Abstract

The cytokine storm syndrome has been suggested as a mechanism in the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; COVID-19 [coronavirus disease 2019]) infection. Drugs such as tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 antagonist, have shown good results in other scenarios of hyperinflammatory state and might also be effective in COVID-19 disease. However, the best dosing regimen and the timing of infusion is currently unknown, specifically in obese patients. We report the first cases of tocilizumab administration in obese patients during the first days of COVID-19 worsening hypoxemia. This infusion was not adjusted by weight, following the manufacturer maximal dose limit. We kept a strict monitoring for possible infections, prior and during the treatment. All patients showed good improvements on chest-computed tomography images and oxygenation and were discharged from hospital shortly after, without complications or intubation. This case series highlights that tocilizumab seems to be effective to treat hyperinflammation of critical COVID-19 obese patients, even when the infusion of the ideal dose is not feasible to be administered. It also shows the importance of early timing in the decision to treat and the relevance of infections exclusion prior to the induction of immunosuppression by tocilizumab.

Keywords: obesity, tocilizumab, COVID-19, critical care, case report

Introduction

Infection with the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; COVID-19 [coronavirus disease 2019]) has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020. 1 Since its first description, in December 2019, in Wuhan, China, more than 3 982 500 deaths have been reported, with a mortality rate of about 2.16% worldwide. 2 Among multiple risk factors for worse outcomes and death, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes have been described in a recent series, 3 as related to higher severity of respiratory disease and complications.

Because of its complex pathophysiology and clinical course, with a cytokine storm syndrome 4 as well as a prothrombotic state 5 being described, multiple algorithms and therapeutic strategies have been proposed. Treatments that antagonize the uncontrolled cytokine release status, by blocking the interleukin activity, seem to have a theoretical role in COVID-19 disease. 6 This proposed mechanism of action proved to be effective in other conditions with severe cytokine storm, such as those seen in chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy 7 used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia. However, the lack of well-established benefit, with potentially fatal adverse effects, put some of these treatments into question alongside the bedside clinician evidence-based decision-making ability in a highly stressful environment. 8

One of these therapies uses a recombinant monoclonal antibody that acts as an interleukin-6 antagonist. Based on its mechanism of action, 9 this drug may act in severe cases of COVID-19 hyperinflammatory state and showed benefit in outcomes in a Chinese cohort, 10 with a good safety profile.

The optimal treatment regimen in the obese, as well as its effect in outcomes, is not well known. The usual 8 mg/kg dose cannot be infused in patients over 100 kg (220.5 lb), limited by the manufacturer 800 mg maximal dosage recommendation. This may not be enough to maintain therapeutic levels, which raises doubts about the effectiveness of this medication among the overweight population.

Although some publications describe tocilizumab use in COVID-19 patients, to the best of our knowledge, we report the first case series of successful outcomes among obese patients.10,11 With our series we mainly highlight that tocilizumab seems to be effective to treat hyperinflammation among COVID-19 overweight patients, even when the infusion of the suggested dose (adjusted by their weight) is not feasible to be administered.

Thus, we report a case series of 3 obese COVID-19 patients, with progressing hypoxemia and worsening of symptoms, in which tocilizumab was infused with good results, aiming to aid clinician’s decision making in this population of patients. This report is in accordance with ethics regulations issued by Helsinki Declaration.

Case Presentations

Case 1

A 63-year-old female, with poorly treated hypertension and morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 58 kg/m2) was admitted in the emergency room (ER) with a history of 8 days of fatigue, cough without sputum, and hyporexia, which worsened 24 hours earlier. She had used azithromycin for 5 days and acetylcysteine. On examination, she was tachypneic, with 32 breaths per minute, but no complaints of dyspnea and had a saturation of 85% on room air. An oropharynx swab specimen was taken and the patient was admitted to an isolation ward with an intensive care unit (ICU) transfer solicitation. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan was taken (Figure 1) together with laboratorial examinations (Table 1). She was then started on oxygen 4 L/min, ceftriaxone 2 g to prevent bacterial superinfection, and anticoagulation with enoxaparin 1 mg/kg due to the high risk of thrombotic complications. After 24 hours, the patient was still waiting for ICU admission and had a worsening of hypoxemia, now, complaining of shortness of breath, being started on awake prone position strategy. The decision to administer tocilizumab was discussed with the patient and performed after a negative procalcitonin test. After admission in the ICU, the patient remained stable, with lower oxygen necessity. She complained, however, of a “new” cough with sputum on the fifth day of hospital stay. A control chest CT was made and piperacilin-tazobactam was started after blood sample for cultures and laboratory examinations. She was discharged to the ward 24 hours later, without signs of sepsis, and was sent home 2 days later. Her diagnosis was confirmed by detection of IgM (immunoglobulin M) and IgG antibodies in serum after a negative original RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) sample.

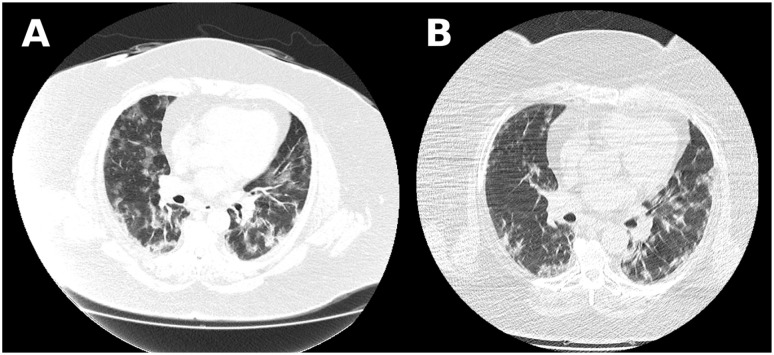

Figure 1.

Case 1 chest computed tomography scan showing bilateral ground-glass opacities with 50% to 75% parenchyma involvement. (A) Image before tocilizumab administration. (B) Image 48 hours after medication, with good reduction of infiltrates.

Table 1.

Laboratory Trends and Tocilizumab Administration of Case 1 Patient.

| Day of hospitalization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratorial tests | 1 | 2 a | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 |

| WBC count (5-10 × 109/L) | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| Neutrophil count (1.5-7 × 109/L) | 3.25 | 3.3 | 3.16 | 2.31 | 1.86 | 1.71 | 1.65 |

| Lymphocyte count (1-5 × 109/L) | 1.71 | 1.85 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.35 | 2.20 | 2.25 |

| Eosinophil count (0.05-0.6 × 109/L) | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.27 |

| Platelet count (150-450 × 109/L) | 170 | 202 | 237 | 240 | 254 | 265 | 266 |

| C-reactive protein (<1.0 mg/dL) | 5.40 | 7.2 | 3.20 | 3.0 | 4.03 | 0.70 | 0.34 |

| Procalcitonin (<0.5 ng/mL) | — | 0.06 | — | 0.05 | — | — | 0.05 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (120-246 U/L) | 1631 | 1604 | 1412 | 1100 | 808 | 603 | 442 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (14-36 U/L) | 81 | 83 | 98 | 90 | 78 | 116 | 52 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (14-36 U/L) | 85 | 85 | 90 | 88 | 76 | 106 | 54 |

| D-dimer (<654 µg/L) | 650 | 603 | 702 | 950 | 630 | 502 | 658 |

| Ferritin (11.0-306.8 ng/mL) | 1500 | 1490 | 2400 | 2308 | 2002 | 1200 | 750 |

| Fibrinogen (180-350 mg/dL) | 587 | 630 | 772 | 750 | 840 | — | 320 |

| Triglycerides (<175 mg/dL) | 204 | 288 | 231 | 258 | 187 | — | 154 |

Abbreviation: WBC, white blood cells.

Day of tocilizumab administration.

Case 2

A 31-year-old, male, obese (BMI of 40.8 kg/m2) male, presented with a 6-day history of dry cough, headache, and fever, which worsened 3 days earlier with progressing dyspnea on exertion. On examination, he was febrile with 38.7 °C (101.6 °F), tachypneic, with a respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute, and had an oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. A chest CT (Figure 2) and laboratorial examinations (Table 2) were made. He was admitted to an isolation ward, an oropharynx swab specimen taken, which later tested positive, and he was started on supplementary oxygen 3 L/min, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID (twice a day) and ceftriaxone 2 g/day. On the fifth day, he had a worsening of hypoxemia, being mobilized in awake prone positioning. Methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg was administrated and he was transferred to the ICU with a pulse oximeter showing 88% saturation on a non-rebreather mask 10 L/min. On admission, the medical staffs decided to infuse tocilizumab after discussion with the patient and a negative procalcitonin test. The next day, the patient reported a relief in the shortness of breath sensation and tolerated O2 support reduction, being transferred to the ward on a 3 L/min catheter, 24 hours later. He progressed well, with a slow but steady supplemental oxygen weaning, being discharged home.

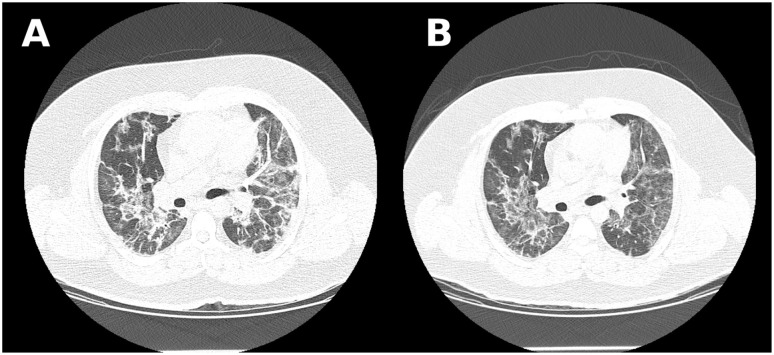

Figure 2.

Case 2 chest computed tomography scan showing bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidations with 50% to 75% of parenchyma involvement. (A) Image before tocilizumab administration. (B) Image 48 hours after medication.

Table 2.

Laboratory Trends and Tocilizumab Administration of Case 2 Patient.

| Day of hospitalization | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratorial tests | 1 | 4 | 5 a | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 12 |

| WBC count (5-10 × 109/L) | 8.5 | 11.0 | 13.2 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 13.2 | 19.3 | 17.6 |

| Neutrophil count (1.5-7 × 109/L) | 6.37 | 8.69 | 8.97 | 6.30 | 4.69 | 10.03 | 12.56 | 10.20 |

| Lymphocyte count (1-5 × 109/L) | 1.02 | 1.21 | 2.90 | 1.84 | 2.34 | 1.98 | 4.10 | 5.45 |

| Eosinophil count (0.05-0.6 × 109/L) | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.17 |

| Platelet count (150-450 × 109/L) | 180 | 343 | 346 | 386 | 342 | 329 | 297 | 330 |

| C-reactive protein (<1.0 mg/dL) | 16.2 | 16.0 | 7.2 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Procalcitonin (<0.5 ng/mL) | — | — | 0.05 | — | 0.06 | — | 0.05 | — |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (120-246 U/L) | 343 | 384 | 380 | 313 | 354 | 323 | — | — |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (17-59 U/L) | 61 | — | 65 | 60 | 89 | 56 | 34 | — |

| Alanine aminotransferase (17-59 U/L) | 98 | — | 133 | 130 | 165 | 160 | 34 | — |

| D-dimer (<630 µg/L) | 451 | 856 | 802 | 1260 | 1680 | 1064 | 1650 | — |

| Ferritin (23.9-336.2 ng/mL) | — | >1500 | >1500 | >1500 | >1500 | 1430 | — | 1300 |

| Fibrinogen (180-350 mg/dL) | — | — | 1357 | 1012 | — | 754 | — | — |

| Triglycerides (<175 mg/dL) | — | 348 | 302 | — | 410 | 307 | — | — |

Abbreviation: WBC, white blood cells.

Day of tocilizumab administration.

Case 3

A 51-year-old, male patient, with hypertension, coronary disease with previous percutaneous revascularization, diabetes, and a BMI of 35 kg/m2 went to the ER with a history of 12 days of daily fever and anosmia. He had worsening of symptoms 24 hours before seeking medical assistance, when he developed intense fatigue and worsening of fever. He had used azithromycin, ivermectin, and corticosteroids since day 1 of fever. On examination, he had a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute and a heart rate of 110 beats per minute. His oxygen saturation was 88% on room air. He was admitted to an isolation ward, a swab specimen was collected, which came back positive, and blood was drawn for laboratory testing (Table 3). He was started on 3 L/min oxygen and unfractioned heparin 5000 mg TID (3 times a day). After about 24 hours, he had worsening of symptoms, now complaining of dyspnea and needing 15 L/min in a non-rebreather mask to maintain O2 saturation of 93%. A chest CT was performed (Figure 3). He was transferred to the ICU, started on awake prone position, and a decision to infuse tocilizumab was made after a negative procalcitonin test. He progressed to a lower need for O2, being discharged to the ward 48 hours later breathing on room air and was sent home 3 days later.

Table 3.

Laboratory Trends and Tocilizumab Administration of Case 3 Patient.

| Day of hospitalization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratorial tests | 1 | 2 a | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| WBC count (5-10 × 109/L) | 10.9 | 12.3 | 12.8 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 8.7 | 9.6 |

| Neutrophil count (1.5-7 × 109/L) | 8.39 | 9.96 | 9.85 | 5.10 | 4.48 | 5.65 | 6.62 |

| Lymphocyte count (1-5 × 109/L) | 1.41 | 1.59 | 1.92 | 1.70 | 1.83 | 2.34 | 2.01 |

| Eosinophil count (0.05-0.6 × 109/L) | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Platelet count (150-450 × 109/L) | 370 | 302 | 393 | 483 | 487 | 481 | 500 |

| C-reactive protein (<1.0 mg/dL) | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 2.0 |

| Procalcitonin (<0.5 ng/mL) | — | 0.05 | — | 0.05 | — | 0.05 | — |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (120-246 U/L) | 624 | 391 | 391 | — | 269 | — | 336 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (17-59 U/L) | 58 | 50 | 38 | 42 | 33 | — | 35 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (17-59 U/L) | 77 | 79 | 63 | 37 | 61 | — | 38 |

| D-dimer (<630 µg/L) | 3880 | — | 1255 | — | 1280 | 5060 | 608 |

| Ferritin (23.9-336.2 ng/mL) | 1458 | — | 1089 | 1109 | 735 | 712 | 801 |

| Fibrinogen (180-350 mg/dL) | 876 | — | 965 | — | 875 | 869 | — |

| Triglycerides (<175 mg/dL) | 152 | — | 140 | — | 90 | 120 | — |

Abbreviation: WBC, white blood cells.

Day of tocilizumab administration.

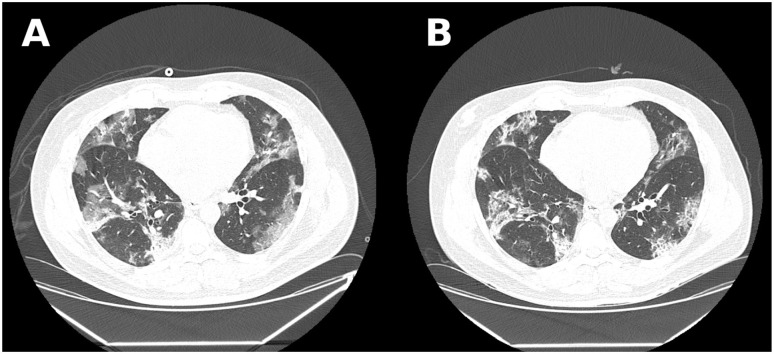

Figure 3.

Case 3 chest computed tomography scan showing bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidations with 25% to 50% of parenchyma involvement. (A) Image before tocilizumab administration. (B) Image 48 hours after medication.

Discussion

In the report, we described the clinical evolution of 3 obese individuals, in different age groups, treated with tocilizumab. In these series, patients were given the antibody in the first few days of worsening hypoxemia, in spite of total disease progression time, and the infusion used the maximum suggested dose (800 mg). This regimen in such population may be considered as an underdosing, although in all cases, the outcome was favorable and patients were discharged from the ICU and, after a short period, the hospital.

Such results backup the findings of Xu and colleagues, 10 in which 21 patients were treated using tocilizumab and experienced an improvement in oxygen saturation, symptoms of dyspnea, and CT scan opacities after a brief period. On the other hand, our findings oppose those of Radbel and colleagues, 11 in which the authors report 2 cases of bad clinical outcomes after the infusion of the interleukin-6 antagonist. In our case series, all patients had a negative procalcitonin test. We believe that this, aligned with the early timing of drug prescription, was imperative in obtaining the favorable outcomes described. The negligence of this aspect of care could be implicated in the spread of an eventual infection and posterior development of septic shock, favored by the immunosuppressive nature of the treatment.

In a recent article by Cavalli and colleagues, 12 the authors reported a good benefit with the infusion of an interleukin-1 antagonist, anakinra, based in a similar rationale as tocilizumab. In their study, the authors used a low threshold for the monoclonal antibody infusion, based only in C-reactive protein and ferritin levels. Huet and colleagues 13 demonstrated good results with high-dose anakinra, using only clinical examination criteria to decide for the infusion, highlighting the importance of a more “preemptive” strategy in interleukin-blocking therapy, as it is for antibiotics in sepsis.

It is also important to note that the apparent sub-dose used (not adjusted to weight of patients) was sufficient to produce favorable results in the evaluated individuals. Worse outcomes, with a potentially fatal prognosis, related to hypoxemia and necessity for intubation in an anticipated difficulty airway, in our series, was prevented by interleukin-6-blocking therapy, lowering length of ICU and hospital stay. We have not found studies that explore the effectiveness of tocilizumab using doses that are supposedly not adequate for the patient’s weight, as in obese. Thus, we emphasize that further robust research is needed in order to evaluate the dose response of this medication in the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

In the pandemic’s scenario, with an overwhelming demand for ICU and hospital care, panic may exert a high demand in physicians aiming to better treat their patients. The loss of clinical equipoise 8 may cause more harm than good. The judicious use of new and experimental therapies for SARS-CoV-2 has to be based in a potential clinical benefit that outweighs the risks and only after a thorough discussion with patient and family.

Conclusion

Our series shows that tocilizumab seems to be a safe therapy, with potential benefits for the treatment of critical COVID-19 obese patients, who present hyperinflammation and progressing hypoxemia. Our outcomes may have been influenced by the timing of treatment, started without waiting for laboratory signs of hyperinflammation, as well as the attempt to assure absence of uncontrolled superinfection. Which factor contributed the most remains unclear, and it is a limitation of the design of our study. Thus, the optimal dose regimen, its best timing of administration, and the real clinical benefits remain to be proven in clinical trials already underway.14-17

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors collected the data, and wrote and contributed to manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of their anonymized information and all the accompanying images in this case report.

ORCID iD: Diego Bastos Porto  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6865-1385

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6865-1385

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Published March 11, 20020. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-COVID-19—11-march-2020

- 2. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Accessed July 3, 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- 3. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052-2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033-1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giannis D, Ziogas IA, Gianni P. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104362. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zhang F, et al. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): the perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108393. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Le RQ, Li L, Yuan W, et al. FDA approval summary: tocilizumab for treatment of chimeric antigen receptor T cell-induced severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome. Oncologist. 2018;23:943-947. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ramnath VR, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Do no harm: reaffirming the value of evidence and equipoise while minimizing cognitive bias in the COVID-19 era. Chest. 2020;158:873-876. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fu B, Xu X, Wei H. Why tocilizumab could be an effective treatment for severe COVID-19? J Transl Med. 2020;18:164. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02339-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu X, Han M, Li T, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:10970-10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Radbel J, Narayanan N, Bhatt PJ. Use of tocilizumab for COVID-19-induced cytokine release syndrome: a cautionary case report. Chest. 2020;158:e15-e19. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, et al. Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e325-e331. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30127-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huet T, Beaussier H, Voisin O, et al. Anakinra for severe forms of COVID-19: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e393-e400. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30164-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. US National Library of Medicine. Tocilizumab in COVID-19 pneumonia (TOCIVID-19). Published March 20, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04317092

- 15. US National Library of Medicine. A study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia (COVACTA). Published March 25, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04320615

- 16. US National Library of Medicine. Tocilizumab for SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) severe pneumonitis. Published March 19, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04315480

- 17. Chinese Clinical Trial Registry. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial for the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in the treatment of new coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) [in Chinese]. Published February 13, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2021. http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=49409