Abstract

Abstract Background/Objective

Previous findings indicated that parents of children with developmental disabilities face greater care giving demands and report higher levels of stress. This study explores the styles and strategies of coping with stress among parents of children with developmental disabilities compared to parents of children with typical development.

Method

167 parents of children with developmental disabilities and 103 parents of typical development children participated as a voluntary. The CISS and the COPE Inventory were used to assess the coping styles and strategies in rearing a child.

Results

The results from Multivariate Analysis indicated significant differences between parents of children with and without developmental disabilities in one of three coping styles and one of eight coping strategies. Parents of children with developmental disabilities less often used the avoidance-oriented style and emotional support strategy. The task-oriented style and strategies were the dominant approach in both groups of parents. In stressful situations connected with rearing a child, parents of children with developmental disabilities do not use as dominant strategies connected with seeking emotional support and religion, which occur in the parents of typical development children.

Conclusions

The results suggest areas where coping may be different than in families of children without DD.

KEYWORDS: Coping strategies, Coping styles, Developmental disabilities, Parenting, Ex post facto study

Abstract

Resumen Antecedentes/Objetivo

Investigaciones previas muestran que los padres con hijos que padecen trastornos del desarrollo deben hacer frente a mayores demandas de atención y reportan mayor estrés. El presente estudio compara los estilos y estrategias de afrontamiento del estrés utilizados de los padres de hijos con trastornos del desarrollo con los utilizados por padres de hijos con desarrollo típico.

Método

Participaron 167 padres de niños con trastornos del desarrollo y 103 padres de niños que muestran un desarrollo típico. Los inventarios CISS y COPE se utilizaron para evaluar los estilos y estrategias de afrontamiento.

Resultados

Los resultados indicaron diferencias significativas entre los padres de hijos con y sin trastornos del desarrollo en uno de los tres estilos de afrontamiento y una de las ocho estrategias, utilizando con menos frecuencia el estilo orientado a la evitación y la estrategia de apoyo emocional, siendo los orientados a la tarea el enfoque dominante. En situaciones estresantes, los padres de niños con trastornos del desarrollo no utilizaron las estrategias de búsqueda de apoyo emocional o la religión.

Conclusiones

Los resultados sugieren un afrontamiento diferente al de las familias con hijos sin discapacidades.

Parents of children with developmental disabilities (DD) find themselves in a unique psychosocial situation. Previous findings indicate that these parents, compared with the parents of children with typical development (TD), face greater care giving demands and report higher levels of stress (Cuzzocrea et al., 2016), anxiety (Antonopoulou et al., 2020), future anxiety (Bujnowska, Rodriguez, Garcia, Areces, & Marsh, 2019) and depression (Scherer et al., 2019).

The foregoing study is based on the concept of coping with stress by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) with the concept of Carver et al. (1989) based on it and coping is understood as a group of behavioural or cognitive efforts used by an individual to minimize their level of distress. Coping styles are defined as ways of responding in stressful situations (Strelau et al., 2005). Coping strategies, in turn, are specific reactions that an individual undertakes or activates, depending on a specific stressful situation. For its part, Coping pattern, is a set of different forms of struggling with a difficult situation, which an individual applies to increase the effectiveness of their own preventive measures.

In this sense, Endler and Parker (1990) distinguished three major categories of coping styles: (1) problem-oriented coping, the style of coping with stress involving directly solving the problem or changing the source of stress; (2) emotion-oriented coping – the style, which is typical of the behaviors of people who, in stressful situation tend to focus on themselves and their own emotional experiences; and (3) avoidance-oriented, when an individual does not aim at confrontation with the problem, but tends to avoid thinking and experiencing that situation (Strelau et al., 2005).

The model by Carver et al. (1989) contains many separate behaviours and coping strategies, which people undertake to cope in a specific stressful situation, such as: positive reinterpretation and growth, mental disengagement, focus on and venting of emotions, use of instrumental social support, among other. In this line, although most studies reveal greater intensity of non-adaptive styles among parents bringing up a child with DD, compared to parents bringing up TD children (Vernhet et al., 2019), other reports reveal that mothers of children with autism use engagement and cognitive reframing coping styles more often than mothers in the TD group (Obeid & Daou, 2015). Another study revealed that there were not differences in coping strategies between DD and TD parents (Antonopoulou et al., 2020).

Similarly, more frequent application of strategies focused on problems by parents of DD children provided mental well-being to them and lower stress symptoms (Hsiao, 2018; Shneider et al., 2020; Vernhet et al., 2019). Cognitive coping of parents with autistic children revealed a relationship with their higher level of well-being (Obeid & Daou, 2015), whereas applying accommodative coping generated their higher well-being and higher level of controlling the environment (Seltzer et al., 2004). Other findings suggest that child behaviour difficulties may contribute to parental fatigue, which in turn may influence use of ineffective coping strategies and increased stress and the anxiety levels (Antonopoulou et al., 2020).

In the families of children with DD taking more advantage of the strategy of coping with emotions is connected with lower degree of well-being and subjective burden and active avoidance coping was related to more stress and mental health problems (Medina-Mora et al., 2019; Shokoohi-Yekta et al., 2015). Distraction and disengagement coping predicted poorer well-being among mothers of children with autism (Obeid & Daou, 2015), and emotion-oriented strategies were positively correlated with anger (Shokoohi-Yekta et al., 2015).

Considering the previous studies mentioned, this study aims to respond the following questions: (1) What are the differences in the coping styles and coping strategies in parents of children with DD in comparison to parents of children with TD? (2) What is the coping style pattern and coping strategy pattern within the group of parents of children with DD and within the group of parents of children with TD? And, (3) What styles and strategies of coping are predominant, and which are applied the least frequently?

Method

Participants

Participants were 270 parents (67% mothers and 33% fathers) divided into two groups of parents of children with DD (n = 167) and parents of children with TD (n = 103). Inclusion criteria for parents were as follows: (a) at least one child aged between 2 and 16 years of age; and (b) the child was living at home. For parents with children with DD the criteria included that their child was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), sensory disabilities (SD) or Intellectual disability (ID) according to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association APA, 2013).

Age of parents was in range from 22 to 54 (M = 37.6, SD = 8.94). Most of the participants across both groups of parents were women (65% DD; 71% TD), married (87% DD; 88.35% TD), lived in the big or medium-size cities (64.7% DD; 70% TD), completed a University degree (Bachelor or Master´s) (53% DD; 71% TD), and had one child (65% DD; 52% TD). Their children with DD had a mean age of 8.29 years (SD = 4.10, range = 2-16 years). The majority (n = 137, 82%) were male. The types of DD for the children were SD (n = 47, 28%), ID (n = 30, 18%) and ASD (n = 90, 54%).

Procedure

Parents were recruited through randomly chosen thirteen educational institutions in Eastern Poland such as: kindergartens, primary schools and special centres and schools for children with disability. The study took place at the educational centres during the parents’ meetings after the first semester of the school year. Data collection occurred in groups of up to 25 participants, within a 30-minute time frame. The study met ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration (Williams, 2008) and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias (COPRAMO 240/18). Participation in the study was voluntary, and the anonymity and ethical treatment of the data were guaranteed.

Instruments

The CISS-Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations of Endler and Parker (1990) assesses coping styles. The present study employed the 48-item Polish version of the CISS (Strelau et al., 2005). Items cover different aspects of human behaviour as negative or positive statements using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (very often). The CISS provides three scores: Task-oriented, Emotion-oriented and Avoidance-oriented. Each subscale consists of 16 items. Higher scale scores indicate higher intensity of coping style. Satisfactory indicators of reliability and validity of the Polish version of the CISS were found. In the present sample, high internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach alpha) were found for each subscale: Task-oriented style (α = .86), Emotion-oriented style (α = .87) and Avoidance-oriented style (α = .81).

The COPE-Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced was developed by Carver et al. (1989) to assess the maladaptive and adaptive coping strategies. To define the strategies of the parents’ coping in the situation of child rearing, the procedure proposed by Carver et al. (1989) was applied. We used the 60-item Polish inventory adaptation by Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik (2009), divided into 15 subscales. The items ranging from 1 (I usually don't do this at all) to 4 (I usually do this a lot). Each subscale consists of 4 items. The possible values for each subscale range from 4 to 16 and higher scale scores indicate higher intensity of coping strategy. In the present sample, high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach alpha) were found for 8 of the 15 subscales and they are included in further analyses: Planning (α = .71) and Use of instrumental social support (α = .81) as a problem-oriented strategies; Use of emotional social support (α = .79), Religious coping (α = .86), Acceptance (α = .71) and Focus on and venting of emotions (α = .75) as an emotion-oriented strategies; Substance use (α = .83) and Humor (α = .70) as an avoidance-oriented strategies. For 7 of the 15 subscales were found to be unreliable, with reliability lower than α < .70, and they were excluded from further statistical analysis.

Data analysis

Prior to the main analyses, exploratory analyses were conducted to verify the normality of the sampling distribution. The distributions of dependent variables were investigated with q-q plots, Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests and computations of skewness and kurtosis, not observing severe deviations from normality. Multivariate Analysis of Variance were calculated with parent group variable as factor separately for CISS and COPE dimensions. Additionally, to examine the interaction effects first we investigated differences in coping styles and strategies between parents and parent group using pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. These last analyses were preceded with repeated measures analyses of variance (where coping style or strategy were treated as repeated measurement).

As a measure of effect size for the analyses of variance partial eta-squared was calculated, interpreted as small (partial η2 < .01), medium (partial η2 = .01 to 0.1) and large (partial η2 > .1) (Kinnear & Gray, 2004). To determine the effects’ magnitudes for comparisons of two groups we used Cohen's d, interpreted as: no effect (d < 0.09), small (d = 0.10 to 0.49), medium (d = 0.50 to 0.79) and large (d ≥ 0.80) (Cohen, 1988). Data processing and the statistical analyses were carried out with IMB SPSS Statistics 25.

Results

Equivalence of groups

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups of parents on gender, age group, relationship status and the average number of children in family. Parents of children with TD were more likely (71%) than parents of children with DD (53%) to have completed tertiary (postsecondary) education (χ2(1) = 8.74, p = .003). Similarly, parents of children with TD were more likely (84%) than parents of children with DD (36%) to live in households where both adults were employed (χ2(1) = 59.11, p < .001).

Coping styles (CISS Inventory)

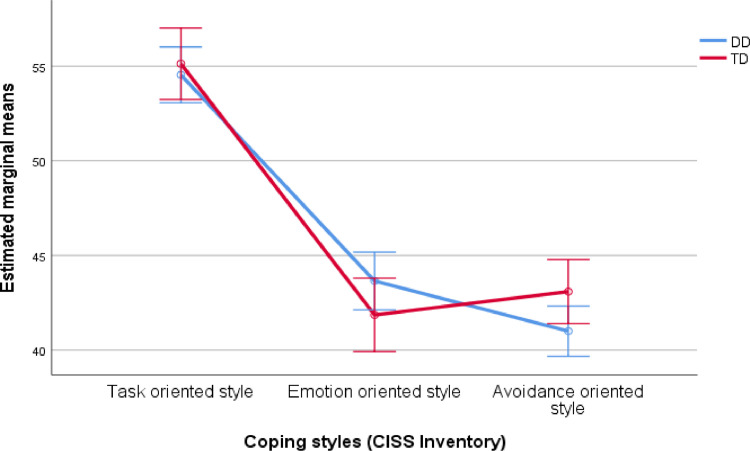

Results of the multivariate test indicated that mean levels of coping styles differed significantly, V(s) = .51, F(2, 267) = 139.36, p < .001, partial η2 = 0.511. Significant interaction of parent group and CISS dimensions indicating that differences in coping styles within parent groups differ, V(s) = .03, F(2, 267) = 4.55, p = .011, partial η2 = .033, with medium effect size. Interaction effect between parent showed that of the three dimensions of coping styles examined, statistically significant differences were found only in one (Table 1). Parents of DD children reported significantly lower level of Avoidance-orientation copy style than parents of TD children (Figure 1). The magnitude of the effect size was small.

Table 1.

Results of pairwise comparisons of the CISS dimensions between parent groups.

| Coping style type | Comparison | Difference of means | SE | 95% Cis |

p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LI | UI | ||||||

| Task oriented | DD - TD | -0.59 | 1.22 | -2.98 | 1.81 | .629 | - |

| Emotion oriented | 1.79 | 1.25 | -0.67 | 4.26 | .154 | - | |

| Avoidance oriented | -2.09 | 1.09 | -4.24 | 0.06 | .057 | 0.24 | |

Note. p values computed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. The Leven test of equality of variances between parent groups was not significant for any of the CISS dimensions (all p > .438).

Figure 1.

Estimated marginal means of the CISS inventory dimensions for the parents of children with DD and parents of TD children.

Note. Vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals of the estimated marginal means.

Additionally, the possible effect of some children characteristics (type of disability and age) and parent characteristics (gender, age, marital status, and employment) on CISS styles was analyzed. Such differences were found in the case of parents´ age, V(s) = .32, F(3, 266) = 2.88, p = .036, partial η2 = .032, with medium effect size. In this case, younger parents (till 40 years old) showing statistically significant scores in task-oriented, F(3, 268) = 4.61, p = .033, partial η2 = .017, and avoidance-oriented, F(3, 268) = 4.59, p = .033, partial η2 = .017.

Comparison of coping styles levels within parent groups (Table 2) revealed a significant differences between dimensions of copy styles within Parent group DD, V(s) = .42, F(2, 267) = 96.72, p < .001, partial η2 = .42, as well as within the Parent group TD, V(s) = .30, F(2, 267) = 56.68, p < .001, partial η2 = .3, with a large effect size. Within parents of DD children all the compared dimensions differed, with the large effect size for Task vs. Emotion and Task vs. Avoidance oriented strategies, and with small effect size for Emotion vs. Avoidance oriented strategies. Task-oriented style had the highest average level and Avoidance-orientated style had the lowest average level. Within the parents of TD children, the Task-oriented style was also dominant (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Results of pairwise comparisons within parent groups between the CISS dimensions.

| Parent group | Comparison | Difference of means | SE | 95% Cis |

p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LI | UI | ||||||

| DD | Task vs. Emotion oriented | 10.89 | 1.05 | 8.36 | 13.42 | <.001 | 1.08 |

| Task vs. Avoidance oriented | 13.54 | 0.97 | 11.19 | 15.89 | <.001 | 1.48 | |

| Emotion vs. Avoidance oriented | 2.65 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 4.56 | .003 | 0.28 | |

| TD | Task vs. Emotion oriented | 13.27 | 1.34 | 10.05 | 16.49 | <.001 | 1.39 |

| Task vs. Avoidance oriented | 12.04 | 1.24 | 9.05 | 15.03 | <.001 | 1.29 | |

| Emotion vs. Avoidance oriented | -1.23 | 1.01 | -3.66 | 1.20 | .669 | - | |

Note. p values computed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison.

Coping strategies (COPE Inventory)

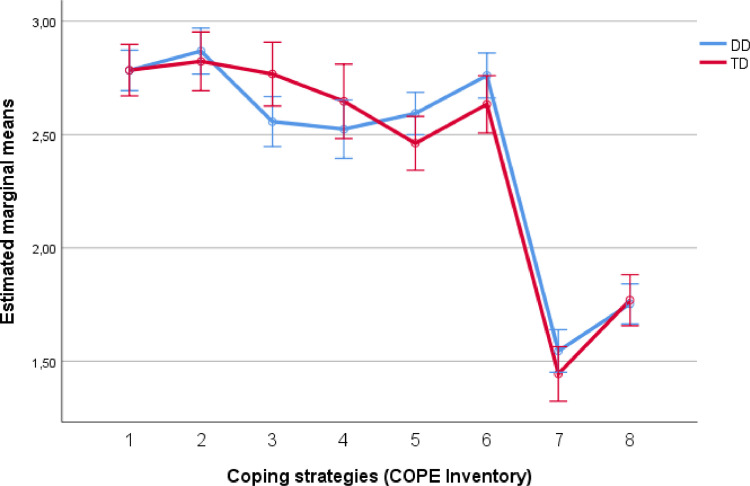

Results of the multivariate test indicated that mean levels of coping strategies strong differed significantly, V(s) = .71, F(7, 262) = 90.29, p < .001, partial η2 = .71. In line with our predictions we observed significant interaction of parent group and COPE dimensions indicating that differences in coping strategies within parent groups differ, V(s) = .09, F(7, 262) = 3.78, p = .001, partial η2 = .092 with medium effect size. Interaction effect showed differences in coping strategies between group of parents with DD child and with TD child. Parent differences were significant only for one of the 8 dimensions of coping strategies (Table 3). Parents of DD children reported significantly lower level of seeking Emotional Support as a coping strategy than parents of TD children (Figure 2). The magnitude of the effect size was small.

Table 3.

Results of pairwise comparisons of the COPE dimensions between parent groups.

| COPE dimensions | Comparison | Difference of means | SE | 95% Cis |

p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LI | UI | ||||||

| Planning | DD - TD | 0.00 | 0.07 | -0.15 | 0.14 | .989 | - |

| Instrumental support | 0.05 | 0.08 | -0.12 | 0.21 | .587 | - | |

| Emotional support | -0.21 | 0.09 | -0.39 | -0.03 | .022 | 0.29 | |

| Religion | -0.12 | 0.11 | -0.33 | 0.09 | .250 | - | |

| Acceptance | 0.13 | 0.08 | -0.02 | 0.28 | .088 | - | |

| Focus on emotions | 0.13 | 0.08 | -0.03 | 0.29 | .121 | - | |

| Substance use | 0.10 | 0.08 | -0.05 | 0.25 | .195 | - | |

| Humor | -0.02 | 0.07 | -0.16 | 0.13 | .822 | - | |

Note. p values computed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. The Leven test of equality of variances between parent groups was not significant for any of the COPE dimensions (all p > .05).

Figure 2.

Marginal Means of the COPE inventory dimensions for parents with DD children and parents with TD children.

Note. Vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals of the estimated marginal means;1- planning, 2 – instrumental support, 3 – emotional support, 4 – religion, 5 – acceptance, 6 – focus on emotions, 7 – substance use, 8 – humor.

Concerning the effect of children and parent characteristics on COPE, again, results showed that there were statistically significant differences regarding parents´ age, V(s) = .099, F(15, 254) = 1.86, p = .027, partial η2 = .099, with medium effect size. Again, younger parents showed higher and statistically significant scores in planning, F(1, 268) = 6.04, p = .015, partial η2 = .022, use of instrumental social support, F(1, 268) = 5.22, p = .023, partial η2 = .019, and focus on emotions, F(1, 268) = 6.06, p = .014, partial η2 = .022, with medium effect sizes.

Next, we found (Table 4) differences between dimensions of coping strategy within the group of parents with DD child, V(s) = .62, F(7, 262) = 62.48, p < .001, partial η2 = .625, as well as within the TD parent group, V(s) = .50, F(7, 262) = 37.51, p < .001, partial η2 = .501. In both, the magnitude of the effect size was large. Details of the pairwise comparisons within the DD parent group are provided in Table 4 and within the TD parent group in Table 5 (see also Figure 2 for estimated marginal means).

Table 4.

Results of pairwise comparisons within DD parent group between the COPE dimensions

| MD | SE | 95% Cis |

p | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPE dimensions | LI | UI | |||||

| Planning | Instrumental support | -0.09 | 0.05 | -0.25 | 0.08 | 1.000 | - |

| Emotional support | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.41 | .004 | 0.34 | |

| Religion | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.49 | .011 | 0.35 | |

| Acceptance | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.37 | .026 | 0.32 | |

| Focus on emotions | 0.02 | 0.06 | -0.15 | 0.20 | 1.000 | - | |

| Substance use | 1.24 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 1.46 | <.001 | 2.03 | |

| Humor | 1.03 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 1.23 | <.001 | 1.76 | |

| Instrumental support | Emotional support | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.44 | <.001 | 0.43 |

| Religion | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.58 | <.001 | 0.44 | |

| Acceptance | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.46 | <.001 | 0.42 | |

| Focus on emotions | 0.11 | 0.05 | -0.04 | 0.26 | .698 | - | |

| Substance use | 1.32 | 0.07 | 1.10 | 1.55 | <.001 | 1.98 | |

| Humor | 1.12 | 0.07 | 0.88 | 1.35 | <.001 | 1.73 | |

| Emotional support | Religion | 0.03 | 0.08 | -0.21 | 0.27 | 1.000 | - |

| Acceptance | -0.04 | 0.06 | -0.23 | 0.6 | 1.000 | - | |

| Focus on emotions | -0.20 | 0.05 | -0.37 | -0.04 | .003 | 0.31 | |

| Substance use | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 1.25 | <.001 | 1.54 | |

| Humor | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 1.05 | <.001 | 1.27 | |

| Religion | Acceptance | -0.07 | 0.08 | -0.32 | 0.18 | 1.000 | - |

| Focus on emotions | -0.24 | 0.08 | -0.48 | 0.01 | .064 | - | |

| Substance use | 0.98 | 0.08 | 0.71 | 1.24 | <.001 | 1.31 | |

| Humor | 0.77 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 1.01 | <.001 | 1.06 | |

| Acceptance | Focus on emotions | -0.17 | 0.06 | -0.35 | 0.02 | .134 | - |

| Substance use | 1.05 | 0.07 | 0.84 | 1.26 | <.001 | 1.72 | |

| Humor | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.64 | 1.04 | <.001 | 1.43 | |

| Focus on emotions | Substance use | 1.22 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 1.43 | <.001 | 1.97 |

| Humor | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 1.24 | .001 | 1.70 | |

| Substance use | Humor | -0.21 | 0.05 | -0.36 | -0.06 | .001 | 0.35 |

Note. MD = Mean Differences; p values computed with Bonfferoni correction for multiple comparison.

Table 5.

Results of pairwise comparisons within TD parent group between the COPE dimensions.

| MD | SE | 95% Cis |

p | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPE dimensions | LI | UI | |||||

| Planning | Instrumental support | -0.04 | 0.07 | -0.25 | 0.17 | 1.000 | - |

| Emotional support | 0.02 | 0.07 | -0.22 | 0.25 | 1.000 | - | |

| Religion | 0.14 | 0.09 | -0.15 | 0.43 | 1.000 | - | |

| Acceptance | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.55 | <.001 | 0.52 | |

| Focus on emotions | 0.15 | 0.07 | -0.08 | 0.38 | 1.000 | - | |

| Substance use | 1.34 | 0.09 | 1.06 | 1.62 | <.001 | 2.31 | |

| Humor | 1.02 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 1.27 | <.001 | 1.76 | |

| Instrumental support | Emotional support | 0.06 | 0.05 | -0.10 | 0.22 | 1.000 | - |

| Religion | 0.18 | 0.10 | -0.12 | 0.48 | 1.000 | - | |

| Acceptance | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.60 | <.001 | 0.57 | |

| Focus on emotions | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.38 | .058 | - | |

| Substance use | 1.38 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 1.67 | <.001 | 2.30 | |

| Humor | 1.05 | 0.09 | 0.76 | 1.35 | <.001 | 1.76 | |

| Emotional support | Religion | 0.12 | 0.10 | -0.18 | 0.42 | 1.000 | - |

| Acceptance | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.56 | .004 | 0.43 | |

| Focus on emotions | 0.13 | 0.07 | -0.08 | 0.34 | 1.000 | - | |

| Substance use | 1.32 | 0.09 | 1.03 | 1.62 | <.001 | 1.94 | |

| Humor | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.69 | 1.31 | <.001 | 1.47 | |

| Religion | Acceptance | 0.19 | 0.10 | -0.13 | 0.50 | 1.000 | - |

| Focus on emotions | 0.01 | 0.10 | -0.30 | 0.32 | 1.000 | - | |

| Substance use | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.87 | 1.54 | <.001 | 1.67 | |

| Humor | 0.88 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 1.19 | <.001 | 1.23 | |

| Acceptance | Focus on emotions | -0.17 | 0.08 | -0.41 | 0.06 | .628 | - |

| Substance use | 1.02 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 1.28 | <.001 | 1.64 | |

| Humor | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.94 | <.001 | 1.12 | |

| Focus on emotions | Substance use | 1.19 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 1.47 | <.001 | 1.82 |

| Humor | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 1.16 | <.001 | 1.33 | |

| Substance use | Humor | -0.33 | 0.06 | -0.52 | -0.13 | <.001 | 0.56 |

Note. p values computed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison.

To facilitate interpretation of the results, all compared dimensions of coping strategy by parents of children with DD we divided into four main groups. The first group - dominated coping strategies - contains three strategies the most often used by parents of children DD: Instrumental support (M = 2.87, SD = 0.70), Planning (M = 2.78, SD = 0.59) and Focus on emotion (M = 2.76, SD = 0.61). There were no significant differences in pairwise comparisons of these strategies and each of them significant differed from COPE dimensions from second, third and fourth group. The second group - often used strategies – contains three dimensions: Acceptance (M = 2.59, SD = 0.59), Emotional support (M = 2.56, SD = 0.69) and Religion (M = 2.52, SD = 0.85). The third group - rarely used strategies - includes one dimension, Humor, that differs significantly from 6 dimension with large effect size and from one COPE dimensions with small effect size. The fourth group - the least used strategies - contains also only one Substance use strategy, which differs significantly from all strategies of the first and second group with large effect size and from strategy of third group with small effect size (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Among TD parents (Table 5 and Figure 2), like in the DD parent, we formed coping strategies into four groups. The first group - dominated coping strategies - contains five strategies the most often used by parents of children TD: Instrumental support (M = 2.82, SD = 0.61), Planning (M = 2.78, SD = 0.57), Emotional support (M =2.77, SD = 0.77), Religion (M = 2.65, SD = 0.84) and Focus on emotion (M =2.63, SD = 0.71). The second group - often used strategies – contains one dimension: Acceptance. The third and fourth group - rarely used and the least used strategies - are the same as among parents of DD and its differs significantly from all strategies of the first and second group with large effect size.

Discussion

In our study it was analyzed the coping with stress by parents of children with DD compared to the parents of TD children. The results of current study partially confirmed the hypotheses concerning the differences in the intensity of coping styles and strategies between parents of DD and TD. In contrast to previous studies (Ganjiwale et al., 2016; Vernhet et al., 2019), this study revealed that parents of children with DD, compared to parents of children with TD, present a significantly lower intensity index of non-adaptive way of coping, which is Avoidance-oriented style, also showing a simultaneous similar level of Task-oriented style and Emotional-oriented style.

More specifically, the comparison of coping styles and coping strategy levels showed that Coping Style Pattern in the group of parents with DD children turned out to be the following: Task-oriented style (as the predominant style) - Emotional-oriented style (as the moderate style) - Avoidance-oriented style (as the least present style), whereas in the group of TD parents – Task-oriented style (as the predominant style) - Emotional-oriented style with Avoidance-oriented style (as the moderate style). These results are linked with research obtain among parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder (Pepperell et al., 2018). Other research suggests that greater use of problem-focused cope and lower emotion-focused, predicts lower depressive symptoms and higher parenting efficacy among mothers of DD adolescents (Woodman & Hauser-Cram, 2013).

The above findings may come from the specificity of the functioning of families rearing a child with disability and more difficult care giving challenges than in TD families (Antonopoulou et al., 2020; Cuzzocrea et al., 2016; Scherer et al., 2019). It is common that parents of DD get involved not only in care and upbringing, but also in everyday rehabilitation and education of the child, which might be related to the adoption of a more “instrumental” – task oriented- approach (Strelau et al., 2005).

Moreover, our research shows that younger parents are much more likely than older parents to use of problem-focused coping in general situations (task-oriented style) and those connected with care giving and upbringing of a child (planning strategy and use of instrumental support). These results, indicate a fairly high emotional cost, which may be resulting from lower parental sense of competence, more common for younger parents, and also are characterized by a significantly higher tendency to avoid difficult situations (Strelau et al., 2005).

Thus, the parents of DD, encountering difficult situations, related to child rearing are definitely less oriented to obtaining emotional support from others. They also less frequently seek moral support, friendliness, sympathy or understanding compared to parents of TD (Bawalsah, 2016; Halstead et al., 2018; Vernhet et al., 2019). This pattern would also results into a lower intensity of avoidance strategies than in the parents of TD, as the main focus is taking care of the child. These findings are important since they might explain a higher co-existence of depression in this group of parents than in TD parents, which may correlate with social withdrawal (Lai et al., 2015). Social support is indeed a protective factor concerning emotional problems and low self-perceived life satisfaction, and it could be a significant element in building effective support programs for that group of parents (Akturk & Aylaz, 2017; Halstead et al, 2018; Salas et al., 2017).

Also interesting, parents of children with DD did not show in their repertoire the predominant strategies connected with seeking emotional support in religion, which occur in the parents of TD children. At this respect, the religious coping strategy can be considered as non-adaptive strategies (Shokoohi-Yekta et al., 2015) by parents. Other researchers, however, indicate the advantageous significance of religious support (Carver et al., 1989; Isa et al., 2017). However, the results of previous studies among children with different kinds of DD are mixed in this sense (Amireh, 2019; Beighton & Wills, 2017).

To sum up, the results of the present study demonstrates that the parents of DD have a personal resource in the form of constructive coping with stress both in general situations and those connected with care giving and upbringing of a child with DD (Hsiao, 2018; Vernhet el al., 2019). Additional variables, such as the degree and type of implication of the parents in the daily care and rehabilitation of the child, their degree of training and the access to specific resources, the real social support network they have, and the religious orientation of the family should be considered in further studies as both possible predictor or moderator variables in the relationship between parenting of a DD child and coping strategies. Also, the emotional profiles of parents should be also examined, specially the presence of depression and/or anxiety, related to low social participation (de Moor et al., 2018).

Finally, it is important to highlight two main limitations in the present study. First, sample size and characteristics of the sample, which affects the generality of the findings. And second, this research is cross-sectional, examining parent coping at only one point in time, so does not considered as a dynamic process that changes over time as the child with DD and his or her family also change.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Sciences and Innovation I+D+i project with reference PID2019-107201GB-100 and Principality of Asturias, regional project with reference FC-GRUPIN-IDI/2018/000199.

References

- Akturk U., Aylaz R. An evaluation of anxiety in parents with disabled children and their coping strategies. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2017;10:342–353. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association APA . 5th ed. Author; 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Amireh M.M.H. Stress levels and coping strategies among parents of children with autism and down syndrome: The effect of demographic variables on levels of stress. Child Care in Practice. 2019;25:146–156. doi: 10.1080/13575279.2018.1446907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulou K., Manta N., Maridaki-Kassotaki K., Kouvava S., Stampoltzis A. Parenting and Coping Strategies among Parents of Children with and without Autism: The Role of Anxiety and Emotional Expressiveness in the Family. Austin Journal of Autism & Related Disabilities. 2020;6 Article e1054. [Google Scholar]

- Bawalsah J.A. Stress and coping strategies in parents of children with physical, mental, and hearing disabilities in Jordan. International Journal of Education. 2016;8:1–22. doi: 10.5296/ije.v8i1.8811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton C., Wills J. Are parents identifying positive aspects to parenting their child with an intellectual disability or are they just coping? A qualitative exploration. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2017;21:325–345. doi: 10.1177/1744629516656073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujnowska A.M., Rodriguez C., Garcia T., Areces D., Marsh N.V. Parenting and future anxiety: The impact of having a child with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Scheier M.F., Weintraub J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56 doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. Article e267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J.W. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Assiociates; 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea F., Murdaca A.M., Costa S., Filippello P., Larcan R. Parental stress, coping strategies and social support in families of children with a disability. Child Care in Practice. 2016;22:3–19. doi: 10.1080/13575279.2015.1064357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Moor E.L., Denollet J., Laceulle O.M. Social inhibition, sense of belonging and vulnerability to internalizing problems. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;225:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler N.S., Parker J.D. State and trait anxiety, depression and coping styles. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1990;42:207–220. doi: 10.1080/00049539008260119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganjiwale D., Ganjiwale J., Sharma B., Mishra B. Quality of life and coping strategies of caregivers of children with physical and mental disabilities. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2016;5:343–348. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead E.J., Griffith G.M., Hastings R.P. Social support, coping, and positive perceptions as potential protective factors for the well-being of mothers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2018;64:288–296. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2017.1329192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao Y.J. Parental stress in families of children with disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic. 2018;53:201–205. doi: 10.1177/1053451217712956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isa S.N.I., Ishak I., Rahman Ab, A. Saat, N. Z.M., Din N.C., Lubis S.H., Ismail M.F.M. Perceived stress and coping styles among Malay caregivers of children with learning disabilities in Kelantan. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2017;24:81–93. doi: 10.21315/mjms2017.24.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński Z., Ogińska-Bulik N. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych; 2009. Narzędzia pomiaru stresu i radzenia sobie ze stresem [Tools for measuring stress and coping with stress] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnear P.R., Gray C.D. Taylor & Francis; 2004. SPSS 12 made simple. [Google Scholar]

- Lai W.W., Goh T.J., Oei T.P., Sung M. Coping and well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:2582–2593. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus M., Folkman S. Springer; 1984. Stress, appraisal and coping. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora M.E., Robles R., Rebello T.J., Domínguez T., Martínez N., Juárez F., Sharan P., Reed G.M. ICD-11 guidelines for psychotic, mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders in Mexico: Clinical utility and reliability. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2019;19:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid R., Daou N. The effects of coping style, social support, and behavioral problems on the well-being of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders in Lebanon. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;10:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperell T.A., Paynter J., Gilmore L. Social support and coping strategies of parents raising a child with autism spectrum disorder. Early Child Development and Care. 2018;188:1392–1404. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1261338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salas B.L., Rodríguez V.Y., Urbieta C.T., Cuadrado E. The role of coping strategies and self-efficacy as predictors of life satisfaction in a sample of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Psicothema. 2017;29:55–60. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2016.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer N., Verhey I., Kuper H. Depression and anxiety in parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219888. Article e0219888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E.E., Schönfelder S., Domke-Wolf M., Wessa M. Measuring stress in clinical and nonclinical subjects using a German adaptation of the perceived stress scale. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2020;20:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer M.M., Greenberg J.S., Floyd F.J., Hong J. Accommodative coping and well-being of midlife parents of children with mental health problems or developmental disabilities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:187–195. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokoohi-Yekta M., Ghobary-Bonab B., Malayeri S.A., Zamani N., Pourkarimi J. The relationship between anger and coping strategies of mothers of children with special needs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015;205:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strelau J., Jaworowska A., Wrześniewski K., Szczepaniak P. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych; Warszawa: 2005. Kwestionariusz radzenia sobie w sytuacjach stresowych CISS. Podręcznik [Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations CISS. Manual] [Google Scholar]

- Vernhet C., Dellapiazza F., Blanc N., Cousson-Gélie F., Miot S., Roeyers H., Baghdadli A. Coping strategies of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2019;28:747–758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.R. Revising the Declaration of Helsinki. World Medical Journal. 2008;54:120–122. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman A.C., Hauser-Cram P. The role of coping strategies in predicting change in parenting efficacy and depressive symptoms among mothers of adolescents with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2013;57:513–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]