Abstract

Purpose:

Recent preclinical data suggest that cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibition may be harnessed to sensitize estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer to radiotherapy. However, these findings were obtained in human ER+ breast cancer cell lines exposed to subclinical doses of CDK4/6 inhibitors with limited attention to treatment schedule. We investigated the activity of radiotherapy combined with the prototypic CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib placing emphasis on therapeutic schedule.

Experimental Design:

We combined radiotherapy and palbociclib in various doses and therapeutic schedules in human and mouse models of ER+ and ER-negative (ER−) breast cancer, including an immunocompetent mouse model that recapitulates key features of human luminal B breast cancer in women. We assessed proliferation, cell death, cell-cycle control, and clonogenic survival in vitro, as well as tumor growth, overall survival, and metastatic dissemination in vivo.

Results:

Radiotherapy and palbociclib employed as standalone agents had partial cytostatic effects in vitro, correlating with suboptimal tumor control in vivo. However, while palbociclib delivered before focal radiotherapy provided minimal benefits as compared with either treatment alone, delivering focal radiotherapy before palbociclib mediated superior therapeutic effects, even in the absence of p53. Such superiority manifested in vitro with enhanced cytostasis and loss of clonogenic potential, as well as in vivo with improved local and systemic tumor control.

Conclusions:

Our preclinical findings demonstrate that radiotherapy delivered before CDK4/6 inhibitors mediates superior antineoplastic effects compared with alternative treatment schedules, calling into question the design of clinical trials administering CDK4/6 inhibitors before radiotherapy in women with ER+ breast cancer.

Introduction

Estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) breast cancer accounts for approximately 70% of all breast cancer cases, de facto representing the most common cause of breast cancer–related death in the United States (1). Indeed, despite the progress achieved over the past decades with screening campaigns and systemic adjuvant therapy, patients with ER+ breast cancer remain at risk for recurrence and death for the rest of their life, with mortality rates of 15%–49% depending on degree of axillary nodal involvement at diagnosis (2). Recently, considerable enthusiasm has been raised by the demonstration that cell-cycle inhibitors targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) increase progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in women with metastatic ER+ breast cancer receiving standard-of-care (SOC) endocrine therapy with aromatase inhibitors (3). Thus, no less than three different CDK4/6 inhibitors, namely, palbociclib (P), abemaciclib, and ribociclib, have been approved in combination with endocrine therapy for the first-line management of women with metastatic ER+ breast cancer (4). Nevertheless, most patients receiving CDK4/6 inhibitors as part of their treatment for metastatic ER+ breast cancer eventually experience disease progression, calling for the exploration of combinatorial regimens that may further extend PFS and OS in this patient population (4).

Focal radiotherapy (RT) has attracted attention as a possible combinatorial partner for CDK4/6 inhibition for multiple reasons. First, radiotherapy has a well-established safety profile and has been consistently employed for palliative purposes in patients with metastatic ER+ breast cancer (5). Second, both CDK4/6 inhibitors and radiotherapy employed at clinically meaningful doses operate (at least in part) as cytostatic therapies, but while the former mediate a robust cell-cycle arrest in the G1-phase that depends on retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) expression (6), the latter generally blocks cell-cycle progression and initiates cell death from the G2–M checkpoint (7). Finally, both focal radiotherapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors mediate immunomodulatory effects that exhibit limited overlap, and hence may synergize in support of local and systemic tumor control (8-10).

Early preclinical experiments testing focal radiotherapy in combination with palbociclib in human glioblastoma or atypical-teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) cell lines maintained in vitro or xenografted into athymic (nu/nu) mice supported the superiority of a therapeutic schedule involving palbociclib administration after radiotherapy completion (RT→P) over a regimen of palbociclib preceding focal radiotherapy (P→RT; ref. 11). At least in part, the superiority of RT→P could be explained by the ability of palbociclib to inhibit the DNA damage response that is initiated in malignant cells by radiotherapy (11). Similar results have been obtained with palbociclib or abemaciclib in human non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and carcinoma cells maintained in vitro or xenografted in athymic mice, especially (but not exclusively) in the context of tumor protein p53 (TP53, best known as p53) expression (12, 13). Moreover, administering CDK4/6 inhibitors before radiotherapy (P→RT) is expected to limit the fraction of malignant cells that are in the G2–M-phase, thus impairing (at least to some degree) the cytotoxic activity of radiotherapy. In line with this notion, the administration of palbociclib before single-dose subtotal body irradiation (SBI) afforded the gastrointestinal tract of tumor-naïve, immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice, with robust radioprotection, de facto limiting the cytotoxic effects of radiotherapy against normal tissues (14). Conversely, gastrointestinal side effects were exacerbated when palbociclib was delivered along with hypofractionated SBI, pointing to elevated cytotoxicity (14).

Apparently at odds with these observations, it has recently been reported that multiple CDK4/6 inhibitors employed at subcytostatic doses radiosensitize human ER+ breast cancer cell lines including MCF7 cells in vitro, and that initiation of radiotherapy (at 2 Gy/fraction over 5 consecutive days) 1 day after palbociclib employed at subclinical doses (25 mg/kg over 6 consecutive days) offers superior OS to highly immunodeficient scid mice bearing MCF7 xenografts as compared with radiotherapy, albeit local disease control appears surprisingly similar (15). While these findings may lend support to testing radiotherapy combined with CDK4/6 inhibitors in patients with metastatic ER+ breast cancer, the proposed therapeutic schedule emerged from preclinical experiments in immunodeficient mice, which are unlikely to mimic the clinical setting. Concerns about the translational value of these findings are particularly relevant in this therapeutic setting because both radiotherapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors have a major influence on anticancer immune responses (8, 16, 17).

Here, we report in vitro findings based on fully cytostatic palbociclib concentrations and human ER+ and ER-negative (ER−) breast cancer lines, as well as in vivo data based on clinically relevant palbociclib doses and three immunocompetent models of breast cancer including a unique immunocompetent mouse model of mammary carcinogenesis that recapitulates key features of human luminal B breast cancer (18), demonstrating that radiotherapy delivered before palbociclib achieves superior efficacy as compared with alternative therapeutic schedules. These preclinical data aim at raising caution on the design of clinical trials administering CDK4/6 inhibitors before radiotherapy in women with ER+ breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals, cell lines, and irradiation

Unless otherwise indicated, chemicals and other reagents were purchased by Millipore Sigma. Human mammary adenocarcinoma MCF7 cells (RRID:CVCL_0031) and MDA-MB-231 (RRID: CVCL_0062) cells, as well as mouse mammary adenocarcinoma TS/A cells (RRID:CVCL_VQ63) and triple-negative breast carcinoma 4T1 cells (RRID:CVCL_0125) were kindly provided by Sandra Demaria (Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY), and routinely maintained at 37° C under 5% CO2, in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 5 mmol/L l-glutamine, 5 mmol/L HEPES buffer, 50 μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin sodium, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, and 50 μg/mL gentamycin. Cells and mice were irradiated with a Small Animal Radiation Research Platform (SARRP, from Xstrahl). All cells were checked for Mycoplasma spp. contamination at least every month by the PCR-based LookOut Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit, and authenticated by STR profiling (a service provided by IDEXX Bioresearch). All cells were used for experimental assessments after two and for no longer than 10 passages after thawing.

Flow cytometry

Cell death was assessed by flow cytometry upon costaining cells with the mitochondrial transmembrane potential-sensitive dye 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide [DiOC6(3), Invitrogen Thermo Fisher Scientific; 40 nmol/L] and propidium iodide (PI; 0.5 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C, as per standard protocols (19). Cell cycle was assessed by flow cytometry upon pulsing living cells with 0.5 μg/mL bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for 2 hours, followed by permeabilization in ethanol overnight at −20° C, resuspension in 0.4 mg/mL pepsin in 0.1 N HCl for 20 minutes at room temperature, incubation with 2 N HCl for 10 minutes at 37°C, and pH neutralization with 0.05 mol/L borate buffer for 5 minutes at room temperature, as described previously (6). Finally, samples were sequentially stained with a BrdU-specific, FITC-conjugated antibody (clone BMC 9318, Roche Diagnostics) in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature and 50 μg/mL PI plus 220 μg/mL RNase A in PBS supplemented with 0.1% BSA for 30 minutes at 37° C. Flow cytometry samples were acquired on a MACSQuant Analyzer 10 (Miltenyi Biotec) and preliminary data analysis was performed with FlowJo v. 10.6 (FlowJo LLC, RRID:SCR_008520).

Clonogenic assays

MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells optionally exposed to a single radiotherapy fraction of 1–5 Gy, 100 nmol/L palbociclib, or their combination were reseeded in 6-well plates at 50–400 cells per well, cultured in control conditions for 7–14 days, and stained with crystal violet (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to conventional procedures (20). Plates were imaged for red fluorescence (crystal violet has absorption/emission peaks at 595/635 nm, respectively) on a C600 Gel Doc and Western Imaging System (Azure Biosystems) and colonies automatically counted on Photoshop 2020 (Adobe, RRID:SCR_014199). Surviving fractions depict the ratio between number of colonies observed and number of cells seeded, upon normalization to plating efficiency (number of colonies observed/number of cells seeded in control conditions). Clonogenic survival curves, each normalized to its specific control, were fitted to the data using the linear-quadratic model. Sensitizer enhancement ratios (SER) for surviving fractions of 0.5 and 0.2 were calculated from linear quadratic models as SER = radiotherapy dose causing 50% (80%) loss in clonogenic survival per se/radiotherapy dose causing 50% (80%) loss in clonogenic survival when combined with palbociclib, as described previously (21).

In vivo experiments

Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions, and experiments followed the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medical College (New York, NY; no. 2019–2022). To obtain TS/A and 4T1 mammary tumors, 0.1 × 106 wild-type TS/A cells or 0.55 × 105 wild-type 4T1 cells were inoculated subcutaneously to female 4- to 9-week-old BALB/cAnN mice (Taconic Biosciences, RRID: IMSR_NIG:222), respectively, and allowed to grow until a surface area of 20–30 mm2 (day 0, d0). To obtain M/D-driven mammary tumors, 6- to 9-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (Taconic Bioscience, RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664) were implanted subcutaneously with 50 mg slow-release (90 days) medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, M) pellets (Innovative Research of America) followed by oral administration of 1 mg 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA, D) in 200 μL corn oil once a week on weeks 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 after implantation of the MPA pellet (18). Mice were then routinely monitored for the emergence of neoplastic lesions along the mammary lines, which were allowed to reach a surface area of 50–80 mm2 (d0). On d0, mice bearing TS/A, 4T1 or M/D-driven mammary tumors were randomly allocated to five treatment arms: (i) no treatment; (ii) focal radiotherapy (for TS/A tumors: three fractions of 6 Gy each on d0–d2; for M/D-driven tumors: three fractions of 10 Gy each on d0–d2; for 4T1 tumors: one fraction of 12 Gy on d0); (iii) oral palbociclib (MedChem Express; 150 mg/kg in 50 mmol/L sodium lactate pH 4.0, on d0–d13); (iv) focal radiotherapy (on d0–d2 for TS/A and M/D-driven tumors; on d0 for 4T1 tumors) followed by oral palbociclib (on d3–d16 for TS/A and M/D-driven tumors; on d1–d14 for 4T1 tumors); or (v) oral palbociclib (on d0–d13) followed by focal radiotherapy (on d14–d16 for TS/A and M/D-driven tumors; on d14 for 4T1 tumors). Mice were routinely monitored for signs of toxicity (weight loss, anorexia, hunched posture), growth of the primary (target) lesion (by a common caliper) as well as emergence and growth of secondary tumors (in the M/D-driven model; ref. 18). Palbociclib dosage was reduced to 100 mg/kg for individual mice manifesting signs of systemic toxicity. Tumor surface was calculated as the area of an ellipse (A = longest diameter × shortest diameter × π/4), as per common procedures (18). TS/A-bearing mice were euthanized when tumors reached 130 mm2 surface area or at d35, in the latter case coupled to survival projection until d40 based on exponential regression fit on individual growth curves. Mice bearing M/D-driven tumors were euthanized when lesions reached 180–200 mm2 cumulative surface area. 4T1-bearing mice were euthanized at d21 (when untreated mice exhibited respiratory distress associated with pulmonary disease progression). Metastatic 4T1 cell dissemination to the lung surface was evaluated by three independent, blinded operators (A. Buqué, T. Yamazaki, N. Bloy), using a DM-143 digital stereo microscope (Motic) upon lung fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, as described previously (22).

Statistical analysis

Data management, analysis, and graphing was performed with Prism v. 8.4 (GraphPad, RRID:SCR_002798) or Excel 265 ProPlus (Microsoft, RRID:SCR_016137). Unless otherwise specified, in vitro results were obtained from at least three independent biological samples collected over at least two independent experiments. Cell death, clonogenic survival, cell cycle, and metastatic dissemination data were assessed for statistical significance by paired or unpaired one-way ANOVA plus Fisher LSD test. Tumor growth was assessed for statistical significance by repeated measures (RM) one-way ANOVA plus Geisser–Greenhouse correction and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test with individual variances computed for each comparison. Overall survival was assessed for statistical significance by the Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test.

Results

Radiotherapy followed by palbociclib at fully cytostatic doses mediates superior cytostatic effects against cultured breast cancer cells

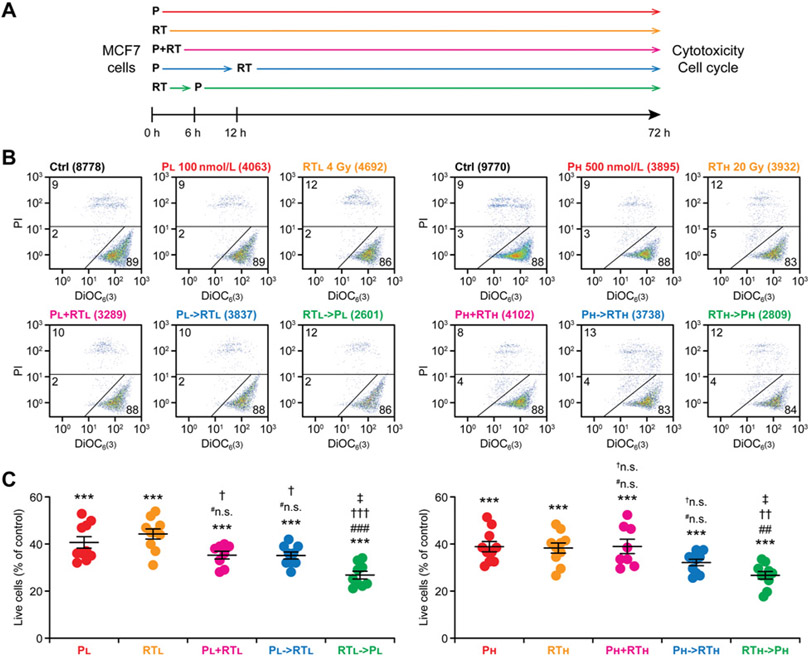

Inspired by previous findings in glioblastoma and ATRT models (11), we initially set out to confirm the ability of radiotherapy and CDK4/6 inhibition with palbociclib to cooperate at arresting the cell cycle of human RB1- and p53-competent ER+ breast cancer MCF7 cells (23), with a specific focus on treatment sequencing (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous sensitivity data (24), single-agent palbociclib (at both 100 and 500 nmol/L, with little difference across doses) caused a robust cytostatic effect amongst cultured MCF7 cells, but minimal signs of overt cytotoxicity, as assessed by flow cytometry upon costaining with DiOC6(3), which marks cells with functional mitochondria (i.e., healthy cells), and PI, which only enters cells with permeabilized plasma membranes (i.e., dead cells; ref. 20; Fig. 1B and C). Similarly, radiotherapy delivered in single fraction of 4 or 20 Gy strongly inhibited the growth of MCF7 cells, yet failed to elicit a major cytotoxic response that would manifest within 72 hours from irradiation (Fig. 1B and C). Importantly, while irradiating MCF7 cells 12 hours after palbociclib administration virtually failed to enhance growth inhibition as compared with palbociclib or radiotherapy, robust additive cytostasis emerged when palbociclib was administered 6 hours after irradiation (Fig. 1B and C). Such a robust additivity could be documented at two different palbociclib and radiotherapy doses (Fig. 1B and C), whereas the concurrent administration of palbociclib and radiotherapy (P+RT) mostly failed to improve the cytostatic effects of either drug employed as standalone agent (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1.

Radiotherapy followed by palbociclib mediates robust cytostatic effects against human ER+ breast cancer cells. A, Experimental setting. P, palbociclib; RT, radiotherapy. B and C, MCF7 cells were cultured in control conditions or exposed to P or a single radiotherapy fraction in the indicated doses and combinations, as schematized in A, followed by the flow cytometry-assisted quantification of residual cell number, mitochondrial depolarization, and plasma membrane rupture. Representative dot plots (B) and quantitative data (C) are reported. In B, total number of cells and percentage of cells in each quadrant are indicated. Results are means ± SEM plus individual data points from n = 8–10 independent biological samples from 4–5 independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed with paired one-way ANOVA plus Fisher LSD test. ***, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells maintained in control conditions; #n.s., not significant; ##, P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with the same P dose; †n.s., not significant; †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01; †††, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated the same radiotherapy dose; ‡, P < 0.05, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with the same doses of P→RT.

Human triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) MDA-MB-231 cells bear TP53 mutations and hence (i) are remarkably less sensitive to palbociclib than MCF7 cells (24) and (ii) are expected to enable limited cooperativity between palbociclib and radiotherapy, at least based on previous work with p53-competent versus p53-incompetent human NSCLC and colorectal cancer cell lines (12, 13). Indeed, in MDA-MB-231 cells, the RT→P schedule was superior to either treatment alone only in the low-dose setting, whereas administering 500 nmol/L palbociclib after 20 Gy radiotherapy increased the antiproliferative effects of the former, but not the latter (Supplementary Fig. 1A-C). Nevertheless, P→RT consistently exhibited inferior cytostatic effects as compared to RT→P (in the low-dose setting) or radiotherapy alone and RT→P (in the high-dose setting) also in MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1A-C).

These findings demonstrate that RT→P is superior to P→RT at mediating short-term cytostatic effects in two different models of human breast cancer, with limited impact from p53 competence.

Cell-cycle distribution in breast cancer cells exposed to radiotherapy and palbociclib combinations

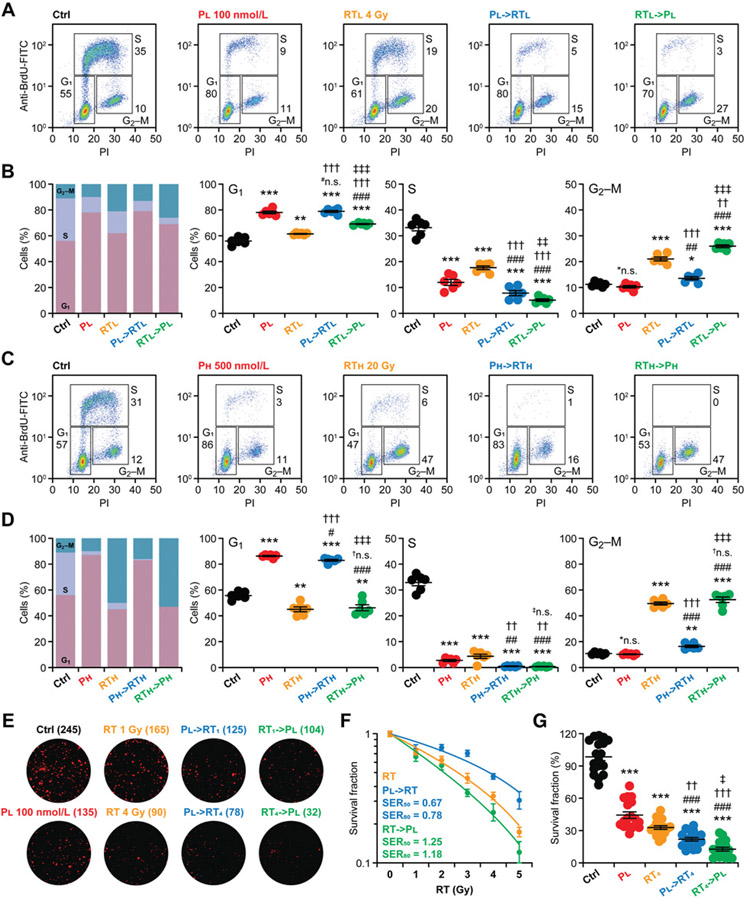

To obtain a more granular view of cell-cycle distribution in breast cancer cells responding to palbociclib, radiotherapy or their sequential combination (Fig. 1A), we pulsed MCF7 cells engaged in active DNA replication with the synthetic thymidine analogue BrdU for 2 hours, followed by the flow cytometry–assisted detection of BrdU uptake (6). In this setting, PI is harnessed as a marker of DNA content upon artificial plasma membrane permeabilization, ultimately enabling the clear discrimination of cells in the G1, S, and G2-M-phase of the cell cycle (6). As expected previously (24), 100 nmol/L palbociclib and 4 Gy radiotherapy employed as single agents provoked a cell-cycle arrest mostly in the G1 and G2–M, respectively, which in both cases was coupled with a significant reduction in the percentage of cells in the S-phase (Fig. 2A and B). While radiotherapy delivered 12 hours after palbociclib further reduced the percentage of MCF7 cells in the S-phase (Fig. 2A and B), such an additive effect was more robust when radiotherapy was delivered 6 hours before palbociclib (Fig. 2A and B). Of note, the percentage of MCF7 cells blocked in G2–M was significantly higher upon RT→P than upon P→RT (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting the preferential ability of the former schedule to engage the G2–M checkpoint. At least theoretically, this may also be beneficial because neoplastic cells blocked in G1 sometimes survive for extended periods as they undergo cellular senescence—a nonproliferative, metabolically active state that (at least in some settings) support tumor progression (25). However, whether arresting cancer cells in G2–M versus G1 actually offers a therapeutic advantage remains a matter of debate.

Figure 2.

Superior short- and long-term cell-cycle control by radiotherapy followed palbociclib in human ER+ breast cancer cells. A-D, MCF7 cells were cultured in control conditions or exposed to palbociclib (P) or a single radiotherapy (RT) fraction in the indicated doses and sequential combinations, as depicted in Fig. 1A, followed by the flow cytometry-assisted quantification of cell-cycle distribution. Representative dot plots (A and C) and quantitative data (B and D) are reported. In A and C, the percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. Results are mean cumulative cell-cycle distribution as well as means ± SEM plus individual data points for each cell-cycle phase from n = 6 independent biological samples collected over three independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed with paired one-way ANOVA plus Fisher LSD test. *n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells maintained in control conditions; #n.s., not significant; #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with P alone; †n.s., not significant; ††, P < 0.01; †††, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with radiotherapy alone; ‡n.s., not significant; ‡‡, P < 0.01; ‡‡‡, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with the same doses of P→RT. Please note that control samples in B and D are the same. E-G, Residual clonogenic potential of MCF7 cells optionally treated with the indicated radiotherapy dose alone or in sequential combination with 100 nmol/L palbociclib and then allowed to form colonies for 14 days. Representative images (E) and quantitative data (F and G) are reported. In E and F, number of colonies and SERs for 50% and 80% efficacy are indicated, respectively. Results are means ± SEM normalized to untreated MCF7 cells (F, radiotherapy; G) or MCF7 cells treated with P alone (F, P→RT, RT→P) optionally fitted to the linear-quadratic model (F) from n = 12–18 independent biological samples collected over 2–3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed with unpaired one-way ANOVA plus Fisher LSD test. ***, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells maintained in control conditions; ###, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with P alone;‡‡, P < 0.01; ‡‡, P < 0.001, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with radiotherapy alone; ‡, P < 0.05, as compared with MCF7 cells treated with the same doses of P→RT.

At higher palbociclib (500 nmol/L) and radiotherapy (20 Gy) doses, the cytostatic effects of either agent employed as standalone therapeutic intervention were very robust, invariably limiting the percentage of MCF7 cells in the S-phase below 6%–8% (Fig. 2C and D). In this setting, the additive effects of P→RT versus RT→P on the percentage of MCF7 cells in the S-phase were virtually comparable (and provided limited, although statistically significant, benefits over each agent alone), but the latter approach remained superior to the former at causing an overt blockage at the G2–M checkpoint (Fig. 2C and D). Although of reduced magnitude (especially at low palbociclib and radiotherapy doses, as expected by the limited sensitivity of MDA-MB-231 cells to palbociclib), similar findings could be also documented in MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A-D). The fact that radiotherapy and palbociclib exhibited (at least some) cooperativity in controlling the progression of MDA-MB-231 cells in the cell cycle suggests that factors other than p53 competence may influence the ability of these two agents to mediate additive/synergistic effects. In support ofthis notion, previous work reported strong therapeutic interactions between radiotherapy and palbociclib in human NSCLC H1975 cells (which bear TP53 mutations), which is at odds with other p53-incompetent NSCLC cells (13).

To gain additional insights into the long-term cytostatic anticancer activity of RT→P versus P→RT, we optionally exposed MCF7 cells to radiotherapy in single doses of 1–5 Gy, alone or in sequential combination with 100 nmol/L palbociclib, and assessed residual clonogenic survival 14 days later. As expected based on the half-life of palbociclib in the culture medium (~48 hours) and radiotherapy doses (15), both palbociclib and radiotherapy employed as standalone cytostatic agents inhibited colony formation by MCF7 cells in a relatively suboptimal manner (Fig. 2E-G). Consistent with recent findings (15) and our cell-cycle data (Fig. 2A-D), P→RT enhanced the loss of clonogenic potential imposed by radiotherapy alone over the range of doses tested (Fig. 2E-G). However, the cumulative effects of P→RT were subadditive, as demonstrated by SERs <1, meaning that P→RT had inferior activity as compared to what was expected if each of the agents had comparable effects when used alone versus combined (Fig. 2E and F). Conversely, the RT→P schedule not only had a more profound impact on clonogenic survival than either agent alone and P→RT, but also exhibited supraadditive cooperativity (SER>1), meaning that RT→P had superior activity as compared with what was expected if each of the agents had comparable effects when used alone versus combined (Fig. 2E and F). Despite their TP53 mutational status, similar findings were obtained with MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2E-G).

Altogether, these findings suggest that RT→P enable a superior cell-cycle control in cultured human ER+ and ER− breast cancer cells in a manner that does not entirely depend on p53 competence.

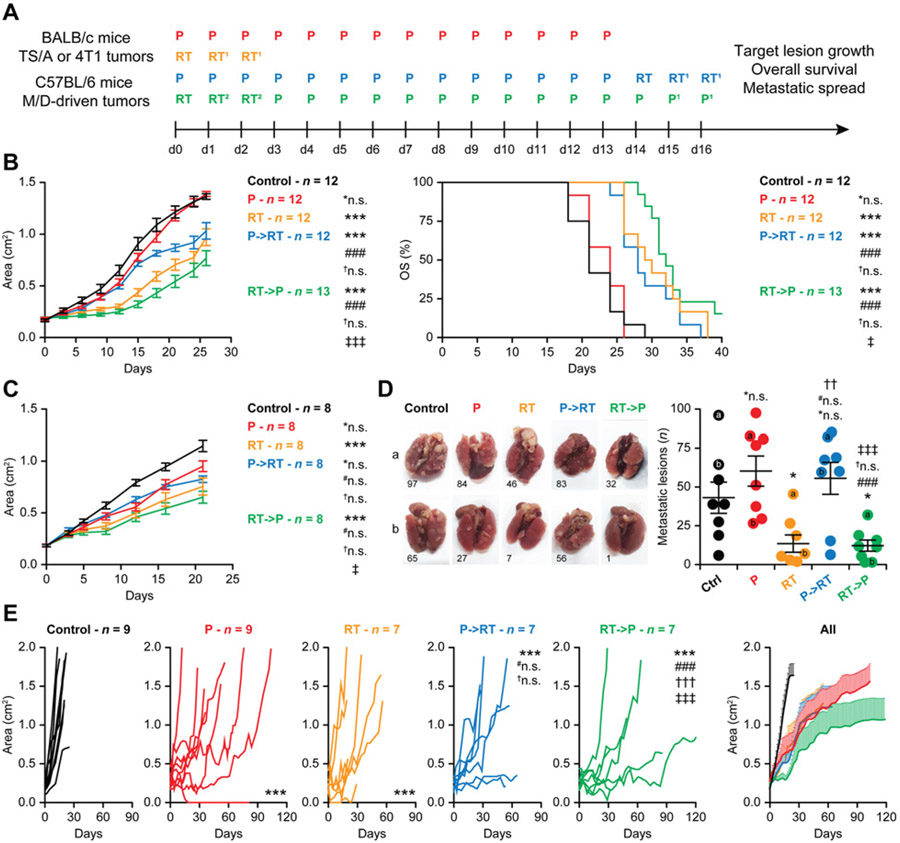

Focal radiotherapy followed by palbociclib at clinically relevant doses mediates superior efficacy in mouse models of HR+ breast cancer

Recognizing the major limitations that affect in vitro tumor models especially in the era of modern immuno-oncology (26), we investigated the therapeutic activity of palbociclib, radiotherapy, and their sequential combination in immunocompetent BALB/c mice bearing syngeneic TS/A mammary adenocarcinomas subcutaneously, again focusing on treatment schedule (Fig. 3A). In this p53-incompetent model (27), radiotherapy delivered in three consecutive fractions of 6 Gy each (total dose 18 Gy) controlled local disease progression, while palbociclib monotherapy (in the clinically relevant dose of 150 mg/kg for 14 consecutive days starting at tumor detection) had virtually no effects (Fig. 3B). The effects of palbociclib on local disease progression were ameliorated by the subsequent delivery of radiotherapy (Fig. 3B). However, the best local control of subcutaneous TS/A tumors was achieved by RT→P, which was superior to all other regimens in this respect (Fig. 3B). In line with these data, palbociclib monotherapy failed to prolong the OS of TS/A-bearing mice, and while both radiotherapy and P→RT had partial OS-extending effects, RT→P was associated with the largest OS extension in this model (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Radiotherapy followed by palbociclib enables superior local control of endogenous ER+ mammary tumors developing in immunocompetent mice. A, Experimental setting. P, palbociclib; RT, radiotherapy. 1Only for TS/A and M/D-driven tumors; 2replaced by palbociclib for 4T1 tumors. B, Female BALB/c mice bearing palpable TS/Amammary carcinomas were randomly allocated to no treatment or to palbociclib (150 mg/kg per dose), radiotherapy (6Gy per fraction), or their combination as illustrated in A, and monitored over time for tumor growth and survival. Results are mean tumor areas ± SEM from the indicated number of mice per group and OS, as obtained in two independent experiments. Statistical assessments for tumor growth were performed with RM one-way ANOVA plus Geisser–Greenhouse and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical assessments forOSwere performed with the Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test. *n.s., not significant; ***, P < 0.001, as compared with untreated mice; ###, P < 0.001, as compared with P-treated mice; †n.s., not significant, as compared with radiotherapy-treated mice; ‡, P < 0.05; ‡‡‡, P < 0.001, as compared with mice treated with P→RT. C and D, Female BALB/c mice bearing palpable 4T1 mammary carcinomas were randomly allocated to no treatment or to palbociclib (150 mg/kg per dose), radiotherapy (12 Gy in a single fraction), or their combination as illustrated in A, and monitored over time for tumor growth. Results are mean tumor areas ± SEM from the indicated number of mice per group (C), or mean number of surface lung metastases on d21 ± SEM and individual data points (inclusive of representative images; D). Statistical assessments for tumor growth were performed with RM one-way ANOVA plus Geisser–Greenhouse and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical assessments for metastatic dissemination were performed with paired one-way ANOVA plus Fisher LSD test, respectively. *n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001, as compared with untreated mice; #n.s., not significant; ###, P < 0.001, as compared with P-treated mice; †n.s., not significant; †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01, as compared with radiotherapy-treated mice; ‡, P < 0.05; ‡‡‡, P < 0.001, as compared with mice treated with P→RT. E, Female C57BL/6 mice bearing palpableM/D-driven carcinomas were randomly allocated to no treatment or to P (150 mg/kg per dose), radiotherapy (10 Gy per fraction), or their combination as illustrated in A, and monitored over time for the growth of the target lesion. Results are individual growth curves and mean tumor areas ± SEM from the indicated number of mice per group. Statistical assessments for tumor growth were performed with RM one-way ANOVA plus Geisser–Greenhouse and Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. ***, P < 0.001, as compared with untreated mice; #n.s., not significant; ###, P < 0.001, as compared with P-treated mice; †n.s., not significant; †††, P < 0.001, as compared with radiotherapy-treated mice; ‡‡‡, P < 0.001, as compared with mice treated with P→RT.

To obtain additional insights into the therapeutic activity of palbociclib, radiotherapy, and their sequential combination in immunocompetent breast cancer models, we focused on mouse 4T1 mammary carcinomas, a widely employed model of metastatic TNBC (28). While palbociclib monotherapy had marginal impact on the growth of subcutaneous 4T1 tumors, a single radiotherapy fraction of 12 Gy had robust effects on primary disease progression (Fig. 3C). RT→P offered a minimal advantage on local disease control over radiotherapy alone (Fig. 3C), potentially linked to the fact that 4T1 cells are considerably more aggressive than TS/A cells and lack p53 expression (29). However, P→RT not only failed to ameliorate the marginal therapeutic activity of palbociclib alone, but it was also considerably inferior to RT→P at inhibiting the growth of subcutaneous 4T1 lesions (Fig. 3C). Consistent with these findings, RT alone and RT→P were the only regimens to significantly control the development of 4T1 lung metastases, with virtually no systemic disease control from palbociclib monotherapy or P→RT (Fig. 3D). As in our experimental conditions, the metastatic dissemination of subcutaneously implanted 4T1 cells occurs prior to treatment initiation (22, 29); these data suggest that RT→P (but not P→RT) may engage a tumor-targeting immune response with systemic outreach.

Although advantageous as compared with human cancer cell lines xenografted in immunodeficient hosts, subcutaneous tumors established in immunocompetent mice with syngeneic cancer cell lines fail to recapitulate early oncogenesis as these cells have already evaded immune recognition in the original host (26). Moreover, both TS/A cells and 4T1 are p53-incompetent (27, 29), which has been associated with limited cooperativity between radiotherapy and palbociclib in some tumor models (12, 13). Thus, we set to test the therapeutic activity of palbociclib, radiotherapy, and their sequential combination (Fig. 3A) in an endogenous mouse model of mammary carcinogenesis driven by a synthetic progestin, that is, MPA (M) and a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, that is, DMBA (D), which often exhibit wild-type Trp53 status (30). Besides being often p53 competent as most human HR+ breast cancer (31), M/D-driven mammary tumors established in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice recapitulate several immunobiological features of human luminal B breast cancer, including transcriptional profile, sensitivity to hormonal interventions, and detrimental dietary habits (e.g., a high-fat diet), scarce infiltration by immune cells, as well as limited responsiveness to immune checkpoint blockade (18). As such, M/D-driven mammary tumors evolving in immunocompetent mice stand out as a preferential and highly translational platform for the preclinical development of therapeutic regimens for ER+ breast cancer.

In line with previous findings (18), untreated M/D-driven tumors evolved rapidly, which required euthanasia owing to excessive disease burden within the first 30 days from tumor detection in all mice (Fig. 3E). Conversely, radiotherapy delivered in three consecutive fractions of 10 Gy each (which is clinically relevant for the management of metastatic ER+ breast cancer) mediated robust disease control as it significantly delayed the growth of the primary (irradiated) tumor (Fig. 3E). Oral palbociclib had even more robust therapeutic effects (Fig. 3E). Moreover, while the administration of radiotherapy after completion of palbociclib treatment completely failed to ameliorate the therapeutic activity of the latter, RT→P exerted superior efficacy as compared with all other treatments (Fig. 3E).

Although this latter experimental context is not appropriate to assess OS (as over time mice develop tumors other than the one allocated to focal radiotherapy or emerging after the cessation of palbociclib; ref. 18), altogether our findings support the administration of radiotherapy before, not after, palbociclib in clinical trials testing such regimens in women with ER+ breast cancer.

Discussion

Considerable efforts are being devoted to the identification of safe and effective combinatorial partners for CDK4/6 inhibitors, not only for the management of metastatic ER+ breast cancer (4), but also in the context of numerous clinical trials that are currently investigating the therapeutic profile of CDK4/6 inhibitors in patients with hematologic malignancies including mantle cell lymphoma (32). Appropriate dosing and therapeutic schedules are obviously critical components of the overall probability for phase II–III clinical trials to meet their endpoints and thus be deemed successful (33). Nonetheless, while doses are generally developed in preclinical models and early-phase clinical studies toward an optimal compromise between safety and activity, hundreds of trials testing combinatorial anticancer regimens are being initiated with little, if any, preclinical support on treatment sequencing.

To enable the optimal translation of preclinical data to the clinic, we embarked in the systematic preclinical assessment of treatment sequencing with the specific aim of informing the design of a randomized phase II clinical trial testing the added therapeutic value of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) in the context of SOC palbociclib/letrozole therapy in women with ER+ metastatic breast cancer. Our findings demonstrated a clear superiority for RT→P over P→RT, not only in terms of cell-cycle blockage in vitro (Figs. 1 and 2), but also in terms of disease control in vivo (Fig. 3). Apparently at odds with previous data from human NSCLC and colorectal cancer cells (12, 13), the cooperativity between radiotherapy and palbociclib was not always compromised in p53-incompetent breast cancer models (Figs. 1-3), pointing to the existence of hitherto unidentified genetic, epigenetic, or metabolic features underlying this therapeutic interaction. Moreover, the systemic disease control achieved by RT→P (but not P→RT) in an immunocompetent model of TNBC that disseminates to the lungs prior to treatment (refs. 22 and 29; Fig. 3) suggests that palbociclib delivered before radiotherapy may compromise the initiation of an anticancer immune response with systemic outreach (8, 17). However, it remains possible that the cooperativity at systemic disease control enabled by RT→P (but not P→RT) may reflect a superior control of the primary tumor, as in our study radiotherapy alone also limited the number of lung metastases in 4T1-bearing mice, which is at odds with previous observations (22, 34). Thus, further work is required to elucidate the immunological pathways elicited by RT→P, an aspect that we are currently investigating in preparation of another report. Moreover, it will be important to interrogate the added therapeutic and/or immunologic value of hormonotherapy. This is particularly relevant as CDK4/6 inhibitors are invariably administered to patients with metastatic ER+ breast cancer in the context of letrozole- or fulvestrant-based endocrine therapy, which appear to be required for optimal therapeutic outcomes (3, 35). Irrespective of these and other unresolved questions, our data inspired the design of the CIMER (Combined IMmune Effects of therapies in metastatic ER+ breast cancer) trial (NCT04563507), enrolling women with newly diagnosed oligometastatic ER+ breast cancer. The CIMER trial randomizes patients to either SOC palbociclib/letrozole or SOC palbociclib/letrozole preceded by SBRT to each metastatic lesion, reflecting the optimal treatment schedule we demonstrated in preclinical models of the disease. In summary, our findings and the aforementioned considerations are meant to raise caution on the design of clinical trials administering CDK4/6 inhibitors before radiotherapy in women with ER+ breast cancer (and potentially other tumor types).

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Our data from various mouse models of estrogen receptor–positive (ER+) and –negative (ER−) breast cancer, including an immunocompetent model that recapitulates key features of luminal B breast cancer in women, argue against recent findings suggesting that CDK4/6 inhibitors can be used for radiosensitization and thus should be delivered before radiotherapy in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted with Sandra Demaria from the Department of Radiation Oncology of Weill Cornell Medicine (New York, NY) for the kind gift of MCF7, MDA-MB-231, TS/A, and 4T1 cells, and to Jeffrey Kraynak from the Weill Cornell Medicine Radiation Biology Core Facility (established with support from an NIH/NCI Small Instrumentation Grant to SCF #S10-RR027619-01) for help with irradiation procedures. G. Petroni, S.C. Formenti, and L. Galluzzi are supported by the 2019 Laura Ziskin Prize in Translational Research (#ZP-6177) from the Stand Up to Cancer initiative. A. Buqué, S.C. Formenti, and L. Galluzzi are supported by a Breakthrough Level 2 grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, Breast Cancer Research Program (#BC180476P1). S. Chen-Kiang and L. Galluzzi are supported by a Mantle Cell Lymphoma Research Initiative grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (#MCL7001–18). S. Chen-Kiang is further supported by a P01 grant (#CA214274) and an R01 grant (#CA188794) from the NIH/NCI. L. Galluzzi is further supported by a startup grant from the Department of Radiation Oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine (New York, NY), by a Rapid Response Grant from the Functional Genomics Initiative (New York, NY), by industrial collaborations with Lytix (Oslo, Norway) and Phosplatin (New York, NY), and by donations from Phosplatin (New York, NY), the Luke Heller TECPR2 Foundation (Boston, MA), and SOTIO a.s. (Prague, Czech Republic).

Footnotes

Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69: 7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, Davies C, Taylor C, McGale P,et al. 20-Year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1836–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, Fasching PA, De Laurentiis M, Im SA, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:514–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Leary B, Finn RS, Turner NC. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:417–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox JA, Swanson TA. Current modalities of accelerated partial breast irradiation. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:344–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiron D, Martin P, Di Liberto M, Huang X, Ely S, Lannutti BJ, et al. Induction of prolonged early G1 arrest by CDK4/CDK6 inhibition reprograms lymphoma cells for durable PI3Kdelta inhibition through PIK3IP1. Cell Cycle 2013;12: 1892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobrich M, Jeggo PA. The impact of a negligent G2–M checkpoint on genomic instability and cancer induction. Nat Rev Cancer 2007;7:861–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golden EB, Marciscano AE, Formenti SC. Radiation therapy and the in situ vaccination approach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;108:891–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ameratunga M, Kipps E, Okines AFC, Lopez JS. To cycle or fight-CDK4/6 inhibitors at the crossroads of anticancer immunity. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25: 21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamazaki T, Kirchmair A, Sato A, Buque A, Rybstein M, Petroni G, et al. Mitochondrial DNA drives abscopal responses to radiation that are inhibited by autophagy. Nat Immunol 2020;21:1160–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashizume R, Zhang A, Mueller S, Prados MD, Lulla RR, Goldman S, et al. Inhibition of DNA damage repair by the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib delays irradiated intracranial atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor and glioblastoma xenograft regrowth. Neuro Oncol 2016;18:1519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Aroca DM, Roche O, Sabater S, Pascual-Serra R, Ortega-Muelas M, Sanchez Perez I, et al. P53 pathway is a major determinant in the radiosensitizing effect of palbociclib: implication in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett 2019;451:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naz S, Sowers A, Choudhuri R, Wissler M, Gamson J, Mathias A, et al. Abemaciclib, a selective CDK4/6 inhibitor, enhances the radiosensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24: 3994–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CL, Oh P, Xu ES, Ma Y, Kim Y, Daniel AR, et al. Blocking cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 during single dose versus fractionated radiation therapy leads to opposite effects on acute gastrointestinal toxicity in mice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;102:1569–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pesch AM, Hirsh NH, Chandler BC, Michmerhuizen AR, Ritter CL, Androsiglio MP, et al. Short-term CDK4/6 inhibition radiosensitizes estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:6568–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Vitale I, Harrington KJ, Melero I, Galluzzi L. Immunological impact of cell death signaling driven by radiation on the tumor micro-environment. Nat Immunol 2020;21:120–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petroni G, Formenti SC, Chen-Kiang S, Galluzzi L. Immunomodulation by anticancer cell cycle inhibitors. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:669–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buque A, Bloy N, Perez-Lanzon M, Iribarren K, Humeau J, Pol JG, et al. Immunoprophylactic and immunotherapeutic control of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun 2020;11:3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatsuno K, Yamazaki T, Hanlon D, Han P, Robinson E, Sobolev O, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy induces bona fide immunogenic cell death. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Buque A, Hensler M, Chen J, Bloy N, Petroni G, et al. Apoptotic caspases inhibit abscopal responses to radiation and identify a new prognostic biomarker for breast cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2019;8: e1655964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naumann P, Liermann J, Fortunato F, Schmid TE, Weber KJ, Debus J, et al. Sulforaphane enhances irradiation effects in terms of perturbed cell cycle progression and increased DNA damage in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilones KA, Hensler M, Daviaud C, Kraynak J, Fucikova J, Galluzzi L, et al. Converging focal radiation and immunotherapy in a preclinical model of triple negative breast cancer: contribution of VISTA blockade. Oncoimmunology 2020;9:1830524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kao J, Salari K, Bocanegra M, Choi YL, Girard L, Gandhi J, et al. Molecular profiling ofbreast cancer cell lines defines relevant tumor models and provides a resource for cancer gene discovery. PLoS One 2009;4:e6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn RS, Dering J, Conklin D, Kalous O, Cohen DJ, Desai AJ, et al. PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res 2009;11:R77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B, Kohli J, Demaria M. Senescent cells in cancer therapy: friends or foes? Trends Cancer 2020;6:838–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zitvogel L, Pitt JM, Daillere R, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Mouse models in oncoimmunology. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:759–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Giovanni C, Nicoletti G, Landuzzi L, Palladini A, Lollini PL, Nanni P. Bioprofiling TS/A murine mammary cancer for a functional precision experimental model. Cancers 2019;11:1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosely SI, Prime JE, Sainson RC, Koopmann JO, Wang DY, Greenawalt DM, et al. Rational selection of syngeneic preclinical tumor models for immunotherapeutic drug discovery. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aslakson CJ, Miller FR. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res 1992;52:1399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abba MC, Zhong Y, Lee J, Kil H, Lu Y, Takata Y, et al. DMBA induced mouse mammary tumors display high incidence of activating Pik3caH1047 and loss of function Pten mutations. Oncotarget 2016;7:64289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silwal-Pandit L, Vollan HK, Chin SF, Rueda OM, McKinney S, Osako T, et al. TP53 mutation spectrum in breast cancer is subtype specific and has distinct prognostic relevance. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:3569–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin P, Bartlett NL, Blum KA, Park S, Maddocks K, Ruan J, et al. A phase 1 trial of ibrutinib plus palbociclib in previously treated mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2019;133:1201–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fogel DB. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: a review. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2018;11:156–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11:728–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, Jones S, Im SA, Gelmon K, et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1925–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.