Abstract

Objective:

To compare discharge opioid refills, prescribed morphine equivalent dose and quantity, and longitudinal patient-reported outcomes before and after implementation of a tiered opioid prescribing algorithm among women undergoing open gynecologic surgery within an enhanced recovery after surgery program.

Methods:

We compared opioid prescriptions, clinical outcomes, and patient-reported outcomes among 273 women. Post-discharge symptom burden was collected up to 42 days after discharge using the validated 27-item MD Anderson Symptom Inventory and analyzed using linear mixed effects models and Kaplan-Meier curves for symptom recovery.

Results:

Among 113 pre-implementation and 160 post-implementation patients, there was no difference in opioid refills (9.7% vs 11.3%, p=.84). The post-implementation cohort had a significant reduction in median morphine equivalent dose (112.5mg vs 225mg, p<.01) with no difference in median hospital length of stay (3 days vs 3 days, p=1.0) or 30-day readmission rate (9.5% vs 7.1%, p=.66). There was no difference in patient-reported pain between the pre- and post-implementation cohorts on the day of discharge (severity 4.93 vs 5.14, p=.53) or in any patient-reported symptoms, interference measures, or composite scores by post-discharge day 7. The median recovery time for most symptoms was 7 days, except for pain (14 days), fatigue (18 days), and physical interference (21 days), with no differences between cohorts.

Conclusions:

After implementation of a tiered opioid prescribing algorithm, the quantity and dose of discharge opioids prescribed decreased with no change in postoperative refills and without negatively impacting patient-reported symptom burden or interference, which can be used to educate and reassure patients and providers.

INTRODUCTION

The United States is in the midst of an opioid epidemic which has had significant individual and public health consequences and continues to accelerate despite increasing awareness of the problem [1–3]. Prescription opioids contribute significantly to opioid overdose deaths, which rose to nearly 50,000 in 2019 and accelerated further during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 [2, 3]. A large driver of the opioid epidemic is physician over-prescription of opioids [4, 5]. The prescription of opioids during the postoperative period has been specifically associated with new and persistent opioid use [6–8], with rates of new persistent opioid use as high as 6.7% after abdominal hysterectomy [8] and 10.4% after curative-intent cancer surgery [9].

In recognition of opioid over-prescription and variation in prescribing patterns across surgical specialties [10–12], guidelines on appropriate postoperative opioid prescribing are increasingly common [13]. Enhanced recovery after surgery pathways, which utilize evidence-based perioperative guidelines to improve pain control through multimodal analgesia [14, 15] have been leveraged to decrease postoperative opioid use. Enhanced recovery after surgery pathways have been successful in decreasing postoperative opioid use across surgical specialties [16, 17], including after major open [18] and minimally-invasive [19, 20] gynecologic surgeries.

Although previous studies have demonstrated that restrictive opioid prescribing after surgery does not negatively impact short-term postoperative pain, opioid refills, or complications [21–25], the effects of restrictive opioid prescribing on other patient-reported outcomes are largely unknown. As there are multiple factors besides pain that may be important to patients, an understanding of the longitudinal impacts of restrictive opioid prescribing on both pain and expanded patient-reported outcomes is important to set realistic postoperative expectations for patients.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of a tiered discharge opioid prescribing quality improvement algorithm on the number of opioid refills prescribed to patients undergoing open gynecologic surgery pre- and post-implementation within an enhanced recovery after surgery program. We secondarily sought to compare the morphine equivalent dose, opioid quantity prescribed, and the impact on longitudinal post-discharge patient-reported symptom burden and functional interference between pre- and post-implementation cohorts.

METHODS

Our department implemented a quality improvement initiative using a tiered opioid algorithm beginning on July 1, 2018 to tailor discharge opioid prescriptions. The analysis of data related to this quality improvement project was approved by the institutional review board (protocol PA19–0783). All patient-reported outcomes for this study were collected under separate institutional review board approved protocols (BS99–094, 2017–0412, and 2018–0143). Written, informed consent for patient-reported outcome collection and study participation was obtained from all subjects.

We prospectively examined clinical outcomes, opioid prescriptions, and patient-reported outcomes on all eligible patients who underwent open gynecologic surgery in our enhanced recovery after surgery pathway [18] after implementation of the tiered opioid algorithm from August 1, 2018 to July 31, 2019. To compare outcomes, we used a historical cohort of patients who underwent open gynecologic surgery in our enhanced recovery after surgery pathway between July 1, 2017 and June 30, 2018. Both benign and malignant indications were included. Only patients who provided written, informed consent and completed the baseline preoperative MD Anderson Symptom Inventory and at least two subsequent assessments were included [Supplementary Table 1]. Patients were excluded if they had incomplete medical records, had pre-existing chronic opioid use (defined as long-acting opioid use at the time of pre-operative visit) due to different perioperative pain management considerations for these individuals [14, 26], underwent minimally invasive or emergency surgery, or were consented for separate institutional surgical studies collecting patient-reported outcome data within our enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Patients were not excluded if they had intraoperative or postoperative complications.

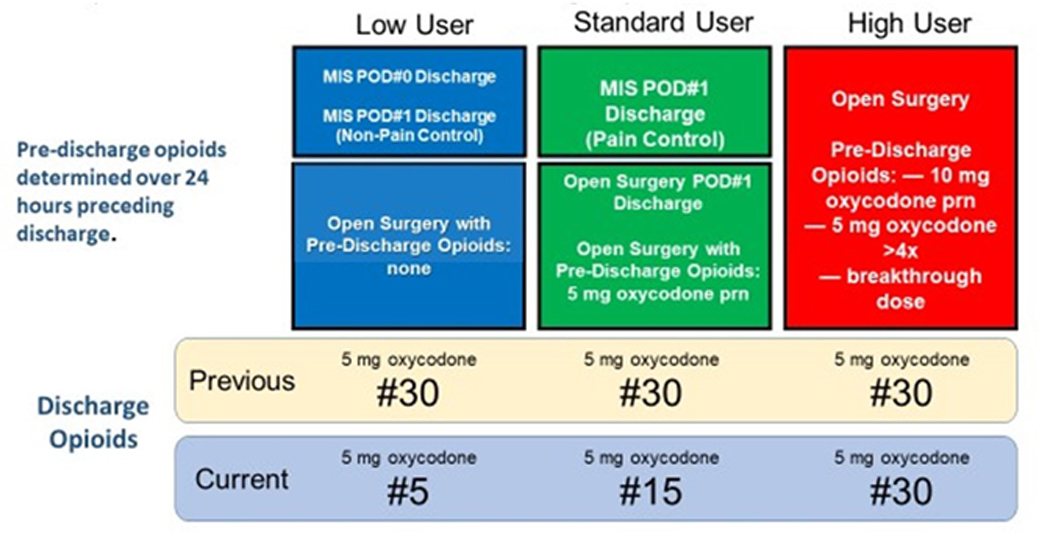

At our institution all patients undergoing open gynecologic surgery within the enhanced recovery after surgery pathway routinely receive preoperative celecoxib, pregabalin, acetaminophen, and tramadol; intraoperative bupivacaine infiltration; and postoperative acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and oxycodone as needed unless contraindicated. At discharge, patients routinely receive prescriptions for ibuprofen and acetaminophen. Prior to this quality improvement initiative, most patients were prescribed thirty 5mg oxycodone tablets at discharge. Based on a prior institutional retrospective cohort study of opioid use after open gynecologic surgery [27], our discharge algorithm was designed so that patients undergoing open surgery received tiered numbers of 5mg oxycodone tablets at discharge depending on their opioid use within the prior 24 hours. Patients who did not use opioids received five oxycodone (5mg) tablets; patients who used 5mg oxycodone as needed or were discharged on postoperative day #1 received 15 oxycodone (5mg) tablets; and patients using 10 mg oxycodone as needed or more than 4 doses of 5 mg oxycodone received 30 oxycodone (5mg) tablets [Figure 1].

Figure 1:

Tiered discharge opioid prescription quality improvement initiative algorithm

• Diagram of tiered opioid algorithm including how discharge opioid prescriptions were determined based on opioid use during the 24 hours prior to discharge and comparison to pre-implementation prescribing.

• Abbreviations: MIS = minimally invasive surgery; POD = post-operative day; mg = milligrams

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture tools [28] hosted at MD Anderson as part of an institutionally approved quality improvement study (protocol QI-6033). Trained and certified research staff abstracted opioid prescription information and clinical outcomes from medical record review. American Society of Anesthesiologists classification and Charlson Comorbidity Index [29] were used to assess comorbidities. Current malignancy was not included in the Charlson Comorbidity Index to more accurately reflect non-cancer comorbidities. To examine algorithm compliance, the number of oxycodone tablets prescribed at discharge was compared to patient opioid use within 24 hours prior to discharge and the proportion of patients who received the correct per protocol number of oxycodone was calculated, excluding patients with incomplete data or who received prescriptions other than 5, 15, or 30 tablets of 5mg oxycodone at discharge. Opioid refills from pharmacy records and readmission rates were recorded for 30 days after discharge.

Perioperative patient-reported symptom burden was evaluated with the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-GYN module, a 27-item validated tool [30], in patients who consented for protocol BS99–094 and had surgery from July 1 2017 to June 30 2018; and with the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory-PeriOP-GYN module, a recently validated tool for patients undergoing gynecologic surgery [31], in patients who consented for protocol 2018–0143, 2017–0412, or BS99–0942 with surgery after July 1, 2018. Identical patient-reported outcome items in the two instruments were utilized. For each instrument component, individuals were asked to rank symptom severity during the previous 24 hours on a scale of 0–10, with 0 being “not present” and 10 being “as bad as you can imagine.” Symptom interference was also assessed on a 0–10 scale, with 0 being “did not interfere” and 10 being “interfered completely.” The total interference score was a composite endpoint of 6 interference questions that asked patients to report how much their symptoms interfered with affective (relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood) and physical (walking, general activity, and work) components. Both instruments were administered by trained study staff at the time of preoperative visit, daily while admitted postoperatively, on days 3 and 7 after hospital discharge, and weekly for six weeks after discharge.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze clinical and demographic characteristics of study cohorts. Categorical variables were compared between cohorts with Fisher exact tests or chi squared tests. Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing curves were fitted to 42 days after hospital discharge and generalized linear mixed effects modeling with random intercept was used to examine the longitudinal change of symptom burden after hospital discharge up to 14 days for pain and up to 7 days for all other variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to illustrate the time to return to mild or no symptom burden, defined as a score <4 at two consecutive assessments. The log-rank test was used to compare the two cohorts with respect to the median time to return to mild or no symptom burden. The linear mixed effects models and time to event analyses were adjusted for hospital length of stay.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2 (2020–06-22) R 3.5.1 for Mac OS X.22 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All P-values reported are 2-tailed, with statistical significance level of α=0.05. The Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines [32] were used in the planning of the quality improvement initiative and the preparation of this manuscript. In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, we will provide our data for the reproducibility of this study in other centers if such is requested.

RESULTS

A total of 570 patients underwent open gynecologic surgery within our enhanced recovery after surgery pathway following implementation of the tiered opioid algorithm quality improvement initiative. Of these, 164 patients provided consent for patient-reported outcomes collection and 160 were included in analysis; the pre-implementation comparison cohort was drawn from 246 patients who underwent open gynecologic surgery prior to the start of the quality improvement initiative, of which 117 provided consent for longitudinal patient-reported outcomes collection and 113 were included in analysis [ Supplementary Figure 1]. Clinical and demographic variables in the pre- and post-implementation cohorts are provided in Table 1, with no significant differences between cohorts.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical variables by opioid prescribing cohort

| Demographic / clinical variable | Pre-implementation (n=113) | Post-implementation (n=160) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 59 (26–84) | 57 (19–83) | .07 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), n (%) | .80 | ||

| Less than 25 | 32 (28.3) | 51 (31.9) | |

| 25–39.9 | 65 (57.5) | 86 (53.8) | |

| 40 or greater | 16 (14.2) | 23 (14.4) | |

| Ethnicity*, n (%)† | .09 | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latina | 91 (80.5) | 131 (81.9) | |

| Hispanic or Latina | 21 (18.6) | 26 (16.3) | |

| Not reported | 1 (.9) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Race*, n (%)† | .41 | ||

| White | 75 (66.4) | 113 (70.6) | |

| Black | 18 (15.9) | 18 (11.3) | |

| Asian | 5 (4.4) | 12 (7.5) | |

| Other | 15 (13.3) | 16 (.1) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 1 (.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%)† | .54 | ||

| Single | 22 (19.5) | 27 (16.9) | |

| Married or Significant Other | 70 (61.9) | 99 (61.9) | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 19 (16.8) | 33 (20.6) | |

| Other | 1 (.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Not reported | 1 (.9) | 1 (.6) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | .23 | ||

| Never smoker | 83 (73.5) | 104 (.65) | |

| Former smoker | 24 21.2) | 40 (25) | |

| Current smoker | 6 (5.3) | 16 (.1) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | .64 | ||

| 0 | 31 (27.4) | 44 (27.5) | |

| 1–2 | 55 (48.7) | 85 (53.1) | |

| 3 or greater | 27 (23.9) | 31 (19.4) | |

| ASA, n (%) | .30 | ||

| I-II | 12 (10.6) | 10 (6.3) | |

| III-IV | 101 (89.4) | 148 (92.5) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Hysterectomy performed, n (%) | 92 (81.4) | 136 (85) | .51 |

| Surgical indication, n (%)‡ | .13 | ||

| Benign | 27 (23.5) | 40 (24.5) | |

| Cervical cancer | 5 (4.3) | 21 (12.9) | |

| Ovarian, fallopian tube, primary peritoneal cancer | 52 (45.2) | 71 (43.6) | |

| Uterine cancer (non-sarcoma) | 17 (14.8) | 20 (12.3) | |

| Uterine sarcoma | 3 (2.6) | 1 (.6) | |

| Other | 11 (9.6) | 10 (6.1) |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Ethnicity and race as reported by the patient. For analysis purposes, the “Other” race category includes Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and Other not specified

Statistical tests were performed after excluding “Not reported” category.

Patients may have had more than one indication for surgery.

Outcomes measures by cohort are shown in Table 2. The pre- and post-implementation cohorts had no difference in the proportion of patients requiring opioid refills up to 30 days post-discharge (9.7% vs 11.3%, p=.84). Compared to the pre-implementation cohort, the tiered opioid cohort had a significantly lower discharge morphine equivalent dose (112.5mg vs 225 mg, p<.001) and significantly fewer patients received 30 oxycodone tablets at discharge (26.9% vs 77%, p<.001). There was no difference between cohorts in median length of stay (3 days vs 3 days, p=1.0) or 30-day readmission rate (9.4% vs 7.1%, p=.66). Of patients in the tiered opioid cohort only, patients receiving 30 tablets of oxycodone had a significantly higher rate of refills compared to patients receiving 5 or 15 tablets (6.3% vs 2.5% vs 1.9%, p=.036), with no difference in 30-day readmission rates (2.5% vs 4.4% vs 1.3%, p=.61).

Table 2:

Clinical outcomes and opioid prescription patterns by opioid prescribing cohort

| Outcome variable | Pre-implementation (n=113) | Post-implementation (n=160) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median MED at discharge, mg (range) | 225 (75–450) | 112.5 (9–675) | <.001 |

| Discharge opioid prescription, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| 5 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | 0 (0) | 43 (26.9) | |

| 15 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | 1 (.9) | 56 (35) | |

| 30 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | 87 (77) | 43 (26.9) | |

| Other | 25 (22.1) | 18 (11.3) | |

| Opioid refill provided, n (%) | 11 (9.7) | 18 (11.3) | .84 |

| Refills by # opioids prescribed, n (%)* | .036 | ||

| 5 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | - | 3 (1.9) | |

| 15 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | - | 4 (2.5) | |

| 30 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | - | 10 (6.3) | |

| Other | - | 1 (.6) | |

| Median length of stay, days (range) | 3 (1–10) | 3 (1–10) | 1.0 |

| Readmission, n(%) | 8 (7.1) | 15 (9.4) | .66 |

| Readmission by # opioids prescribed, n (%)* | .61 | ||

| 5 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | - | 2 (1.3) | |

| 15 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | - | 7 (4.4) | |

| 30 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone | - | 4 (2.5) | |

| Other | - | 2 (1.3) |

Significant p-values signified in bold text

MED, morphine equivalent dose

Comparison between groups receiving 5, 10, and 15 tablets of oxycodone at discharge among prospective post-implementation cohort only

Within the tiered opioid algorithm cohort, 55.7% of patients received the correct number of oxycodone tablets at discharge based on the algorithm. When examined by number of tablets prescribed, 43.6% of patients discharged with 5 tablets, 52.2% of patients discharged with 15 tablets, and 74.2% of patients discharged with 30 tablets received the correct number. By number of oxycodone tablets prescribed at discharge, 25.8% of patients who received 30 tabs of oxycodone received too many and 23% of patients who received 15 tabs of oxycodone received too many per the algorithm. In comparison, 56.4% of patients who received 5 tabs of oxycodone received too few and 77% of patients who received 15 tabs of oxycodone received too few per the algorithm.

Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing curves were fitted to illustrate longitudinal change in patient-reported symptom severity and interference out to 42 days after hospital discharge for both pre- and post-implementation cohorts [Figure 2]. In Kaplan-Meier models, the median time for patient-reported recovery to mild or no symptom burden was 7 days for lack of appetite, abdominal bloating, drowsiness, constipation, and affective interference; 14 days for pain; 18 days for fatigue; and 21 days for physical interference, with no statistically significant differences between pre- and post-implementation prescribing cohorts in median recovery time for these variables.

Figure 2:

Longitudinal patient-reported symptoms and interference by opioid prescribing cohort

• Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing curves illustrating mean longitudinal patient-reported (A) pain, (B) constipation, (C) fatigue, (D) nausea, (E) sleep disturbance, (F) difficulty urinating, (G) abdominal bloating, (H) affective interference [REM = relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood], and (I) physical interference [WAW=walking, general activity, and work] out to 42 days post-discharge for pre-implementation (blue) and post-implementation (red) cohorts. Shading represents 95% confidence interval.

• Abbreviations: REM = relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood; WAW=walking, general activity, and work

On the day of hospital discharge, there was no difference in pain between the pre- and post-implementation cohorts (4.93 vs 5.14, p=.53). Of the remaining MD Anderson Symptom Inventory measures on the day of discharge, the only differences in symptom burden were higher abdominal bloating (3.14 vs 4.32; p=.034) and difficulty urinating (.83 vs .51; p=.045) scores in the tiered opioid cohort compared to the pre-implementation cohort; however, by post-discharge day 7 there were no significant differences between pre- and post-implementation cohorts in any patient-reported symptoms or interference measures [Table 3].

Table 3:

Selected MDASI responses by opioid prescribing cohort on date of discharge and at post-discharge day 7

| MDASI symptom measure | Date of discharge | Post-hospital discharge day 7 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-implementation | Post-implementation | P-value | Pre-implementation | Post-implementation | P-value | |||||

| N | Mean ±SD | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | |||

| Pain | 91 | 4.93 ± 2.6 | 155 | 5.14 ± 2.54 | .53 | 88 | 3.18 ± 2.65 | 139 | 3.24 ± 2.26 | .44 |

| Fatigue | 91 | 4.22 ± 2.82 | 155 | 4.31 ± 2.76 | .98 | 88 | 3.24 ± 2.47 | 139 | 3.24 ± 2.25 | .77 |

| Nausea | 91 | 1.57 ± 2.71 | 155 | 1.21 ± 2.02 | .94 | 88 | .81 ± 2.04 | 138 | .34 ± .91 | .59 |

| Disturbed sleep | 91 | 3.26 ± 3.44 | 155 | 3.7 ± 3.11 | .19 | 88 | 2.31 ± 2.48 | 139 | 2.65 ± 2.44 | .19 |

| Drowsiness | 91 | 3.44 ± 3.04 | 155 | 3.57 ± 2.8 | .59 | 87 | 1.55 ± 1.94 | 139 | 1.54 ± 1.74 | .85 |

| Lack of appetite | 91 | 3.03 ± 3.03 | 155 | 3.19 ± 3.05 | .71 | 88 | 1.8 ± 2.06 | 139 | 1.45 ± 1.99 | .12 |

| Distress | 91 | 1.66 ± 2.63 | 155 | 1.6 ± 2.38 | .61 | 88 | 1.74 ± 2.47 | 138 | 1.35 ± 1.88 | .62 |

| Constipation | 87 | 2.59 ± 3.25 | 153 | 3.4 ± 3.88 | .26 | 86 | 1.48 ± 2.47 | 137 | 1.24 ± 2.16 | .37 |

| Abdominal bloating | 37 | 3.14 ± 2.81 | 155 | 4.32 ± 2.99 | .034 | 32 | 1.84 ± 1.9 | 139 | 2.46 ± 2.18 | .13 |

| Difficulty urinating | 36 | .14 ± .83 | 153 | .51 ± 1.59 | .045 | 32 | .25 ± .8 | 138 | .49 ± 1.48 | .48 |

| Walking | 91 | 3.19 ± 2.99 | 155 | 3.43 ± 3.01 | .53 | 87 | 2.59 ± 2.25 | 139 | 2.63 ± 2.58 | .8 |

| REM | 91 | 2.23 ± 2.64 | 155 | 2.37 ± 2.42 | .39 | 87 | 1.93 ± 2.14 | 139 | 1.89 ± 2.06 | 1.0 |

| WAW | 91 | 4.99 ± 2.93 | 155 | 4.92 ± 2.89 | .86 | 87 | 4.04 ± 2.49 | 139 | 3.94 ± 2.69 | .79 |

Significant p-values signified in bold text

MDASI = MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; SD=standard deviation; REM = relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood; WAW=walking, general activity, and work

In the mixed models analysis for fatigue, nausea, sleep disturbance, distress, lack of appetite, drowsiness, difficulty urinating, affective interference, and physical interference, there was a significant time effect but no group effects, indicating that symptom burden decreased over time but did not differ between the pre- and post-implementation cohorts. Mixed effect models showed that abdominal bloating and constipation were significantly higher in the opioid algorithm cohort compared to the pre-implementation cohort up to 7 days post discharge (p=.020 and p=.028, respectively). The change in symptom burden of pain (p=.044) and constipation (p=.029) decreased significantly faster after discharge in the tiered opioid cohort compared to the pre-implementation cohort after controlling for length of stay with no difference in symptom burden between cohorts.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

In our study, a tiered discharge opioid prescribing algorithm significantly decreased the quantity and morphine equivalent dose of discharge opioid prescriptions without compromising longitudinal patient-reported symptoms or interference measures. The symptoms which were worse in the post-implementation cohort at discharge had small absolute differences and may not reflect clinically meaningful differences. Symptoms which were worse in the post-implementation cohort resolved within one week, and both cohorts had median recovery of symptom burden and functional interference by 7–21 days post-discharge. In mixed-models analysis, time, and not prescribing cohort, had the most prominent effect on symptom improvement.

Results in the context of published literature

Our findings are consistent with previous reports that restrictive opioid prescribing decreases the quantity and dose of opioids prescribed without negatively impacting short-term pain, opioid refills, hospital length of stay, or readmissions [21–25]. Our results are similar to studies by Mark et al [23] and Glaser et al [25] which examined postoperative prescriptions in gynecologic enhanced recovery after surgery populations after implementing tiered opioid prescribing guidelines, and builds on this work by examining an expanded set of patient-reported outcomes over multiple time points in patients who exclusively underwent open gynecologic surgery [14, 15].

Our results on longitudinal patient-reported outcomes, which remain underutilized in surgical studies [33], add new information to the gynecologic surgical literature and expands the understanding of non-pain related factors which affect patients’ postoperative course. Other gynecologic studies reporting patient-reported outcomes have examined minimally invasive cohorts [19], surgical route [34, 35] or the effect of enhanced recovery after surgery pathways [18] but have not examined the effect of restrictive opioid prescribing in open gynecologic surgery.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The biggest strength of our study is the inclusion of longitudinal patient-reported outcomes using a validated survey instrument that has been specifically adapted for gynecologic surgery [30, 31]. There was a low drop-off rate over our follow-up period in both cohorts [Supplementary Table 1], confirming the feasibility of collecting longitudinal postoperative patient-reported outcomes [35]. The use of multiple post-discharge follow-up time points in our study provides a more comprehensive perspective than a single timepoint or shorter follow-up periods. We included a broad range of indications, increasing the generalizability of our results. Because our prescribing algorithm is based on a prior institutional study [27], it has high internal validity.

The low overall provider compliance with our quality improvement initiative is our largest limitation. Unfortunately, our study did not record reasons for algorithm non-compliance. However, the fact that patients who received incorrect numbers of oxycodone tablets most often received too few tablets without negatively impacting opioid refills or patient-reported outcomes speaks to the potential to further limit discharge opioid prescribing beyond our current algorithm. While low compliance may have biased our results toward the null, the median morphine equivalent dose prescribed at discharge significantly decreased by 50% after implementation of our algorithm, comparable to similar efforts [36] and in line with our initiative’s goal of decreasing discharge opioid prescriptions.

Other limitations include the single-institution and quality improvement design of the study. We did not separately examine patient-reported outcomes by benign or malignant indication, which may involve different symptom burden. Because we implemented the discharge algorithm within a well-established enhanced recovery after surgery pathway, our results may not be valid for practices which do not already incorporate similar protocols. Our data cannot be extrapolated to minimally invasive surgery. Only patients who provided informed consent for patient-reported outcomes collection were included; patients who did not consent may have had barriers to patient-reported outcome collection or other differences compared to patients who did not consent which may have biased our results. In addition, because we excluded chronic opioid users, our results do not apply to this population of patients, who often require different perioperative pain management including higher postoperative opioid requirements and referral to pain specialist [14, 26].

Implications for Practice and Future Research

Within our post-implementation cohort, patients who received the highest number of tablets at discharge requested the most refills, which may speak to patient differences in pain perception or indicate potentially abusive habits [5–7]; these patients may warrant screening for abuse postoperatively. Future institutional quality improvement cycles could examine compliance over time and refine our algorithm to further restrict or potentially eliminate discharge opioid prescriptions in appropriate patients while maintaining acceptable patient-reported outcomes, especially as the use of opioid-free analgesia gains traction [37]. Our algorithm is now standard-of-care for institutional discharge prescribing after open gynecologic surgery and we have renewed provider education on the algorithm to increase compliance. Our algorithm could be easily adopted by other institutions aiming to decrease discharge opioid prescriptions.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that a tiered opioid prescribing algorithm after open gynecologic surgery safely decreased opioid prescriptions without compromising patient outcomes, which can guide postoperative expectations and assure both patients and surgeons. Incorporation of restrictive postoperative discharge opioid algorithms may be an effective strategy to reduce the morbidity and mortality related to opioid prescribing in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Overview of study cohorts

• CONSORT diagram of patients eligible for, enrolled, and included in the pre-implementation and post-implementation cohorts.

• Abbreviations: ERAS = Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; PRO = patient-reported outcome; MDASI = MD Anderson Symptom Inventory

Supplementary Table 1: Patient-reported outcomes data availability at each analyzed timepoint

HIGHLIGHTS.

A tiered opioid prescribing algorithm decreased the dose and quantity of opioid prescribed at discharge

A tiered opioid prescribing algorithm had no differences in longitudinal patient-reported pain after discharge

A tiered opioid prescribing algorithm had no differences in longitudinal patient-reported functioning

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This work was supported in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH/NCI P30 CA016672, CA217685) and the T32 training grant CA101642 (SPH). LAM is supported by a NIH-NCIK07-CA201013 grant. XSW is supported by NCI/NIH “Improving Recovery After Major Cancer Surgery Using Patient-Reported Outcomes”, R01CA205146.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: LAM reports research funding from AstraZeneca, consulting for Glaxo-Smith-Kline, and stocks in Crispr and Bristol-Myers Squibb. LAW reports grants from AstraZeneca, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, and Eli Lily. GEM reports a research/academic grant from PACIRA Pharmaceutical. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest related to the subject matter of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomes T, et al. , The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open, 2018. 1(2): p. e180217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattson CL, et al. , Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2021. 70(6): p. 202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.: Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guy GP Jr., et al. , Vital Signs: Changes in Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2017. 66(26): p. 697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berterame S, et al. , Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: a worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet, 2016. 387(10028): p. 1644–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brummett CM, et al. , New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg, 2017. 152(6): p. e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii MH, et al. , Post-Discharge Opioid Prescribing and Use after Common Surgical Procedure. J Am Coll Surg, 2018. 226(6): p. 1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright JD, et al. , Use and Misuse of Opioids After Gynecologic Surgical Procedures. Obstet Gynecol, 2019. 134(2): p. 250–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, et al. , New Persistent Opioid Use Among Patients With Cancer After Curative- Intent Surgery. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35(36): p. 4042–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith KC, et al. , Opioid Prescription and Patient Use After Gynecologic Procedures: A Survey of Patients and Providers. J Minim Invasive Gynecol, 2018. 25(4): p. 684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill MV, et al. , Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Ann Surg, 2017. 265(4): p. 709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eid AI, et al. , Variation of Opioid Prescribing Patterns among Patients undergoing Similar Surgery on the Same Acute Care Surgery Service of the Same Institution: Time for Standardization? Surgery, 2018. 164(5): p. 926–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill MV, et al. , Guideline for Discharge Opioid Prescriptions after Inpatient General Surgical Procedures. J Am Coll Surg, 2018. 226(6): p. 996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson G, et al. , Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2019. 29(4): p. 651–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miralpeix E, et al. , A call for new standard of care in perioperative gynecologic oncology practice: Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs. Gynecol Oncol, 2016. 141(2): p. 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gridley C, et al. , Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol for Patients Undergoing Ureteroscopy: Prospective Evaluation of an Opioid-Free Protocol. J Endourol, 2020. 34(6): p. 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulder JK, et al. , Opioid Use in the Postoperative Arena: Global Reduction in Opioids After Surgery Through Enhanced Recovery and Gynecologic Surgery. Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2019. 62(1): p. 67–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer LA, et al. , Effect of an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Program on Opioid Use and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Obstet Gynecol, 2018. 132(2): p. 281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weston E, et al. , Opioid use after minimally invasive hysterectomy in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol> 2019. 155(1): p. 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hillman RT, et al. , Longitudinal patient-reported outcomes and restrictive opioid prescribing after minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pius AK, et al. , Patients’ Experience With Opioid Pain Medication After Discharge From Surgery: A Mixed-Methods Study. J Surg Res, 2020. 256: p. 328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howard R, et al. , Reduction in Opioid Prescribing Through Evidence-Based Prescribing Guidelines. JAMA Surg, 2018. 153(3): p. 285–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mark J, et al. , Ultrarestrictive Opioid Prescription Protocol for Pain Management After Gynecologic and Abdominal Surgery. JAMA Netw Open, 2018. 1(8): p. e185452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson ERW, et al. , A randomized controlled noninferiority trial of reduced vs routine opioid prescription after prolapse repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glaser GE, et al. , Outcomes and patient perspectives following implementation of tiered opioid prescription guidelines in gynecologic surgery. Gynecol Oncol, 2020. 157(2): p. 476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coluzzi F, et al. , The challenge of perioperative pain management in opioid-tolerant patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2017. 13: p. 1163–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillman RT, et al. , Patient characteristics and opioid use prior to discharge after open gynecologic surgery in an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program. Gynecol Oncol, 2019. 153(3): p. 604–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, et al. , Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 2009. 42(2): p. 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson ME, et al. , A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis, 1987. 40(5): p. 373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sailors MH, et al. , Validating the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) for use in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol, 2013. 130(2): p. 323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang XS, et al. , Validation and application of a module of the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory for measuring perioperative symptom burden in patients with gynecologic cancer (theMDASI-PeriOp-GYN). Gynecol Oncol, 2019. 152(3): p. 492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogrinc G, et al. , Squire 2.0 (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. Am J Crit Care, 2015. 24(6): p. 466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiore JF Jr., et al. , How Do We Value Postoperative Recovery?: A Systematic Review of the Measurement Properties of Patient-reported Outcomes After Abdominal Surgery. Ann Surg, 2018. 267(4): p. 656–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kluivers KB, et al. , Comparison of laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy in terms of quality of life: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2008. 136(1): p. 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janda M, et al. , Quality of life after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer (LACE): a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol, 2010. 11(8): p. 772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill MV, et al. , An Educational Intervention Decreases Opioid Prescribing After General Surgical Operations. Ann Surg, 2018. 267(3): p. 468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keller DS, Zhang J, and Chand M, Opioid-free colorectal surgery: a method to improve patient & financial outcomes in surgery. Surg Endosc, 2019. 33(6): p. 1959–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Overview of study cohorts

• CONSORT diagram of patients eligible for, enrolled, and included in the pre-implementation and post-implementation cohorts.

• Abbreviations: ERAS = Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; PRO = patient-reported outcome; MDASI = MD Anderson Symptom Inventory

Supplementary Table 1: Patient-reported outcomes data availability at each analyzed timepoint