Abstract

Increased 5-hydroxytryptamine may be associated with the development and progression of inflammatory bowel disease. In this study, we examined the suppressive effect of flavonoids on the increased intra- and extracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine levels in rat mast RBL-2H3 cells, known to produce 5-hydroxytryptamine by the phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate stimulation. Among the flavonoids examined, luteolin and quercetin significantly reduced the cellular 5-hydroxytryptamine concentration. Gene and protein expression analyses revealed that luteolin significantly suppressed cellular tryptophan hydroxylase 1 expression induced by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate stimulation. Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling was also suppressed by luteolin, suggesting that this pathway is one of targets of 5-hydroxytryptamine modulation by luteolin. An in vivo experimental colitis model was prepared by administering 2.5% dextran sodium sulfate in drinking water to C57BL/6 mice for seven days. The ingestion of 0.1% dietary luteolin suppressed the increasing 5-hydroxytryptamine in the colorectal mucosa. In conclusion, luteolin possesses a suppressive effect on extensive 5-hydroxytryptamine formation in both experimental RBL-2H3 cells and colitis models.

Keywords: 5-hydroxytryptamine, tryptophan hydroxylase 1, RBL-2H3, luteolin, experimental colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is one of the chronic inflammatory disorders in patients. IBD patients often suffer from chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and melena.(1) These symptoms may disturb work activities and social interactions. Indeed, the quality of life in IBD patients does significantly decrease.(2) Currently, what exactly causes IBD is unknown. However, in recent years it has become clear that immune disorders occur and develop as the disease progresses due to various factors, such as genetics, environment, and intestinal bacteria abnormalities.(3)

5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin, 5HT) is an important neurotransmitter that regulates gastrointestinal motility.(4,5) However, excessive 5HT may be associated with IBD pathogenesis and aggravation.(6) Some reports indicate that 5HT producing cells, such as enterochromaffin (EC) cells and mast cells, are increased in IBD patient colons.(7,8) This was also observed in experimental models initiated by chemical administration.(9,10) In addition, 5HT directly or indirectly stimulates immune cells, such as macrophages and T cells.(6,11) It could worsen gut inflammation through enhanced proinflammatory cytokine excretion.(5,12)

It is known that more than 90% of 5HT is generated in the gastrointestinal tract.(13) EC cells predominantly produce 5HT, and mast cells may also contribute to a small degree. Tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the synthesizes of 5HT from tryptophan.(14) In human TPH exists in two isoforms: TPH-1 and TPH-2.(15) 5HT in the peripheral tissue is synthesized by TPH-1. Secreted 5HT binds 5HT receptors to influence gastrointestinal functions and immunity.(5,16) Secreted 5HT is incorporated into the surrounding epithelial cells by the serotonin transporter (SERT), is degraded to its aldehyde by monoamine oxidase, and metabolically converted to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Changes in TPH-1 and SERT expression are associated with an increase in 5-HT levels during IBD pathological conditions.(17,18) It has been reported that the polymorphism of the TPH-1 gene affects gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, which has some similarities with IBD.(19) The fact suggests that TPH-1 is a key factor for digestive symptoms.

There are some problems with IBD medication with 5-aminosalicylic acid because of undesirable side effects(20,21) or intolerance.(22) As an alternative medicine, various food ingredients can alleviate or prevent colitis.(23) Flavonoids are widely found in plants, fruits, vegetables, and herbs.(24) Flavonoids have broad biological functions such as anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer activities.(24) Indeed, flavonoids can improve or prevent IBD in rodent models.(25) For example, rutin ameliorated dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis possibly via the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) expression.(26) Apigenin supplementation also prevents DSS-induced colitis development by suppressing the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome.(27) Oral gavage luteolin administration also ameliorated DSS-induced colitis.(28)

As mentioned before, 5HT level modulation is one of the potential therapeutic targets for gut inflammation. However, the inhibitory effect of flavonoids on the 5HT level increase in colitis models remains to be examined. In this study, we compared the flavonoid effect on 5HT concentration modulation using RBL-2H3 cells, widely used in 5HT studies.(29–32) To elucidate the mechanism by which luteolin suppresses the increased intra- and extracellular 5HT concentration, we analyzed TPH-1 and SERT gene and protein expression. We also investigated the luteolin’s effect on signaling pathways involved in the intra- and extracellular 5HT increase. Furthermore, we confirmed that the luteolin ingestion does suppress the 5HT increase in colitis tissue.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Minimum Essential Media with Earle’s salts (MEM) and Chemi-Lumi One L were obtained from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: rabbit anti-tryptophan hydroxylase antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); rabbit anti-SERT (extracellular) antibody was purchased from Allomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel); rabbit anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2), rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2), rabbit anti-MEK 1/2, and rabbit anti-phospho-MEK 1/2 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); rabbit anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Medical and Biological Laboratories (Nagoya, Japan); and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G–horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was obtained from DAKO Japan (Tokyo, Japan). Luteolin (98%) for in vivo experiments was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Luteolin (99%) for in vitro experiments, kaempferol, cyanidin chloride, and myricetin were obtained from Extrasynthese (Lyon, France). DSS was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA). Apigenin, rutin, quercetin dihydrate, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), ImmunoStar LD®, PD98059, and ISOGEN I were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). 5-Hydroxytryptamine-d4 (d4-5HT) hydrochloride was obtained from Medical Isotope Inc. (Pelham, NH). EzBlock Chemi was purchased from ATTO (Tokyo, Japan).

Cell culture and treatment

RBL-2H3 cells were obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan). The cells were maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Typically, the cells were treated with various flavonoids or PD98059 in FBS-free MEM for 30 min. Then, 25 nM PMA was added to each well and further incubated for a range of time. PMA and each flavonoid were dissolved in DMSO, and the final DMSO concentration was 0.12%. To assess cell viability, cells (3.0 × 104 cells) were seeded and cultured in 96-well plates for 24 h. The cells were treated with flavonoids at various concentrations or with 5 μM of the inhibitor in FBS-free MEM medium for 30 min. PMA (25 nM) was added to each well and further incubated for 10 h. After treatment, cell viability was assessed by Cell Count Reagent SF according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription

Cells were seeded into 12-well culture plates at a density of 4.5 × 105/well and then cultured overnight. After incubation, the cells were treated as described in the “Cell culture and treatment” section. Total RNA was extracted using ISOGEN I according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcribed cDNA was prepared using an iScriptTM Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). cDNA was subjected to quantitative reverse-transcription (qRT)-PCR amplification using MyGo (IT-IS Life Science Ltd, Mahon, Cork, Ireland). The qRT-PCR was performed using MyGo Green Mix Universal (IT-IS Life Science) with previously reported primers for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), TPH-1, and SERT.(32–34) The PCR conditions consisted of 45 cycles with 15 s of denaturation at 95°C, 60 s of annealing, and extension at 60°C. Relative levels of gene expression in each sample were calculated using the comparative ΔΔCt method.

Western blotting

Cells (4.5 × 105/well) were seeded into 12-well culture plates and allowed to attach to the wells overnight. The cells were treated as described in the “Cell culture and treatment section”. After the treatments, the cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed using M-PER with protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), phosphatase inhibitor cocktails II, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails III (Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were centrifuged, and lysate protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit. The protein samples were mixed with loading buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 10% polyacrylamide gels, and electro-transferred on to Immobilon-P Transfer Membranes (Merck-Millipore, MA). The membrane was blocked with EzBlock Chemi for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the membrane three times for 10 min each with 0.1% Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), the membrane was incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody against TPH-1 (1:500 dilution), SERT (1:500), ERK (1:500), Phospho-ERK (1:500), MEK (1:500), Phospho-MEK (1:500), or β-actin (1:2,000) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (1:2,000 for TPH-1, SERT, and ERK, or 1:10,000 for β-actin) in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed again and protein bands were visualized using ImmunoStar® LD or Chemi-Lumi One L. The image was captured by GeneGnome with GeneSys software ver. 1.6.9.0 (SYNGENE, Bangalore, India).

5HT quantification

Tissue 5HT was measured according to a previous report(35) with some modifications. In brief, the colorectal mucosa (approximately 10 mg) was homogenized in 140 μl ice-cold 0.1% formic acid in water and centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant (75 μl) was mixed with 25 μl internal standard d4-5HT (IS, 25 μM). To precipitate proteins, 4 vol. of acetonitrile (CH3CN) was added to the supernatant and then centrifuged (14,000 g, 4°C for 10 min). The supernatant was passed through a solid-phase extraction column (Discovery DSC-18, 500 mg). After washing with 2 ml of methanol/0.1% formic acid in water (5:95, v/v), the supernatant was then eluted with 3 ml of 0.1 M ammonium acetate in methanol. The eluted samples were then evaporated to dryness using vacuum-centrifugation. Finally, the dry residue was reconstituted with a mobile phase liquid (0.1% formic acid in water/CH3CN [9:1, v/v]) and then centrifuged (10,000 g, 4°C for 5 min). The supernatant was then transferred to a vial.

For cell medium (extracellular) samples, cells were treated as described in the “Cell culture and treatment” section, and the cell culture medium (200 μl) was then collected. CH3CN containing 100 nM IS (800 μl) was added to the medium and centrifuged (14,000 g, 4°C for 10 min) for protein removal. For intracellular 5HT, the treated cells were washed by ice-cold PBS followed by lysis with 400 μl of 0.1 M NaOH. The lysate was adjusted to approximately pH 3 by adding HCl. CH3CN (800 μl) containing 100 nM IS was then added to the lysate (200 μl) and centrifuged. The respective supernatant was then transferred to a vial.

The 5HT contents in the samples were measured by liquid chromatography connected with a quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer [LC/MS/MS (QqQ), a Xevo TQD (Waters, Milford, MA) or API3000 (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA)]. The separation was performed by HPLC [Acquity UPLC H-class (Waters) or Agilent HP1100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA)] with a COSMOSIL PBr (2 × 150 mm, 5 μm; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) at 0.2 ml/min using 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and CH3CN (solvent B). The gradient program was as follows: initial B10%, 1 min B10%, 10 min B55%, 14 min B90%, 15 min B10%, and 30 min B10%. Five microliters of the sample were injected. Positive multiple-reaction monitoring transitions were selected as follows: 5HT 177.1/160.2; IS d4-5HT 181.2/164.4.

Animal experiments

The study was approved by the University of Hyogo Ethics Committee (No: 171, 236). A total of 20 6-week-old male C57BL/6N mice were obtained from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and housed in controlled conditions [21°C, 50 ± 10% humidity, with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on from 9:00 to 21:00)]. After a one-week adaption, mice were randomly divided into three experimental groups: control (n = 5) and DSS groups (n = 10) were fed a standard diet AIN-93G for 14 days. The DSS + LUT groups (n = 5) were fed luteolin (0.1% w/w) with the AIN-93G diet.

After acclimation, the DSS and DSS + LUT mice received distilled drinking water ad libitum containing 2.5% (w/v) DSS for 7 days, while the control group was given plain distilled water. The drinking water (with or without DSS) in a bottle was replaced with freshly prepared water once every two days. The body weight of each mouse was recorded every day. Disease activity index (DAI) scores, which were based on body weight loss, stool consistency, and stool bleeding, were calculated as previously described.(36) On day 14, the mice were euthanized under anesthesia using isoflurane, and the blood was immediately collected from the inferior vena cava. The colon length from the proximal colon to the rectum was measured. The colon was washed with ice-cold PBS, the colorectal mucosa was scraped off, and the mucosa was frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at −80°C until needed.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity

MPO activity was measured by a method described previously.(37) Briefly, the isolated colon was homogenized in 50 mM hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide buffer (pH 6.0) at 50 mg wet tissue/ml. After removing debris by centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated with 0.53 mM o-dianisidine dihydrochloride and 0.2 mM H2O2 in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). The change in absorbance at 450 nm was measured. One MPO activity unit was defined by the consumption of 1 μmol peroxide per minute at 25°C. The activity was expressed as MPO units per mg tissue protein.

Statistical analysis

The animal experiment data shown are representative of two independent experiments. The cell experiments are representative of three independent experiments. Each data was statistically analyzed using Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA test with multiple-comparison posthoc analysis (Tukey’s or Games-Howell) using SPSS ver. 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) software. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Luteolin significantly reduced the intra- and extracellular 5HT levels in RBL-2H3 cells

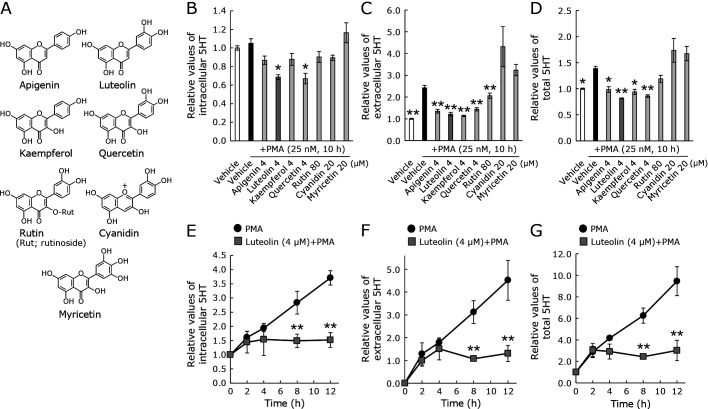

In our study, the 5HT levels in RBL-2H3 cells were time-dependently increased using PMA as a stimulant. Using this cellular model, we compared seven flavonoids (Fig. 1A) to assess their modulatory effects on 5HT production, excretion, and incorporation. Each flavonoid concentration used for all assays was its maximum concentration that did not cause cytotoxicity. Among the flavonoids used, only luteolin and quercetin significantly suppressed intracellular, extracellular, and total 5-HT levels (Fig. 1B–D). Because luteolin, but not quercetin, suppresses inflammatory symptoms in chemically induced colitis models,(28,38) we focused on luteolin hereafter. Next, the luteolin’s effect on 5HT levels was examined. Both intra- and extracellular 5-HT levels were increased by the PMA stimulation in a time-dependent manner. The increases during 8–12 h were extensively suppressed by luteolin treatment (Fig. 1E–G).

Fig. 1.

The flavonoid effects on extracellular and intracellular 5-HT levels in RBL-2H3 cells. Cells were treated with a vehicle or the respective seven flavonoids for (A) 30 min followed by 25 nM PMA stimulation for the indicated time. Intracellular 5HT (B), extracellular 5HT (C), and total 5HT (D) were quantified as described in the Materials and Methods. Time-dependent changes in intracellular, extracellular, and total 5HT levels by luteolin or vehicle are shown in (E–G). Control was 0 h with fresh serum-free medium. The 5HT concentrations were adjusted to the relative control. Data represent the means ± SE. Statistical significance was set at *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs vehicle with PMA using Tukey’s multiple-comparison posthoc test (B–D) or Student’s t test (E–G).

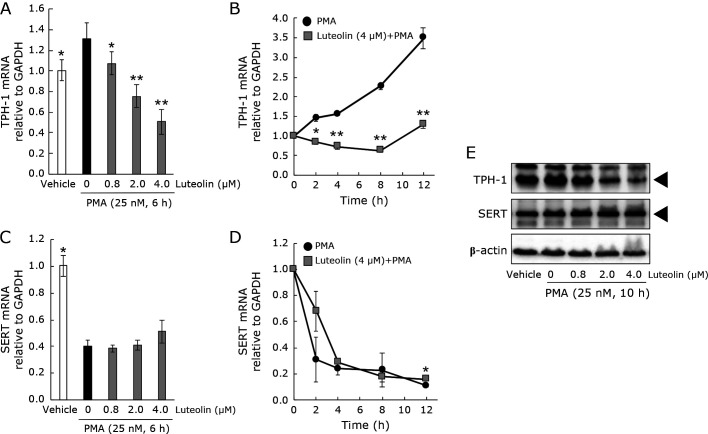

The luteolin effect on TPH-1 and SERT expression

To begin to understand the molecular mechanisms of 5HT modulation by luteolin, TPH-1 and SERT expression in RBL-2H3 cells was examined (Fig. 2A–E). A 6-h incubation of luteolin (0–4 μM) dose-dependently suppressed TPH-1 mRNA expression induced by PMA (Fig. 2A). A 12-h incubation (4 μM) completely suppressed the PMA-induced TPH-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 2B). The PMA-induced TPH-1 protein upregulation was also suppressed by luteolin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2E). The PMA treatment downregulated SERT mRNA but not SERT protein (Fig. 2C–E). Luteolin had no significant effect on SERT expression, except the mRNA expression after 12 h PMA stimulation (Fig. 2C–E).

Fig. 2.

The luteolin effect on TPH-1 and SERT expression in RBL-2H3 cells. Cells were treated with luteolin (0–4.0 μM) for 0–12 h and then stimulated by PMA for 6 h (for genes) or 10 h (for proteins). The dose-dependent or time-dependent changes of TPH-1 or SERT mRNA expression are shown (A–D). GAPDH mRNA was the internal control. After incubation with PMA, proteins were isolated and probed using Western blotting with anti-TPH-1, anti-SERT, or β-actin antibody (E). Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. The black triangle means the location of the TPH-1 or SERT. Data represent the means ± SE. Statistical significance was set at *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs vehicle + PMA using Games-Howell multiple-comparison posthoc test.

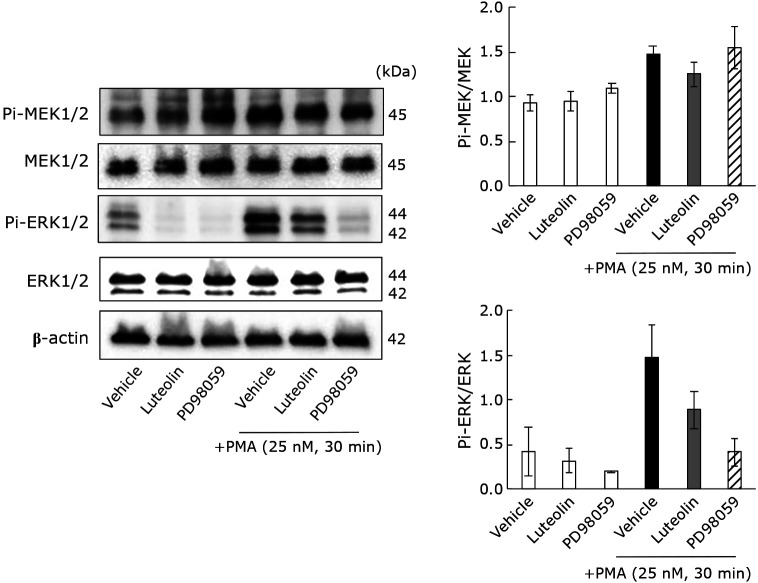

The MEK/ERK signaling pathway effect on 5HT production

Previous studies reported that extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) phosphorylation affects 5HT generation and secretion from neoplastic EC cells (KRJ-I).(39,40) Therefore, we confirmed whether 5HT production responds to the MEK/ERK signaling pathway in the PMA-stimulated cells using a specific MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor, PD98059. The extracellular and total 5HT levels were significantly decreased by PD98059, while the intracellular 5HT concentrations did not change (Supplemental Fig. 1A–C*). PD98059 also suppressed TPH-1 mRNA and protein expression (Supplemental Fig. 1D and E*). We then investigated the luteolin effect on MEK and ERK phosphorylation levels (Fig. 3). The phosphorylated MEK (Pi-MEK1/2) and ERK (Pi-ERK1/2) levels increased after PMA stimulation, and the ERK phosphorylation tended to decrease following luteolin treatment.

Fig. 3.

The luteolin suppresses the MEK/ERK signal pathway which may contribute to 5HT increase in RBL-2H3 cells by PMA stimulation. Cells were treated with luteolin (4 μM) or PD98059 (5 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated by PMA for 30 min. Proteins were isolated, separated, and blotted with anti-phosphorylated MEK, anti-MEK, anti-phosphorylated ERK, anti-ERK, or anti-β-actin antibody. The relative semiquantitative analysis was based on optical density by ImageJ software, ver. 1.41 (National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD).

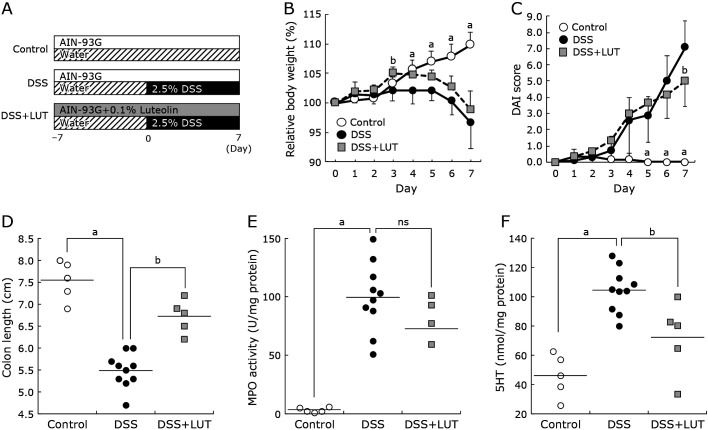

Luteolin attenuated DSS-induced colitis and reduced the elevated 5HT levels in colorectal mucosa

To examine the in vivo luteolin effect on 5HT modulation, the inflammation extent in a DSS-induced colitis murine model was first estimated by evaluating the body weight alteration rate, colon length shortening, and DAI score (Fig. 4A). Neutrophil infiltration into the colorectal mucosa was also measured by MPO activity. Before the experiment, we confirmed that a luteolin diet without DSS did not affect body weight and other indexes (unpublished observation). The body weight of 2.5% DSS-treated mice decreased significantly from day-4 compared with control. DSS + LUT (0.1% luteolin and DSS) mice also decreased in weight (Fig. 4B). The luteolin diet improved the DAI score and partly prevented the colon length shortening induced by DSS for seven days (Fig. 4C and D). Luteolin supplementation attenuated the increasing rate of MPO activity by DSS challenge (Fig. 4E). The increased 5HT level in DSS-induced colitis mice mucosa was also significantly reduced by the luteolin diet (p<0.05, Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

The dietary luteolin effect on disease manifestations, myeloperoxidase activity, and mucosal 5HT in DSS-induced colitis mice. (A) Experimental design of DSS colitis induction with control or luteolin diet. The animals were split into three groups: control, DSS, and DSS + LUT groups as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. Seven-week old mice were fed with a standard diet (the control or DSS group) or received a diet supplemented with 0.1% luteolin (DSS + LUT group). Colitis was induced by administering 2.5% DSS in drinking water for both DSS and DSS + LUT groups. (B) The body weight change rate. (C) Disease activity index (DAI) score. (D) Colon length. (E) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in colorectal tissue. (F) 5HT contents in colorectal mucosa. Control: open circle, DSS: closed circle, DSS + LUT: light gray square. Groups were compared by Tukey’s or Games-Howell multiple-comparison posthoc test (n = 5 mice for control and DSS + LUT groups, n = 10 mice for DSS group). Data represent the means ± SE. Significance was compared with the DSS treatment group. Values designated by different letters (a, b) are significantly different (p<0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we found that luteolin can suppress the increase in 5HT and TPH-1 expression in PMA-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. Luteolin also showed the suppressive effects on 5HT increment in DSS-challenged mice colorectal mucosa. Firstly, we evaluated the effect of seven flavonoids on 5HT modulation using the cultured cells. Among them, the catechol-type flavonoids except cyanidin (anthocyanidin), luteolin and quercetin, suppressed both intra- and extracellular 5HT increases (Fig. 1B and C). The detailed structure-activity relationship for 5HT modulation remains to be elucidated. Since luteolin suppresses chemical-induced intestinal inflammation,(28,38) luteolin was selected for further study.

Multiple mechanisms for the increase in 5HT under inflammatory conditions might be underlying in vivo and in vitro. TPH-1 knockouts delay onset of inflammatory disease and decrease its severity in the DSS-induced colitis model.(41) Blocking peripheral 5HT synthesis by a TPH inhibitor reduces the severity of chemical-induced intestinal inflammation.(42) The SERT expression level is considered to be another important determinant of the extracellular 5HT amount. It has been reported that ulcerative colitis patients and chemical-induced colitis mice reduce SERT immunoreactivity and/or mRNA expression.(43,44) SERT knockout mice have significantly worse intestinal inflammation.(45) Then we focused on the TPH-1 and SERT expression changes from key regulators for intra- and extracellular 5HT levels when luteolin was supplemented in RBL-2H3 cells. Luteolin suppressed the increased TPH-1 mRNA and protein expression stimulated by PMA (Fig. 2A, B, and E), suggesting that TPH-1 is one of the critical molecules targeted by luteolin. As far as we know, there is no report on TPH-1 suppression affected by a flavonoid. By contrast, luteolin did not modulate SERT expression (Fig. 2D and E). Previous studies showed that luteolin activates SERT in rat SERT-overexpressing Chinese hamster ovary cells.(46) To estimate the influence of luteolin on SERT-dependent 5HT production, it will be necessary to investigate the SERT expression on the cell membrane and also its activity in RBL-2H3 cells.

The increased ERK phosphorylation may be involved in 5HT synthesis and release in KRJ cells.(39) Pretreating RAW 264.7 cells with luteolin inhibited LPS-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation.(47) Indeed, luteolin suppressed MEK and ERK phosphorylation in RBL-2H3 cells stimulated by PMA (Fig. 3). In addition to the MEK-ERK signal, luteolin affects various molecular signals, such as ion channels, receptors, and other signaling pathways,(48,49) possibly resulting in suppressing intra- and extracellular 5HT levels. Therefore, an advanced study is required to elucidate the precise molecular mechanism of 5HT suppression by luteolin.

Concerning dietary luteolin in vivo, DSS-treated mice increased 5HT levels in colon mucosa approximately 2.3-fold higher than compared with control mice, along with increased DAI score and other biochemical indexes (Fig. 4C–F). The luteolin diet (0.1%) partially improved colitis symptoms, including DAI score and colon length shortening. Luteolin supplementation improves colitis by oral administration,(28,38,50) and dietary supplementation with 0.1% luteolin is also effective in mice. Besides, we revealed that the 5HT level increased by DSS treatment was significantly suppressed by the luteolin diet (Fig. 4F). It is noteworthy that the 5HT increase in the DSS colitis model may be due to the increased EC cells and TPH-1 expression, as well as increased interleukin 13 and intestinal flora.(51,52) To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that luteolin intake suppressed mucosal 5HT in a colitis model. In contrast, the current study could not provide the outcome of in vivo modulation of TPH-1 expression by dietary luteolin; it is a remaining task to be determined. Furthermore, the changes in SERT expression should be evaluated to understand the regulatory mechanism of the local 5HT level in near future.

In conclusion, this study revealed that luteolin reduces the 5HT levels, at least in part, by inhibiting TPH-1 in RBL-2H3 cells. This mechanism may also be applicable for in vivo 5HT suppression by luteolin administration. However, this is just the start of uncovering the full mechanism. Dietary luteolin may have the potential to ameliorate inflammatory conditions by decreasing overproduced 5HT.

Author Contributions

NS planned and performed all experiments, and wrote the draft of this paper. AM and YN discussed the data and helped to write this paper. HA and TN advised and supported this study. YK supervised, wrote, and edited the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the Iijima Memorial Foundation for the Promotion of Food Science and Technology. We are thankful to Ms. Yuki Saito for supporting the animal experiments.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Bernstein CN. Large registry epidemiology in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017; 23: 1941–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, Hommes D, Bell C, Avedano L. IBD and health-related quality of life—discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8: 1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mentella MC, Scaldaferri F, Pizzoferrato M, Gasbarrini A, Miggiano GAD. Nutrition, IBD and gut microbiota: a review. Nutrients 2020; 12: 944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gershon MD. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2013; 20: 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shajib MS, Khan WI. The role of serotonin and its receptors in activation of immune responses and inflammation. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015; 213: 561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan M, Ding L, Wang D, Han J, Gao P. Serotonin: a potent immune cell modulator in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Salhy M, Danielsson A, Stenling R, Grimelius L. Colonic endocrine cells in inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med 1997; 242: 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoyanova II, Gulubova MV. Mast cells and inflammatory mediators in chronic ulcerative colitis. Acta Histochem 2002; 104: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG. Changes in enteroendocrine and immune cells following colitis induction by TNBS in rats. Mol Med Rep 2016; 14: 4967–4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oshima S, Fujimura M, Fukimiya M. Changes in number of serotonin-containing cells and serotonin levels in the intestinal mucosa of rats with colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate. Histochem Cell Biol 1999; 112: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.León-Ponte M, Ahern GP, O'Connell PJ. Serotonin provides an accessory signal to enhance T-cell activation by signaling through the 5-HT7 receptor. Blood 2007; 109: 3139–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herr N, Bode C, Duerschmied D. The effects of serotonin in immune cells. Front Cardiovasc Med 2017; 4: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gershon MD, Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 397–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKinney J, Teigen K, Frøystein NA, et al. Conformation of the substrate and pterin cofactor bound to human tryptophan hydroxylase. Important role of Phe313 in substrate specificity. Biochemistry 2001; 40: 15591–15601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan WI, Ghia JE. Gut hormones: emerging role in immune activation and inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol 2010; 161: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin JG, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Grider JR. Propulsion in guinea pig colon induced by 5-hydroxytryptamine (HT) via 5-HT4 and 5-HT3 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 288: 93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tada Y, Ishihara S, Kawashima K, et al. Downregulation of serotonin reuptake transporter gene expression in healing colonic mucosa in presence of remaining low-grade inflammation in ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 31: 1443–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Schipper ME, ter Linde JJ, Samsom M. Serotonin synthesis and uptake in symptomatic patients with Crohn’s disease in remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5: 714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katsumata R, Shiotani A, Murao T, et al. The TPH1 rs211105 gene polymorphism affects abdominal symptoms and quality of life of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2018; 62: 270–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curkovic I, Egbring M, Kullak-Ublick GA. Risks of inflammatory bowel disease treatment with glucocorticosteroids and aminosalicylates. Dig Dis 2013; 31: 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 2016: CD000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Paolo MC, Paoluzi OA, Pica R, et al. Sulphasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid in long-term treatment of ulcerative colitis: report on tolerance and side-effects. Dig Liver Dis 2001; 33: 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hossen I, Hua W, Ting L, et al. Phytochemicals and inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2020; 60: 1321–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panche AN, Diwan AD, Chandra SR. Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutr Sci 2016; 5: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salaritabar A, Darvishi B, Hadjiakhoondi F, et al. Therapeutic potential of flavonoids in inflammatory bowel disease: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 5097–5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon KH, Murakami A, Tanaka T, Ohigashi H. Dietary rutin, but not its aglycone quercetin, ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in mice: attenuation of pro-inflammatory gene expression. Biochem Pharmacol 2005; 69: 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radulovic K, Normand S, Rehman A, et al. A dietary flavone confers communicable protection against colitis through NLRP6 signaling independently of inflammasome activation. Mucosal Immunol 2018; 11: 811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Shen L, Luo H. Luteolin ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice possibly through activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2016; 40: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu CB, Steiner JA, Munn JL, Daws LC, Hewlett WA, Blakely RD. Rapid stimulation of presynaptic serotonin transport by A3 adenosine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007; 322: 332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SW, Park SY, Hwang O. Up-regulation of tryptophan hydroxylase expression and serotonin synthesis by sertraline. Mol Pharmacol 2002; 61: 778–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baik SY, Jung KH, Choi MR, et al. Fluoxetine-induced up-regulation of 14-3-3zeta and tryptophan hydroxylase levels in RBL-2H3 cells. Neurosci Lett 2005; 374: 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao R, Wang S, Huang Z, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced serotonin transporter up-regulation involves PKG-I and p38MAPK activation partially through A3 adenosine receptor. Biosci Trends 2015; 9: 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F, Zhang M, Xu D, et al. Co-administration of paroxetine and pravastatin causes deregulation of glucose homeostasis in diabetic rats via enhanced paroxetine exposure. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2014; 35: 792–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suga N, Murakami A, Nakamura Y, et al. Cytotoxic and cytoprotective effects of tryptamine-4,5-dione on neuronal cells: a double-edged sword. Free Radic Res 2017; 51: 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wojnicz A, Ortiz JA, Casas AI, Freitas AE, López MG, Ruiz-Nuño A. Data supporting the rat brain sample preparation and validation assays for simultaneous determination of 8 neurotransmitters and their metabolites using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Data Brief 2016; 7: 714–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandurangan AK, Mohebali N, Norhaizan ME, Looi CY. Gallic acid attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in BALB/c mice. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015; 9: 3923–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JJ, Shajib MS, Manocha MM, Khan WI. Investigating intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced model of IBD. J Vis Exp 2012; 60: 3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishitani Y, Yamamoto K, Yoshida M, et al. Intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of luteolin: role of the aglycone in NF-κB inactivation in macrophages co-cultured with intestinal epithelial cells. Biofactors 2013; 39: 522–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chin A, Svejda B, Gustafsson BI, et al. The role of mechanical forces and adenosine in the regulation of intestinal enterochromaffin cell serotonin secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012; 302: G397–G405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kidd M, Modlin IM, Gustafsson BI, Drozdov I, Hauso O, Pfragner R. Luminal regulation of normal and neoplastic human EC cell serotonin release is mediated by bile salts, amines, tastants, and olfactants. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008; 295: G260–G272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghia JE, Li N, Wang H, et al. Serotonin has a key role in pathogenesis of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 1649–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JJ, Wang H, Terc JD, Zambrowicz B, Yang QM, Khan WI. Blocking peripheral serotonin synthesis by telotristat etiprate (LX1032/LX1606) reduces severity of both chemical- and infection-induced intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015; 309: G455–G465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bertrand PP, Barajas-Espinosa A, Neshat S, Bertrand RL, Lomax AE. Analysis of real-time serotonin (5-HT) availability during experimental colitis in mouse. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010; 298: G446–G455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, et al. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 1657–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bischoff SC, Mailer R, Pabst O, et al. Role of serotonin in intestinal inflammation: knockout of serotonin reuptake transporter exacerbates 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009; 296: G685–G695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao G, Qin GW, Wang J, Chu WJ, Guo LH. Functional activation of monoamine transporters by luteolin and apigenin isolated from the fruit of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. Neurochem Int 2010; 56: 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xagorari A, Roussos C, Papapetropoulos A. Inhibition of LPS-stimulated pathways in macrophages by the flavonoid luteolin. Br J Pharmacol 2002; 136: 1058–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ambasta RK, Gupta R, Kumar D, Bhattacharya S, Sarkar A, Kumar P. Can luteolin be a therapeutic molecule for both colon cancer and diabetes? Brief Funct Genomics 2018; 18: 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aziz N, Kim MY, Cho JY. Anti-inflammatory effects of luteolin: a review of in vitro, in vivo, and in silico studies. J Ethnopharmacol 2018; 225: 342–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vukelić I, Detel D, Batičić L, Potočnjak I, Domitrović R. Luteolin ameliorates experimental colitis in mice through ERK-mediated suppression of inflammation, apoptosis and autophagy. Food Chem Toxicol 2020; 145: 111680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agus A, Planchais J, Sokol H. Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018; 23: 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shajib MS, Wang H, Kim JJ, et al. Interleukin 13 and serotonin: linking the immune and endocrine systems in murine models of intestinal inflammation. PLoS One 2013; 8: e72774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.