Three demographic trends are colliding to form a perfect storm that challenges the health and wellbeing of the population: The post-retirement portion of the population is swelling; the human lifespan is lengthening; the birth-rate is dropping. The result is that the support ratio—the balance of young-to-old—is shifting, leaving fewer young workers to drive the economy and pay taxes to support more aging citizens (https://www.populationpyramid.net). These three trends mean more stress for the young and less support for the old, bringing two opportunities for the mental-health field. First, an opportunity to prevent disability among young people, to enhance their wellbeing and capacity to drive the economy and shoulder the burden of dependent elderly. Young people tend to be physically healthy but are disabled by behavioral problems, emotional problems, substance abuse, and cognitive impairments. These conditions respond to mental-health treatments; psychiatry is well-situated to prevent disabilities among young people. Second, an opportunity to prevent ill health among older people, to reduce the future burden of age-related disability from physical, psychiatric, and neurodegenerative diseases. Here we argue that psychiatry is well-situated to prevent disability among older people too, by doing something it does well: treating young people.

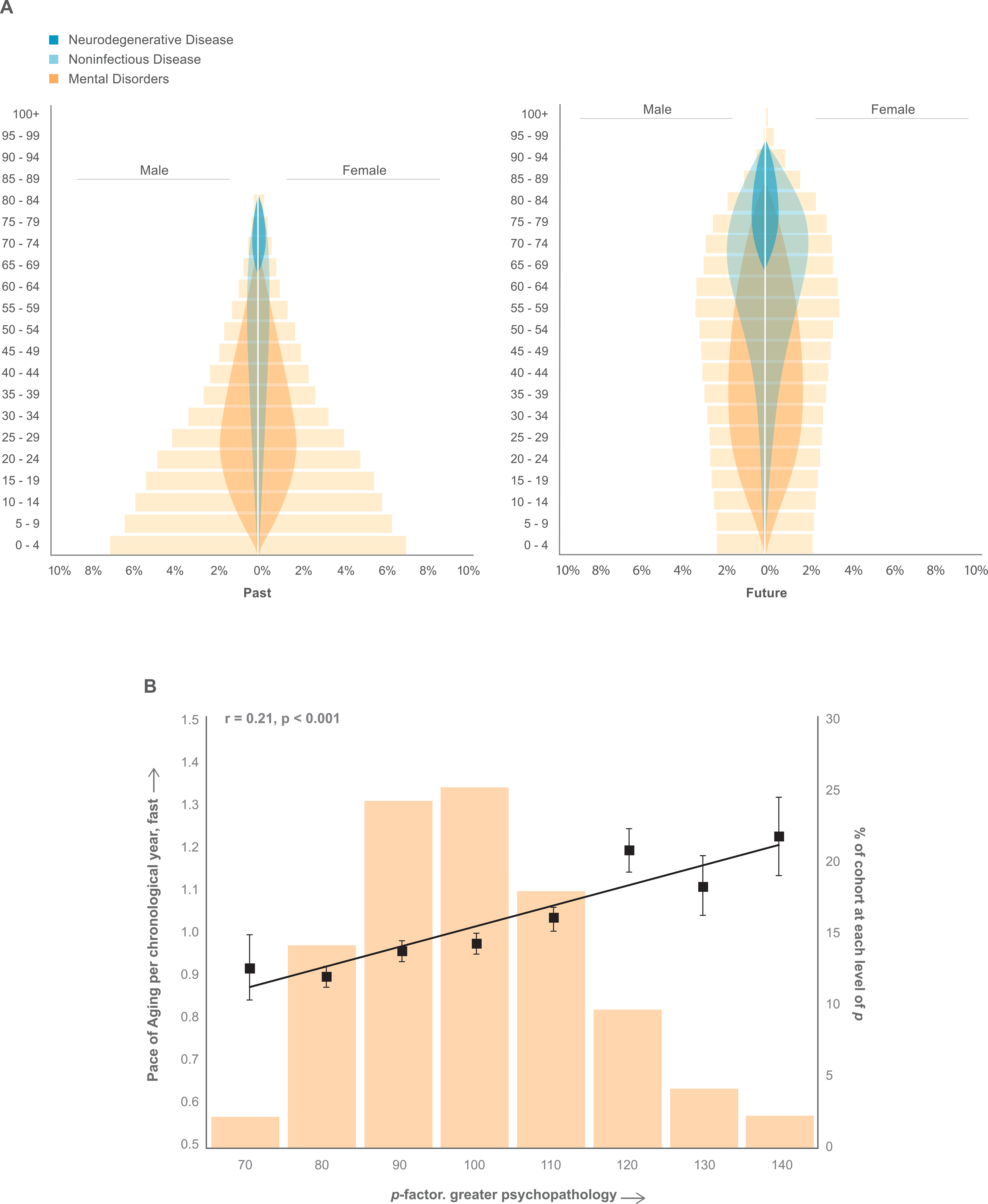

Risk-prediction research shows that the same people who have poor mental and cognitive health while young tend to years later have age-related diseases.1,2 Moreover, the timing is right. Mental-health conditions emerge first, with peak incidence and prevalence in adolescence and young adulthood, whereas non-infectious physical diseases appear in midlife, and neurodegenerative conditions come to attention in late life (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Psychiatry’s Opportunity to Prevent Age-related Disease.

Panel A is a stylized depiction of historical shifts in the distribution of age groups in the population. Age bands sum to 100%. First, compare the chart from the past to the chart for the future, to view the historical shift in the support ratio of young workers versus dependent elders. When the population forms a pyramid, as it did 40 years ago, many young workers support elders. When the population ages, as it will 40 years from now, fewer young workers will support elders (source: https://www.populationpyramid.net). Second, we overlaid the charts with colors to show stylized depictions of age-of-onset and prevalence of mental disorders (orange), non-infectious physical diseases (aqua), and neurodegenerative conditions (blue). Young people who experience mental disorder tend to develop non-infectious and neurodegenerative diseases as they age. Panel B shows that individuals in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study who experience more psychopathology tend to age faster. The p factor operationalizes the theory of liability to experience any and all mental disorders over the life-course. We measured p as a latent factor summarizing the common variance among all of the multiple psychiatric symptoms ever experienced by Dunedin cohort members between ages 18–38 years. The measure p is standardized to a mean of 100 (SD=15), and higher p scores indicate more psychopathology.4 Histogram bars show the percentages of the sample (right vertical-axis) at different levels of the p factor, which is normally distributed as a bell curve. The Pace of Aging operationalizes the coordinated progressive loss of integrity across bodily systems that is the aging process according to geroscience theory.9 We measured the pace of biological aging from changes in 18 biomarkers of Dunedin cohort members’ cardiovascular, metabolic, endocrine, pulmonary, hepatic, renal, immune, and periodontal systems. These 18 biomarkers were measured when cohort members were aged 26, 32, and 38 years. The Pace of Aging quantifies Study members’ rate of biological aging in year-units of physiological decline per chronological year. The squares and standard error bars show the Pace of Aging (left vertical-axis) of individuals as a function of their p scores < 75, 75–85, 85–95, 95–105, 105–115, 115–125, 125–135, and >135. The straight regression line shows the correlation between the p-factor and accelerated Pace of Aging, r=.21, p<.01, calculated on the full distribution of scores in the cohort.

During the first half of the life-course mental disorder affects most of the population.

How we know this.

National-health-system registers show the lifetime prevalence of mental-disorder treatment is 30%. Because many people with disorder are not treated, 30% is a lower bound. Surveys such as NCS-R estimate lifetime prevalence near 50%. Because cross-sectional surveys are biased by recall failure, and individuals with disorders resulting in homelessness, institutionalization, or survey refusal are missed, 50% is an undercount. Several prospective-longitudinal studies that interview participants every few years have observed how disorders accumulate. These studies count cases irrespective of treatment, minimize recall failure, and report lifetime disorder prevalence between 60%−85%, by midlife.3

What it means.

Mental disorder affects almost everyone eventually. For some people, mental disorder is like influenza, kidney stone, or fracture; disabling but short-lived. For others, mental disorder becomes a long-term condition like rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, or COPD. The ubiquity of mental disorder recommends primary prevention that takes a universal approach.

Psychopathology is trans-diagnostic, and predicts accelerated biological aging..

How we know this.

Longitudinal studies show that most people who present with a specific psychiatric disorder also experience other, different, pre-occurring, co-occurring, and future-occurring mental disorders.4 The severity of one’s propensity to develop any and all disorders during the life-course is summarized by one dimension, termed ‘p.’4 The p-factor tops a hierarchy comprising the Internalizing dimension of mood and anxiety symptoms; the Externalizing dimension of substance and antisocial-disruptive symptoms; and the Psychotic Experiences dimension of disorganized thoughts, untrue beliefs, dissociation, and hallucinations. Additionally, p predicts Pace of Aging, a measure of age-related multiple-organ-system decline (Figure 1B).

What it means.

Carriers of a general liability to mental disorder show accelerated biological aging toward late-life disease and early mortality.

Disability and service use are concentrated in a small segment of the population characterized by mental disorder and its risk factors.

How we know this.

National registers reveal that a small segment of the population accounts for the bulk of services used: social-welfare payments; hospital-bed nights, prescription-fills, criminal convictions, and injury-related insurance claims.5 Importantly, high-rate users in one service sector tended to be high-rate users in multiple other sectors. Such individuals could be accurately identified by risk predictors they had as children, particularly elevated p. In the Dunedin cohort, eight in ten high-need/high-cost service-users had psychiatric disorder by age 15.

What it means.

There is a population segment comprising people who as children share risk factors, as young people have diagnose-able mental disorder, and as adults show accelerated aging. This segment accounts for the bulk of disability-related health and social service-use. This finding recommends interventions taking a targeted approach. Interventions that prevent disability in this population segment could yield very large returns on investment.

Mental disorders can be predicted from risk factors in childhood.

How we know this.

Risk factors co-occur in childhood, and prediction of health is strongest when they accumulate. Socioeconomic deprivation, maltreatment, low IQ, poor self-control, and family psychiatric history constitute potent childhood risks for all mental disorders, and consequently, for p, the general liability to develop disorder. These same early-life risks identify high-need/high-cost service-users. Prediction is moderately good beginning at age 3 years, and risk is compounded by harmful experiences during adolescence.6

What it means.

Early-years interventions are effective but yield incomplete prevention of mental-health problems. This recommends both primary prevention to mitigate risk factors and secondary prevention to treat behavioral, emotional, and cognitive disorders.

A research and practice agenda from risk-factor research.

Psychiatry has an opportunity to re-envision its prevention goals. Treating disorders and reducing their risk factors benefits the young, but it could also have the knock-on effect of reducing disease and health-service and social-service use in the same people when they reach later life. Preventive psychiatry can enhance the carrying capacity of young people so the burden of dependent elders will sit more lightly on their young shoulders, but can also lighten the weight of disability among future older adults. Testable hypotheses suggest themselves: Causal risks affecting children are trans-diagnostic, implying early-years primary prevention may diminish general liability toward disorder. Emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and substance problems are ubiquitous; implying that anti-stigma public-awareness programs and enhancing young people’s treatment access might benefit late-life health. Readily accessible trans-diagnostic psychotherapy could work as first-line treatment.8 Efforts to expand mental-health treatment accessibility are promising7; the hypothesis of long-term health benefit needs more research. Targeted interventions may interrupt the path from a youth’s first disorder to becoming a high-need/high-cost public-service user in later life. Testing these ideas requires abandoning conventional boundaries: sick versus well, diagnosis X versus Y, mental versus physical illness, and vitally, young versus old. Disease prevention invites seeing each patient as a member of the population, with a life behind them, and a life ahead.

Funding/Support:

Supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG032282, AG049789), National Institute of Child Health and Development (HD077482), U.K. Medical Research Council (P005918, G1002190), the Jacobs Foundation, and the Avielle Foundation.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

Funder had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Both authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Originality of Content: All information and materials in the manuscript are original.

Item10 is: https://www.populationpyramid.net

References:

- 1.Scott KM, Lim C, Al Hamzawi A, Alonson J, et al. Association of Mental Disorders with Subsequent Chronic Physical Conditions: World Mental Health Surveys From 17 Countries. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73;150–158. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence D, Hancock KJ, Kisely S The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers. British Medical Journal 2013; 346, f2539. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.f2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaefer JD, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Houts R, Horwood J, Hussong A, Ramrakha S, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Enduring mental health: Prevalence and prediction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2017; 126; 212–224. DOI: 10.1037/abn0000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspi A & Moffitt TE. All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry 2018: 175, 831–844. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Harrington HL, Hogan S, Ramrakha S. Poulton R, Moffitt TE. A small segment of the population with large economic burden: Childhood forecasting. Nature Human Behaviour 2017: 1; 0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington HL, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts B, Ross S, Sears M, Thomson M, Caspi A A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011:108; 2693–2698. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark DM Realizing the mass public benefit of evidence-based psychological therapies: The IAPT program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2018: 14; 159–183. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier MA, Meier MH. Clinical implications of a general psychopathology factor: a cognitive-behavioral transdiagnostic group treatment for community mental health. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2018. DOI: 10.1037/int0000095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belsky DW, Caspi A, Houts R, Cohen H, Corcoran DL, Danese A, Harrington HL, Israel S, Levine ME, Schaefer J, Sugden K, Williams B, Yashin AI, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015: 112; 4104–4110. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1506264112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]