Abstract

Aims:

Bother attributed to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) drives care-seeking and treatment aggressiveness. The longitudinal relationship of LUTS severity and bother in a care-seeking cohort, however, is not well understood. We aim to conduct a longitudinal evaluation of LUTS severity and bother and identify characteristics of patients with discordant LUTS bother relative to severity.

Methods:

Men and women with LUTS seeking care at six US tertiary care centers enrolled in the symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network study. Patients reporting at least one urinary symptom based on the LUTS Tool were prospectively enrolled from June 2015 to January 2017. Correlations were used to assess the relationship between LUTS severity and bother. Discordance scores (ie, the difference between bother and severity) were used to classify patients with high and low bother. Patients were classified as having high or low bother phenotypes if scores were one standard deviation above or below zero, respectively. Repeated measures multinomial logistic regression evaluated characteristics associated with high and low bother phenotypes.

Results:

LUTS severity and bother were at least moderately correlated for all symptom items and highly correlated for 13 out of 21 items. Correlations were highest for urgency, and lowest for daytime frequency and urinary incontinence. Odds of being in high bother phenotype were lowest at 3 and 12 months (3 months vs baseline odds ratio [OR] = 0.71, 95% confidence ninterval [CI] = 0.54–0.94; 12 months vs baseline OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.48–0.91), and highest for those who endorsed all urgency questions (OR = 3.65, 95% CI = 2.17–6.13). Odds of being in the low bother phenotype were lowest for patients who endorsed all urgency items (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.26–0.42), and all frequency items (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.53–0.88).

Conclusions:

LUTS severity and bother correlate highly and measurement of both in clinical practice is likely redundant. There are patient factors associated with discordance which may justify additional evaluation.

Keywords: correlations, lower urinary tract symptoms

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are highly prevalent in men and women aged ≥40 years, affecting up to 72.3% of men and 76.3% of women, and prevalence increases with age.1,2 LUTS have been associated with a decline in health-related quality of life, general health status, and mental health.3 Though some may believe that the most severe symptoms would be the most bothersome, individuals may also be bothered by less severe symptoms. It is important to understand how the presence, frequency, and severity of a symptom interact with bother from that symptom over time in individuals, as these have all been shown to have some impact on treatment received.4–6

The degree of bother attributed to LUTS has been proposed as a primary driver of care-seeking and treatment aggressiveness.7 The degree to which bother and symptom severity interact, however, is not well understood. If, as is commonly believed, bother depends on symptom severity in a predictable way, that is, increases in symptom severity have associated increases in bother ratings, then symptom severity information is sufficient for the assessment of LUTS, thereby potentially negating the need for clinicians to evaluate both severity and bother of a given symptom. Existing data suggests that the overall severity of LUTS is highly correlated with LUTS bother2,6,8 supporting this hypothesis. However, if there is a threshold effect by which symptoms above a given severity level all produce the same level of bother, then both symptom severity and bother rating are needed to understand care-seeking behavior.

Previous investigations have evaluated reasons driving care-seeking among individuals with LUTS.4,5,7,9 In this study, we sought to expand on the bother component of care-seeking behavior and investigate the long-term stability of the relationship between symptom severity and bother by conducting a longitudinal evaluation of the correlation between severity and bother ratings in men and women seeking care for LUTS. In addition, we explored individual variation in the relationship between symptom severity and bother ratings and characteristics of individuals with discordant severity-bother phenotypes.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

The symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network (LURN) was established in 2012 with the goal of evaluating and addressing gaps in understanding and measuring LUTS, to ultimately improve the lives of those with lower urinary tract dysfunction. LURN is a multi-center National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases sponsored research network. The development of LURN, its objectives, and the conceptual framework has been described previously.10 The institutional review boards from all participating sites approved the study protocol for the LURN observational cohort study.

Patients seeking care for LUTS at six US tertiary care sites were recruited and prospectively enrolled in LURN Observational Cohort Study from June 2015 to January 2017. Patients were invited to participate if they reported at least one urinary symptom on the LUTS Tool11 with a one-month recall period.

Both men and women at least 18 years old presenting for the first time to a LURN physician or for a return visit (men only) were recruited, including those that may have received prior treatment for their LUTS. Detailed information about the study protocol and data collection has been previously reported, including considerations for statistical power.12 Based on the prospective sample size, the statistical power of the study was greater than 90% for detecting correlations as small as 0.15 and odds ratio (OR) as small as 1.3 for outcome prevalence of 30%.

2.2 |. Measures

All measures were collected at baseline, 3-month, and 12-month visits. The LUTS Tool includes an assessment of the severity and bother of 22 self-reported urinary symptoms using a one-week recall period. For all analyses, 21 of the 22 LUTS tool items were used. Urinary incontinence (UI) with sex was not included due to relatively higher levels of missingness and hypothesized informative missingness. Items were rated between zero and four, with higher ratings representing higher severity or bother. LUTS tool items were grouped into six symptom groups: frequency, urgency, incontinence, obstructive symptoms, pain, and post-micturition (Table S1). Patient reported outcome measurement information system (PROMIS) questionnaires of diarrhea, constipation, bowel incontinence, depression, and anxiety were administered.13,14 Scores for each measure were based on a T-Metric scaled to a reference population (mean = 50, SD = 10), with higher scores indicating higher degree of the subset being measured. The geniotourinary pain index (GUPI)15 evaluates pain symptoms associated with chronic pelvic pain, urinary symptoms, and quality of life. Scores range from zero to 45 with higher scores indicating more pain. The perceived stress scale16 (PSS) measures subjective stress. Individual scores range from zero to 40, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress.

2.3 |. Statistical analyses

For this study, we required that patients complete at least 15 of the 21 LUTS Tool severity questions at each timepoint. Missing data was minimal for the LUTS Tool among those that met this criteria (<2% overall). For timepoints with at least 50% non-missing expected bother responses (ie, responded 1 or higher for the severity item), missing bother responses were imputed. Otherwise, the timepoint was removed from the analysis. Multiple imputation using sequential regression techniques was performed in IVEWare Version 2.0.17,18

Polychoric correlations were calculated to estimate the correlation between LUTS tool severity and bother at the item level (by timepoint) and at the patient level. Patient level correlations were calculated for each patient with at least five items endorsed (i.e., item severity rating of one or higher). Correlations less than 0.3 were considered poor, 0.3 to 0.5 low, 0.5 to 0.7 moderate, and 0.7 or greater represented high correlations.19 To evaluate item level correlations over time and between men and women, 21 repeated measures linear regression models were fitted using item severity and bother standardized to zero mean and unit variance. In each model, bother was regressed on severity, sex, timepoint, and interactions between severity and sex and severity and timepoint.

Discordance scores were calculated by taking the difference between bother and severity for each item. Scores ranged from −4 (severe but not bothersome) to +4 (not severe but bothersome), with zero representing no discordance (i.e., equal severity and bother). The same calculation was completed for average severity and bother among all endorsed symptoms and within each of the six symptom categories. Patients were defined as being in the “high bother phenotype” or “low bother phenotype” if their average discordance was at least one standard deviation above or below zero, respectively. Patients not meeting either definition were considered to have “concordant bother.” Repeated measures multinomial logistic regression was performed to assess factors associated with being in the high and low bother phenotypes. Covariates considered for model selection included: age, sex, race, body mass index, major psychiatric disease, depression, functional comorbidity index, GUPI total score, PSS score, PROMIS T-scores, and indicators for endorsement of all items in each of the six symptom categories. Model selection was completed using the method of best subsets.20 All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Sample description

A total of 1040 LURN patients (508 men and 532 women) were included in the study for baseline evaluation. At 3 and 12 months, 887 patients (443 men and 444 women) and 832 patients (429 men and 403 women) met criteria for inclusion. Patients were on average 58.7 years old, white (84%), and overweight or obese (76%; Table 1). On average, men were older (61.2 vs 56.3; P < .001) and more likely to be overweight or obese (79% vs 73%; P = .011).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and medical history of LURN patients by sex

| N (%) or mean (SD) | Total (n = 1040) N (%) or mean (SD) | Male (n = 508) N (%) or mean (SD) | Female (n = 532) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.7 (14.2) | 61.2 (13.4) | 56.3 (14.6) | <.0001 |

| Race | .4541 | |||

| White | 849 (84%) | 413 (84%) | 436 (83%) | |

| Black | 113 (11%) | 49 (10%) | 64 (12%) | |

| Other | 53 (5%) | 28 (6%) | 25 (5%) | |

| BMI category | <.0001 | |||

| Underweight | 4 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Normal weight | 244 (24%) | 104 (21%) | 140 (27%) | |

| Overweight | 339 (33%) | 198 (39%) | 141 (27%) | |

| Obese | 441 (43%) | 202 (40%) | 239 (46%) | |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 371 (36%) | 147 (29%) | 224 (43%) | <.0001 |

| Depression | 291 (28%) | 115 (23%) | 176 (34%) | .0001 |

| FCI total score | 2.3 (2.0) | 2.2 (1.8) | 2.4 (2.2) | .4573 |

| GUPI total score | 14.5 (7.8) | 13.2 (7.6) | 15.9 (7.8) | <.0001 |

| GUPI pain subscale | 4.1 (4.6) | 3.7 (4.3) | 4.6 (4.8) | .0010 |

| GUPI urinary symptoms subscale | 4 (2.5) | 3.9 (2.4) | 4 (2.6) | .8524 |

| PSS total score | 12.0 (7.4) | 11.1 (7.2) | 12.8 (7.5) | .0004 |

| PROMIS anxiety T-score | 49.8 (9.1) | 48.6 (9.1) | 50.9 (9.0) | <.0001 |

| PROMIS depression T-score | 49.1 (8.8) | 48.2 (8.8) | 49.9 (8.8) | .0011 |

| PROMIS physical function T-score | 48.2 (9.9) | 49.6 (9.3) | 46.9 (10.4) | <.0001 |

| PROMIS sleep disturbance T-score | 52.5 (8.7) | 51.6 (8.6) | 53.3 (8.6) | .0032 |

| PROMIS GI bowel T-score | 5.3 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.2) | 5.6 (2.8) | .0778 |

| PROMIS GI constipation T-score | 50.1 (8.4) | 48.9 (7.9) | 51.3 (8.7) | <.0001 |

| PROMIS GI diarrhea T-score | 47.8 (8.8) | 46.7 (7.8) | 48.9 (9.6) | .0020 |

| Endorsed all LUTS tool post-micturition symptoms | 722 (69%) | 363 (71%) | 359 (67%) | .1642 |

| Endorsed all LUTS tool voiding symptoms | 253 (24%) | 155 (31%) | 98 (18%) | <.0001 |

| Endorsed all LUTS tool pain symptoms | 160 (15%) | 77 (15%) | 83 (16%) | .8427 |

| Endorsed all LUTS tool frequency symptoms | 834 (80%) | 418 (82%) | 416 (78%) | .0982 |

| Endorsed all LUTS tool urgency symptoms | 760 (73%) | 317 (62%) | 443 (83%) | <.0001 |

| Endorsed all LUTS tool incontinence symptoms | 145 (14%) | 22 (4%) | 123 (23%) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FCI, functional comorbidity index; GI, gastrointestinal; GUPI, genitourinary pain index; LURN, lower urinary tract dysfunction network; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PSS, perceived stress scale; PROMIS, patient reported outcome measurement information system.

P value for male versus female from the χ2 test or Wilcoxon 2-sample test.

3.2 |. Correlations and differences between severity and bother

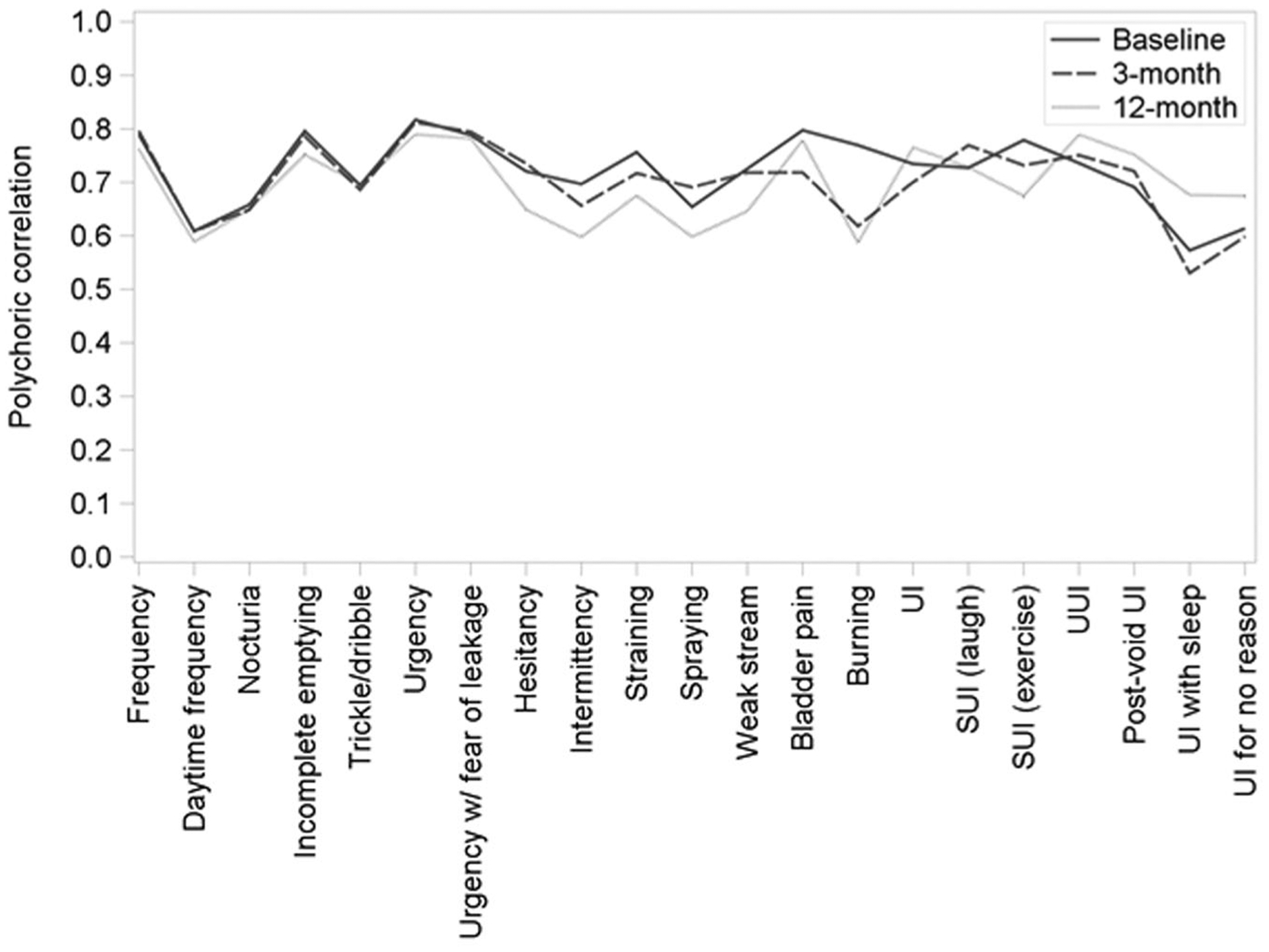

At baseline, correlations between severity and bother by item ranged from 0.57 (UI with sleep) to 0.82 (urgency). Correlations were generally consistent over time, with no evidence of statistically significant pairwise differences between the three timepoints. Correlations were at least moderate (≥0.5) at two or more timepoints for all 21 items and high (≥0.7) at two or more timepoints for 13 of 21 items (Figure 1). The LUTS Tool item with the highest correlations between severity and bother was urgency, ranging from 0.79 to 0.82 across the three timepoints, while daytime frequency (range 0.59 to 0.61), UI while sleeping (range 0.53 to 0.68) and UI for no reason (range 0.60 to 0.67) had the lowest correlations (Table S2).

FIGURE 1.

Polychoric correlation coefficients for lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS) tool severity and bother items (imputed data, by timepoint). Line graph of polychoric correlation coefficients for LUTS tool severity and bother items. Each value on the x-axis represents a different LUTS tool question, polychoric correlation values are shown on the y-axis, and each line represents one of the three timepoints (baseline, 3 months, and 12 months). SUI, stress urinary ncontinence; UI, urinary incontinence

Correlations between severity and bother in men and women were largely similar at baseline, with the exception of significantly higher correlations in women for frequency (0.81 vs 0.77) and straining (0.79 vs 0.73), and significantly higher correlations in men for nocturia (0.68 vs 0.67) and hesitancy (0.75 vs 0.66) (Table S3). All correlation differences between men and women were less than 0.1.

Correlations were mostly strongly positive (median ≥0.75 for all three timepoints) (Figure S1). Patient-level correlations spanned the full range (−1 to 1), with 5% of patients having negative correlations between severity and bother at baseline, 7% at 3 months, and 5% at 12 months.

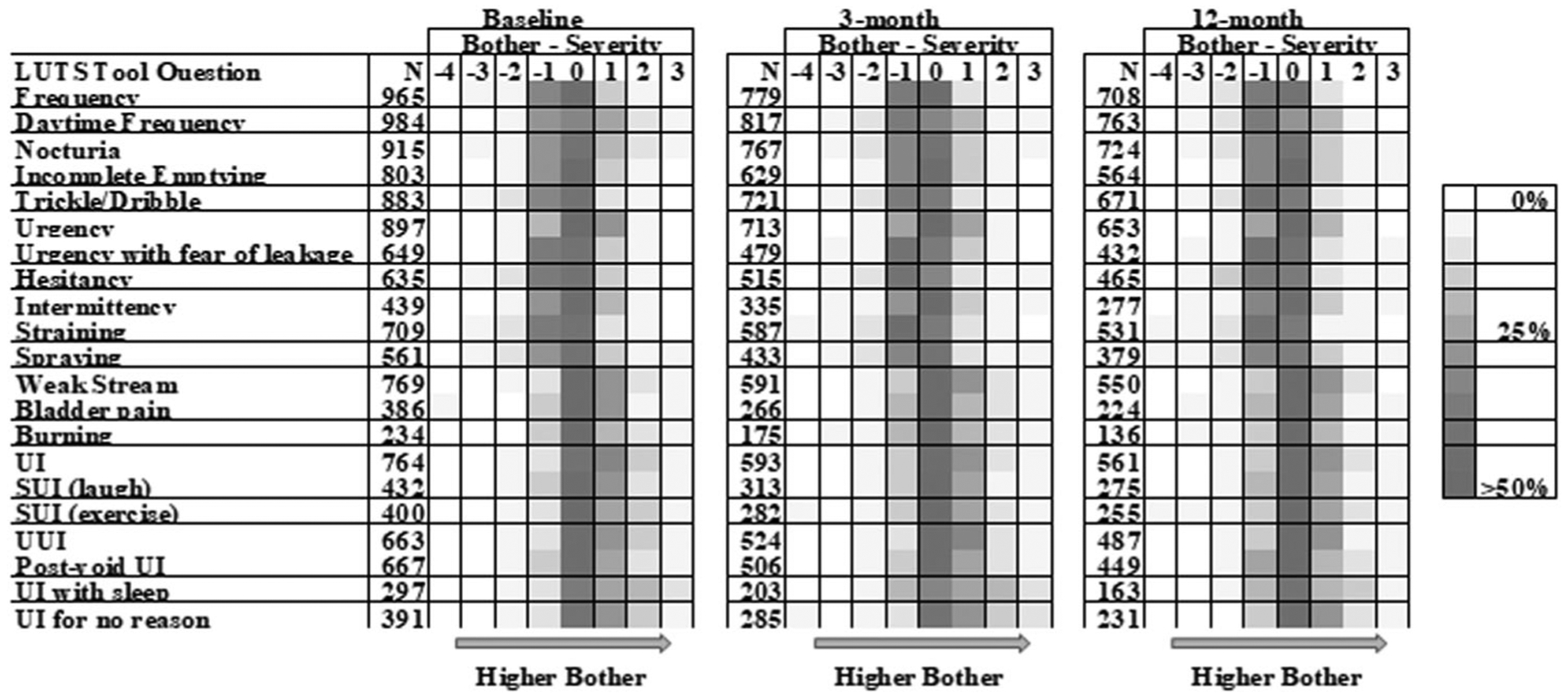

Differences in ratings for corresponding LUTS Tool severity and bother items across all three timepoints were centered around zero indicating concordance (i.e, no difference between severity and bother) and were consistent over time (Figure 2). Among the six LUTS Tool symptom groups, most patients rated their frequency, obstructive, and post-micturition symptoms more severe than bothersome and incontinence symptoms more bothersome than severe (Figure S2). Ratings for urgency and pain were largely concordant and these relationships were consistent over time.

FIGURE 2.

Differences between severity and bother at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months. Color map of differences between severity and bother. The difference was calculated as bother minus severity for each LUTS tool question and timepoint, so negative differences represent greater severity than bother and positive differences represent greater bother than severity. Each row represents a different LUTS tool questions and shows the relative frequency of differences using shades of gray, with darker shades representing higher frequency. LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; SUI, stress urinary ncontinence; UI, urinary incontinence

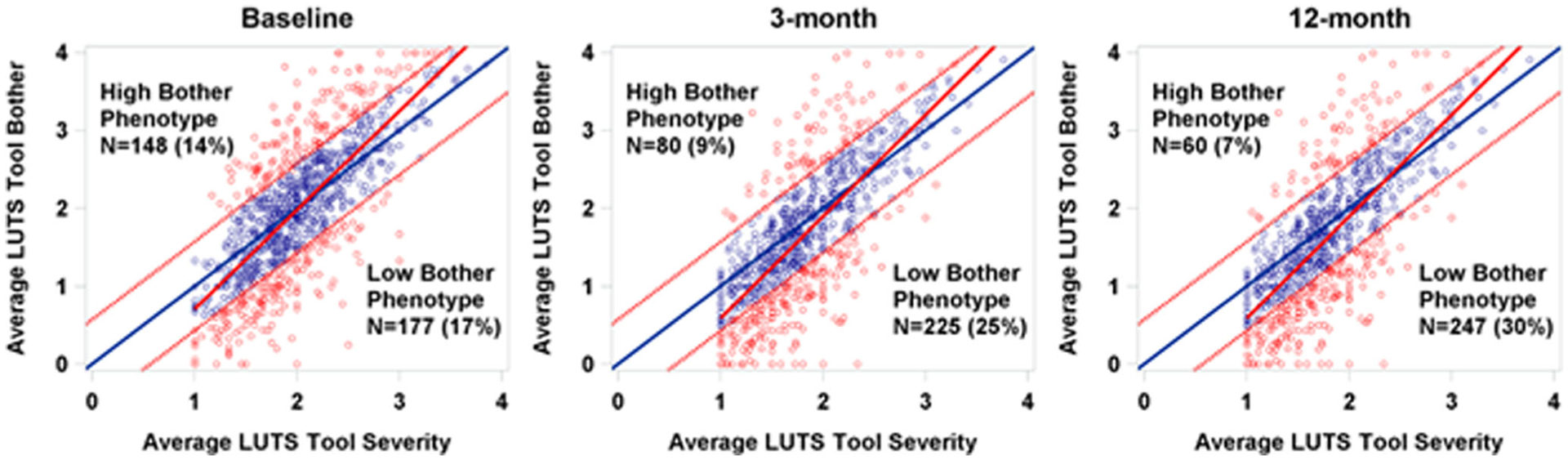

3.2.1 |. High and low bother phenotype

The relationship between overall average bother and severity ratings was mostly concordant across all timepoints, but with wide variability (Figure 3). At baseline, 14% and 17% of patients demonstrated high and low bother phenotypes, respectively.The prevalence of the high bother phenotype decreased to 9% at 3 months and 7% at 12 months, while the prevalence of the low bother phenotype increased to 25% at 3 months and 30% at 12 months. The majority of participants in the high bother phenotype shifted to the concordant bother phenotype at 12 months (61%), and a minority shifted to the lower bother phenotype at 12 months (9%). Lower odds of being in the high bother phenotype (vs concordant bother) was significantly associated with longer time from baseline (3 months OR = 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.54–0.94; 12 months OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.48–0.91) and older patient age (OR = 0.97 per year increase, 95% CI = 0.96–0.99; Table 2). Higher odds of being in the high bother phenotype (vs concordant bother) was significantly associated with higher GUPI total score (OR = 1.04 per unit increase, 95% CI = 1.04–1.08), and endorsement of all urgency questions (OR = 3.65, 95% CI = 2.17–6.13). Lower odds of being in the low bother phenotype (vs concordant bother) was significantly associated with higher GUPI total scores (OR = 0.91 per unit increase, 95% CI = 0.89–0.93), higher PROMIS sleep disturbance scores (OR = 0.98 per unit increase, 95% CI = 0.97–0.99), endorsement of all urgency questions (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.26–0.42), and endorsement of all frequency questions (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.53–0.88). The odds of being in the high or low bother phenotypes were not significantly associated with the PSS total score, and PROMIS gastrointestinal (GI) bowel incontinence, GI constipation, GI diarrhea, anxiety, depression, and physical function scores.

FIGURE 3.

High bother phenotype distribution by timepoint. Average LUTS tool severity versus average LUTS Tool bother at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months.Scatterplot of average LUTS Tool bother by average LUTS tool severity, paneled by timepoint. Average bother (and severity) were calculated as the sum of bother (severity) responses divided by the number of symptoms endorsed (ie, severity response of at least 1). Average discordance was calculated as average bother minus average severity, and patients with average discordance 1 standard deviation above (or below) zero were considered to be in the high (low) bother phenotype. Solid blue lines represents equal average bother and severity (ie, average discordance of zero), solid red lines represent simple linear regressions (SLR) of bother regressed on severity, dotted red lines represent cutoffs for high and low bother phenotypes, blue circles represent patients in the “concordant bother” phenotype, and red circles represent patients in either the high or low bother phenotypes. LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms

TABLE 2.

Repeated measures multinomial logistic regression evaluating the characteristics of the high and low bother phenotypes

| Probability of being in the “low bother” versus “concordant bother” phenotype | Probability of being in the “high bother” versus “concordant bother” phenotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio estimate | 95% Confidence interval | P value | Odds ratio estimate | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

| Visit (ref = baseline) | ||||||

| 3-mo | 1.173 | (0.891–1.544) | .2690 | 0.710 | (0.536–0.940) | .0273 |

| 12-mo | 1.265 | (0.989–1.619) | .0756 | 0.661 | (0.482–0.906) | .0180 |

| Age (per year increase) | 1.009 | (1.000–1.019) | .0728 | 0.973 | (0.962–0.985) | <.0001 |

| GUPI total (per unit increase) | 0.909 | (0.888–0.930) | <.0001 | 1.038 | (1.017–1.059) | .0007 |

| PROMIS sleep disturbance (per unit increase) | 0.980 | (0.966–0.994) | .0114 | 1.016 | (0.997–1.035) | .1209 |

| Endorsed all urgency questions (yes vs no) | 0.332 | (0.261–0.422) | <.0001 | 3.650 | (2.172–6.132) | <.0001 |

| Endorsed all frequency questions (yes vs no) | 0.683 | (0.533–0.876) | .0061 | 1.024 | (0.684–1.533) | .9077 |

Abbreviations: GUPI, genitourinary pain index; PROMIS, patient reported outcome measurement information system.

As a sensitivity analysis, the GUPI subscales were tested in separate models. The odds of being in the high or low bother phenotypes (vs concordant bother) for higher values of the subscale scores were all consistently in the same direction as the GUPI total score. All associations with probability of group membership for the subscale scores were statsically significant, except that the higher GUPI pain subscale score were not significantly associated with the odds of being in the high bother phenotype.

As a second sensitivity analysis, participants were classified into the high or low bother phenotype based on the fitted regression line for average severity and bother rather than the 45 degree line (ie, the solid red line in Figure 3 instead of the solid blue line). With this reclassification, 13% of participants were in the high bother phenotype and 14% were in the low bother phenotype at baseline. Factors associated with probability of group membership were similar except that higher GUPI total scores were not significantly associated with odds of being in the high bother phenotype. Otherwise, the magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of all effects remained consistent.

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this study, the correlation between severity and bother for 21 symptoms was at least moderately correlated at two of the three timepoints (baseline, 3 months, and 12 months) for men and women. LUTS severity and bother correlations were also strongly positive at the patient level. We also demonstrate that for most symptoms at two or more timepoints, LUTS severity and bother correlations were high. Collectively, these findings suggest that measurement of both severity and bother in a clinical setting is likely redundant for most individuals and for most symptoms. Individuals with urgency symptoms and those who endorse more pain, may require a closer evaluation of bother attributed to their symptoms.

Previous investigations have demonstrated convincingly that overall symptom severity and bother are highly correlated at baseline and least moderately correlated over a period of 5 years in community dwelling men.21 The current study clarifies this broader relationship by demonstrating that in a contemporary cohort inclusive of men and women seeking care for LUTS, the correlations between symptom severity and bother across 21 LUTS questions are consistent and at least moderately correlated at two of the three timepoints. All correlations were at least moderate, and two thirds were considered high (>0.7). The moderate correlations ranged from 0.57 to 0.69, and included symptoms of UI with sleep, UI for no reason, daytime frequency, nocturia, spraying, post-void UI, and dribbling. Though the correlations were moderate, there was still a notable correlation with bother. Moreover, for all of these symptoms, lower severity scores (rarely or sometimes) elicited the full range of bother ratings, indicating that for some even low severity was extremely bothersome. Many of these symptoms are common with aging and therefore may induce lower bother in older participants compared with younger participants, resulting in moderate correlations.

In this cohort, we also had a higher proportion of patients with high bother compared with community cohorts,21 which is likely due to the fact that this cohort is care-seeking. This supports current data that suggests bother from urinary symptoms is a primary driver of health care-seeking behavior.22 In our data, we observed that a majority of patients had symptom bother that matched symptom severity, as the majority of discordance scores (69%) were within a standard deviation of zero at baseline. This suggests that generally, symptom severity and/or symptom bother may potentially drive care-seeking and in real-world clinical settings, evaluation of either may be sufficient.

In this study, we observed that there were some patients with discordance between bother and severity. We found that 14% of patients had a high bother phenotype, while 17% of patients had a low bother phenotype. Our finding that individuals with a high bother phenotype endorsed more urgency symptoms and had higher GUPI scores suggests that urgency is a symptom which triggers treatment-seeking and is also consistent with findings reported by other population-based studies.2,23 A prior study in the LURN cohort at 12 months found worsened urinary quality of life in those with urinary urgency.24 Interestingly, we also noticed that over time and with increasing age, individuals were less bothered. This likely represents adaptation over time as opposed to treatment received. These individuals likely represent a shift into the low bother phenotype (9%), which we observed in this study. While evaluating treatment data was outside the scope of a this study, a prior study using this cohort demonstrated that everyone who received treatment did not demonstrate improvement at 12 months and some reported worse symptoms with treatment.25 This further supports the notion that symptom severity may be just as important as symptom bother in care-seeking populations. This may not be universally applicable in certain individuals considering patients’ expectations, response, and acceptance of treatments.

Limitations of this study include that this cohort is care-seeking and we do not evaluate treatment data. The fact that these individuals are care-seeking, however, makes them distinct as they are uniquely driven by the severity and/or bother of their symptoms, which makes our findings more applicable to clinical settings. The effect of treatment on these relationships will be the subject of future work. In addition, our cohort is more homogenous than a real-life cohort, which may limit generalizability. Lastly, there are numerous ranges available to characterize the strength of correlation coefficients beyond those used in this study, and a selection of different ranges may have an impact on the results presented.

These limitations notwithstanding, we uniquely and meticulously evaluated the longitudinal correlation and relationship between LUTS severity and bother for a constellation of LUTS in a cohort of care-seeking individuals and provided insight into the point at which individuals seek care for LUTS. This study has implications for patients, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system. While data consistently show that individuals are largely driven by LUTS bother to seek care, we demonstrate that LUTS severity is not a negligible aspect of symptom evaluation and may have equal bearing on why many individuals seek care for LUTS. In addition, we identify characteristics associated with discordance in bother and severity.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

At the sample and individual level, LUTS severity and bother values correlate highly, with little change over time. Though many of the patients had concordance between LUTS severity and bother, there is a subset of patients, however, with discordance between LUTS severity and bother (i.e., high and low bother phenotypes). Identification and characterization of these individuals with high bother phenotype may be useful to determine which individuals and which symptoms justify further evaluation. In most cases, however, given high concordance between severity and bother, measurement of both LUTS severity and bother is likely redundant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is publication number 26 of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN). This study is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grant numbers: DK097780, DK097772, DK097779, DK099932, DK100011, DK100017, DK099879). Research reported in this publication was supported at Northwestern University, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103(suppl 3):4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benner JS, Becker R, Fanning K, Jumadilova Z, Bavendam T, Brubaker L, OAB Medication Use Study Steering Committee. Bother related to bladder control and health care seeking behavior in adults in the United States. J Urol. 2009;181:2591–2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apostolidis A, de Nunzio C, Tubaro A. What determines whether a patient with LUTS seeks treatment? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarma AV, Wallner L, Jacobsen SJ, Dunn RL, Wei JT. Health seeking behavior for lower urinary tract symptoms in black men. J Urol. 2008;180:227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith JW, Messersmith EE, Gillespie BW, et al. Reasons for seeking clinical care for lower urinary tract symptoms: a mixed methods study. J Urol. 2018;199:528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarpero HM, Fiske J, Xue X, Nitti VW. American Urological Association Symptom Index for lower urinary tract symptoms in women: correlation with degree of bother and impact on quality of life. Urology. 2003;61:1118–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolters R, Wensing M, van Weel C, van der Wilt GJ, Grol RP. Lower urinary tract symptoms: social influence is more important than symptoms in seeking medical care. BJU Int. 2002;90:655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang CC, Weinfurt KP, Merion RM, Kirkali Z. Symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network. J Urol. 2016;196:146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coyne KS, Barsdorf AI, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron AP, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Smith AR, et al. Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network Study Group. Baseline lower urinary tract symptoms in patients enrolled in LURN: a prospective, observational cohort study. J Urol. 2018;199:1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiegel BM, Hays RD, Bolus R, et al. Development of the NIH patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 1804–1814;2104:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D, PROMIS Cooperative Group. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Urologic Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009;74:983–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, Van Hoewyk J IVEware: imputation and variance estimation software. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Methodology Program, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: a guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24:69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z Variable selection with stepwise and best subset approaches. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarma AV, Jacobsen SJ, Girman CJ, et al. Concomitant longitudinal changes in frequency of and bother from lower urinary tract symptoms in community dwelling men. J Urol. 2002;168:1446–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarma AV, Wei JT, Jacobson DJ, et al. Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status; Flint Men’s Health Study. Comparison of lower urinary tract symptom severity and associated bother between community-dwelling black and white men: the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status and the Flint Men’s Health Study. Urology. 2003;61:1086–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal A, Eryuzlu LN, Cartwright R, et al. What is the most bothersome lower urinary tract symptom? Individual- and population-level perspectives for both men and women. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu AB, Liu Q, Yang CC, et al. Patient characteristics associated with more bother from lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 2019;202:585–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amundsen CL, Helmuth ME, Smith AR, et al. LURN Study Group. Longitudinal changes in symptom-based female and male LUTS clusters. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.