Abstract

Background

There is heterogeneity in conceptualizations of resiliency, and there is, to date, no established theoretically driven resiliency assessment measure that aligns with a targeted resiliency intervention. We operationalize resiliency as one’s ability to maintain adaptive functioning in response to the ongoing, chronic stress of daily living, and we use a novel resiliency measure that assesses the target components of an evidence based resiliency intervention. We present our resiliency theory, treatment model, and corresponding assessment measure (Current Experience Scale; CES).

Methods

To establish the psychometric properties of the CES, we report the factor structure and internal consistency reliability (N = 273). Among participants in our resiliency intervention (N = 151), we explored construct validity in terms of associations with theoretical model constructs, a validated resiliency measure, and sensitivity to change from before to after the intervention.

Results

Results indicated that a 23-item, 6-factor solution was a good fit to the data (RMSEA = .08, CFI = .97; TLI =.96) and internal consistency was good (α = .81 to .95). The CES showed correlations in the expected direction with resiliency model constructs (all p’s < .001) and significant post intervention improvements.

Conclusion

Our resiliency theory, treatment model, and outcome appear aligned; the CES demonstrated promise as a psychometrically sound outcome measure for our resiliency intervention and may be used in future longitudinal studies and resiliency building interventions to assess individuals’ resiliency to adapt to ongoing stress.

Keywords: resiliency, stress, health, measurement, theory

Background

In the U.S., there is mounting chronic stress and a growing number of daily stressors, 1 emphasizing an increasingly important need for evidence based resiliency interventions and corresponding assessments. A 2019 review depicted a lack of consensus for the conceptualization and measurement of resilience. 2 Although there is no agreed upon definition, resiliency is often characterized as one’s ability to “bounce back” following exposure to risk or to adversity.3–12 Additionally, recent reviews of resilience research revealed three core components of resilience, which include the presence of adversity, protective factors that overcome this adversity, and a subsequently more positive outcome, or growth.13,14 There is a great demand for mind-body resiliency interventions that represent conceptually driven characterizations of resiliency, with clearly defined and measurable end points and process variables.

Resilience has been conceptualized as a personality trait or cluster of traits that refer to one’s ability to adapt to adversity and restore equilibrium.15–25 Resiliency has also been conceptualized as a process or capacity that can be enhanced or taught.26–29 Specifically, individuals can develop resilient skills and perspectives, including manifesting adaptive behaviors, engaging in problem solving skills, maintaining optimistic perspectives, sustaining positive social functioning, utilizing positive emotion eliciting coping strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, benefit finding, humor), and finding meaning.26,30

Resiliency is often characterized as the capacity to maintain healthy functioning after an acute stressor or traumatic event.31–33 Some conceptualize resiliency as managing adversity of daily living, as well as coping with the downstream effects from major life events (e.g., sadness from loss of a loved one, financial stress due to job loss). Importantly, current experiences of chronic stressors are associated with greater vulnerability to deleterious health and well being.34–36 Reflecting this present focus, we developed a resiliency framework that illustrates an adaptive response to chronic stress, caused by everyday stressors and major life events. Resiliency thus is, specifically, the ability to maintain adaptive functioning in response to the ongoing stress of daily living. 37

Our framework is informed by the diathesis stress model, which is a process approach that posits resiliency is the outcome of an individual’s experiences and environment in combination with one’s inherent attributes. 38 Moreover, our framework builds on conceptualizations of resiliency as a malleable construct26,27 that reflects multiple biopsychosocial factors 39 including qualities that buffer against the stress response and promote adaptive growth (e.g., spiritual connectedness, positive expectancies). It emphasizes Tedeschi’s construct of growth, which is positive development following adversity. 40

Extant measures assess resiliency as a dispositional trait, a reflection of external factors (e.g., family cohesion), or an amalgam of intrapersonal characteristics (e.g., religiosity) that are not all aligned with our resiliency theoretical model.17,26,41,42 In behavioral intervention research, it is important to have outcome assessments that specifically tap into the targeted intervention components and change processes. 43 The pairing of a theoretically driven intervention and corresponding assessment measure is critical to accurately assess intervention effects. Thus, we needed an outcome measure that captured our conceptualization of resiliency and could be relevant for other interventions and studies that conceptualize resiliency as modifiable and multidimensional. We present our resiliency theory, treatment, and corresponding assessment measure (Current Experience Scale; CES).

Resiliency Treatment Theory and Model

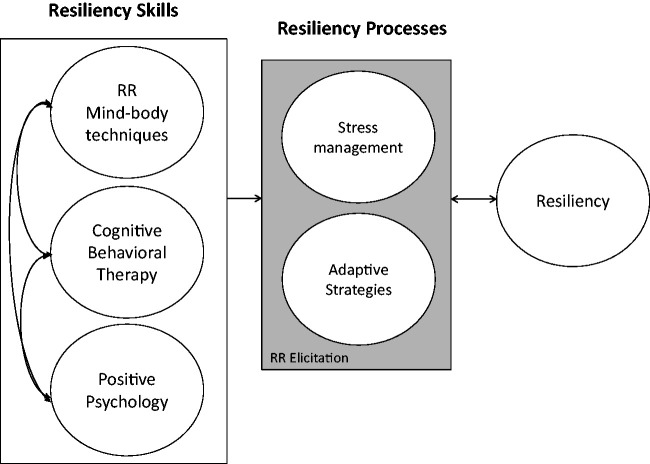

Our resiliency treatment model (see Figure 1) frames adjustment to ongoing, chronic stress as a dynamic process which can be demonstrated by practicing a set of core coping skills (i.e., Relaxation Response (RR) elicitation, stress awareness and management, and adaptive strategies). Based on this model, we developed the Stress Management and Resiliency Training/Relaxation Response Resiliency Program; SMART-3RP). The theoretical model emphasizes the development and effective practice of these core skills in response to chronic stressors. The Relaxation Response (RR) refers to a physical state of deep relaxation that is modulated by the parasympathetic nervous system where one experiences a sense of calm and well being that can be elicited through relaxation techniques. 44 Conceptually, Stress Management processes draw on cognitive behavior therapy and include improved coping skills and reductions in psychological symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression), whereas Adaptive Strategies processes draw on positive psychology and include increased positive psychological states and social connectedness (e.g., positive affect, empathy). Stress Management and Adaptive Strategies processes 1) interact with each other to promote resiliency and 2) are bidirectionally related to resiliency.

Figure 1: Resiliency treatment model.

Resiliency Treatment Program

This conceptual model guides the SMART-3RP treatment program. There are three essential components to our program (see Table 1). First, participants practice RR techniques. Each session presents different strategies to elicit the RR, all of which involve creating and keeping a mental focus, by repeating a concept, maintaining an open, receptive attitude, and letting go of extraneous thoughts. Second, the program teaches Stress Awareness. We explore how stress affects thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, behaviors and relationships and examine individual responses to a stressor. Third, participants learn about Adaptive Strategies. With a new foundation of Stress Awareness, we examine and practice four types of Adaptive Strategies to buffer stress. a) Reappraisal and Coping. Our reappraisal approach is based on a blending of cognitive therapy, which recognizes the link between thoughts and emotions, and positive psychology, which promotes adaptive thoughts and emotions. Participants learn how to reframe a stressor with positive/adaptive emotions as well as review and modify the corresponding thoughts, physical sensations and behaviors. During sessions, we also regularly access adaptive coping skills, such as creativity and humor, to demonstrate how to buffer oneself against stressors. b) Positive Perspectives. Sessions emphasize the expression of positive emotions and character strengths. Challenges are observed through a lens of positive meaning and expectation. Daily appreciations are noticed and experienced, which causes a shift in one’s perspectives to focus on small, positive experiences such as smells, tastes, interactions, and surprises. c) Social Connectedness. Sessions focus on strengthening participants’ ability to assess and access social support, which includes giving and receiving. The treatment manual delves into corresponding prosocial behaviors and empathy to enhance feelings of connectedness to oneself and others. d) Healthy Behaviors. Participants are encouraged to set individual goals of physical activity, healthy and mindful eating, and recuperative sleep.

Table 1.

Stress Management and Resiliency Training: Relaxation Response Resiliency Program.

|

Intake Session Introducing Resiliency and the Relaxation Response |

• Resiliency and the Relaxation Response • Core components of the program • Setting SMART and resiliency goals • Monitoring Stress and Coping |

|

Session 1 Stress Management and Resiliency Training |

• Stress Response & Relaxation Response and Allostatic Load • Energy Battery: stress-inducing and resiliency inducing factors • Appreciation • RR-elicitation method: single pointed focus meditation and breath awareness |

|

Session 2 The Relaxation Response |

• Stress Warning Signs • Recuperative Sleep• Mini RR • RR-elicitation method: body scan or autogenic training |

|

Session 3 Stress Awareness |

• Identifying emotions and positive physical sensations• Social Support• RR-elicitation method: Mindful Awareness |

|

Session 4 Mending the Mind and Body |

• Thought Distortions • Negative Automatic Thoughts • RR-elicitation method: chair yoga |

| Session 5Creating An Adaptive Perspective |

• Creating adaptive perspectives • Problem-Solving vs. Acceptance • Healthy Eating • RR-elicitation method: insight imagery |

| Session 6Promoting Positivity |

• Strategies for enhancing positivity • Relaxation Signals • Promoting physical activity • RR-elicitation method: contemplation and lovingkindness meditation |

|

Session 7 Healing States of Mind |

• Empathy and self compassion • Creativity • RR-elicitation method: compassion meditation |

|

Session 8 Humor & Staying Resilient |

• Staying Resilien t• Humor • RR-elicitation method: idealized self |

Current Experiences Scale Measure

The Current Experiences Scale, 45 captures our holistic, present focused resiliency framework conceptualization. The CES is a modified version of the Post Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), 46 a well validated measure of growth after a traumatic event, which queries for comparative recall of previous levels of functioning. The PTGI captures the key aspects of our resiliency model and treatment program: appreciation for life, personal strengths, new possibilities, spiritual change, and relating to others. The CES scale authors added a sixth health behaviors subscale, which fits well with the behavioral components of our resiliency model and program. Furthermore, the CES measures current functioning, thus enabling computation of changes that may occur during and after exposure to resiliency interventions.

To establish the CES as a resiliency outcome measure, we investigated the CES’s psychometric properties. Specifically, we sought to: (1) confirm the intended 6-factor structure of the CES (2) establish the internal consistency reliability of the full CES measure and subscales (3) explore sensitivity to change from before to after the SMART-3RP, and (4) explore construct validity in terms of associations with our resiliency model’s Stress Management and Adaptive Strategies constructs, as well as with a validated resiliency measure (Resilience Scale-14 [RS-14]). We hypothesized that the 6-factor structure would be a good fit to the data; the CES would show acceptable internal consistency; CES scores would significantly increase from before to after the SMART-3RP; and the CES would be significantly negatively correlated with measures of stress processes and significantly positively correlated with measures of resiliency processes.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 273 adults (Mage=45.13, SD = 13.37) who completed the CES as part of a baseline assessment for clinical care as part of four research studies.47–50 These studies were randomized trials with wait-list control or wellness educational comparison groups, in-person and group based, and led by trained facilitators from a myriad of clinical backgrounds (e.g., nurse practitioners, psychologists, clinical social workers). The combined sample was predominantly female (69%), white (64%; 12% Hispanic), college educated (76%), partnered (58%), and employed (84%). To assess sensitivity for change, we analyzed a convenience sample of 151 participants who completed resiliency treatment groups from 2017–2020. Participants provided written informed consent; approval was obtained by the Partners Human Research Committee and the University of Miami Human Subjects Research Office prior to conducting study procedures.

Measures

Resiliency

Current experience scale

The CES is a 25-item measure that reflects current functioning in the domains of appreciation for life (AL), adaptive perspectives (AP), personal strength (PS), spiritual connectedness (SC), relating to others (RO), and health behaviors (HB). 45 The CES total score can range from 0–125, with higher scores indicating greater resiliency.

Construct validity

The Resilience Scale-14 (RS-14) is a well validated assessment; 17 (range 14 – 98) which is based on a perspective that resiliency is a trait that promotes adaptive functioning. Specifically, the RS measures resiliency as a function of self reflection, whereas the CES assesses resiliency through questions related to coping, perspectives, and actions to manage stress. Thus, the RS-14 assessment of resiliency has overlapping aspects, but is also distinct from our resiliency conceptualization.

Construct validity measures from our resiliency framework

Stress management, depression, generalized anxiety, and worry measurement

We measured several aspects of stress and coping using validated self-report measures. The Measure of Current Status-Part A (MOCS-A) was used to measure an individual’s perceived ability to employ coping skills and stress management techniques; this is a 13-item instrument with scores ranging from 0–52, where higher scores represent greater coping ability with respect to stress reactivity. 51 We used the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 item (PHQ-8) to measure symptoms of depression and functional impairment during the previous two weeks. 52 Scores range from 0–24, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms of depression. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item (GAD-7) questionnaire was used to assess symptoms of anxiety during the previous two weeks. Scores range from 0–21, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms of anxiety. 53 The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) is a 3-item measure used to assess the trait or tendency towards worry. Scores range from 3–15, with higher scores indicating greater levels of worry. 54

Adaptive strategies

Positive psychology skills specifically target adaptive strategies through the promotion of positive psychosocial processes, which were assessed with validated self-report measures. We used the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) to measure optimism; it is a 10-item self-report measure which assesses individual differences in generalized optimism versus pessimism, where higher scores indicate greater optimism. 55 We used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; positive scale) to measure positive affect; it is a 10-item scale with scores ranging from 1–5, where higher scores indicate greater positive affect. 56 The Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Scale (MOS-SSS) is an 8-item survey which assesses five dimensions of social support including emotional, informational, tangible, and affectionate support as well as positive social interaction. Scores on the MOS-SSS range from 1–5, with higher scores indicating greater perceived support. 57 Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) is a self-report measure which assesses cognitive and affective dimensions of empathy. We used the 7-item Perspective Taking subscale with higher scores indicating greater levels of empathy. 58 The Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R) is a 12-item scale that measures trait mindfulness, conceptualized as the ability to be mindful in everyday life (i.e., through an open, present moment orientation), with higher scores representing greater mindfulness. 59

Data Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis 60 with categorical indicators, oblique rotation, and robust weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) was conducted using MPlus version 6.0 to assess whether the CES 25-item, 6-factor model was appropriate. Model fit was examined using a set of model fit indices according to established cut offs: comparative fit index (CFI) > .95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) >.95, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <.08. 61 Individual item factor loadings were also examined to ensure substantive loadings (>.60). Modifications were made to improve model fit, item factor loadings, and modification indices that suggested changes consistent with our conceptual model. The missing data rate for these analyses was 5% (n= 14, with 11 participants missing data on one CES item, and 3 participants missing data on two CES items). Maximum likelihood estimation, MPlus’ default procedure for handling missing data, was used so that all available cases could be included in these analyses.

Once the final factor structure was identified, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency reliability of the total score and identified subscale scores. To assess the measure’s sensitivity to change over time, paired-samples t-tests were used to examine changes in mean CES scores from before to after participation, complete cases, in the SMART-3RP intervention (n = 151). Construct validity was assessed with theoretically related constructs within the SMART-3RP model. Specifically, positive correlations were demonstrated between the CES and measures of self-efficacy, optimism, positive affect, empathy, acceptance, and coping; negative correlations were demonstrated between the CES and measures of emotional distress, worry, anxiety, and depression. Zero-order correlations were also examined between the CES total scores and the RS-14 in a subsample of participants (n = 79).

Results

Factor Structure

The initial 6-factor model showed acceptable model fit for some fit indices, but there was sufficient room for improvement (RMSEA = .09 [90% CI = .08 – 1.0]; CFI = .95; TLI = .94). Modification indices suggested correlating the error terms from the spiritual connectedness and appreciation for life factors. Given that spirituality is thought to involve meaning, purpose, and appreciation for life, 62 correlating these error terms seemed theoretically appropriate. Modification indices revealed substantial item overlap between two items on the relating to others subscale: item 1 (“I can count on people in times of trouble”) and item 2 (“I have a sense of closeness with others”). Based on this redundancy, the item with the higher factor loading (item 2) was retained and the item with the lower factor loading (item 1) was removed. The fourth item on the health behavior subscale (“I am good at managing stress”) was also suggested via modification indices to better represent personal strengths than health behaviors, which seemed to have face validity given that the way the item is written reflects an individuals’ perception of their skills. Lastly, the third item on the health behavior factor (“I get regular physical checkups”) demonstrated a relatively low item factor loading as compared to the factor loadings for all of the other CES items (R2 = .32) and was removed. The 6-factor model was re-specified making each of these modifications.

The final scale was a 23-item solution that was a good fit to the data (RMSEA = .08 [90% CI = .07 – .08]; CFI = .97, TLI = .96), with all items showing strong loadings on hypothesized factors (Table 2). Internal consistency reliability was good for the CES total score and all subscale scores (α = .81 to .95). Each subscale was correlated with one another and with the CES total (all p’s < .001) (data not shown).

Table 2.

Item Factor Loadings and Internal Consistency for the Final 23-Item Measure (N= 273).

| Total score α = .95 | ALα = .81 | NPα = .83 | PSα = .87 | SCα = .84 | ROα = .82 | HBα = .83 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I know my priorities about what is important in life. | .74 | |||||

| 2. I try to change things that need changing. | .64 | |||||

| 3. I appreciate the value of my own life. | .84 | |||||

| 4. I feel self-reliant | .69 | |||||

| 5. I have an understanding of spiritual matters. | .92 | |||||

| 6. I take care of my health. | .90 | |||||

| 7. I have a sense of closeness with others. | .79 | |||||

| 8. I know that I can handle difficulties. | .84 | |||||

| 9. I am willing to express my emotions. | .71 | |||||

| 10. I am able to accept the way things work out. | .82 | |||||

| 11. I appreciate each day. | .91 | |||||

| 12. I engage in good health behaviors. | .87 | |||||

| 13. I have compassion for others. | .74 | |||||

| 14. I’m able to do good things with my life. | .86 | |||||

| 15. I watch for new opportunities. | .86 | |||||

| 16. I put effort into my relationships. | .72 | |||||

| 17. I have a strong religious faith. | .91 | |||||

| 18. I am aware of how strong I am. | .87 | |||||

| 19. I know how wonderful people are. | .77 | |||||

| 20. I am developing new interests. | .72 | |||||

| 21. I accept needing others. | .70 | |||||

| 22. I am good at managing stress. | .81 | |||||

| 23. I am establishing a new path for my life. | .75 |

Note. AL = appreciation for life, AP = new perspectives (‘new perspectives), PS = personal strength, SC = spiritual connectedness, RO = relating to others, HB = health behaviors.

Sensitivity to Change

Total scores on the CES significantly increased from before to after participation in the SMART-3RP (p < .001) (Table 3). Significant increases were also observed for the personal strengths (p < .001), adaptive perspectives (p < .001), health behaviors (p < .001), and appreciation for life subscales (p < .001), spiritual connectedness (p < .001), and relating to others (p = .004). The total CES effect size for statistically significant change was moderate (d = .46).

Table 3.

CES Changes Pre Post Resiliency Training (N = 151).

| M (SD) pre | M (SD) post | t-Score | Cohen’s d | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES- Total | 75.83 (15.29) | 82.78 (14.59) | 6.74 | .46 | <.001 |

| CES- AP | 15.91 (4.16) | 17.89 (3.82) | 6.87 | .49 | <.001 |

| CES- PS | 15.65 (3.89) | 17.44 (3.50) | 6.80 | .48 | <.001 |

| CES- SC | 5.03 (2.75) | 5.52 (2.58) | 3.72 | .18 | <.001 |

| CES- RO | 21.26 (4.58) | 22.15 (4.36) | 2.91 | .20 | .004 |

| CES- HB | 7.03 (1.77) | 7.69 (1.72) | 5.26 | .38 | <.001 |

| CES- AL | 10.96 (2.60) | 12.03 (2.21) | 6.40 | .44 | <.001 |

N = 151 from the BHI sample (received SMART-3RP). AL = appreciation for life, AP = adaptive perspectives, PS = personal strength, SC = spiritual connectedness, RO = relating to others, HB = health behaviors.

Validity

Table 4 shows zero-order correlations between the CES and Stress Management and Adaptive Strategies measures. The CES total score showed correlations in the expected directions with all variables (all p’s < .001). There was also a strong, positive correlation between the CES total score and RS-14 (r = .81; p < .001).

Table 4.

Zero-Order Correlations Between the CES Total Score and Resilience Components (N = 151).

| Pearson r | |

|---|---|

| Adaptive strategies | |

| Mindfulness (CAMS-R) | .61** |

| Optimism (LOT-R) | .50** |

| Positive Affect (PANAS-P) | .66** |

| Empathy (IRI) | .39** |

| Social support (MOS-SSS) | .45** |

| Improved Stress Management | |

| Coping (MOCS-A) | .54** |

| Worry (PSWQ) | −.26* |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | −.27** |

| Depression (PHQ-8) | −.29** |

Note. The correlation of the CES with optimism and social support is based on a subsest of N = 82 participants.

*=p < .01.

**=p < .001.

Discussion

To demonstrate an approach to pairing a resiliency outcome measure with a targeted resiliency intervention, this study presented a theoretical model of resiliency, a targeted resiliency intervention, and corresponding resiliency assessment measure and investigated the psychometric properties of the CES as a measure of resiliency. We posit that resiliency is achieved when an individual develops skills to cope with ongoing stress adaptively (i.e., returning to homeostasis after experiencing a stressor) and experiences growth enhancement (i.e., achieving a higher level of functioning). This growth, in turn, facilitates enhanced coping. Specifically, we view the process of attaining resilience as the acquisition of stress management and growth enhancement strategies, and the ability to utilize these skills and personal resources effectively in response to ongoing, often chronic, stressors.

We demonstrated the utility of a measure that captures this process and aligns with a theoretically driven resiliency intervention. The CES can be administered across multiple time points, thus capturing resiliency as a dynamic growth process. 63 In pilot work, we have seen notable post treatment improvement in the CES.48,64 Thus, by pairing a new resiliency outcome measure with an evidence based targeted resiliency intervention, this study elucidates how a theoretical model of resiliency can be translated into a targeted resiliency intervention based on a conceptual model and how the development of a corresponding resiliency assessment measure contributes to the literature on model driven, evidence based interventions.

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis of the initial 25-item CES revealed good model fit, though minor modifications were made to improve model fit based on statistical modification indices, item factor loadings, and theoretical considerations. After the final factor structure was identified, Cronbach’s alpha showed good internal consistency reliability of the total score and identified subscale scores (α = .81 – .95). We observed a strong correlation between the modified CES and the RS-14 indicating good construct validity. In other words, high levels of resiliency as measured by the CES are associated with high levels of resiliency as measured by the commonly used RS-14, directly supporting the utility of the CES as an assessment of resiliency. At the same time, the correlation between these two measures indicated an appreciable amount of unique variance, suggesting that the CES is still capturing distinct components of the resiliency construct.

We also investigated construct validity with theoretically related constructs of Stress Management and Adaptive Strategies processes within our resiliency theoretical model. The pattern of results indicated that the CES measure was indeed associated with these processes as expected. Findings demonstrated positive correlations between the CES and measures of optimism, positive affect, empathy, acceptance, and coping and negative correlations between the CES and measures of worry, anxiety, and depression. Participants reporting greater resiliency also reported high levels of trait mindfulness, social support, and dispositional optimism. High resiliency was related to higher empathy and the ability to use coping strategies and stress management techniques. As expected, high resiliency correlated with lower levels of worry, anxiety and depressive symptoms.

There are, however, limitations to the present study. First, the CES measure is subject to positive reporting or social desirability bias. Second, although we guided our changes to the CES model by empirical modification indices and theoretical considerations, future research could administer the full 25-item measure to allow for comparison and further study of our final 23-item model. Third, the results for construct validity may be influenced by shared method variance, as these analyses all focused on self-report measures. Fourth, our investigation was an amalgamation of several populations; future work should examine population characteristics and the generalizability to other diverse groups.

One of the most promising aspects of this work is the possibility of using this measure to assess change in resiliency following an intervention as well as to assist intervention participants in identifying skill areas for personal growth. The current results regarding sensitivity to change provide preliminary support for using the measure in this way. Another way that the CES might be used in future research would be as an awareness raising tool, with careful efforts paid to not prescribing growth or benefit finding, which can be detrimental, 65 but rather as a means of fine tuning people’s efforts to enhance their abilities to manage daily stressors. Future research should be done to assess the validity of the CES across diverse populations and characteristics (e.g., groups with diverse gender, socioeconomic status, racial and cultural identities).

Conclusion

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the need for an examination of interventions that may promote health and well-being during a critically stressful time. By promoting resiliency among at risk groups, we can mitigate the effects of the virus on people’s mental health and well-being as we have done in a wide variety of other medical conditions using the relaxation response, resiliency, and other stress management programs. Our targeted approach of using the CES to measure concepts that reflect the relaxation response theoretical model, as well as those skills that are targeted by our resiliency intervention, is a necessary step forward within the psychosocial intervention literature. Placing this study in a larger context of the growing field of positive psychology, it is our intention to add the CES to the compendium of assessment materials that focus on adaptive behaviors and personal strengths in the face of adversity. We hope that this resiliency model and psychometrically valid measure will serve to generate further discussion around specific, teachable skills that can promote resiliency and the testing of possible resiliency mechanisms.

Footnotes

Data Accessibility Statement: The data reported in this paper are human subject data from clinical services. As such, the data are not publicly available.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by funds from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH T32AT000051-16; Dr. Luberto. NCCIH K23AT010157; Dr. Hall) and the National Cancer Institute (K24 CA197382 04; Dr. Park).

ORCID iD: Elyse R Park https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6319-264X

Christina M Luberto https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8866-6362

References

- 1.American Psychological Association. Stress in America: A National Mental Health Crisis.™ https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/sia-mental-health-crisis.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- 2.Vella SL, Pai NB. A theoretical review of psychological resilience: defining resilience and resilience research over the decades. Arch Med Health Sci. 2019; 7:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutter M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev Psychopathol. 2012; 24:335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu G, Feder A, Cohen H, et al. Understanding resilience. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013: 7:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004; 59:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene RR. Resilience. In Mizrahi T. ?0026; Davis L. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Social Work (20th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 526–531). Washington, DC: NASW Press & Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene RR. A study of Holocaust survivors: implications for curriculum. J Soc Work Educ. 2010; 46:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masten AS. Ordinary Magic Resilience in Development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masten AS, Tellegen A. Resilience in developmental psychopathology: contributions of the project competence longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 2012; 24:345–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russo SJ, Murrough JW, Han M-H, Charney DS, Nestler EJ. Neurobiology of resilience. Nat Neurosci. 2012; 15:1475–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith-Osborne A. Life span and resiliency theory: a critical review. Adv Soc Work. 2017; 8:152–168. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stainton A, Chisholm K, Kaiser N, Rosen M, Upthegrove R, Ruhrmann S, Wood S. Resilience as a multimodal dynamic process. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019; 13:725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013; 18(1):12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greeff AP, Ritman IN. Individual characteristics associated with resilience in single-parent families. Psychol Rep. 2005; 96:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacelon CS. The trait and process of resilience. J Adv Nurs. 1997; 25:123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993; 1:165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beardslee WR. The role of self-understanding in resilient individuals. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1989; 59:266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bebbington PE, Sturt E, Tennant C, Hurry J. Misfortune and resilience: a community study of women. Psychol Med. 1984; 14:347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byrne C, Love B, Browne G, Brown B, Roberts J, Streiner D. The social competence of children following burn injury: a study of resilience. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1986; 7:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caplan G. Loss, stress, and mental health. Commun Mental Health J. 1990; 26:27–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masten AS, O’Connor MJ. Vulnerability, stress, and resilience in the early development of a high risk child. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989; 28:274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002; 82:112–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richmond JB, Beardslee WR. Resiliency: research and practical implications for pediatricians. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1988; 9:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985; 147:598–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003; 18:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014; 5:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown DD, Kulig JC. The concepts of resiliency: Theoretical lessons from community research. Health Can Soc. 1996; 4:29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Druss RG, Douglas CJ. Adaptive responses to illness and disability. Healthy denial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988; 10:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006; 91:730–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000; 71:543–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yehuda R, Flory JD. Differentiating biological correlates of risk, PTSD, and resilience following trauma exposure. J Traum Stress. 2007; 20:435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonanno G. Psychological resilience after disaster: New York City in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attack. Psychol Sci. 2006; 17:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diehl M, Hay EL, Chui H. Personal risk and resilience factors in the context of daily stress. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 2012; 32:251–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazarus SL, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer Pub. Co.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almeida D, Neupart S, Banks S, Serido J. Do daily stress processes account for socioeconomic health disparities? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005; 60:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park ER, Traeger L, Vranceanu AM, et al. The development of a patient-centered program based on the relaxation response: The Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (3RP). Psychosomatics. 2013; 54:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hankin BL, Abela JRZ. Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheffer M, Bolhuis JE, Borsboom D, et al. Quantifying resilience of humans and other animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018; 115:11883–11890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inquiry. 2004; 15:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, Byers J. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2006; 29:103–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith-Osborne A, Whitehill Bolton K. Assessing resilience: a review of measures across the life course. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2013; 10:111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. J Appl Psychol. 2008; 57:660–680. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benson H, Greenwood MM, Klemchuk H. The relaxation response: psychophysiologic aspects and clinical applications. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1975; 6:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanez BR, Stanton AL, Hoyt MA, Tennen H, Lechner S. Understanding perceptions of benefit following adversity: how do distinct assessments of growth relate to coping and adjustment to stressful events? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011; 30:699–721. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996; 9:455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lechner SC, Whitehead NE, Vargas S, et al. Does a community-based stress management intervention affect psychological adaptation among underserved black breast cancer survivors? J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014; 2014:315–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park ER, Mutchler JE, Perez G, et al. Coping and resiliency enhancement program (CARE): a pilot study for interpreters in cancer care. Psychooncology. 2017; 26:1181–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vranceanu AM, Merker VL, Plotkin SR, Park ER. The relaxation response resiliency program (3RP) in patients with neurofibromatosis 1, neurofibromatosis 2, and schwannomatosis: results from a pilot study. J Neurooncol. 2014; 120:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park ER, Perez GK, Millstein RA. A virtual resiliency intervention promoting resiliency for parents of children with learning and attentional disabilities: a randomized pilot trial. Matern Child Health J. 2020; 24(1):39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carver CS. Measure of current status. http://www.psy.miami.edu/faculty/ccarver/sclMOCS.html. Published 2006. Accessed February 25, 2021.

- 52.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009; 114:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990; 28:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994; 67:1063–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54(6):1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu Y, Shiu CS, Yang JP, Wang M, Simoni JM, Chen WT. Factor analyses of a social support scale using two methods. Qual Life Res. 2015; 24:787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual difference in empathy. JSAS Catal Select Doc Psychol.1980; 10:85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feldman G, Hayes A, Kumar S, Greeson J, Laurenceau JP. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: the development and initial validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2006; 29:177–190. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Field CA, Adinoff B, Harris TR, Ball SA, Carroll KM. Construct, concurrent and predictive validity of the URICA: data from two multi-site clinical trials. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009; 101:115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990; 107:238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bredle JM, Salsman JM, Debb SM, Arnold BJ, Cella D. Spiritual well-being as a component of health-related quality of life: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Religions. 2011; 2(1):77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deshields TL, Heiland MF, Kracen AC, Dua P. Resilience in adults with cancer: development of a conceptual model. Psychooncology. 2016; 25:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hall DL, Park ER, Cheung T, Davis RB, Yeh GY. A pilot mind-body resiliency intervention targeting fear of recurrence among cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res. 2020; 137:110215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lechner SC, Weaver K. Lessons learned about benefit finding among individuals with cancer or HIV/AIDS. In: CL Park, SC Lechner, MH Antoni, AL Stanton, eds. Medical Illness and Positive Life Change: Can Crisis Lead to Personal Transformation? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009:107–124. [Google Scholar]