SUMMARY

Phosphoinositides are important molecules in lipid signaling, membrane identity, and trafficking that are spatiotemporally controlled by factors from both mammalian cells and intracellular pathogens. Here, using small interfering RNA (siRNA) directed against phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatases, we screen for regulators of the host innate defense response to intracellular bacterial replication. We identify SAC1, a transmembrane phosphoinositide phosphatase, as an essential regulator of xenophagy. Depletion or inactivation of SAC1 compromises fusion between Salmonella-containing autophagosomes and lysosomes, leading to increased bacterial replication. Mechanistically, the loss of SAC1 results in aberrant accumulation of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate [PI(4)P] on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes, thus facilitating recruitment of SteA, a PI(4)P-binding Salmonella effector protein, which impedes lysosomal fusion. Replication of Salmonella lacking SteA is suppressed by SAC-1-deficient cells, however, demonstrating bacterial adaptation to xenophagy. Our findings uncover a paradigm in which a host protein regulates the level of its substrate and impairs the function of a bacterial effector during xenophagy.

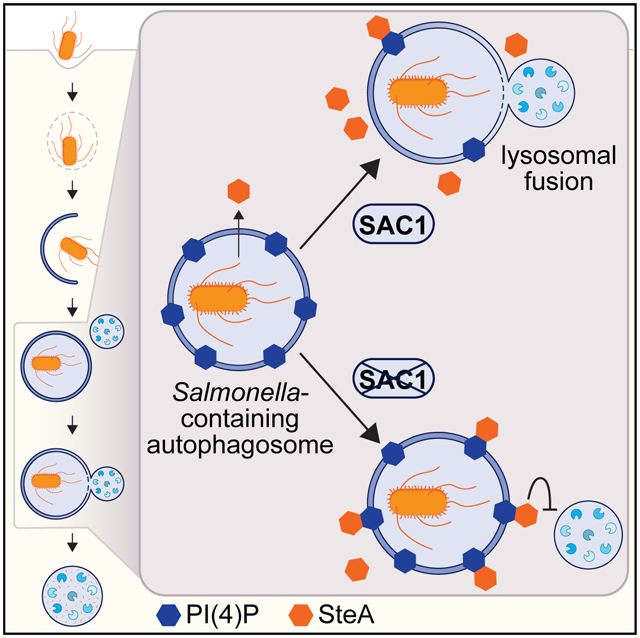

Graphical Abstract

In brief

Liu et al. reveal that a mammalian protein regulates levels of its substrate, impairing the function of a bacterial effector during xenophagy. The authors demonstrate that SAC1 restricts intracellular bacterial replication by controlling PI(4)P on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes and preventing recruitment of the Salmonella-secreted effector SteA, which interferes with lysosomal fusion.

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy is a sequential, highly regulated catabolic process that maintains cellular homeostasis and is further induced in response to internal or external cues (Bento et al., 2016; Clarke and Simon, 2019; Levine and Kroemer, 2008). Evolutionarily conserved autophagy genes coordinate to form a double-membraned autophagosome that engulfs content and fuses with lysosomes for degradation (Levine and Kroemer, 2008). Damaged organelles, protein aggregates, or intracellular pathogens are targeted for degradation through selective autophagy mechanisms (Gatica et al., 2018; Zaffagnini and Martens, 2016). The specificity of selective autophagy in higher eukaryotes is largely conferred by soluble autophagy cargo receptors including SQSTM1, NDP52, TAX1BP1, OPTN, and NBR1 (Gatica et al., 2018; Kirkin and Rogov, 2019). These receptors tether cargo to nascent autophagosomes by simultaneously binding cargo and LC3 family proteins through an LC3-interacting motif (Kim et al., 2016). Cargo is commonly ubiquitinated and bound by receptors through ubiquitin-binding domains (Deosaran et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2012; Mancias et al., 2014; Thurston et al., 2012).

Selective autophagy for the clearance of intracellular pathogens, known as xenophagy, is an important innate defense response, and Salmonella serves as a model bacteria susceptible to this defense mechanism (Benjamin et al., 2013; Birmingham et al., 2006; Conway et al., 2013; Huang and Brumell, 2014). Following invasion into a mammalian cell, Salmonella reside in Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCVs), which are actively remodeled by bacteria to facilitate replication (Castanheira and García-Del Portillo, 2017; Kehl et al., 2020; Tuli and Sharma, 2019). If SCV membrane integrity is compromised or bacteria escape the vacuole, host autophagy machinery recognizes either damaged SCVs or cytosolic bacteria. Damaged SCVs are detected by galectin family proteins that bind lumenal glycan moieties and mark the membrane for autophagic degradation by direct interaction with cargo receptors (Paz et al., 2010; Thurston et al., 2012). Cytosolic Salmonella are ubiquitinated by E3 ligases and bound by cargo receptors by a ubiquitin-binding motif (Heath et al., 2016; Huett et al., 2012; Polajnar et al., 2017; Shaid et al., 2013). Once targeted to intracellular bacteria, NDP52, a xenophagy cargo receptor, initiates autophagy by recruiting the ULK complex, which activates phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PIK3C3) to generate phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate [PI(3)P] (Ravenhill et al., 2019; Vargas et al., 2019). This recruits effectors, such as WIPI proteins, to autophagosomal membranes (Nakatogawa, 2020; Polson et al., 2010) followed by LC3 and the lipidation machinery complex that facilitates full encapsulation of bacteria within autophagosomes (Kimmey and Stallings, 2016; Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). Clearance of autophagosomal content, including LC3 and cargo receptors, follows fusion with lysosomal compartments containing degradative enzymes (Birmingham et al., 2006; Sharma et al., 2018).

As mammalian cells use xenophagy to eliminate intracellular pathogens, bacteria evolved strategies to manipulate or abrogate host cell processes for survival (Gomez-Valero et al., 2019; Huang and Brumell, 2014; Schroeder, 2018; Xiao and Cai, 2020). Streptococcus pyogenes expresses a cysteine protease SpeB to evade autophagic recognition by degrading SQSTM1 and NDP52 (Barnett et al., 2013). Listeria monocytogenes and Legionella pneumophila secrete enzymes targeting LC3 to prevent lipidation and conjugation of autophagosomal membranes (Choy et al., 2012; Horenkamp et al., 2015; Kubori et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2018; Tattoli et al., 2013). Salmonella secretes effector proteins including SopF, which inhibits the association between ATG16L1 and the vacuolar ATPase component ATP6V0C, thus blocking ATG16L1 and LC3 recruitment and xenophagy initiation (Lau et al., 2019; Mesquita et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2019).

Pathogens also exploit membrane trafficking to establish and maintain replication-competent niches in the host cytosol. Phosphoinositides are key components of cellular membranes essential for spatiotemporal regulation of trafficking. Seven phosphorylated forms of phosphoinositide are critical for cellular physiology and membrane identity, and interconversion between these forms is tightly controlled by lipid kinases and phosphatases (Dall’Armi et al., 2013; Nakada-Tsukui et al., 2019). Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate [PI(4)P], found on Golgi, endosomes, and plasma membranes, has important signaling roles in trafficking (Santiago-Tirado and Bretscher, 2011), phagolysosome resolution (Levin-Konigsberg et al., 2019), inflammasome formation (Chen and Chen, 2018), and autophagy (de la Ballina et al., 2020; De Tito et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2015; Yamashita et al., 2006). In humans, PI(4)P homeostasis is coordinately maintained by four membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol-4 kinases (PI4Ks) and a single conserved PI(4)P phosphatase, SAC1 (Clayton et al., 2013; Del Bel and Brill, 2018; Liu et al., 2009; Venditti et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2013). Interestingly, L. pneumophila secretes lipid kinases (LepB) and phosphatases (SidC and SidF) capable of regulating PI(4)P levels on Legionella-containing vacuolar membranes as well as phosphoinositide-binding proteins that localize to Legionella-containing vacuoles (Hubber et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2015; Nachmias et al., 2019; Wasilko and Mao, 2016; Weber et al., 2018).

The role of lipid membrane composition in selective autophagy, however, is largely unknown. In this study, we completed a targeted small interfering RNA (siRNA) screen to find lipid kinases and phosphatases functioning in bacterial autophagy. We identified the PI(4)P phosphatase SAC1, encoded by human SACM1L, as an essential regulator of Salmonella-induced xenophagy. Our data demonstrate that the control of PI(4)P levels on autophagosomal membranes by SAC1 is required for efficient intracellular bacterial defense. We found that elevated PI(4)P levels on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes in SACM1L-deficient cells delays fusion with lysosomes. Furthermore, we showed that the Salmonella type III secreted effector and PI(4) P-binding protein SteA promotes intracellular bacterial replication by impeding clearance through xenophagy. Collectively, our results reveal counter-regulation of lipid membrane dynamics by mammalian host cells and bacteria during xenophagy to modulate an innate defense response.

RESULTS

Lipid enzymes function in intracellular bacterial replication

We performed a directed siRNA screen to investigate the specific roles of membrane phosphoinositides in host bacterial defense. We targeted 67 known human lipid kinase and phosphatase genes by using three independent siRNA molecules per gene and evaluated transfected HeLa cells for changes in replication of bioluminescent Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium at 8.5 h post-infection relative to non-targeting siRNA controls (Figure 1A; Table S1; Dickson and Hille, 2019; Sacco et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2009). Knockdown of PIK3C3, which is required to generate PI(3)P for nucleation of the autophagosomal membrane (Simonsen and Tooze, 2009; Yue and Zhong, 2010), increased intracellular bacterial replication compared to controls, as expected, and served as a positive control (Figure 1A). SACM1L was the only additional gene in our screen required to restrict intracellular bacterial replication.

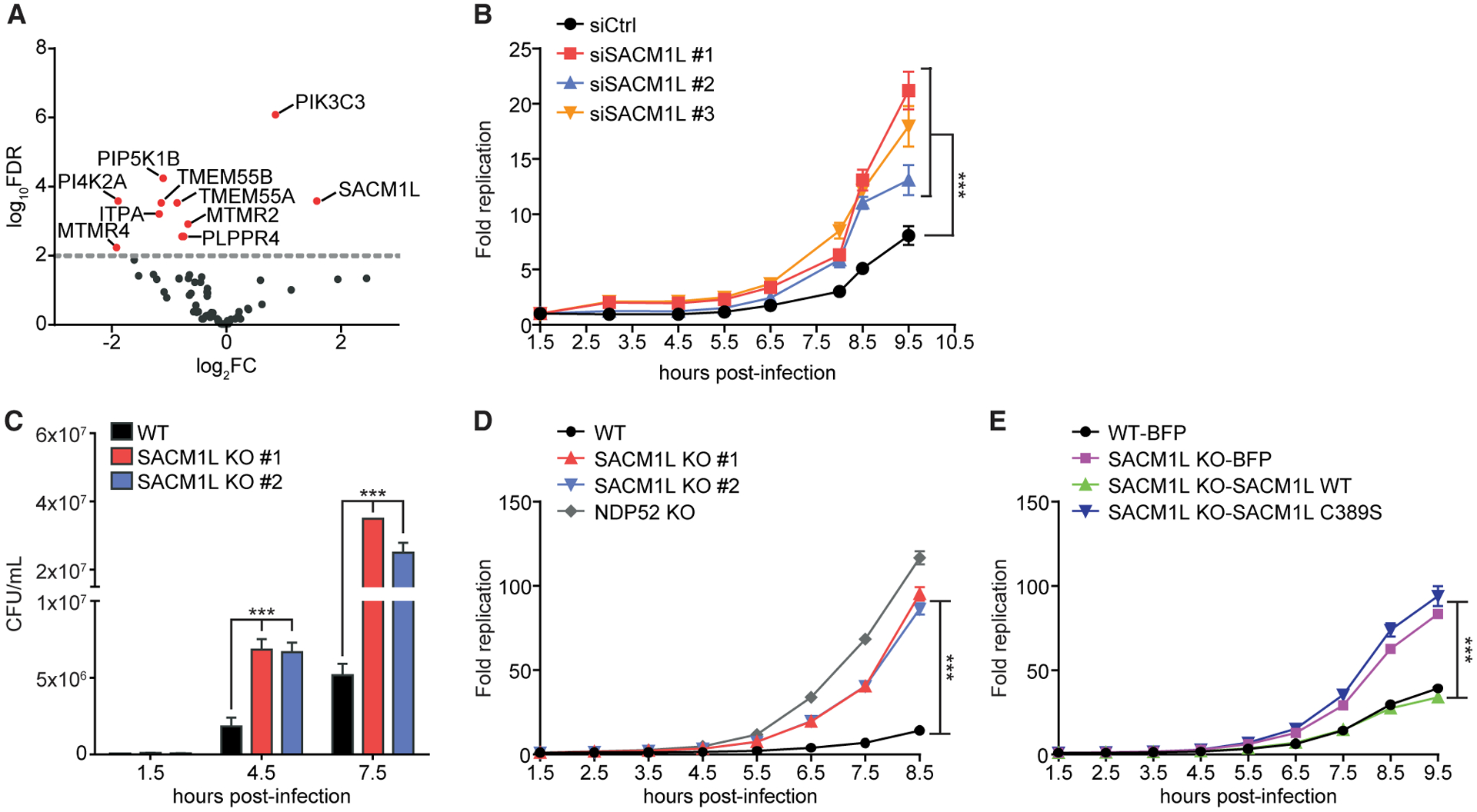

Figure 1. SAC1 restricts intracellular bacterial replication.

(A) Volcano plot of siRNA screen shows log2 fold change (log2FC) of Salmonella replication compared with that of control siRNA. Data represent combined analysis from three independent experiments. Red dots indicate genes with false discovery rate (FDR) values of <0.01.

(B) HeLa cells transfected with control (Ctrl) or one of three independent SACM1L-directed siRNA molecules were infected with Salmonella expressing bacterial luciferase. Luciferase levels were measured over time. Bacterial replication was normalized to baseline infection at 1.5 h post-infection.

(C) CFU/mL of Salmonella at indicated times after infection of WT or SACM1L KO cells.

(D) Fold change of luciferase-expressing Salmonella replication in WT, SACM1L KO, and NDP52 KO cells

(E) WT cells stably expressing BFP and SACM1L KO cells stably expressing BFP, SACM1L WT, or SACM1L C389S were infected with luciferase-expressing Salmonella. Luciferase levels were measured over time. Bacterial replication was normalized to baseline infection at 1.5 h post-infection. For all quantifications, three independent experiments were analyzed using ANOVA (mean ± SEM [standard error of the mean]). ***p < 0.001.

We also identified phosphoinositide regulators that supported intracellular replication including MTMR4, a PI(3)P phosphatase required for vesicular trafficking and maturation of endocytic and autophagic compartments (Pham et al., 2018; Figure 1A). In agreement with our data, previous reports demonstrated that expression of MTMR4 supports Salmonella replication by maintaining PI(3)P levels and stabilizing SCVs (Teo et al., 2016). Several other genes identified have no known activity in bacterial defense (TMEM55A, TMEM55B, PLPPR4, and PI4K2ɑ). TMEM55A and TMEM55B are PI(4,5)P2 phosphatases that localize to late endosomal and lysosomal membranes (Morioka et al., 2018). Previous studies revealed that TMEM55B is controlled by TFEB, a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis, and functions in lysosomal positioning (Hashimoto et al., 2018; Takemasu et al., 2019; Willett et al., 2017). Production of PI(4)P by PI4K2ɑ, one of four human PI4Ks, has been implicated in autophagosome-lysosomal fusion (Albanesi et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Knockdowns of the other human PI4Ks (PI4Kɑ, PI4Kβ, and PI4K2β) did not significantly modulate Salmonella replication (Table S1).

Of the lipid kinases and phosphatases screened, PI4K2ɑ and SAC1 were the only enzymes found that catalyze opposing reactions on the same substrate. As SACM1L is evolutionarily conserved across eukaryotic cells and the only PI(4)P-specific phosphatase in humans (Zhang et al., 2020), we focused our investigations on its role in restricting intracellular bacterial replication. To maintain a synchronous infection, the window for infections throughout our study was limited to 30 min (unless otherwise stated), after which cells were immediately analyzed or washed and treated with gentamicin to prevent further infection by the remaining extracellular bacteria. Time post-infection designates the time elapsed from the beginning of the infection period. We first confirmed the knockdown phenotype in an independent experiment by using three SACM1L targeting and non-targeting control siRNA molecules. Cells transfected with each of the individual SACM1L-targeting siRNA molecules were defective in restricting Salmonella replication as compared to control cells (Figure 1B).

SAC1 phosphatase activity is required for restricting bacterial replication

To validate our siRNA knockdown results, we generated SACM1L knockout (KO) HeLa cell lines by using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Two independent SACM1L KO clones showed no detectable SAC1 expression by immunoblot and immunofluorescence microscopy and exhibited dispersion of the trans-Golgi network as previously reported (Liu et al., 2008; Figures S1A and S1B). With these SACM1L KO clones, we performed two independent Salmonella replication assays. Wild-type (WT) cells infected with S. Typhimurium SL1344 or an SL1344 strain expressing luciferase restricted intracellular replication as measured by colony-forming units (CFUs) and bioluminescence intensity, respectively (Figures 1C and 1D; Conway et al., 2013; Hoiseth and Stocker, 1981). Similar to NDP52 KO cells, robust bacterial replication was observed in cells lacking SAC1, confirming SACM1L KO cells reproduce the SACM1L knockdown phenotype (Figures 1C and 1D).

To verify that disruption to SACM1L specifically was responsible for the defect in bacterial replication restriction and to control for off-target effects, we re-expressed the SAC1 WT protein or blue fluorescent protein (BFP) control in SACM1L KO cells. Expression of SAC1 WT in SACM1L KO and WT cell lines was confirmed by immunoblot (Figure S1A). SACM1L KO cells reconstituted with SAC1 WT restricted bacterial replication to a level similar to that of WT cells expressing BFP (Figure 1E). These data establish that the loss of SAC1 is responsible for increased bacterial replication. Furthermore, to determine if SAC1 phosphatase activity was required for bacterial growth restriction, we substituted the catalytic cysteine residue with serine and reconstituted SACM1L KO cells with the catalytically dead SAC1 C389S mutant (Liu et al., 2009). SAC1 C389S expression was confirmed by immunoblot and comparable to SAC1 WT levels (Figure S1A). Expression of SAC1 C389S did not rescue the SACM1L KO phenotype, indicating SAC1 phosphatase activity is required for restricting intracellular bacterial replication (Figure 1E).

SAC1 does not affect basal or non-selective autophagic flux nor lysosomal function

Next, we interrogated the role of SAC1 in innate defense mechanisms used to restrict bacterial replication by examining the effect of SAC1 expression on autophagy and autophagic flux. The ratio of membrane-bound LC3II to cytosolic LC3I, which corresponds to autophagosome formation, was consistent between WT and SACM1L KO cells under basal conditions as well as in response to treatment with the autophagy-inducing small molecule Torin1 or lysosomal inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1; Figures 2A and 2B). Additionally, no difference was detected in the LC3I to LC3II conversion in WT, SACM1L KO, or reconstituted cells at steady state or in response to amino acid starvation (Figures S2A and S2B). SQSTM1 protein levels in both WT and SACM1L KO cells decreased in response to Torin1 and increased upon treatment with BafA1 alone or in combination with Torin1, indicating that the loss of SAC1 did not alter basal or non-selective autophagy (Figures 2A and 2B).

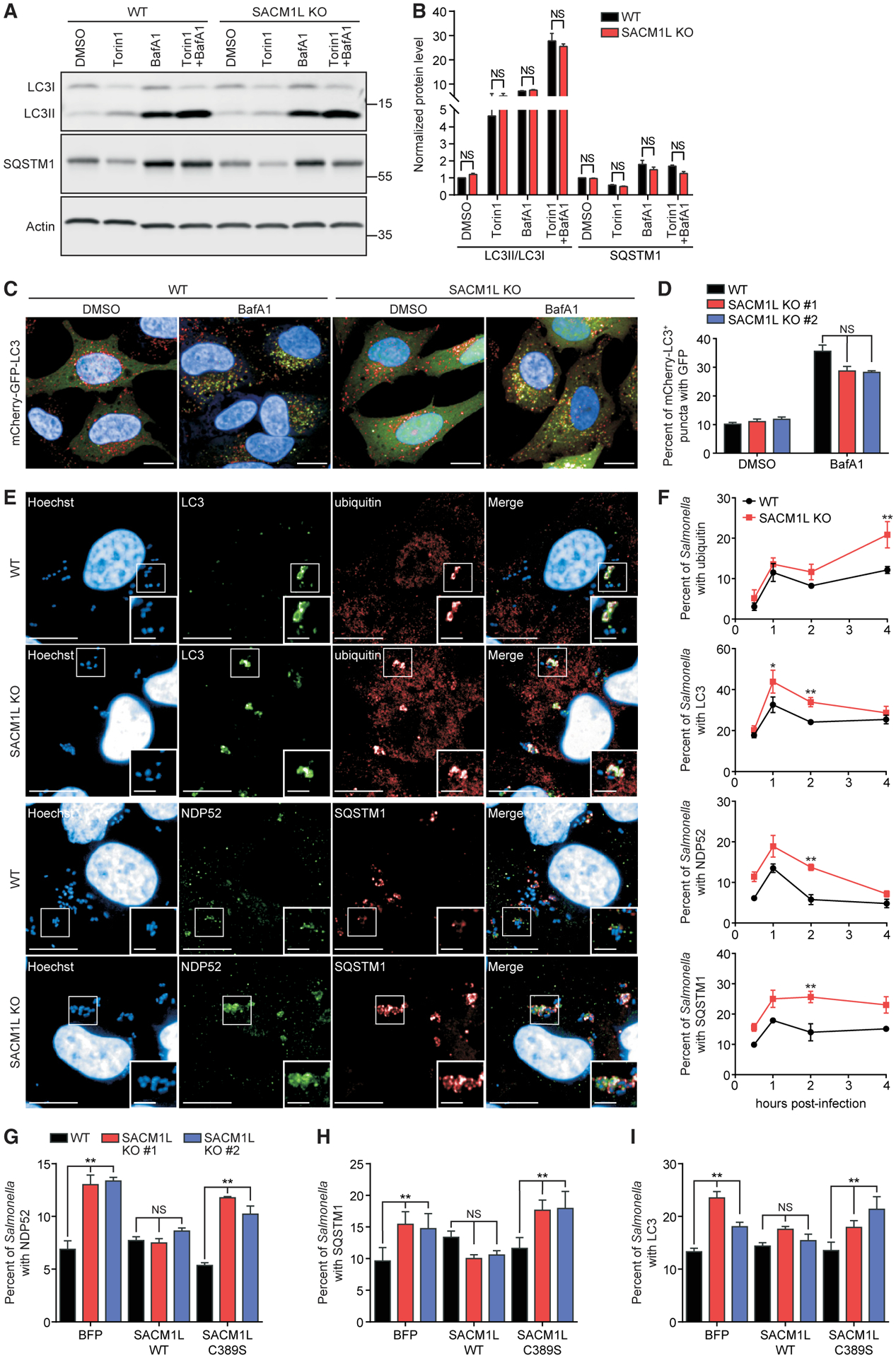

Figure 2. SAC1 activity regulates maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes.

(A and B) Representative immunoblot (A) and quantification (B) of LC3 conversion and SQSTM1 in WT and SACM1L KO cells treated with 0.1% DMSO, 1 μM Torin1, 200 ng/ml BafA1, or a combination of Torin1 and BafA1 for 4 h. Quantification of LC3II/LC3I ratio or SQSTM1 protein was normalized to DMSO-treated WT cells.

(C and D) Representative confocal images (C) and quantification (D) of mCherry-GFP-LC3 expression in WT and SACM1L KO cells treated with DMSO or BafA1 for 4 h. Scale bars represent 20 μm.

(E and F) Representative confocal images (E) and quantifications (F) of Salmonella associated with endogenous ubiquitin, LC3, NDP52, and SQSTM1 in WT and SACM1L KO cells at indicated times post-infection. Images were captured at 2 h post-infection. Insets are boxed regions magnified (1.8×). Hoechst shows HeLa cell nuclei and Salmonella. Scale bars represent 20 μm in full images and 5 μm in insets.

(G–I) Percentage of Salmonella associated with endogenous NDP52 (G), SQSTM1 (H), or LC3 (I) in WT and SACM1L KO cells stably expressing BFP, SACM1L WT, or SACM1L C389S at 2 h post-infection. For all quantifications, over 500 cells were analyzed. Three independent experiments were analyzed using ANOVA (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; NS, not significant.

See also Figure S2.

We then generated WT and SACM1L KO cells that stably express a tandem mCherry-GFP-LC3 reporter to determine if SAC1 alters autophagosome maturation. Because GFP fluorescence is quenched in acidic lysosomal compartments, mCherry+GFP+ vesicles represent immature autophagosomes, whereas mCherry+GFP− vesicles reveal acidified autolysosomes (Hansen and Johansen, 2011). By quantitative microscopy, we found that the percentage of immature autophagosomes and autolysosomes did not change significantly in SACM1L KO compared to WT cells treated with DMSO or BafA1 (Figures 2C and 2D). Lysosomal number, indicated by the intensity of pH-sensitive LysoTracker dye, and function, measured by hydrolyzed DQ-green BSA, were also unchanged in SACM1L KO cells (Figures S2C and S2D). These results indicate that SAC1 loss does not alter steady-state or induced non-selective autophagic flux, autophagosome maturation, or lysosomal function.

SAC1 phosphatase activity is required for functional xenophagy

Considering that SAC1 loss did not interfere with non-selective autophagy or lysosomal function, we investigated if SAC1 restricts intracellular bacterial replication through a xenophagy-specific role. We examined the effect of SAC1 expression on bacterial targeting by key xenophagy markers by using time-dependent quantitative confocal imaging. As intracellular bacteria are recognized, host xenophagy machinery, including ubiquitin, cargo receptors (NDP52 and SQSTM1), galectins (Gal3), and isolation membranes (marked by LC3), are recruited and associate with bacteria by 1 h post-infection (Paz et al., 2010; Thurston et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2019). By 2 h post-infection, xenophagy markers are degraded by lysosomal fusion, and detectable associations with bacteria decline to steady-state levels. A higher percentage of Salmonella was associated with endogenous LC3, NDP52, and SQSTM1 at 2 h post-infection in SACM1L KO cells than in WT cells, suggesting a delay in Salmonella-containing autophagosome maturation (Figures 2E and 2F). Consistent with these data, we observed a slower rate of NDP52 degradation after Salmonella infection in SACM1L KO by immunoblot analysis (Figures S2E and S2F). Although levels of SQSTM1 associated with bacteria were elevated, no delay in total cellular SQSTM1 turnover was detected (Figures S2E and S2G). In contrast, loss of SAC1 did not alter the percentage of bacteria that co-localized with endogenous ubiquitin, LC3, NDP52, or SQSTM1 at earlier times (0.5 h and 1 h post-infection), indicating that SAC1 does not function in the recognition or assembly of autophagy machinery around intracellular Salmonella (Figure 2F).

Changes in membrane composition by knockdown of OSBP1, a PI(4)P- and cholesterol-binding protein that interacts with Salmonella effectors SseJ and SseL for recruitment to the SCV, were reported to destabilize SCV membranes (Kolodziejek et al., 2019). We monitored the dynamic recruitment of GFP-tagged Gal3 to intracellular dsRed-expressing Salmonella (Maejima et al., 2013; Rioux et al., 2007) but did not detect differences in co-localization in WT and SACM1L KO cells, suggesting that the loss of SAC1 does not affect SCV integrity at 1 h post-infection (Figures S2H and S2I). These data, in addition to the observed defect in the restriction of bacterial replication (Figure 1), suggest that SAC1 loss delays the maturation of autophagosomes and degradation of Salmonella targeted by xenophagy cargo receptors. Furthermore, re-expression of SAC1 WT, but not SAC1 C389S or BFP, reduced the levels of NDP52+, SQSTM1+, and LC3+ Salmonella in SACM1L KO cells at 2 h post-infection (Figures 2G–2I), revealing that SAC1 phosphatase activity is necessary for functional xenophagy.

To determine if SAC1 functions in other types of selective autophagy, we induced mitophagy or aggrephagy in WT and SACM1L KO cells. Similar to xenophagy, Parkin-mediated mitophagy uses NDP52 as a cargo receptor to clear damaged mitochondria (Heo et al., 2015; Lazarou et al., 2015). WT and SACM1L KO cells expressing Parkin were treated with either carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) or a combination of oligomycin and antimycin A to induce mitochondrial depolarization (Yamano et al., 2014). As detected by TOMM20, a mitochondrial outer membrane protein, both WT and SACM1L KO cells efficiently cleared damaged mitochondria (Figures S2J and S2K). Similarly, SACM1L WT and KO cells treated for 2 h with puromycin, an amino acid analog that induces protein aggregates by prematurely terminating translation, effectively cleared ubiquitin+ aggregates after 3-h and 5-h periods of recovery (Figures S2L–S2N). As previously shown in response to a loss of other autophagy cargo receptors, SACM1L KO cells formed fewer and smaller puromycin-induced aggregates (Bjørkøy et al., 2005; Sarraf et al., 2020), but there was no effect on the rate of clearance (Figures S2O and S2P). These results indicate that SAC1 is not required for Parkin-mediated mitophagy or aggrephagy but rather functions specifically in xenophagy.

SAC1 promotes the maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes

Next, we examined which step in xenophagy is modulated by SAC1. Using the WT and SACM1L KO mCherry-GFP-LC3 reporter cell lines described above, we monitored the maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes by live cell imaging. CellTracker-labeled Salmonella were detected first in mCherry+GFP+ autophagosomes, which gradually converted to mCherry+GFP− autolysosomes. In WT cells, only 17% of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes were immature at 2 h post-infection (Figures 3A and 3B). In contrast, 30% of Salmonella remained in mCherry+GFP+ autophagosomes in SACM1L KO cells, suggesting that the loss of SAC1 delays maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes (Figures 3A and 3B).

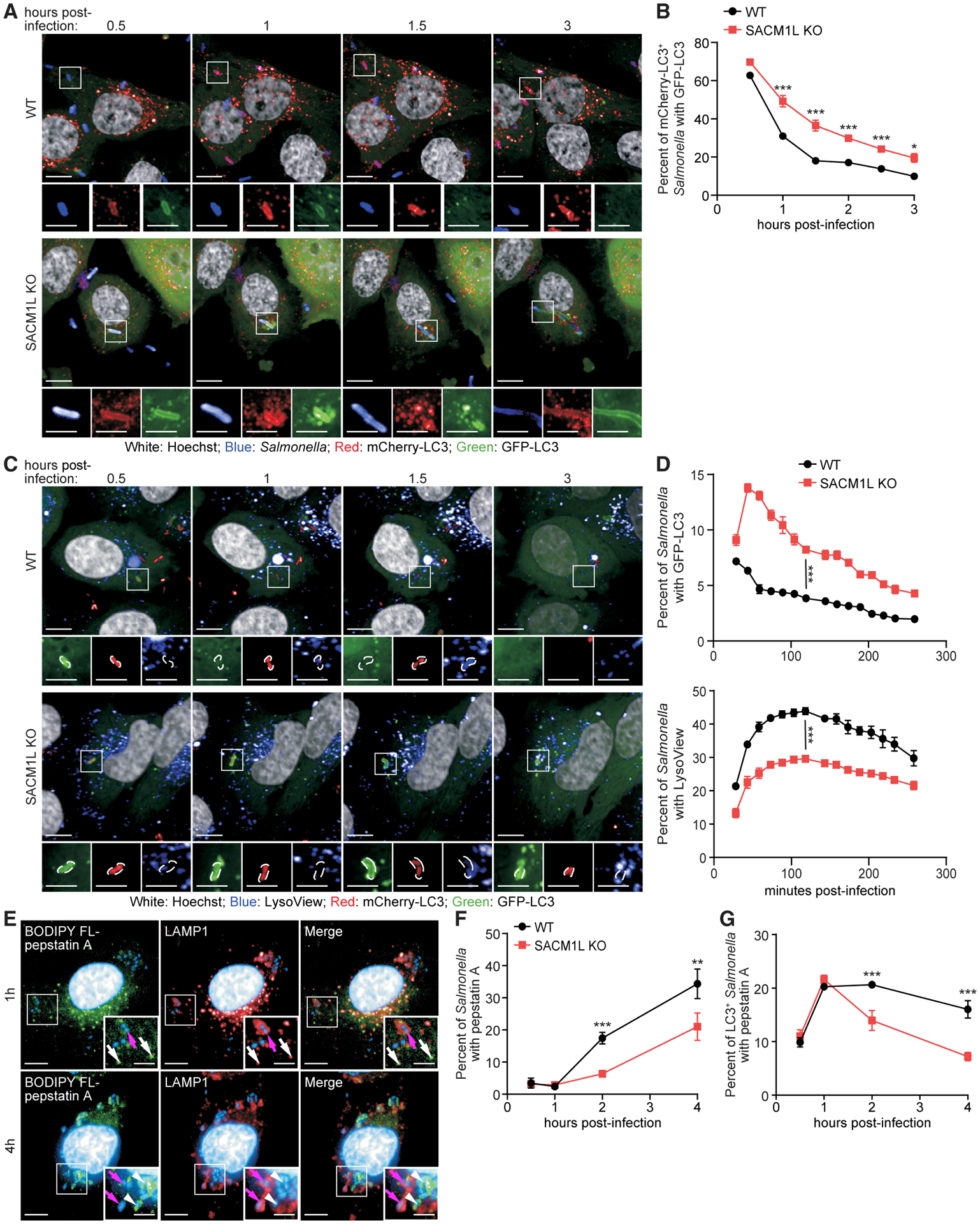

Figure 3. SAC1 loss impairs lysosomal fusion.

(A and B) WT and SACM1L KO cells stably expressing mCherry-GFP-LC3 were stained with Hoechst, infected with Salmonella labeled with CellTracker deep red dye, washed, imaged by live confocal microscopy (A), and quantified (B). Percentage of GFP-LC3+ Salmonella-containing autophagosomes is shown at indicated times post-infection.

(C and D) WT and SACM1L KO cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were infected with dsRed-expressing Salmonella and stained with LysoView 633 dye and Hoechst. Live confocal microscopy images (C) and percentage (D) of Salmonella positive for GFP-LC3 (top) or LysoView dye (bottom) are shown. Magnified images (2.4×) show separated channels of the boxed region in merged images. Scale bars represent 10 μm in merged images and 5 μm in magnified images.

(E) Co-immunostaining of BODIPY FL-pepstatin A, LAMP1, and Hoechst in WT cells at 1 h and 4 h post-infection. Insets are boxed regions magnified (1.8×). Scale bars represent 10 μm in full images and 5 μm in insets. Magenta arrows indicate LAMP1+pepstatin A− Salmonella. White arrows (1-h image insets) indicate pepstatin A+ lysosomes. White arrowheads (4-h image insets) indicate pepstatin A+ Salmonella.

(F and G) Percentage of Salmonella (F) or LC3+ Salmonella (G) associated with pepstatin A in WT and SACM1L KO cells at indicated times post-infection. For all quantifications, over 500 cells were analyzed for each condition. Three independent experiments were analyzed using ANOVA (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

See also Figure S3.

To determine if this defect was due to SAC1 loss impeding the closure of autophagosomal membranes, we monitored the recruitment and removal of endogenous WIPI2 on LC3+ Salmonella. WIPI2 functions in conjunction with LC3 to expand isolation membranes and dissociates from LC3+ membranes prior to autophagosome closure (Dooley et al., 2014; Fracchiolla et al., 2020). In both WT and SACM1L KO cells, WIPI2 was efficiently recruited to LC3+ Salmonella and then gradually disappeared, as demonstrated by the decreasing percentage of WIPI2+LC3+ among all LC3+ Salmonella over time (Figures S3A and S3B). These data indicate that SAC1 is not required for the formation and closure of autophagosomes around Salmonella.

To directly assess the fusion of acidic compartments with Salmonella-containing autophagosomes, we simultaneously monitored Salmonella, GFP-LC3, and lysosomes stained with a pH-sensitive LysoView dye. In WT cells, GFP-LC3 co-localized with Salmonella at 30 min post-infection, and the loss of detectable GFP-LC3+ Salmonella was coordinated with the increase of LysoView dye associated with bacteria, reflecting degradation of GFP-LC3 upon fusion with lysosomes (Figures 3C and 3D). In SACM1L KO cells, a higher percentage of Salmonella was associated with GFP-LC3 at all times (Figure 3D). Furthermore, only 30% of Salmonella was localized to LysoView+ acidic compartments in SACM1L KO cells at 120 min post-infection as compared to 44% in WT cells, confirming that SAC1 loss delays the fusion of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes with lysosomes (Figures 3D).

We then used BODIPY FL-pepstatin A, which selectively binds to active cathepsin D within lysosomes to detect the delivery of lysosomal enzymes to Salmonella-containing autophagosomes (Chen et al., 2000). As expected, most Salmonella bacteria in WT cells were found residing within LAMP1+pepstatin A− vacuoles at 1 h post-infection (Figures 3E and 3F; Birmingham et al., 2006(Zoncu et al., 2011)). By 2 h post-infection, Salmonella targeted by xenophagy machinery in WT cells progressed to LAMP1−pepstatin A+ compartments, indicating that active lysosomes fused with Salmonella-containing autophagosomes (Figure 3F). In contrast, the loss of SAC1 reduced the delivery of lysosomal enzymes to Salmonella-containing autophagosomes, as reflected by the lower percentage of bacteria with pepstatin A (Figure 3F) as well as the lower percentage of LC3+pepstatin A+ Salmonella in SACM1L KO cells (14%) than in WT cells (21%) by 2 h post-infection (Figure 3G). This result was further validated using a MagicRed assay, which reflects cathepsin B activity, and DQ-BSA, which indicates the cleavage capacity of lysosomal hydrolases. The percentages of both MagicRed+ and DQ-BSA+ Salmonella by 2 h post-infection were lower in SACM1L KO cells than in WT cells (Figures S3C–S3F). Collectively, these results indicate that SAC1 promotes fusion of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes with lysosomes.

SAC1-dependent maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes reduces cytosolic bacterial replication

Not all Salmonella bacteria are captured by autophagosomes in epithelial cells; some replicate within SCVs or escape SCVs and replicate within the host cytosol (Castanheira and García-Del Portillo, 2017). To evaluate Salmonella existing within these compartments, we monitored WT and SACM1L KO cells co-expressing GFP-LC3 (marking autophagosomes) and LAMP1-mCherry (marking SCVs) by live cell imaging for 6 h post-infection (Lane et al., 2019; Valdivia and Falkow, 1996). In WT cells, we observed instances in which a reduction in LAMP1 signal detected on bacteria corresponded with an increase in LC3 signal (Figure 4A). Subsequently, the LC3 signal diminished and the LAMP1 signal increased as the bacterial morphology condensed. These results suggest that bacteria can escape LAMP1+ SCVs and be targeted and degraded through xenophagy. In SACM1L KO cells, we observed bacteria that were targeted by autophagy machinery, as detected by GFP-LC3, but did not accumulate LAMP1 (Figure 4A). These bacteria then began to lose detectable GFPLC3 and rapidly divide in the host cytosol. Similar bacterial populations were not observed in WT cells, suggesting that a delay in Salmonella-containing autophagosome maturation due to SAC1 loss may facilitate bacterial escape and replication in the cytosol and contribute to the increased replication phenotype. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that SAC1 loss also affects SCV stability, leading to bacterial escape.

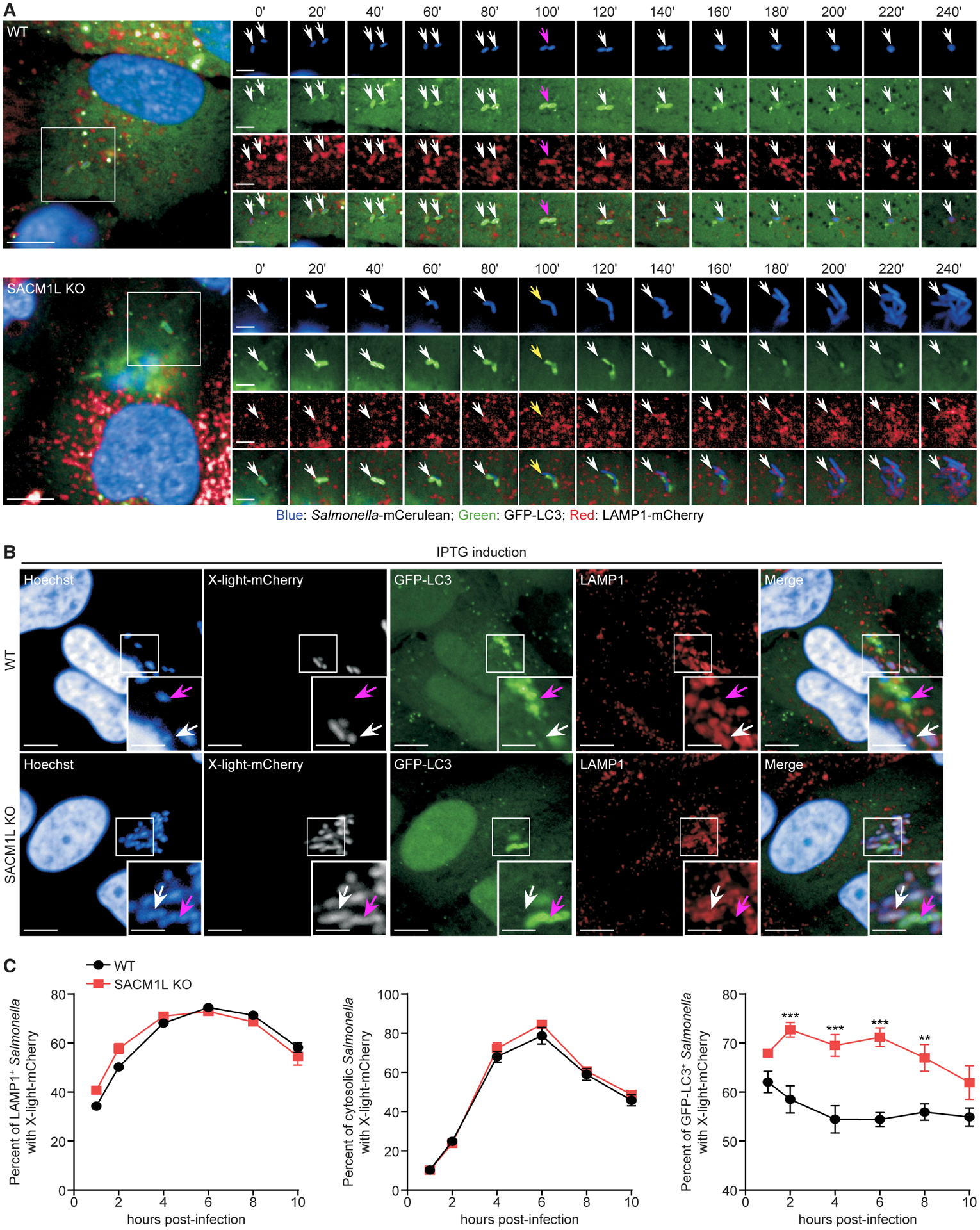

Figure 4. SAC1 loss impairs the ability of autophagosomes to restrict Salmonella replication.

(A) WT and SACM1L KO cells stably transduced with GFP-LC3 and LAMP1-mCherry were stained with Hoechst for 10 min, infected with mCerulean-expressing Salmonella for 15 min, washed, and imaged by live confocal microscopy every 20 min for 6 h. Timescale 0’ to 240’ is the minutes from detection of the bacteria in the cell and focal plane. White arrows indicate Salmonella. Magenta arrows (top) indicate peak GFP-LC3 intensity. Yellow arrows (bottom) show Salmonella escaping from autophagosomes prior to replicating in the host cytoplasm. Image series are boxed regions magnified (1.8×). Scale bars represent 10 μm in image series and 5 μm in full images.

(B) Representative confocal images of IPTG-induced mCherry expression in Salmonella within LAMP1+ (SCV) or GFP-LC3+ (autophagosome) compartments in WT and SACM1L KO cells at 6 h post-infection. Magenta arrows indicate GFP-LC3+ Salmonella. White arrows indicate LAMP1+ Salmonella. Insets are boxed regions magnified (2×). Scale bars represent 10 μm in full images and 5 μm in insets.

(C) Percentage of induced mCherry signal in LAMP1+, GFP-LC3−LAMP1−, (cytosolic), or GFP-LC3+ Salmonella in WT and SACM1L KO cells. For quantification, over 3,000 bacteria were analyzed. Two independent experiments were analyzed using ANOVA (mean ± SEM). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

See also Figure S4.

In a separate experiment, we quantitated LC3+, LAMP1+, and cytosolic LC3−LAMP1− bacteria in WT and SACM1L KO cells (Figure S4A). The percentage of cytosolic Salmonella increased and the percentage of LAMP1+ Salmonella decreased in SACM1L KO cells as compared to WT cells, supporting our live imaging observations. Additionally, the percentage of LC3+ Salmonella was higher in SACM1L KO cells than in WT cells at 2 h post-infection, which is indicative of a delay in autophagosomal maturation and LC3 turnover.

Next, we sought to determine the effect of SAC1 expression on the metabolic activity of Salmonella in autophagosomes, SCVs, and the host cytosol. We generated a Salmonella strain expressing an isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible mCherry plasmid (x-light-mCherry) as a reporter of metabolic activity (Sirianni et al., 2016). In the absence of IPTG induction, x-light-mCherry was not expressed by Salmonella (Figure S4B). When IPTG was added 30 min prior to fixation, the x-light-mCherry signal was detected in LC3+, LAMP1+, and cytosolic LC3−LAMP1− Salmonella (Figure 4B). Quantification of mCherry+LAMP1+ and mCherry+LC3−LAMP1− bacterial populations in WT and SACM1L KO cells indicated that the metabolic activity and survival of Salmonella in SCVs and the host cytosol are independent of SAC1 (Figure 4C). Consistent with our previous data, we detected a higher percentage of metabolically active Salmonella within LC3+ autophagosomes in SACM1L KO cells than in WT cells (Figure 4C), indicating a delay in bacterial killing.

To further support these findings, we treated infected WT and SACM1L KO cells with chloroquine, which accumulates and kills bacteria in SCVs (Knodler et al., 2014). In the absence of chloroquine, we observed robust Salmonella replication in SACM1L KO cells compared with that in WT cells (Figure S4C). Chloroquine treatment reduced the number of replicating bacteria in both WT and SACM1L KO cells but did not abolish the SAC1-dependent increase in bacterial replication. In addition to supporting a role for SAC1 in autophagosome maturation, these results suggest that the function of SAC1 in lysosomal fusion may impede Salmonella escape from immature autophagosomes.

SAC1 loss leads to excessive PI(4)P accumulation on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes

We next investigated how the known SAC1 substrate PI(4)P is regulated during xenophagy. We measured PI(4)P levels in WT and SACM1L KO cells at steady state and following infection. To specifically detect PI(4)P on subcellular membranes and organelles, we used a previously described fixation protocol that reduces the detection of PI(4)P on the plasma membrane (Hammond et al., 2009). As expected, SAC1 loss elevated PI(4)P levels in uninfected and infected cells (Figures 5A and 5B).

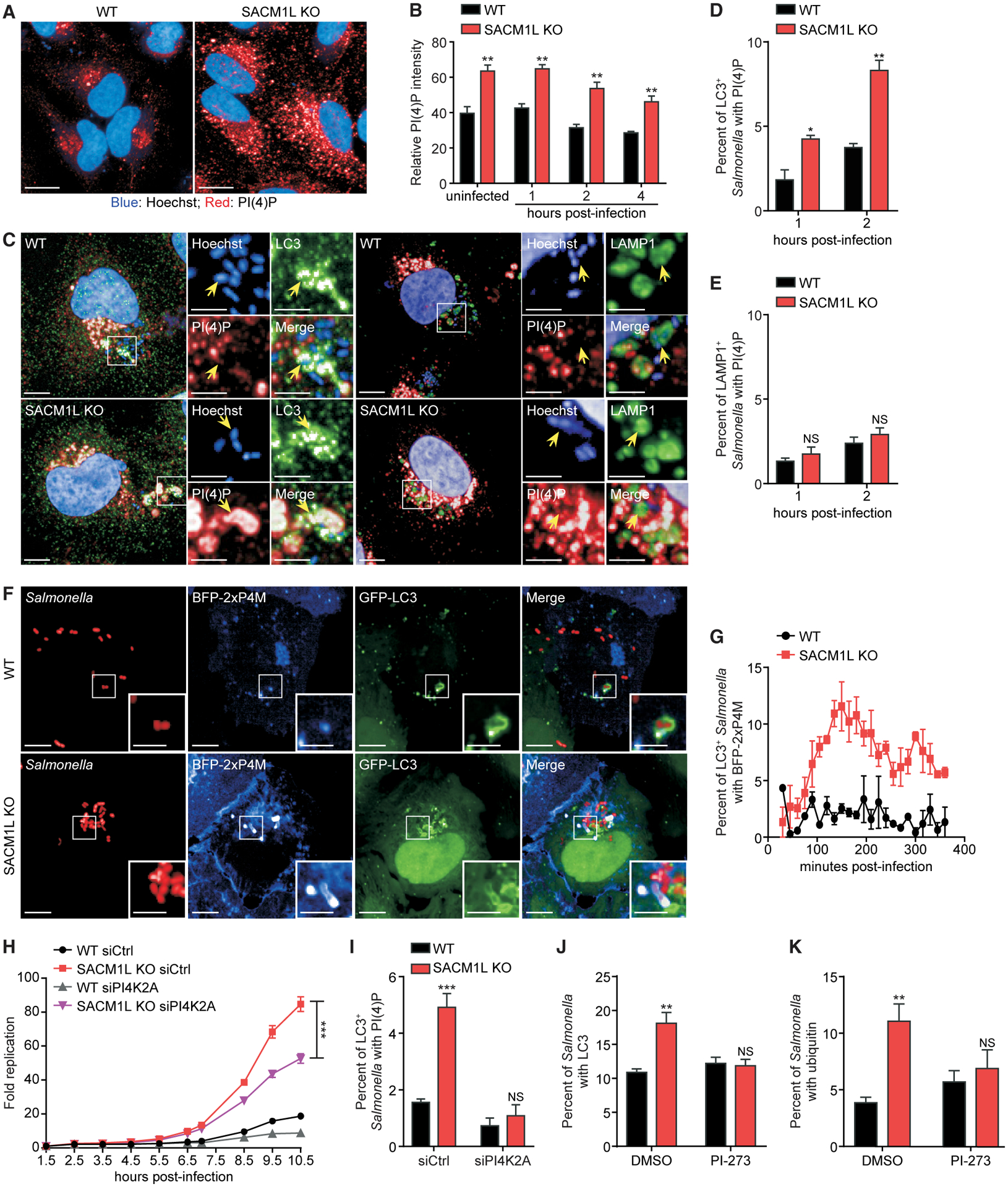

Figure 5. SAC1 regulates PI(4)P levels on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes.

(A) Immunostaining of endogenous PI(4)P in WT and SACM1L KO cells. Hoechst dye shows nuclei. Scale bars represent 20 μm.

(B) Relative PI(4)P staining intensity in uninfected or Salmonella-infected WT and SACM1L KO cells at indicated times post-infection.

(C) Representative confocal images of PI(4)P staining on endogenous LC3+ or LAMP1+ Salmonella in WT and SACM1L KO cells at 2 h post-infection. Insets are boxed regions magnified (2.8×). Hoechst dye shows nuclei and Salmonella. Scale bars represent 10 μm in full images and 5 μm in insets.

(D and E) Percentage of LC3+ (D) or LAMP1+ (E) Salmonella also positive for PI(4)P at indicated times post-infection. For quantification, over 2,000 bacteria were analyzed.

(F and G) Representative confocal images (F) and quantification (G) of co-localization of BFP-2xP4M and GFP-LC3+ Salmonella in WT and SACM1L KO cells. Insets are boxed regions magnified (2.5×). Scale bars represent 10 μm in full images and 5 μm in insets. Data were collected every 15 min for 6 h. For quantification, over 1,000 bacteria were analyzed.

(H) Fold change of luciferase-expressing Salmonella replication in WT and SACM1L KO cells transfected with control or PI4K2ɑ siRNA for 48 h prior to infection. Luciferase levels were measured over time. Bacterial replication was normalized to baseline infection.

(I) Percentage of LC3+ Salmonella associated with PI(4)P in WT and SACM1L KO cells transfected with control or PI4K2ɑ siRNA 48 h prior to infection.

(J and K) Percentage of Salmonella associated with LC3 (J) and ubiquitin (K) in WT and SACM1L KO cells pretreated with DMSO or PI4K2ɑ-specific inhibitor PI-273 (500 nM) for 1 h before infection, then fixed, and stained 2 h after infection. Unless indicated otherwise, over 500 cells were analyzed for quantification. Three independent experiments were analyzed using ANOVA (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; NS, not significant.

PI(4)P has been observed on starvation-induced, non-selective autophagosomes (Miao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2015). To investigate if PI(4)P is present on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes and SCVs, we detected PI(4)P on LC3+ and LAMP1+ Salmonella in WT and SACM1L KO cells by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Loss of SAC1 increased the percentage of LC3+ autophagosomes associated with PI(4)P as well as PI(4)P fluorescence intensity (Figures 5C, 5D, and S5A). Although endogenous PI(4)P was detectable on less than 5% of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes in WT cells, the percentage doubled in SACM1L KO cells (Figure 5D). In contrast, we did not detect an increase in the percentage of LAMP1+ SCVs associated with PI(4)P or in PI(4)P fluorescence intensity on SCVs (Figures 5C, 5E, and S5A).

To better understand how PI(4)P is regulated by SAC1 during infection, we tracked its dynamics by live cell imaging using a PI(4)P-specific probe called BFP-2xP4M. The percentage of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes with detectable PI(4)P levels (i.e., GFP-LC3+BFP-2xP4M+ Salmonella) in SACM1L KO cells was initially similar to WT cells, which remained below 5% but reached a maximum of 12% by 150 min post-infection (Figures 5F and 5G), demonstrating that PI(4)P accumulates on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes upon SAC1 loss.

To test whether excessive PI(4)P on autophagosomal membranes impairs xenophagy in SAC1-deficient cells, we assessed the combined effect of PI4K knockdown in SACM1L KO cells on bacterial targeting and replication. Of the four human PI4Ks, only knockdown of PI4K2ɑ reduced Salmonella replication in WT cells (Figure 1A; Table S1). Similarly, we found that only knockdown of PI4K2ɑ ameliorated the defect in bacterial restriction in SACM1L KO cells (Figures 5H and S5B–S5D). The percentage of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes with PI(4)P was also reduced in both WT and SACM1L KO cells after PI4K2ɑ knockdown (Figure 5I). Furthermore, treatment with the PI4K2ɑ-specific inhibitor PI-273 (Li et al., 2017) suppressed accumulation of LC3 and ubiquitin, which serve as markers for autophagosomal maturation, on Salmonella in SACM1L KO cells at 2 h post-infection (Figures 5J and 5K). These results indicate that regulation of PI(4)P levels on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes by PI4K2ɑ and SAC1 is critical for efficient xenophagy.

SteA, a Salmonella effector protein, prevents maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes in a PI(4)P-dependent manner

Given that our data support a specific role for SAC1 in xenophagy, we reasoned that Salmonella PI(4)P-binding proteins may contribute to the replicative advantages observed in SACM1L KO cells. SteA is a Salmonella type III secreted effector protein that specifically binds to PI(4)P, but its role in xenophagy is unclear (Domingues et al., 2016). By using a CFU assay, we found that replication of ΔsteA Salmonella, unlike WT Salmonella, was restricted in SAC1-deficient cells (Figure 6A). Similar to WT Salmonella, however, ΔsteA Salmonella replication increased in cells lacking NDP52 (Figure 6A). Loss of neither SAC1 nor SteA had detectable effects on Salmonella uptake as determined by CFU assay 1 h post-infection (Figure S6A). Importantly, reconstituting the ΔsteA mutant with WT SteA, driven by its endogenous promoter or the stronger rpsM promoter, restored the Salmonella replicative advantage in SACM1L KO cells as compared to WT cells, whereas replication in NDP52 KO cells remained unchanged (Figures 6B and 6C).

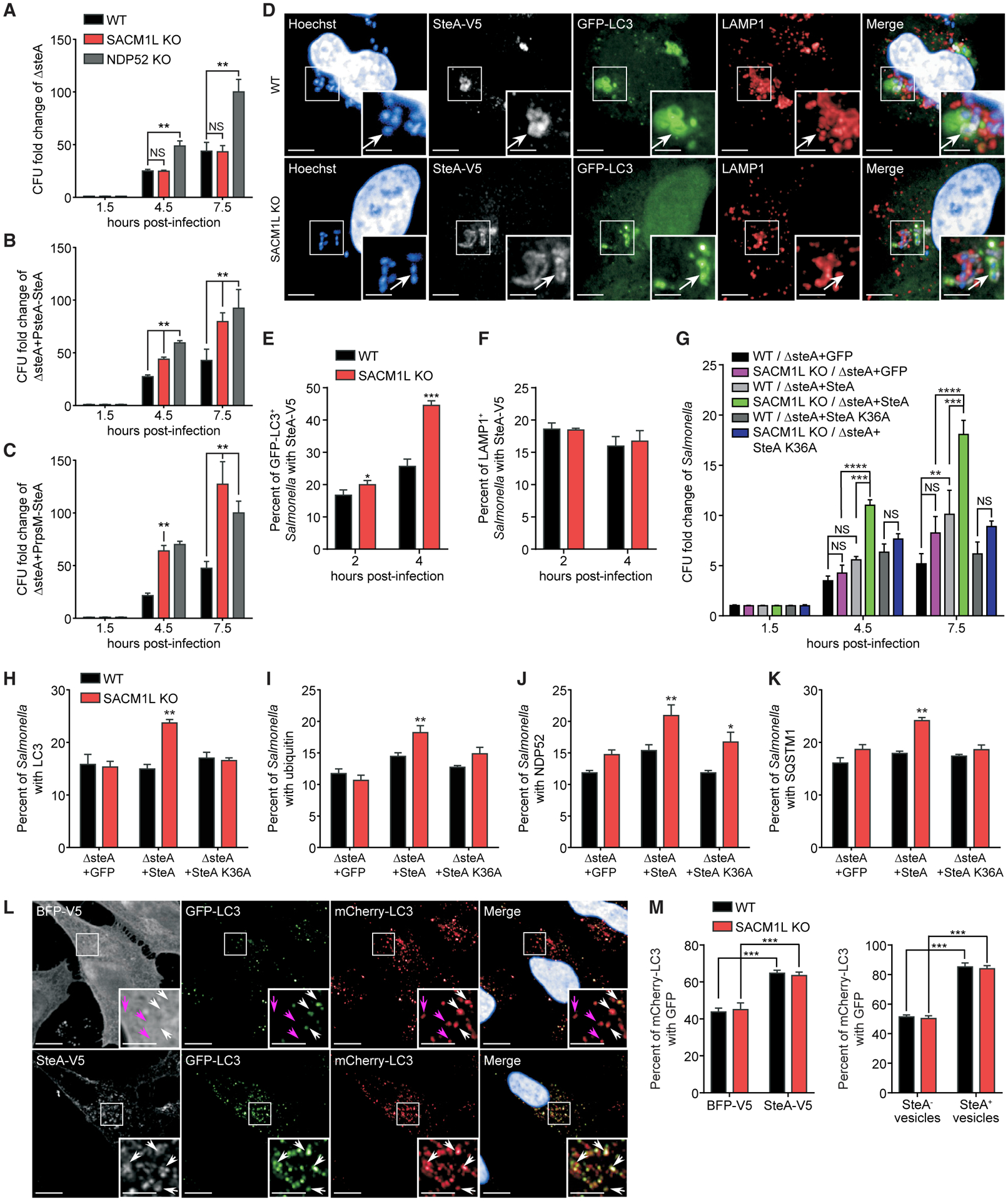

Figure 6. SteA, a Salmonella effector protein, prevents maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes in a PI(4)P-dependent manner.

(A–C) CFU fold change for the ΔsteA mutant (A) and ΔsteA mutant reconstituted with PsteA-SteA (B) or PrpsM-SteA (C) at indicated times post-infection of WT and SACM1L KO cells normalized to the 1.5-h time point.

(D) Representative confocal images of Salmonella associated with SteA-V5 (white arrows) in WT and SACM1L KO cells at 2 h post-infection with ΔsteA reconstituted with SteA-V5. Insets are boxed regions magnified (2×). Scale bars represent 10 μm in full images and 5 μm in insets.

(E and F) Percentage of LC3+ (E) or LAMP1+ (F) Salmonella associated with SteA-V5 at indicated times post-infection.

(G) CFU fold changes normalized to the 1.5-h time points for Salmonella strains at indicated times post-infection of WT and SACM1L KO cells.

(H–K) Percentage of LC3+ (H), ubiquitin+ (I), NDP52+ (J), or SQSTM1+ (K) Salmonella in WT and SACM1L KO cells at 2 h post-infection.

(L and M) Representative confocal images (L) and quantification (M) of mCherry-GFP-LC3 in WT and SACM1L KO cells transiently expressing BFP-V5 or SteA-V5 after 24 h. Hoechst shows nuclei. Scale bars represent 5 μm. Arrows indicate mCherry+GFP+ (white) and mCherry+GFP− (magenta) vesicles. For all quantifications, over 500 cells were analyzed. Three independent experiments were analyzed using ANOVA (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

See also Figure S6.

We next examined the subcellular localization of Salmonella-secreted SteA by infecting WT and SACM1L KO cells with a ΔsteA mutant expressing V5-tagged SteA. SteA-V5 co-localized with both LC3+ and LAMP1+ Salmonella-containing compartments, indicating that SteA interacts with autophagosomes and SCVs (Figure 6D) as previously reported (Domingues et al., 2014). SAC1 loss increased the percentage of SteA-V5+LC3+ Salmonella, providing evidence that SteA localization correlates with PI(4)P levels on autophagosomal membranes (Figure 6E). Meanwhile, the percentage of SteA-V5+LAMP1+ Salmonella was comparable in WT and SACM1L KO cells (Figure 6F), consistent with PI(4)P levels on LAMP1+ compartments (Figure 5E). Expression of SteA K36A-V5, which abolishes SteA binding to PI(4)P, dramatically decreased the recruitment of SteA to LC3+ Salmonella (Figures S6B and S6C). Reconstituting the ΔsteA mutant with WT SteA, but not SteA K36A or a GFP control, restored the replicative advantage of Salmonella in both SACM1L KO and WT cells, revealing the importance of SteA secretion to bacterial survival (Figure 6G). Unlike SACM1L KO cells, however, WT cells were able to suppress the replication of ΔsteA Salmonella, supporting the importance of host PI(4)P regulation in xenophagy (Figure 6G). Moreover, only ΔsteA Salmonella reconstituted with WT SteA induced LC3, ubiquitin, NDP52, and SQSTM1 accumulation in SACM1L KO cells and delayed maturation of autophagosomes (Figures 6H–6K and S6D), further indicating that SteA interferes with xenophagy in the presence of elevated PI(4)P levels.

To investigate how SteA impairs xenophagy, we transiently overexpressed SteA-V5 in mCherry-GFP-LC3 reporter cells. SteA-V5 co-localized with LC3 puncta and strongly impeded autophagosome acidification, as detected by increased levels of mCherry-LC3+ and GFP-LC3+ puncta in both WT and SACM1L KO cells compared with that of BFP-V5 control transfected cells (Figures 6L and 6M). These data indicate that SteA expression is sufficient to interfere with autophagosome-lysosomal fusion. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that SAC1 regulates the level of PI(4)P on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes, impairing the suppression of a host innate defense response by the Salmonella-secreted effector protein SteA.

DISCUSSION

Current models attribute specificity in selective autophagy to the binding of receptors to cargo, but a recent study revealed that NDP52 may also directly interact with lipid membranes during recruitment of autophagy initiation machinery (Shi et al., 2020). Moreover, the abundance of bacterial effectors that bind or modulate host phospholipids implicates their importance in host defense mechanisms (Haenssler and Isberg, 2011; Nachmias et al., 2019; Swart and Hilbi, 2020). Here, we investigated lipid membrane components as factors critical to xenophagy mechanisms.

From a targeted siRNA screen of lipid kinases and phosphatases, we identified the PI(4)P phosphatase SAC1 as a key regulator of intracellular bacterial replication. Both SACM1L knockdown and KO cells elevated bacterial replication. Re-expression of WT SAC1 restored bacterial replication restriction, whereas expression of the catalytically dead SAC1 C389S mutant did not, indicating that PI(4)P phosphatase activity is required for host defense. Our study found that SAC1 loss had no detectable effect on non-selective autophagy, Parkin-dependent mitophagy, or aggrephagy, revealing a specific influence of PI(4)P regulation on xenophagy. Two recent siRNA studies reported contradictory roles for SAC1 in non-selective autophagosome maturation; however, in these studies, SAC1 protein levels and genetic rescue experiments were not performed to evaluate siRNA efficiency and off-target effects (Miao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Our stable KO cells may also have compensated for the loss of SAC1 by using other phosphatases with less efficient activity on PI(4)P for constitutive autophagy functions.

As we did not detect defects in recognition or targeting of intracellular bacteria, we concluded that interactions between cargo receptors and membrane lipids were not responsible for the observed xenophagy defect. However, we found that SAC1 loss delayed accumulation of lysosomal markers on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes, indicating the importance of PI(4)P levels to autolysosomal maturation. Localization and activity of phosphoinositide lipids, regulators, and binding proteins collectively function to control subcellular membrane trafficking and interactions (Burke, 2018; Jeschke and Haas, 2018; Nishimura and Tooze, 2020). SAC1 is localized predominantly to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Liu et al., 2009; Zewe et al., 2018). A recent study demonstrated that TMEM39A/SUSR2 regulates SAC1 trafficking between the ER and Golgi and the loss of SAC1 increases cellular PI(4)P (Miao et al., 2020), which is predominantly found on the plasma membrane, Golgi, and endosomal compartments (D’Angelo et al., 2008; Zewe et al., 2020).

We similarly found that cells lacking SAC1 expression had increased levels of cellular PI(4)P that co-localized with Salmonella-containing autophagosomes and had no detectable effect on PI(4)P associated with SCVs. This finding suggests that, in contrast to SCVs, Salmonella-containing autophagosomes sequester or stabilize PI(4)P (Domingues et al., 2016; Santos et al., 2015). Furthermore, reducing PI(4)P levels in SACM1L KO cells by either a PI4K2ɑ siRNA or pharmacological inhibitor promoted maturation of Salmonella-containing autophagosomes and restricted bacterial replication. These results substantiate a role for SAC1-dependent regulation of PI(4)P in host defense.

Previous reports implicated PI4K2ɑ regulation of PI(4)P in non-selective autophagosome maturation (Albanesi et al., 2015; Baba et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2015), whereas our results indicate that SAC1 phosphatase activity is necessary to modulate PI(4)P levels on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes for efficient autolysosomal fusion. Collectively, these findings indicate that both increased and decreased PI(4)P levels on autophagosomal membranes impair fusion with lysosomes.

Considering that our results suggested a xenophagy-specific role for SAC1, we investigated the contribution of Salmonella to delaying lysosomal fusion as a result of PI(4)P accumulation on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes. We evaluated SteA, a Salmonella-secreted effector that binds specifically to PI(4)P and localizes to PI(4)P-rich SCVs when ectopically expressed in infected cells (Domingues et al., 2016; Matsuda et al., 2019). Importantly, both WT and SACM1L KO cells were able to restrict replication of Salmonella lacking SteA to different extents, supporting a role for SteA in replication. Meanwhile, SACM1L KO cells infected with Salmonella expressing SteA displayed increased bacterial replication and delayed degradation of autophagy markers on bacteria. We propose that the loss of SAC1 increases PI(4)P levels on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes, thereby promoting SteA accumulation, which impairs lysosomal fusion and results in increased bacterial replication. Based on our data, higher levels of SteA expression driven by a strong bacterial promoter increased bacterial numbers compared with endogenous SteA expression, further supporting that SteA accumulation on autophagosomal membranes facilitates Salmonella replication. Moreover, ectopic expression of SteA in either WT or SACM1L KO cells localized to autophagosomes and blocked basal autophagic flux, confirming that SteA plays a direct role in preventing lysosomal fusion.

Using live cell imaging, we observed an increase in Salmonella bacteria replicating in the cytosol of cells lacking SAC1 despite being targeted by autophagy machinery shortly after infection. These bacteria may account for the robust replication phenotype as compared to the modest autophagolysosome maturation phenotype. Recently, the lipid transporter and PI(4)P-binding protein OSBP1 was found to interact with SCVs through Salmonella effectors SseJ and SseL. Together, these proteins stabilize the SCV, and the loss of either the effectors or OSBP1 increases cytosolic bacteria (Kolodziejek et al., 2019). Dysregulation of PI(4)P may alter SCV stability in cells lacking SAC1, which may also contribute to the increase in bacterial replication; however, we did not observe a significant change in SCV integrity upon SAC1 loss.

Intracellular bacteria are known to manipulate host cell processes to develop replication-competent niches or avoid defense mechanisms (Asrat et al., 2014; Case and Samuel, 2016; Kimmey and Stallings, 2016; Pao and Rape, 2019). Salmonella, as well as other pathogens, produces an array of effector proteins—with functions ranging from inducing uptake to developing a replication-competent vacuole (Cardenal-Muñoz and Ramos-Morales, 2011)—that act both redundantly and cooperatively to ensure survival (Azimi et al., 2020; Ghosh and O’Connor, 2017). Our results highlight the importance of innate host defense to restrict bacterial replication and the role of bacterial factors in intracellular survival. In WT cells, SteA had a modest effect on bacterial survival; however, PI(4)P dysregulation shifted the advantage to Salmonella. Recent reports described the role of SopF, another phosphoinositide-binding effector, in promoting SCV membrane integrity as well as potently blocking xenophagy by modifying ATP6V0C, a vacuolar ATPase on the SCV, to prevent recruitment of the core autophagy protein ATG16L1 (Fischer et al., 2020; Lau et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019). Our data not only establish the importance of SAC1-dependent PI(4)P regulation in xenophagy-specific autophagolysosome maturation but also expand our understanding of how Salmonella SteA PI(4)P binding supports intracellular replication by interfering with a host defense mechanism.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ramnik J. Xavier (xavier@molbio.mgh.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

Materials generated in this study will be provided upon request.

Data and code availability

The published article contains all datasets generated during this study.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell line culture and small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown

HeLa and HEK293 cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma Aldrich), 100U/ml penicillin and 100mg/ml streptomycin. Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. siRNA knockdowns were achieved by transfection with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX according to the manufacturer’s instructions using Silencer Select siRNAs at 2nM (Table S2). For the siRNA knockdown screen of lipid kinase and phosphatase genes, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs at 2nM for 24h, followed by a media change and cultured for another 36h prior to infection with S. Typhimurium SL1344 expressing luciferase.

All the stable cell lines were generated with lentiviral transduction followed by either antibiotic selection or flow cytometry sorting based on the fluorescent tags.

Vector construction

All the plasmids in this study were generated by PCR and Gibson cloning using standard protocols with Gibson Assembly Master Mix.

Bacterial strains

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 and 14028s were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid media or on LB agar plates. S. Typhimurium ΔsteA deletion in 14028s strain was a gift from Dr. Luís Jaime Mota (Domingues et al., 2014). Reconstituted strains were generated using standard transformation procedures (Figueira et al., 2013) and grown at 37°C on LB plates containing the appropriate antibiotic for selection.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of CRISPR knockout cells

The Cas9 vector (pXPR_BRD023, Broad Institute) containing a SACM1L-specific single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence was used to transfect HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Media was replaced 24h post-transfection with selection media containing puromycin (2μg/ml). After 48h selection, surviving cells were plated in 96-well plates at 0.5 cells/well to isolate single clones. SACM1L knockout was confirmed by western blot and next generation sequencing. Guide RNA sequences:

SACM1L sg1: ACUGGGCACAAUCCAUCUGG

SACM1L sg2: UGGCUGUAAAAUACCUGCAA

Bacterial infection assays

Intracellular bacterial replication of S. Typhimurium SL1344 or SL1344 expressing bacterial luciferase was measured by a colony-forming unit (CFU) or luciferase assay, respectively. In general, S. Typhimurium strains SL1344 or 14028s were grown overnight from a single colony then subcultured for 3h at 37°C until late log phase. Subcultures were diluted in complete DMEM media containing 10% FBS to achieve multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1. Cells were infected with bacteria for 30min at 37°C, rinsed twice then incubated with complete DMEM media supplemented with 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Thermo Fisher) for 1h to kill extracellular bacteria. Cells were then rinsed twice and cultured with complete DMEM media containing 20μg/ml gentamicin. For luciferase assays, the first luciferase reading was taken at 1.5h post-infection and then every hour until 9.5h post-infection. For CFU assays, HeLa cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 at room temperature (RT) for 10min at indicated time points and intracellular Salmonella were serially diluted, plated on LB plates and colonies were counted following overnight incubation at 30°C. For both assays, the fold change was determined relative to the initial measured value at 1.5h post-infection.

For indicated imaging experiments, bacteria were labeled with CellTracker Deep Red Dye. Bacterial subcultures were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 5 μM CellTracker Deep Red Dye for 30min at 37°C with gentle agitation. Excessive dye was quenched by washing with Super Optimal Broth (SOB) media twice. Bacteria were recovered in SOB media for 30min at 37°C with gentle agitation. After the final wash with SOB media, the bacteria were used for infection as above.

Chloroquine (CHQ) resistance assay

CHQ resistance assay was performed as described previously (Knodler et al., 2014). HeLa cells were infected as in the CFU assay described above. One hour prior to the 1.5- and 7.5-hour time points, cells were treated with CHQ (200 μM) and gentamicin (50 μg/ml for the 1.5-hour time point; 20 μg/ml for 7.5-hour time point) for 1h. Control cells not treated with CHQ were incubated with gentamicin only. At each time point post-infection, cytosolic replication of Salmonella was evaluated as described above in the bacterial CFU assay.

X-light-mCherry bacterial assay

Cells were infected with bacteria expressing an IPTG-inducible fluorescent protein (x-light-mCherry) as an indicator of metabolic activity at the time of IPTG addition (Krokowski et al., 2018). For each time point, prior to fixation, the cells were treated with 1.5mM IPTG for 45min in complete DMEM media at 37°C, then fixed and stained for imaging.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded and grown on sterile glass coverslips or in a 96-well plate. Following treatments, cells were fixed and permeabilized with either ice cold 100% methanol for 3min or with PBS containing 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20min followed by PBS containing 0.2% (w/v) saponin for 8min. After extensive washing with PBS, coverslips were incubated in blocking buffer [PBS containing 5% (v/v) normal goat serum and 0.05% (w/v) saponin] for 1h at RT and then incubated with primary antibodies in the same buffer at 4°C overnight. Cells were washed with PBS then incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies in blocking buffer for 1h at RT. After washing with PBS, cells were sealed with Vectashield mounting medium for confocal microscopy analysis as described below.

Immunostaining of endogenous phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate [PI(4)P] was performed as previously described (Hammond et al., 2009) with the following modifications. Briefly, cells were fixed for 15min with 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (PB) containing 2% (v/v) PFA then washed three times with PBS containing 50mM NH4Cl. Cells were permeabilized for 5min with 20 μM digitonin in buffer A [20mM PIPES (pH 6.8) containing 137mM NaCl and 2.7mM KCl] then blocked for 1h with blocking buffer (Buffer A containing 5% normal goat serum and 50mM NH4Cl). Cells were incubated with an anti-PI(4)P primary antibody diluted 1:200 in buffer A for 1h at RT or 4°C overnight. After two washes with buffer A, secondary antibodies were added for 45min in the blocking buffer. Cells were washed and post-fixed for 5min with PBS containing 2% (v/v) PFA. Fixative was removed by washing three times with PBS containing 50mM NH4Cl then subjected to imaging.

Staining of BODIPY FL-pepstatin A was performed after secondary antibodies. Cells were washed twice with 300mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) with 0.1% Brij 35, then incubated in the same buffer containing 1uM BODIPY FL-pepstatin A at RT for 1h. Cells were washed again with sodium acetate buffer before imaging.

BFP-2xP4M and GFP-LC3 were stably expressed by lentiviral transduction. After 7d, cells were infected with DsRed-expressing Salmonella, washed and imaged by live confocal microscopy at 2h post-infection.

Microscopy

For fixed cells, fluorescence images were obtained with a Perkin Elmer Opera Phenix system using a 60× 1.42 N.A. water objective or with a Nikon Ti2-E inverted microscope equipped with a CSU-W1 spinning disc confocal and Andor Zyla 4.2 sCMOS camera using a 100× 1.40 N.A. oil objective. To record the dynamics of xenophagy in HeLa cells, images were obtained with the Perkin Elmer Opera Phenix system using a 60× 1.42 N.A. water objective. Cells were plated in CellCarrier-96 Ultra Microplates in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS then treated and infected as indicated. During imaging, the plates or dishes were placed in a humidified chamber supplemented with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Images were captured every 15 or 30min with a Z stack of 1 μm/section for a total of three sections. After acquisition, the images were projected to form one image by maximum-intensity projection. Analysis of images was performed using Harmony High-Content Imaging and Analysis Software or Columbus Image Data Storage and Analysis System. To quantify association of markers with intracellular bacteria, we defined the bacterial region using the micronuclei software setting, which was expanded by 2 pixels beyond the bacterial signal to detect overlapping signals in a defined and consistent manner. The mean and sum intensities as well as contrast of associated fluorescent signals within the bacterial region were calculated and used to define a threshold for each of the individual markers being evaluated. All parameters were unchanged when quantifying the percentage of association in WT and SACM1L KO cells.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Waltham, MA). cDNA was prepared using 0.5–1 μg total RNA by RT-PCR using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed on 5 μL cDNA using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and primers designed to recognize the indicated genes. Fold changes were calculated by the Delta-Delta-Ct method using human GAPDH as the control. All fold changes were expressed as normalized to the WT or untreated control.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For analysis of the siRNA screen, data was normalized to the SiSel_NC control siRNA on each plate and log2 transformed. For each gene, a linear mixed-effects model (lme function in nlme R package) was then used to test whether the log expression difference from SiSel_NC was nonzero, with the experiment as the random effect. P values were derived from F tests. Multiple hypothesis correction was done using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate.

Statistical analyses were done using Prism (GraphPad Software) or Excel (Microsoft Office) to generate curves or bar graphs. All error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-tailed unpaired t tests were used for statistical analysis of two groups of samples. One-way ANOVA analysis of variance with a Newman-Keuls post-test was used to evaluate statistical significance of multiple groups of samples. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. p ≥ 0.05 was considered not significant (NS).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-LC3 clone APG8C | Sigma-Aldrich | SAB1301850 |

| Rabbit anti-LC3B | Cell Signaling Technology | 3868 |

| Mouse anti-β-Actin | Sigma-Aldrich | A5441; RRID:AB_476744 |

| Rabbit anti-NDP52 | Abcam | ab68588; RRID:AB_1640255 |

| Mouse anti-p62 | Abcam | ab109012; RRID:AB_2810880 |

| Mouse anti-V5 | Abcam | ab27671; RRID:AB_471093 |

| FK2 anti-ubiquitin | Enzo Life Sciences | BML-PW8810; RRID:AB_10541840 |

| Rabbit anti-SACM1L | Abnova | H00022908-D01P; RRID:AB_10632266 |

| Rabbit anti-SACM1L | Thermo Fisher | 13033-1-AP; RRID:AB_2301284 |

| Mouse anti-TOMM20 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-17764; RRID:AB_628381 |

| Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies | Thermo Fisher | A31571; RRID:AB_162542, A21206; RRID:AB_2535792, A32744; RRID:AB_2762826 |

| Sheep anti-TGN46 | Bio-Rad | AHP500; RRID:AB_324049 |

| Mouse anti-GM130 | BD | 610822; RRID:AB_398141 |

| Mouse anti-WIPI2 | Abcam | ab105459; RRID:AB_10860881 |

| Mouse anti-PtdIns(4)P IgM | Echelon | Z-P004–2 |

| Rabbit anti-LAMP1 | Cell Signaling Technology | 9091; RRID:AB_2687579 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| S. Typhimurium SL1344 | Hoiseth and Stocker, 1981 | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL1344 Xen26 | Conway et al., 2013 | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL1344 DsRed | Rioux et al., 2007 | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL14028s ΔsteA | Laboratory of Dr. Luís Jaime Mota | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL14028s ΔsteA reconstituted with PsteA-SteA | This study | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL14028s ΔsteA reconstituted with PrpsM-SteA | This study | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL14028s ΔsteA reconstituted with PsteA-SteA K36A | This study | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL14028s ΔsteA reconstituted with PsteA-SteA-V5 | This study | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL1344 x-light-mCherry | This study | N/A |

| S. Typhimurium SL1344 mCerulean | This study | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Torin1 | MedChemExpress | Hy-13003 |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Selleckchem | S1413 |

| Hoechst 33342 | Thermo Fisher | H3570 |

| Puromycin | InvivoGen | ant-pr-1 |

| Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside | Sigma-Aldrich | 367-93-1 |

| Chloroquine | Sigma-Aldrich | C6628 |

| Carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) | Sigma-Aldrich | C2759 |

| Oligomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | 75351 |

| Antimycin A | Sigma-Aldrich | A8674 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Thermo Fisher | 11668027 |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX | Thermo Fisher | 13778150 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 15714S |

| VectaShield | Vector Laboratories | H-1000-10 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| LysoTracker Red DND-99 | Thermo Fisher | L7528 |

| DQ Green BSA | Thermo Fisher | D12050 |

| Ovalbumin AF647 | Thermo Fisher | O34784 |

| CellTracker Deep Red Dye | Thermo Fisher | C34565 |

| BODIPY FL-pepstatin A | Thermo Fisher | P12271 |

| Magic Red Cathepsin B | ImmunoChemistry Technologies | 938 |

| LysoView 633 | Biotium | 70058 |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | New England Biolabs | E2611 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human: HeLa | ATCC | Cat #CCL-2; RRID:CVCL_0030 |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO reconstituted with BFP-V5 | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO reconstituted with SACM1L-V5 WT | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO reconstituted with SACM1L-V5 C389S | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa NDP52 KO | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa mCherry-GFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa GFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa GFP-LC3; LAMP1-mCherry | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa GFPLC3; BFP-2xP4M | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO mCherry-GFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO GFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO GFP-LC3; LAMP1-mCherry | This paper | N/A |

| Human: HeLa SACM1L KO GFP-LC3; BFP-2xP4M | This paper | N/A |

| Human: H4 | ATCC | Cat#HTB-148; RRID:CVCL_1239 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Silencer Select siRNA | Thermo Fisher | See Table S2 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| CGSW-mCherry-GFP-LC3 | Laboratory of Dr. Christian Münz | N/A |

| CSGW-GFP-LC3 | Laboratory of Dr. Christian Münz | N/A |

| pKB269 IPTG inducible x-light-mCherry | Laboratory of Dr. Serge Mostowy | Sirianni et al., 2016 |

| pBMN-mCherry-Parkin | Addgene | (Yamano et al., 2014); RRID:Addgene_59419 |

| pEGFP-hGal3 | Addgene | Maejima et al., 2013; RRID:Addgene_73080 |

| LAMP1-mRFP-FLAG | Addgene | (Zoncu et al., 2011); RRID:Addgene_34611 |

| pFPV25.1 | Addgene | Valdivia and Falkow, 1996 |

| pFPV25.1_rpsM_mCerulean3 | Addgene | Lane et al., 2019; RRID:Addgene_124904 |

| pXPR-BRD023 | Broad Institute | N/A |

| pXPR-BRD003 | Broad Institute | N/A |

| pLX317-BFP | Broad Institute | N/A |

| pLX317-SACM1L-V5 | This paper | N/A |

| pLX317-SACM1L(C389S)-V5 | This paper | N/A |

| pSFFV-P4M(SidM)x2-BFP | This paper | N/A |

| pFPV25.1-PrpsM-SteA | This paper | N/A |

| pFPV25.1-PSteA-SteA | This paper | N/A |

| pFPV25.1-PsteA-SteA(K36A) | This paper | N/A |

| pFPV25.1-PSteA-SteA-V5 | This paper | N/A |

| pFPV25.1-PsteA-SteA(K36A)-V5 | This paper | N/A |

| pLX304-EF1a-SteA-V5 | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| NIS-Elements | Nikon | N/A |

| Harmony High-Content Imaging and Analysis Software | Perkin Elmer | N/A |

| GraphPad Prism8 | GraphPad Software, Inc. | N/A |

| Flowjo | FLOWJO | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

Highlights.

Phosphoinositide kinase and phosphatase screen reveals SAC1 as a xenophagy regulator

SAC1 deficiency impairs fusion of bacteria-containing autophagosomes with lysosomes

Loss of SAC1 leads to PI(4)P accumulation on Salmonella-containing autophagosomes

The Salmonella effector protein SteA binds excess PI(4)P, impeding lysosomal fusion

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Luís Jaime Mota at NOVA University of Lisbon for the generous gift of S. Typhimurium ΔsteA deletion, Tamotsu Yoshimori at Osaka University for the pEGFP-hGal3 plasmid, Serge Mostowy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for the pKB269 x-light mCherry plasmid, Leigh Baxt for generation of x-light mCherry-expressing Salmonella, Herbert (Skip) Virgin and the late Beth Levine for invaluable feedback, Theresa Reimels for help with manuscript preparation, and Jacques Deguine for comments. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (U19AI109725, U19AI142784, R01DK117263, and R01DK097485 to R.J.X.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109434.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

R.J.X. is co-founder of Jnana Therapeutics and Celsius Therapeutics. These organizations had no roles in this study.

REFERENCES

- Albanesi J, Wang H, Sun HQ, Levine B, and Yin H (2015). GABARAP-mediated targeting of PI4K2A/PI4KIIα to autophagosomes regulates PtdIns4P-dependent autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 11, 2127–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrat S, de Jesús DA, Hempstead AD, Ramabhadran V, and Isberg RR (2014). Bacterial pathogen manipulation of host membrane trafficking. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 30, 79–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi T, Zamirnasta M, Sani MA, Soltan Dallal MM, and Nasser A (2020). Molecular Mechanisms of Salmonella Effector Proteins: A Comprehensive Review. Infect. Drug Resist 13, 11–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Toth DJ, Sengupta N, Kim YJ, and Balla T (2019). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate controls Rab7 and PLEKHM1 membrane cycling during autophagosome-lysosome fusion. EMBO J. 38, e100312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett TC, Liebl D, Seymour LM, Gillen CM, Lim JY, Larock CN, Davies MR, Schulz BL, Nizet V, Teasdale RD, and Walker MJ (2013). The globally disseminated M1T1 clone of group A Streptococcus evades autophagy for intracellular replication. Cell Host Microbe 14, 675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin JL, Sumpter R Jr., Levine B, and Hooper LV (2013). Intestinal epithelial autophagy is essential for host defense against invasive bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 13, 723–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bento CF, Renna M, Ghislat G, Puri C, Ashkenazi A, Vicinanza M, Menzies FM, and Rubinsztein DC (2016). Mammalian Autophagy: How Does It Work? Annu. Rev. Biochem 85, 685–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham CL, Smith AC, Bakowski MA, Yoshimori T, and Brumell JH (2006). Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J. Biol. Chem 281, 11374–11383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, and Johansen T (2005). p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J. Cell Biol 171, 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JE (2018). Structural Basis for Regulation of Phosphoinositide Kinases and Their Involvement in Human Disease. Mol. Cell 71, 653–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenal-Muñoz E, and Ramos-Morales F (2011). Analysis of the expression, secretion and translocation of the Salmonella enterica type III secretion system effector SteA. PLoS One 6, e26930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case EDR, and Samuel JE (2016). Contrasting Lifestyles Within the Host Cell. Microbiol. Spectr 4, 0014–2015. 10.1128/microbiol-spec.VMBF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanheira S, and García-Del Portillo F (2017). Salmonella Populations inside Host Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 7, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, and Chen ZJ (2018). PtdIns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 564, 71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CS, Chen WN, Zhou M, Arttamangkul S, and Haugland RP (2000). Probing the cathepsin D using a BODIPY FL-pepstatin A: applications in fluorescence polarization and microscopy. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 42, 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sun HQ, Eichorst JP, Albanesi JP, Yin H, and Mueller JD (2018). Comobility of GABARAP and Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase 2A on Cytoplasmic Vesicles. Biochemistry 57, 3556–3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy A, Dancourt J, Mugo B, O’Connor TJ, Isberg RR, Melia TJ, and Roy CR (2012). The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science 338, 1072–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AJ, and Simon AK (2019). Autophagy in the renewal, differentiation and homeostasis of immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol 19, 170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EL, Minogue S, and Waugh MG (2013). Mammalian phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases as modulators of membrane trafficking and lipid signaling networks. Prog. Lipid Res 52, 294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KL, Kuballa P, Song JH, Patel KK, Castoreno AB, Yilmaz OH, Jijon HB, Zhang M, Aldrich LN, Villablanca EJ, et al. (2013). Atg16l1 is required for autophagy in intestinal epithelial cells and protection of mice from Salmonella infection. Gastroenterology 145, 1347–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo G, Vicinanza M, Di Campli A, and De Matteis MA (2008). The multiple roles of PtdIns(4)P—not just the precursor of PtdIns(4,5)P2. J. Cell Sci 121, 1955–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Armi C, Devereaux KA, and Di Paolo G (2013). The role of lipids in the control of autophagy. Curr. Biol 23, R33–R45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Ballina LR, Munson MJ, and Simonsen A (2020). Lipids and Lipid-Binding Proteins in Selective Autophagy. J. Mol. Biol 432, 135–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tito S, Hervás JH, van Vliet AR, and Tooze SA (2020). The Golgi as an Assembly Line to the Autophagosome. Trends Biochem. Sci 45, 484–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bel LM, and Brill JA (2018). Sac1, a lipid phosphatase at the interface of vesicular and nonvesicular transport. Traffic 19, 301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deosaran E, Larsen KB, Hua R, Sargent G, Wang Y, Kim S, Lamark T, Jauregui M, Law K, Lippincott-Schwartz J, et al. (2013). NBR1 acts as an autophagy receptor for peroxisomes. J. Cell Sci 126, 939–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson EJ, and Hille B (2019). Understanding phosphoinositides: rare, dynamic, and essential membrane phospholipids. Biochem. J 476, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues L, Holden DW, and Mota LJ (2014). The Salmonella effector SteA contributes to the control of membrane dynamics of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. Infect. Immun 82, 2923–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues L, Ismail A, Charro N, Rodríguez-Escudero I, Holden DW, Molina M, Cid VJ, and Mota LJ (2016). The Salmonella effector SteA binds phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate for subcellular targeting within host cells. Cell. Microbiol 18, 949–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley HC, Razi M, Polson HE, Girardin SE, Wilson MI, and Tooze SA (2014). WIPI2 links LC3 conjugation with PI3P, autophagosome formation, and pathogen clearance by recruiting Atg12-5-16L1. Mol. Cell 55, 238–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueira R, Watson KG, Holden DW, and Helaine S (2013). Identification of salmonella pathogenicity island-2 type III secretion system effectors involved in intramacrophage replication of S. enterica serovar typhimurium: implications for rational vaccine design. mBio 4, e00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer TD, Wang C, Padman BS, Lazarou M, and Youle RJ (2020). STING induces LC3B lipidation onto single-membrane vesicles via the V-ATPase and ATG16L1-WD40 domain. J. Cell Biol 219, e202009128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fracchiolla D, Chang C, Hurley JH, and Martens S (2020). A PI3K-WIPI2 positive feedback loop allosterically activates LC3 lipidation in autophagy. J. Cell Biol 219, e201912098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatica D, Lahiri V, and Klionsky DJ (2018). Cargo recognition and degradation by selective autophagy. Nat. Cell Biol 20, 233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, and O’Connor TJ (2017). Beyond Paralogs: The Multiple Layers of Redundancy in Bacterial Pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 7, 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Valero L, Rusniok C, Carson D, Mondino S, Pérez-Cobas AE, Rolando M, Pasricha S, Reuter S, Demirtas J, Crumbach J, et al. (2019). More than 18,000 effectors in the Legionella genus genome provide multiple, independent combinations for replication in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2265–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenssler E, and Isberg RR (2011). Control of host cell phosphorylation by legionella pneumophila. Front. Microbiol 2, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond GR, Schiavo G, and Irvine RF (2009). Immunocytochemical techniques reveal multiple, distinct cellular pools of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5) P(2). Biochem. J 422, 23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TE, and Johansen T (2011). Following autophagy step by step. BMC Biol. 9, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, Shirane M, and Nakayama KI (2018). TMEM55B contributes to lysosomal homeostasis and amino acid-induced mTORC1 activation. Genes Cells 23, 418–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RJ, Goel G, Baxt LA, Rush JS, Mohanan V, Paulus GLC, Jani V, Lassen KG, and Xavier RJ (2016). RNF166 Determines Recruitment of Adaptor Proteins during Antibacterial Autophagy. Cell Rep. 17, 2183–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo JM, Ordureau A, Paulo JA, Rinehart J, and Harper JW (2015). The PINK1-PARKIN Mitochondrial Ubiquitylation Pathway Drives a Program of OPTN/NDP52 Recruitment and TBK1 Activation to Promote Mitophagy. Mol. Cell 60, 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiseth SK, and Stocker BA (1981). Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291, 238–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horenkamp FA, Kauffman KJ, Kohler LJ, Sherwood RK, Krueger KP, Shteyn V, Roy CR, Melia TJ, and Reinisch KM (2015). The Legionella Anti-autophagy Effector RavZ Targets the Autophagosome via PI3P- and Curvature-Sensing Motifs. Dev. Cell 34, 569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, and Brumell JH (2014). Bacteria-autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 12, 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]