Abstract

Background

The world is facing the current COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic response is affecting routine health care provision all over the world. We aimed to review the relevant literature and highlight challenges in the provision of routine care for patients with diabetes during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Embase databases up till August 13, 2020 and retrieved relevant articles published on difficulties on routine diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

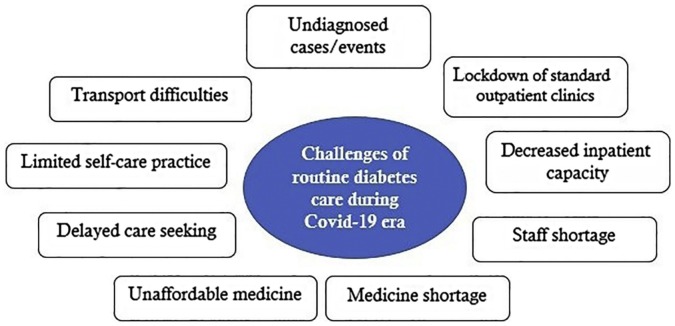

Through our reading of the recent literature discussing the difficulties of routine healthcare provision for patients with diabetes amid the COVID-19 pandemic, we have identified nine themes as follows: lockdown of standard outpatient clinics, decreased inpatient capacity, staff shortage, medicine shortage, unaffordable medicine, delayed care seeking, limited self-care practice, transport difficulties, and undiagnosed cases/events.

Conclusion

Diabetes management during lockdown is particularly challenging. This review specified a summary of difficulties of diabetes care during COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare policy makers as well as healthcare providers could take advantage of the results of this review to mitigate the adverse effect of the crisis on provision of routine care for diabetes as well as other chronic conditions.

Keywords: Diabetes, Diabetes management, COVID-19, Pandemic, Narrative review

1. Introduction

In December 2019, an unprecedented number of patients with pneumonia of unknown cause presented in adult individuals from Wuhan, China [1]. High transmissibility of the virus, especially among asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic carriers [2], alongside with the apparent absence of any cross-protective immunity from related viral infections [3], has now resulted in a worldwide outbreak, now classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization [4]. As of August 13, 2020, there has been more than 20.5 million confirmed cases globally, and around 750,000 fatalities [5]. As a result, countries are responding to contain the spread of disease through national or local lockdowns. Apart from the general public, the health care systems have been particularly affected by these lockdowns [6].

Currently, the bulk of global healthcare resources are focused on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). As a result of this resource reallocation, concern is increasing that COVID-19 will disrupt the continuum of care for patients with other diseases. It is of outmost importance to continue routine care in spite of the pandemic, to avoid a rise in non-COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality. This is especially true when considering experiences gained from previous outbreaks. For example, reports from the Ebola outbreak in 2014–2015 suggest that indirect mortality from treatable conditions attributable to health system failures exceeded direct mortality from Ebola [7].

Diabetes continue to constitute a crucial public health issue on a global scale, that require ongoing healthcare management over time. This chronic condition increases the risk of disabling and life-threatening complications from micro- and macro-vascular diseases. It is estimated that, only in 2013, approximately 380 million adults were living with diabetes (all types), and this number will rise to 590 million by 2035 [8]. In addition to its direct health consequences, diabetes has emerged as an independent predictor of worse prognosis in patients with COVID-19. It is now well-established that quality healthcare services can postpone diabetes related complications and is necessary to enhance the quality of the patient’s life [9]. In addition, considering COVID-19 pandemic, poor glycaemic control is known to be associated with immune suppression [10], and thus as a significant contributor to COVID-19 severity.

With so much that is unknown about the COVID-19 disease itself, it is very clear that even less is known about how healthcare systems can contain such a crisis and simultaneously provide continuum of care for other conditions such as diabetes. In this circumstance, healthcare service stakeholders are obliged to share their experiences in order to pool together helpful information that will help to mitigate the situation, for example by sharing perceived and experienced barriers regarding the routine healthcare services. In this review article, we have systematically searched the medical databases and collated and narratively reviewed all the available evidences that have emerged so far on barriers to routine diabetes care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials & methods

Due to the novelty and complexity of the issues and research question and the aim to provide timely support for healthcare policy makers and providers, as method, a narrative review was chosen. We searched the PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Embase databases for articles on SARS-CoV-2 and diabetes using the following search terms: “diabetes mellitus”, “Type 1 diabetes mellitus”, “Type 2 diabetes mellitus”, “new onset diabetes”, “hyperglycaemia”, “ketoacidosis”, “anti-diabetic drug”, “ACE-inhibitors”, and “hydroxychloroquine”, in conjunction with the terms “COVID-19” and “SARS-CoV-2 infection”. We also checked reference lists in relevant articles and Google Scholar for additional references.

This search was last updated on 8 August 2020. We screened the results on title and abstract for relevant information. Starting from the articles found in this search, we used a snowball search strategy, scanning reference lists in articles and Google Scholar for retrieving those that were relevant. A thematic analysis was undertaken to provide a rich synthesis of the findings of interest across the reviewed publications [11].

3. Results

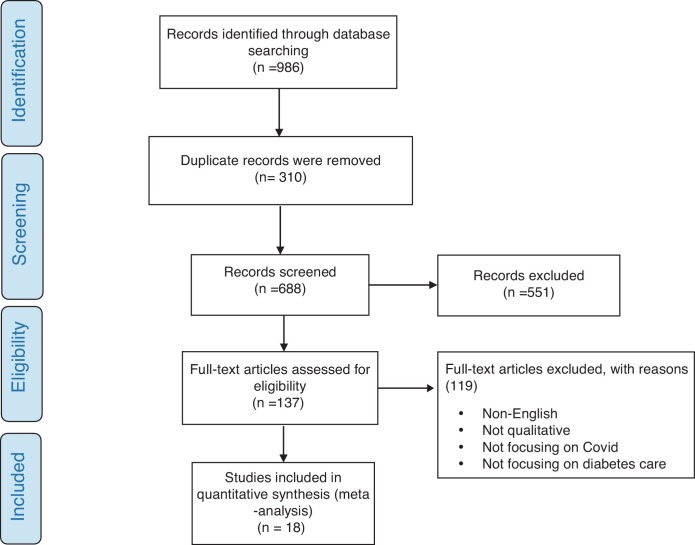

The applied search strategy retrieved 986 citations, of which 310 were duplicates and removed. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of study selection. After title and abstract screening, 551 citations were excluded and 119 citations were considered potentially relevant and were assessed in detail. Finally, 18 studies met inclusion criteria and incorporated into the meta-synthesis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

3.1. Challenges of routine diabetes management during COVID-19 era

Through our reading of the recent literature discussing the difficulties of routine healthcare provision for patients with diabetes amid the COVID-19 pandemic, we have identified nine themes as follows (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Challenges of routine diabetes care during COVID-19 era.

3.1.1. Lockdown of standard outpatient clinics

Its well-documented that conditions such as diabetes require regular, usually face‐to‐face contact with several healthcare providers including GPs, endocrinologists, diabetes educators, dieticians and podiatrists to optimize glycemic control [12]. However, in response to COVID-19 management, outpatient and secondary care facilities have been pushed to limit or cancel their routine health service provision in order to mobilize healthcare providers to other high-pressure areas as well as reducing the numbers of patients attending healthcare facilities unnecessarily. This lock down of standard outpatient clinics [13] can create major long-term issues for patients with diabetes in terms of continuity of care, raising concerns of significant unmet clinical needs. The few active healthcare facilities may also be limited by the shortage of disinfectant products that may impede sterilization techniques for service provisions such as insulin injections and blood glucose monitoring, and promote infection [14].

3.1.2. Decreased inpatient capacity

The high influx of COVID-19 patients over-utilized and stretched hospitals capacities [15], and as a results, access to inpatient care is diminished for patients with other conditions, such as diabetes, who are in urgent need [16]. In addition, this issue may be even more complicated when some hospitals ask patients to provide documentations proving negative COVID-test before allowing admission. This issue adds to the total costs of treatment, which might complicate receiving of inpatient care for patients with diabetes [16].

3.1.3. Staff shortage

Effects on staffing level in diabetes services affected by COVID-19 have led to several important difficulties, most of which are related to availability of healthcare staff [15]. First, a considerable number of diabetes staff (including inpatient specialist and nurses) have been seconded to COVID specific activities and wards [13]. This has been done at short notice and without full detailed consideration of the prominent role diabetes teams play in preventing harm to people with diabetes, both in hospital and in the community [17]. This problem may also reduce allied health professional input. For example, many allied healthcare professionals including podiatrists, orthotics specialists, as well as specialist nurses have significant role in managing diabetes complications, such as diabetic food disease. The reduction in this allied health professional input may leave a big gap in the provision of such essential services where patients may be left to fend for themselves [15]. Additionally, the pandemic also has limited the availability of healthcare providers due to loss of healthcare providers who may be quarantined, infected, or required to care for family [15].

3.1.4. Medicine shortage

It is well documented that drug and equipment shortage could lead to serious consequences when it comes to patient outcomes, especially for patients with diabetes. Procurement of insulin, other medicines, dressings for ulcers and wounds, offloading devices and self-monitoring tools is an important challenge, both in terms of national supply and of distribution throughout countries amid the ongoing restrictions [18]. Decreased health budget due to severe damage to national economies threat availability of medicines and other supplies critical for diabetes care [19]. This problem seems to be more complicated in low resource countries, in which more than 80% of patients with diabetes live. There are also several trade barriers during the COVID-19 era. For example, it is still even unknown when the global trading channels will reopen [14,19,20]. This issue is more highlighted in case of some diabetes medications such as insulin given its cold-chain requirements.

3.1.5. Unaffordable medicine

Unaffordable medicine or other medical products is a prevalent difficulty in most of countries, even in non-pandemic times. Now during the COVID-19 crisis, many families and individuals have lost their income [18,19]. These lockdowns challenge financial aspect of access to necessary medicine amid the pandemic. On the other hand, prescriptions of glucose-lowering medicines require physician approval to reimburse the cost. This issue poses a financial hardship for patients in the current situation that most of face-to-faced visit have been concealed [21].

3.1.6. Delayed care seeking

Less access to investigations and face-to-face consultations is not caused only by decreased clinic activities. There is increasing evidence that patients in need of healthcare services, among them patients with diabetes, are avoiding medical clinics because of perceived COVID-19 exposure risk [13,18]. This is especially true for patients with diabetes given the fact that patients with diabetes tend to be at increased risk of poorer outcomes from COVID-19 infection compared to patients without diabetes [22].

3.1.7. Limited self-care practice

Lockdowns imposed by governments have also made self-care more difficult for people with diabetes. Firstly, lockdown and social distancing drives risk for community containment that implies limited physical activities of the people with diabetes [14,18,[23], [24], [25]]. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, they can no longer access gyms, swimming pools and related facilities [15]. For example, a study from Brazil showed that, among patients with diabetes, physical activity was the most impacted, with a reduction reported by 59.5% of the respondents [25]. In addition, restriction in outdoor movements would limit the sunlight exposure leading to vitamin D deficiency, that may lead to insulin resistance [26].

Secondly, lockdown measures have adversely affected many patients who used to maintain healthy dietary habits. The lockdowns restricted healthy food supplies [24], increased food price [19], and increased carbohydrate consumption [14,27]. The resulted food insecurity, as well as having to change diets make consistent diabetes self-management challenging [19].

Lastly, there are many concerns about the adverse effect of the pandemic on mental health and well-being [18,23], especially in patients with diabetes that are more prone to mental health issues than the general population [36]. This issue can worse self-care practice as well as adherence to treatment [21], as seen both during and after disasters [21].

This combination of reduced physical activity, reduced healthy diet habits, and mental health issues can culminate in poor diabetes management further increasing the risk of complications [15].

3.1.8. Transport difficulties

Where provisions have been established for face to face investigations; patients are finding it difficult to find a way to get to healthcare facilities, because the lockdown took the form of severe restrictions on transport [15]. It is important to remember that the majority of this patient cohort often have some types of musculoskeletal foot complication and limited mobility [28]. These conditions may be fitted with offloading devices that makes it even more difficult for them to travel.

3.1.9. Undiagnosed cases/events

Lockdown-driven undiagnosed diabetes poses unique dilemmas, because delayed diagnosis of diabetes and, as a result, delayed treatment could worsen clinical outcomes [25]. In addition, patients with diagnosed diabetes may not visit a few opened laboratories to monitor their clinical status [16], increasing concerns related to a problematic postponement of identification of critical conditions. For example, concern reported in the literature include delayed presentation in DKA of new-onset or existing T1D cases, that may leads to a potentially fatal situation [19].

4. Discussion

The issue of COVID-19 outbreak has resulted in an unprecedented global health crisis, challenging health systems’ preparedness and ability to cope with a pandemic response. Because of the unprecedented impact of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide, unfortunately, it is inevitable that this crisis will have a noticeable effect on routine healthcare services. Diabetes was the condition reported to be most influenced by the reduction in healthcare resources due to COVID-19 [29]. Beyond the risks that can be anticipated from the direct acquisition of the virus among patients with diabetes, interruption in provision of care may have a larger impact for the wider population of patients with diabetes. Besides, proper glycemic control is crucial for diabetic patients during public health problems such COVID-19 outbreak, because long-term hyperglycemic may not only develop with chronic complications but also may lead to life-threatening infections. Glycemic control has shown different clinical outcomes in patients with coexisting diabetes and COVID-19. For example, one study reported that glycemic control and high fasting blood sugar was worsened during the COVID-19 outbreak [30]. However, in some studies there were no worsening of glycemic control in patients with diabetes during COVID-19 [31]. Furthermore, some differences in age has been observed in this regard. For instance, Pla et al. reported a minor worsening in glycemic control during lockdown among older patients compared with the youngest ones [32]. Klonoff et al. pointed to higher probability of death among patients with hypoglycemia and suggested that patients with COVID-19 receive treatment promptly for their glycemic control improvement [33]. Thus, it is imperative that healthcare authorities and providers take action to mitigate the negative impact on diabetes care.

The overarching theme regarding the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine diabetes care was reduced access to necessary health services given the both limited activities of healthcare settings and delayed healthcare seeking behaviors. In the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, some patients’ perception of the healthcare settings such as hospitals and clinics has changed from a place of safety and shelter to one of danger and fear that may discourage them from seeking treatment for even the most serious medical conditions. Although there is scarcity of quantitative data regarding the effect of the pandemic on healthcare utilization of patients with diabetes, previous reports of other chronic conditions have indicated that declines in healthcare utilizations are widespread [34]. In the short term, diabetes care needs to be adapted to minimize infection exposure. Once such measures have been implemented successfully, it would be necessary to reassure that high-risk populations, such as patients with diabetes, are safe to seek medical advice. In this regards, keeping population trust in the healthcare system capacity to safely address essential healthcare needs and simultaneously to control COVID-19 exposure risk in healthcare settings is crucial to ensuring appropriate care-seeking behaviors [35].

It is suggested that healthcare providers should adjust their routine ways for triage, assess, and care for patients by using methods not requiring face-to-face visits, such as the use of telemedicine [36]. Digital technologies encompass a broad range of health service tools such as real-time inter-active audio/video communication between patients and healthcare providers and remote monitoring of patients’ data. On the other hand, many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries that constitute more than 80% of the worlds’ diabetic population, lacks the basis of telemedicine in order to education and treatment of diabetes [16]. In addition, many of those with diabetes are elderly and have little literacy in these low resource countries. They can’t afford to use new smartphones. Even if the smartphones were provided, they would have difficulty utilizing it [16].

This review showed that many of patients with diabetes may not be able to continue with their routine self-care behaviors, suggesting an increased incidence of complications with prolongations in the duration of the lockdown.

It is well recognized that diabetes care is not only about glucose levels. It is also about emotional well-being and mental health [37]. Since diabetes is a chronic condition acting as a predictor factor of worse prognosis, in addition to challenges they face in terms of routine healthcare, aroused concern in people with diabetes and their families is understandable [24]. This highlights the need for mental health access and support for patients with diabetes. Currently, there is inadequate evidence on management of diabetes-related anxiety or distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is, however, general and mixed evidence on initiatives to reduce diabetes related stress, most of which require face-to-face consults that seems to be unsuitable in the current circumstance.

Depending on baseline capacity and COVID-19 caseload, the pandemic forces heath systems to make difficult decisions to response COVID-19 direct demands, while maintaining essential routine healthcare delivery. In this regard, WHO suggested that health systems should identify essential healthcare services that will be prioritized in their efforts to maintain continuity of service delivery [35].

In reviewing what has been published on the topic of challenges of diabetes management during covi-19 crisis, we found two noticeable absences. First is the absence of quantitative information about the extent to which diabetes care provision as well as utilization has been impacted. The literature to date focuses almost exclusively on perceived barriers of authors. The other neglected issue in the literature reviewed is that of identifying barriers of diabetes management during the crisis area from perspectives of patients with diabetes.

4.1. Study strengths and limitation

To our knowledge, this is the first review study comprehensively explore the challenges diabetics patients faced in the middle of pandemic. Challenges identified here can be enlightening for all health systems. The main limitation of the study was our review has explored the literature up to 8th April 2020; however, the pandemic has continued up to now, and likely we have missed some potential published articles which could include new points. One of the main limitations of this study was our lack of access to certain databases, which we tried to resolve this problem with comprehensive searching in available databases and looking for inaccessible articles in different sources. On the other hand, since our review indicated the complications of diabetes including mental health as an understudied factor in the diabetic-related literature which is intensified due to pandemic limitations such as lockdown, further studies are suggested to be conducted on mental health of diabetic patients.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic presents an unprecedented challenge to healthcare delivery, and the impact on diabetes care has been immense. Diabetes management has been put under pressure due to lockdown of standard outpatient clinics, decreased inpatient capacity, staff shortage, medicine shortage, unaffordable medicine, delayed care seeking, limited self-care practice, transport difficulties, and undiagnosed cases/events. Further work is required to quantify these consequences and to develop solutions ensuring balancing public health and the needs of those infected during this COVID‐19 pandemic. Healthcare systems around the world should take note of these difficulties, monitor real-time essential services coverage levels, and be prepared to reduce the barriers to enable patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, to again access timely and quality routine healthcare services.

Authors’ contributions

MM, SAA and AM contributed to the concept and design of the study. ME, MF, SA, HM and FG contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. MM, SAA and AM contributed to the critical revision of the article and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Du Z., Wang L., Cauchemez S., Xu X., Wang X., Cowling B.J., et al. Risk for transportation of coronavirus disease from Wuhan to other cities in China. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020;26(5):1049. doi: 10.3201/eid2605.200146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T., Tian F., Jin D.-Y., Chen L., et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells C.R., Sah P., Moghadas S.M., Pandey A., Shoukat A., Wang Y., et al. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(13):7504–7509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002616117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. Coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (Accessed 13 August 2020).

- 6.Witt A., Ordóñez A., Martin A., Vitiello B., Fegert J.M. Springer; 2020. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service Provision and Research During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Challenges, Opportunities, and a Call for Submissions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elston J., Cartwright C., Ndumbi P., Wright J. The health impact of the 2014–15 Ebola outbreak. Public Health. 2017;143:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guariguata L., Whiting D.R., Hambleton I., Beagley J., Linnenkamp U., Shaw J.E. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014;103(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association AD Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015 abridged for primary care providers. Clin. Diabetes. 2015;33(2):97. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.33.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witko-Sarsat V., Rieu P., Descamps-Latscha B., Lesavre P., Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Neutrophils: molecules, functions and pathophysiological aspects. Lab. Investig. 2000;80(5):617–653. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mays N., Pope C., Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2005;10(Suppl. 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott E.S., Jenkins A.J., Fulcher G.R. Challenges of diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med. J. Aust. 2020;213(2):56–57. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn D.T. The COVID-19 pandemic: a “Tech”-tonic shift toward virtual diabetes care. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020;14(4):708–709. doi: 10.1177/1932296820929719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamble A., Pham Q., Goyal S., Cafazzo J.A. The challenges of COVID-19 for people living with diabetes: considerations for digital health. JMIR Diabetes. 2020;5(2) doi: 10.2196/19581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaly I., Iyengar K., Bahl S., Hughes T., Vaishya R. Redefining diabetic foot disease management service during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(5):833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nouhjah S., Jahanfar S. Challenges of diabetes care management in developing countries with a high incidence of COVID-19: a brief report. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(5):731–732. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rayman G., Lumb A., Kennon B., Cottrell C., Nagi D., Page E., et al. Guidelines for the management of diabetes services and patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Diabet. Med. 2020;37(7):1087–1089. doi: 10.1111/dme.14316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beran D., Aebischer Perone S., Castellsague Perolini M., Chappuis F., Chopard P., Haller D.M., et al. Beyond the virus: ensuring continuity of care for people with diabetes during COVID-19. Prim. Care Diabetes. 2020;15(1):16–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klatman E.L., Besancon S., Bahendeka S., Mayige M., Ogle G.D. COVID-19 and type 1 diabetes: challenges and actions. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bornstein S.R., Rubino F., Khunti K., Mingrone G., Hopkins D., Birkenfeld A.L., et al. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):546–550. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartmann-Boyce J., Morris E., Goyder C., Kinton J., Perring J., Nunan D., et al. Diabetes and COVID-19: risks, management, and learnings from other national disasters. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1695–1703. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo W., Li M., Dong Y., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Tian C., et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID‐19. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capaldo B., Annuzzi G., Creanza A., Giglio C., De Angelis R., Lupoli R., et al. Blood glucose control during lockdown for COVID-19: CGM metrics in Italian adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e88–89. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacques R.K., Renza S. The COVID19 pandemic–perspectives from people living with diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barone M.T.U., Harnik S.B., de Luca P.V., de Souza Lima B.L., Wieselberg R.J.P., Ngongo B., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on people with diabetes in Brazil. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pal R., Bhadada S.K. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: an unholy interaction of two pandemics. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh A., Arora B., Gupta R., Anoop S., Misra A. Effects of nationwide lockdown during COVID-19 epidemic on lifestyle and other medical issues of patients with type 2 diabetes in north India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(5):917–920. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maiya A.G., Gundmi S., Matpady P., Jadhav R., Lingadakai R., Hande M., et al. Prevalence of foot complications in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a community-based survey in rural Udupi. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds. 2018;17(3):169–175. doi: 10.1177/1534734618791853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chudasama Y.V., Gillies C.L., Zaccardi F., Coles B., Davies M.J., Seidu S., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on routine care for chronic diseases: a global survey of views from healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(5):965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue T., Li Q., Zhang Q., Lin W., Weng J., Li L., et al. 2020. Blood Glucose Levels in Elderly Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes During COVID-19 Outbreak: A Retrospective Study in a Single Center. Available at SSRN 3566198. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tornese G., Ceconi V., Monasta L., Carletti C., Faleschini E., Barbi E. Glycemic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus during COVID-19 quarantine and the role of in-home physical activity. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2020;22(6):462–467. doi: 10.1089/dia.2020.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pla B., Arranz A., Knott C., Sampedro M., Jiménez S., Hernando I., et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020;4(12) doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klonoff D.C., Messler J.C., Umpierrez G.E., Peng L., Booth R., Crowe J., et al. Association between achieving inpatient glycemic control and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a multicenter, retrospective hospital-based analysis. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):578–585. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mafham M.M., Spata E., Goldacre R., Gair D., Curnow P., Bray M., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):381–389. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Organization WH . World Health Organization; 2020. COVID-19: Operational Guidance for Maintaining Essential Health Services During an Outbreak: Interim Guidance, 25 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Outpatient and Ambulatory Care Settings: Responding to Community Transmission of COVID-19 in the United States.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ambulatory-care-settings.html [Updated 2020; cited]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young-Hyman D., De Groot M., Hill-Briggs F., Gonzalez J.S., Hood K., Peyrot M. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2126–2140. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]