Abstract

Background

We analyzed associations between immunodeficiency and cancer incidence in a nationwide cohort of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; PLWH) in South Africa.

Methods

We used data from the South African HIV Cancer Match Study built on HIV-related laboratory measurements from the National Health Laboratory Services and cancer records from the National Cancer Registry. We evaluated associations between time-updated CD4 cell count and cancer incidence rates using Cox proportional hazards models. We reported adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) over a grid of CD4 values and estimated the aHR per 100 CD4 cells/µL decrease.

Results

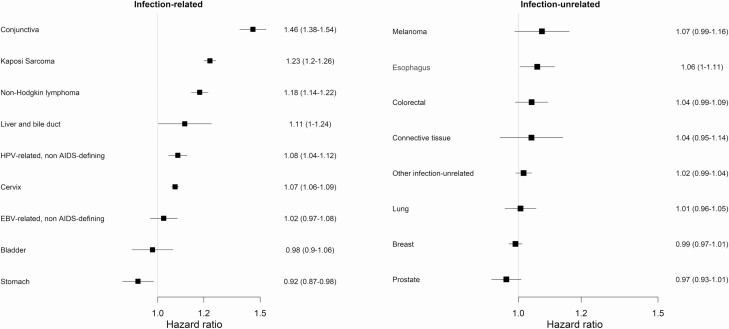

Of 3 532 266 PLWH, 15 078 developed cancer. The most common cancers were cervical cancer (4150 cases), Kaposi sarcoma (2262 cases), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (1060 cases). The association between lower CD4 cell count and higher cancer incidence rates was strongest for conjunctival cancer (aHR per 100 CD4 cells/µL decrease: 1.46; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.38–1.54), Kaposi sarcoma (aHR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.20–1.26), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (aHR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.14–1.22). Among infection-unrelated cancers, lower CD4 cell counts were associated with higher incidence rates of esophageal cancer (aHR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.00–1.11) but not breast, lung, or prostate cancer.

Conclusions

Lower CD4 cell counts were associated with an increased risk of developing various infection-related cancers among PLWH. Reducing HIV-induced immunodeficiency may be a potent cancer-prevention strategy among PLWH in sub-Saharan Africa, a region heavily burdened by cancers attributable to infections.

Keywords: HIV, cancer, immunodeficiency, CD4 cell count, South Africa

We studied the association between immunodeficiency and the incidence of various cancers in people living with human immunodeficiency virus in South Africa. Lower CD4 cell counts were associated with a higher risk of multiple types of infection-related cancers.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been classified as carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [1]. Yet, the mechanisms through which HIV infection increases cancer risk are not fully understood. HIV-induced immunodeficiency and coinfections with oncogenic viruses among people living with HIV (PLWH) are likely to play a key role [2, 3]. Evidence for direct pro-oncogenic effects of HIV, especially in lymphomagenesis, has also emerged [4].

Three infection-related cancers were found to occur particularly frequently among PLWH, namely Kaposi sarcoma (KS), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and cervical cancer. Therefore, these malignancies were included in the case definition of AIDS [5]. However, over time, it has become apparent that PLWH experience higher incidence rates of other non–AIDS-defining cancers, many of which are also infection related [6–8]. For example, PLWH are at increased risk of developing Hodgkin’s lymphoma (related to Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]), liver cancer (related to hepatitis B and C virus), stomach cancer (related to Helicobacter pylori), and anogenital cancers (related to human papillomavirus [HPV]) compared with the general population [1, 6–8]. Additionally, conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma is an emerging cancer among PLWH in Africa [9].

Immunodeficiency is a strong risk factor for developing KS and NHL [10, 11]. The KS and NHL incidence rates have steeply declined since antiretroviral therapy (ART) became widely available [12]. Advanced immunodeficiency has also been linked to increased rates of certain non–AIDS-defining cancers, such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma and liver, lung, and anal cancer among PLWH in the United States or Europe [10, 11]. Studies of non–AIDS-defining cancers in sub-Saharan Africa are often limited by small numbers of incident cases.

We used data from the South African HIV Cancer Match (SAM) Study to assess the association between lower CD4 cell counts and the risk of developing various cancer types among 3.5 million PLWH in South Africa.

METHODS

The SAM Study

The SAM study is a nationwide cohort of PLWH in South Africa and has been described in detail elsewhere [13]. Briefly, it is the result of a linkage between HIV-related laboratory records of the National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) and pathology-based cancer diagnoses from the National Cancer Registry (NCR) for the period 2004–2014. The NHLS is the largest diagnostic pathology service in South Africa and is estimated to cover approximately 80% of the South African population (https://www.nhls.ac.za). Privacy-preserving probabilistic record linkage methods were used to identify NHLS records from the same individual and to link them to cancer diagnoses from the NCR [14]. The study received ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (M190594), and the Cantonal Ethics committee in Bern (2016–00589).

Inclusion Criteria and Definitions

We included adults aged 18 years and older at cohort entry, with CD4 count measurements on separate days, and who had at least 1 year of follow-up after the date of their first CD4 count. Persons living with HIV entered the cohort at the time of the first HIV-related laboratory test (baseline). We excluded PLWH with missing information on sex or age. Individuals who were diagnosed with cancer before cohort entry were excluded from the analysis of that cancer.

We used the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), diagnoses to identify cancer types. We categorized cancers into infection-related and infection-unrelated cancers, including breast cancer (C50), colorectal cancer (C18–C20), cancer of the connective and soft tissue (C49), lung cancer (C34), melanoma of the skin (C43), esophageal cancer (C15), and prostate cancer (C61). Infection-related cancers were further classified according to the infectious agent they are typically associated with (Table 1) [8]. Of note, we categorized conjunctival cancer as infection related because HIV infection is an established risk factor [15]; however, to date, an association with other oncogenic viruses remains unclear. We excluded basal cell carcinoma (C44.0) and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin (C44.1) from all analyses.

Table 1.

Categorization of Infection-Related Cancers

| Infection | Cancer | ICD-10 Codes |

|---|---|---|

| AIDS-defining cancers | ||

| Human papillomavirus | Cervical | C53 |

| Human herpesvirus 8 | Kaposi sarcoma | C46 |

| Epstein-Barr virus | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | C82-C85 |

| Non–AIDS-defining cancers | ||

| Human papillomavirus | Anal | C21 |

| Head and neck | Variousa | |

| Penile | C60 | |

| Vaginal | C52 | |

| Vulvar | C51 | |

| Epstein-Barr virus | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | C81 |

| Nasopharyngeal | C11 | |

| HIVb | Conjunctival | C69.0 |

| Hepatitis B and C | Liver and bile duct | C22–24 |

| Helicobacter pylori | Stomach | C16 |

| Schistosomiasis | Bladder | C66, C67 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision.

aBase of tongue (C01), lingual tonsil (C02.4), palatine tonsil (C09.0–09.9), oropharynx (C10.2–10.9), pharynx NOS (C14.0), Waldeyer’s ring (C14.2).

bHIV infection is an established risk factor for conjunctival cancer but an association with other oncogenic viruses remains controversial.

Statistical Analysis

We produced descriptive statistics for PLWH with and without cancer. Age and calendar year were assessed at baseline. We defined time-at-risk as starting 1 year after the date of a patient’s first CD4 measurement. We right-censored patients 6 months after their last HIV-related laboratory measurement, at the database closing date (1 January 2015) or at the first diagnosis date of the cancer(s) under consideration, whichever came first. Thus, any patient with less than 1 year from the date of their first CD4 measurement to their right-censoring date was not included in the analysis. We analyzed associations between immunodeficiency (as indexed by time-updated CD4 count) and cancer incidence using proportional hazards (Cox) models separately for each cancer type/group. We time-updated CD4 counts at each measurement, carrying the value forward to the following CD4 measurement or censoring, whichever came first. We lagged the CD4 values by 1 year to minimize the risk of our results being affected by reverse causality—that is, we modeled cancer incidence as a function of the CD4 count from 1 year before. We modeled time-updated CD4 count as a continuous variable and produced adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) curves with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) over a grid of CD4 values, for a reference of 200 cells/µL. We modeled the relationship between CD4 count and the log-hazard using penalized spline bases with 3 degrees of freedom [16]. All models were adjusted for sex, age (continuous variable with penalized splines), calendar year (time-updated, categorical: 2004–2007, 2008–2011, 2012–2014), and comorbidity (yes/no, time-updated) from cancers not part of the outcome of interest. The calendar period categories were chosen to represent the changes in South African ART guidelines. In an additional analysis, we compared the relative strength of the CD4–cancer association across different cancers by estimating the aHR per 100 CD4 cells/µL decrease, assuming a linear relationship between CD4 count and the log-hazard. We performed this analysis including both sexes, and separately for men and women. We tested for interactions between sex and 100 CD4 count decrease. We assessed the Cox proportional hazards assumption using Schoenfeld residuals. We used the Akaike information criterion (AIC) to compare the model with penalized splines with the model without (ie, the linear model). All analyses were done in Stata 15 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and R 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Cancer Cases and Patient Characteristics

The SAM cohort provided data on 13 608 064 PLWH, of whom 3 532 266 were included in the overall cancer analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). A total of 27 954 adults were excluded from the analysis due to a prevalent cancer diagnosis (Supplementary Table 1). Among the included PLWH, 15 078 developed incident cancer over 9 108 565 person-years. The median time-at-risk was 2.1 years (interquartile range [IQR], .9–3.6 years) and the median number of CD4 measurements was 3 (IQR, 2–5). Among infection-related cancers, the most common types were cervical cancer (4150 cases), KS (2262 cases), and NHL (1060 cases). Non–AIDS-defining infection-related cancers were less common: there were 692 cases of non–AIDS-defining HPV-related cancers, 604 cases of conjunctival cancers, 288 cases of non–AIDS-defining EBV-related cancers, 164 cases of stomach cancers, 122 cases of bladder cancers, and 94 cases of liver and bile duct cancer.

There were 5182 patients diagnosed with an infection-unrelated cancer. The most common infection-unrelated cancer was breast cancer (1873 cases). There were 440 men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Lung cancer (415 cases), colorectal cancer (384 cases), esophageal cancer (370 cases), melanoma of the skin (151 cases), and connective and soft tissue tumors (107 cases) were less common. Excluding these 7 cancer types, there were 1537 patients diagnosed with other infection-unrelated cancers.

Tables 2 and 3 show the baseline characteristics of included PLWH, stratified by cancer type. Less than one-third of the total study population were male (28.6%). Still, most patients with stomach, bladder, lung, and esophageal cancer were male. The baseline median age was generally higher among PLWH with cancer compared with those remaining free of cancer, and ranged from 32.5 years for KS to 55.6 years for prostate cancer compared to 33.7 years in PLWH without cancer. The median CD4 count at baseline was lower in PLWH who developed cancer than those who did not, and ranged from 179 cells/µL in PLWH with conjunctival cancer to 291 cells/µL in PLWH with breast cancer compared to 292 cells/µL in PLWH who were free of cancer. A summary of age and calendar year at cancer diagnosis is shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics at the Baseline Test, Stratified by the Type of Diagnosed Cancer and Infection Group

| AIDS-Defining Cancers | Non–AIDS-Defining Cancers | Free of Cancer | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaposi Sarcoma | Cervical Cancer | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | HPV Relateda | Epstein-Barr Virus Relatedb | Conjunctival Cancer | Liver and Bile Duct Cancer | Stomach Cancer | Bladder Cancer | Infection Unrelated (See Table 3) | ||

| n | 2262 | 4150 | 1060 | 692 | 288 | 604 | 94 | 164 | 112 | 5182 | 3 517 188 |

| Female | 1256 (55.5) | 4150 (100.0) | 621 (58.6) | 487 (70.4) | 152 (52.8) | 402 (66.6) | 47 (50.0) | 77 (47.0) | 49 (43.8) | 3381 (65.2) | 2 509 847 (71.4) |

| Median [IQR] age, years | 32.51 [27.37, 38.52] | 38.62 [32.73, 45.77] | 36.19 [30.25, 42.96] | 36.64 [30.63, 45.10] | 33.56 [28.04, 39.27] | 35.14 [30.47, 40.80] | 44.26 [35.02, 51.36] | 45.04 [37.99, 53.86] | 50.15 [41.24, 57.21] | 44.79 [36.16, 52.68] | 33.65 [27.55, 41.17] |

| Calendar period | |||||||||||

| 2004–2007 | 1116 (49.3) | 1932 (46.6) | 511 (48.2) | 313 (45.2) | 150 (52.1) | 280 (46.4) | 42 (44.7) | 68 (41.5) | 46 (41.1) | 2388 (46.1) | 744 684 (21.2) |

| 2008–2011 | 1025 (45.3) | 1988 (47.9) | 491 (46.3) | 330 (47.7) | 122 (42.4) | 287 (47.5) | 49 (52.1) | 85 (51.8) | 57 (50.9) | 2491 (48.1) | 1 999 166 (56.8) |

| 2012–2014 | 121 (5.3) | 230 (5.5) | 58 (5.5) | 49 (7.1) | 16 (5.6) | 37 (6.1) | 3 (3.2) | 11 (6.7) | 9 (8.0) | 303 (5.8) | 773 338 (22.0) |

| Median [IQR] CD4 cell count (cells/µL) | 256 [137, 389] | 263 [139, 420] | 221 [112, 355] | 200 [105, 348] | 253 [150, 422] | 179 [87, 302] | 219 [128, 380] | 263 [155, 464] | 289 [151, 425] | 264 [139, 422] | 292 [164, 453] |

| CD4 cell count (cells/µL) | |||||||||||

| <50 | 168 (7.4) | 267 (6.4) | 81 (7.6) | 58 (8.4) | 15 (5.2) | 60 (9.9) | 10 (10.6) | 16 (9.8) | 8 (7.1) | 327 (6.3) | 198 893 (5.7) |

| 50–99 | 184 (8.1) | 336 (8.1) | 121 (11.4) | 84 (12.1) | 23 (8.0) | 94 (15.6) | 4 (4.3) | 10 (6.1) | 5 (4.5) | 412 (8.0) | 237 854 (6.8) |

| 100–199 | 386 (17.1) | 740 (17.8) | 226 (21.3) | 156 (22.5) | 50 (17.4) | 136 (22.5) | 22 (23.4) | 25 (15.2) | 22 (19.6) | 961 (18.5) | 585 063 (16.6) |

| 200–349 | 633 (28.0) | 1011 (24.4) | 258 (24.3) | 150 (21.7) | 73 (25.3) | 143 (23.7) | 24 (25.5) | 42 (25.6) | 27 (24.1) | 1257 (24.3) | 906 471 (25.8) |

| 350–499 | 355 (15.7) | 630 (15.2) | 134 (12.6) | 81 (11.7) | 45 (15.6) | 61 (10.1) | 12 (12.8) | 20 (12.2) | 20 (17.9) | 788 (15.2) | 631 328 (17.9) |

| 500–699 | 178 (7.9) | 400 (9.6) | 67 (6.3) | 39 (5.6) | 30 (10.4) | 28 (4.6) | 12 (12.8) | 23 (14.0) | 12 (10.7) | 489 (9.4) | 409 079 (11.6) |

| ≥700 | 79 (3.5) | 208 (5.0) | 40 (3.8) | 28 (4.0) | 12 (4.2) | 9 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (5.5) | 4 (3.6) | 281 (5.4) | 227 228 (6.5) |

| Missing | 279 (12.3) | 558 (13.4) | 133 (12.5) | 96 (13.9) | 40 (13.9) | 73 (12.1) | 9 (9.6) | 19 (11.6) | 14 (12.5) | 667 (12.9) | 321 272 (9.1) |

Data are presented as n or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; IQR, interquartile range.

aAnal, head and neck, penile, vaginal, vulvar cancer.

bHodgkin’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal cancer.

Table 3.

Patient Characteristics at the Baseline Test, Stratified by Infection-Unrelated Cancer Diagnosis

| Breast Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | Connective Tissue Cancer | Lung Cancer | Melanoma | Esophageal Cancer | Prostate Cancer | Other Infection-Unrelated Cancersa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1873 | 384 | 107 | 415 | 151 | 370 | 440 | 1537 |

| Female | 1850 (98.8) | 223 (58.1) | 59 (55.1) | 117 (28.2) | 89 (58.9) | 166 (44.9) | 0 (0.0) | 923 (60.1) |

| Median [IQR] age, years | 41.10 [34.18, 48.61] | 45.18 [36.16, 53.18] | 39.01 [31.22, 48.80] | 49.19 [43.56, 55.11] | 45.45 [37.55, 53.37] | 48.99 [42.59, 55.13] | 55.58 [50.46, 60.26] | 43.53 [34.39, 51.70] |

| Calendar period | ||||||||

| 2004–2007 | 896 (47.8) | 159 (41.4) | 55 (51.4) | 183 (44.1) | 67 (44.4) | 175 (47.3) | 173 (39.3) | 726 (47.2) |

| 2008–2011 | 886 (47.3) | 194 (50.5) | 47 (43.9) | 198 (47.7) | 77 (51.0) | 173 (46.8) | 235 (53.4) | 721 (46.9) |

| 2012–2014 | 91 (4.9) | 31 (8.1) | 5 (4.7) | 34 (8.2) | 7 (4.6) | 22 (5.9) | 32 (7.3) | 90 (5.9) |

| Median [IQR] CD4 cell count (cells/µL) | 291 [165, 452] | 259 [155, 385] | 248 [105, 430] | 238 [124, 405] | 233 [133, 374] | 244 [121, 387] | 244 [129, 401] | 251 [131, 410] |

| CD4 cell count (cells/µL) | ||||||||

| <50 | 115 (6.1) | 24 (6.2) | 8 (7.5) | 27 (6.5) | 12 (7.9) | 19 (5.1) | 27 (6.1) | 102 (6.6) |

| 50–99 | 118 (6.3) | 19 (4.9) | 14 (13.1) | 36 (8.7) | 12 (7.9) | 43 (11.6) | 39 (8.9) | 137 (8.9) |

| 100–199 | 287 (15.3) | 75 (19.5) | 21 (19.6) | 88 (21.2) | 32 (21.2) | 73 (19.7) | 84 (19.1) | 316 (20.6) |

| 200–349 | 483 (25.8) | 111 (28.9) | 18 (16.8) | 100 (24.1) | 37 (24.5) | 90 (24.3) | 104 (23.6) | 345 (22.4) |

| 350–499 | 323 (17.2) | 56 (14.6) | 15 (14.0) | 52 (12.5) | 20 (13.2) | 50 (13.5) | 64 (14.5) | 215 (14.0) |

| 500–699 | 187 (10.0) | 34 (8.9) | 11 (10.3) | 37 (8.9) | 9 (6.0) | 34 (9.2) | 42 (9.5) | 147 (9.6) |

| ≥700 | 124 (6.6) | 10 (2.6) | 7 (6.5) | 23 (5.5) | 10 (6.6) | 11 (3.0) | 20 (4.5) | 81 (5.3) |

| Missing | 236 (12.6) | 55 (14.3) | 13 (12.1) | 52 (12.5) | 19 (12.6) | 50 (13.5) | 60 (13.6) | 194 (12.6) |

Data are presented as n or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

aIncludes all infection-unrelated cancers not shown in the other columns.

Immunodeficiency and Cancer Incidence

Across all cancers, the penalized spline approach yielded lower or similar AIC values compared with linear models, indicating better fit to the data (Supplementary Table 4). Thus, we chose this approach for our primary analysis.

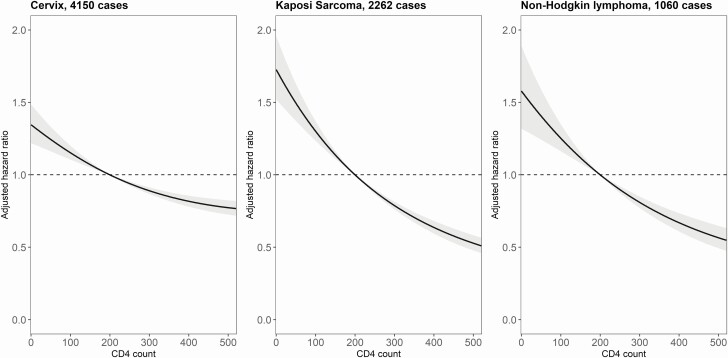

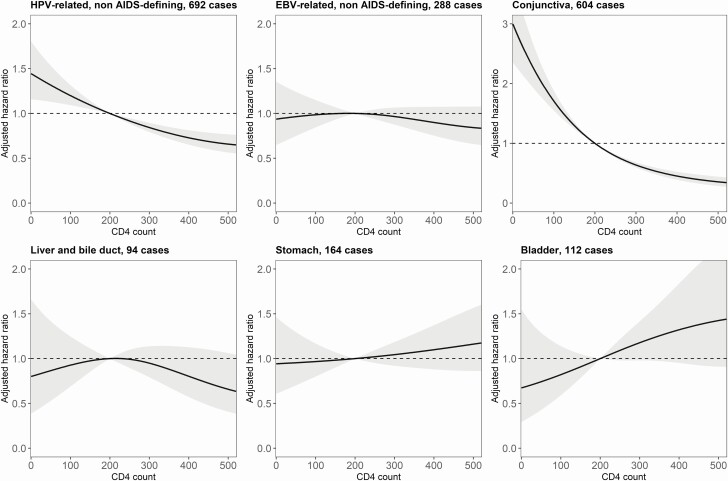

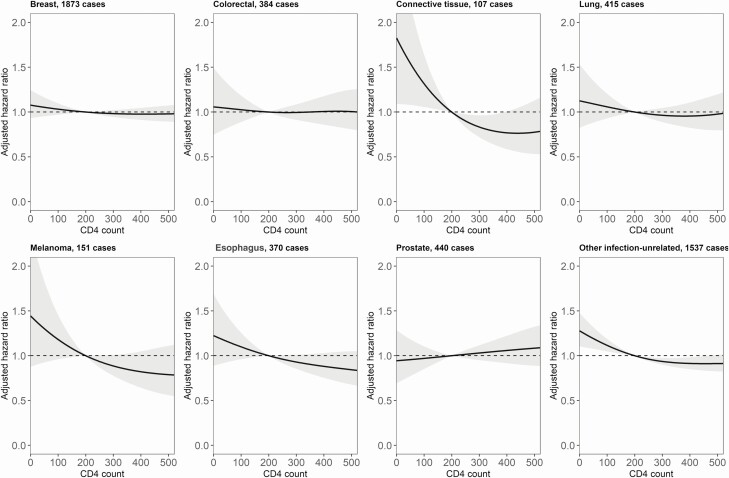

From visual inspection of results, lower CD4 counts were associated with higher incidence rates of the 3 AIDS-defining cancers (Figure 1), the non–AIDS-defining HPV-related cancers, and conjunctival cancer (Figure 2), but not with higher rates of liver, stomach, or bladder cancer. There was no evidence of an association between lower CD4 counts and higher incidence of non–AIDS-defining EBV-related cancers (Hodgkin’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal cancer). Among infection-unrelated cancers, we found an association between lower CD4 counts and higher incidence of connective and soft tissue cancer (Figure 3). There was also limited evidence of an association with esophageal cancer and melanoma of the skin.

Figure 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios (solid lines) with 95% confidence intervals (gray area) for the incidence of AIDS-defining cancers, comparing a grid of CD4 cell counts with the reference value of 200 cells/µL. The models are adjusted for sex, age, calendar year, and diagnosis of other cancers.

Figure 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios (solid lines) with 95% confidence intervals (gray area) for the incidence of infection-related, non–AIDS-defining cancers, comparing a grid of CD4 cell counts with the reference value of 200 cells/µL. The models are adjusted for sex, age, calendar year, and diagnosis of other cancers. Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Figure 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios (solid lines) with 95% confidence intervals (gray area) for the incidence of infection-unrelated cancers, comparing a grid of CD4 cell counts with the reference value of 200 cells/µL. The models are adjusted for sex, age, calendar year, and diagnosis of other cancers.

When assuming a linear relationship between CD4 count and the log-hazard, we found that, among infection-related cancers, the association with CD4 count (aHR per 100 CD4 cells/µL decrease) was strongest for conjunctival cancer, followed by KS and NHL (Figure 4). Moreover, there was evidence for a weak protective effect of a lower CD4 count against stomach cancer (aHR per 100 CD4 cells/µL decrease, .92; 95% CI, .87–.98). Among infection-unrelated cancers, the association between a lower CD4 count and cancer incidence was strongest for melanoma of the skin and esophageal cancer. Sex modified the association between CD4 count and cancer incidence for NHL (P = .006) and KS (P = .005), with the association being more substantial in women than men (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios for cancer incidence with associated 95% confidence intervals, per 100 cells/µL decrease in CD4 cell count. The models assumed a linear relationship between CD4 cell count and the log-hazard of the cancer, while adjusting for sex, age, calendar year, and diagnosis of other cancers. The cancers are ranked in decreasing order of their adjusted hazard ratios. Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HPV, human papillomavirus.

Discussion

Advanced immunodeficiency is associated with an increased risk of developing AIDS-defining cancers and various non–AIDS-defining infection-related cancers among a nationwide cohort of PLWH in South Africa. The association between lower CD4 counts and higher cancer incidence rates was strong for conjunctival cancer, KS, NHL, and cervical and other HPV-related cancers. We did not find an association between lower CD4 counts and higher rates of cancers related to nonviral infections (ie, stomach [H. pylori] and bladder cancer [schistosomiasis]) and common infection-unrelated cancers including breast, lung, and prostate cancer. The association between lower CD4 counts and cancer incidence tended to be stronger in women than men for KS and NHL.

Since the start of the HIV epidemic, many studies have explored the relationship between immunodeficiency and the incidence of infection-related cancers. In line with these, we found a clear association between lower CD4 counts and increased rates of AIDS-defining cancers—that is, KS [10, 11, 17, 18], NHL [10, 11, 19, 20], and cervical cancer [10, 21]. We and others [10, 11, 22, 23] also observed higher incidence rates of non–AIDS-defining HPV-related cancers such as anal [10, 22], vaginal/vulvar [24], and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [23] at lower CD4 counts. In our study, we assessed time-updated CD4 counts lagged by 1 year, whereas others identified nadir and cumulative CD4 count as well as CD4 count lagged by several years to be stronger predictors for the risk of developing HPV-related cancers [10, 22, 23]. Immunodeficiency may promote HPV-related carcinogenesis early on by increasing the risk of HPV acquisition and reducing HPV clearance [25]. Our findings only partially confirm an increased liver cancer risk in PLWH with advanced immunodeficiency [10, 11, 26]. Conjunctival cancer is particularly common in Africa and has been linked to ultraviolet radiation and HIV infection [9]. Our results corroborate an important role of immunodeficiency in the development of this cancer. Studies from the United States and Europe identified a clear association between lower recent CD4 counts and high Hodgkin’s lymphoma incidence rates [10, 11, 27]. However, we did not find such a trend for EBV-related non–AIDS-defining cancers (Hodgkin’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal cancer). Misdiagnosis of HIV-associated lymphomas as tuberculosis (TB) is common in resource-limited settings with high TB prevalence [28], and this may have distorted the estimated association between immunodeficiency and Hodgkin’s lymphoma risk. Of note, the association between CD4 counts and NHL risk in our study was also weaker than what has been described for North America and Europe [10, 11, 19]. Literature on the link between immunodeficiency and the risk of bladder and stomach cancers is scarce. An American study found a higher risk of developing non-cardia stomach cancer among PLWH with nadir CD4 counts of 200 cells/µL or less versus more than 200 cells/µL [29]. We did not find an association between lower CD4 counts and either bladder or stomach cancer incidence.

The association of lower CD4 counts with a KS and NHL risk was stronger among women than men. Most studies to date have not assessed whether the association between immunodeficiency and cancer risk is modified by sex. However, sex differences in cancer susceptibility have been reported consistently, with most cancers occurring more frequently in men [30]. Sex differences in immune surveillance, with women generally mounting stronger immune responses, may contribute to differences in cancer susceptibility between male and female PLWH [31].

Few studies have assessed the association between HIV-induced immunodeficiency and infection-unrelated cancers, and data from Africa are generally not available. In the United States, both breast and prostate cancer occur less frequently among PLWH than in the general population [32, 33], with prostate cancer risk being reduced among men with lower CD4 counts at AIDS diagnosis [34]. However, we did not find an association between lower CD4 counts and either prostate or breast cancer incidence. In our study, there was some evidence for higher incidence rates at lower CD4 counts for esophageal cancer as well as connective and soft tissue tumors. One study also found a higher risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma among PLWH with lower nadir CD4, but the uncertainty was considerable [29]. The association between lower CD4 counts and the risk of connective and soft tissue tumors is in line with case reports suggesting an etiological role of EBV in the development of leiomyosarcomas and leiomyomas [35]. However, it could also be a spurious finding if some KS cases were misclassified as other soft tissue sarcomas. For malignant melanoma of the skin, we found a weak association with lower CD4 counts, but previous studies showed conflicting results [11, 36]. The observation that some cancers currently categorized as infection-unrelated showed an association with lower CD4 counts could indicate that an unknown infectious cause may contribute to the development of these cancers.

This is the first large-scale study to explore associations between lower CD4 cell counts and various cancer types in sub-Saharan Africa. Our analysis included CD4 trajectories of 3.5 million PLWH over 9 million person-years. Our study has several limitations. Given that our cohort study was based on routine data, CD4 cell count measurements did not necessarily occur at regular intervals and we did not have access to ART data. However, we adjusted for calendar period, with breakpoints chosen to match changes in South African ART guidelines. Information on cancer risk factors such as coinfections with other oncogenic viruses, lifestyle factors, or socioeconomic status was also unavailable. The database closing date was 1 January 2015, but we do not expect immunodeficiency to influence cancer risk differently over time. The SAM study did not include mortality or emigration data. Thus, we censored patients 6 months after the last laboratory measurement. While this limits the amount of follow-up data in our study, we do not expect it to have biased our results. CD4 count is a commonly studied biomarker. Still, CD8 count, CD4-to-CD8 ratio, or RNA viral load are also important biomarkers for some cancers [10, 37, 38]. The NHLS does not routinely assess CD8 counts, and RNA viral loads were not reported frequently enough to create reliable trajectories.

Close to 30% of cancers in sub-Saharan Africa are infection related [15]. Among PLWH, the proportion of cancers attributable to infections is particularly high, with a proportion of 40% estimated in the United States [8]. In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of infection-related cancers among PLWH is likely to be even higher. Reducing immunodeficiency through early detection of HIV and effective ART has been key in decreasing KS and NHL incidence among PLWH worldwide [12, 39], and evidence is accumulating that timely initiation of ART might reduce the risk of developing cervical and anal cancers [40, 41]. However, it is less clear whether reducing HIV-induced immunodeficiency has a preventive effect on other cancers. We have shown that lower CD4 counts are associated with higher rates of various infection-related and infection-unrelated cancers among PLWH in South Africa. Therefore, preventing HIV-induced immunodeficiency may be an important strategy to reduce the disproportionate cancer burden among PLWH in sub-Saharan Africa. As the effect of immunodeficiency on carcinogenesis varies by cancer types, in-depth cancer-specific analyses are required. The SAM study, with its nationwide cohort of PLWH, provides an ideal platform for such analyses.

In conclusion, lower CD4 counts are associated with an increased risk of developing various infection-related cancers among PLWH. Reducing HIV-induced immunodeficiency may be a potent cancer-prevention strategy among PLWH in sub-Saharan Africa, a region heavily burdened by cancers attributable to infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Calculations were performed on UBELIX (http://www.id.unibe.ch/hpc), the high performance computing cluster at the University of Bern.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number U01AI069924. It was also supported by the NIH administrative supplement to Existing NIH Grants and Cooperative Agreements (Parent Administrative Supplement; U01AI069924-09; to M. E. and J. B.), the PEPFAR supplement (to M. E.), the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF; 320030_169967; to J. B. and M. E.), and the US CRDF Global (HIV_DAA3-16-62705-1; to M. M.). M. E. was supported by special project funding (17481) O. E. was supported by project grant number 180083. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme grant agreement number 801076, through the SSPH+ Global PhD Fellowship Program in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Biological agents. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, no. 100B. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dubrow R, Silverberg MJ, Park LS, Crothers K, Justice AC. HIV infection, aging, and immune function: implications for cancer risk and prevention. Curr Opin Oncol 2012; 24:506–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. da Silva Neto MM, Brites C, Borges ÁH. Cancer during HIV infection. APMIS 2020; 128:121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dolcetti R, Gloghini A, Caruso A, Carbone A. A lymphomagenic role for HIV beyond immune suppression? Blood 2016; 127:1403–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castro KG, Ward JW, Slutsker L, et al. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17:802–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shiels MS, Cole SR, Kirk GD, Poole C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52:611–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2007; 370:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Martel C, Shiels MS, Franceschi S, et al. Cancers attributable to infections among adults with HIV in the United States. AIDS 2015; 29:2173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hämmerl L, Ferlay J, Borok M, Carrilho C, Parkin DM. The burden of squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva in Africa. Cancer Epidemiol 2019; 61:150–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guiguet M, Boué F, Cadranel J, Lang JM, Rosenthal E, Costagliola D; Clinical Epidemiology Group of the FHDH-ANRS CO4 Cohort . Effect of immunodeficiency, HIV viral load, and antiretroviral therapy on the risk of individual malignancies (FHDH-ANRS CO4): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10:1152–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Silverberg MJ, Chao C, Leyden WA, et al. HIV infection, immunodeficiency, viral replication, and the risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20:2551–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980–2002. AIDS 2006; 20:1645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muchengeti M, Bartels L, Olago V, et al. Cohort profile: the South African HIV Cancer Ma tch Study (SAM). OSF Preprints [Preprint]. August 11, 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 12]. Available from: 10.31219/osf.io/w52sb. Accessed 11 February 2021. [DOI]

- 14. Schmidlin K, Clough-Gorr KM, Spoerri A; SNC Study Group . Privacy preserving probabilistic record linkage (P3RL): a novel method for linking existing health-related data and maintaining participant confidentiality. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015; 15:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parkin DM, Hämmerl L, Ferlay J, Kantelhardt EJ. Cancer in Africa 2018: the role of infections. Int J Cancer 2020; 146:2089–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eilers PHC, Marx BD.. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and Penalties. Statistical Science, 1996; 11:89–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bohlius J, Valeri F, Maskew M, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV-infected patients in South Africa: multicohort study in the antiretroviral therapy era. Int J Cancer 2014; 135:2644–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rohner E, Bütikofer L, Schmidlin K, et al. ; Comparison of Kaposi sarcoma risk in human immunodeficiency virus-positive adults across 5 continents: a multiregional multicohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1316–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hernández-Ramírez RU, Qin L, Lin H, et al. ; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS . Association of immunosuppression and HIV viraemia with non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk overall and by subtype in people living with HIV in Canada and the USA: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Costagliola D, et al. Incidence and risk factors of HIV-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: a European multicohort study. Antivir Ther 2009; 14:1065–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abraham AG, Strickler HD, D’Souza G. Invasive cervical cancer risk among HIV-infected women is a function of CD4 count and screening. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63:e163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hernández-Ramírez RU, Qin L, Lin H, et al. ; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS . Association of immunosuppression and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) viremia with anal cancer risk in persons living with HIV in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:1176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beachler DC, Abraham AG, Silverberg MJ, et al. ; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA . Incidence and risk factors of HPV-related and HPV-unrelated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in HIV-infected individuals. Oral Oncol 2014; 50:1169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chaturvedi AK, Madeleine MM, Biggar RJ, Engels EA. Risk of human papillomavirus-associated cancers among persons with AIDS. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101:1120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Looker KJ, Rönn MM, Brock PM, et al. Evidence of synergistic relationships between HIV and human papillomavirus (HPV): systematic reviews and meta-analyses of longitudinal studies of HPV acquisition and clearance by HIV status, and of HIV acquisition by HPV status. J Int AIDS Soc 2018; 21:e25110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clifford GM, Rickenbach M, Polesel J, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort . Influence of HIV-related immunodeficiency on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. AIDS 2008; 22:2135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clifford GM, Rickenbach M, Lise M, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study . Hodgkin lymphoma in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Blood 2009; 113:5737–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buyego P, Nakiyingi L, Ddungu H, et al. Possible misdiagnosis of HIV associated lymphoma as tuberculosis among patients attending Uganda Cancer Institute. AIDS Res Ther 2017; 14:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thrift AP, Kramer JR, Hartman CM, et al. Risk and predictors of esophageal and stomach cancers in HIV-infected veterans: a matched cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 81:e65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tevfik Dorak M, Karpuzoglu E. Gender differences in cancer susceptibility: an inadequately addressed issue. Front Genet 2012; 3:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:626–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coghill AE, Engels EA, Schymura MJ, Mahale P, Shiels MS. Risk of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer diagnoses among HIV-infected individuals in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018; 110:959–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robbins HA, Pfeiffer RM, Shiels MS, Li J, Hall HI, Engels EA. Excess cancers among HIV-infected people in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107:dju503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shiels MS, Goedert JJ, Moore RD, Platz EA, Engels EA. Reduced risk of prostate cancer in U.S. men with AIDS. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19:2910–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bhatia K, Shiels MS, Berg A, Engels EA. Sarcomas other than Kaposi sarcoma occurring in immunodeficiency: interpretations from a systematic literature review. Curr Opin Oncol 2012; 24:537–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yanik EL, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Qin L, et al. Brief report: cutaneous melanoma risk among people with HIV in the United States and Canada. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 78:499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clifford GM, Franceschi S, Keiser O, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study . Immunodeficiency and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3 and cervical cancer: a nested case-control study in the Swiss HIV cohort study. Int J Cancer 2016; 138:1732–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sigel K, Wisnivesky J, Crothers K, et al. Immunological and infectious risk factors for lung cancer in US veterans with HIV: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet HIV 2017; 4:e67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grulich AE, Vajdic CM. The epidemiology of cancers in human immunodeficiency virus infection and after organ transplantation. Semin Oncol 2015; 42:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kelly H, Weiss HA, Benavente Y, de Sanjose S, Mayaud P; ART and HPV Review Group . Association of antiretroviral therapy with high-risk human papillomavirus, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and invasive cervical cancer in women living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2018; 5:e45–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kelly H, Chikandiwa A, Alemany Vilches L, Palefsky JM, de Sanjose S, Mayaud P. Association of antiretroviral therapy with anal high-risk human papillomavirus, anal intraepithelial neoplasia, and anal cancer in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e262–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.