Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the effectiveness and safety of baricitinib for severe COVID-19 in cytokine storm syndrome based on its potential role as an anti-inflammatory immunomodulator and inhibitor of viral endocytosis.

Methods

This was an observational retrospective study of hospitalised patients treated with baricitinib for severe COVID-19. Outcomes were clinical improvement on an ordinal scale of 1–8 on day 1 of baricitinib compared with day 14 (where 8=death and 1=not hospitalised with no limitations of activities), overall survival, time to recovery since baricitinib treatment started (days until hospital discharge) and laboratory parameters related to COVID-19 poor prognosis. Adverse events related to baricitinib during the admission period were also reported.

Results

Forty-three patients (70% men, mean age 70 years (IQR 54–79)) treated with baricitinib daily for 6 days (IQR 5–7) were included. Thirty-six patients were treated with corticosteroids (84%). Clinical improvement was 3 points (IQR 1–4) in patients on an ordinal scale of 4–6, overall survival was 100% at day 30 and day 60 with a mean time to recovery of 12 days (IQR 9–25) from start of baricitinib treatment. No adverse events of interest were found and all poor prognosis risk factors improved at day 14: interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, ferritin, lymphocytes, platelets and D-dimers.

Conclusions

Patients treated with baricitinib for severe COVID-19 showed improvements in clinical and analytical values without relevant adverse events and 100% overall survival. Clinical randomised trials are needed to confirm the clinical benefit of baricitinib.

Keywords: COVID-19, evidence-based medicine, pulmonary medicine, virology, critical care, education, pharmacy

Introduction

A novel coronavirus causing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) first emerged in Wuhan, China in December 2019 as the cause of a respiratory illness designated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). By 10 June 2021 COVID-19 had led to more than 174 061 995 cases and 3 758 560 deaths.1

Although most infections are self-limiting, about 15% of infected adults develop severe pneumonia. Older patients and those with pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular conditions are at greater risk for severe complications including severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ failure and death.2 Several therapeutic agents have been evaluated for the treatment of COVID-19 and its complications.3 Corticosteroids are the cornerstone of treatment of COVID-19,4 and tocilizumab has also been found to have clinical benefit.5 6 More limited improvement was observed with remdesivir in the early stage of treatment.7

Among the complications of COVID-19, cytokine storm is considered a major cause of multiple organ failure and ARDS.8 Therefore, effectively suppressing the cytokine storm is important to prevent severe COVID-19 complications and to reduce mortality.

Baricitinib is an immunomodulatory agent used for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in adults by means of a selective and reversible inhibition of Janus-associated kinases (JAKs) JAK1 and JAK2. JAKs are enzymes that transduce the signalling of a number of cytokines and growth factors involved in haematopoiesis, inflammation and immune function.9–11 These two kinases initiate signal transduction started by binding of interleukin (IL)-6 to its receptor and are also involved in signal transduction of other cytokines including tumour necrosis factor α and IL-10. They may therefore have a potential role in reducing systemic inflammation and lung damage. Baricitinib may also reduce receptor-mediated viral endocytosis by inhibiting AAK1 kinase.12 Based on the preclinical data, baricitinib has been used off-label as a COVID-19 treatment in hospitalised patients, but it is necessary to generate evidence in the context of clinical practice.

The hypothesis is that the use of baricitinib as an immunomodulatory treatment is associated with a lower risk of progression or death from severe COVID-19 and would improve the clinical and analytical results of patients without causing relevant adverse events. Therefore, the objective is to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of baricitinib for the treatment of severe COVID-19 in pretreated hospitalised patients during the first wave of the pandemic.

Methods

Design

This was an observational retrospective multidisciplinary study carried out at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Valencia, Spain. The inclusion period was between 15 March and 30 April 2020. All participants signed informed consent and ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the hospital. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation – Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the protocol is available online.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were the following: age ≥18 years, diagnosis of severe COVID-19 and treatment for at least 3 days with baricitinib. The institution created a protocol that defined severe COVID-19 as respiratory distress confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens with any of the following requirements: chest imaging with multilobe or bilateral infiltrate, >30 breaths/min, oxygen saturation ≤92% in ambient air or partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) <300. The following poor prognostic factors were also considered: lymphocytes <1000 cells/mm3, D-dimers >1000 ng/mL, C-reactive protein >100 mg/L, lactate dehydrogenase >300 UI/L or IL-6 >40 pg/mL.

Procedures

The suggested regimen was off-label use of oral baricitinib 4 mg daily for 5–7 days, according to Spanish regulations. Any other treatment or technique for COVID-19 and its complications was allowed.

The data obtained included age, gender, length of stay, medication administration data, historical and current medication lists, comorbidities, oxygen therapy, ventilatory support data and laboratory test results. Initial severity was assessed with classical pneumonia scores (Pneumonia Severity Index and CURB65 score).8 The analytical parameters measured were creatinine and parameters related to poor prognosis: IL-6, C-reactive protein, ferritin, lymphocytes, platelets and D-dimers. Data were collected from the hospital’s electronic prescription programme and electronic medical records, combining manual and automatic processing.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the clinical recovery on an 8-category ordinal scale used in other COVID-19 clinical trials. It was defined as the difference in clinical status by the 8-category ordinal scale in patients treated with baricitinib on day 1 compared with day 15. The categories are as follows: 1, not hospitalised, no limitations of activities; 2, not hospitalised, limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both; 3, hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen and no longer requiring ongoing medical care (used if hospitalisation was extended for infection control reasons); 4, hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen but requiring ongoing medical care (COVID-19-related or other medical conditions); 5, hospitalised, requiring any supplemental oxygen; 6, hospitalised, requiring non-invasive ventilation or use of high-flow oxygen devices; 7, hospitalised, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; and 8, death.

Time to recovery was defined as the day a patient reaches categories 1 or 2 on the 8-category ordinal scale since day 1. Overall survival rates at days 30 and 60 were also measured. Analytical improvement was measured as the difference in analytical values of poor prognostic factors at day 15.

Safety was measured as any adverse event collected from the information in the electronic medical records, such as upper respiratory tract infections, reactivation of latent infections (varicella zoster virus, tuberculosis, hepatitis B virus or Epstein–Barr virus), or if statistically significant increases in creatinine occurred at day 15.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for data that were not normally distributed and the Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables to assess the differences in means of the two groups. The graphical and statistical tests suggested that the proportional hazard assumption was not violated. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 25 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The significance for all statistical analyses was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

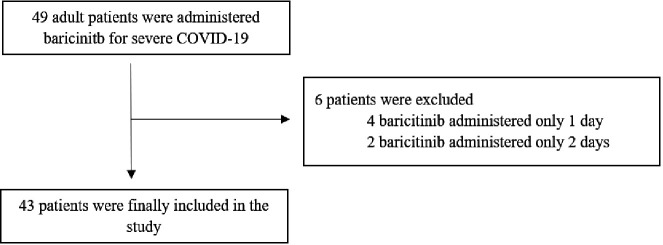

Of 49 patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the hospital during the study period and to whom baricitinib was prescribed, a total of six patients were excluded due to having received baricitinib for ≤2 days (figure 1). Four of the six patients received baricitinib for 1 day and two received it for 2 days. The reasons for discontinuation of baricitinib were as follows: three due to clinical improvement, two due to death and one due to initiation of palliative care with subsequent death. These three deaths were attributed to severe COVID-19 without being related to adverse events of baricitinib.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart

The distribution of the patients’ baseline characteristics on day 1 of treatment with baricitinib is shown in table 1 according to age group, gender, days of treatment with baricitinib, medication during admission, comorbidities, initial 8-category ordinal scale and laboratory tests at day 1 of baricitinib. Other specific treatments used in our cohort were chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine (98%), corticosteroids (84%), lopinavir/ritonavir (21%), tocilizumab (19%) and others (table 1). Tocilizumab was not administered concomitantly with baricitinib in any case.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients on day 1 of receiving baricitinib

| Characteristics | Patients Baricitinib (n=43) |

| Age, n | |

| <40 years | 3 (7%) |

| 40–59 years | 11 (26%) |

| 60–79 years | 19 (44%) |

| ≥80 years | 10 (23%) |

| Male gender, n | 30 (70%) |

| Comorbidities, n | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 19 (44%) |

| Hypertension | 22 (51%) |

| Heart disease | 12 (28%) |

| Diabetes | 11 (26%) |

| Respiratory disease | 6 (14%) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 2 (5%) |

| Cancer | 1 (2%) |

| Days of treatment with baricitinib, median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) |

| Initial 8-category ordinal scale, median (range)* | 6 (6–4) |

| 6. Hospitalised, receiving non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen devices | 23 (53%) |

| 5. Hospitalised, requiring supplemental oxygen | 12 (28%) |

| 4. Hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen, requiring ongoing medical care (COVID-19-related or otherwise) | 8 (19%) |

| 3. Hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen and no longer requiring ongoing medical care (used if hospitalisation was extended for infection control reasons) | 0 (0%) |

| 2. Not hospitalised, limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both | 0 (0%) |

| 1. Not hospitalised, no limitations of activities | 0 (0%) |

| Laboratory tests, median (IQR)† | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL; normal range 0.5–1.3) | 0.9 (0.74–1.04) |

| ≥1.3 | 4/43 (9%) |

| <1.3 | 39/43 (91%) |

| Interleukin (IL)-6 (pg/mL; normal range 0–0.7) | 53.0 (37.1–100.3) |

| ≥7.0 | 34/39 (87%) |

| <7.0 | 5/39 (13%) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL; normal range 0–5.0) | 89.8 (36.0–149.6) |

| ≥5.0 | 39/43 (91%) |

| <5.0 | 4/43 (9%) |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL; normal range 21.0–275.0) | 716.0 (334.3–1261.8) |

| ≥275.0 | 22/28 (79%) |

| <275.0 | 6/28 (21%) |

| Lymphocyte count (×10 L; normal range 1.1–3.2) | 1.09 (0.82–1.51) |

| ≥1.1 | 21/43 (49%) |

| <1.1 | 22/43 (51%) |

| Platelets (×109/L; normal range 100.0–350.0) | 266.0 (217.0–336.0) |

| ≥100 | 43/43 (100%) |

| <100 | 0/43 (0%) |

| D-dimer (µg/L; normal range 0.0–1.5) | 9.56 (4.5–16.9) |

| ≥1.5 | 42/43 (98%) |

| <1.5 | 1/43 (2%) |

| Medication during admission, n | |

| Azithromycin | 42 (98%) |

| Ceftriaxone | 36 (84%) |

| Other antibiotic agent | 19 (44%) |

| Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine | 42 (98%) |

| Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) | 37 (86%) |

| Corticosteroids | 36 (84%) |

| Tocilizumab | 8 (19%) |

| Convalescent plasma | 2 (5%) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 9 (21%) |

| Darunavir/cobicistat | 1 (2%) |

| Famciclovir | 1 (2%) |

| Colchicine | 1 (2%) |

Data are median (IQR), median (range), n (%) or n/N (%).

*Eight-category ordinal scale defined as follows: 1, not hospitalised, no limitations of activities; 2, not hospitalised, limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both; 3, hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen and no longer requiring ongoing medical care (used if hospitalisation was extended for infection control reasons); 4, hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen but requiring ongoing medical care (COVID-19-related or other medical conditions); 5, hospitalised, requiring any supplemental oxygen; 6, hospitalised, requiring non-invasive ventilation or use of high-flow oxygen devices; 7, hospitalised, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; and 8, death. It was measured on day 1 of administration of baricitinib.

†Initial laboratory tests were measured as the closest value to day 1 of baricitinib with a margin of 96 hours prior.

Study outcomes

Among the 43 patients included in the analysis, the median clinical improvement was 3 points (IQR 1–4) on the clinical scale (6 points (IQR 5–6) on day 1 vs 2 points (IQR 2–4) at day 15), which was a statistically significant difference (p<0.01). In table 2 the clinical improvement ratings from the perspective of the measured baseline score at day 1 are summarised. Twenty-six patients (60%) were discharged on day 15 of baricitinib treatment. Mean time to recovery was 12 days (IQR 9–25) from the start of baricitinib treatment and the overall survival was 100% at day 30 and at day 60 (all 43 patients were discharged from hospital due to clinical improvement). Seven (16%) patients required admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) during admission (three (43%) received baricitinib before the ICU admission and four (57%) started baricitinib on leaving the ICU) with a median length of stay of 13 days (IQR 11.5–18).

Table 2.

Outcomes overall and according to score on the ordinal scale

| Overall (n=43) |

Initial 8-category ordinal scale (n=43) |

|||

| 6 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Clinical improvement* | 3 (1–4), p<0.01† | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| Overall survival at the end of the study period | 43 (100) | 23 (53) | 12 (28) | 8 (19) |

| Time to recovery in days* | 12 (9–25) | 20 (14–31) | 18 (13–34) | 23 (15–29) |

| Bariciinib-related adverse events | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 8-category ordinal scale at day 14 | 3 (2–4) | 23 (53) | 12 (28) | 8 (19) |

| 1. Not hospitalised, no limitations of activities | 6 (14) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) |

| 2. Not hospitalised, limitation of activities, home oxygen requirement, or both | 20 (47) | 10 (23) | 7 (16) | 3 (7) |

| 3. Hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen and no longer requiring ongoing medical care (used if hospitalisation was extended for infection control reasons) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| 4. Hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen but requiring ongoing medical care (COVID-19-related or other medical conditions) | 8 (19) | 3 (7) | 4 (9) | 1 (2) |

| 5. Hospitalised, requiring any supplemental oxygen | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 6. Hospitalised, requiring non-invasive ventilation or use of high-flow oxygen devices | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 7. Hospitalised, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 8. Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Days of treatment with baricitinib | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5.5–6) | 6 (5–7) | 5.5 (5–6.5) |

Data are median (IQR) or n (%N).

*Clinical improvement was measured as the difference in the 8-category ordinal scale between day 14 and day 1 and time to recovery was defined as the day a patient reaches categories 1 or 2 on the 8-category ordinal scale since day 1.

†P values calculated with Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

All the analytical parameters related to poor prognosis of COVID-19 improved with statistically significant differences (p<0.05): IL-6, –50.7 pg/mL (IQR −19.0 to −97.6); PCR, −86.4 mg/L (IQR −24.1 to −144.1); ferritin −159.0 ng/mL (IQR −18.0 to −438.0); lymphocytes, +0.41×103/mm3 (IQR −0.09 to +1.11); platelets, +51.0×103/mm3 (IQR −57 to +168); and D-dimers −347 ng/mL (IQR −866 to +20).

With regard to safety, no adverse events of interest associated with baricitinib (eg, respiratory tract infections, reactivation of latent infections) or significant differences in creatinine values were found during the admission period.

Discussion

Baricitinib has been used off-label for COVID-19 since communications which proposed using it for its double mechanism of action—first as an immunomodulator interfering in the release of cytokines and second as an antiviral preventing the endocytosis of the virus by inhibition of AP2-associated protein kinase 1 (AAK1) and binding to cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK).

A retrospective non-randomised controlled study of 113 patients in the baricitinib arm with moderate COVID-1913 found a significantly lower mortality rate at 2 weeks, fewer ICU admissions and a higher discharge percentage at weeks 1 and 2 from the start of baricitinib treatment compared with the control group. A recent meta-analysis,14 including data from seven studies, estimated a significant decrease in the relative risk of death with baricitinib of 0.44 (0.31 to 0.63; p<0.001), which is in accordance with the results of our cohort.

However, the reasons for limiting the use of baricitinib have been based on its safety. Based on the experience of its use in the pathologies for which it is indicated, there is concern about the risk of developing reactivation of latent infections, further increasing the risk if we consider that patients with severe COVID-19 are mostly elderly and have a low lymphocyte count.15 16 Fortunately, the duration of baricitinib treatment that is proposed for COVID-19 is shorter than in rheumatologic diseases and there are case series that did not find any serious adverse events related to baricitinib.3 17 In fact, the patients in our study were mostly elderly, 51% had lymphopenia and none of them developed relevant adverse events related to baricitinib.

In addition, a published uncontrolled retrospective case series of the use of baricitinib for moderate and severe COVID-19 found that, of 15 patients with moderate to severe COVID-19, a short course of baricitinib in combination with hydroxychloroquine was tolerated and temporally associated with recovery in 12 of the 15 patients.18 A retrospective non-randomised controlled study found only seven adverse events (6%) which did not require discontinuation of treatment in 113 patients treated with baricitinib for moderate COVID-19.13

The RECOVERY study was a randomised clinical trial which compared a range of possible treatments with usual care in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 receiving oxygen without invasive mechanical ventilation.4 This study considered dexamethasone as the backbone of COVID-19 therapy, showing lower 28-day mortality among those who were receiving either invasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen alone, although no differences were observed in patients without respiratory support.

Remdesivir was recently authorised for use in COVID-19 because a benefits and risks balance was shown to be positive in patients requiring supplemental oxygen. The clinical trial considered variables similar to our study to measure clinical benefit.19 The randomised controlled trial included 158 patients who on day 1 had the following characteristics: 65% corticosteroid therapy, 18% patients were in group 6 (hospital admission, requiring high-flow nasal cannula or non-invasive mechanical ventilation) and 82% were in group 5 (hospital admission, requiring supplemental oxygen). In our study, at day 1 of baricitinib treatment patients were classified as group 6 (53%), group 5 (28%) and group 4 (19%). Group 4 patients had poor prognostic factors. Overall survival at day 28 was 86% in the remdesivir group and 100% in our cohort. At 14 days after remdesivir, 27% of patients had improved at least two points in the remdesivir group and 68% at 15 days in our patients. The combined use of remdesivir and baricitinib has recently been authorised for treating patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation based on a randomised controlled trial.20

Our study has some limitations. First, our cohort does not include controls, so it is not clear if the patients would have had these results without baricitinib. All patients received other treatments during admission, although only corticosteroids have shown a clinical benefit in COVID-194 21–23 and remdesivir in the early stage of treatment.7 In our cohort, no patient was treated with remdesivir, but 36 patients (84%) were treated with corticosteroids, making it difficult to separate both effects. Furthermore, 19% were also treated with tocilizumab, but simultaneously. Finally, some relevant covariables could inadvertently have not been included (such as PaO2/FIO2), probably related to the retrospective design.

In this study, patients treated with baricitinib for severe COVID-19 based on the established hospital therapeutic protocol showed statistically significant improvements in clinical outcomes and analytical parameters, with an overall survival rate of 100% and a median time to recovery of 12 days. Eighty-four patients were treated with concomitant corticosteroids during admission. Therefore, a synergistic response combining the inhibition of viral endocytosis of baricitinib and immunomodulation and the complementary anti-inflammatory effect that is achieved by combining corticosteroids and baricitinib could explain the promising results obtained. Future studies combining remdesivir and baricitinib could confirm the relevant role of this drug in patients with most severe COVID-19.

Conclusions

Patients treated with baricitinib for severe COVID-19 showed improvement in clinical recovery, time to recovery and full overall survival at day 30. All the measured analytical parameters related to the poor prognosis of COVID-19 improved and no relevant adverse events were found during hospital admission. The results of the ongoing clinical trials of baricitinib will consolidate its efficacy and safety in severe COVID-19 and its conditions of use.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject

Baricitinib could be used in severe COVID-19 based on its potential role as an anti-inflammatory, immunomodulator and inhibitor of viral endocytosis

Poor real-world data are available in pretreated hospitalised patients.

What this study adds

None of the 43 patients died despite their poor prognosis

Patients showed improvements in clinical and analytical values at 14 days

No adverse events associated with baricitinib occurred

The combination of baricitinib plus corticosteroid was found to be safe

Footnotes

Twitter: @Ruben_farma, @PalanquesTomas, @OctavioBallesta, @juanemegias, @joseluis_pa

Contributors: RIG, RM, TP and OBL designed and performed the study and wrote the paper, CBA, JEMV, EL-B and IF-N analysed and corrected the paper. RMV, JARI and JLPA reviewed the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The project was approved by the ethics committee for drug research of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic [web site]. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [Accessed 10 Jun 2021].

- 2. Helmy YA, Fawzy M, Elaswad A, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. J Clin Med 2020;9:1225. 10.3390/jcm9041225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang J, Xie B, Hashimoto K. Current status of potential therapeutic candidates for the COVID-19 crisis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:59–73. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:693–704. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramiro S, Mostard RLM, Magro-Checa C, et al. Historically controlled comparison of glucocorticoids with or without tocilizumab versus supportive care only in patients with COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome: results of the CHIC study. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1143–51. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6., Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, et al. , REMAP-CAP Investigators . Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1491–502. 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 - final report. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1813–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘cytokine storm’ in COVID-19. J Infect 2020;80:607–13. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. European Medicines Agency . Product information Baricitinib. London: European Medicines Agency/Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jorgensen SCJ, Tse CLY, Burry L, et al. Baricitinib: a review of pharmacology, safety, and emerging clinical experience in COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 2020;40:843–56. 10.1002/phar.2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, et al. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet 2020;395:e30–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seif F, Aazami H, Khoshmirsafa M, et al. Jak inhibition as a new treatment strategy for patients with COVID-19. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2020;181:467–75. 10.1159/000508247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daniela M, Massimo E, Di N. Retrospective, multicenter study on the impact of baricitinib in COVID-19 moderate pneumonia. J Infect 2020;81:647–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen C-X, Wang J-J, Li H, et al. JAK-inhibitors for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Leukemia 2021;14:1–5 10.1038/s41375-021-01266-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Favalli EG, Biggioggero M, Maioli G, Martina B, Gabriella M, et al. Baricitinib for COVID-19: a suitable treatment? Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:1012–3. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30262-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Praveen D, Puvvada RC, M VA. Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib is not an ideal option for management of COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020;55:105967. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cantini F, Niccoli L, Matarrese D, et al. Baricitinib therapy in COVID-19: a pilot study on safety and clinical impact. J Infect 2020;81:318–56. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abeer M, Alex E, Ashish M. Use of baricitinib in patients with moderate and severe COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72:1247–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020;395:1569–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021;384:795–807. 10.1056/NEJMoa2031994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:460–70. 10.1001/jama.2020.10044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J, et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2411–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deng L, Li C, Zeng Q, et al. Arbidol combined with LPV/r versus LPV/r alone against corona virus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study. J Infect 2020;81:e1–5. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.