SUMMARY

Projection neuron subtype identities in the cerebral cortex are established by expressing pan-cortical and subtype-specific effector genes that execute terminal differentiation programs bestowing neurons with a glutamatergic neuron phenotype and subtype-specific morphology, physiology, and axonal projections. Whether pan-cortical glutamatergic and subtype-specific characteristics are regulated by the same genes or controlled by distinct programs remains largely unknown. Here, we show that FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional repressor, and it regulates subtype-specific identities of both corticothalamic and subcerebral neurons by selectively repressing expression of genes inappropriate for each neuronal subtype. We report that TLE4, specifically expressed in layer 6 corticothalamic neurons, is recruited by FEZF2 to inhibit layer 5 subcerebral neuronal genes. Together with previous studies, our results indicate that a cortical glutamatergic identity is specified by multiple parallel pathways active in progenitor cells, whereas projection neuron subtype-specific identity is achieved through selectively repressing genes associated with alternate identities in differentiating neurons.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

Layer 6 corticothalamic and layer 5 subcerebral projection neurons connect the cerebral cortex to the thalamus and brainstem and spinal cord, respectively. Tsyporin et al. report that the transcription factor FEZF2 specifies the development of these neuronal identities by repressing expression of genes associated with alternate projection neuron subtypes.

INTRODUCTION

Projection neuron subtype identities in the developing cerebral cortex are established by expressing pan-cortical and subtype-specific genes, which execute terminal differentiation programs and bestow neurons with a glutamatergic phenotype and subtype-specific morphology, physiology, and axonal projections. Whether the pan-cortical glutamatergic phenotype and subtype-specific characteristics are regulated by the same genetic program or controlled by distinct genes remains largely unknown. In C. elegans, expression of terminal effector genes is activated by terminal selector genes, which are transcription factors that act in differentiating neurons by binding to common cis-regulatory elements in effector genes and activating their expression (Hobert and Kratsios, 2019). Whether similar mechanisms are utilized in developing mammalian brains is unknown, except the corticospinal motor neurons (CSMNs), a subset of subcerebral projection neurons specified by the transcriptional regulator FEZF2 (Lodato et al., 2014).

Although recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies have allowed classification of neurons into different clusters based on gene expression in individual cells (Tasic et al., 2018), neocortical excitatory neurons can be broadly classified into 3 major subtypes based on where they project axons (Leone et al., 2008). Corticocortical neurons, located in layers 2–6, project axons to the ipsilateral (intracortical) or contralateral (callosal) cortex. The subcerebral neurons projecting to the thalamus (corticothalamic neurons) mostly reside in layer 6, whereas the subcerebral neurons projecting to the midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord are confined to layer 5B (O’Leary and Koester, 1993). Determining the molecular mechanisms underlying the differentiation of these neuronal subtypes is essential for understanding the regulatory logic of cell fate specification in the neocortex.

Prior studies have identified several genes that broadly specify the identities of cortical projection neuron subtypes and revealed that the development of these subtypes depends on a network of transcription factors that cross-inhibit one another’s expression. The zinc-finger transcription factor Fezf2 is expressed in deep-layer neurons. It promotes a subcerebral neuronal identity and suppresses expression of subtype-determining genes for corticothalamic (Tbr1) and callosal (Satb2) neurons (Chen et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2008; Molyneaux et al., 2005). Bcl11b, also known as Ctip2, encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor expressed at high levels in layer 5 subcerebral neurons and at low levels in layer 6 corticothalamic neurons (McKenna et al., 2011). It regulates extension and fasciculation of subcerebral axons (Arlotta et al., 2005). Tbr1 and Sox5 are both expressed at high levels in corticothalamic projection neurons. They promote a corticothalamic neuronal fate and directly repress Fezf2 expression and subcerebral identity in layer 6 neurons (Han et al., 2011; Kwan et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2008; McKenna et al., 2011). Satb2 was initially reported to be specifically expressed in callosal neurons, where it promotes a callosal neuron identity by repressing genes, including Bcl11b, that are essential for subcerebral axon development (Alcamo et al., 2008; Britanova et al., 2008). Recent studies have shown that Satb2 is also dynamically expressed in subcerebral neurons and is required for their fate specification (Leone et al., 2015; McKenna et al., 2015).

Despite the identification of these critical transcription factors, the molecular logic for cortical neuron subtype specification remains elusive. Fezf2 has been the prototypic transcription factor for studying this process in subcerebral neurons. A recent study reported that Fezf2 directly activates the expression of genes conferring glutamatergic and subcerebral neuronal identity and represses genes associated with GABAergic and callosal neuron phenotypes, suggesting that, similar to C. elegans neurons (Hobert and Kratsios, 2019), the subtype identities of cortical excitatory neurons are specified by terminal selector genes (Lodato et al., 2014). However, the ability of Fezf2 to directly activate the expression of terminal effector genes has not been rigorously tested. Fezf2 is expressed in both radial glial cells (RGCs) and in postmitotic neurons (Chen et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2008; Guo et al., 2013; Molyneaux et al., 2005), and it is unclear whether Fezf2 is required in RGCs or in newly generated neurons to specify a subcerebral neuronal fate. The N-terminal of the FEZF2 protein contains an engrailed homology domain (EH1 domain), which is known to recruit the transducin-like enhancer of split (TLE) family transcriptional co-repressors (Hashimoto et al., 2000). It remains to be determined whether FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional repressor, an activator, or both during cortical development. Finally, previous studies and recent scRNA-seq analyses revealed that, in addition to subcerebral neurons, Fezf2 is expressed in corticothalamic and deep-layer callosal neurons (Clare et al., 2017; Molyneaux et al., 2007; Tantirigama et al., 2016; Tasic et al., 2018). If Fezf2 is the terminal selector gene for subcerebral neurons, what is the function of Fezf2 in these other neuronal subtypes?

Members of the TLE family are co-repressors that are not capable of binding DNA, but instead interact with diverse sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors and repress transcription of downstream genes (Jennings and Ish-Horowicz, 2008; Turki-Judeh and Courey, 2012). TLE proteins critically regulate a wide range of organogenesis, including neurogenesis, osteogenesis, and hematopoiesis (Agarwal et al., 2015; Xing et al., 2018). One class of proteins that recruit TLEs are the homeodomain family of transcription factors, through the specific interaction between the EH1 motif of the homeodomain proteins and the WD40 repeats of the TLEs. This interaction is essential for NKX2.2, NKX2.9, NKX6.1, DBX2, and PAX7 to pattern the developing neural tube in mammals (Muhr et al., 2001). The presence of an EH1 domain in the N-terminal of FEZF2 suggests that it may recruit TLE4 as a transcriptional co-repressor. Indeed, a previous study demonstrated that FEZF2 and TLE4 proteins in Xenopus physically interact with each other (Zhang et al., 2014).

Here, we investigate how FEZF2 regulates cell fate specification of cortical projection neurons. We demonstrate that, instead of being a terminal selector gene, Fezf2 functions as a selective repressor in multiple neuronal subtypes to repress the expression of genes associated with alternate subtypes. We show that, in corticothalamic neurons, FEZF2 and TLE4 co-regulate the molecular differentiation, dendritic morphology, and function of these neurons. Together with previous studies, our results suggest that distinct genetic programs act sequentially to regulate the differentiation of cortical projection neurons, with genes expressed in progenitor cells specifying the pan-cortical glutamatergic phenotype, and subtype-specifying transcription factors functioning in postmitotic cells to selectively repress the expression of genes associated with alternate subtype identities.

RESULTS

Fezf2 is required in postmitotic neurons to regulate the development of both subcerebral and corticothalamic identities

To determine whether Fezf2 acts in cortical RGCs or in postmitotic neurons to specify projection neuron subtype identities, we generated Fezf2 conditional knockout mice (Fezf2 cko) using a Fezf2Flox allele (Shim et al., 2012) and the NexCre allele (Goebbels et al., 2006) to delete Fezf2 in postmitotic neurons. Western blot analysis using a C-terminal FEZF2 antibody revealed that, although FEZF2 protein was absent in the Fezf2−/− null mutant cortices, a faint band of full-length FEZF2 was detected in the NexCre Fezf2Flox/− (Fezf2 cko) cortices, indicating that the recombination was incomplete (Figures 1A and 2B). In addition, a smaller 20-kDa band was detected in Fezf2 cko cortices, corresponding to the truncated C-terminal half and DNA-binding domain of FEZF2 (Figures 1A, S1A, and S1B).

Figure 1. Fezf2 functions in postmitotic neurons to specify cell identity.

(A) Western blot showing a reduction of full-length FEZF2 protein (arrow) in the Fezf2 cko cortices. The empty triangle points to residual FEZF2 protein in the Fezf2 cko cortices. The recombined Fezf2Flox allele produced a truncated FEZF2 (arrowhead) corresponding to the C-terminal half of the protein (see Figure S1A).

(B and C) Immunostaining for SOX5, BHLHB5, BCL11B, and TLE4 on sections from P0 Fezf2Flox/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf2 cko mice. The cortices were divided into 6 equal bins, and the numbers of cells in each bin were counted. Scale bars: 100 μm.

(D) Quantifications for marker+ neurons per 10,000 μm2 in each bin (width quantified: 250 μm). n = 3 brains per genotype, 3 sections per brain. In all graphs, error bars represent ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s t test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

(E) PLAP staining of brain sections of P7 Fezf2Flox/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf2 cko mice. The top row shows coronal cortical sections; the bottom row shows coronal sections at the level of pyramidal decussation. White arrows, dLGN; *pyramidal decussation. Scale bars: top row: 1 mm; bottom row: 500 μm.

See also Figure S1.

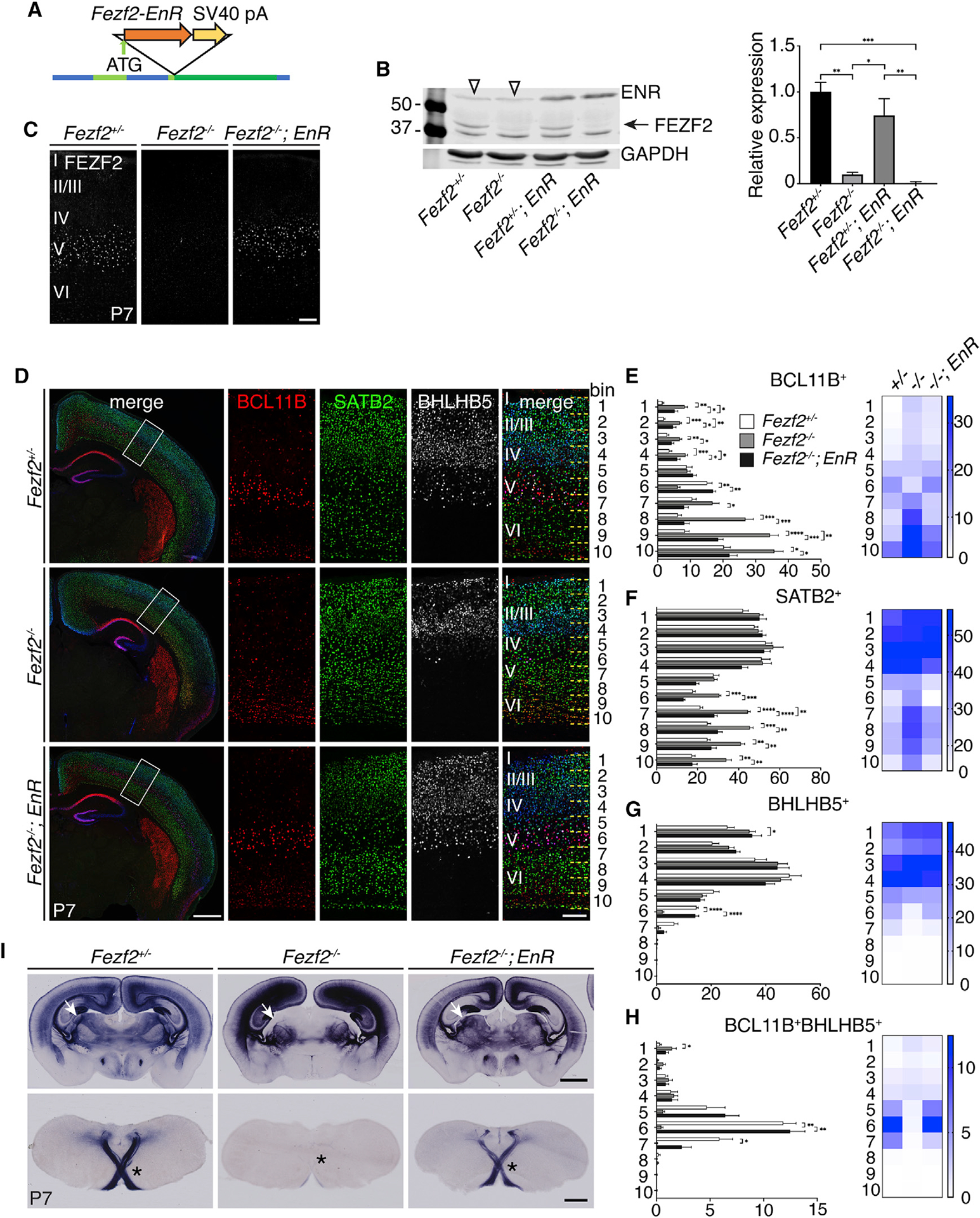

Figure 2. FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional repressor in cortical development.

(A) Strategy for generating the Fezf2-EnR BAC transgenic mouse line.

(B) Western blot analysis of dissected cortices at P7. FEZF2 signal was normalized to GAPDH signal in each lane. n = 3 brains per genotype. Arrow, FEZF2 protein; empty triangles, non-specific bands. Signal intensities were measured using ImageStudioLite and normalized to a Gapdh internal loading control. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s t test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001). Error bars represent SEM.

(C) Immunostaining for FEZF2 on brain sections from P7 Fezf2+/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR (EnR) mice. Scale bar: 100 μm.

(D) Immunostaining for BCL11B, SATB2, and BHLHB5 on P7 brain sections. Scale bar for low magnification: 500 μm. Scale bar for high magnification: 100 μm

(E–H) Quantifications of marker+ cells per 10,000 μm2 in each bin. Heatmaps show the mean numbers of cells per 10,000 μm2 for each bin. n = 3 mice per genotype, 3 sections per brain. In all graphs, error bars represent ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s t test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). Binning was shown in (D).

(I) PLAP staining of brain sections of P7 Fezf2+/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf2−/−; EnR mice. The top row shows coronal cortical sections; the bottom row shows coronal sections at the level of pyramidal decussation. Scale bars: 1 mm for top row; 500 μm for bottom row. White arrows, LGN; *pyramidal decussation.

See also Figure S2.

We compared cortices from Fezf2 cko mice to Fezf2+/− and Fezf2−/− cortices at postnatal day 0 (P0) and P7 (Figures 1B–1E and S1). The Fezf2− null mutant allele contained a PLAP (human placenta alkaline phosphatase) knockin gene under the control of the endogenous Fezf2 promoter and enabled us to directly observe the axons from Fezf2-expressing neurons (Chen et al., 2005a). The phenotypes of Fezf2 cko and Fezf2−/− cortices were similar: (1) the expression of subcerebral neuronal genes, including BCL11B and BHLHB5, was significantly reduced in layer 5 neurons (Figures 1B and 1D); (2) expression of corticothalamic neuron genes, such as TBR1, and genes expressed at high levels in the callosal neurons, such as SATB2, was increased in layer 5 (Figures S1C and S1D), suggesting that subcerebral neurons adopted corticothalamic and callosal identities; (3) expression of corticothalamic neuronal genes, such as TLE4, ZFPM2 (FOG2), and FOXP2 was decreased in layer 6 neurons (Figures 1C, S1E, and S1F); (4) expression of BCL11B was increased in layer 6, demonstrating that the molecular distinction between subcerebral and corticothalamic neurons failed to be refined in these cells (Figures 1B–1D, S1B, S1E, and S1F); (5) PLAP+ subcerebral axons were significantly reduced in the pyramidal decussation (Figure 1E); and (6) consistent with a previous report (Diao et al., 2018), PLAP+ corticothalamic axons to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) and other thalamic nuclei were severely reduced in both Fezf2 cko and Fezf2−/− mice (Figure 1E).

Despite these similarities, the phenotypes of Fezf2 cko and Fezf2−/− cortices were not identical, likely due to incomplete recombination in Fezf2 cko mice (Figure 1A). Specifically, Fezf2 cko cortices contained a few BCL11B+BHLHB5+ subcerebral neurons (Figures 1B–1D), and some PLAP+ corticospinal axons were able to project to the pyramidal decussation (Figure 1E). However, the similarity between the phenotypes of Fezf2 cko and Fezf2−/− mice indicates that Fezf2 is required in postmitotic neurons to regulate the molecular identities and axonal projections of both subcerebral and corticothalamic neurons.

FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional repressor to specify cortical projection neuron subtypes

FEZF2 consists of an N-terminal half containing an EH1 domain and other sequences and a C-terminal half consisting of six C2H2-type zinc-finger motifs (Hashimoto et al., 2000). Zinc-finger motifs are involved in DNA binding, and the EH1 domain recruits TLE family transcriptional co-repressors. To test whether FEFZ2 functions as a transcriptional repressor, an activator, or both, we generated expression plasmids encoding a full-length FEZF2 protein, a chimeric protein consisting of the transcriptional repressor domain of the engrailed protein (EnR) fused with the DNA-binding domain of FEZF2 (pCAG-Fezf2-EnR), or a chimeric protein consisting of the VP16 transcription activator domain (VP16) fused with the DNA-binding domain of FEZF2 (pCAG-Fezf2-VP16; Figure S2A). We co-electroporated each plasmid with a pCAG-EGFP plasmid into the cortical ventricular zone of embryonic day 15.5 (E15.5) wild-type embryos and examined the brains at P5 (Figure S2B). In all the electroporated brains, GFP+ neurons were located in layers 2 and 3 and GFP+ callosal axons were observed. GFP+ axons were not detectable in the thalamus or pons of brains electroporated with the pCAG-EGFP plasmid alone or in brains electroporated with pFezf2-VP16 plasmids. However, both full-length FEZF2 and FEZF2-EnR directed layer 2 and 3 neurons to project GFP+ axons into the thalamus and cerebral peduncle (Figure S2B).

To determine whether FEZF2 functions primarily as a transcriptional repressor during deep-layer neuronal differentiation, we generated a transgenic line expressing the FEZF2-EnR chimeric protein using a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) (Figure 2A). This BAC consisted of a 200-kb region flanking the Fezf2 gene. We inserted the FEZF2-EnR open reading frame at the endogenous Fezf2 translation start site, immediately followed by a transcription termination signal. Western blot analysis confirmed that endogenous FEZF2 protein was not expressed from the Fezf2-EnR transgenic allele (Figure 2B). Immunostaining showed that expression of the FEZF2-EnR protein recapitulates that of endogenous Fezf2 (Figure 2C).

We then determined whether FEZF2-EnR can rescue the defects resulting from a loss of Fezf2 by comparing the brains of Fezf2+/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice (Figures 2D–2I and S2C–S2E). The expression patterns of subcerebral neuronal markers, such as BCL11B and BHLHB5 (Figures 2D, 2E, and 2G), were restored in layer 5 neurons in Fezf2−/−;Fezf2-EnR mice. Similarly, the expression patterns of corticothalamic neuronal genes, such as TLE4, FOXP2, and ZFPM2 (Figures S2C–S2E) were restored. The ectopic expression of TBR1 (data not shown), FOSL2 (Figure S2C), and SATB2 (Figures 2D and 2F) in layer 5 was no longer detected. Furthermore, PLAP+ axons projected into the pyramidal decussation, the dLGN, and other thalamic nuclei in the Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice (Figure 2I). Thus, the Fezf2-EnR allele rescued the defects observed in layer 5 and layer 6 neurons in Fezf2−/−mice, indicating that FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional repressor.

Fezf2-EnR broadly rescues gene expression defects in the Fezf2−/− cortices

To further investigate how FEZF2 regulates projection subtype identities, we performed bulk RNA-seq analysis of cortices from P0 Fezf2−/−, Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR, and control Fezf2+/+ mice (Figures 3 and S3). Compared to the Fezf2+/+ mice, the expression levels of 408 genes were mis-regulated in the Fezf2−/− cortices (p < 0.05). 140 genes showed reduced expression, and 268 showed increased expression. DAVID analysis (https://david.ncifcrf.gov) revealed that the top Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with mis-regulated genes in Fezf2−/− cortices were extracellular region, multicellular organism development, collagen fibril organization, synapse, and cell junction. We examined the expression of these mis-regulated genes in specific subtypes of cortical neurons using the DeCoN dataset (Molyneaux et al., 2015) and found that 88 of the 140 genes showing reduced expression in Fezf2−/− cortices were subtype specific: 34 genes were enriched in subcerebral neurons; 43 in corticothalamic neurons; and 11 in corticocortical neurons. Among the 268 genes showing increased expression in Fezf2−/− cortices, 125 were subtype specific: 54 were enriched in corticocortical neurons; 43 in corticothalamic neurons; and 28 in subcerebral neurons (Figure 3A). Consistent with the immunohistochemistry results (Figures 2 and S2), RNA-seq analysis of the Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR cortices revealed that Fezf2-EnR broadly rescues these gene expression defects in the Fezf2−/− cortices (Figure 3A).

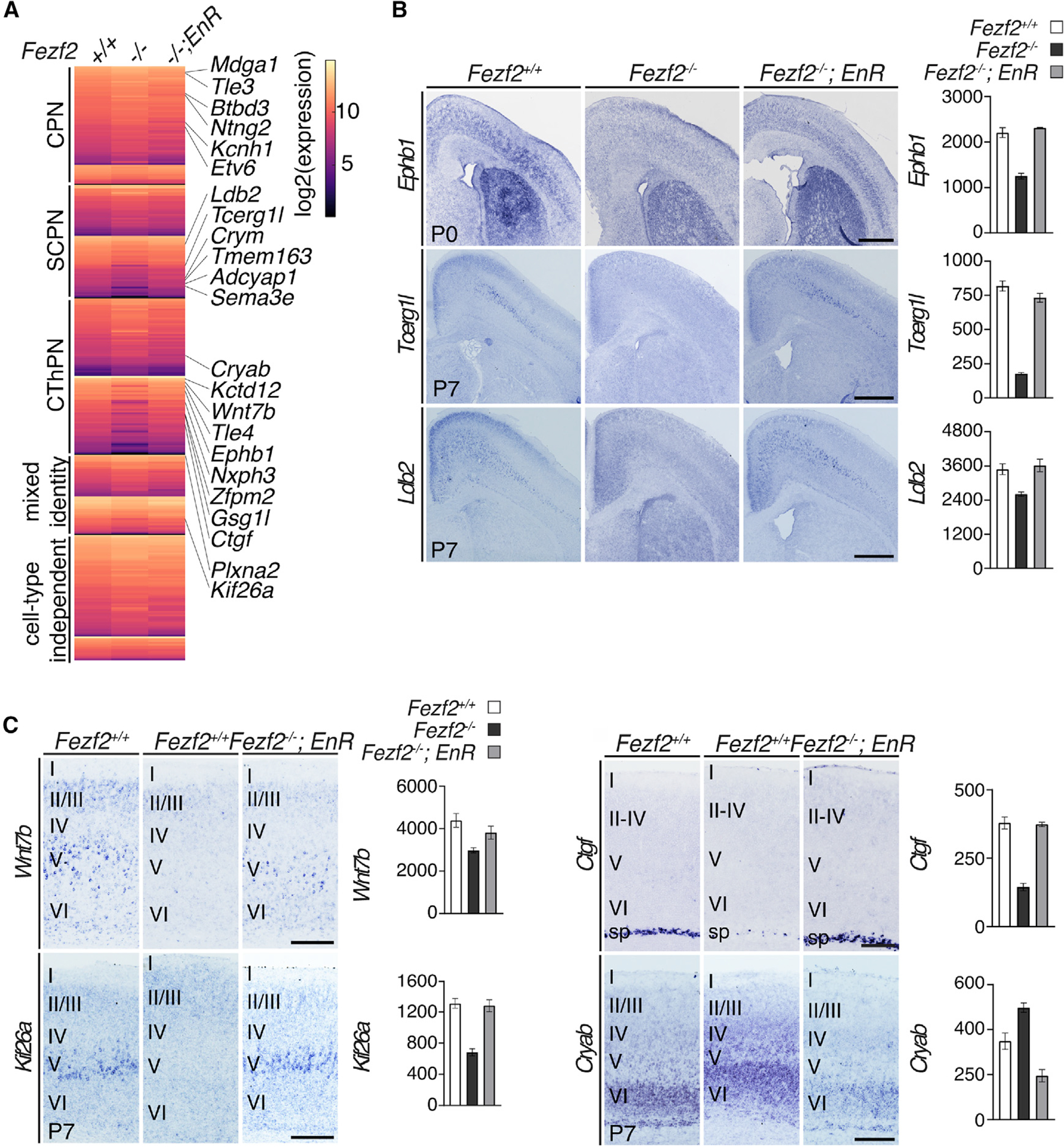

Figure 3. Genes mis-regulated in Fezf2−/− cortices were enriched in projection neuron subtype-specific genes.

(A) Left heatmap shows normalized gene expression levels in P0 Fezf2−/− (n = 4), Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR (n = 2), and control Fezf2+/+ (n = 3) cortices. The subtype specificities for the mis-regulated genes were determined based on the DeCoN dataset. CPN, callosal projection neuronal genes; CThPN, corticothalamic neuronal genes; SCPN, layer 5 subcerebral projection neuronal genes; mixed identity, genes expressed in more than one neuronal subtype; cell-type independent, genes expressed in all subtypes.

(B and C) In situ hybridization and RNA-seq analyses showed reduced expressions for Ephb1, Tcerg1l, Ldb2, Wnt7b, Kif26a, and Ctgf and increased expression of Cryab in Fezf2−/− cortices, which were restored in the Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice. Bar graphs showed normalized mRNA expression levels detected by RNA-seq in the cortices for the P0 Fezf2+/+ (n = 3 mice), Fezf2 −/− (n = 4 mice), and Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR (n = 2 mice) mice. Error bars represent SEM. Scale bars: 500 μm in (B) and 200 μm in (C).

We performed in situ hybridization to validate the RNA-seq analysis. Expressions of layer 5 subcerebral neuronal genes Ephb1, Tcerg1, and Ldb2 were reduced in the Fezf2−/− cortices, and their expressions were restored in layer 5 neurons in Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice (Figure 3B). Corticothalamic neuronal gene Wnt7b and the subplate neuronal gene Ctgf showed reduced expressions in the Fezf2−/− cortices; their expressions were rescued in the Fezf2-EnR mice (Figure 3C). Kif26a, a gene expressed in multiple neuronal subtypes, showed reduced expression in Fezf2−/− cortices; its expression was restored in Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice (Figure 3C). Expression of the corticothalamic neuronal gene, Cryab, was increased in the Fezf2−/− cortices; its expression was restored in Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice (Figure 3C). The broad rescue of gene expression defects in the Fezf2−/− cortices by the Fezf2-EnR allele demonstrates that FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional repressor in specifying cortical projection neuron identities.

TLE4 and FEZF2 are co-expressed in differentiating corticothalamic neurons and interact with each other

The N-terminal region of the FEZF2 protein contains an EH1 motif, which can recruit the TLE family co-repressors (Muhr et al., 2001). A previous study reported that Xenopus FEZF2 and TLE4 proteins directly interact with each other (Zhang et al., 2014). Indeed, co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that the mouse FEZF2 and TLE4 also can bind to each other (Figure 4A). To determine whether FEZF2 recruits TLE4 to regulate the development of deep-layer neurons, we performed immunostaining using antibodies against FEZF2 and TLE4, which showed that the two proteins were co-expressed in layer 6 neurons (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. TLE4 and FEZF2 can bind to each other and are co-expressed in the corticothalamic neurons.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation experiment showed that mouse FEZF2 and TLE4 proteins can bind each other. E, elution; FT, flow through; In, input. The bands around 50 KD are FEZF2-HIS-MYC; the bands around 75 KD are TLE4-FLAG-MYC.

(B) Immunostaining for TLE4 and FEZF2 on brain sections from E14.5, E16.5, and P0 in wild-type mice. Low-mag single z-plane image scale bar: 50 μm; high-mag maximum z-projection image scale bar: 10 μm.

(C) Combined retrograde tracing and immunostaining show that TLE4 is expressed in >99% of retrogradely labeled corticothalamic neurons in M1 (1,034 TLE4+CTB+ among 1,050 CTB+ cells), 0% of the traced subcerebral projection neurons (930 cells), and 0.1% of the callosal projection neurons (2 TLE4+CTB+ among 1,783 CTB+ cells). n = 3 mice for each injection location and 3 sections per brain were quantified. Low-mag scale bars: 1,000 μm. Scale bars in the second column from the right: 100 μm. Scale bars in the rightmost column: 20 μm.

To identify the neuronal subtype that expresses TLE4, we performed retrograde tracing by injecting fluorescence-conjugated cholera toxin beta subunit (CTB) into the thalamus, pyramidal decussation, or contralateral cortex (Figure 4C). More than 99% of retrogradely labeled corticothalamic neurons expressed TLE4, whereas labeled subcerebral neurons and callosal neurons did not (<1%). Thus, TLE4 is specifically expressed in corticothalamic neurons.

Corticothalamic axons developed normally in the Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice

To test the function of Tle4 in the specification and differentiation of corticothalamic neurons, we generated a Tle4 mutant allele (Tle4LacZ) by inserting a BGal-ires-Plap cassette into the 4th intron of the Tle4 gene (Figure S4A). The BGAL and PLAP reporters enabled us to label the cell bodies and axons of Tle4 heterozygous and mutant neurons (Figures S4B and S4D). In Tle4+/LacZ brains, BGAL expression recapitulated the endogenous pattern of TLE4 expression (Figure S4B). Immunostaining revealed that TLE4 protein was not present in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice (Figure S4C). In both Tle4+/LacZ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice, PLAP+ axons extended from cortex to the thalamus, with no obvious difference between control and mutant brains (Figure S4D). We performed anterograde tracing by injecting adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mcherry virus into the primary motor cortex (M1), primary somatosensory cortex (S1), and primary visual cortex (V1) cortical areas, which confirmed that corticothalamic axons developed normally in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice (Figure S4E; data not shown).

Molecular differentiation of corticothalamic neurons is defective in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice

We performed RNA-seq analysis of control and Tle4LacZ/LacZ P0 cortices (n = 3 mice for each genotype). 428 genes were mis-regulated in the Tle4LacZ/LacZ cortices (p < 0.05; Student’s t test). Using the DeCoN dataset (Molyneaux et al., 2015), we examined the neuronal subtype-specific expression of all mis-regulated genes. Among the 228 genes with reduced expression, 11 were associated with corticocortical neurons, 56 were specifically expressed in corticothalamic neurons, and 24 in subcerebral neurons. Among the 200 upregulated genes, 14 were associated with corticocortical neurons, 45 were enriched in subcerebral neurons, and 14 in corticothalamic neurons (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Molecular differentiation of corticothalamic neurons was defective in Tle4LacZ/LacZ brains.

(A) Heatmap showing normalized gene expression levels in the Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ cortices. The subtype specificities for the mis-regulated genes were determined based on the DeCoN dataset.

(B) Immunostaining of TLE4 or B-GAL and ZFPM2 in the P7 brains and quantifications of the numbers of TLE4+ or B-GAL+ and ZFPM2+ cells by bin and total cell counts.

(C) Immunostaining of TLE4 or B-GAL, BCL11B, and FEZF2 in the P7 brains and quantifications of the FEZF2+ and BCL11B+FEZF2+ cells by bin and total cell counts.

(D) Immunostaining of TLE4 or B-GAL, BCL11B, and BHLHB5 in the P7 brains and quantifications of the BCL11B+BHLHB5+ cells n = 3 brains per genotype, 3 sections per brain. Quantifications of marker+ cells per 10,000 μm2 in each bin are shown. In all graphs, error bars represent ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using the unpaired Student’s t test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Scale bars: low-mag, 500 μm; high-mag, 100 μm.

See also Figures S4–S6.

We performed immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization to validate the RNA-seq results. Consistent with the normal corticothalamic axons observed in Tle4LacZ/LacZ brains, the expression of TBR1 and SOX5, two genes essential for specifying a corticothalamic neuron identity, were not significantly affected (Figures S5A and S5B). However, the number of BGAL+ neurons was significantly reduced in layer 5 and layer 6a in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice (Figure 5B). Expression of other layer 6 neuron markers, such as ZFPM2 (Figure 5B) and FOXP2 (Figure S5C), was also significantly reduced. High expression levels of FEZF2, BCL11B, BHLHB5, Ldb2, and Tcerg1l are normally associated with layer 5 subcerebral neurons, but in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice, their expression was significantly increased in layer 6 (Figures 5C, 5D, S6A, and S6B).

The reduced numbers of BGAL+, ZFPM2+, and FOXP2+ cells in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice could be due to reduced neuronal production, increased cell death, or defective molecular differentiation, while the increased numbers of cells expressing BCL11B, FEZF2, and other subcerebral neuron markers in layer 6 could be due to a migration defect of layer 5 neurons or the mis-regulation of these genes in layer 6 neurons. To ascertain whether the production or migration of layer 5 and 6 neurons was affected in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice, we performed birthdating experiments by injecting EdU into pregnant mice on E12.5 or E13.5 and analyzing the brains of Tle4LacZ/LacZ and littermate control mice at P7. For both labeling dates, we saw no significant change in the number or distribution of EdU+ cells in the deep layers of Tle4LacZ/LacZ cortices (Figures S5A and S5B). We then stained sections from control and Tle4LacZ/LacZ cortices at E14, P0, and P7 with an antibody against activated caspase 3 (AC3) and observed no significant difference in the numbers of AC3+ cells between genotypes at any age (Figure S6C).

Together, these results indicate that, in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice, corticothalamic neurons were generated in appropriate numbers, migrated to their normal laminar destinations, and projected axons to the thalamus. However, the molecular differentiation of these neurons was impaired, resulting in the expression of genes normally associated with layer 5 subcerebral neurons.

Morphological and electrophysiological defects of corticothalamic neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice

We next investigated whether Tle4 is required for the morphological and functional differentiation of corticothalamic neurons. We injected retrobeads into the ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPM) of the thalamus (Landisman and Connors, 2007) of Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice (P27–P35) and performed whole-cell patch-clamp recordings and morphological analyses on labeled corticothalamic neurons in S1 (Figures 6A and 6B). Sholl analysis on reconstructed dendritic arbors revealed a significant reduction in the branching (F(2,286) = 3.4; p = 0.034) and length (F(2,253) = 7.3; p = 0.0009) of dendrites in mutant mice (Figure 6C). Mutant corticothalamic neurons also show significantly increased spine density, decreased spine head diameter, and increased spine length (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice show disrupted morphological and electrophysiological properties in corticothalamic neurons in S1, which were rescued by the Fezf2-EnR allele.

(A) Schematic illustration of retrobeads injection into VPM of thalamus and preparation of S1 slices for patch-clamp recording.

(B) A brightfield image overlaid with bead+ layer 6 corticothalamic neurons (arrowhead). Scale bars: 1 mm top image; 100 μm middle images. An enlarged view shows a beads+ corticothalamic neuron and its morphology (white arrow) revealed by biocytin-avidin-Alexa 488. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right: two examples of representative dendritic arbors reconstructed from the beads+ corticothalamic neurons in a Tle4+/+ and a Tle4LacZ/LacZ mouse.

(C) Sholl analysis on the dendritic intersection numbers and dendritic length. Left panel shows a significant difference among the genotypes (F(2,297) = 21.7; p < 0.0001. Tukey’s multiple comparison tests: between Tle4+/+ [n = 4 mice, 9 cells] and Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice [n = 5 mice, 11 cells], p < 0.0001; between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR [n = 4 mice, 10 cells] mice, p = 0.96. ***p < 0.001, between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice, Sidak’s multiple comparison test). Right panel shows dendritic length distribution. Genotype has a significant effect (F(2,253) = 7.54; p = 0.0007. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ, p = 0.0006; between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR, p = 0.42. ****p < 0.0001, between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ, Sidak’s multiple comparison test).

(D) Representative images of dendritic spines and their 3D projection images. Compared to the Tle4+/+ neurons (n = 4 mice, 12 cells, 20 spine lengths, 184 spine diameters), there was a significant increase in spine density (**p = 0.007; one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison) and spine length (****p < 0.0001; Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test) and a significant decrease in spine head diameter (**p < 0.0013) for the Tle4LacZ/LacZ corticothalamic neurons (n = 4 mice, 11 cells, 209 spine lengths, 194 spine diameters). No significant difference in spine density, spine length, or spine head diameter was detected between the corticothalamic neurons in Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice (n = 4 mice, 10 cells, 177 spine lengths, 192 spine diameters). Scale bars: 10 μm top image; 2 μm lower image.

(E) Representative action potential firing responses from a Tle4+/+, Tle4LacZ/LacZ, and a Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR corticothalamic neuron. Genotype has a significant effect on the current-AP responses (F(2, 165) = 24.1; p < 0.0001). Compared to Tle4+/+ neurons (n = 5 mice, 18 cells), Tle4LacZ/LacZ neurons (n = 6 mice, 12 cells) show increased firing in response to depolarizing current steps (p < 0.0001; Dunnett’s multiple comparison), which was reversed in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice (n = 5 mice, 13 cells; p = 0.14).

(F) AP threshold did not differ between Tle4+/+ (n = 5 mice, 18 cells), Tle4LacZ/LacZ (n = 6 mice, 12 cells), or Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR neurons (n = 5 mice, 13 cells; F(2,32) = 2.5; p = 0.09; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison).

(G) Genotype has a significant effect on membrane input resistance (F(2,30) = 10.8; p = 0.0003; one-way ANOVA). Tle4LacZ/LacZ neurons (n = 5 mice, 11 cells) show increased input resistance compared to Tle4+/+ neurons (n = 5 mice, 12 cells; p = 0.0003; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test), which was rescued in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR (n = 4 mice, 11 cells) mice (p = 0.87). Genotype has a significant effect on membrane capacitance (F(2,33) = 28.0; p < 0.0001). Compared to Tle4+/+ neurons (n = 5 mice, 12 cells), Tle4LacZ/LacZ neurons (n = 5 mice, 11 cells) show decreased membrane capacitance (p = 0.0003; Dunnett’s multiple comparison test), which was rescued in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice (n = 4 mice, 13 cells; between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR: p = 0.52).

(H) Left: representative mEPSC traces from Tle4+/+, Tle4LacZ/LacZ, and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR neurons. Right: cumulative plot on mEPSC amplitude is shown. Between Tle4+/+ (n = 5 mice, 8 cells, 1,135 measurements) and Tle4LacZ/LacZ (n = 5 mice, 6 cells, 1,069 measurements), *p < 0.02, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; between Tle4LacZ/LacZ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR (n = 4 mice, 9 cells, 1,158 measurements), p = 0.57. Inset: a significant decrease in mEPSC frequency in Tle4LacZ/LacZ neurons (n = 5 mice, 18 cells) between Tle4+/+ (n = 5 mice, 15 cells; *p = 0.015; Dunn’s multiple comparison following Kruskal-Wallis test) was restored by the Fezf2-EnR allele (n = 4 mice, 13 cells; between Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR: p = 0.99; Dunn’s multiple comparison test).

(I) No significant change in mIPSC amplitude and frequency was observed between Tle4+/+ (n = 5 mice, 14 cells) and Tle4LacZ/LacZ neurons (n = 5 mice, 13 cells; cumulative amplitude: p = 0.43; frequency: p = 0.17. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Note that the Tle4LacZ allele was labeled as Tle4− in the figure to prevent crowding.

All error bars represent ± SEM.

Patch-clamp recordings revealed that corticothalamic neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice exhibited increased excitability, as demonstrated by an increased number of action potentials (APs) firing in response to current steps (Figure 6E; F(1,110) = 38.9; p < 0.001); however, the AP threshold was unaffected (Figure 6F). Mutant corticothalamic neurons showed an increased membrane resistance and decreased membrane capacitance (Figure 6G; p < 0.05 for both). The amplitude (p = 0.02; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and frequency (t31 = 2.7; p = 0.011) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSC) were reduced in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice compared to wild-type mice (Figure 6H), but no significant change in the amplitude or frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSC) was observed (Figure 6I). These results collectively indicate that Tle4 is critical for the morphological development and function of corticothalamic neurons in somatosensory cortex.

Expression of FEZF2-EnR rescued the molecular, morphological, and functional defects of layer 6 neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ cortices

The co-expression of FEZF2 and TLE4 in corticothalamic neurons suggests that they function together in regulating the development of these neurons. To test this, we generated Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice and compared them to Tle4+/+ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice. The number of B-GAL+ cells in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice was restored to the number of TLE4+ cells seen in Tle4+/+ mice(Figures 7A and 7B). The expression of genes normally enriched in subcerebral neurons, such as BCL11B, BHLHB5, Tcerg1l, and Ldb2, was no longer increased in layer 6 neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice (Figures 7A, 7C–7F, S6A, and S6B). However, expression of corticothalamic neuron genes, including ZFPM2 and FOXP2, and the subplate gene Ctgf, was not restored (Figures S6C–S6F; data not shown). These results show that FEZF2 and TLE4 function together to prevent the high-level expression of subcerebral neuronal genes in corticothalamic neurons. They also suggest that, besides serving as a transcriptional co-repressor for FEZF2, TLE4 has additional functions in regulating the molecular differentiation of corticothalamic neurons.

Figure 7. FEZF2-EnR represses the increased expression of subcerebral neuronal genes in the corticothalamic neurons in the Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice.

(A) Immunostaining of TLE4 or B-GAL, BCL11B, and BHLHB5 in the cortices of P7 Tle4+/+, Tle4LacZ/LacZ, and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice. Scale bar: 100 μm.

(B) Quantifications of TLE4+ cells in the Tle4+/+ cortices and the B-GAL+ cells in Tle4LacZ/LacZ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR cortices.

(C) Quantifications of the numbers of BCL11B+BHLHB5+ cells.

(D) Immunostaining of TLE4, B-GAL, BCL11B, and FEZF2 in the cortices of P7 Tle4+/+, Tle4LacZ/LacZ, and Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice. Scale bar: 100 μm.

(E) Quantifications of the FEZF2+ cells by bin.

(F) Quantifications of the numbers of FEZF2+BCL11B+ cells. n = 3 brains per genotype, 3 sections per brain.

In all graphs, error bars represent ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s t test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). See also Figure S6.

We next compared the dendritic morphology and function of corticothalamic neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice to Tle4+/+ mice (Figure 6). Sholl analysis revealed that Fezf2-EnR rescued the decreased dendritic branching (p = 0.96) and length (p = 0.42) observed in Tle4LacZ/LacZ corticothalamic neurons (Figure 6C). The changes in spine density (p = 0.88), spine head diameter (p = 0.98), and spine length (p = 0.99) were also reversed (Figure 6D). Patch-clamp experiments showed that the Fezf2-EnR allele normalized the increased neuronal excitability associated with Tle4LacZ/LacZ neurons (Figure 6E). Corticothalamic neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR and wild-type mice showed similar membrane resistance (p = 0.53), capacitance (p = 0.87; Figure 6G), and mEPSC amplitude cumulative distribution and frequency (Figure 6H). These data suggest that FEZF2 and TLE4 together regulate the morphological and functional differentiation of corticothalamic projection neurons.

DISCUSSION

Deciphering the molecular logic for establishing neuronal subtype identities in the developing cerebral cortex is fundamental for understanding how neuronal diversity is established in the mammalian brain. In this study, we examined the molecular control of two broad classes of cortical projection neurons—the corticothalamic and the layer 5 subcerebral projection neurons—by focusing on the function of FEFZ2.

Prior studies demonstrated that FEFZ2 is a master regulator for CSMNs, a subpopulation of layer 5 subcerebral neurons. In Fezf2−/− mice, layer 5 subcerebral neurons were absent, and instead, the mutant layer 5b neurons demonstrated the molecular features and axonal projection patterns of corticothalamic or corticocortical neuron subtypes (Chen et al., 2005a, 2008; Molyneaux et al., 2005). Complementing these studies, ectopic expression of Fezf2 in late cortical progenitors or upper-layer neurons or in the progenitors of the lateral ganglionic eminence led to the differentiation of neurons with gene expression and axon projections associated with corticothalamic or subcerebral neurons (Chen et al., 2005b, 2008; De la Rossa et al., 2013; Lodato et al., 2014; Molyneaux et al., 2005; Rouaux and Arlotta, 2010, 2013), suggesting that FEZF2 functions as a selector gene for subcerebral neurons. To test this, Lodato et al. (2014) performed gene expression analyses of cortical progenitors and neurons that overexpressed FEZF2 and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis of neurospheres that overexpressed FEZF2-FLAG. Results from these experiments led the authors to conclude that FEZF2 functions as both a transcriptional activator and a repressor. They suggested that FEZF2 directly induces CSMN glutamatergic identity by activating expression of genes including Vglut1 (Slc17a7) and that it inhibits a GABAergic fate by repressing the transcription of genes such as Gad1 (Lodato et al., 2014). They further reported that FEZF2 directly activates CSMN-specific genes by binding to their proximal promoters and represses genes expressed in corticocortical projection neurons (Lodato et al., 2014).

Here, we directly tested whether FEZF2 functions as a transcriptional activator, a repressor, or both by comparing the activities of full-length FEZF2, FEZF2-EnR, and FEZF2-VP16 chimeric proteins using two different assays. Results from both overexpression and rescue experiments showed that FEZF2-EnR recapitulated the activity of full-length FEZF2 protein, while the FEZF2-VP16 was less relevant in our assays. Thus, in contrast to prior work, our studies demonstrate that FEZF2 functions primarily as a transcriptional repressor, in context of the formation of the corticospinal tract and neuronal identity. It is not clear why our results differ so markedly from those of Lodato et al. (2014), although it seems possible that ChIP-seq experiments may have overestimated the binding sites for FEZF2 in normal cortical neurons (Jain et al., 2015; Teytelman et al., 2013).

FEZF2 is required for establishing the molecular identity and axonal projections of both subcerebral and corticothalamic neurons. In the absence of Fezf2, subcerebral neurons exhibit molecular features and axonal projection patterns associated with corticothalamic or corticocortical neuron subtypes (Chen et al., 2005a, 2008; McKenna et al., 2011). Previous reports (Diao et al., 2018; Komuta et al., 2007) and our current study show that, in Fezf2−/− mice, corticothalamic neurons also exhibit defects in gene expression and axonal projections. We found that Fezf2 cko corticothalamic neurons showed increased expression of certain subcerebral neuronal genes, such as BCL11B and the truncated FEZF2, indicating that corticothalamic neurons partially assume the molecular identity of subcerebral neurons in the absence of Fezf2 function. Together, these results suggest that FEZF2 inhibits the expression of distinct and specific target genes in subcerebral neurons and in corticothalamic neurons, and by doing so, FEZF2 prevents each class of neurons from adopting an alternate neuronal subtype identity. Consistent with this, the Fezf2-EnR allele rescued the molecular identities and axonal projections of both the subcerebral and corticothalamic subtypes in Fezf2−/− mice.

How does FEZF2 function as a transcriptional repressor? One possibility is that FEZF2 binds to an enhancer or promoter sequence and physically prevents the binding of a transcriptional activator. Another possibility is that the binding of FEZF2 to an enhancer or promoter recruits additional transcriptional co-repressor(s), and together they actively repress gene expression. In Nex-Cre; Fezf2Flox/− mice, a truncated FEZF2 protein consisting of just the DNA binding domain was expressed, yet in these mice, subcerebral and corticothalamic neurons and their axons showed similar defects as in Fezf2−/− null mutant mice (Figures 1 and S1). This result indicates that the N-terminal half of the FEZF2 protein is essential for its transcriptional repressor function, likely by recruiting transcriptional co-repressors, and that FEZF2 is unlikely to repress gene expression simply by blocking the binding of a transcriptional activator.

Indeed, FEZF2 contains an EH1 motif, which can recruit TLE family transcription co-repressors (Hashimoto et al., 2000). The co-expression of FEZF2 and TLE4 in corticothalamic neurons suggests that TLE4 may be one of its co-repressors. Similar to Fezf2−/− mice, corticothalamic neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice showed increased expression of genes associated with subcerebral neurons, indicating that TLE4 is involved in refining the molecular identity of corticothalamic neurons by preventing high-level expression of some subcerebral neuronal genes. We found that the FEZF2-EnR allele, which does not depend on TLE family transcription co-repressors for its function, prevented the high expression levels of subcerebral neuronal genes and restored the functional properties of corticothalamic neurons in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice. These results support the conclusion that FEZF2 and TLE4 together repress the expression of FEZF2, BCL11B, and BHLHB5 in corticothalamic neurons. However, the reduced expression of corticothalamic neuronal genes, such as FOG2 and FOXP2 in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice, was not rescued by the Fezf2-EnR allele. Furthermore, although corticothalamic axons to the dLGN were missing in Fezf2−/− mice, they were present in Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice. Thus, although FEZF2 and TLE4 together refine the molecular differentiation and function of corticothalamic neurons, each plays additional independent roles. The identity of possible co-repressor(s) for FEZF2 in subcerebral neurons remains unknown.

Recent progress and our current study show that the subtype identity of a cortical projection neuron is specified in the postmitotic stage. Multiple transcription factors, including Tbr1 (Han et al., 2011; McKenna et al., 2011), Sox5 (Kwan et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2008), Fezf2 (Chen et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2008; Molyneaux et al., 2005), and the chromatin remodeling protein Satb2 (Alcamo et al., 2008; Britanova et al., 2008; Leone et al., 2015; McKenna et al., 2015), are essential for specifying cortical projection neuron subtype identities. A common phenotype of mice with mutations in these genes is that the affected neuronal subtypes exhibit gene expression profiles and axonal projection patterns associated with alternate neuronal subtypes. This suggests that TBR1, SOX5, and SATB2 likely also function as selective repressors in their respective neuronal subtypes to inhibit expression of genes associated with alternate identities. In the future, it will be important to test whether these proteins act as transcriptional repressors, activators, or both in the context of cortical projection neuron subtype specification. Another common feature shared by the Tbr1, Sox5, and Satb2 genes is that all are expressed in postmitotic neurons. Although Fezf2 is expressed by both cortical RGCs and deep-layer neurons, our results indicate that it is required in postmitotic neurons for specifying cortical neuron subtype identities. These results suggest that projection neuron subtype-specific features are established through repressing genes associated with alternate subtype identities during postmitotic neuronal differentiation.

Although different subtypes of cortical projection neurons have distinct morphologies, axonal projection patterns, and molecular profiles, they share a common cortical regional identity and use glutamate as an excitatory neurotransmitter. A fundamental question in brain development is whether a single genetic program specifies both the pan-cortical excitatory neuron identity and the subtype-specific identity of a cortical projection neuron or these features are specified by distinct genetic programs. Projection neuron subtype identities are mis-specified in Fezf2−/−, Tbr1−/−, Sox5−/−, and Satb2−/− mice, but mutant cortical neurons maintain their glutamatergic identity and fail to acquire molecular features associated with GABAergic neurons. Thus, these subtype identity genes are not required for the adoption of a pan-cortical glutamatergic identity.

A different set of transcription factors, expressed in the RGCs and/or intermediate progenitors, including Pax6, Tlx, Dmrt5, Dmrt3, Emx2, Ngn1, and Ngn2, are essential for establishing the regional and glutamatergic identities of cortical projection neurons (Desmaris et al., 2018; Konno et al., 2019; Kroll and O’Leary, 2005; Schuurmans et al., 2004). Based on our results and previous studies, we propose that the common versus unique characteristics of cortical projection neuron subtypes are specified sequentially during development. At early stages of corticogenesis, transcription factors expressed in cortical RGCs and/or intermediate progenitors (including Pax6, Tlx, Dmrt5, Dmrt3, Emx2, Ngn1, and Ngn2) act in parallel pathways to ensure the generation of cortical glutamatergic projection neurons and prevent the production of ventral GABAergic neurons (Desmaris et al., 2018; Konno et al., 2019; Kroll and O’Leary, 2005; Schuurmans et al., 2004). As postmitotic cortical neurons begin to migrate and differentiate, genes such as Fezf2, Tbr1, Sox5, and Satb2 repress the expression of genes associated with alternate neuronal subtype identities to establish specific subtype-specific identities. In the future, it will be necessary to rigorously test whether the proteins encoded by these genes function as transcriptional repressors or activators during development and to determine how the expression of neuronal subtype identity genes is initially activated. Answers to these questions will be invaluable for designing novel and efficient strategies for using directed differentiation or trans-differentiation methods to repair damaged brain circuits in disease and injury.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Bin Chen (bchen@ucsc.edu).

Materials availability

The Tle4LacZ and Fezf2-EnR mouse lines will be deposited to the Jackson Laboratory. All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact, but we may require a payment and/or a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application.

Data and code availability

The RNA-seq data for the Fezf2−/−, Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR, and littermate control Fezf2+/+ cortices, and for the Tle4LacZ/LacZ and littermate control Tle4+/+ cortices can be accessed using GEO: GSE160202 and GEO: GSE142269, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice used in this study

Experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of California at Santa Cruz and at University of Arizona College of Medicine Phoenix, and were performed in accordance with institutional and federal guidelines. Experiments performed at Fudan University were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

We generated the Tle4LacZ allele by inserting a LacZ-ires-Plap cassette in the intron after the exon 4 of the Tle4 gene, using the targeted gene trap strategy (Friedel et al., 2005). Southern hybridization was performed to screen the E14a ES cell clones and identify the correct targeting.

The bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone RP23-141E17 was modified by inserting the cDNA encoding the ENGRAILED transcriptional repressor domain (EnR) fused with the DNA binding domain of FEZF2, followed by the SV40 polyadenylate site (Fezf2-EnR), at the start codon of the mouse Fezf2 gene. The BAC DNA was purified and sequenced and used for injection to generate the Fezf2-EnR transgenic mouse line.

The day of the vaginal plug detection was designated as E0.5. The day of birth was designated as P0. The genders of the embryonic and early postnatal mice were not determined.

The following mice were used in this study:

Fezf2+/+, Fezf2+/− and Fezf2−/− mice: P0, P7, and adult, both male and female mice were used.

Fezf2flox/+ and Fezf2Flox/Flox mice: adult, both male and female mice were used.

Nex-Cre mice: adult, both male and female mice were used.

Nex-Cre; Fezf2+/− and Nex-Cre; Fezf2−/Flox mice: P0 and P7, both male and female mice were used.

Fezf2-EnR mice: adult, both male and female mice were used.

Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR mice: P0, P7, and adult, both male and female mice were used.

Tle4+/+, Tle4+/LacZ and Tle4LacZ/LacZ mice: P0, P7, adult, both male and female mice were used.

Tle4LacZ/LacZ; Fezf2-EnR mice: P0, P7, adult, both male and female mice were used.

Cell lines used in this study

Neuro-2a (ATCC CCL-131) cells were used in this study for protein co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in 145 mm culture dishes (Greiner, #639960).

METHOD DETAILS

PLAP staining

Human placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) staining was performed as described previously (Chen et al., 2005a). P7 mice were anesthetized and 4% paraformaldehyde was delivered via trans-cardiac perfusion. Brains were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours at 4°C and then immersed in 30% sucrose in PBS for 24 hours. Brains were then frozen and sectioned into 50 μm sections using a sliding microtome (Thermo Scientific, Microm HM 430). Sections were washed 3 times in PBS, immersed in a 1:50 solution of NBT/BCIP (Roche, 11681451001) in 0.1M Tris-HCl pH 9.5, 0.1M NaCl, and then incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. Sections were then washed in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 5 times over the course of 2 hours at 37°C to remove background. Sections were then mounted in Fluoromount-G.

Immunohistochemistry

4% paraformaldehyde was delivered to mice via trans-cardiac perfusion. Brains were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% saponin, and PBS for 24 hours at 4°C, followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in PBS. Immunohistochemistry was performed using standard protocols. Briefly, twenty-five-μm-thick brain sections were permeabilized with 0.03% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Slides were then immersed in citrate buffer (10mM citric acid monohydrate, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 6.0), brought to a boil in a microwave and rested for 1 hour at RT. Slides were then incubated in a blocking buffer (5% donkey serum, 0.03% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 minutes. Blocking buffer was removed, and the sections were incubated with primary antibodies (diluted in the blocking buffer) for 24 hours at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: GFP (Chicken, Aves Labs GFP-1020), BCL11B (Rat, Abcam ab18465), TBR1 (Rabbit, Abcam ab31940), SOX5 (Rabbit, Abcam ab94396), FEZF2 (Rabbit, IBL F441), TLE4 (Mouse, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-365406), FOXP2 (Rabbit, Abcam ab16046), ZFPM2 (Rabbit, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), B-GAL (Chicken, Abcam ab9361), activated caspase 3 (Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology #9661), BHLHB5 (Goat, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-6045), SATB2 (Rabbit, Abcam ab34735), FOSL2 (Rabbit, Sigma HPA004817), and GAPDH (Covance, MMS-580S), The sections were washed in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488, Alexa 546, or Alexa 647 for 2 hours at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch and Invitrogen. Finally, the sections were counterstained with DAPI for 5min before being mounted in Fluoromount-G.

Protein co-immunoprecipitation

Neuro-2a (ATCC CCL-131) cells were cultured in 145 mm tissue culture treated dishes (Greiner, #639960) at 37°C with 5% CO2 and transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo, #L3000001) with the following plasmid combinations: Fezf2-his-myc + Tle4-flag-myc + GFP-his-myc, Fezf2-his-myc + GFP-his-myc, Tle4-flag-myc + GFP-his-myc, or GFP-his-myc alone. 24 hours later, cells were harvested, and nuclear extract was isolated using the Active Motif Nuclear Complex Co-IP kit (cat. #54001). The extracts were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with either Flag-tagged beads (Sigma, #M8823) or GFP antibody (Rabbit, Invitrogen A11122) and eluted with 0.1M glycine, pH 2.5 at RT for 30 minutes with occasional agitation. The samples were denatured at 100°C for 5 minutes in 5x sample buffer, run on an 8% SDS-PAGE at 70V for 2 hours, transferred to PVDF (Sigma, IPVH85R) at 150mA for 90 minutes, and blocked for one hour in 1% non-fat dry milk-TBST. 2ug of Fezf2 (Rabbit, IBL F441), Tle4 (Mouse, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-365406), GFP (Chicken, Aves Labs GFP-1020), or Myc (Goat, Abcam ab9132) primary antibodies were added and incubated overnight at 4°C on an orbital shaker. The blot was developed with Li-Cor secondary antibodies (#926-32212, 926-32214, 926-68073, 926-68072) or Alexa 488 for one hour and images were processed using ImageStudioLite.

Western blotting

P7 cortices were dissected in ice cold 1X PBS supplemented with cOmplete Mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets (Roche, 04 693 159 001) and transferred to RIPA buffer for 20 minutes on ice. The tissue was homogenized by pushing through 25G and 27G needles sequentially, 3 times each. Cell homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, denatured at 100°C for 5 minutes in 5x sample buffer, run on an 8% SDS-PAGE at 70V for 2 hours, transferred to PVDF (Sigma, IPVH85R) at 150mA for 90 minutes, blocked for one hour in 1% non-fat dry milk-TBST, and immunoblotted overnight with 2ug of FEZF2 (Rabbit, IBL F441) primary antibody. The blot was developed with Li-Cor Donkey anti Rabbit secondary antibody (#926-68073) for one hour and images were processed using ImageStudioLite.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed using a previously published protocol (Guo et al., 2013). In brief, digoxigenin-labeled probes used in this study were made from cDNAs amplified by PCR using the following primers:

| Gene | Forward Primer 5′ → 3′ | Reverse Primer 5′ → 3′ | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tcerg1l | CTCTCCCCACTGTGGTATTAGC | CAGAACTATTTCCCCTCGTGAC | This paper |

| Ldb2 | CACCTGATTACGCTGTCCATAG | AAGTTCAACACACGAGGGAGAT | This paper |

| Ctgf | AAATCGCCAAGCCTGTCAAG | GGCACTGTGCGCTAATGAAC | This paper |

| Cryab | CTCAGCCCTGCCTGTGTT | ATCTGGGCCAGCCCTTAG | This paper |

| Ephb1 | CACATCCATCTCCCTTTGCT | TCCAGAAACCCTTTCCCTCT | (Lodato et al., 2014) |

| Kif26a | TCCTCAGCTCCAGACTCCAT | GCGACAGTCTTTCCATCTCC | (Lodato et al., 2014) |

| Wnt7b | ACGCAATGGTGGTCTGGT | AAGGGCCTGAGGAAATGG | Allen Brain Atlas |

Amplified DNA fragments were ligated into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) plasmids, transformed into competent E. coli cells, and plated overnight on LB+Agar+Ampicillin plates. Colonies were picked, grown overnight in 3 mL LB+Ampicillin, and purified via miniprep kits (Sigma-Aldrich). Purified plasmids were sequenced to ensure sequence fidelity, and to determine insert orientation. Plasmids were then linearized with restriction enzymes from New England Biotech, and in vitro transcription reactions were performed with either T7 (NEB) or Sp6 (Promega) RNA polymerases, depending on insert orientation, in the presence of DIG-labeled nucleotides (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissue was prepared as previously described (Guo et al., 2013), and treated with DIG-labeled probes overnight at 65°C. Slides were developed with NBT/BCIP stock solution (Sigma-Aldrich).

EdU labeling

Timed pregnant Tle4+/LacZ mice were injected with a single dose of EdU (50mg/kg body weight; Thermo Fisher Scientific, E10187) at E12.5 or E13.5. Brains were collected at P7. EdU was detected via a click-chemistry reaction containing the following reagents per 1 mL of reaction: 950ul 100mM Tris PH 7.4, 40ul 100 mM CuSO4, 10ul 200 mg/mL sodium ascorbate, and 1ul azide 488 or 555. Tle4LacZ/LacZ and littermate Tle4+/+ control mice were analyzed.

Anterograde tracing using AAV

0.25 μl AAV2-CMV-mCherry virus (Vector Biosystems Inc.) were injected into the M1, S1 or V1 of Tle4LacZ/LacZ and littermate control Tle4+/LacZ or Tle4+/+ mice at P21. The brains were collected at P35 and sectioned at 50-μm thickness.

Retrograde tracing

Retrograde tracing was performed using Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated cholera toxin subunit β (CTB) injections. 8 mg/ml CTB in PBS was used for all injections, and CTB solution was injected through a pulled glass pipet attached to a Picospritzer III (Parker). P4 mice were anesthetized, the pyramidal decussation was identified visually, and 1 μl CTB was injected. 0.2 to 0.5 μl CTB was injected into S1 in anesthetized P4 mice and injection sites were confirmed after brain collection at P7. Corticothalamic neurons were labeled by CTB injection (0.2 μl) into the thalamus at P21 (coordinates: A/P −1.3 mm, M/L 3 mm, Z 3.15 mm) and injection sites were confirmed after brain collection at P28.

Cloning of the pCAG-Fezf2, pCAG-Fezf2-EnR, and the pCAG-Fezf2-VP16 expression plasmids

The cloning of pCAG-Fezf2 plasmid was reported previously (Chen et al., 2005a). The EnR and VP16 plasmids were obtained from Dr. Thomas Jessell (Columbia University). The cDNA for DNA binding domains of FEZF2 was amplified using primers 5′-GATCGAATTCTCAGCTCTGAACTGTCCTGGCTAGGTC-3′ and 5′-GATCGGATCCGCCGCCGCCATGGAGCCCCGGCCTGCTGCGTTAG AGGC-3′. The cDNA for the EnR domain was amplified using primers 5′-GATCGATATCAAGCTTGGGCTGCATAGATCCCAG-3′ and 5′-GATCGGATCCGCCGCCACCATGGAGTTCCGCGATGCCCTGGAGGATCGC-3′. The cDNA for VP16 domain was amplified using primers 5′-GATCGGATCCGCCGCCACCATGGCCCCCCCGACCGATGTCAGCCT-3′ and 5′-GATCGATATCCCCACCGTACTCGTCAATTCCAA-3′. The amplified DNA fragments were ligated into pCAG vector, using NotI and XhoI restriction sites. Sanger DNA sequencing was performed to ensure no mutation was generated during the cloning.

In utero electroporation

In utero electroporation experiment was performed according to a published protocol (Chen et al., 2005a). In utero electroporation (IUE) of wild-type CD-1 embryos was performed at E15.5. Plasmids pCAG-Fezf2, pCAG-Fezf2-EnR, or pCAG-Fezf2-VP16 were mixed with pCAG-EGFP (Addgene #11150) (final concentration of 1–2 μg/μl at a molecular ratio of 3:1, 0.5 μL each embryo) and 0.05% Fast Green (Sigma), and injected into the lateral ventricle of embryos using a beveled pulled glass micropipette. The control brains were electroporated with pCAG-EGFP plasmids alone. Five electrical pulses (duration: 50 ms) were applied at 35V across the uterine wall with a 950 ms interval between pulses. Electroporation was performed using a pair of 7-mm platinum electrodes (BTX, Tweezertrode 45-0488, Harvard Apparatus) connected to an electroporator (BTX, ECM830). The electroporated brains were collected at P5.

Image acquisition and analysis

Images for quantitative analyses were acquired with a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope. Laser power and gain were adjusted until < 1% of pixels were saturated. Cell counting was performed on single z-slices with FIJI. Z-slices were divided into 500 μm or 250 um wide regions and split into equally sized bins. Individual channels were adjusted with auto threshold “Moments,” or a manual threshold was applied to discern BCL11B high versus low expressing cells. The dilate, erode, and watershed functions were sequentially used before particles were analyzed with a circularity of 0.3–1.0 and size exclusion of > 1 μm. Brightfield images were acquired with a Zeiss AxioImager Z2 widefield microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam 506 (color) camera.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0, or R. Only single Z-slice confocal images were used in cell quantifications. For each brain, the number of marker+ cells in the cortex were quantified in a 500- or 250-mm-wide region from 3 sections each for S1, M1 and V1 areas. Care was taken to match the anterior-posterior, medial-lateral positions for the chosen areas between the mutant and control genotypes. For each genotype and each age, 3 different brains were analyzed. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and statistical significance for multiple comparisons was determined using the ordinary one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance for single comparisons was determined using the unpaired t test. Significance was set as * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 for and ****p < 0.0001 all significance tests.

RNA-seq analysis of Tle4LacZ/LacZ, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR cortices at P0

Cortices were dissected from P0 Tle4LacZ/LacZ (n = 3 mice) and littermate control Tle4+/+ (n = 3) mice, P0 Fezf2−/− (n = 4), Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR (n = 2), and littermate Fezf2+/+ mice (n = 4). Total RNA from each pair of cortical hemispheres was isolated using the RNAe-say kit (QIAGEN) and used to prepare RNA-seq libraries (Illumina RNA Truseq Library Prep protocol). Libraries were paired-end (50 nucleotides per end) sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq2000 platform. The sequences were processed and analyzed for differential expression as previously described (Betancourt et al., 2014). The RNA-seq data for the Fezf2−/−, Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR, and control Fezf2+/+ cortices, and for the Tle4LacZ/LacZ and control Tle4+/+ cortices can be accessed using GSE160202 and GSE142269, respectively.

Electrophysiology and neuronal morphology

Whole cell recording was conducted in the primary somatosensory cortex (V1). To label layer 6 corticothalamic neurons, 50nl of retrobeads (Lumafluor) were injected into the POM nucleus unilaterally at least 24h prior to recording. 350-μm slices were made after a block cut of the posterior brain with a 45° angle to the mid-sagittal plane. Slices were cut in ice-cold ACSF (containing 126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, and 10 mM glucose saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2). Slices were incubated at 32°C for 30 min before being transferred to the recording chamber. Beads+ neurons with soma in layer 6 were identified under a 60X objective (NA = 0.9). Only neurons with their soma at least 50 μm below the slice surface were targeted for whole cell recordings. The internal electrode solution contains: 130 mM K-gluconate, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM KCl, 0.3 mM GTP-Na, 4 mM ATP-Mg, 2 mM NaCl,1 mM EGTA and 14 mM phosphocreatine (pH 7.2, 295–300 mOsm). 0.15% (W/V) biocytin was added when neuron morphology data were desired.

Neuronal signals were amplified using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Forster City, CA), low-pass filtered at 1 kHz (current) or 10 kHz (voltage signals), and digitized at 20 kHz using a Digidata 1440A interface and pClamp 10.6 (Molecular Devices). mEPSCs were measured with D-AP5 (50 μM, Tocris) and tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM, Tocris) included in the ACSF. To measure mIPSCs, TTX (1 μM) and CNQX (10 μM) were included and a symmetrical [Cl−] electrode internal solution (containing: 125 mM KCl, 2.8 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM Mg2+-ATP, 0.3 mM Na3GTP, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA and 10 mM phosphocreatine, pH 7.25, ~300 mOsm) was used. In experiments where neuronal excitability was measured, a series of current steps (−100 to 500pA in 50 pA increment) were injected, and numbers of AP firing were manually quantified.

To reconstruct neuronal morphologies, slices were fixed in 4% PFA overnight, followed by incubation with avidin-Alexa 488 (Invitrogen) for 24 h in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100. Slices were washed and mounted on slides with a 350-μm spacer to prevent crushing the tissue. Neuronal dendritic arbors were acquired by collecting Z stack images on a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710). Maximal projection images were imported into FIJI/ImageJ, and neurite arborization and Sholl analysis (Sholl, 1953) were done using the Simple Neurite Tracer plugin. Due to the length of apical dendrites, dendrites were frequently cut off. Therefore, only basal dendrites were used for Sholl analysis. Morphometric features extracted included dendritic arbor, length, and number of intersections at various distances from soma. For dendritic spine analyses, Z stacks of spines from the basal dendrites (100–450 μm away from soma) were collected with a 63x objectives (Plan-Apochromat, NA 1.4). 512 × 3 512 pixels with 4 × digital zoom and 0.2 μm Z step size were used for Z stack acquisition. Imaris software (V8.02, Bitplane, South Windsor, CT) was used to measure spine head diameter, length, and density (Peng et al., 2016).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The statistical details of the experiments can be found in the figure legends and Method details section under the experiments. All n values and what n represents are listed in the figure legends, and all p values obtained are listed in the figure legends. GraphPad Prism version 8 was used to perform statistical tests in this study. The statistical tests used for each experiment are indicated in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Chicken anti-GFP polyclonal | Aves Labs | GFP-1020; RRID:AB_2307313 |

| Rat anti-BCL11B monoclonal | Abcam | ab18465; RRID:AB_2064130 |

| Rabbit anti-TBR1 polyclonal | Abcam | ab31940; RRID:AB_2200219 |

| Rabbit anti-SOX5 polyclonal | Abcam | ab94396; RRID:AB_10859923 |

| Rabbit anti-FEZF2 polyclonal | IBL | F441; RRID:AB_529237 |

| Mouse anti-TLE4 monoclonal | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-365406; RRID:AB_10841582 |

| Rabbit anti-FOXP2 polyclonal | Abcam | ab16046; RRID:AB_2107107 |

| Rabbit anti-ZFPM2 polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-10755; RRID:AB_2218978 |

| Chicken anti-B-GAL polyclonal | Abcam | ab9361; RRID:AB_307210 |

| Rabbit anti-Activated Caspase 3 polyclonal | Cell Signaling Technology | 9661; RRID:AB_2341188 |

| Goat anti-BHLHB5 polyclonal | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-6045; RRID:AB_2065343 |

| Rabbit anti-SATB2 polyclonal | Abcam | ab34735; RRID:AB_2301417 |

| Rabbit anti-Fosl2 polyclonal | Sigma | HPA004817; RRID:AB_1849014 |

| Mouse anti-GAPDH monoclonal | Biolegend | 919501; RRID:AB_2565211 |

| Donkey anti-Chicken Alexa Fluor 488 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | 703-545-155; RRID:AB_2340375 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | R37114; RRID:AB_2556542 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A-21206; RRID:AB_2535792 |

| Donkey anti-Goat Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A-11055; RRID:AB_2534102 |

| Donkey anti-Rat Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A-21208; RRID:AB_141709 |

| Goat anti-Chicken Alexa Fluor 546 | Invitrogen | A-11040 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 594 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | 715-585-150; RRID:AB_2340854 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 | Invitrogen | A-10040; RRID:AB_2534016 |

| Donkey anti-Goat Alexa Fluor 546 | Invitrogen | A-11056 |

| Donkey anti-Rat Alexa Fluor 555 | Abcam | Ab150154; RRID:AB_2813834 |

| Donkey anti-Chicken Alexa Fluor 647 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | 703-606-155; RRID:AB_2340380 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 647 | Invitrogen | A-31571; RRID:AB_162542 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 | Invitrogen | A-31573; RRID:AB_2536183 |

| Donkey anti-Goat Alexa Fluor 647 | Invitrogen | A-21447; RRID:AB_141844 |

| Donkey anti-Rat Alexa Fluor 647 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | 712-605-153; RRID:AB_2340694 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse HRP | Invitrogen | A16011; RRID:AB_2534685 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit HRP | Invitrogen | A16035; RRID:AB_2534709 |

| Rabbit anti GFP | Invitrogen | A1122; RRID:AB_221569 |

| Goat anti MYC | Abcam | Ab9132; RRID:AB_307033 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG IRDye 800 | Li-Cor | 926-32212; RRID:AB_621847 |

| Donkey anti-Goat IgG IRDye 800 | Li-Cor | 926-32214; RRID:AB_621846 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG IRDye 680 | Li-Cor | 926-68073; RRID:AB_10954442 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG IRDye 680 | Li-Cor | 926-68072; RRID:AB_10953628 |

| Anti FLAG-M2 Magnetic Beads | Sigma | M8823; RRID:AB_2637089 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAV2-CMV-mCherry virus | Vector Biosystems Inc. | #7104 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Mouse cortex | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| EdU | Thermo Fisher | E10187 |

| (+)-Sodium L-ascorbate | Sigma-Aldrich | A7631 |

| Copper (II) Sulfate (CuSO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | 451657 |

| Rhodamine Azide | Invitrogen | A20012 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Azide | Invitrogen | A10266 |

| Cholera Toxin Subunit B, Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate | Invitrogen | C22843 |

| Saponin | Sigma-Aldrich | 470366 |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | MP Biomedicals | 150146 |

| Citric Acid Monohydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | C0706 |

| Horse Serum | GIBCO | 16050-114 |

| T7 Polymerase | New England Biotechnology | M0251 |

| SP6 Polymerase | Promega | P1085 |

| DIG-Labeled Nucleotides | Sigma-Aldrich | 11277073910 |

| NBT/BCIP stock solution | Sigma-Aldrich | 11681451001 |

| SpeI Restriction Enzyme | New England Biotechnology | R3133 |

| SalI Restriction Enzyme | New England Biotechnology | R0138 |

| NcoI Restriction Enzyme | New England Biotechnology | R0193 |

| NotI Restriction Enzyme | New England Biotechnology | R0189 |

| XhoI Restriction Enzyme | New England Biotechnology | R0146 |

| Trypan Blue Stain (0.4%) | GIBCO | 15250-061 |

| Red Retrobeads | Lumafluor | R170 |

| Avidin Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A21370 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| GenElute HP Plasmid Miniprep Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | NA0160 |

| Qiaquick PCR Purification Kit | QIAGEN | 28106 |

| RNeasy Plus Mini Kit | QIAGEN | 74134 |

| TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit | Illumina | RS-122-2001 |

| Nuclear Complex Co-IP kit | Active Motif | 54001 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Fezf2−/−, Fezf2−/−; Fezf2-EnR and control RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE160202 |

| Tle4LacZ/LacZ and control RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE142269 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Neuro-2a | ATCC | CCL-131 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Fezf2− | Chen et al., 2005a | University of California, Santa Cruz |

| Mouse: Fezf2Flox | Han et al., 2011 | Yale University |

| Mouse: Fezf2-EnR | This Paper | N/A |

| Mouse: Tle4LacZ | This Paper | N/A |

| Mouse: Nex-Cre | Goebbels et al., 2006 | Max-Planck-Institute of Experimental Medicine |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Forward primers for genotyping Tle4 wildtype allele: GAGATGTGGCTAC AGAAGAGGTTCAGAGAC | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for genotyping Tle4 wildtype allele: ATCTGCCCC TTGCTATTCCTGCTTGCTCTC | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for genotyping Tle4LacZ allele: TGCTCTCCCACAAGCTCGCTTGTCGTTCAG |

This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for genotyping Tle4LacZ allele: AAGAGGGCTCTGTCCTCCAGTCTCCTCCAC | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for genotyping Fezf2 wildtype allele: TTGAATGCAAATGGGTGACCGGGCCG | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for genotyping Fezf2 wildtype allele: GTTTTAGAAGTGGCCGGTGACGCTCC | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for genotyping Fezf2− allele: CACCCCGGTGAACAGCTCC TCGCCCTTGCTCACCAT | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for genotyping Fezf2− allele: CTGCATGGCTCGGAACG CATCTCCTTGGCGGTGGGGGAAAGAG | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for genotyping Fezf2-EnR allele: CAAAATCGGTTACGGTTGAGTAATA | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for genotyping Fezf2-EnR allele: ACCATGCCACTTCCCTTCTCAG | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for genotyping Fezf2Flox allele: TGCCTTGTACACCTTTCTCT | Han et al., 2011 | Yale University |

| Reverse primers for genotyping Fezf2Flox allele: GAGACCTAGGCAAGGGACAGT | Han et al., 2011 | Yale University |

| Forward primer for genotyping Nex-Cre allele: GAGTCCTGGAATCAGTCTTTTTC | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primer for genotyping Nex-Cre allele: CCGCATAACCAGTGAAACAG | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for Tcerg1l in situ hybridization probe template: CTCTCCCCACTGTGGTATTAGC | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for Tcerg1l in situ hybridization probe template: CAGAACTATTTCCCCTCGTGAC | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for Ldb2 in situ hybridization probe template: CACCTGATTACGCTGTCCATAG | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for Ldb2 in situ hybridization probe template: AAGTTCAACACACGAGGGAGAT | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for Ctgf in situ hybridization probe template: AAATCGCCAAGCCTGTCAAG | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for Ctgf in situ hybridization probe template: GGCACTGTGCGCTAATGAAC | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for Cryab in situ hybridization probe template: CTCAGCCCTGCCTGTGTT | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for Cryab in situ hybridization probe template: ATCTGGGCCAGCCCTTAG | This Paper | N/A |

| Forward primers for Ephb1 in situ hybridization probe template: CACATCCATCTCCCTTTGCT | Lodato et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Reverse primers for Ephb1 in situ hybridization probe template: TCCAGAAACCCTTTCCCTCT | Lodato et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Forward primers for Kif26a in situ hybridization probe template: TCCTCAGCTCCAGACT CCAT | Lodato et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Reverse primers for Kif26a in situ hybridization probe template: GCGACAGTCTTTCCATCTCC | Lodato et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Forward primers for Wnt7b in situ hybridization probe template: ACGCAATGGTGGTCTGGT | Allen Brain Atlas | https://developingmouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/100054743 |

| Reverse primers for Wnt7b in situ hybridization probe template: AAGGGCCTGAGGAAATGG | Allen Brain Atlas | https://developingmouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/100054743 |

| Forward primers for VP16: gatcggatccgccgccaccatgg cccccccgaccgatgtcagcct | This Paper | N/A |

| Reverse primers for VP16: gatcgatatccccaccgtactcgtcaattccaa | This Paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGEM-T Easy Vector System | Promega | A1360 |

| pCAG-Fezf2 | Chen et al., 2008 | University of California, Santa Cruz |

| pCAG-Fezf2-EnR | This Paper | N/A |

| pCAG-Fezf2-VP16 | This Paper | N/A |

| pCAG-EGFP | Matsuda and Cepko, 2004 | Addgene #11150 |

| pCMV-Tle4-Myc-DDK tag | This paper | Origene #MR231124 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FIJI | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://imagej.net/Fiji |

| Adobe Illustrator | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html |

| Adobe Photoshop | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html |