Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the study is to evaluate the impact of heart failure medication education on 30-day all-cause readmission rates and patient-reported satisfaction scores. Methods: This single-center pilot study was conducted at a 396-bed tertiary-care hospital in the Midwest from September 2017 to December 2018. For research purposes, patients were divided into 2 groups. The control group was looked at retrospectively and included patients who received education by the nurse educator. The intervention group was reviewed proactively and included patients who received education by a pharmacy student. The purpose of the study was to compare readmission rates among patients who received medication education from pharmacy students with those who received the same education by the heart failure nurse educator. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause readmission rate among those with a diagnosis of heart failure. The secondary endpoints included patient satisfaction scores by phone survey. The patient satisfaction phone survey was conducted by a single pharmacist 1 week after patient education was provided. Results: For the primary endpoint, there were 222 patients in the treatment group compared with the control group of 941 patients. The treatment group resulted in 30 (13.5%) of the 222 patients being readmitted within 30 days compared with the control group where 186 (19.6%) of the 941 were readmitted (P = .0395). The risk reduction in odds ratio and relative risk of readmission was 0.63 (confidence interval [CI] = 0.42-0.96) for the treatment group and 0.68 (CI = 0.48-0.98) for the control group. For the secondary endpoint, 56 patients were called 1 week after discharge, and there was no significant difference in overall patient satisfaction between groups. Conclusion: This study demonstrated that heart failure medication education provided by the pharmacist or pharmacy student resulted in improved patient outcomes and ultimately a reduction in 30-day all-cause readmission rates.

Keywords: patient education, cardiovascular, clinical services, cost-effectiveness, outcomes research, schools of pharmacy

Introduction

Patients with heart failure (HF) have a significant impact on the health care system in the United States. Heart failure is the fourth leading cause of death attributed to cardiovascular (CV) disease and affects an estimated 6.5 million adults. Further studies estimate that more than 8 million adults will be affected by HF by 2030, leading to a total cost of $69.7 billion in the health care system. 1 Major risk factors associated with HF include coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. Research through the National Center for Health Statistics indicates that one-third of US adults are affected by at least one of these risk factors.

Approximately 1 million patients are hospitalized each year for HF. 2 In 2011, the leading cause of 30-day readmissions for Medicare patients was HF, and it costs approximately $1.75 billion. 3 To encourage improvement in patient outcomes, the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services established a rule in 2012, which reduced reimbursement to hospitals that have readmission rates within 30 days. 4 Therefore, it is extremely important to provide a multidisciplinary approach to care to ensure patients are on correct pharmacotherapy and stay adherent to their medications.

Many studies have been conducted to determine reduction of readmission rates among HF patients; however, these studies have not adequately been powered to detect a difference.5-7 Furthermore, there is limited research that has specifically evaluated the impact of student-led counseling prior to patient discharge. While one published study determined there was no significant difference in readmission rates through pharmacy student–led and pharmacy resident–led counseling to HF patients, it did find an estimated cost avoidance of $4241. 6

Other small studies have shown a favorable effect at reducing readmission rates through pharmacy-led education.8,9 One study found favorable outcomes in transition of care with pharmacy resident–led counseling, with a reduction of 30-day HF readmission rate from 28.1% to 16.6%. However, this study has several limitations, including a small sample size of only 30 patients. 8

Due the limitations of these studies, more research needs to be done with pharmacist-led counseling to HF patients to determine whether there is improvement in health care outcomes, hospital readmission rates, and health care spending. 6

Methods

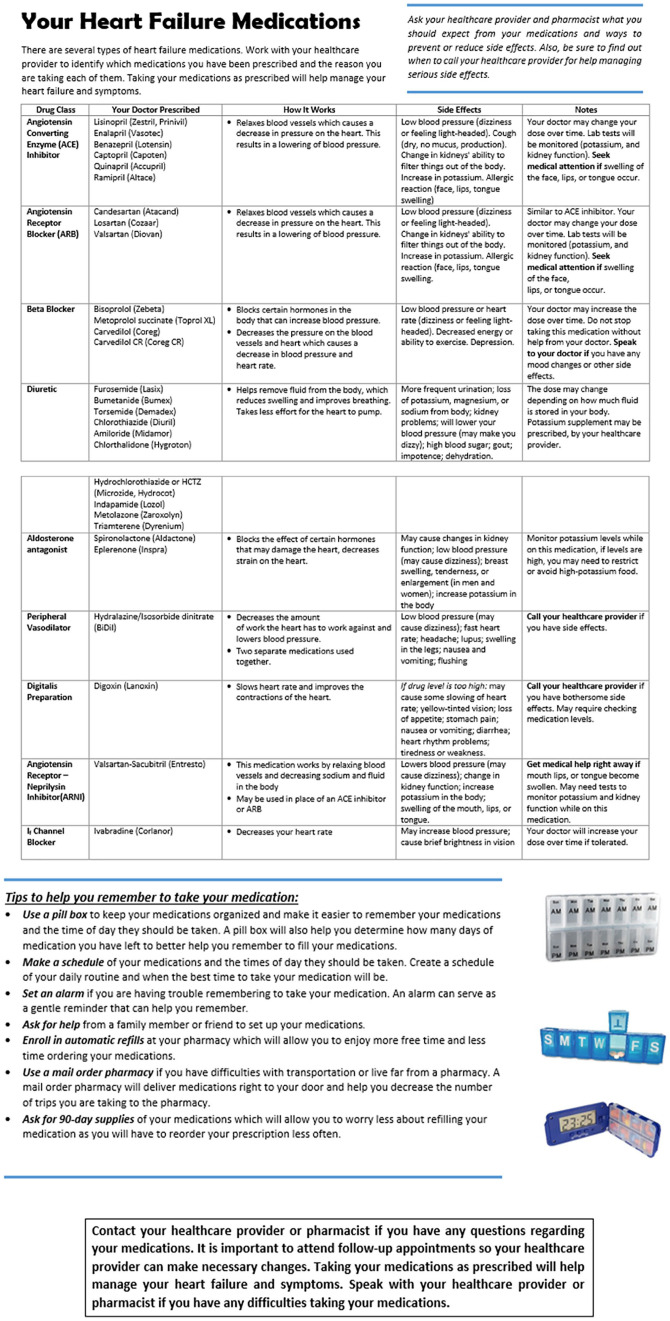

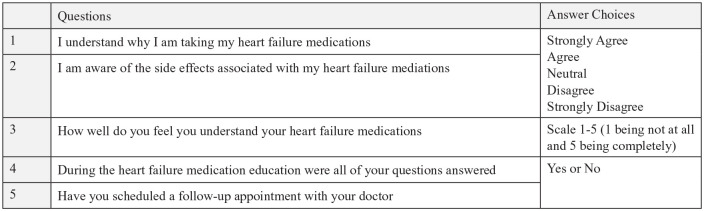

This single-center pilot study was conducted at a 396-bed tertiary-care hospital in the Midwest from September 2017 to December 2018 and was approved by the institutional review board. For research purposes, patients were divided into 2 groups. The control group was looked at retrospectively and included patients who received education by the nurse educator. The intervention group was reviewed proactively and included patients who received education by a pharmacy student. The purpose of the study was to compare readmission rates among patients who received medication education from pharmacy students with those who received the same education by the HF nurse educator. Patients who met inclusion were older than 18 years; diagnosed with HF, counseled by a fourth-year pharmacy student, pharmacist, or HF educator; English speaking; and were able to provide verbal consent to the survey. Patients were identified by the HF educator who is a registered nurse designated to teach patients with an active diagnosis of HF. Patients with complex drug regimens and prior hospitalizations were given priority to receive education by the pharmacy student. Patients who were newly diagnosed with HF were also given priority. In some instances, family members were also educated, especially in circumstances where they were the primary caregiver. The teaching was broken down into 3 parts: disease state, diet, and medication education. Pharmacy students took over the medication portion but the HF educator continued to provide diet and disease state information. Fourth-year pharmacy students were provided in-depth education on HF medications, including their indication and contraindications, mechanism of action, side effects, and adverse reactions. The medication handout used by the pharmacy student can be found in Figure 1, this table was adapted from the heart failure education booklet entitled “ACTively Living with Heart Failure”, a patient education resource provided by the health network. 10 The pharmacist would use the “see one, do one, teach one” approach where they would first model a HF medication education, and then the student would complete one with the pharmacist in the patient’s room. If the pharmacist confirmed the student was ready, they could provide the education independently. Once the education was completed, the pharmacy student then documented this education in a spreadsheet and in the electronic patient chart. The pharmacist or attending physician was instructed to follow-up with patient questions when the student could not answer them. Patients educated by the pharmacy student were provided with verbal education and a written medication information handout that was written at a sixth-grade reading level. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause readmission rate among those with a diagnosis of HF. Readmission rates were captured via a report obtained for quality measures as a tracking necessary for benchmarking HF readmissions. The secondary endpoints included patient satisfaction scores by phone survey. The patient satisfaction phone survey, which can be found in Figure 2, was conducted directly by a single pharmacist 1 week after patient education was provided.

Figure 1.

Medication education handout.

Figure 2.

Phone survey questions used to assess patient satisfaction.

Statistical Analysis

Inferential statistical methods for this study applied χ2 with Yates correction for categorical data and Student’s t test for continuous data. Statistics in R program was used for analysis.

Results

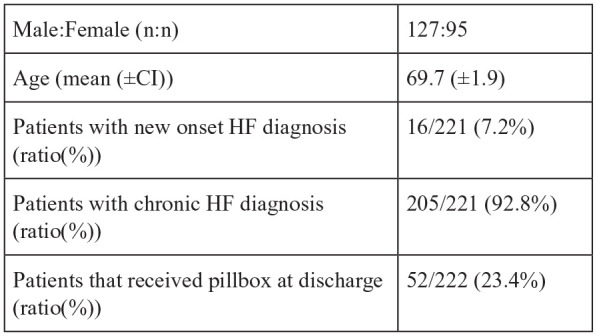

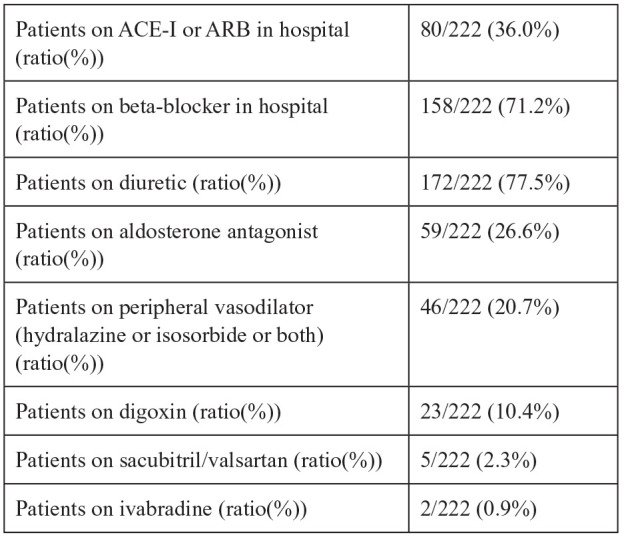

On average, the patients in the treatment group were 70 years old with a chronic HF diagnosis. Figure 3 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the treatment group. Patients were educated on a variety of medications as summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Baseline characteristics for treatment group (n = 222).

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Medications educated on at discharge (n = 222).

Note. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker.

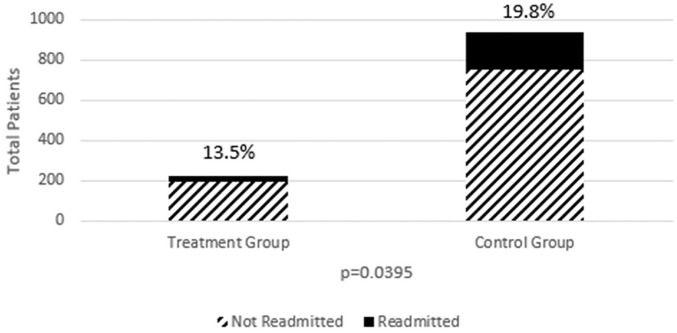

For the primary endpoint, there were 222 patients in the treatment group compared with the control group of 941 patients. Furthermore, in the treatment group, 214 (96.4%) of the 222 patients were educated by pharmacy students and 8 (3.6%) of the 222 patients were educated by the pharmacist during the training of the pharmacy student. The treatment group resulted in 30 (13.5%) of the 222 patients being readmitted within 30 days compared with the control group where 186 (19.6%) of the 941 were readmitted (P = .0395) as depicted in Figure 5. The risk reduction in odds ratio and relative risk of readmission was 0.63 (confidence interval [CI] = 0.42-0.96) for the treatment group and 0.68 (CI = 0.48-0.98) for the control group.

Figure 5.

All-cause readmission data for treatment versus control group.

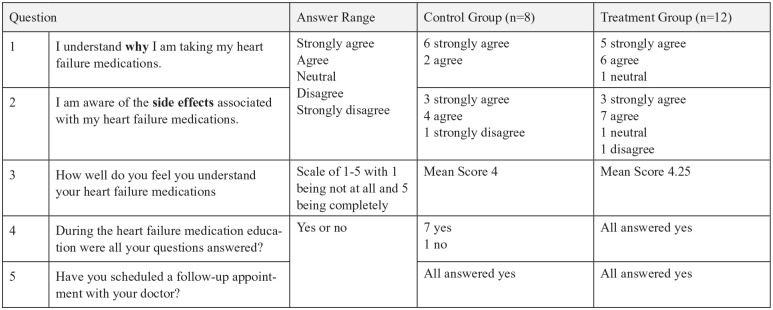

For the secondary endpoint, 56 patients, from both the control and treatment group, were called 1 week after discharge to conduct a phone survey and there was no significant difference in overall patient satisfaction between groups. This secondary analysis was stopped early due to no significant difference and the time constraints/feasibility of the pharmacy resident calling patients directly. Although 56 patients were called, only 20 answered after 2 attempts of calling. The phone survey results are summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Phone survey results.

Discussion

The mean cost for a HF readmission is $9051 (range = $8990-$9113). 11 The financial incentive to reduce readmission rates to avoid penalties is imposed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The transition of care is vital to the proper medical management in patients with HF, both while the patient is admitted and on discharge from the hospital. Patients with HF often have complex treatment regimens and multiple comorbid conditions, making adherence difficult. Clinical pharmacists remain an integral part of the health care team, as their clinical knowledge and expertise has been shown to improve medication adherence through patient education. The Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network recommend using a pharmacist to resolve common drug-related problems and improve outcomes in HF patients. 12

Pharmacy involvement through HF medication education had a positive impact on readmission rates. A reduction in readmission rates also decreases cost, which may help justify the cost for a dedicated pharmacist. This study was one of the first of its kind to look at pharmacy student-ran HF medication education. The sample size of this study was another strength along with the length of 15 months.

Overall, there are some key limitations of this study. First, this project was dependent on pharmacists having fourth-year pharmacy students on rotation each month. Some studies have shown seasonal trends of HF hospitalizations, which demonstrate increased admissions and mortality during the winter months. The 396-bed tertiary-care hospital had pharmacy students consistently during this high-risk period. When pharmacy students were not available, the HF nurse educator provided all the education, including the medication portion. Another limitation was that it was difficult to classify HF. As data was extracted from medical records, there was a wide variability in the way physicians classified HF. In the treatment group, approximately 62% were classified with systolic HF, which is defined as ejection fraction of 40% or less, leaving 38% of patients classified with diastolic HF, defined as ejection fraction greater than 40%. It would have been interesting to look more in depth at trends regarding the classification of HF; however, due to limited information in medical records, this was not clear. Complexities of documentation in the medical record also made it challenging to obtain baseline characteristics for the control group, but it is recognized that more detailed information would have been beneficial. Another limitation of the health system included the fact that the staffing model does not currently support a dedicated unit-specific pharmacist to provide recommendations to optimize the treatment regimen; therefore, it is not certain that all HF patients are being treated with evidence-based treatment regimens. It was noted that only 36% of patients were on an ACE-I (angiotensin-converting enzyme) or ARB (angiotensin receptor blocker) at the time of discharge. The reason was unclear given Guideline-directed medical therapy. This was identified as a potential opportunity for increased pharmacist involvement and area for future focus. During the time of the study, on average, 25% of the patients followed up with a heart specialist at the tertiary care hospital clinic. This number is expected to continue to increase as services expand.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that HF medication education provided by the pharmacy team resulted in improved patient outcomes and ultimately a reduction in 30-day all-cause readmission rates. There was no reported significant difference in overall patient-reported satisfaction regarding the phone survey 1 week post discharge. The results also identified an opportunity to expand the service and strengthen support for pharmacy involvement in providing excellent patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ron Jones, PharmD, for his help with the statistical analysis. They also thank all the pharmacy students who helped educate patients as part of their advanced pharmacy practice experience.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Aubrey A. Mills  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2744-3664

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2744-3664

References

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018; e67-e492. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. Accessed November 2, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Peacock WF, Fonarow GC, Ander DS, et al. Society of Chest Pain Centers recommendations for the evaluation and management of the observation stay acute heart failure patient: a report from the Society of Chest Pain Center acute heart failure. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2008;7(2):83-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hines AL, Barrett ML, Jiang HJ, Steiner CA. Conditions with the largest number of adult hospital readmissions by payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #172. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed August 27, 2018.

- 5. Murphy JA, Schroeder MN, Rarus RE, Yakubu I, McKee SOP, Martin SJ. Implementation of cardiac transitions of care pilot program: a prospective study of inpatient and outpatient clinical pharmacy services for patients with heart failure exacerbation or acute myocardial infarction. J Pharm Pract. 2019;32:68-76. doi: 10.1177/0897190017743129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Szkiladz A, Carey K, Ackerbauer K, et al. Impact of pharmacy student and resident-led discharge counseling on heart failure patients. Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2013;26(6):574-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell SP, Schnipper JL, Goggins K, et al. Effect of pharmacist counseling intervention on health care utilization following hospital discharge: a randomized control trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):470-477. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3596-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salas CM, Miyares MA. Implementing a pharmacy resident run transition of care service for heart failure patients: effect on readmission rates. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(1):S543-S547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jackevicius CA, Leon NK, Lu L, Chang DS, Warner AL, Mody FV. Impact of a multidisciplinary heart failure post-hospitalization program on heart failure readmission rates. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(11):1189-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taking Medication. In: ACTively Living with Heart Failure. Customized for Lutheran Health Network. Krames, StayWell, LLC: 2013, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mayr FB, Talisa VB, Balakumar V, et al. Proportion and cost of unplanned 30-day readmissions after sepsis compared with other medical conditions. JAMA. 2017;317(5):530-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson SL, Marrs LC. A review of the role of the pharmacist in heart failure transition of care. Adv Ther. 2018;35:311-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]