Abstract

Background:

The clinical manifestation of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is causally linked to the inflammatory microenvironment and proliferation of epithelial and stromal cells in the prostate transitional zone. The CXC-chemokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) contributes to inflammation. We evaluated the expression of inflammatory cytokines in clinical specimens, primary cultures, and prostatic lineage cell lines. We investigated whether IL-8 via its receptor system (IL-8 axis) promotes BPH.

Methods:

The messenger RNA and protein expression of chemokines, including components of the IL-8 axis, were measured in normal prostate (NP; n = 7) and BPH (n = 21), urine (n = 24) specimens, primary cultures, prostatic lineage epithelial cell lines (NHPrE1, BHPrE1, BPH-1), and normal prostate cells (RWPE-1). The functional role of the IL-8 axis in prostate epithelial cell growth was evaluated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. The effect of a combination with two natural compounds, oleanolic acid (OA) and ursolic acid (UA), was evaluated on the expression of the IL-8 axis and epithelial cell growth.

Results:

Among the 19 inflammatory chemokines and chemokine receptors we analyzed, levels of IL-8 and its receptors (CXCR1, CXCR2), as well as, of CXCR7, a receptor for CXCL12, were 5- to 25-fold elevated in BPH tissues when compared to NP tissues (P ≤ .001). Urinary IL-8 levels were threefold to sixfold elevated in BPH patients, but not in asymptomatic males and females with lower urinary tract symptoms (P ≤ .004). The expression of the IL-8 axis components was confined to the prostate luminal epithelial cells in both normal and BPH tissues. However, these components were elevated in BPH-1 and primary explant cultures as compared to RWPE-1, NHPrE1, and BHPrE1 cells. Knockout of CXCR7 reduced IL-8, and CXCR1 expression by 4- to 10-fold and caused greater than or equal to 50% growth inhibition in BPH-1 cells. Low-dose OA + UA combination synergistically inhibited the growth of BPH-1 and BPH primary cultures. In the combination, the drug reduction indices for UA and OA were 16.4 and 7852, respectively, demonstrating that the combination was effective in inhibiting BPH-1 growth at significantly reduced doses of UA or OA alone.

Conclusion:

The IL-8 axis is a promotor of BPH pathogenesis. Low-dose OA + UA combination inhibits BPH cell growth by inducing autophagy and reducing IL-8 axis expression in BPH-epithelial cells.

Keywords: chemokines, CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR7, inflammation, prostate proliferation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

An estimated 210 million men suffer from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) globally, and this number will increase as more men are projected to live longer in the coming years.1 The transitional zone of the human prostate is where BPH develops. The transitional zone surrounds the urethra and is a small glandular region that makes up only 5% of the prostate volume in young adults.2 In BPH, nodular expansion of this zone results in bladder outlet obstruction leading to an impediment to urine flow.3–5 The primary risk factor for BPH is aging. However, men as young as 40 may be diagnosed with BPH.3–7 The average weight of the prostate in men with BPH, analyzed at autopsy, is 33 ± 16 g.7,8 Studies using serial prostate volume measurements show that from 31 to 50 years of age, when prostate volume doubles every 4.5 years, the rate of weight doubling slows to 10 years in men 51 to 70 years of age.8 Therefore, it appears that the critical period to prevent BPH is in men less than or equal to 50 years of age when the prostate growth rate is high. Obesity contributing to the chronic inflammatory processes in the prostate gland, and infection are the common etiologies for BPH.5,9,10 The most common clinical manifestation of BPH is the lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). BPH-related LUTS (BPH/LUTS) is defined as storage (irritative) symptoms (daytime urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia), and voiding (obstructive) symptoms (straining, weak stream, intermittent stream, and incomplete emptying). However, other conditions may also cause LUTS in both men and women.3–7,11,12

Chemokines and cytokines are the main drivers of the inflammatory response associated with BPH.9–11,13–15 Chronic inflammation of the prostate is locally induced by chronic prostatitis or as a result of systemic inflammation caused by obesity or associated syndrome X conditions.14 Certain pro-inflammatory factors, including cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-17, are elevated in the circulation and urine of BPH/patients presenting with LUTS.13,15,16 Cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8, are functionally linked to cancer, including prostate cancer.17–20 However, it is not well-established whether increased inflammatory signaling contributes to the development and progression of BPH or is a consequence of BPH pathophysiology.

We hypothesized that pro-inflammatory cytokines promote epithelial proliferation within the prostatic transitional zone and potential targets for the management of BPH. We tested this hypothesis by examining the expression of inflammatory cytokines and their receptors in prostate specimens. We also evaluated the functional involvement of IL-8, IL-8 receptors—CXCR1 (R1), CXCR2 (R2), and a CXCL12 receptor, CXCR7 (R7), in established BPH lineage cell lines and primary transitional zone epithelial explant cultures from BPH specimens. In this study, the IL-8 axis is defined as IL-8, R1, R2, and R7. Our data demonstrate an elevation of the IL-8 axis members in BPH tissues, and urine specimens when compared to normal prostate tissues, urine specimens from men without symptomatic BPH, and female patients presenting with LUTS.

Oleanolic acid (OA) and ursolic acid (UA) are isomeric pentacyclic triterpenoid phytochemicals present in various plants.21–28 Both OA and UA show anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, hypolipidemic, antidiabetic, anti-atherosclerotic, and anti-hypertensive effects.29–31 Most studies have tested the effects of OA and UA on a variety of cell models at high doses (20-438 μM).29–34 In xenograft models, UA has shown anticancer, antidiabetic, and antiobesity activities at 150 to 500 mg/kg/d.30,35–39 Administration of UA in the solid diet (1% w/w) for up to 36 weeks did not show systemic toxicity and achieved a serum level of greater than or equal to 3 μM.26 In limited human studies, both OA and UA have shown tolerable toxicity profiles at an oral dose of 0.45 to 3 g once daily for up to 8 weeks.29–31,36,38–45 However, few have reported on the efficacy of a low-dose combination of OA and UA. Due to their anti-inflammatory effects, we hypothesized that low-dose OA + UA combination downregulates the IL-8 axis and decreases the growth of BPH cells. We found that low-dose OA + UA combination inhibited BPH cell growth and expression of the IL-8 axis. This finding suggests a potential treatment avenue for reducing the overall volume of BPH and thereby reducing LUTS.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Developmentally distinct BPH cell lines

Cell lines representing stages of BPH development were kindly provided by Dr Simon Hayward (NorthShore Medical Center, Evanston, IL) with permission from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN. These are NHPrE1 (NHP), BHPrE1 (BHP), and BPH-1.46–49 NHP and BHP cells were cultured in the “HPrE-culture medium.”46 BPH-1 cells were cultured in RPMI + 10% fetal bovine serum + gentamicin. Immortalized, non-tumorigenic peripheral prostate epithelial cell line, RWPE-1 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in Keratinocyte SFM (Supporting Information Table S1).

2.2 |. Reagents

Antibodies used for immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) are listed in Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2. OA was purchased from TCI America, Portland, OR. UA was purchased from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI. Cytokine arrays, specialized culture media, and IL-8 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit were purchased from commercial sources (Supporting Information Table S1).

2.3 |. Prostate tissues

De-identified prostate tissue and urine specimens were obtained at the University of Miami under an approved human subjects’ protocol and were transferred to Augusta University under an approved protocol. Adult normal prostate specimens (NP; n = 7, age 21-50 years) from organ donors and BPH specimens were obtained from the transitional zone of the prostate (n = 22, 55-75 years) following transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Flash-frozen samples (∼30 mg) were used for total RNA extraction and for the preparation of tissue extracts using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, protease cocktail, and 1% NP-40), as described before.50,51 We homogenized the tissues in HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) buffer (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, plus protease inhibitor cocktail). Urine samples were obtained from men presenting with BPH (n = 8), men without the diagnosis of BPH, but with asymptomatic microhematuria (n = 3), prostatitis (n = 1), and age-matched healthy volunteers (n = 2). Female cases presenting with LUTS included urinary tract infection (n = 3), hematuria (n = 1), and urgency (n = 1).

2.4 |. Primary cultures

BPH tissues from the transitional zone of the prostate from patients undergoing TURP were obtained at Augusta University under an Institutional Review Board for human subjects’ protocol. Tissues were dissociated within 30 minutes of surgery, and cultures were set up in EPiGRO serum-free medium.52 For organoid cultures, following tissue dissociation, ∼1 × 105 cells were inoculated in growth-factor free Matrigel droplets in prostate organoid culture medium as described by Drost et al.52 All primary cultures were used for experiments within three passages and also frozen for later use.

2.5 |. Analysis of transcript expression

Total RNA isolated from the transfectants was reverse-transcribed and further analyzed by RT-qPCR for determining the relative levels of specific transcripts; please see Supporting Information Table S2 for a list of PCR primers. The Mfold Web Server program (University of Albany, NY) was used to select an ideal template sequence, devoid of any secondary structures, for primer design. Primers were designed using the Primer3 Input (current version: 0.4.0) program for primer design.53 All primer pairs had the same Tm at 60°C and were selected to minimize primer dimers. NCBI Primer-BLAST was performed on all primer pairs to ensure target specificity. PCR amplifications were carried out in Quant Studio 3 Real-time PCR thermocycler (Applied Biosystems/Thermo Fisher Scientific). The transcript levels were normalized to β-actin transcript levels, and calculated, as described before.54

2.6 |. Immunoblotting, quantitative immunoassays, and immunohistochemistry

Tissue and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for various proteins. Supporting Information Table S1 has a list of all antibodies used for immunoblotting. Samples were normalized based on total protein and β-actin; protein concentration was measured using DC Protein Assay from Bio-Rad. In each blot, all sample lanes were run on the same gel with the same exposure time; a gap denotes those samples that were not contiguous within the same gel. We used a commercial ELISA kit and the provided instructions (Invitrogen Inc) to measure IL-8 levels in urine specimens and serum-free culture condition media. Briefly, we thawed the frozen samples and clarified by centrifugation (10 000g) and added to precoated wells in the microtiter ELISA plates. IL-8 levels were normalized to creatinine content in the urine, and we counted cells to determine the cell density of the culture wells. Serum-free cell-conditioned media (CM) were used to profile cytokines expressed in BPH lineage cell lines using the protocol provided by the supplier (Ray Biotech Inc, Norcross, GA). The intensity of the individual spots was digitized and quantified against built-in standards using the Image J program (installed from NIH). Following background subtraction, the spot intensity was normalized to 105 cells. BPH tissues were stained for R1, R2, R7, IL-8, and CXCL12 by immunohistochemistry, as described previously.55

2.7 |. Generation of R7 knockout transfectants

Total protein knockout (KO) of R7 was achieved in BPH-1 cells by CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing approach. An R7 CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) sequence (TTTGCACGTGAGCTCGCCCA) was synthesized using a CRISPR software (https://zlab.bio/guide-design-resources) and cloned into the pCas-Guide-EF1a-GFP CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid, as described before.56 BPH-1 cells were stably transfected with the plasmid, and after 72 hours, cells were plated at single-cell dilutions into 96-well plates for clonal expansion. Due to random insertion or deletion mutations (InDels) resulting from CRISPR/Cas9, clonal expansion was necessary to obtain homogeneous cell populations. R7 knockdown was confirmed by immunoblotting.

2.8 |. Statistical analysis

We used the Mann-Whitney U test to determine the significance of the differences in transcript levels between groups (eg, NP vs BPH) when the data were non-normally distributed as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. An unpaired t test was used when the data were normally distributed (R7 and R4 transcript levels). For all analyses, reported P-values are two-tailed. Mean ± SD or mean ± SEM were computed for quantifiable parameters. Differences among the transfectants or treatment groups were compared by one-way AN-OVA followed by an unpaired t test. IC50 for OA, UA, or their combination was determined by a nonlinear regression variable slope (four parameters) model from log10 (inhibitor) vs response (growth) model using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Inc, San Diego, CA). Analysis of OA and UA interaction in the combination (ie, synergy) was performed using the Compusyn software (Combosyn Inc, Paramus, NJ).57,58

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Upregulation of IL-8 axis in BPH specimens

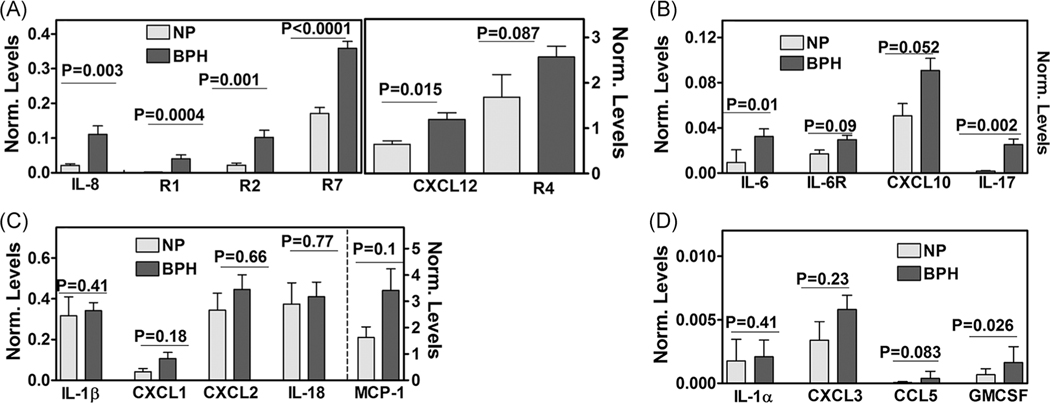

The levels of chemokines and cytokines are elevated in serum, seminal plasma, and urine of symptomatic BPH patients.59–61 It is unknown if these cytokines and chemokines are produced by the prostatic epithelial cells, stroma, or both. We compared the relative levels of 19 transcripts encoding chemokines or their receptors in NP and BPH tissues. Consistent with the pro-inflammatory milieu, we found a significant elevation of the levels of IL-8, IL-6, IL-17, CXCL12, and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) transcripts in BPH tissues when compared to NP (Figure 1A–D). Overall, there was high expression of CXCL10, IL-1β, IL-18, and MCP-1 (ie, CCL2) transcripts in both NP and BPH tissues; however, any observed differences in the expression between NP and BPH tissues were not statistically significant (P > .05). Among the differentially expressed chemokines in the BPH tissues, IL-8 transcript levels were threefold to sixfold higher than IL-6, CXCL10, IL-17, CXCL12, and GM-CSF transcripts, suggesting a plausible role of IL-8 in BPH pathophysiology. While IL-6 receptor transcript was not differentially expressed, the transcript levels of IL-8 and its receptors (R1 and R2) were 5- to 25-fold higher in BPH tissues than in NP tissues (Figure 1A,B). We previously reported that the expression of R7, a receptor for CXCL12, is upregulated by IL-8.18 In BPH tissues, R7 transcript levels were 2.5-fold higher when compared to NP tissues (Figure 1A). CXCR4 (R4) is another receptor for CXCL12, but R4 was not differentially expressed in BPH tissues.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of chemokines and receptors in prostate tissues. (A-D) Transcript levels of chemokines and chemokine receptors indicated in each figure were measured in fresh-frozen normal prostate (NP; n = 7) and BPH (n = 21) tissues by RT-qPCR and normalized to β-actin transcript levels. Data: mean ± SEM; P-values two-tailed; the Mann-Whitney U test. BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; IL-8, interleukin-8; R1, CXCR1; R2, CXCR2; R7, CXCR7; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

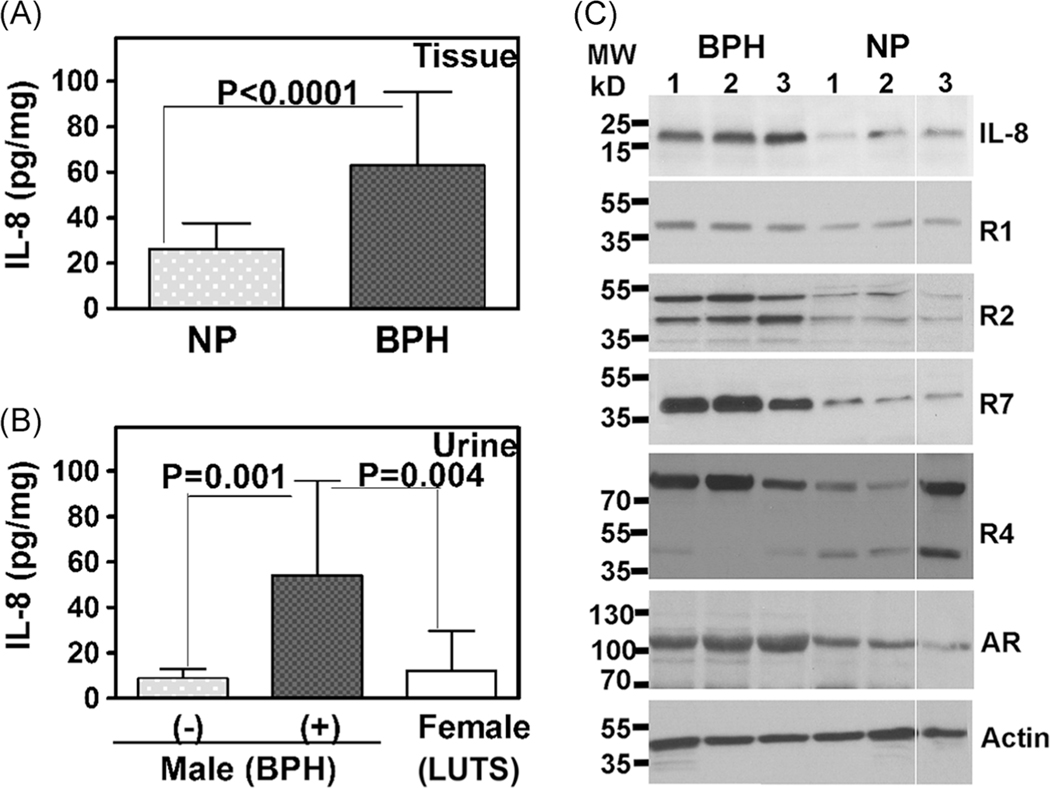

Next, we measured IL-8 protein levels in prostate tissue extracts (prepared in HEPES buffer) and urine specimens. Consistent with the increase in transcript levels, IL-8 protein levels were 2.4-fold higher in BPH tissues than in NP tissues (Figure 2A). IL-8 levels were also threefold to sixfold elevated in urine specimens from patients with BPH/LUTS compared to age-matched asymptomatic men and female patients presenting with LUTS (Figure 2B). These results show that IL-8 upregulation is likely associated with BPH but not with non-BPH–related LUTS. Immunoblot analysis showed threefold to eightfold upregulation of IL-8, R1, R2, and R7 protein levels in BPH tissues when compared to NP tissues (Figure 2C and Supporting Information Table S3). However, R4 expression was not consistently and significantly altered in BPH specimens (Figure 2C). Androgen receptor (AR) was expressed in both BPH and NP tissues, although AR levels were slightly higher in BPH specimens (Figure 2C and Supporting Information Table S3).

FIGURE 2.

Expression of IL-8 axis in prostate tissues. A, IL-8 levels were measured in normal prostate (NP; n = 4) and BPH (n = 7) tissues by ELISA in quadruplicate and the levels (pg/mL) were normalized to total protein (mg/mL); IL-8 levels are expressed as pg IL-8 per mg protein (pg/mg). B, Urinary IL-8 levels were measured in males (n = 14); BPH (−): 6; BPH (+): 8 and females (n = 5). No BPH cases in males include asymptomatic microhematuria (n = 3), prostatitis (n = 1), and age-matched volunteer (n = 2). Female cases presenting with LUTS included urinary tract infection (n = 3), hematuria (n = 1), and urgency (n = 1). Data in A and B: mean ± SEM; P-values two-tailed; the Mann-Whitney U test. C, Immunoblot analysis of IL-8, IL-8 receptors, and R7 in NP and BPH tissue lysates (6 μg protein); Actin: loading control. Note: In each blot, all sample lanes were run on the same gel with the same exposure time; a solid line denotes those samples that were not contiguous within the gel. BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL-8, interleukin-8; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; NP, normal prostate

3.2 |. Expression of the IL-8 axis in primary BPH cultures

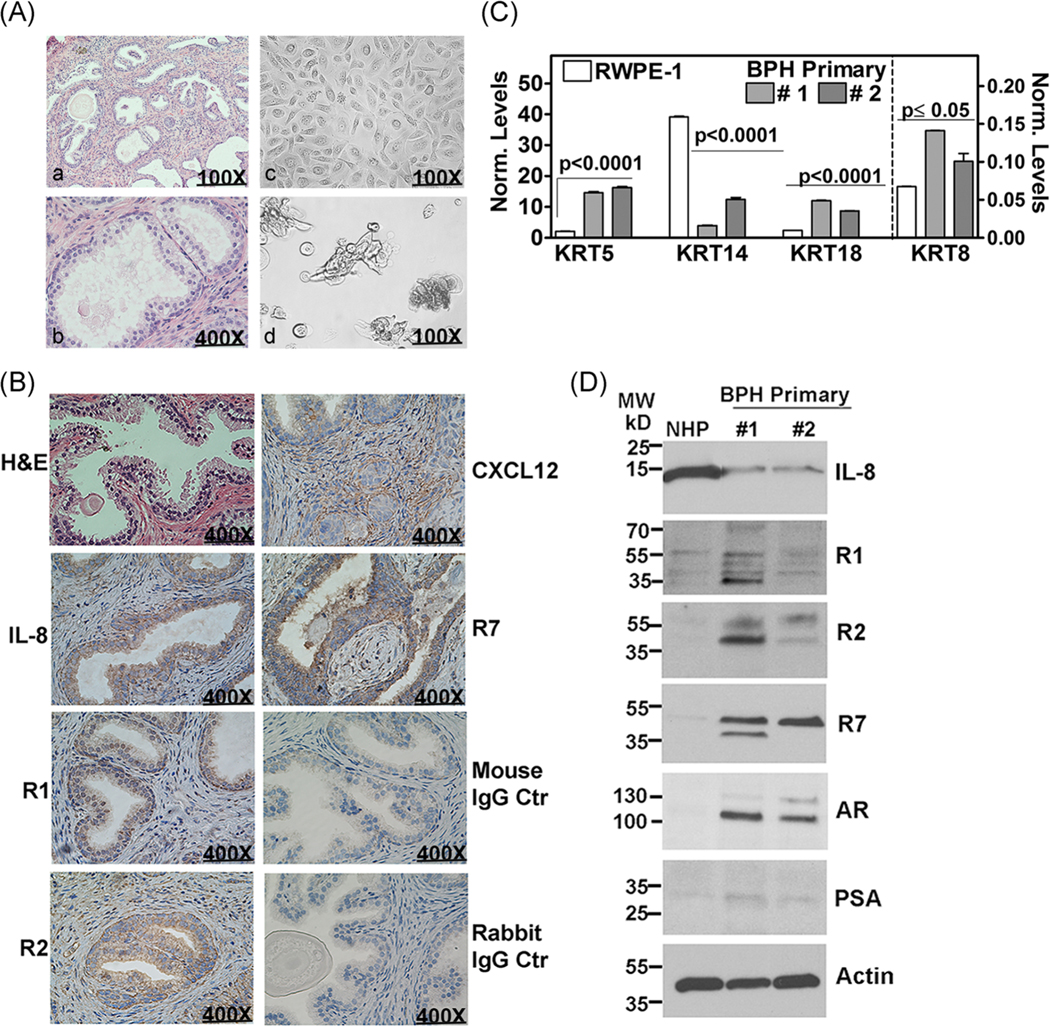

We established primary explant cultures from the tissues obtained from TURP. A small portion of the prostate tissue chips was also fixed for histology to confirm the diagnosis of BPH (Figure 3A–a,b,B). The attached monolayer of cells showed epithelial morphology, and organoids were formed when the explants were grown in Matrigel 3D culture conditions (Figure 3A–c,d). The explant cultures expressed cytokeratins (KRT) 5, 8, and 18, and their expression was 2- to 10-fold higher in BPH explant cultures than in RWPE-1 (Figure 3C). Contrarily, the expression of KRT14 was 3.5- to 10-fold decreased in BPH explant cultures (Figure 3C). Based on the cytokeratin expression pattern, these primary cells were acinar-luminal, but not basal epithelial cells.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of primary BPH cultures regarding the growth and IL-8 axis. A, BPH primary culture; a, b: H & E staining of a representative BPH tissue used for establishing primary cultures. c, d: Representative picture of 2D (c) and organoid cultures (d) established from the BPH specimen shown in a and b. B, H & E staining and immunohistochemistry analysis of a BPH specimen for chemokines (IL-8, CXCL12) and chemokine receptors (R1, R2, and R7). Negative control: the specimen was stained with the isotype-matched mouse or rabbit IgG as control. C,D, Primary cultures #1 and # 2 were established from BPH specimens shown in A and B, respectively. 2D cultures were analyzed for cytokeratin expression by RT-qPCR (C); transcript levels were normalized to β-actin transcript levels. Data: mean ± SD. Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from NHP and primary cultures for indicated proteins. Actin: loading control (D). BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; H & E, hematoxylin and eosin; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL-8, interleukin-8; R1, CXCR1; R2, CXCR2; R7, CXCR7; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

We next performed immunohistochemistry of specimens that were used for establishing primary explant cultures for the expression of IL-8 axis members. As shown in Figure 3B, the expression of IL-8, R1, R2, and R7 was confined to prostate luminal epithelial cells, whereas the expression of CXCL12 (ligand for R4 and R7) was mostly observed in the stromal compartment. Immunoblot analysis showed that explant cultures express both AR and prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which further confirmed that these are prostatic epithelial cells established from BPH specimens (Figure 3D). The expression of R1, R2, and R7 proteins was greater than or equal to fivefold higher in the explant cultures compared to those in NHP cells, which are characterized as putative prostate progenitor cells.46,49 Further, IL-8 expression was 2.5- to 3-fold higher in NHP cells as compared to that of the explant cultures (Figure 3D). Interestingly, we found the receptors of the IL-8 axis upregulated in BPH samples and BPH-derived primary cultures but not in NP.

3.3 |. IL-8 axis members are differentially expressed in developmentally distinct BPH cells

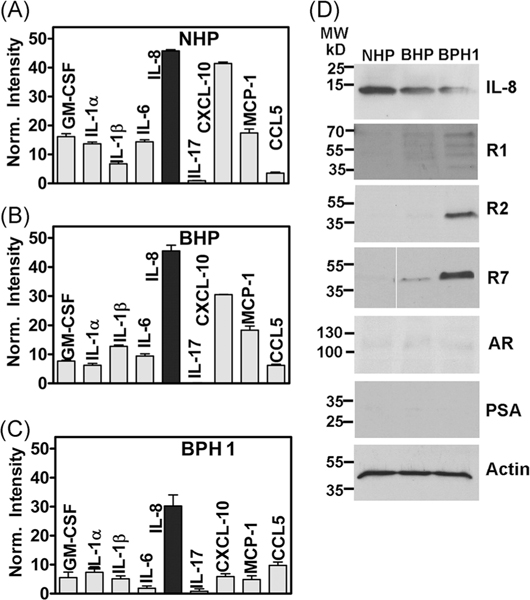

To confirm the upregulation of IL-8 axis in BPH-derived prostate epithelial cells, we compared the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the CM of three BPH lineage cell lines—NHP, BHP, and BPH-1. NHP (CD133hi/CD44hi/OCT4hi/PTENhi) was characterized as a putative progenitor cell. BHP (p63hi/p53 hi/p21 (WAF1)hi/RB hi) was characterized as a putative epithelial intermediate cell.49 BPH-1 is a non-tumorigenic epithelial cell line derived from human prostate tissue obtained by transurethral resection.47 These cell lines did not express AR or PSA, although (5-α)-reductase, 3-α-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase, and 17 β-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase activities are reported in BPH-1 cells.47,62 Utilizing a human inflammation cytokine array, we detected the same nine chemokines in the CM of all three cell lines that were expressed in BPH specimens (Figures 1 and 4A–D). Consistent with the expression pattern in BPH specimens, IL-8 was highly expressed in the CM of all three BPH lineage cell lines; IL-8 levels were about 1.5-fold higher in NHP and BHP cells as compared to BPH-1 cells (Figure 4A–C). Immunoblot analysis confirmed higher IL-8 expression in NHP and BHP cells, as compared to BPH-1 cells (Figure 4D). However, only BPH-1 cells expressed detectable and high levels of R1, R2, and R7 (Figure 4D). As has been previously reported,47,62 all three cell lines did not express AR or PSA (Figure 4D). Compared to BPH-1 cells, the R7 and IL-8 transcripts in RWPE-1 cells were 10- to 80-fold lower, and the R1 and R2 transcripts were undetectable (Supporting Information Figure S1–A).

FIGURE 4.

Chemokine and receptor expression in BPH lineage cell lines. A-C, Cytokine and inflammation array analysis performed on the cell-conditioned media of BPH lineage cell lines in duplicate. Data (mean ± SEM) shown are for detectable cytokines. D, Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from NHP and primary cultures for indicated proteins. Actin: loading control. BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; IL-8, interleukin-8; NHP, NHPrE1; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; R1, CXCR1; R2, CXCR2; R7, CXCR7

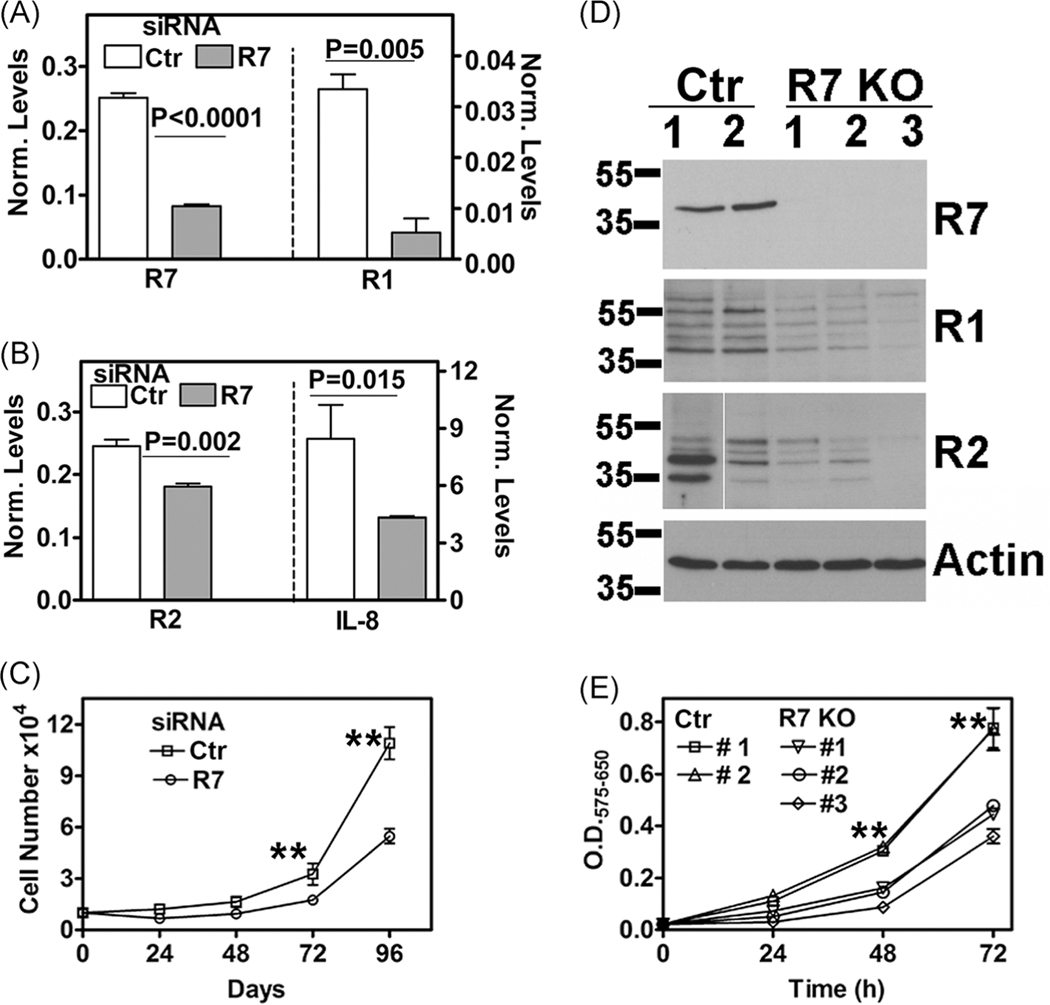

3.4 |. R7 regulates IL-8 axis and BPH-1 cell proliferation

We have previously shown that R7 depletion reduces the proliferation of prostate cancer cells.18,56 Since R7 was expressed in BPH-1 cells but not in NHP and BHP cells, we downregulated R7 in BPH-1 cells by transient small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection. In R7 siRNA transfectants, not only was R7 messenger RNA (mRNA) depleted by about 70%, the IL-8, R1, and R2 levels were also downregulated by 33% to 80% (Figure 5A,B). The decrease in other IL-8 axis components was statistically significant and coincided, with a reduction in cell proliferation (Figure 5C). In a cell proliferation assay, at each time point, the growth of R7 siRNA transfectants was inhibited by greater than or equal to 50% (P < .0001). Next, we generated stable R7 KO transfectants by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene editing. As shown in Figure 5D, R7 KO transfectants not only showed a complete knockdown of R7 protein, but compared to the control transfectants, R1 and R2 expression were also downregulated fivefold to eightfold in R7 KO transfectants. In cell proliferation assays, the growth of R7 KO transfectants was greater than or equal to 50% slower than the control transfectants at each time point (P < .0001) (Figure 5E).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of R7 knockout on IL-8 axis and BPH-1 cell growth. A-C, Expression of IL-8 axis and growth in BPH-1 cells transiently transfected with control/scrambled siRNA or R7 siRNA. A,B, Analysis of IL-8 axis transcripts by RT-qPCR; the levels were normalized to β-actin transcript levels. C, Cell proliferation measured by cell counting. D,E, Characterization of R7 and control transfectants following CRISPR gene knockout. D, Immunoblot analysis for indicated proteins. E, Cell growth measured by MTT assay; data showed are sample OD (575 nm)-reference OD (650 nm). Data in A,B, C, and E: mean ± SD (n = 3 to n = 4). **P ≤ .001. BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; IL-8, interleukin-8; KO, knockout; R1, CXCR1; R2, CXCR2; R7, CXCR7; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; siRNA, small interfering RNA

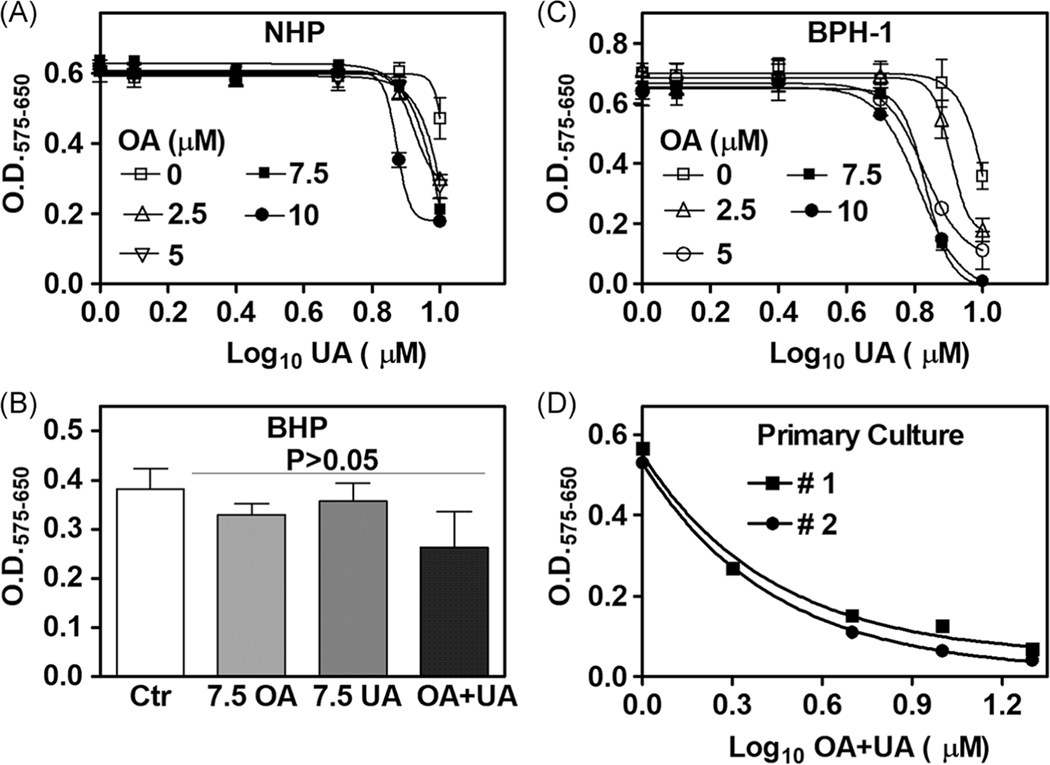

3.5 |. OA+UA combination inhibits BPH growth and downregulates the IL-8 axis

We evaluated whether low-doses of OA and UA, either alone or in combination, would inhibit the growth of NHP, BHP, and BPH-1 cells. OA and UA have been shown to affect several cellular targets at high doses (40 – 438 μM), but their effects at low-doses (≤ 10 μM) are not reported.21–28 OA + UA combination marginally inhibited the growth of NHP and BHP cells (Figure 6A,B). Treating BPH-1 cells with OA + UA combination caused significant dose-dependent growth inhibition (Figure 6C). Analysis of synergy using the Compusyn software showed that OA and UA combination inhibited BPH-1 cell growth with strong synergy (combination index: 0.061). Synergy analysis also showed that 50% growth inhibition (Fa = 0.5) was achieved by combining 4.1 μM UA + 5.47 μM OA. Further, it would require 67 μM of UA alone and 42,990 μM (ie, ∼ 43 mM) of OA alone to achieve 50% growth inhibition. Therefore, the combination resulted in a dose reduction index of 16.4-fold for UA and 7852-fold for OA, suggesting that OA + UA combination effectively inhibited BPH-1 cell growth at significantly reduced doses compared to UA or OA alone.

FIGURE 6.

Cytotoxic effects of OA, UA, and OA + UA combination in BPH lineage cells and primary BPH cultures. A-D, Twenty-four cultures of NHP, BHP, two primary BPH cultures (1 × 103 cells/well), and BPH-1 (5 × 103 cells/well) cultured in respective growth media were treated with various concentrations of OA, UA, or the combination for 72 hours. Cell growth measured by MTT assay; data: mean ± SD (n = 4). A,C, UA dose is shown as log10. D, OA + UA combined dose is shown as log10. A,C,D, Both actual data points and nonlinear regression curve fitting are shown. BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; NHP, NHPrE1; OA, oleanolic acid; UA, ursolic acid

We also examined if the combination could inhibit the growth of primary BPH explant cultures. As shown in Figure 6D, the OA + UA combination caused a dose-dependent decrease in the growth of two primary BPH explant cultures, and the IC50 for the OA + UA combination was ∼1.7 μM (ie, a drug mixture of 0.85 μM UA + 0.85 μM OA). The growth inhibition of BPH cells by OA + UA combination treatment was not due to apoptosis, as the combination did not induce cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) (Supporting Information Figure S1–B). However, as compared to OA and UA alone, cytotoxic autophagy was observed in OA + UA-treated BPH-1 cells. The levels of long chain 3B (LC3B), a definitive autophagy biomarker, were 1.7- to 4.4-fold elevated (Supporting Information Figure S1–B). This observation suggested that the growth inhibition caused by the OA + UA combination was likely due to the induction of cytotoxic autophagy.

It has been shown that both OA and UA have anti-inflammatory effects, but the doses used in many of the studies are 10- to 40-fold higher than the low-dose combination, which inhibited the growth of BPH-1 cells.21–23,26–28,63–69 Because R7 knockdown inhibited BPH-1 cell growth and inhibited IL-8 axis, we investigated if OA, UA, and the combination could inhibit IL-8 axis. As shown in Supporting Information Figure S1–C, IL-8 levels were downregulated by ∼30% in OA + UA-treated cells. OA alone caused a 75% decrease in R1 mRNA expression (Supporting Information Figure S1–D). At the same dose, UA alone downregulated both R1 and R2 mRNA levels by 75% to 90% (Supporting Information Figure S1–E) but increased R7 mRNA levels by 2.4-fold (Supporting Information Figure S1–F). The combination of OA + UA consistently decreased R1, R2, and R7 transcript levels by 75% to 95% (Supporting Information Figure S1C–F). These results demonstrate that the OA + UA combination treatment downregulates the IL-8 axis and inhibits BPH growth.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Cytokines, including pro-inflammatory chemokines, are the main drivers of the chronic inflammatory processes associated with the BPH etiology and symptom severity.9,11,13,15,16 Our study supports an inflammatory etiology of BPH. It demonstrates that the epithelial compartment of BPH tissue is both a recipient of and a contributor to the inflammatory milieu in BPH. The salient findings of our study are (a) pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, and CXCL10, are differentially expressed in BPH specimens compared to NP tissues; (b) IL-8 axis comprising of IL-8, its cognate receptors (R1 and R2) and R7, is a major chemokine pathway that is elevated in tissue and urine specimens from BPH patients; (c) prostate epithelial cells of BPH origin (ie, primary cultures; BPH-1 cell line), but not the progenitor (NHP, BHP), and RWPE-1 cells, express functional IL-8 axis; (d) R7 KO inhibits BPH-1 cell growth and downregulates IL-8 axis levels in a feedback loop; (e) low-dose combination of OA and UA inhibits BPH cell growth by inducing autophagy and down-regulating the IL-8 axis.

Analysis of cytokines showed that contrary to the inflammatory milieu in BPH, the normal prostate has a significantly lower level of inflammatory chemokines. NP tissues obtained from the peripheral zone showed relatively low expression of inflammatory cytokines. In contrast, BPH tissues obtained from the transitional zone of the prostate abundantly expressed pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The transitional zone mainly gives rise to hyperplasia and fibrosis due to the increased proliferation of both epithelial and smooth muscle cells. The pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-8, CXCL10, and IL-17 that were found to be upregulated in BPH specimens, modulate immune cell functions in situ.9,11,14,15 The same cytokines were also expressed and secreted by the primary epithelial explant cultures and/or BPH-1 cells, suggesting that epithelial cells of BPH origin are capable of creating a niche for the inflammatory process in which immune cells such as monocytes, neutrophils, and T-cells support a favorable environment for epithelial hyperplasia.14,70 Our results also showed that IL-8 transcript levels were threefold to sixfold higher in BPH specimens when compared to IL-6, IL-17, CXCL10, and GM-CSF levels. Furthermore, the levels of IL-8 receptors and R7 were greater than fivefold elevated in BPH specimens when compared to NP tissues. This observation suggests that the IL-8 axis plays a predominant role in creating an inflammatory environment in the transitional zone of the prostate that contributes to hypertrophy and glandular expansion. A caveat in this study is that NP tissues were obtained from men ages 21 to 50 years, whereas BPH specimens were from patients 55 to 75 years old. It is possible that some of the differences in chemokine and chemokine receptor expression were age-related. However, urinary IL-8 levels were significantly elevated in age-matched men with BPH/LUTS when compared to men without BPH and females presenting with LUTS. Based on the data on NHP, BHP, and BPH-1 cells, IL-8 expression appears to precede the expression of its receptors; therefore, the observed elevation of the IL-8 axis in patients with BPH very likely is related to disease pathophysiology.

While the normal prostate epithelial cells express low levels of all members of the IL-8 axis, two spontaneously immortalized cell lines NHP and BHP secrete high levels of the IL-8 but do not express IL-8 receptors or the downstream targets which promote BPH cell growth. It is plausible that in a paracrine role, IL-8 secreted by these progenitor-like cells initiates an inflammatory process by attracting immune cells (eg, neutrophils and leukocytes) into the prostate. These immune cells, in turn, exacerbate the pro-inflammatory microenvironment by secreting IL-6 and IL-17. It was recently reported that in a mouse model of BPH, created by injecting LPS directly into the urethra, IL-6 and IL-17 were the predominant pro-inflammatory factors detected in the mouse prostate. However, KC, the murine homolog of IL-8, was not evaluated in this study, and therefore, the plausible contribution of IL-8 in the development of BPH in mice remains unexplored.71,72

We previously reported that the constitutive expression of IL-8 elevates R7 in prostate cancer cells (LNCaP), and the cells become less dependent on androgen for growth.73,74 In BPH progenitor cells, IL-8 signaling is inactive because they do not express IL-8 receptors, and consequently, also lack R7 expression and its growth stimulatory effects. It is unclear how the IL-8 axis becomes fully functional in BPH cells. It is plausible that BPH progenitor cells need to interact with inflammatory immune cells to express R1 and R2, and consequently, to express IL-8 signaling-induced transcriptome, including R7. A seminal finding of our study is the possibility of a feedback mechanism between R7 and IL-8 signaling. R7 KO in BPH-1 cells decreased R1, R2, and IL-8 expression, which was accompanied by growth inhibition. One explanation for the observed growth inhibition in R7 KO cells is the suppression of EGFR-induced mitogenic signaling, which is regulated by both R1 and R7 in prostate epithelial cells.19,56,74

Our study suggests that low-dose combination of natural compounds, such as—UA and OA—which are nontoxic to normal cells, could potentially be used for the treatment of BPH. The combination inhibited the growth of BPH-1 cells at 16.4- to 7852-fold reduced doses of UA and OA alone, respectively. OA + UA also inhibited the growth of primary BPH cultures with an IC50 of 1.7 μM (or 0.85 μM of each drug alone). The fact that it will require an estimated 67 μM of UA and 43 mM of OA to achieve the same effect may explain the use of high doses of UA and OA in published studies.21–28 The efficacy of the combination at low-dose demonstrates that the combination could potentially have efficacy in vivo at pharmacologically achievable doses with minimal toxicity.26,29,30 Our data show that this growth inhibition is likely related to their anti-inflammatory activities.75 Downregulation of IL-8 axis expression by OA + UA combination may also explain why the combination was only weakly cytotoxic to NHP and BHP cells, which express high levels of IL-8 but do not express R1, R2, and R7.

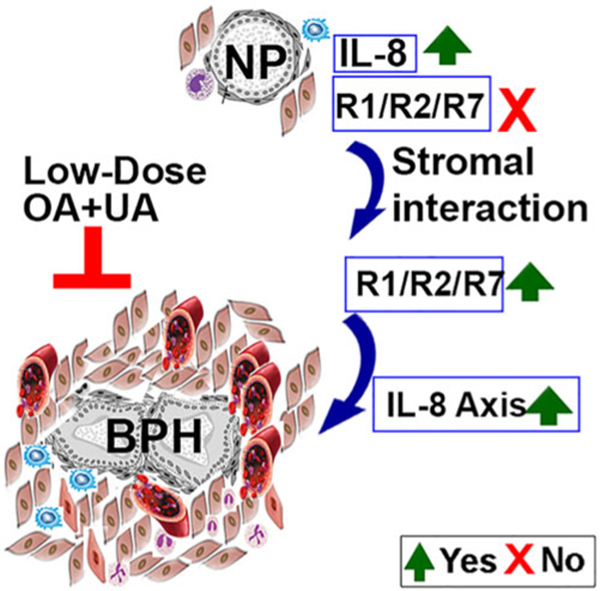

The growth of the prostate gland beyond adolescence is poorly understood. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors control BPH and LUTS secondary to it. Our study demonstrates a likely hierarchy in the roles of various cytokines in promoting chronic inflammation and prostate epithelial growth. Based on our data, we propose a model for the functional role of the IL-8 axis in the development of BPH. We suggest that prostate epithelial progenitor cells and epithelial cells derived from BPH tissues secrete high levels of IL-8, which in turn, generates an inflammatory milieu by attracting immune cells capable of creating a chronic inflammatory condition. Further escalation of this inflammatory cell population and the corresponding secretion of cytokines stimulates the proliferation of both epithelial and stromal smooth muscle cells, leading to glandular hyperplasia and fibrosis. These two main factors contribute to urethral constriction and subsequent LUTS (Figure 7). Furthermore, an orally bioavailable combination of OA and UA may abrogate the inflammation-triggered development of prostatic hyperplasia by inhibiting the IL-8 axis and should be considered for evaluation in phase I clinical trials.

FIGURE 7.

IL-8 axis in the development of BPH. The schematic shows that IL-8 expressing epithelial cells in the prostate, attract inflammatory cells to create an inflammatory milieu. Inductive stromal cells in the inflammatory milieu induce the expression of R1 and R2. This activates IL-8 signaling and induces R7 expression. The functional IL-8 axis and plausibly other pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate the proliferation of both epithelial and stromal smooth muscle cells leading to glandular hyperplasia and fibrosis. Low-dose OA and UA combination downregulates the expression of IL-8 axis and may consequently inhibit BPH cell growth. BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; IL-8, interleukin-8; NP, normal prostate; OA, oleanolic acid; R1, CXCR1; R2, CXCR2; R7, CXCR7; UA, ursolic acid

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for extensive discussions with Drs. Wade Bushman and William A. Ricke, both from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, and Dr. Jill McCoska, Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy, University of Massachusetts, Boston, MA on prostate inflammation, fibrosis, and BPH models. We believe these discussions improved our work. The research reported in this publication was partly supported by the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Developemnt, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Grant # I01BX003862-02 (BLL); National Institute of Health, under the awards 1R01CA227277-02A1 (VBL), 1F31CA236437-01 (DSM), and 1F31CA210612-01 (ARJ) and United States Army Medical Research and Development Command (USAMRDC) of the Department of Defense Grant # W81XWH-18-1-0227.

Funding information

Biomedical Laboratory Research and Developemnt, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Grant/Award Number: 5I01BX003862-0 2; National Institute of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: 1R01CA227277-02A1, 1F31CA236437-01, 1F31CA210612-01; United States Army Medical Research and Development Command (USAMRDC) of the Department of Defense, Grant/Award Number: W81XWH-18-1-0227.

Abbreviations:

- BHP

BHPrE1

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- LUTS

lower urinary tract symptoms

- NHP

NHPrE1

- NP

normal prostate

- OA

oleanolic acid

- R1

CXCR1

- R2

CXCR2

- R7

CXCR7

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- UA

ursolic acid

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100): 1211–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaron L, Franco OE, Hayward SW. Review of prostate anatomy and embryology and the etiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Clin North Am. 2016;43(3):279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNeal J. Pathology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Insight into etiology. Urol Clin North Am. 1990;17(3):477–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahokehr A, Gilling PJ. Landmarks in BPH—from aetiology to medical and surgical management. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(2):118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lokeshwar SD, Harper BT, Webb E, et al. Epidemiology and treatment modalities for the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8(5):529–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vuichoud C, Loughlin KR. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: epidemiology,economics and evaluation. Can J Urol. 2015;22(Suppl 1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bushman W. Etiology, epidemiology, and natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Clin North Am. 2009;36(4):403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch JL, Bangma CH, Groeneveld FP, Bohnen AM. The long-term relationship between a real change in prostate volume and a significant change in lower urinary tract symptom severity in population-based men: the Krimpen study. Eur Urol. 2008;53(4):819–825. Discussion 25-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fibbi B, Penna G, Morelli A, Adorini L, Maggi M. Chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Androl. 2010; 33(3):475–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vital P, Castro P, Tsang S, Ittmann M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype promotes benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2014;184(3):721–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konig JE, Senge T, Allhoff EP, Konig W. Analysis of the inflammatory network in benign prostate hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Prostate. 2004;58(2):121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park HJ, Won JE, Sorsaburu S, Rivera PD, Lee SW. Urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS/BPH with erectile dysfunction in Asian men: a systematic review focusing on tadalafil. World J Mens Health. 2013;31(3): 193–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyagi P, Motley SS, Kashyap M, et al. Urine chemokines indicate pathogenic association of obesity with BPH/LUTS. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(7):1051–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ao M, Franco OE, Park D, Raman D, Williams K, Hayward SW. Cross-talk between paracrine-acting cytokine and chemokine pathways promotes malignancy in benign human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4244–4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyagi P, Motley SS, Koyama T, et al. Molecular correlates in urine for the obesity and prostatic inflammation of BPH/LUTS patients. Prostate. 2018;78(1):17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowke JH, Koyama T, Fadare O, Clark PE. Does inflammation mediate the obesity and BPH relationship? An epidemiologic analysis of body composition and inflammatory markers in blood, urine, and prostate tissue, and the relationship with prostate enlargement and lower urinary tract symptoms. PLOS One. 2016;11(6):e0156918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culig Z, Puhr M. Interleukin-6 and prostate cancer: current developments and unsolved questions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;462(Pt A):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh RK, Lokeshwar BL. The IL-8-regulated chemokine receptor CXCR7 stimulates EGFR signaling to promote prostate cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71(9):3268–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamaladevi N, Lyn DA, Escudero DO, Lokeshwar BL. CXC receptor-1 silencing inhibits androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(21):8265–8274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coniglio SJ. Role of tumor-derived chemokines in osteolytic bone metastasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caunii A, Oprean C, Cristea M, et al. Effects of ursolic and oleanolic on SKMEL2 melanoma cells: in vitro and in vivo assays. Int J Oncol. 2017; 51(6):1651–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao L, Wang Y, Xu Z, et al. SZC017, a novel oleanolic acid derivative, induces apoptosis and autophagy in human breast cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2015;20(12):1636–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ES, Moon A. Ursolic acid inhibits the invasive phenotype of SNU-484 human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(2):897–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, Kim YH, Song GY, et al. Ursolic acid and its natural derivative corosolic acid suppress the proliferation of APC-mutated colon cancer cells through promotion of beta-catenin degradation. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;67:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J. Pharmacology of oleanolic acid and ursolic acid. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;49(2):57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanmugam MK, Ong TH, Kumar AP, et al. Ursolic acid inhibits theinitiation, progression of prostate cancer and prolongs the survival of TRAMP mice by modulating pro-inflammatory pathways. PLOS One. 2012;7(3):e32476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Liu L, Qiu H, et al. Ursolic acid simultaneously targets multiple signaling pathways to suppress proliferation and induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells. PLOS One. 2013;8(5):e63872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang RX, Li Y, Tian DD, et al. Ursolic acid inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis by inactivating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in human osteosarcoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2016;49(5):1973–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayeleso TB, Matumba MG, Mukwevho E. Oleanolic acid and its derivatives: biological activities and therapeutic potential in chronic diseases. Molecules. 2017;22:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seo DY, Lee SR, Heo JW, et al. Ursolic acid in health and disease. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;22(3):235–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wozniak L, Skapska S, Marszalek K. Ursolic acid——a pentacyclic triterpenoid with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities. Molecules. 2015;20(11):20614–20641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuttan G, Pratheeshkumar P, Manu KA, Kuttan R. Inhibition of tumor progression by naturally occurring terpenoids. Pharm Biol. 2011; 49(10):995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mlala S, Oyedeji AO, Gondwe M, Oyedeji OO. Ursolic acid and its derivatives as bioactive agents. Molecules. 2019;24(15):2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanmugam MK, Manu KA, Ong TH, et al. Inhibition of CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling axis by ursolic acid leads to suppression of metastasis in transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(7):1552–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang SM, Yee ST, Choi J, et al. Ursolic acid enhances the cellular immune system and pancreatic beta-cell function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice fed a high-fat diet. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009; 9(1):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunkel SD, Suneja M, Ebert SM, et al. mRNA expression signatures of human skeletal muscle atrophy identify a natural compound that increases muscle mass. Cell Metab. 2011;13(6):627–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramirez-Rodriguez AM, Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Martinez-Abundis E, Acuna Ortega N. Effect of ursolic acid on metabolic syndrome, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation. J Med Food. 2017;20(9):882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu SG, Zhang CJ, Xu XE, Sun JH, Zhang L, Yu PF. Ursolic acid derivative ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabestic bone deleterious effects in mice. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(4):3681–3690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao S, Wastney ME, Lachcik PJ, Xiao HH, Weaver CM, Wong MS. Both oleanolic acid and a mixture of oleanolic and ursolic acids mimic the effects of fructus ligustri lucidi on bone properties and circulating 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in ovariectomized rats. J Nutr. 2018; 148(12):1895–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Aparicio A, Schmidt-RioValle J, Perona JS, Correa-Rodriguez M, Castellano JM, Gonzalez-Jimenez E. Potential protective effect of oleanolic acid on the components of metabolic syndrome: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.So JY, Wahler JE, Yoon T, et al. Oral administration of a gemini vitamin D analog, a synthetic triterpenoid and the combination prevents mammary tumorigenesis driven by ErbB2 overexpression. Cancer Prev Res. 2013;6(9):959–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Bai H, Zhang X, et al. Inhibitory effect of oleanolic acid on hepatocellular carcinoma via ERK-p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(6): 1323–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bang HS, Seo DY, Chung YM, et al. Ursolic acid supplementation decreases markers of skeletal muscle damage during resistance training in resistance-trained men: a pilot study. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;21(6):651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho YH, Lee SY, Kim CM, et al. Effect of loquat leaf extract on muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle function in healthy adults: a randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:4301621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Church DD, Schwarz NA, Spillane MB, et al. l-Leucine increases skeletal muscle IGF-1 but does not differentially increase Akt/mTORC1 signaling and serum IGF-1 compared to ursolic acid in response to resistance exercise in resistance-trained men. J Am Coll Nutr. 2016; 35(7):627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang M, Min Y, Debusk L, et al. Spontaneous immortalization of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. World J Stem Cells. 2010; 2(5):114–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayward SW, Dahiya R, Cunha GR, Bartek J, Deshpande N, Narayan P. Establishment and characterization of an immortalized but non-transformed human prostate epithelial cell line: BPH-1. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1995;31(1):14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayward SW, Haughney PC, Lopes ES, Danielpour D, Cunha GR. The rat prostatic epithelial cell line NRP-152 can differentiate in vivo in response to its stromal environment. Prostate. 1999;39(3):205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang M, Strand DW, Fernandez S, et al. Functional remodeling of benign human prostatic tissues in vivo by spontaneously immortalized progenitor and intermediate cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(2):344–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kramer MW, Escudero DO, Lokeshwar SD, et al. Association of hyaluronic acid family members (HAS1, HAS2, and HYAL-1) with bladder cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer. 2011;117(6):1197–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lokeshwar VB, Rubinowicz D, Schroeder GL, et al. Stromal and epithelial expression of tumor markers hyaluronic acid and HYAL1 hyaluronidase in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):11922–11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drost J, Karthaus WR, Gao D, et al. Organoid culture systems for prostate epithelial and cancer tissue. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(2):347–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(10):1289–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kallifatidis G, Smith DK, Morera DS, et al. β-arrestins regulate stem cell-like phenotype and response to chemotherapy in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(4):801–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caruso DJ, Carmack AJ, Lokeshwar VB, Duncan RC, Soloway MS, Lokeshwar BL. Osteopontin and interleukin-8 expression is independently associated with prostate cancer recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4111–4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoy JJ, Kallifatidis G, Smith DK, Lokeshwar BL. Inhibition of androgen receptor promotes CXC-chemokine receptor 7-mediated prostate cancer cell survival. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):621–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chou TC, Martin N. CompuSyn for Drug Combinations: PC Software and User’s Guide: A Computer Program for Quantitation of Synergism and Antagonism in Drug Combinations, and the Determination of IC50 and ED50 and LD50 Values. Paramus, NJ: ComboSyn Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kruslin B, Tomas D, Dzombeta T, Milkovic-Perisa M, Ulamec M. Inflammation in prostatic hyperplasia and carcinoma-basic scientific approach. Front Oncol. 2017;7:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lotti F, Maggi M. Interleukin 8 and the male genital tract. J Reprod Immunol. 2013;100(1):54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Norstrom MM, Radestad E, Sundberg B, et al. Progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia is associated with pro-inflammatory mediators and chronic activation of prostate-infiltrating lymphocytes. Oncotarget. 2016;7(17):23581–23593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang S, Jiang M, Grabowska MM, et al. Androgen receptor differentially regulates the proliferation of prostatic epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2016;7(43):70404–70419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hollosy F, Meszaros G, Bokonyi G, et al. Cytostatic, cytotoxic and protein tyrosine kinase inhibitory activity of ursolic acid in A431 human tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(6B):4563–4570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim HI, Quan FS, Kim JE, et al. Inhibition of estrogen signaling through depletion of estrogen receptor alpha by ursolic acid and betulinic acid from Prunella vulgaris var. lilacina. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;451(2):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J, Li N, Yan S, et al. Ursolic acid alleviates inflammation and against diabetes-induced nephropathy through TLR4-mediated inflammatory pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(5):4675–4681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mu DW, Guo HQ, Zhou GB, Li JY, Su B. Oleanolic acid suppresses the proliferation of human bladder cancer by Akt/mTOR/S6K and ERK1/2 signaling. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(11):13864–13870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Son HS, Kwon HY, Sohn EJ, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase3 beta mediate ursolic acid induced apoptosis in HepG2 liver cancer cells. Phytother Res. 2013;27(11):1714–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiang L, Chi T, Tang Q, et al. A pentacyclic triterpene natural product, ursolic acid and its prodrug US597 inhibit targets within cell adhesion pathway and prevent cancer metastasis. Oncotarget. 2015;6(11): 9295–9312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng QY, Li PP, Jin FS, et al. Ursolic acid induces ER stress response to activate ASK1-JNK signaling and induce apoptosis in human bladder cancer T24 cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25(1):206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar RK, O’Grady R, Li W, Rajkovic I. Secretion of epidermal growth factor-like molecular species by lung parenchymal macrophages: induction by interferon-gamma. Growth Factors. 1993; 9(3):223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singer M, Sansonetti PJ. IL-8 is a key chemokine regulating neutrophil recruitment in a new mouse model of Shigella-induced colitis. J Immunol. 2004;173(6):4197–4206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dos Santos Gomes FO, Oliveira AC, Ribeiro EL, et al. Intraurethral injection with LPS: an effective experimental model of prostatic inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2018;67(1):43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Araki S, Omori Y, Lyn D, et al. Interleukin-8 is a molecular determinant of androgen independence and progression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):6854–6862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh RK, Lokeshwar BL. Depletion of intrinsic expression of interleukin-8 in prostate cancer cells causes cell cycle arrest, spontaneous apoptosis and increases the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li S, Liao X, Meng F, et al. Therapeutic role of ursolic acid on ameliorating hepatic steatosis and improving metabolic disorders in high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease rats. PLOS One. 2014; 9(1):e86724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.