Abstract

Background:

Treatment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) has become increasingly dominated by endovascular interventions. The short-term outcomes of endovascular therapy have been well-studied but late outcomes remain largely unpublished; in this series we report the late outcomes of primary nitinol stenting.

Methods:

All patients undergoing primary nitinol stenting of the superficial femoral artery (SFA) and/or popliteal artery (PA) during a 10-year period by a single surgeon (S.K.) were reviewed. No attempts were made on patients with orificial or total occlusion of the SFA, PA, and proximal tibial arteries. Differences in primary patency, primary-assisted patency, secondary patency, and freedom from bypass were evaluated at one, five, and nine years.

Results:

A total of 294 limbs in 240 patients were treated. 130 additional endovascular procedures were observed during the study period averaging to 0.16 endovascular interventions per limb per year. Primary patency in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 79%, 35%, and 19% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 62%, 11%, and 3% respectively. Secondary patency in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 96%, 81%, and 65% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 92%, 64%, and 41% respectively. Freedom from bypass in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 98%, 89%, and 85% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 95%, 78%, and 69% respectively. Five below the knee amputations were observed during the study period.

Conclusions:

An endovascular first approach can be applied to the vast majority of femoropopliteal lesions. While the late outcomes of TASC C/D lesions are inferior to those of TASC A/B lesions, an endovascular first approach still provides durable outcomes.

Introduction:

The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) continues to rise as life-expectancies increase. During the first decade of the twenty-first century, it is estimated that the prevalence of peripheral arterial disease has risen 29% in low-income and middle-income countries, and 13% in high-income countries.1 Recent meta-analysis has also demonstrated that the life-expectancy of patients with peripheral arterial disease has either increased or is greater than previously estimated with a 5-year cumulative mortality of 27% for patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease.2 Thus while significant advancement have been made in the medical treatments of atherosclerotic disease, and by extension peripheral arterial disease, the need for effective, durable interventions for peripheral arterial disease is greater than ever.

When peripheral angioplasty was first introduced in 1964, it viewed with great skepticism. Now, nearly fifty years later, endovascular therapy has become ubiquitous in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease and many centers use it as first-line therapy, reserving open surgery for its failures.3 As the number of patients treated by endovascular therapy continues to grow, significant questions remain regarding its long-term efficacy.

While the short and medium-term efficacy of endovascular therapy for PAD is well supported by a large number of publications, data is sparse regarding its long-term efficacy. It is the purpose of this study was to elucidate the long-term efficacy of nitinol stenting for femoropopliteal atherosclerotic disease over a time span of ten years.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained. All patients undergoing primary nitinol stenting of the superficial femoral artery (SFA) and/or popliteal artery (PA) from January 2004 until January 2014 by a single surgeon were reviewed. Patients were considered for revascularization if they had non-invasive vascular studies confirming peripheral arterial disease and either critical limb ischemia, defined as tissue loss or rest pain, or lifestyle-limiting claudication refractory to best-medical management and walking therapy. Our algorithm for revascularization begins with an angiogram. All limbs, except for those with orificial occlusion of the SFA or a continuous occlusion of the SFA, PA, and proximal tibial arteries, underwent an attempt at endovascular revascularization. Endovascular revascularization attempts of the SFA and/or popliteal artery were performed exclusively with self-expanding, bare-metal, laser-cut nitinol stents manufactured by either Abbot laboratories (Chicago, Illinois) or Medtronic plc (Fridley, Minnesota). No attempts were made to treat disease of the native SFA or popliteal artery with atherectomy, drug-coated balloons, angioplasty without stenting, woven stents, or covered stents. Following endovascular revascularization, all patients were placed on a 30-day regimen of 75mg of clopidogrel and 81mg of aspirin daily followed by indefinite therapy with 81mg of aspirin daily. Patients who had not been receiving clopidogrel preoperatively received a 300mg loading dose following the intervention. Patient and limb-specific characteristics were collected including demographics, comorbidities, indication for procedure, lesion location, and lesion TASC II score. Patients underwent arterial duplex ultrasound 6 weeks after the procedure and at 6-month intervals thereafter. Patients who discontinued vascular surgery follow-up but continued to present to our hospital system had their charts reviewed to determine if they had undergone additional duplexes, interventions, or amputations. This extended clinical follow-up was dependent on unassociated providers. Thirty-day major adverse cardiac events, defined as stroke or myocardial infarction, and 30-day major adverse limb events, defined as unplanned reoperation or limb loss, were recorded.

Primary patency, primary assisted patency, secondary patency, freedom from bypass, and freedom from amputation were recorded. Primary patency was defined as the time to development of a hemodynamically significant stenosis, defined as a peak systolic velocity of at least 200 cm/s and a 3:1 velocity ratio across the lesion. Primary assisted patency was defined as time to reintervention to maintain patency. Secondary patency was defined as time to stent occlusion. Freedom from bypass was defined as time to surgical bypass of the lesion. Freedom from amputation was defined as the time to amputation of the target limb at the level of the ankle or higher.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the relationship between TASC group, indication, or lesion location and 10-year clinical outcomes. A robust sandwich covariance matrix approach was used to adjust for the clustered data of limbs within patients contributing more than one stented limb. The proportional hazards assumption was verified by checking the model cumulative martingale residuals and the Kolmogorov-type supremum test. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to visualize unadjusted survival rates for 10 years and notations were made where standard error exceeded 10 percent. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, a total of 359 angiograms were performed and 294 (82%) involved endovascular treatment of the femoropopliteal region. A total of 294 femoropopliteal interventions were performed on 240 patients (Table I–II.) The mean age was 76, thirty-three percent of patients had TASC C/D lesions, and forty percent of interventions were performed for critical limb ischemia. Mean ultrasonographic follow-up was 23 months (SD, 30 months) and mean physical exam follow up was 40 months (SD, 41 months.) Two patients experienced major adverse cardiac event (MACE) within 30 days, both non-fatal NSTEMIs. No patients experienced major adverse limb events (MALE) within 30 days.

Table I.

Demographics and limb characteristics

| Variable | Per Limb | Per Patient |

|---|---|---|

| n = 294 | n = 240 | |

| Age, Mean ± SD | 76 ± 11 | 76 ± 11 |

| Female, n, (%) | 162 (55) | 131 (55) |

| Race | ||

| White, n, (%) | 189 (64) | 151 (63) |

| Hispanic, n, (%) | 32 (11) | 28 (12) |

| African American, n, (%) | 63 (21) | 54 (23) |

| Asian, n, (%) | 10 (3) | 7 (3) |

| History of Smoking, n, (%) | 116 (39) | 101 (42) |

| Hypertension, n, (%) | 265 (90) | 214 (89) |

| Prior CABG, n, (%) | 42 (14) | 32 (13) |

| COPD, n, (%) | 48 (16) | 38 (16) |

| History of CVA, n, (%) | 22 (7) | 20 (8) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n, (%) | 150 (51) | 128 (53) |

| History of MI, n, (%) | 33 (11) | 19 (8) |

| Coronary Artery Disease, n, (%) | 131 (45) | 102 (43) |

| Diabetes, n, (%) | 137 (47) | 116 (48) |

| CHF, n, (%) | 38 (13) | 36 (15) |

| CKD, n, (%) | 42 (14) | 37 (15) |

| HD Dependent, n, (%) | 11 (4) | 10 (4) |

| CLI (Indication), n, (%) | 118 (40) | |

| Left Sided Lesion, n, (%) | 154 (52) | |

| Lesion Location | ||

| Femoral, n, (%) | 159 (54) | |

| Popliteal, n, (%) | 51 (17) | |

| Femoropopliteal, n, (%) | 84 (29) | |

| TASC II Classification | ||

| TASC A, n, (%) | 64 (22) | |

| TASC B, n, (%) | 135 (46) | |

| TASC C, n, (%) | 61 (21) | |

| TASC D, n, (%) | 34 (12) | |

| Ultrasound Follow-Up, months, median (IQR) | 11 (4–26) | |

| Physical exam Follow-up, months, median (IQR) | 34 (6–79) |

Table II.

Expanded limb characteristics. Percentages refer to the percent of patients within each indication that make up a particular TASC II classification.

| TASC II Classification | CLI, n = 118 | Claudication, n = 176 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue loss, n = 70 | Rest pain, n = 48 | ||

| TASC A/B, n = 199 | 42 (60%) | 30 (62.5%) | 127 (72%) |

| TASC C/D, n = 95 | 28 (40%) | 18 (37.5%) | 49 (28%) |

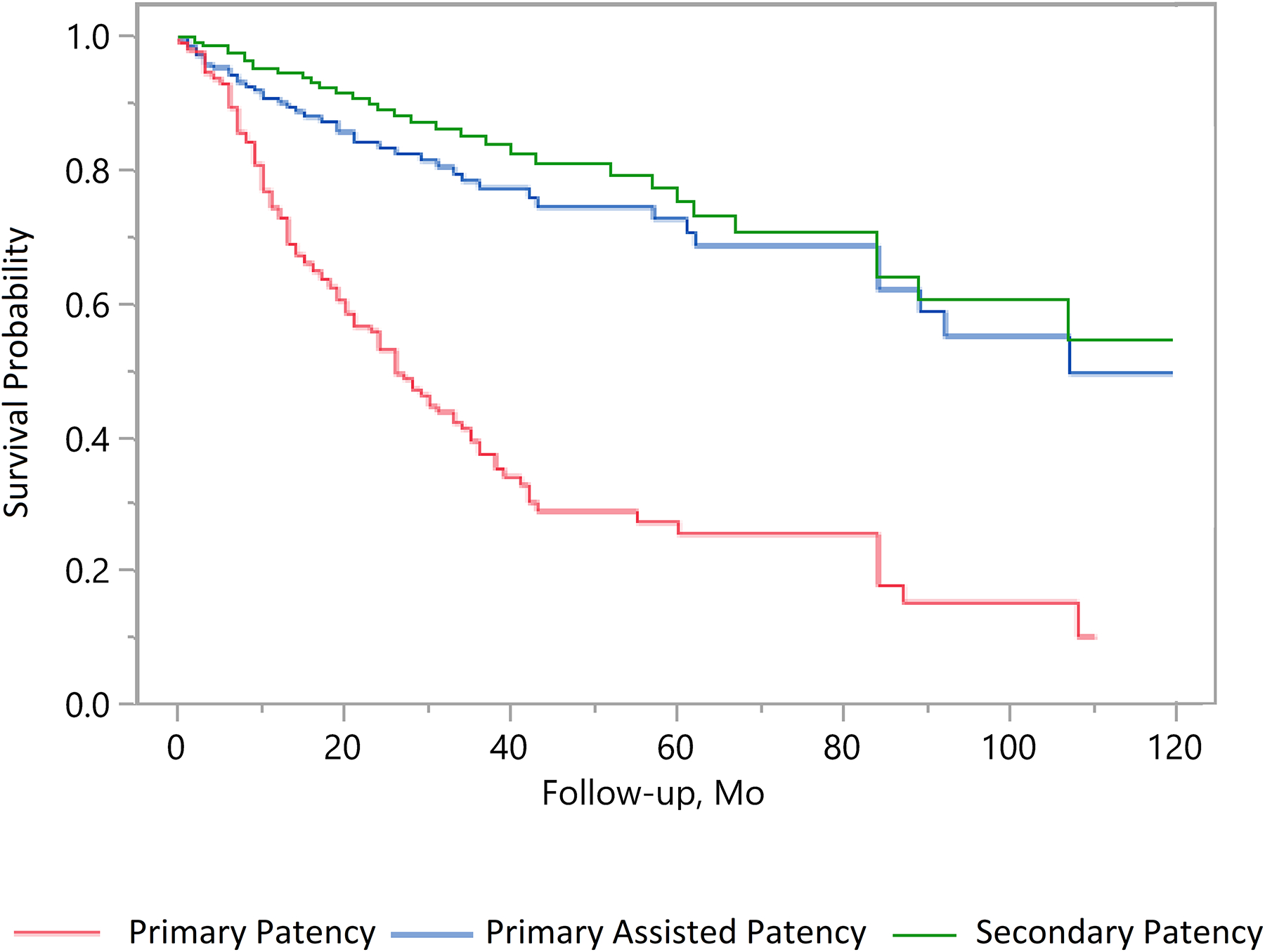

The 294 limbs had a cumulative secondary patency of 6978 months and during this period an additional 73 interventions were performed to assess or maintain patency resulting in an average of one additional intervention per lesion every 8 years (Figure 1.) Unadjusted patency rates and patency rates adjusted for patients contributing more than one limb were within 2% of each other during years one and five, at year nine some values diverged by up to 10% (Table III.)

Figure 1.

Unadjusted primary patency, primary-assisted, and secondary patency survival probabilities.

Table III.

1-year, 5-year, and 9-year adjusted survival probabilities

| Outcome | 1-year | 5-year | 9-year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASC AB | TASC CD | TASC AB | TASC CD | TASC AB | TASC CD | |

| Primary patency | 0.79(0.03) | 0.62(0.05) | 0.35(0.05) | 0.11(0.04) | 0.19(0.07) | 0.03(0.03)† |

| Primary assisted patency | 0.93(0.02) | 0.84(0.04) | 0.81(0.04) | 0.57(0.08) | 0.64(0.08)† | 0.32(0.10)† |

| Secondary patency | 0.96(0.01) | 0.92(0.03) | 0.81(0.05) | 0.64(0.08) | 0.65(0.08) | 0.41(0.11)† |

| Freedom from bypass | 0.98(0.01) | 0.95(0.02) | 0.89(0.03) | 0.78(0.06) | 0.85(0.04) | 0.69(0.08) |

| Freedom from amputation | 0.99(0.01) | 0.99(0.01) | 0.98(0.01) | 0.97(0.02) | 0.96(0.02) | 0.94(0.04) |

Kaplan-Meier survival probability estimates (SE) are reported. The difference between the unadjusted and adjusted survival probabilities is 2% or less unless denoted by dagger (†) in which case it 10% or less.

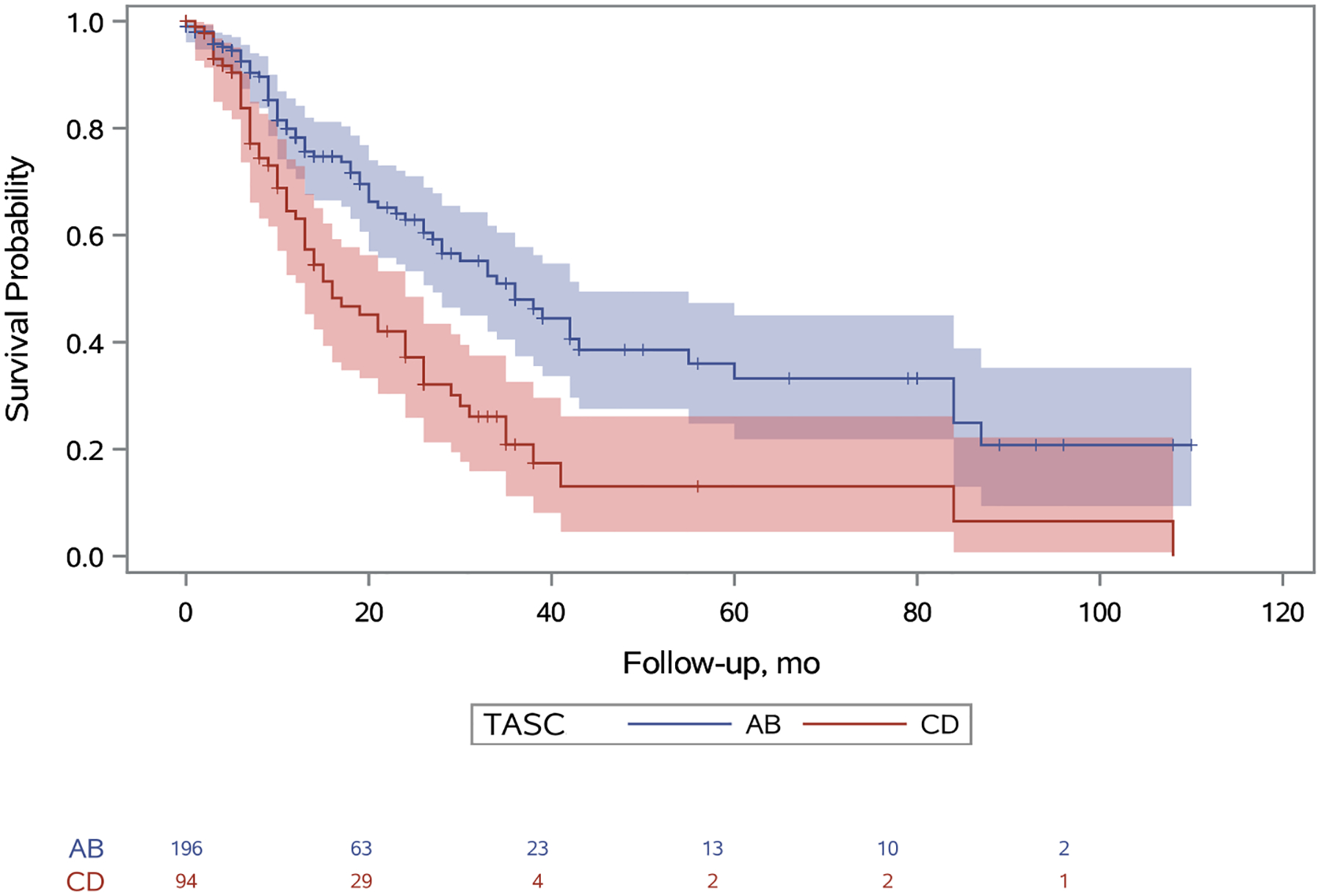

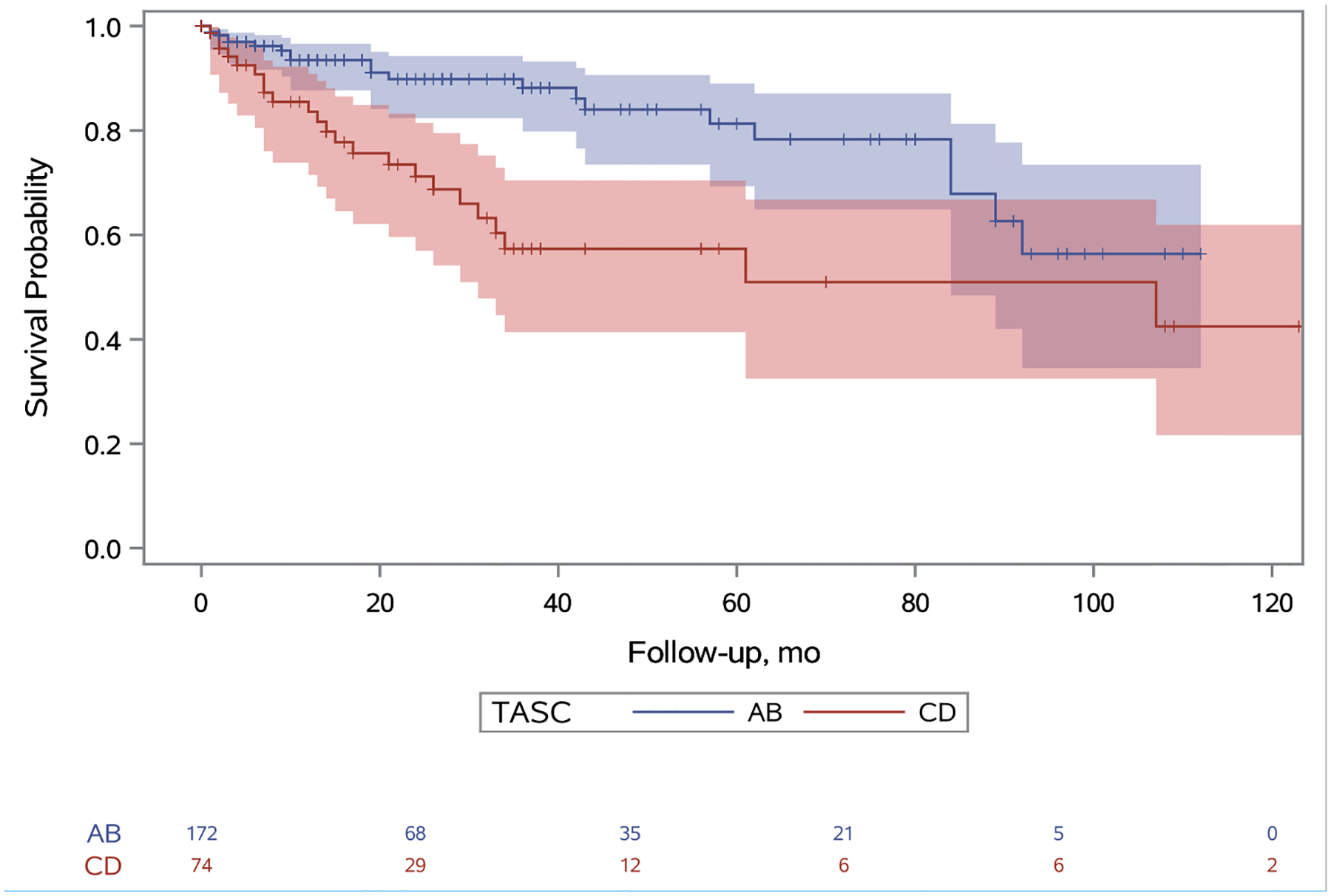

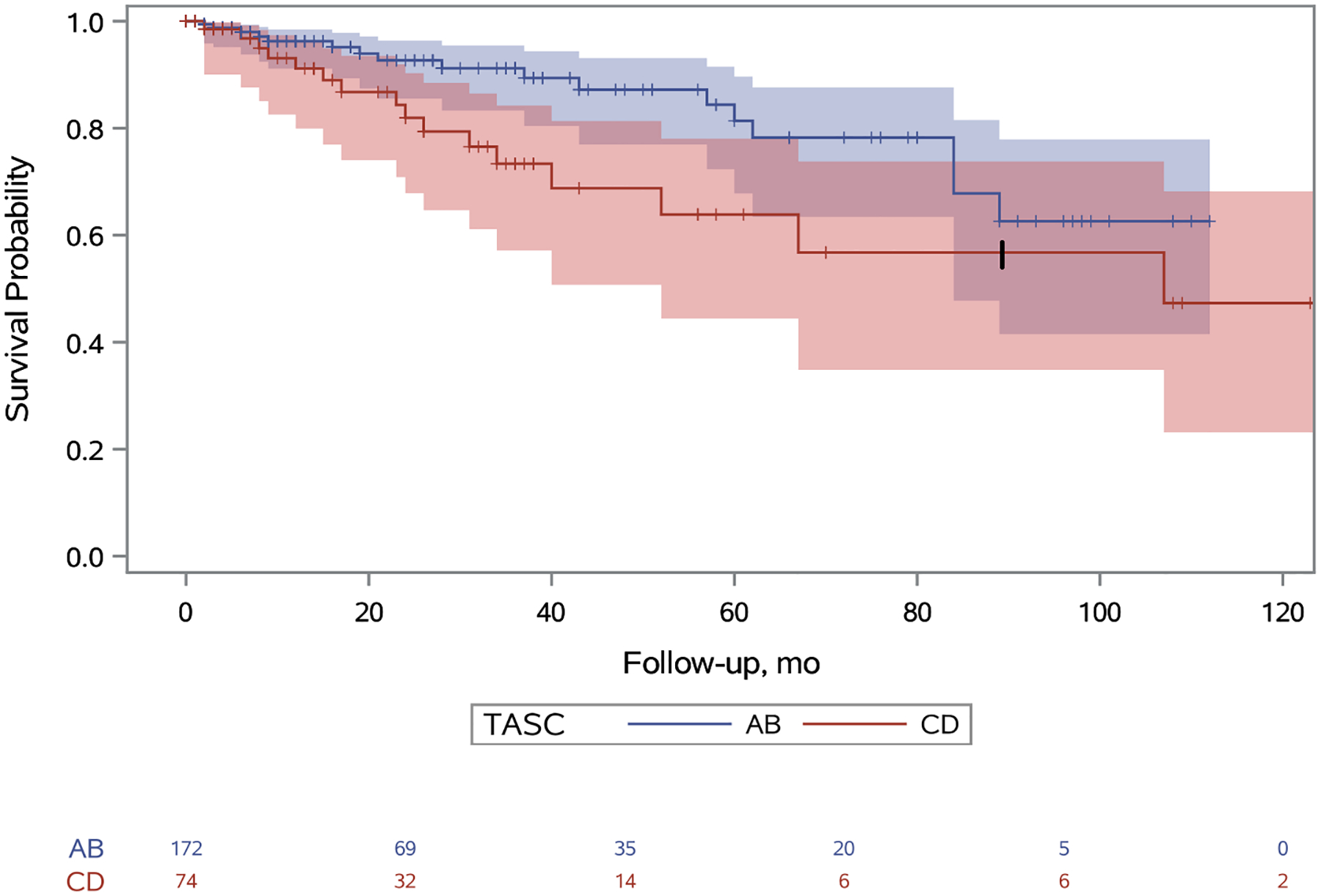

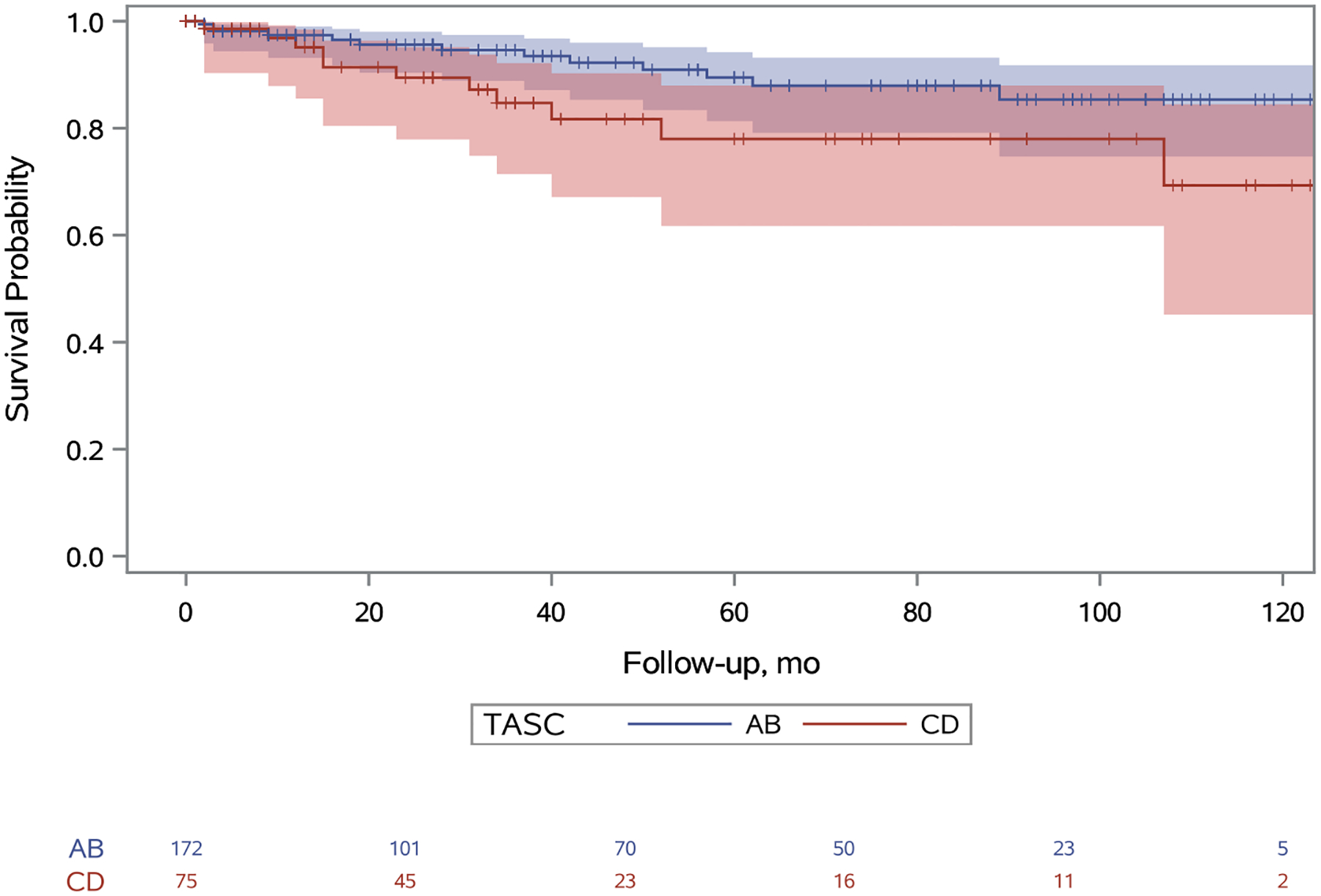

Primary patency in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 79%, 35%, and 19% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 62%, 11%, and 3% respectively (Figure 2; hazard ratio [HR], 2.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.44–2.98). Primary assisted patency in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 93%, 81%, and 64% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 84%, 57%, and 32% respectively (Figure 3; HR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.39–4.74). Secondary patency in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 96%, 81%, and 65% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 92%, 64%, and 41% respectively (Figure 4; HR, 2.09; 95% CI: 1.04–4.20). Freedom from bypass in TASC A/B limbs at one, five, and nine years was 98%, 89%, and 85% respectively and in TASC C/D limbs was 95%, 78%, and 69% respectively (Figure 5; HR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.04–4.83). The hazards of primary patency failure, primary assisted patency failure, secondary patency failure, and bypass were all higher for limbs with critical limb ischemia or SFA lesions, but these hazards did not reach statistical significance (Table IV). A total of five major amputations were observed during the study period and freedom from amputation never reached statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted primary patency survival probabilities for TASC A/B and TASC C/D limbs. A 95% confidence limit is shaded. The number of limbs at risk is listed at the bottom. Censored patients are designated with a tick. Standard error does not exceed 10% at any point. The hazard of primary patency failure for patients with TASC score CD is 2.07 (95% CI: 1.44–2.98) times the hazard of patients with TASC score AB (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted primary assisted patency survival probabilities for TASC A/B and TASC C/D limbs. A 95% confidence limit is shaded. The number of limbs at risk is listed at the bottom. Censored patients are designated with a tick. Standard error does not exceed 10% at any point. The hazard of primary assisted patency failure for patients with TASC score CD is 2.57 (95% CI: 1.39–4.74) times the hazard of patients with TASC score AB (p=0.0013).

Figure 4.

Unadjusted secondary patency survival probabilities for TASC A/B and TASC C/D limbs. A 95% confidence limit is shaded. The number of limbs at risk is listed at the bottom. Censored patients are designated with a tick. Standard error for the TASC C/D limbs exceeds 10% at 84 months and this is denoted with a thick tick mark. The hazard of bypass for patients with TASC score CD is 2.09 (95% CI: 1.04–4.20) times the hazard of patients with TASC score AB (p=0.04).

Figure 5.

Unadjusted freedom from bypass survival probabilities for TASC A/B and TASC C/D limbs. A 95% confidence limit is shaded. The number of limbs at risk is listed at the bottom. Censored patients are designated with a tick. Standard error does not exceed 10% at any point. The hazard of bypass for patients with TASC score CD is 2.24 (95% CI: 1.04–4.83) times the hazard of patients with TASC score AB (p=0.04).

Table IV.

Hazard ratios are displayed for the length of the study. Critical Limb Ischemia (CLI). SFA (Superficial Femoral Artery).

| Comparison | Primary patency | Primary assisted patency | Secondary patency | Freedom from bypass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASC C/D (vs TASC A/B) | 2.07 (1.44–2.98) | 2.57 (1.39–4.74) | 2.09 (1.04–4.20) | 2.24 (1.035–4.83) |

| CLI (vs claudication) | 1.34 (0.89–2.01) | 1.36 (0.72–2.54) | 1.71 (0.86–3.43) | 1.15 (0.51–2.60) |

| SFA lesion (vs popliteal)* | 1.25 (0.68–2.27) | 1.64 (0.57–4.76) | 1.10 (0.37–3.23) | 1.41 (0.40–4.98) |

84 of the 294 limbs were classified as having combined SFA and popliteal lesions and were excluded from this analysis.

Discussion

The frequency with which peripheral arterial disease is treated percutaneously grows at a rapid rate. From 2003 to 2011, the percentage of patients admitted with critical limb ischemia who were treated with endovascular therapy grew from 5% to 11% while the percentage of patients treated surgically decreased from 14% to 9%.4 Retrospective observational studies have demonstrated durable medium-term results in TASC C/D patients treated with endovascular therapy. Dosluoglu et al. compared 149 patients with TASC D lesions who had undergone surgery with 190 patients who had undergone endovascular therapy and found similar patency rates at 5 year.5 At five years, the endovascular group had a primary patency of 39%, an assisted primary patency of 55%, and a secondary patency of 60%. Lida et al., followed 423 patients with TASC C/D lesions and at 5 years found a primary patency of 55%.6 Finally, Soga et al., followed 290 patients with TASC C/D lesions and at 5 years found a primary patency of 54% and a secondary patency of 76%.7

Our study is a single-surgeon, retrospective observational study examining patients who had undergone primary nitinol stenting for femoropopliteal disease. The use of a single surgeon at a single institution limits the generalizability of the study and retrospective observational studies are not as reliable as standardized prospective studies. In comparison to the above cited studies, we had a lower primary patency rate but comparable secondary patency rates. Innumerable differences exist among these retrospective observational studies which may explain the variance in primary patency, the most notable being our aggressive endovascular first policy. Neither Lida or Soga utilized an endovascular first policy and Dosluoglu’s endovascular first policy assigned only 71% of patients to endovascular therapy and the remaining 29% to open surgery.

In this study, endovascular therapy was limited to self-expanding, bare-metal, laser-cut nitinol stents. Although other endovascular therapies are available that warrant consideration, at this time there is not enough evidence to say that they would have significantly improved our outcomes. The VIASTAR and VIBRANT studies provided level 1b evidence supporting the use of covered stents but the benefits in native disease were subtle and will require additional research before gaining widespread adoption.8,9 Flexible nitinol stents could have an advantage in flexible regions such as the behind-the-knee popliteal artery, but randomized controlled trials have failed to demonstrate superiority to laser-cut nitinol stents.10 There is evidence that angioplasty without stenting may provide equivocal results for femoropopliteal lesions, especially in shorter lesions.11,12 Drug-eluting balloons and stents have evidence that they increase patency, but concerns about the increase in all-cause mortality warrant additional investigation prior to the routine incorporation of them into clinical practice.13 Finally, atherectomy lacks high-quality studies to support its use over balloon angioplasty.14

While some surgeons express concern that an endovascular first approach may undermine future surgical revascularization, observational studies have shown that such instances are rare. In a set of 239 limbs that had undergone primary femoropopliteal stenting, Gur and authors identified ten patients who subsequently underwent open bypass for stent failure and noted that in only two cases patients had significant disease progression that negatively impacted the subsequent bypass.15

Studies examining the long-term patency of autogenous vein bypass for femoropopliteal disease have demonstrated that although the patency rate is high, the interval patency does not improve with time. In an analysis of 2058 in situ saphenous vein bypasses, Shah and authors demonstrated a primary patency of 84% at 1 year, 72% at 5 years, and 55% at 10 years and a secondary patency of 91% at 1 year, 81% at 5 years, and 70% at 10 years.16 Despite these impressive patency rates, the primary and secondary interval patency rates did not change over time implying that bypasses do not become more durable with time contrary to what is often thought.

More importantly, however, will be to know when an endovascular first policy can provide superior outcomes to surgical bypass. Although prior randomized controlled trials have failed to definitively answer this question, the BEST-CLI trial is nearing completion and is an opportunity to define the circumstances under which endovascular therapy or surgical bypass is most appropriate.17

Although this study demonstrates that TASC C/D lesions have inferior outcomes compared to TASC A/B lesions, the differences in secondary patency and freedom from bypass were small throughout the long follow-up period. Therefore, we believe it is reasonable to offer patients with technically amenable TASC C/D lesions endovascular therapy first.

Acknowledgements:

Statistical analysis was provided by the Southern California Clinical and Translation Science Institute (SC CTSI). Consideration was paid for this third-party statistical analysis from our institution’s internal funds. Their work is supported by grants UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, Norman PE, Sampson UK, Williams LJ, Mensah GA, Criqui MH. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. The Lancet. 2013. Oct 19;382(9901):1329–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sigvant B, Lundin F, Wahlberg E. The risk of disease progression in peripheral arterial disease is higher than expected: a meta-analysis of mortality and disease progression in peripheral arterial disease. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2016. Mar 1;51(3):395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisdas T, Borowski M, Torsello G, Adili F, Balzer K, Betz T, Billing A, Böckler D, Brixner D, Debus SE, Donas KP. Current practice of first-line treatment strategies in patients with critical limb ischemia. Journal of vascular surgery. 2015. Oct 1;62(4):965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal S, Sud K, Shishehbor MH. Nationwide trends of hospital admission and outcomes among critical limb ischemia patients: from 2003–2011. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016. Apr 26;67(16):1901–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dosluoglu HH, Lall P, Harris LM, Dryjski ML. Long-term limb salvage and survival after endovascular and open revascularization for critical limb ischemia after adoption of endovascular-first approach by vascular surgeons. Journal of vascular surgery. 2012. Aug 1;56(2):361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iida O, Soga Y, Hirano K, Suzuki K, Yokoi H, Nobuyoshi M, Muramatsu T, Inoue N, Nanto S, Uematsu M. Long-term outcomes and risk stratification of patency following nitinol stenting in the femoropopliteal segment: retrospective multicenter analysis. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. 2011. Dec;18(6):753–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soga Y, Iida O, Hirano K, Yokoi H, Nanto S, Nobuyoshi M. Mid-term clinical outcome and predictors of vessel patency after femoropopliteal stenting with self-expandable nitinol stent. Journal of vascular surgery. 2010. Sep 1;52(3):608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lammer J, Zeller T, Hausegger KA, Schaefer PJ, Gschwendtner M, Mueller-Huelsbeck S, Rand T, Funovics M, Wolf F, Rastan A, Gschwandtner M. Heparin-bonded covered stents versus bare-metal stents for complex femoropopliteal artery lesions: the randomized VIASTAR trial (Viabahn endoprosthesis with PROPATEN bioactive surface [VIA] versus bare nitinol stent in the treatment of long lesions in superficial femoral artery occlusive disease). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013. Oct 8;62(15):1320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geraghty PJ, Mewissen MW, Jaff MR, Ansel GM, VIBRANT Investigators. Three-year results of the VIBRANT trial of VIABAHN endoprosthesis versus bare nitinol stent implantation for complex superficial femoral artery occlusive disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2013. Aug 1;58(2):386–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laird JR, Zeller T, Loewe C, Chamberlin J, Begg R, Schneider PA, Nanjundappa A, Bunch F, Schultz S, Harlin S, Lansky A. Novel nitinol stent for lesions up to 24 cm in the superficial femoral and proximal popliteal arteries: 24-month results from the TIGRIS randomized trial. Journal of Endovascular Therapy. 2018. Feb;25(1):68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu CC, Kwan GN, Singh D, Rophael JA, Anthony C, van Driel ML. Angioplasty versus stenting for infrapopliteal arterial lesions in chronic limb‐threatening ischaemia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krankenberg H Schlüter M, Steinkamp HJ, Bürgelin K, Scheinert D, Schulte KL et al. Nitinol stent implantation versus percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in superficial femoral artery lesions up to 10 cm in length: the femoral artery stenting trial (FAST). Circulation. 2007;116:285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Kitrou P, Krokidis M, Karnabatidis D. Risk of death following application of paclitaxel‐coated balloons and stents in the femoropopliteal artery of the leg: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018. Dec 18;7(24):e011245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambler GK, Radwan R, Hayes PD, Twine CP. Atherectomy for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gur I, Lee W, Akopian G, Rowe VL, Weaver FA, Katz SG. Clinical outcomes and implications of failed infrainguinal endovascular stents. Journal of vascular surgery. 2011. Mar 1;53(3):658–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah DM, Darling RC 3rd, Chang BB, Fitzgerald KM, Paty PS, Leather RP. Long-term results of in situ saphenous vein bypass. Analysis of 2058 cases. Annals of surgery. 1995. Oct;222(4):438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farber A, Rosenfield K, Siami FS, Strong M, Menard M. The BEST-CLI trial is nearing the finish line and promises to be worth the wait. Journal of vascular surgery. 2019. Feb 1;69(2):470–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]