Abstract

Since its creation in the 1980s, transcranial Doppler (TCD) has provided a method of non-invasively monitoring cerebral physiology and has become an invaluable tool in neurocritical care. In this narrative review, we examine the role TCD has in the management of the moderate and severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) patient. We examine the principles of TCD and the ways in which it has been applied to gain insight into cerebral physiology following TBI, as well as explore the clinical evidence supporting these applications. Its usefulness as a tool to non-invasively determine intracranial pressure, detect post-traumatic vasospasm, predict patient outcome, and assess the state of cerebral autoregulation are all explored.

Keywords: cerebral autoregulation, multi-modal monitoring, transcranial doppler, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major global health concern with significant social and economic implications. It has become a leading cause of mortality and morbidity globally, and among young people in developed countries, it is the number one cause of death and disability.1 Unfortunately, the last 25 years have not seen a significant improvement in outcomes for patients following severe and moderate TBI, despite development of guideline-based management.2 This has led to increased interest in advanced multi-modal monitoring of these patients with the aim to advance the care of these patients in the acute phase.3,4

One such tool—and the topic of this review—is transcranial Doppler (TCD). TCD has become a commonly used tool in the management of TBI with one recent study finding it the second most commonly used form of bedside intracranial monitoring behind intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring, with 40% of neuro-intensive care units surveyed incorporating them into management.5 TCD, along with near-infrared spectroscopy, were found to be the most commonly used non-invasive methods of monitoring TBI patients in a recent systematic review.6

In this narrative review, the utility of TCD in the management of moderate and severe TBI patients in the acute period will be explored. The aim is to provide the reader with a better understanding of the scope of applications of TCD in this patient population and the level of supporting evidence.

History and Basics of TCD Application

Historical development of TCD

In the mid-1800s, the mathematician and physicist Christian Andreas Doppler first observed that when soundwaves of a certain frequency struck an object in motion, they are reflected with a different frequency.7 When the object is moving towards the source of the soundwaves, the echo will be of a higher frequency, while if the object is moving away from the source, the echo will be of a lower frequency. This became known as the Doppler effect. The difference in frequency of emitted versus the reflected sound wave is known as the Doppler shift and is proportional to the relative speed of the object to the source.

As red blood cells (RBCs) flow through a vessel, they reflect ultrasonic waves and the resultant Doppler shift can be used to infer a flow velocity of blood through that vessel. In 1972, Reid and Spencer leveraged this principle to develop the first ultrasonic Doppler flow probe.8 The ability of Doppler ultrasound to insonate basilar intracranial blood vessels transcranially was first reported by Aaslid and colleagues in 1982.9 In a study of 50 health patients, the anterior cerebral arteries (ACA), middle cerebral arteries (MCA), and posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) were insonated. The intracranial carotid arteries (ICA) or vertebral arteries (VA) were not insonated in this early study. The ability to determine cerebral blood flow velocities (CBFVs) non-invasively at the bedside gave TCD a distinct advantage over other techniques. This soon led to the first clinical application of TCD to detect cerebral vasospasm in patients following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).10

Basic principles of TCD

To better understand the applications and limitations of TCD, it is important for the reader to understand some of the basic principles of TCD. TCD ultrasound probes functions by emitting an ultrasonic wave at a known frequency (fo) and travels through the tissue at a speed (c). The wave then reflects off the moving RBCs in the vessel of interest and produces an echo at a different frequency (fe). This Doppler shift in frequency allows for the calculation of velocity (v). Notably, velocity needs to be corrected for by the angle of insonance (θ). While the actual angle of insonance cannot be determined at the bedside mathematically, we can see that as long as the angle of insonance is less than 30°, the degree of error will be less than 15%.

Equation 1

From Equation 1, the reader can see that the information gleamed from TCD is only applicable directly to determine CBFV, and not to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF) proper. The relationship between CBF and CBFV is linear over physiologic ranges, so long as vessel diameter is constant. If CBF is constant and vessel diameter is decreased, CBFV will increase as is seen in cerebral vasospasm.10 Fortunately, a study by Giller and colleagues11 showed that in 12 patients undergoing craniotomy, the diameter of larger cerebral vessels (ICA, MCA, and VA) changed less than 4% with modulation of arterial blood pressure (ABP) and end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2). Of interest, smaller vessels (distal MCA and ACA) saw a more substantial change in their CBFV as ABP and ETCO2 (21-29%).

The insonation of intracranial vessels takes advantage of three naturally occurring acoustic windows in the cranium. These are areas where bone thickness is sufficiently low to allow for transmission of ultrasonic waves. The transtemporal window can be used to study the ACA, MCA, and PCA. The transorbital window can be used to insonate the ophthalmic artery and the cavernous portion of the ICA. Finally, the transforminal window can be used to examine the basilar artery (BA) and VA.7 While most patients have adequate acoustic windows, 17% may not, limiting the utility of TCD. This appears to be an age-related phenomenon, with failed insonation occurring more frequently in those with advanced age.12 Figure 1 provides an illustration of the common insonation windows for TCD, with the underlying captured vessels.

FIG. 1.

Typical transcranial Doppler ultrasound windows and the vessels of interest. An overview of the windows can be seen in (A). The transorbital window is seen in (B), with the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), ophthalmic artery (OpA), and the internal carotid artery (ICA) labeled. The transforaminal window is seen in (C), with the vertebral artery (VA) and basilar artery (BA) labeled. Final the transtemporal window is seen in (D), with the ACA, ICA, and middle cerebral artery (MCA) labeled.

Parameters of TCD

There are two main parameters derived from Doppler ultrasound. The first is the flow velocity (FV) and the second is the pulsatile index (PI). The FV can be described in three distinct ways that are analogous to ABP. The peak systolic flow velocity (FVs) is the peak velocity from the TCD waveform, while the end diastolic velocity (FVd) is the trough. The mean velocity (FVm) is defined as (FVs +2FVd)/3. Figure 2 demonstrates the typical output of a TCD.

FIG. 2.

The typical output of a transcranial Doppler (TCD) as recorded on a Delica EMS 9D robotic TCD device (Delica EMS 9D System, Shenzen Delica Medical Equipment Co. Ltd, China). Note that the peak of the waveform is the systolic flow velocity (FVs) and is approximately 55 cm/sec. The trough of the waveform is the diastolic flow velocity (FVd) and is approximately 25 cm/sec. The mean flow velocity (FVm) would then be expected to be around 35 cm/sec.

The PI was described by Gosling and King in 1974 and is a unitless index defined as (FVs - FVd)/FVm.13 Since the PI is a ratio of FV, the effect of angle of insonation is effectively cancelled out thereby reducing the inter-measurement variability. PI was initially thought to represent cerebrovascular resistance (CVR) in TCD, but this has been called into question, as will be discussed later in this review.

Utility of Raw TCD Parameters in TBI

Much of the early work utilizing TCD in TBI was based around assessing the prognostic utility of direct TCD parameters FV and PI. In the sub-sections below, we review the literature around the clinical utility of these parameters.

FV in TBI monitoring

One of the earliest such studies was reported by Chan and colleagues, in which they examined the FV through the MCA in 121 TBI patients (50 severe, 16 moderate, and 55 mild) and compared them with normal controls.14 They noted that admission FV was lower in severe (35.8 cm/sec, 95% CI: 31.9-39.7), moderate (45.5 cm/sec, 95% CI: 40.0-51.0), and minor TBI (51.7 cm/sec, 95% CI: 47.9-55.5), compared with normal controls (60.1 cm/sec, 95% CI: 56.9-63.3). Of note, those with severe TBI not only had lower admission FV compared with moderate and mild TBI patients, but their velocities also remained pathologically low at discharge (46.2 cm/sec, 95% CI: 43.2-49.0). This impact of a prolonged period of reduced FV was also identified at 6-month follow-up with those with a good recovery or only moderate disability after a severe TBI, having had a significant increase in FV from admission (36.2, 31.5-41.1) to discharge (47.8, 43.7-51.9). However, those with a severe level of disability at 6 months, had FV that remained low even at the time of discharge. Concordant with this, 80% of patients with a FV <28 cm/sec died. This early evidence associated persistently low FV with poor outcomes.14

The implications of low FV were examined by a study of 57 severe TBI patients reported by van Santbrink and colleagues in which TCD measurements of FV in the MCA were made over the first 10 days of admission.15 They defined a low FV as <35 cm/sec and found that 63% of patients had a period of low FV during the monitored period. Most were observed in the first 8 h of monitoring. They also established that occurrences of low FV were associated with 6-month Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS; OR = 3.9, 95% CI: 1.2-13; p < 0.05) by a linear logistic regression model. However, this association was no longer significant when corrected for Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), age, presence of traumatic SAH, and computed tomography (CT) classification.15 As such, low FV may then be reflective of severe injury but may not be an independent predictor of outcome. Regardless, this association between low FV and outcomes may be mediated through cerebral hypoxia, as was found in a study of 17 TBI patients TCD and invasive brain tissue oxygenation (PbtO2) monitoring. In the study, 29 episodes of cerebral hypoxia, defined by PbtO2 < 20 mm Hg, were recorded. They noted that episodes occurring in the first 24 h were all associated with FVm <40 cm/sec in the ipsilateral MCA. However, over the course of the entire monitoring period, this association broke down.16 Findings here suggest TCD may then have a useful role as a non-invasive means of detecting early cerebral hypoxia, but these findings do require further validation.

While the effects of low FV following TBI were being established, Zurynski and colleagues found that elevated FV may be linked to adverse outcomes.17 In their report, TCD was used to determine FV in 50 patients following severe TBI. At admission, 35 of these patients were found to have abnormally elevated FV, and 15 were deemed to be not associated with vasospasm but rather were due to hyperemia. This group of 15 patients had the highest ICPs and lowest cerebral perfusion pressures (CPP), and only 47% of these patients had a good outcome at follow-up. When compared with those with normal FV, in which 87% had a good recovery, it would appear that hyperemia, as detected by TCD, is also associated with poor outcomes following TBI.17 In corollary, a recent study of 170 TBI patients found that in those without intracranial hematomas, CBF (as measured by perfusion CT) correlated weakly with FV as measured by TCD (R = 0.28; p = 0.0149 on the left side; R = 0.382; p = 0.00075 on the right side).18

PI in TBI monitoring

Despite some of the promising findings related to FV monitoring in TBI, its utility is limited and has been mostly abandoned as an isolated metric in acute TBI management. With significant variability imparted by its dependence on angle of insonance, FV is now often used in combination with other metrics to evaluate moderate and severe TBI patients. One such parameter, described previously, is the PI. Given that it is independent of the angle of insonance, it has long been felt to be a much more promising metric. Once thought to be directly reflective of CVR, animal studies have found that PI correlated positively with CVR, as measured with laser Doppler, when modulated with changes in arterial CO2 (R = 0.77; p < 0.0001), but correlated negatively when CVR was modulated with changes in CPP (R = -0.84; p < 0.001).19 This study points to a more complex relationship between PI and CVR.

The strong correlation between PI and CPP has been well established. Chan and colleagues had previously reported that in a study of 41 severe TBI patients when CPP was less than 70 mm Hg, there was a strong negative correlation between CPP and PI (R = -0.942; p < 0.0001).20 This link between PI and CPP may be the basis of the prognostic utility of PI and not its association with CVR. A study performed by Moreno and colleagues in 125 severe TBI patients found that PI measured by TCD within the first 24 h following injury was predictive of GOS at 6-month follow up, with patients with good outcomes having a mean PI of 1, while those with a poor outcome had an average PI of 1.56 (Student's t-test p < 0.0001).21 In this study, CPP and PI were also negatively correlated. Notably, FV was also lower in those with a poor outcome compared with those with a good outcome (36 cm/sec vs. 44 cm/sec; p < 0.003).21

TCD measurements of PI and FV as an assessment of cerebral perfusion has been leveraged in combination to predict outcomes. Zeigler and colleagues performed serial measurements of PI and FV in 255 severe TBI patients over their first week of admission.22 They defined hypoperfusion as two of FVm <35 cm/sec, FVd <20 cm/sec, and/or PI >1.4. In their cohort, 72 patients met these criteria during at least one measurement period and of those 71 died. Overall, abnormal TCD measurements, representing either hypoperfusion or hyperemia, seem to have a significant long-term prognostic value in TBI. A meta-analysis of five studies including 713 patients performed by Fatima and colleagues found that an abnormal TCD following TBI had an almost 4-fold higher likelihood of having a poor clinical outcome when compared with those with a normal TCD following their injury (OR = 3.87, 95% CI: 2.97-5.04; p < 0.00001).23 Here, an abnormal TCD included either signs of hyperemia (FVm >120 cm/sec) or hypoperfusion (FVm <35 cm/sec and PI >1.2). Mortality was also almost 10-fold more likely in those with an abnormal TCD (OR = 9.96, 95% CI: 4.41-22.47; p < 0.00001).

Prediction of secondary neurological decline

TCD may have a role in identifying those patients that may experience a secondary neurologic decline following a TBI. In a prospective cohort study of 42 patients with mild TBI and 36 patients with moderate TBI, Jaffers and colleagues measured PI while the patients were in the emergency department and then followed up 7 days later.24 At follow up, seven of the mild TBI and 10 of the moderate TBI patients had a secondary neurologic deterioration. Those that deteriorated had a significantly higher PI in both the mild (1.24 vs. 1.04; p < 0.01) and moderate (1.64 vs. 1.24; p = 0.05) TBI. Of note, FV was not found to be significantly different. This work was built on by Bouzat and colleagues,25 who identified cutoffs in FVd (25 cm/sec, sensitivity 92%, specificity 76%) and PI (1.25, sensitivity = 90, specificity 91%) for the increased likelihood of secondary neurologic decline using a cohort of 98 patients with mild and moderate TBI. They then followed this up with a multi-center prospective observational study of 356 mild and moderate TBI patients in which they tested these thresholds.26 In their cohort, 20 patients (6%) developed a secondary neurologic decline. Their TCD thresholds had 80% sensitivity (95% CI: 56-94%) and 79% specificity (95% CI: 74-83%) to predict neurologic worsening. A predictive model including age, GCS, and TCD abnormality was also successfully developed (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.82-0.89; p < 0.01).

Utility in treatment direction

Direct TCD parameters have an established prognostic role in TBI but there is a growing body of evidence that they may also be used to guide management. In a retrospective study, Chang and colleagues examined the influence TCD monitoring had on clinical outcomes.27 Thirty TBI patients with ICP and TCD monitoring were compared with a historical control of 30 patients with just ICP monitoring. Their management protocols distinguished patients in states of hypoperfusion, vasospasm and hyperemia as determined by TCD parameter of FV and PI. While there was no difference in mortality in the groups, 6-month follow-up found a significant difference in the proportion of patients with a favorable outcome as defined as an extended GOS (GOSE) >4 (42.9% in the ICP group vs. 70.4% in the ICP and TCD group, OR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.1-0.96; p = 0.043).27

In general, the evidence behind the utility of direct TCD parameters, FV and PI, in driving clinical management following TBI is in its early stages. Interest is growing, however, as evidenced by its rapid adoption. Key limitations include the inter-operator variability and the lack of familiarity with interpretation of these parameters. Strong evidence in the form of prospective randomized control trials will likely be needed to establish the advantage of these parameters in TBI over and above those found by ICP and CPP monitoring.

TCD to Detect Cerebral Vasospasm in TBI

The utilization of TCD in TBI as discussed thus far has assumed stable vascular diameter. As mentioned earlier, changes in CBF can be inferred from changes in FV only if the diameter of the vessel of interest remains constant. That is because for a given CBF, if vessel diameter is reduced FV will increase and this can be seen in the setting of cerebral vasospasm. Aaslid and colleagues first described TCD to detect cerebral vasospasm in the setting of aneurysmal SAH.10 At that time, they defined vasospasm as a FV in the MCA >120 cm/sec as measured by TCD. In the following sub-sections, we will explore the utility of TCD to detect post-traumatic vasospasm (PTVS), which occurs in 30–40% of patients with severe TBI and is associated with poor outcomes. It can occur as early as 3 days post-injury and can last up to 5 to 10 days. Young age, low admission GCS, and traumatic SAH have all been shown to be risk factors for PTVS.28 Below we outline two methods of detection by TCD, and the pertinent literature.

Vasospasm detection by FV

Detection of PTVS by TCD was first reported by Compton and Teddy29 in a study of 25 TBI patients. They used a FV based method and defined PTVS as a FV >100 cm/sec. They found 17 of the patients developed PTVS by their definition, while 12 of the instances of elevated FV were associated with neurologic deterioration. The role of TCD at detecting PTVS causing impaired CBF was further enforced by a study of 30 TBI patients reported by Martin and colleagues.30 In their study, they defined PTVS by a FV in the MCA >120 cm/sec and severe PTVS as a FV of >200 cm/sec in the MCA. In their cohort, eight patients were found to have PTVS, with three having severe spasm. All cases of severe PTVS were associated with the presence of traumatic SAH. Interestingly, they also found that peak FV was correlated with the lowest CBF as measured by a Xe133 technique. The time course of FV was examined in a study of 86 moderate and severe TBI patients by Steiger and colleagues.31 They noted that during the first three days, ICA and MCA FV were depressed but then increased to a maximum between day 5–7 with an increase in velocities in the MCA being more pronounced than those in the ICA. Interestingly, the amount of SAH on CT was correlated with average velocities (R = 0.5; p < 0.05).

The prognostic utility of TCD derived FV to detect PTVS was the subject of a meta-analysis by Fatima and colleagues.23 Incorporating five studies with a total of 713 TBI patients, they found that FV >120 87cm/sec in the MCA was associated with a three-fold higher likelihood of poor functional outcome (OR = 3.64; 95% CI: 1.55-8.52; p = 0.003). This study, however, points to a limitation of FV based assessments of PTVS. The presence of elevated FV does not distinguish between hyperemia and vasospasm. While both can result with adverse outcomes following TBI, their management is vastly different as hyperemia represents excess CBF while vasospasm reflects inadequate CBF.

Vasospasm detection by Lindegaard ratios

The most popular method of distinguishing between hyperemia and vasospasm was first described by Lindegaard and colleagues by taking the ratio of FV in the MCA to that in the ICA.32 In the setting of hyperemia, both ICA and MCA FV will be high and so the ratio will be low. In the setting of vasospasm, MCA FV due to narrowing and ICA FV will be low because of increased downstream resistance, this results in an elevating Lindegaard ratio (LR).

Weber and colleagues reported a study of 35 patients with severe TBI in which 14 were found to have PTVS as defined by a LR >3.33 While the onset of PTVS was as early as 48 h post-injury, most were between 5 to 7 days post-injury. In a later study, Zurynski and colleagues reported on the prognostic importance of distinguishing between PTVS and hyperemia in a study of 50 severe TBI patients that had FV monitored by TCD.17 In their cohort, 35 patients developed FV >100 cm/sec and of these, 20 were deemed to be in spasm due to having a LR >3. In this group, only 40% had good outcomes at follow up. The remaining 15 were deemed to have hyperemia and had the highest ICPs and lowest CPPs with 47% having a good outcome. Notably, in those patients that had normal FV, 87% obtained good outcomes. Ziegler and colleagues highlighted a similarly grim prognosis for those with PTVS in a study of 255 TBI patients.22 They defined PTVS as a FV >120 cm/sec and a LR >3 and had 69 patients who met these criteria of which 55% either died or were severely disabled.

TCD to Derive ICP and CPP in TBI

There have been many attempts to leverage TCD to gain insights into cranial pressure dynamics non-invasively. Shortly after the development of TCD, Aaslid reported on 10 patients that underwent ventricular infusion testing for hydrocephalus while being monitored by TCD.34 They found a relatively good concordance between their estimation of CPP by TCD and actual CPP as measured invasively. In particular, they were able to differentiate between low and normal CPP 100% of the time. This sparked much interest in evaluating TCD as a means of non-invasively measuring ICP and CPP. In the setting of TBI, as mentioned previously, direct parameters of TCD can be difficult to interpret. However, if these parameters could somehow be translated into estimates of ICP and CPP, then their incorporation into established guideline-based management would be facilitated and adoption of TCD as a routine monitoring device may become widespread. In the following sub-sections, we review the evidence for TCD as a non-invasive means of monitoring intracranial pressure dynamics in TBI.

ICP

Conceptually, linking ICP to TCD parameters is not difficult. In pathologic states such as TBI, the main opposing force to CBF is ICP. Since FV is thought to be linearly related to CBF, so long as vessel diameter is constant, then FV tracings should contain some encoded information about ICP. Practically speaking, decoding this information has not been perfected. One early example was reported by Goraj and colleagues in a study of 12 TBI patients with invasive ICP monitoring.35 They found that the reactivity index (RI) as measured by TCD and defined as (FVs - FVd)/FVs was correlated to measured ICPs (R = 0.6062; p < 0.05). As ICP increases, the FVd decreases more substantially than the FVs, and therefore we would expect ICP to be proportional to the difference in FVs and FVd. This difference is scaled by dividing by FVs. (In other studies, PI is used and so the difference is scaled by dividing by FVm.) Subsequent studies have attempted to build on this concept by incorporating more variables into their estimates of ICP. In a study of 39 TBI patients, a predictive model of ICP from PI was augmented with hematocrit (Hct), mean atrial blood pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR) and PaCO2. While a correlation was found, it was still weak (R = 0.43; p < 0.0001). From their analysis, incorporation of MAP and HR improved the predictive value while PaCO2 and Hct did not.36

More complex methods have been developed to estimate ICP in TBI patients using TCD. One such method utilized analysis from an RC-circuit analog in which ABP was analogous to voltage, CBF to current, CVR to resistance, and compliance of the cerebral vasculature as an analog to capacitance. In 37 TBI patients with 39 h of recording time, Kashif and colleagues estimated ICP with a mean error of 1.6 mm Hg and a standard error of 7.6 mm Hg.37 When incorporating measurements of both MCAs, mean error was brought down to 1.5 mm Hg with a standard error of 5.9 mm Hg. In another study, Schmidt and colleagues utilized a method of determining a noninvasive ICP using an impulse response function that is modified based on updated TCD parameters and ABP.38 In 137 severe TBI patients with 315 recordings, they found the absolute difference between ICP and their estimate was 4.9 mm Hg with a standard deviation of 3.3 mm Hg.

In a prospective comparative study, Cardim and colleagues39 found that in their cohort of 40 TBI patients a “black box” estimator of ICP based on the interactions between TCD and ABP, like the one described above by Schmidt and colleagues, was the best estimator of ICP as a number (R = 0.39; p < 0.05). Interestingly, they also found that an estimator of ICP based on PI was the best at predicting changes in ICP (R = 0, 61; p < 0.05). Estimate of ICP based of FVd, however, had a large 95% CI of almost 15 mm Hg. In a follow up study of 27 TBI patients, the same group found that while these methods had inadequate accuracy of predicting ICP, they did have a good ability to detect intracranial hypertension with the “black box” method being the best with an area under the receiver/operator curve of 0.82. Once again, the FVd was found to be the worst (AUC = 0.77).40

Finally, a more computationally intensive method of estimating ICP from TCD measurements involves determining the critical closing pressure (CrCP). In the cerebral circulation, the critical closing pressure is the pressure at which small vessels can collapse and is often defined as the sum of ICP and tension of the arterial walls. CrCP can be calculated by identifying the x intercept of a regression line for a FV vs. ABP plot as is demonstrated schematically in Figure 3. In an early study of 98 TBI patients, Czosnyka and colleagues found a mild correlation between CrCP and ICP (R = 0.41; p < 0.0002).41 A much better correlation was found by Buhre and colleagues in a study of 20 severe TBI patients where CrCP correlated will with ICP (R = 0.93; p < 0.05).42 Notably, the average ICP in the study was quite high (34.7, standard deviation = 17.8) and it would appear from the Czosnyka and colleagues' data that as ICP increases, the predictive ability of CrCP improves. This may be explained by the fact that at lower ICPs, the ICP does not actually represent the effective downstream pressure as resistance to flow is predominantly determined by vascular tone.42

FIG. 3.

A schematic representation of the derivation of critical closing pressure (CrCP). Flow velocity (FV) is plotted against arterial blood pressure (ABP) and the x intercept, which the ABP at which FV is zero, represents the CrCP.

Estimates of ICP based on TCD currently have far too large an error to effectively replace invasive monitoring as a means of determining minute to minute ICP measurements. They are not entirely without clinical utility, as they are sensitive to episodes of elevated ICP and may become a useful way of determining and managing ICPs when invasive ICP measurements are not available or risky to obtain such as in coagulopathic states. Further work is ongoing in this area of TCD application to improve ICP estimation.

CPP

With the current error in measurements of ICP not within clinically acceptable limits, a significant focus has been placed on the possible use of TCD as a method of determining CPP non-invasively. The rational being that while a 5 mm Hg error in ICP may be significant clinically, an error of similar magnitude in CPP is not nearly as significant. Early research by Chan and colleagues had shown good correlation in 41 TBI patients between PI and CPP when CPP was below 70 mm Hg (R = - 0.942; p < 0.0001).20 Notably there was no correlation between CPP and PI when CPP was above 70 mm Hg. The use of PI as an estimator of CPP was further evaluated by Zweifel and colleagues in a population of 290 TBI patients with almost 500 h of recording.43 They found that while there was a correlation with PI and CPP (R = -0.41; p < 0.001), the correlation was weak. More importantly, the 95% prediction interval of CPP, for a given PI, was more than ±25 mm Hg. PI may then be thought to be a good estimator of low CPPs but does not reliably predict CPP so as to be an adequate non-invasive replacement.

With the realization that PI was limited in its ability to estimate CPP, Czosnyka and colleagues developed an estimate of CPP (eCPP) that incorporated MAP (Equation 2).44 In a population of 96 moderate and severe TBI patients requiring invasive ICP monitoring, they evaluated the performance of eCPP against invasive CPP. They found a correlation between the two that was robust (R = 0.71; p < 0.000001) and in 71% of cases, the error was less than 10 mm Hg. Their method also had a high predictive value (94%) of detecting low CPP as defined as less than 60 mm Hg. As a method of solely detecting changes in CPP, it performed even better (R = 0.81; p < 0.001). Further analysis identified that the maximum likelihood estimator could be evaluated as seen in Equation 3.44 Follow up work reported by Schmidt and colleagues evaluated the predictive ability of the maximized predictor of CPP in 25 TBI patients.45 They found 81% of the 1-min averages of the modified eCPP were different from direct CPP by less than 10 mm Hg indicating that their method of estimation may be clinically useful is settings where invasive measure of ICP is not available.

Equation 2

Equation 3

To improve accuracy, Varsos and colleagues reported on an impedance-based method of calculating CrCP from ABP and FV.46 They then incorporated this into an estimator of CPP. In a cohort of 48 severe TBI patients, they were able to find a good correlation between CPP and their estimate (R = 0.851; p < 0.001). As has been seen with previous methods, they were able to accurately predict low CPP, as defined as less than 70 mm Hg, with good accuracy (AUC = 0.913, 95% CI: 0.883-0.994; p < 0.01).

From the evidence, the role of TCD in estimation of CPP seems to be limited. It does not reliably predict CPP with a great enough accuracy to replace invasive means in a TBI population. There seems to be consistency in the literature that TCD based measurements of CPP are able to detect low CPP in the setting of TBI. No trial has sought to examine if management based on measurements of invasive CPP outperform management based on measurement made non-invasively with TCD in a TBI population. The evidence around the CPP guided management in TBI is not robust and so clinical equipoise might be argued.

One setting in which non-invasive estimates of TCD may be advantageous is in the pre-hospital/pre-tertiary care setting. Early in management, when invasive monitoring is not available, non-invasive measurements of CPP may inform care. In a prospective study of 18 severe TBI patients, TCD was used to determine if a state of abnormal cerebral perfusion was present prior to insertion of an ICP monitor. Abnormal cerebral perfusion was defined as a PI >1.4 and a low FVd. Mannitol and norepinephrine were administered to improve cerebral perfusion once deemed abnormal. Of the 18 patients, nine had abnormal cerebral perfusion and nine had normal perfusion. Notably, there was no significant difference in GCS or MAP between the two groups. Of the patients with abnormal perfusion, four had pupils that were bilaterally fixed and dilated. In five of the abnormal perfusion patients, TCD parameters were normalized with management including two that saw reversal of pupillary abnormalities. Among the five that saw correction of their TCD findings, two died within 48 h while all four that could not have their TCD metrics corrected died within 48 h. None of the patients with normal cerebral perfusion required surgery while three of those with abnormal findings did.47 Much more work needs to be done before TCD based early management of TBI patients can become routine, but this small study does show promise.

TCD to Evaluate Cerebral Autoregulation in TBI

Cerebral autoregulation (CA) was first described initially in animals by Fog48 and was later reported on in humans by Lassen.49 CA is the tendency of CBF to remain constant over a range of MAP. For CPPs below the lower limit of autoregulation (LLA), autoregulatory mechanisms are unable to maintain adequate CBF and ischemia is present. At CPPs above the upper limit of autoregulation (ULA), autoregulatory mechanisms are overwhelmed and hyperemia occurs. However, at CPPs between the LLA and ULA, CBF is adequate and relatively stable.48,49 The early evidence of the disruption of CA in patients with moderate and severe TBI came from Overgaard and Tweed in the 1970s.50 They reported on a study of 43 TBI patients in which they assessed CBF by Xe133 dilution methods while they pharmacologically manipulated MAP. They found that CA was often impaired in the early period following TBI. Utilizing similar methods, Cold and Jensen demonstrated that in a population of 18 comatose patients with TBI, 83% had impaired CA with a trend towards normalization after 5 days post-injury.51 Much of the early examination of CA in TBI required such static measures of CA. They obtained measurements of CBF at equilibrium following modulation, often pharmacologic, of MAP. These methods were limited in their temporal resolution and as a result, limited their ability to comment on changes of CA over time.

With the advent of TCD and the ability to measure FV as a surrogate of CBF, assessments of CA could now be done at the bedside. These opened the door to assessments of dynamic CA as the temporal resolution of TCD was far superior to that of previous methods. In the sub-sections to follow, we examine TCD as a method of evaluating the state of CA in TBI patients in an intermittent and semi-intermittent manner. We focus on two categories of CA monitoring methods using TCD, intermittent and semi-intermittent. The terms intermittent, semi-intermittent, and continuous refer to the frequency at which that assessment of CA is updated. The practical limit of TCD monitoring time being limited to under 1 h restricts TCD based methods to intermittent and semi-intermittent measurements. Table 1 outlines the intermittent techniques, while Table 2 outlines the semi-intermittent methods. The subsequent sections do not provide and exhaustive list of all the means by which TCD has been described to evaluate CA. Here, we aim to provide a description of the methods that have been used in TBI cohorts. For both the techniques described here, and others in the literature, we refer the interested reader to those parent papers for more details.

Table 1.

Summary of Transcranial Doppler (TCD)–Based Intermittent Techniques of Assessing Cerebral Autoregulation (CA)

| Intermittent method | Method of cerebral perfusion perturbation | Normal value(s) | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of regulation (RoR) | Thigh cuff deflation | 0.2/sec | • Good signal-to-noise as perturbation induced • Computationally simple |

• Requires induced transient reduction in ABP • Possible risk in those with unstable hemodynamics |

| Autoregulatory index (ARI) | Thigh cuff deflation | 4-7 | • Good signal-to-noise as perturbation induced • Defined normal CA values |

• Requires induced transient reduction in ABP • Possible risk in those with unstable hemodynamics • Computationally complex |

| Transient hyperemic response testing (THRT) | Carotid compression | >10% overshoot | • Good signal-to-noise as perturbation induced • Avoids systemic ABP fluctuation • Computationally simple • Ability for isolated hemispheric assessment |

• Requires transient reduction and overshoot in carotid flow. • Risk of stroke in those with carotid atherosclerotic disease |

| Orthostatic hypotension test (OHT) | Rapid change in patient head position | 10 to15% | • Good signal-to-noise as perturbation induced • Computationally simple |

• Requires induced transient reduction in ABP • Possible risk in those with unstable hemodynamics • Requires rapid (<3 seconds) change in patient position |

ABP, arterial blood pressure.

Table 2.

Summary of Transcranial Doppler (TCD)–Based Semi-Intermittent Techniques of Assessing Cerebral Autoregulation (CA)

| Index | CBF surrogate | Driving pressure surrogate | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mx | FVm | CPP | • Shown to discriminate between survival and death following TBI • Shown to discriminate between favorable and unfavorable outcome following TBI |

• Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Requires invasive ICP monitoring |

| Sx | FVs | CPP | • Shown to discriminate between survival and death following TBI • Shown to discriminate between favorable and unfavorable outcome following TBI • Shown to covary with PRx |

• Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Requires invasive ICP monitoring |

| Dx | FVd | CPP | • Shown to discriminate between favorable and unfavorable outcome following TBI | • Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Requires invasive ICP monitoring |

| Mx_a | FVm | MAP | • Does not require invasive ICP monitoring • Shown to discriminate between favorable and unfavorable outcome following TBI • Can be used to estimate PRx |

• Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Less studied than CPP based indices |

| Sx_a | FVs | MAP | • Does not require invasive ICP monitoring • Shown to discriminate between survival and death following TBI • Shown to discriminate between favorable and unfavorable outcome following TBI • Shown to covary with PRx • Can be used to estimate PRx |

• Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Less studied than CPP based indices |

| Dx_a | FVd | MAP | • Does not require invasive ICP monitoring | • Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Less studied than CPP based indices |

| TF-ARI | Full CBFV waveform | Full ABP or CPP waveform | • Defined normal CA values • Can be performed with or without invasive ICP monitoring |

• Requires long recording periods due to poor signal-to-noise • Computationally complex |

CBF, cerebral blood flow; Mx, mean flow index with cerebral perfusion pressure; FVm, mean flow velocity; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; TBI, traumatic brain injury; ICP, intracranial pressure; Sx, systolic flow index with cerebral perfusion pressure; FVs, systolic flow velocity; Dx, diastolic flow index with cerebral perfusion pressure; FVd, diastolic flow velocity; Mx_a, mean flow index with arterial blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PRx, pressure reactivity index; Sx_a, systolic flow index with arterial blood pressure; DX_a, diastolic flow index with arterial blood pressure; TF-AR, transfer function autoregulatory index; CBFV, cerebral blood flow velocity; ABP, arterial blood pressure; CA, cerebral autoregulation.

Intermittent methods

Rate of regulation

One of the earliest means of assessing dynamic CA in an intermittent fashion was described by Aaslid and colleagues and was termed the thigh cuff deflation technique (TCDT).52 In their seminal work, they induced an acute step decrease in ABP by rapidly deflating a thigh BP cuff that had previously been inflated above the subject's systolic BP for 2 min. They then measured the time for the FV to return to its pre-deflation level and termed this the rate of regulation (RoR) with 0.2/sec considered as normal (Equation 4).52

Equation 4

Autoregulatory index

Tiecks and colleagues built on the RoR method and developed the autoregulatory index (ARI).52 They used a second order differential model of CA based on three physical properties: the time constant, the damping factor and the autoregulatory gain. A set of 10 parameter values were defined and an ordinal scale from 0 to 9 graded the strength of autoregulation. The TCD derived FV changes observed during the change in MAP are normalized and then compared with the model generated responses corresponding to the 10 grades to determine the best match and deemed to be the ARI. Here, 0 corresponds to complete loss of autoregulation, and 9 to hyperactive regulatory response. Normal CA is defined as an ARI of 4 to 7, and abnormal 3 and below.53

In a prospective study of 122 patients with severe TBI, Hlatky and colleagues determined the ARI every 12 h for the first 5 days post-injury and then once daily for the following 5 days.54 They noted that ARI was on average abnormally low (2.8 ± 1.9) initially and continued to decrease to a nadir of 1.7 ± 1.1 between 36 and 48-h post-injury which is in keeping with other assessments of CA in severe TBI. Schramm and colleagues found a slightly later nadir of 4 days post-injury in their cohort of 16 patients.55 Sviri and colleagues found in their cohort of 36 severe TBI patients that 40% of those with a poor outcome had an ARI that failed to recover in the first 11 days after injury which underlines some prognostic utility to the ARI.56 In a follow-up study of 24 TBI patients, ARI testing was found to create only transient and relatively minor fluctuations in systemic physiologic measures as was therefore determined safe in this population.57

Transient hyperemic response testing

Another method of assessing dynamic CA in an intermittent manner using TCD was described initially by Giller.58 In this technique, the carotid artery is compressed in the neck while the ipsilateral MCA is insonated. Compression should result in a reduction in FV of 30-50% or baseline to be considered adequate. After 3 sec of stable reduction in FV, the carotid is released, and MCA FV are measured. This is known as transient hyperemic response testing (TRHT).58 In the setting of intact CA, CVR would have decreased to compensate for the reduced flow and once compression is released, an overshoot of at least 10% of baseline FVs is expected. Any overshoot less than 10% is thought to represent impaired CA.59 In a study of 47 TBI patients, Smielewski and colleagues performed THRT. They dichotomized their THRT results into positive and negative with a cutoff of 1.10 based on previous work done in healthy controls. They found that, in their study, population THRT was 1.11 (range 0.9-1.48). Those with a negative THRT more often had an admission GCS of <6 (14 vs. 9; p < 0.05) and more often had an unfavorable outcome by 6-month dichotomized GOS (16 vs. 5; p < 0.0004) demonstrating the prognostic utility of THRT.60

The primary limitation of intermittent methods of assessing CA is that they require eternal perturbations to that subjects' physiologic parameters. This in turn limits the frequency with which they can be performed. One advantage of this, however, is that there is a reasonable clarity that the changes in TCD signal are in reaction to the perturbation. While not widely used clinically, these methods have provided insight into CA in the setting of TBI.

Orthostatic hypotension test

A sudden change in head position can result in a sudden reduction in CPP. In the orthostatic hypotension test (OHT) the head position of the patient is rapidly elevated, over the course of less than 3 sec, and the resultant drop in CBFV is evaluated by TCD. A reduction of CBFV of between 10 and 15% is considered within the limits of normal with reductions of mor that 20% being indicative of disrupted autoregulation. The utility of this test in the setting of moderate and severe TBI is limit by the difficulty in rapidly moving these critically ill patients. This is reflected in the small number of studies utilizing this method to examine autoregulation in TBI patients.61,62 There is however some evidence that OHT weakly correlates with TCDT (r = 0.23; p < 0.05).61 Despite this, the cumbersome nature of this method will likely limit further clinical evaluation.

Semi-intermittent methods

In recent years, more continuous assessments of CA that leverage natural slow wave variations in CPP and MAP have been explored. In general, these methods work by having a regularly updating correlation coefficient between some surrogate of CBF and some measure of driving pressure over an advancing set time window. There are six different variations of these indices that are based on TCD FV. Mean flow index with cerebral perfusion pressure (Mx), systolic flow index with cerebral perfusion pressure (Sx), and diastolic flow index with cerebral perfusion pressure (Dx) use FVm, FVs, and FVd respectively as their surrogates for CBF and CPP is used to approximate the driving pressure. Alternatively, MAP is used to approximate driving pressure in the less invasive variants mean flow index with arterial blood pressure (Mx_a), systolic flow index with arterial blood pressure (Sx_a), and diastolic flow index with arterial blood pressure (Dx_a). Table 2 provides an overview of these six indices of cerebrovascular reactivity. In all of these, the FV and driving pressure is processed via a 10-sec moving average filter. The correlation coefficient is calculated using a 5-min window that is updated every 10 sec, or every minute, depending on recording length. The values of the index are correlation coefficients and are therefore normalized to values between −1 and +1, with more positive values representing more dysfunctional CA. These methods are designated semi-intermittent, because while theoretically they can continuously interrogate CA, practically the length of interrogation is limited by either the operator of the TCD or drift in probe mounting systems.19,63,64

Czosnyka and colleagues reported one of the earliest studies associating Mx and Sx with outcomes in TBI patients.19 In their cohort of 82 patients, they noted a correlation between 6-month GOS and both Mx (R = 0.41; p < 0.0002) and Sx (R = 0.48; p < 0.00009). In a follow-up study of 187 TBI patients, Czosnyka and colleagues found that in those with a favorable outcome, Mx was lower compared with those with an unfavorable outcome (-0.06 vs. 0.15; p < 0.00002).65 They also noted that when Mx was plotted against CPP for their cohort, a U-shaped curve was demonstrated. This indicated that both low and high CPPs may be associated with dysfunctional CA, in keeping with the concepts of ULA and LLA.65

TCD-based indices of CA have been shown to correlate with other methods of assessing CA in TBI patients. In a report on 298 TBI patients, Zweifel and colleagues found that there was a significant association between Mx and PRx (R = 0.36; p < 0.01).66 PRx, or pressure reactivity index, is an index that continuously evaluates cerebrovascular reactivity and has a large body of evidence supporting its prognostic value in TBI. It works by utilizing invasively measured ICP as a surrogate for cerebral blood volume (CBV)/CBF and evaluates its correlation with MAP to gain insight into the state of CA. PRx is also one of only two continuous indices validated in animal models with respect to its ability to detect the LLA.67 Similarly, Budohoski and colleagues found that in their cohort of 345 TBI patients, there was a moderate correlation between PRx and Mx (R = 0.58; p < 0.001).68 They noted that discrepancies were more pronounced in those with ICP >30 mm Hg. Additionally, they found that Mx was significantly lower within the first 24-h for those that survived than those that died.

One of the limitations of Mx, Sx, and Dx, is that since they incorporate CPP, they require invasive intracranial monitoring to derive CPP. MAP based indices have no such requirement and as a result much work has to be done to explore them as possible alternatives. In one such preliminary study of 151 TBI patients, Lewis and colleagues found that while Mx and Mx_a were similar when averaged over large groups of patients, they may be very different in individual cases.69 Budohoski and colleagues compared all six TCD based semi-intermittent indices in a study of 300 TBI patients.64 They found that death and survival were able to be discriminated against by Mx (F = 6.93; p = 0.009), Sx (F = 13.10; p = 0.0003), and Sx_a (F = 5.32; p = 0.02), with Sx having the best predictive value (AUC = 0.646, 95% CI: 0.569-0.722; p < 0.05). Favorable and unfavorable outcomes were able to be discriminated by Mx (F = 16.58; p = 0.00006), Sx (F = 20.11; p = 0.00001), Dx (F = 7.07; p = 0.008), Sx_a (F = 12.49; p = 0.0005), and Mx_a (F = 8.88; p = 0.003). Once again, Sx was found to have the best ability to distinguish between outcomes (AUC = 0.659, 95% CI: 0.595-0.722; p < 0.05). Of note Dx_a was not found to have any significant predictive value.64

More recently, in a study of 347 TBI patients, Zeiler and colleagues looked to confirm the covariance of TCD based indices, such as Sx and Sx_a, with ICP based indices of cerebrovascular reactivity, such as PRx.70 They found that Sx and Sx_a covary with ICP based indices. Sx displayed a threshold of -0.15 for unfavorable outcomes (AUC = 0.646; p = 0.001) and -0.2 for mortality (AUC = 0.630; p = 0.005). Sx_a had a threshold of 0.05 (AUC = 0.582; p = 0.068) for mortality and -0.10 for unfavorable outcome (p = 0.0001). Interestingly, in the same cohort, they went on to show that by leveraging linear mixed effects and Box-Jenkin's autoregressive integrative moving average (ARIMA) modelling, PRx can be estimated from Mx_a and Sx_a which strengthens the possibility of avoiding invasive ICP monitoring.71

While the previously described semi-continuous indices are based on time series analysis, emerging evidence is supporting the use of indices based on analysis of input and output variable in the frequency domain. The transfer function autoregulatory index (TF-ARI) leverages transfer function analysis to extract CBFV step responses to changes in ABP or CPP. This method provides a continuously updated ARI value limited in length by the practical aspects of TCD recording.72 The complex mathematics involved in this index is beyond the scope of this review, but the reader can find a detailed description in a recent review by the senior author.73 An early study by Panerai and colleagues found a significant correlation between TF-ARI and GOS in their cohort of 32 TBI patients (R = 0.464; p = 0.011).72 In a study of 50 TBI patients, Czosnyka and colleagues found a linear correlation between TF-ARI and Mx (R = -0.62; p = 0.001). TF-ARI was also found to be significantly higher in those with favorable outcomes compared with those with unfavorable outcomes (6.7 ± 1.68 vs. 5.1 ± 2.36; p = 0.016).74 The relationship between Mx and TF-ARI was redemonstrated by Lui and colleagues in a study of 288 TBI patients. They found that as significant correlation existed between the time and frequency-based indices regardless of if ABP or CPP was used as an input variable (R = -0.38; p < 0.001 and R = -0.404; p < 0.001, respectively).75 While TF-ARI is a promising new index additional research is needed before the role of indices based on frequency domain analysis can be fully understood.

There has been significant growth in the data supporting TCD based semi-intermittent indices for monitoring TBI patients. However, in clinical practice, their role is limited both by their resource intensiveness and by the lack of data showing that this monitoring can modify outcomes.

CO2 Reactivity

The cerebral circulation is exquisitely sensitive to changes in PaCO2 and CO2 manipulation if frequently utilized in the management of intracranial hypertension. TCD can be utilized to evaluate CO2 reactivity by assessing the change in CBFV as end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) changes.76 Because of its ability assess both cerebrovascular reactivity and CO2 reactivity, TCD has recently been leveraged in to examine the connection between these two physiologic parameters. Haubrich and colleagues examined how hypocapnia modifies Mx in 30 ventilated TBI patients.77 They found that in those with intact autoregulation, hypocapnia did not significantly change Mx from baseline (left: -0.23 ± 0.23; right: -0.21 ± 0.24) but in those with impaired autoregulation Mx was improved with hypocapnia (left: 0.37 ± 0.13; right: 0.33 ± 0.26 vs. left: 0.12 ± 0.25; right: -0.0003 ± 0.19; p < 0.01). Zhang and colleagues examined a cohort of 31 TBI patients that underwent 60 min of hyperventilation and found that TF-ARI was significantly increased following hyperventilation (5.31 vs. 4.33; p = 0.02).78 Further analysis also found a significant positive linear correlation between CO2 reactivity and TF-ARI (R = 0.41; p = 0.04). Further work is needed to better understand this relationship but in the future TCD may help guide PaCO2 driven manipulation of autoregulation in TBI patients.

Miscellaneous Physiologic Parameters Measured by TCD

The role of TCD in the assessment of physiologic parameters is ever expanding with new with new techniques being developed to leverage the non-invasive and rapid nature of TCD. In this section, we briefly describe some TCD based physiologic parameters that may soon find application in the research and clinical management of TBI patients.

Critical closing pressure/wall tension

As discussed earlier, critical closing pressure (CrCP), is the ABP at which small cerebral arteries collapse and blood flow stops. While described earlier in this text with regards to the non-invasive measurement of ICP, CrCP has become a physiologic metric of interest in its own right with research being performed to determine novel methods of determining it outside of the world of TBI.79,80 The concept of wall tension (WT) has also emerged as a closely related concept with it being the difference between CrCP and ICP and reflecting cerebrovascular tone. In a study of 280 TBI patients, Varsos and colleagues examined the relationship between CA, as measured by Mx and TF-ARI, and CrCP and WT as calculated using a cerebrovascular impedance method.81 They determined that impaired CA and low WT were associated with WT negatively correlating with Mx (R = -0.138; p = 0.021) and TF-ARI (R = 0.118; p = 0.048). No association was found between WT and outcomes following TBI. While its prognostic utility may not be clear, CrCP and WT may provide another valuable means of monitoring cerebrovascular physiology utilizing TCD.

Diastolic closing margin

When diastolic blood pressure is equal to CrCP cerebral blood flow only occurs during systole. The difference between dynastic blood pressure and CrCP has been termed the diastolic closing margin and is thought to be better indicator of cerebral perfusion than ABP or CPP. It has been reported as an effective method of assessing perfusion adequacy during surgery in the beach chair position and its elevation has been associated with intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants.82,83 Its applications to TBI in the literature is limited but it may find use as a measure of adequate but not excessive cerebral perfusion following TBI.

Cerebral compliance

The ability of the brain to adapt to changes in intracranial volume to maintain constant intracranial pressure is known as cerebral compliance (CC) can broadly take two forms. Cerebrovascular arterial compliance (Ca) is the change in arterial blood volume in response to changes in ABP. The compliance of the cerebrospinal space (Ci) is the change in volume in response to change in ICP. Ci is composed of the compliance of the cerebral venous bed and the craniospinal CSF spaces.84 Through analysis of pulsatile changes in ABP as well as ICP and the subsequent changes in cerebral arterial blood volume, as measured by TCD,85 Ca can be determined. Carrera and colleagues utilized these methods to analyze the effects of mild hypocapnia on 27 TBI patients.86 They found that hyperventilation corresponded to an increase in Ci (R = 0.213; p = 0.015) as ICP decreased and initial a reduction in Ca was also observed (R = 0.209; p = 0.017). This reduction in Ca following hyperventilation is proposed as a possible mechanism for the lack of benefit of hyperventilation following TBI. CC is a valuable TCD derived parameter that may provide further clinical insights into the management of TBI with ongoing exploration.

Future Directions

The future work in TCD based management of TBI can be divided by phases of care. There are roles for TCD in pre-hospital, acute care and in follow-up, but much work needs to be done before we see TCD used routinely in TBI management. In the pre-hospital and early hospital setting, the role of TCD as an evaluator of critically low CPP or high ICP must be further examined. While the data shows that ICP and CPP estimations, even with complex models, are not accurate the question becomes, in the period prior to invasive ICP monitoring, can it provide sufficient information to drive care. This can be tested in a randomized fashion as there is still clinical equipoise surrounding this. TCD may be a tool to gain early information in the setting of TBI much in the same way that point of care ultrasound has found a role in general trauma.

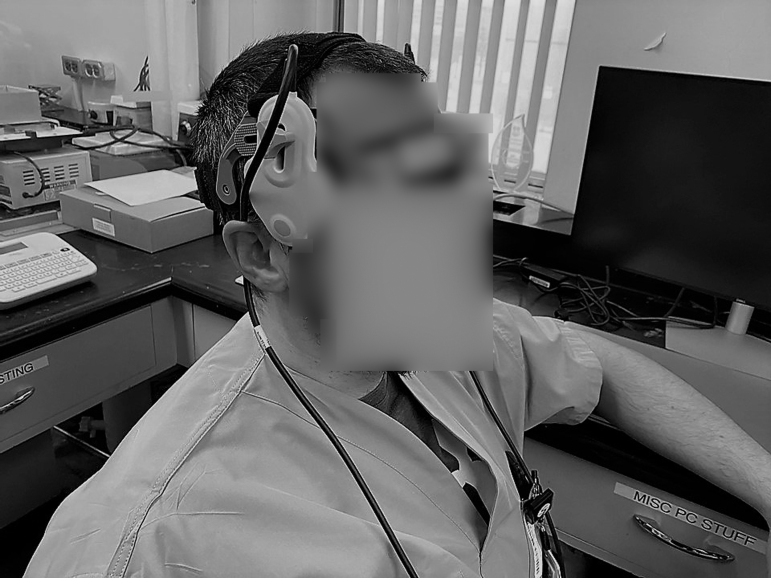

In the acute setting, monitoring of CA is proving to be of greater value. While intermittent methods of measuring CA have their limitations in the acutely ill patients, less invasive methods are gaining traction. On such application of the cerebrovascular reactivity monitoring is the identification of an optimal CPP derived from PRx values, which have been described and are now entering phase II clinical trials.87 Similarly, optimal CPP ranges may be derived from Mx or Sx and in the future may also provide personalized CPP targeted therapy.88 As can be seen in Figure 4, by plotting Mx or PRx versus CPP a parabolic relationship can be observed. The nadir of this curve is the CPP at which cerebrovascular reactivity is most intact and therefore represents an optimal CPP.88 One of the major limitations to this has been the semi-intermittent nature of TCD recordings. Advances in robotics, however, may provide a solution. Robotic TCD probes are now commercially available. They utilize complex algorithms to periodically adjust the TCD probe to significantly extend the length of recordings. An example of one such robotic probe can be seen in Figure 5. These have been shown to provide sufficient quality recordings to potentially convert these TCD based indices of CA in a continuous method.89,90

FIG. 4.

An example of continuous arterial blood pressure (ABP), intracranial pressure (ICP), and flow velocity (FV) data for a single patient. Also presented are the associated pressure reactivity (PRx) and mean flow velocity index (Mx) versus cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) graphs that demonstrate a parabolic relationship. A concordant optimal CPP, where cerebrovascular reactivity is most intact, can be identified at approximately 61.25 mm Hg. Modified from an open access 2018 article by Zeiler and colleagues and used with permission from the corresponding author.88

FIG. 5.

Robotic transcranial Doppler (TCD) setup using a Delica EMS 9D robotic TCD device (Delica EMS 9D System, Shenzen Delica Medical Equipment Co. Ltd, China).

Assessment of CA and other physiologic metrics in TBI patients in the long-term has been limited by their invasive nature. TCD provides a non-invasive means by which to evaluate these patients. The long-term implication of TBI on CA should be more fully explored across the entire recovery period post-TBI, and non-invasive indices of CA such as Mx_a and Sx_a may allow for that. 70 This work is in the preliminary phase but may help expand the physiologic management of TBI beyond the acute setting.89,90

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the artistic contribution of Jon Stepaniuk with regards to the creation of Figure 1.

Authors' Contributions

AG was responsible for reviewing the body of original literature, preparation of the manuscript and creation of the tables and figures. CB, LF and AS were responsible for editing for the manuscript. FAZ was responsible for structuring and editing of the manuscript.

Funding Information

AG is supported through the University of Manitoba Clinician Investigator Program.

CB is supported through the Centre on Aging Fellowship at the University of Manitoba.

LF is supported through the University of Manitoba - Department of Surgery GFT Research Grant, and the University of Manitoba Office of Research Services (ORS) – University Research Grant Program (URGP).

FAZ receives research support from the Manitoba Public Insurance (MPI) Neuroscience/TBI Research Endowment, the Health Sciences Centre Foundation Winnipeg, the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)(Grant #: R03NS114335-01), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)(Grant #: 432061), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI)(Project #: 38583), Research Manitoba (Grant #: 3906), the University of Manitoba VPRI Research Investment Fund (RIF), the University of Manitoba Centre on Aging, and the University of Manitoba Rudy Falk Clinician-Scientist Professorship.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Maas, A.I.R., Stocchetti, N., and Bullock, R. (2008). Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 7, 728–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carney, N., Totten, A.M., O'Reilly, C., Ullman, J.S., Hawryluk, G.W.J., Bell, M.J., Bratton, S.L., Chesnut, R., Harris, O.A., Kissoon, N., Rubiano, A.M., Shutter, L., Tasker, R.C., Vavilala, M.S., Wilberger, J., Wright, D.W., and Ghajar, J. (2017). Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 80, 6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Roux, P., Menon, D.K., Citerio, G., Vespa, P., Bader, M.K., Brophy, G.M., Diringer, M.N., Stocchetti, N., Videtta, W., Armonda, R., Badjatia, N., Böesel, J., Chesnut, R., Chou, S., Claassen, J., Czosnyka, M., De Georgia, M., Figaji, A., Fugate, J., Helbok, R., Horowitz, D., Hutchinson, P., Kumar, M., McNett, M., Miller, C., Naidech, A., Oddo, M., Olson, D., O'Phelan, K., Provencio, J.J., Puppo, C., Riker, R., Robertson, C., Schmidt, M., and Taccone, F. (2014). Consensus summary statement of the International Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Neurocrit. Care 21 Suppl 2, S1–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeiler, F.A., Ercole, A., Czosnyka, M., Smielewski, P., Hawryluk, G., Hutchinson, P.J.A., Menon, D.K., and Aries, M. (2020). Continuous cerebrovascular reactivity monitoring in moderate/severe traumatic brain injury: a narrative review of advances in neurocritical care. Br. J. Anaesth. S0007-0912, 30966-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wijayatilake, D.S., Talati, C., and Panchatsharam, S. (2015). The monitoring and management of severe traumatic brain injury in the United Kingdom: is there a consensus? A national survey. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 27, 241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roldan, M., Abay, T.Y., and Kyriacou, P.A. (2020). Non-invasive techniques for multimodal monitoring in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurotrauma [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White, H. and Venkatesh, B. (2006). Applications of transcranial Doppler in the ICU: a review. Intensive Care Med. 32, 981–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reid, J.M. and Spencer, M.P. (1972). Ultrasonic Doppler technique for imaging blood vessels. Science 176, 1235–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aaslid, R., Markwalder, T.M., and Nornes, H. (1982). Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J. Neurosurg. 57, 769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aaslid, R., Huber, P., and Nornes, H. (1984). Evaluation of cerebrovascular spasm with transcranial Doppler ultrasound. J. Neurosurg. 60, 37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giller, C.A., Bowman, G., Dyer, H., Mootz, L., and Krippner, W. (1993). Cerebral arterial diameters during changes in blood pressure and carbon dioxide during craniotomy. Neurosurgery 32, 737–741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Itoh, T., Matsumoto, M., Handa, N., Maeda, H., Hougaku, H., Hashimoto, H., Etani, H., Tsukamoto, Y., and Kamada, T. (1993). Rate of successful recording of blood flow signals in the middle cerebral artery using transcranial Doppler sonography. Stroke 24, 1192–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gosling, R.G. and King, D.H. (1974). Arterial assessment by Doppler-shift ultrasound. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 67, 447–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan, K.H., Miller, J.D., and Dearden, N.M. (1992). Intracranial blood flow velocity after head injury: relationship to severity of injury, time, neurological status and outcome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 787–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Santbrink, H., Schouten, J.W., Steyerberg, E.W., Avezaat, C.J.J., and Maas, A.I.R. (2002). Serial transcranial Doppler measurements in traumatic brain injury with special focus on the early posttraumatic period. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 144, 1141–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sokoloff, C., Williamson, D., Serri, K., Albert, M., Odier, C., Charbonney, E., andBernard, F.; ÉRESI Reseach Group (Équipe de Recherche En Soins Intensifs). (2020). Clinical Usefulness of transcranial Doppler as a screening tool for early cerebral hypoxic episodes in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit. Care 32, 486–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zurynski, Y.A., Dorsch, N.W.C., and Fearnside, M.R. (1995). Incidence and effects of increased cerebral blood flow velocity after severe head injury: a transcranial Doppler ultrasound study II. Effect of vasospasm and hyperemia on outcome. J. Neurol. Sci. 134, 41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trofimov, A., Kopylov, A., Dobrzeniecki, M., Sheludyakov, A., Martynov, D., Trofimova, K., Agarkova, D.I., and Bragin, D.E. (2020). Comparative analysis of simultaneous transcranial Doppler and perfusion computed tomography for cerebral perfusion evaluation in patients with traumatic brain injury. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1232, 55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Czosnyka, M., Smielewski, P., Kirkpatrick, P., Menon, D.K., and Pickard, J.D. (1996). Monitoring of cerebral autoregulation in head-injured patients. Stroke 27, 1829–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan, K.H., Miller, J.D., Dearden, N.M., Andrews, P.J., and Midgley, S. (1992). The effect of changes in cerebral perfusion pressure upon middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity and jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation after severe brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 77, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moreno, J.A., Mesalles, E., Gener, J., Tomasa, A., Ley, A., Roca, J., and Fernández-Llamazares, J. (2000). Evaluating the outcome of severe head injury with transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. Neurosurg. Focus 8, e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ziegler, D., Cravens, G., Poche, G., Gandhi, R., and Tellez, M. (2017). Use of transcranial Doppler in patients with severe traumatic brain injuries. J. Neurotrauma 34, 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fatima, N., Shuaib, A., Chughtai, T.S., Ayyad, A., and Saqqur, M. (2019). The role of transcranial Doppler in traumatic brain injury: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Neurosurg. 14, 626–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaffres, P., Brun, J., Declety, P., Bosson, J.L., Fauvage, B., Schleiermacher, A., Kaddour, A., Anglade, D., Jacquot, C., and Payen, J.F. (2005). Transcranial Doppler to detect on admission patients at risk for neurological deterioration following mild and moderate brain trauma. Intensive Care Med. 31, 785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bouzat, P., Francony, G., Declety, P., Genty, C., Kaddour, A., Bessou, P., Brun, J., Jacquot, C., Chabardes, S., Bosson, J.-L., and Payen, J.-F. (2011). Transcranial Doppler to screen on admission patients with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery 68, 1603–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bouzat, P., Almeras, L., Manhes, P., Sanders, L., Levrat, A., David, J.S., Cinotti, R., Chabanne, R., Gloaguen, A., Bobbia, X., Thoret, S., Oujamaa, L., Bosson, J.L., Payen, J.F., Asehnoune, K., Pes, P., Lefrant, J.Y., Mirek, S., Albasini, F., Scrimgeour, C., Thouret, J.M., Chartier, F., and Ginet, M.; TBI-TCD Study Investigators. (2016). Transcranial Doppler to predict neurologic outcome after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. Anesthesiology 125, 346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang, T., Li, L., Yang, Y., Li, M., Qu, Y., and Gao, L. (2019). Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography for the management of severe traumatic brain injury after decompressive craniectomy. World Neurosurg. 126, e116–e124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perrein, A., Petry, L., Reis, A., Baumann, A., Mertes, P., and Audibert, G. (2015). Cerebral vasospasm after traumatic brain injury: an update. Minerva Anestesiol. 81, 1219–1228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Compton, J.S., and Teddy, P.J. (1987). Cerebral arterial vasospasm following severe head injury: A transcranial Doppler study. Br. J. Neurosurg. 1, 435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin, N.A., Doberstein, C., Zane, C., Caron, M.J., Thomas, K., and Becker, D.P. (1992). Posttraumatic cerebral arterial spasm: transcranial Doppler ultrasound, cerebral blood flow, and angiographic findings. J. Neurosurg. 77, 575–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steiger, H.J., Aaslid, R., Stooss, R., and Seiler, R.W. (1994). Transcranial Doppler monitoring in head injury: relations between type of injury, flow velocities, vasoreactivity, and outcome. Neurosurgery 34, 79–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lindegaard, K.F., Nornes, H., Bakke, S.J., Sorteberg, W., and Nakstad, P. (1988). Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage investigated by means of transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. (Wien) 42, 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weber, M., Grolimund, P., and Seiler, R.W. (1990). Evaluation of posttraumatic cerebral blood flow velocities by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. Neurosurgery 27, 106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aaslid, R. (1986). The Doppler principle applied to measurement of blood flow velocity in cerebral arteries, in: Transcranial Doppler Sonography. R. Aaslid, (ed). Springer Vienna: Vienna, Austria, pps. 22–38 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goraj, B., Rifkinson-Mann, S., Leslie, D.R., Lansen, T.A., Kasoff, S.S., and Tenner, M.S. (1994). Correlation of intracranial pressure and transcranial Doppler resistive index after head trauma. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 15, 1333–1339 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morgalla, M.H. and Magunia, H. (2016). Noninvasive measurement of intracranial pressure via the pulsatility index on transcranial Doppler sonography: is improvement possible? J. Clin. Ultrasound JCU 44, 40–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kashif, F.M., Verghese, G.C., Novak, V., Czosnyka, M., and Heldt, T. (2012). Model-based noninvasive estimation of intracranial pressure from cerebral blood flow velocity and arterial pressure. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 129ra44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidt, B., Czosnyka, M., Smielewski, P., Plontke, R., Schwarze, J.J., Klingelhöfer, J., and Pickard, J.D. (2016). Noninvasive assessment of ICP: evaluation of new TBI data. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 122, 69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cardim, D., Robba, C., Donnelly, J., Bohdanowicz, M., Schmidt, B., Damian, M., Varsos, G.V., Liu, X., Cabeleira, M., Frigieri, G., Cabella, B., Smielewski, P., Mascarenhas, S., and Czosnyka, M. (2016). Prospective study on noninvasive assessment of intracranial pressure in traumatic brain-injured patients: comparison of four methods. J. Neurotrauma 33, 792–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cardim, D., Schmidt, B., Robba, C., Donnelly, J., Puppo, C., Czosnyka, M., and Smielewski, P. (2017). Transcranial Doppler monitoring of intracranial pressure plateau waves. Neurocrit. Care 26, 330–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Czosnyka, M., Smielewski, P., Piechnik, S., Al-Rawi, P.G., Kirkpatrick, P.J., Matta, B.F., and Pickard, J.D. (1999). Critical closing pressure in cerebrovascular circulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 66, 606–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weyland, A., Buhre, W., Grund, S., Ludwig, H., Kazmaier, S., Weyland, W., and Sonntag, H. (2000). Cerebrovascular tone rather than intracranial pressure determines the effective downstream pressure of the cerebral circulation in the absence of intracranial hypertension. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 12, 210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zweifel, C., Czosnyka, M., Carrera, E., de Riva, N., Pickard, J.D., and Smielewski, P. (2012). Reliability of the blood flow velocity pulsatility index for assessment of intracranial and cerebral perfusion pressures in head-injured patients. Neurosurgery 71, 853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Czosnyka, M., Matta, B.F., Smielewski, P., Kirkpatrick, P.J., and Pickard, J.D. (1998). Cerebral perfusion pressure in head-injured patients: a noninvasive assessment using transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. J. Neurosurg. 88, 802–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schmidt, E.A., Czosnyka, M., Gooskens, I., Piechnik, S.K., Matta, B.F., Whitfield, P.C., and Pickard, J.D. (2001). Preliminary experience of the estimation of cerebral perfusion pressure using transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 70, 198–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Varsos, G.V., Werndle, M.C., Czosnyka, Z.H., Smielewski, P., Kolias, A.G., Phang, I., Saadoun, S., Bell, B.A., Zoumprouli, A., Papadopoulos, M.C., and Czosnyka, M. (2015). Intraspinal pressure and spinal cord perfusion pressure after spinal cord injury: an observational study. J. Neurosurg. Spine 23, 763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tazarourte, K., Atchabahian, A., Tourtier, J.P., David, J.S., Ract, C., Savary, D., Monchi, M., and Vigué, B. (2011). Pre-hospital transcranial Doppler in severe traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 55, 422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fog, M. (1938). The relationship between the blood pressure and the tonic regulation of the pial arteries. J. Neurol. Psychiatry 1, 187–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lassen, N.A. (1959). Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol. Rev. 39, 183–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Overgaard, J. and Tweed, W.A. (1974). Cerebral circulation after head injury: part 1: cerebral blood flow and its regulation after closed head injury with emphasis on clinical correlations. J. Neurosurg. 41, 531–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cold, G.E. and Jensen, F.T. (1978). Cerebral autoregulation in unconscious patients with brain injury. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 22, 270–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aaslid, R., Lindegaard, K.F., Sorteberg, W., and Nornes, H. (1989). Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke 20, 45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tiecks, F.P., Lam, A.M., Aaslid, R., and Newell, D.W. (1995). Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurements. Stroke 26, 1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hlatky, R., Furuya, Y., Valadka, A.B., Gonzalez, J., Chacko, A., Mizutani, Y., Contant, C.F., and Robertson, C.S. (2002). Dynamic autoregulatory response after severe head injury. J. Neurosurg. 97, 1054–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schramm, P., Klein, K.U., Pape, M., Berres, M., Werner, C., Kochs, E., and Engelhard, K. (2011). Serial measurement of static and dynamic cerebrovascular autoregulation after brain injury. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 23, 41–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sviri, G.E., Aaslid, R., Douville, C.M., Moore, A., and Newell, D.W. (2009). Time course for autoregulation recovery following severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 111, 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hlatky, R., Valadka, A.B., and Robertson, C.S. (2006). Analysis of dynamic autoregulation assessed by the cuff deflation method. Neurocrit. Care 4, 127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Giller, C.A. (1991). A bedside test for cerebral autoregulation using transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 108, 7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Smielewski, P., Czosnyka, M., Kirkpatrick, P., McEroy, H., Rutkowska, H., and Pickard, J.D. (1996). Assessment of cerebral autoregulation using carotid artery compression. Stroke 27, 2197–2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]