicollinearity, we ensured models had a variance inflation factor less than 10. We further stratified the cohort by informative binary variables and performed our analyses separately in the resulting subgroups. After logistic regression we computed the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) for our models. We performed two sensitivity analyses. In the first we defined our time variable as time from last known normal to time of groin puncture. In the second, we excluded 114 patients who received rescue therapy, which included intracranial stenting or angioplasty, because that could have influenced the rate of reperfusion. Stata software (v16.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all analysis.

Results

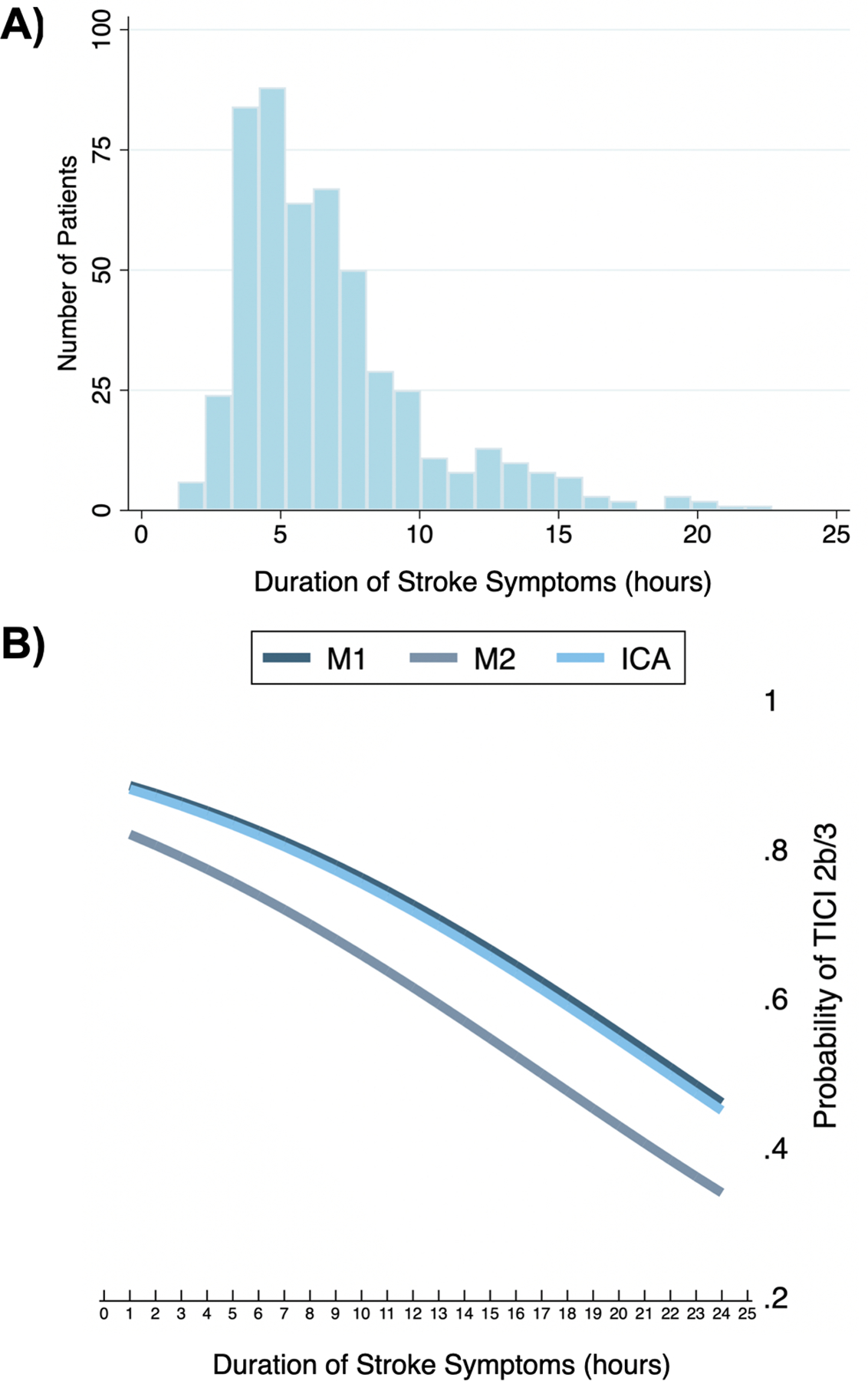

We included 506 patients, of which 426 (84.2%) came from the TRACK registry and 80 (15.8%) from NASA. The site of occlusion was the ICA in 137 (27.1%), MCA M1 in 277 (54.7%), and MCA M2 in 92 (18.2%). The mean (SD) age was 66.7 (14.6) years, 250 (49.4%) were male, and 278 (54.9%) received intravenous alteplase. The mean (SD) DSS was 6.8 (3.5) hours with a normal distribution that had an expected positive skew (Figure 1A). Reperfusion was achieved in 401 (79.3%) patients and FPE in 201 (39.7%). The mean (SD) number of passes in reperfused patients was 1.9 (1.1) versus 2.5 (1.4) in non-reperfused patients (p<0.001). Reperfused patients were significantly younger, more likely to be male, have a balloon guide catheter used during the procedure, and less likely to require rescue therapy (Table 1).

Figure 1.

A) Histogram of clot dwell times, B) Predicted probability* of reperfusion for the middle cerebral artery (MCA) segments and internal carotid artery (ICA).

*Adjusted for patient age, sex, race, baseline systolic blood pressure, NIH stroke scale, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), site of occlusion, number of passes, balloon guide catheter, clot aspiration, rescue treatment, intravenous alteplase, and intraarterial alteplase.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and procedural variables for the full cohort and stratified by reperfusion status.

| Variable | Full cohort (n=506) | Reperfused (n=401) | Not reperfused (n=105) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66.7 (14.6) | 66.0 (15.0) | 69.7 (12.5) | 0.018 |

| Male sex | 346, 48.9% | 281, 51.1% | 65, 41.1% | 0.027 |

| White race | 350, 69.2% | 269, 67.1% | 81, 77.1% | 0.047 |

| Hypertension (n=505) | 379, 75.1% | 298, 74.5% | 81, 77.1% | 0.578 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 206, 40.7% | 156, 38.9% | 50, 47.6% | 0.106 |

| Diabetes | 124, 24.5% | 97, 24.2% | 27, 25.7% | 0.746 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 249, 49.2% | 197, 49.1% | 52, 49.5% | 0.942 |

| Smoker | 120, 23.7% | 95, 23.7% | 25, 23.8% | 0.980 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure | 144.0 (25.9) | 143.9 (25.5) | 144.5 (27.5) | 0.845 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure | 77.1 (18.8) | 77.0 (18.3) | 77.6 (20.5) | 0.808 |

| NIH stroke scale | 17, 13–22 | 17, 13–21 | 17, 14–22 | 0.390 |

| Occlusion site | ||||

| General anesthesia (n=498) | 306, 61.5% | 238, 60.6% | 68, 64.8% | 0.432 |

| Intravenous alteplase | 278, 54.9% | 218, 54.4% | 60, 57.1% | 0.610 |

| Intraarterial alteplase | 128, 25.3% | 93, 23.2% | 35, 33.3% | 0.033 |

| Trevo device (vs. Solitaire) | 426, 84.2% | 338, 84.3% | 88, 83.8% | 0.905 |

| Balloon guide catheter | 366, 51.7% | 296, 53.8% | 70, 44.3% | 0.035 |

| Contact aspiration | 116, 22.9% | 89, 22.2% | 27, 25.1% | 0.445 |

| Number of passes | 2.0 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Rescue treatment | 114, 22.5% | 72, 18.0% | 42, 40.0% | <0.001 |

Binary variables presented as n, % and intergroup differences tested with the chi-squared test; continuous variables presented as mean (standard deviation) and tested with Student’s t-test; ordinal variables presented as median, interquartile range and tested with Wilcoxon Ranksum test.

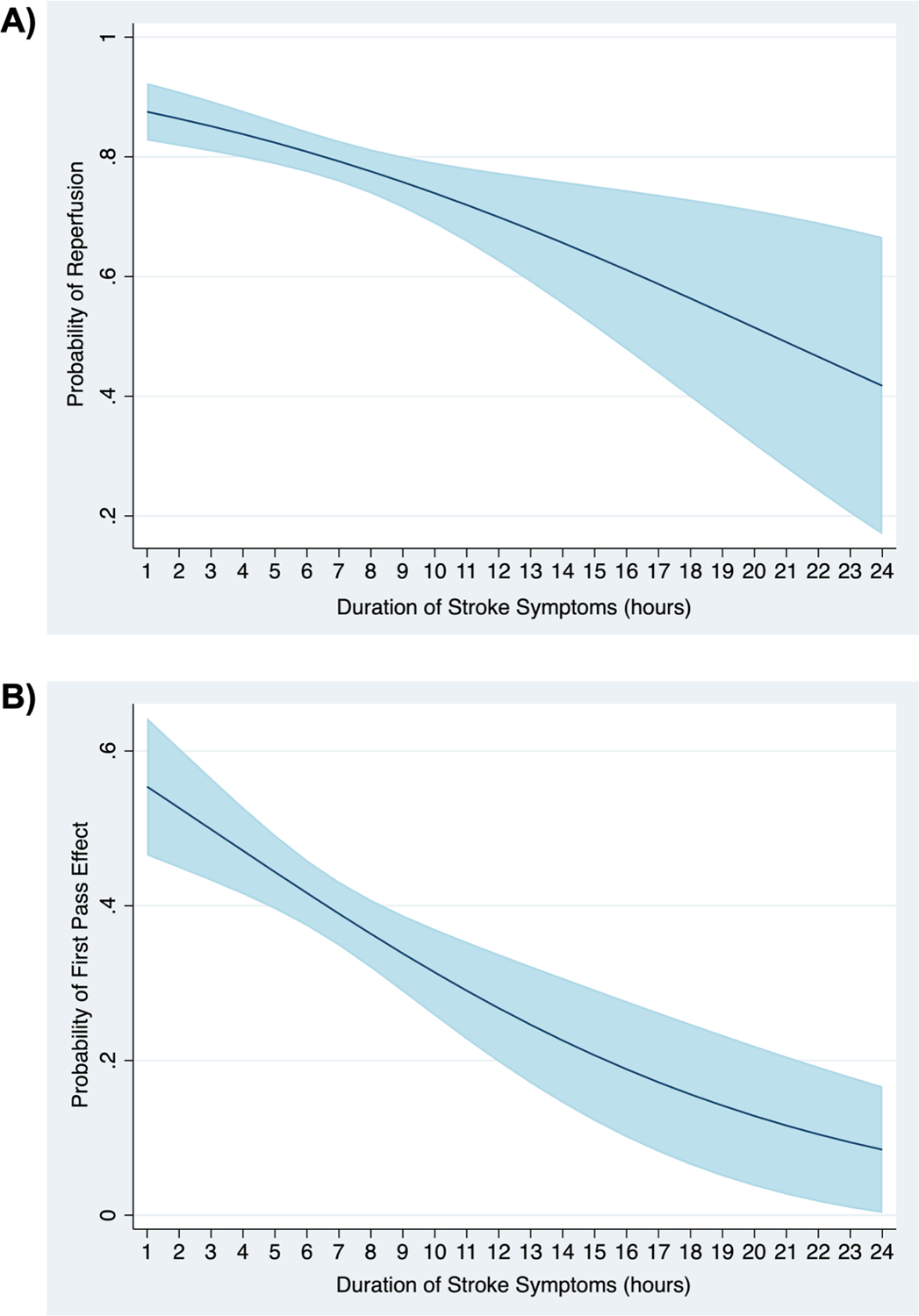

In unadjusted analysis, DSS was associated with reperfusion (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.97, p=0.003). In the multivariate model adjusted for a priori covariates (Table 2), DSS remained associated with reperfusion (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84–0.96, p=0.001). The AUCs for those models were 0.59 and 0.73, respectively. The predicted probability of reperfusion in this model was 88% (95% CI, 0.83–0.92) at 1 hour, 81% (0.78–0.84) at 6 hours, 70% (0.63–0.77) at 12 hours, and 42% (0.17–0.67) at 24 hours (ptrend=0.001) (Figure 2). In the multivariate model with covariates chosen with LASSO, we found a continued association between DSS and reperfusion (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.98, p=0.012) with an AUC of 0.74.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models fit to reperfusion, showing odds ratios for a one hour change in duration of stroke symptoms.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1* | 0.92 | 0.87–0.97 | 0.003 |

| Model 2† | 0.90 | 0.84–0.96 | 0.001 |

| Model 3‡ | 0.92 | 0.87–0.98 | 0.012 |

Model 1 unadjusted.

Model 2 adjusted for patient age, sex, race, baseline systolic blood pressure, NIH stroke scale, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), site of occlusion, number of passes, balloon guide catheter, clot aspiration, rescue treatment, intravenous alteplase, and intraarterial alteplase.

Model 3 adjusted for patient age, sex, atrial fibrillation, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), balloon guide catheter, and rescue treatment.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability* of A) reperfusion and B) first pass effect with 95% confidence interval.

*Adjusted for patient age, sex, race, baseline systolic blood pressure, NIH stroke scale, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), site of occlusion, number of passes (model fit to reperfusion only), balloon guide catheter, clot aspiration, rescue treatment, intravenous alteplase, and intraarterial alteplase.

The rates of reperfusion were 79.6%, 80.1%, and 76.1% for the ICA, MCA M1, and M2. The mean number of passes was 2.1, 2.1, and 1.6 for the ICA, MCA M1, and M2. All three demonstrated a relationship to DSS (Figure 1B). In Table 3, the stratifications are shown for binary variables that were significantly different between reperfused and non-reperfused patients as seen in Table 1. The interaction terms between these variables and DSS were not significant (p>0.05), but the stratifications are hypothesis generating. In patients with MCA occlusion (n=369), the DSS remained associated with reperfusion (OR 0.91, 0.85–0.98, p=0.016), but not in ICA occlusion (n=137, p=0.119). In patients treated with conventional or direct access guide catheters (n=242), the DSS remained associated with reperfusion (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.75–0.92, p=0.001), but not in those treated with balloon guide catheters (n=264, p=0.362). The percentage of patients with reperfusion was higher in those treated with balloon guide catheters (83.7% vs. 74.4%, p=0.010).

Table 3.

Logistic regression models fit to reperfusion, showing odds ratios for a one hour change in duration of stroke symptoms in stratified subgroups.

| Variable | Odds ratio* | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient sex | |||

| Male (n=250) | 0.87 | 0.76–0.99 | 0.029 |

| Female (n=256) | 0.90 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.016 |

| Occlusion site | |||

| Middle cerebral artery (n=369) | 0.91 | 0.85–0.98 | 0.016 |

| Internal carotid artery (n=137) | 0.84 | 0.68–1.05 | 0.119 |

| Guide catheter | |||

| Balloon guide (n=264) | 0.95 | 0.86–1.06 | 0.362 |

| Conventional/Distal access (n=242) | 0.83 | 0.75–0.92 | 0.001 |

Adjusted for patient age, sex, race, baseline systolic blood pressure, NIH stroke scale, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), site of occlusion, number of passes, balloon guide catheter, clot aspiration, rescue treatment, intravenous alteplase, and intraarterial alteplase.

In the first sensitivity analysis, where we calculated DSS as the time from last known normal to groin puncture, DSS remained associated with reperfusion in the a priori adjusted model (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.99–1.00 p=0.026). In the second sensitivity analysis, where we excluded 114 patients who received rescue therapy, DSS remained associated with reperfusion in the a priori adjusted model (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.96, p=0.005).

Discussion

In the present analysis, DSS was associated with the likelihood of reperfusion and FPE in AIS patients with anterior circulation LVO treated with stent retriever EVT. Unlike prior analyses, we were able to demonstrate this finding in a cohort with detailed procedural data that we adjusted for in multivariate models. For years it has been known that LVO is an emergency and shorter intervals between onset of occlusion and reperfusion are associated with superior outcomes.[12,13,15,24] Previous analysis of the time elapsed between occlusion and treatment focused on arterial access times, which has historically been instrumental in determination of treatment candidacy.[12,13,15] Since it is, in fact, the cumulative duration of vessel occlusion that physiologically impacts the clot and the tissue downstream from the LVO, we defined DSS as the time from last known normal to final pass rather than arterial access time, although our findings held true when using arterial access time for the DSS measurement.

These real-world results are in contrast to data from randomized clinical trials in this patient population. For example, in the MR CLEAN trial, which enrolled LVO patients < 6 hours from onset, the rate of TICI 2b/3 reperfusion in the EVT cohort was 58.7% and in the HERMES meta-analysis of early window trials it was 71%, while in DEFUSE 3, which enrolled LVO patients 6–16 hours from onset, the rate of reperfusion in the EVT cohort was higher at 75.8%.[2,10,25] In DAWN, an additional late window trial, the rate of recanalization was similar at 77% of the EVT-treated patients.[9] The more selective inclusion criteria of DEFUSE 3 and DAWN, which favored patients with good collateral circulation who are more likely to be reperfused,[26] may have led to this discrepancy. An analysis of LVO patients presenting in the late window to a large comprehensive stroke center identified that only 21.3% and 10.4% would have qualified for EVT by DEFUSE 3 or DAWN criteria, respectively.[27] This illustrates the challenges of generating widely generalizable data from clinical trials, and the importance of real-world analyses.

Our results suggest that time-dependent characteristics of LVO clots may be dynamic and render thrombus less amenable to EVT as time progresses.[28] Prior histopathologic analyses of EVT-retrieved clot fragments have shown that patients who fail to achieve reperfusion are more likely to have fibrin-rich clots.[29,30] The dense, highly branched network of a fibrin-rich clot is the final step in clot formation, which is time dependent.[31] Another important element of clot consolidation is the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) adjacent to the clot. Recent research has shown that over time clots induce the formation of NETs, rendering patients less likely to achieve reperfusion.[32,33] Further study is needed to explore the histopathologic composition of LVO clots, which may lead to adjunctive reperfusion therapeutics.

Alternatively, it could be that clots that are more amenable to lysis result in reperfusion before EVT can be performed, whereas more resistant clots persist deeper into the DSS window and can reduce rates of reperfusion from EVT. The current analysis provides several insights into the impact of additional factors that may affect reperfusion, some of which are determined by the provider performing EVT. Use of a balloon guide catheter was associated with better rates of reperfusion and FPE, confirming recent findings of the benefits of using these devices in EVT.[34–37] Reperfusion was less likely to occur in cases requiring rescue therapy in the form of intracranial angioplasty or stent deployment. While this does not imply that rescue therapy should not be performed, as reperfusion was achieved in 63.2% (72/114) in this subgroup, knowledge of this may be helpful for interventionalists’ decision-making process.

Several important limitations warrant discussion. Prospective registries can introduce limitations and inherent bias, including selection and ascertainment biases. In addition to not following stringent inclusion criteria, nonstandard protocols are also utilized that vary among centers and practitioners. We also do not know which patients had wakeup stroke or unwitnessed stroke onset, both of which may artificially prolong the duration of stroke symptoms. The strengths of this analysis are that it reflects real-world clinical scenarios and provides evidence of high rates of reperfusion in all targeted ICA and MCA segments with comparable findings between devices.

Conclusion

In a real-world cohort of acute ischemic stroke patients with anterior circulation occlusion treated with endovascular therapy, longer clot dwell time is associated with lower rates of successful reperfusion and first pass effect.

Table 4.

Logistic regression models fit to first pass effect, showing odds ratios for a one hour change in duration of stroke symptoms.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1* | 0.93 | 0.88–0.98 | 0.012 |

| Model 2† | 0.89 | 0.83–0.95 | <0.001 |

| Model 3‡ | 0.93 | 0.88–0.99 | 0.017 |

Model 1 unadjusted.

Model 2 adjusted for patient age, sex, race, baseline systolic blood pressure, NIH stroke scale, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), site of occlusion, balloon guide catheter, clot aspiration, rescue treatment, intravenous alteplase, and intraarterial alteplase.

Model 3 adjusted for patient age, sex, atrial fibrillation, device (Solitaire vs. Trevo), balloon guide catheter, and rescue treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the NASA and TRACK investigators, as well as Kristine Below for assistance with the editing of the manuscript.

Funding

Dr. de Havenon is supported by NIH-NINDS K23NS105924. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

AD reports investigator initiated funding from AMAG and Regeneron pharmaceuticals. RGN reports consulting fees for advisory roles with Anaconda, Biogen, Cerenovus, Genentech, Imperative Care, Medtronic, Phenox, Prolong Pharmaceuticals, Stryker Neurovascular and stock options for advisory roles with Astrocyte, Brainomix, Cerebrotech, Ceretrieve, Corindus Vascular Robotics, Vesalio, Viz-AI, and Perfuze. TN is Principal Investigator of the CLEAR study funded by Medtronic; serves on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for TESLA (Thrombectomy for Emergent Salvage of Large Anterior Circulation Ischemic Stroke), ENDOLOW (Endovascular Therapy for Low NIHSS Ishemic Strokes), SELECT 2 (A Randomized Controlled Trial to Optimize Patient’s Selection for Endovascular Treatment in Acute Ischemic Stroke) trials.

References

- 1.Boyle K, Joundi R, Aviv R. An historical and contemporary review of endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Neurovascular Imaging 2017;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PSS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular Therapy for Ischemic Stroke with Perfusion-Imaging Selection 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1019–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 Hours after Symptom Onset in Ischemic Stroke 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780. 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Stent-Retriever Thrombectomy after Intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA Alone in Stroke 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061. 2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1415061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bracard S, Ducrocq X, Mas JL, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy after intravenous alteplase versus alteplase alone after stroke (THRACE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:1138–47. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30177-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muir KW, Ford GA, Messow C-M, et al. Endovascular therapy for acute ischaemic stroke: the Pragmatic Ischaemic Stroke Thrombectomy Evaluation (PISTE) randomised, controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:38–44. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 Hours after Stroke with a Mismatch between Deficit and Infarct. N Engl J Med 2018;378:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. Thrombectomy for Stroke at 6 to 16 Hours with Selection by Perfusion Imaging. N Engl J Med 2018;378:708–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning NW, Chapot R, Meyers PM. Endovascular Stroke Management: Key Elements of Success. CED 2016;42:170–7. doi: 10.1159/000445449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourcier R, Goyal M, Liebeskind DS, et al. Association of Time From Stroke Onset to Groin Puncture With Quality of Reperfusion After Mechanical Thrombectomy: A Meta-analysis of Individual Patient Data From 7 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:405–11. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal M, Almekhlafi MA, Fan L, et al. Evaluation of interval times from onset to reperfusion in patients undergoing endovascular therapy in the Interventional Management of Stroke III trial. Circulation 2014;130:265–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo AJ, Andersson T. Thrombectomy in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Challenges to Procedural Success. J Stroke 2017;19:121–30. doi: 10.5853/jos.2017.00752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Settecase F, McCoy DB, Darflinger R, et al. Improving mechanical thrombectomy time metrics in the angiography suite: Stroke cart, parallel workflows, and conscious sedation. Interv Neuroradiol 2018;24:168–77. doi: 10.1177/1591019917742326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southerland AM, Johnston KC, Molina CA, et al. Suspected Large Vessel Occlusion - Should EMS transport to the nearest PSC or bypass to a CSC with Endovascular Capabilities? Stroke 2016;47:1965–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaidat OO, Castonguay AC, Gupta R, et al. North American Solitaire Stent Retriever Acute Stroke registry: post-marketing revascularization and clinical outcome results. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery 2014;6:584–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidat OO, Castonguay AC, Nogueira RG, et al. TREVO stent-retriever mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke secondary to large vessel occlusion registry. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery 2018;10:516–24. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokin M, Abou-Chebl A, Castonguay AC, et al. Real-world stent retriever thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke beyond 6 hours of onset: analysis of the NASA and TRACK registries. J Neurointerv Surg 2019;11:334–7. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warach Steven J., Luby Marie, Albers Gregory W., et al. Acute Stroke Imaging Research Roadmap III Imaging Selection and Outcomes in Acute Stroke Reperfusion Clinical Trials. Stroke 2016;47:1389–98. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, et al. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2003;34:e109–137. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000082721.62796.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaidat OO, Castonguay AC, Linfante I, et al. First Pass Effect: A New Measure for Stroke Thrombectomy Devices. Stroke 2018;49:660–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribbing J, Nyberg J, Caster O, et al. The lasso—a novel method for predictive covariate model building in nonlinear mixed effects models. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2007;34:485–517. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9057-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heit JJ, Mlynash M, Christensen S, et al. What predicts poor outcome after successful thrombectomy in late time windows? Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery Published Online First: 17 June 2020. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. The Lancet 2016;387:1723–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liebeskind DS, Jahan R, Nogueira RG, et al. Impact of collaterals on successful revascularization in Solitaire FR with the intention for thrombectomy. Stroke 2014;45:2036–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nannoni S, Strambo D, Sirimarco G, et al. Eligibility for late endovascular treatment using DAWN, DEFUSE-3, and more liberal selection criteria in a stroke center. Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery 2020;12:842–7. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nosaka M, Ishida Y, Kimura A, et al. Time-dependent organic changes of intravenous thrombi in stasis-induced deep vein thrombosis model and its application to thrombus age determination. Forensic Sci Int 2010;195:143–7. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tetsuya Hashimoto, Mikito Hayakawa, Naoko Funatsu, et al. Histopathologic Analysis of Retrieved Thrombi Associated With Successful Reperfusion After Acute Stroke Thrombectomy. Stroke 2016;47:3035–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maekawa K, Shibata M, Nakajima H, et al. Erythrocyte-Rich Thrombus Is Associated with Reduced Number of Maneuvers and Procedure Time in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy. CEE 2018;8:39–49. doi: 10.1159/000486042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anetta Undas, Ariëns Robert A.S. Fibrin Clot Structure and Function. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2011;31:e88–99. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.230631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Celina Ducroux, Di Meglio Lucas Loyau Stephane, et al. Thrombus Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Content Impair tPA-Induced Thrombolysis in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2018;49:754–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laridan E, Denorme F, Desender L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemic stroke thrombi. Annals of Neurology 2017;82:223–32. doi: 10.1002/ana.24993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinjikji W, Starke RM, Murad MH, et al. Impact of balloon guide catheter on technical and clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:335–9. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen TN, Malisch T, Castonguay AC, et al. Balloon guide catheter improves revascularization and clinical outcomes with the Solitaire device: analysis of the North American Solitaire Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke 2014;45:141–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen TN, Castonguay AC, Nogueira RG, et al. Effect of balloon guide catheter on clinical outcomes and reperfusion in Trevo thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2019;11:861–5. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaidat OO, Mueller-Kronast NH, Hassan AE, et al. Impact of Balloon Guide Catheter Use on Clinical and Angiographic Outcomes in the STRATIS Stroke Thrombectomy Registry. Stroke 2019;50:697–704. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]