Abstract

Objective:

To test the premise that youth alcohol harm minimization policies (compared with abstinence policies) reduce later drinking and harmful consequences of alcohol use in young adulthood, we compared associations among adolescent alcohol use, young adult alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related harms in Victoria, Australia and Washington State, United States.

Method:

Data came from the International Youth Development Study, a longitudinal, cross-national study of the development of substance use. State-representative samples of seventh-grade (age 13) students in Victoria (n = 984, 53% female, 90% White) and Washington (n = 961, 54% female, 73% White) were surveyed in 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2014 (age 25). Participants self-reported alcohol initiation by age 15 and age 25 alcohol consumption (per the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test). Path modeling tested associations among age 15 alcohol use, age 25 consumption, and alcohol-related harms at age 25; multiple group modeling tested the equivalence of parameter estimates across states.

Results:

Age 25 alcohol consumption was lower in Washington versus Victoria and was associated with poor physical and mental health, partner conflict, substance use, criminal behavior, and violence exposure in both states equally. Living in Washington predicted lower levels of multiple alcohol-related harms at age 25 indirectly via lower age 25 alcohol consumption.

Conclusions:

Young adults growing up in Victoria reported greater alcohol consumption in young adulthood, which was associated to the same degree with the harms measured regardless of alcohol policy context. Findings support state-level policies that promote alcohol abstinence in adolescence and reduced consumption in young adulthood.

Cross-nationally, alcohol use during adolescence has been linked to a wide range of concurrent and longer term problems, including academic failure, other substance use, substance use disorder, criminal justice system involvement, and injury and death related to impaired driving (Marshall, 2014; McCambridge et al., 2011). As a consequence, a range of national and state-level policies are aimed at reducing youth alcohol misuse and/or addressing harms that commonly accompany alcohol use among youth. Multiple countries takea harm minimization approach toward adolescent alcohol use, which seeks to promote responsible drinking and minimize the likelihood of negative outcomes, such as heavy episodic drinking, police contact, and impaired driving. By contrast, other countries take a zero-tolerance, or abstinence, approach toward adolescent alcohol use, with strict prohibitions against underage drinking. The current study used longitudinal data from the International Youth Development Study (IYDS) to examine links between adolescent alcohol use, young adult alcohol use, and alcohol-related health and social problems in young adulthood in a state implementing adolescent harm minimization policies (Victoria, Australia) compared with a state implementing zero-tolerance policies (Washington State, United States).

Alcohol policy in Washington and Victoria

At the outset of the IYDS in 2002, there were significant differences between Washington and Victoria in regard to underage drinking policies (Evans-Whipp et al., 2007, 2013; Hemphill et al., 2011). In Washington, the legal drinking age was—and remains—21, and underage drinking has been strictly prohibited, regardless of adult supervision or parental permission (Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board, n.d.). In Victoria, it was—and remains—legal for adolescents to consume alcohol (e.g., provided by parents); however, youth under the age of 18 may not purchase alcohol (Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, 2009). Until 2011, it was legal for any adult to provide alcohol to a child/adolescent, without written or verbal permission of the child/adolescent's parent or guardian. Also before 2011, parents in Victoria were encouraged to teach responsible drinking through parental supervision of teen alcohol use (McMorris et al., 2007).

Adolescent alcohol use and related harms in Washington and Victoria

Prior research suggests that differences in adolescent alcohol policy between the United States and Australia, including the legal drinking age and policies about parental/adult supply of alcohol to youth, contribute to higher rates of alcohol use and related harms among Australian youth. In addition to studies based on other data sets (Grube & Nygaard, 2001; Simons-Morton et al., 2010), several prior studies using adolescent data from the current sample have shown higher rates of underage drinking, alcohol initiation by age 15, and alcohol-related harms (e.g., blackouts, arguments, or fights) at age 15 in Victoria compared with Washington (Epstein et al., 2020; McMorris et al., 2007, 2011; Toumbourou et al., 2009). With regard to minimum legal drinking age, within-country studies from the United States and Canada have demonstrated that a legal drinking age of 21 (compared with 18 or 19) is associated with lower rates of alcohol consumption and fewer traffic crashes among drivers younger than 21 compared with allowing legal use at younger ages (Wagenaar & Toomey, 2002). Last, in both Australia and the United States, parental provision of alcohol to teens has been linked to an increased likelihood of heavy drinking (Komro et al., 2007; Simons-Morton et al., 2010) and experience of alcohol-related harms (McMorris et al., 2011).

Adolescent alcohol policy and young adult alcohol misuse and related harms

The longer term implications of these different policy approaches for alcohol consumption and well-being in young adulthood are unclear (McCambridge et al., 2011). Harm reduction approaches may reduce associations between underage drinking and later alcohol consumption, for example, by promoting responsible drinking. Prior findings suggest, however, that despite harm minimization policies in Australia, higher rates of heavy or harmful adolescent drinking compared with the United States continue into adulthood (Teesson et al., 2006). For example, in prior analyses of the current data set, Epstein and colleagues (2020) found that respondents in Victoria reported higher scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) than those in Washington at age 25. Further, alcohol use initiation by age 15 (Victoria: 70%, Washington: 42%) was equally predictive of age 25 AUDIT scores in both states, suggesting that higher rates of adolescent drinking in Victoria contributed to higher AUDIT scores at age 25.

Although adolescent alcohol use seems to predict later alcohol misuse to the same degree in both harm minimization and zero-tolerance contexts, it is possible that harm minimization approaches may weaken links between adolescent or young adult alcohol misuse and harms that often accompany alcohol misuse, including other drug use, alcohol-impaired driving, antisocial behavior, mental health problems, and lack of economic participation (Booth & Feng, 2002; Burns & Teesson, 2002; Quinlan et al., 2005; Stinson et al., 2005). The goal of the current study is to address the open question as to whether social and behavioral consequences associated with young adult alcohol use may be reduced through statelevel harm minimization policies. To the extent that individuals growing up in harm minimization contexts experience weaker links between alcohol misuse and related health and social problems, harm minimization approaches would be supported. If, however, young adult alcohol misuse is related to the same degree to health and social problems in both harm minimization and zero-tolerance contexts, then one would expect to see higher levels of alcohol-related harm in states or countries with a higher prevalence of young adult alcohol misuse. This pattern of results would argue for the importance of policies targeting alcohol consumption in addition to alcohol-related harms and may argue against harm minimization approaches to adolescent alcohol use, as they may indirectly increase health and social problems in young adulthood.

Current study

This study extended prior work by Epstein and colleagues (2020), which found that alcohol initiation by age 15 was equally related to young adult alcohol misuse in Victoria and Washington. Specifically, the current study used longitudinal data from the IYDS to test whether alcohol use by age 15 and a measure of alcohol consumption at age 25 were related to the same degree in both states to a range of health and social problems at age 25. Two specific predictions of harm minimization were tested: (a) age 25 alcohol consumption would be less strongly associated with concurrent health and social problems in Victoria than Washington and (b) age 15 alcohol initiation would be less strongly related to later health and social problems in Victoria than Washington.

Method

Cross-national design

Data were collected in Victoria and Washington when respondents were ages 13, 14, 15 (Grades 7, 8, and 9; 2002–2004), and 25 years (2014). Victoria and Washington were chosen for this longitudinal, cross-nationally matched study because of their distinct alcohol and drug policy at study inception but similarity in population size, urbanization, educational participation, prosperity, and ethnic diversity. The IYDS design overcomes many of the limitations of previous cross-national studies (Roberts et al., 2007) by using an identical sampling strategy (see Participants), matched and pilot tested survey items (adjusted for language and meaning in the two states), identical survey administration and data management strategies, and experienced teams of scientists in each country to ensure cultural interpretability of the data. These matched designs and strong teams are crucial to meaningful comparison of behavior prevalence across the two states (Giommoni et al., 2017). Ethics reviews for IYDS were conducted by the University of Washington Human Subjects Institutional Review Board in the United States and by the Royal Children's Hospital Ethics in Human Research Committee and The University of Melbourne Human Ethics in Research Committee in Australia.

Participants

The IYDS sample has been described in detail previously (McMorris et al., 2007). Participants included in the current study were initially recruited, with parental consent, from Washington and Victoria in 2002 when they were in seventh grade (age 13). Within each state, public and private schools were selected using a probability proportional to size sampling procedure. To achieve a desired sample of ~1,000 seventh-grade students in each state, 60 classes in each state were chosen at random from more than 150 sampled schools. Approximately 78% of seventh-grade students in Washington and 76% of seventh-grade students in Victoria in selected classrooms were recruited into the study. Nonparticipation was less likely to be attributable to nonreturn of consent forms in Victoria (5% vs. 11% in Washington) and more likely to be due to explicit parental refusal in Victoria (19% vs. 12% in Washington). Participant demographics were representative of same-grade students in each respective state. In 2002–2004, surveys were administered in person in classrooms. Age 25 surveys were administered online. Informed assent/consent was obtained at the outset of each survey; parental permission was obtained for youth under age 18. Retention at the age 25 survey was 87% in each state. Table 1 shows sample demographics by state at age 25.

Table 1.

Descriptive information by state at age 25 (Washington n = 841; Victoria n = 866)

| Variable | M (SE) | Proportion n (%) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington | Victoria | Washington | Victoria | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Female | – | – | 450 (54%) | 457 (53%) | .761 | |

| White | – | – | 698 (73%) | 779 (90%) | <.001 | |

| High school graduate | – | – | 714 (87%) | 655 (76%) | <.001 | |

| Married | – | – | 182 (22%) | 61 (7%) | <.001 | |

| Parent | – | – | 237 (28%) | 132 (15%) | <.001 | |

| AUDIT alcohol consumption (range: 0–12) Dependent variables: Health and social problems | 3.31 (2.46) | 4.30 (2.64) | – | – | <.001 | |

| Poor physical health | – | – | 110 (13%) | 116 (14%) | .849 | |

| Poor mental health (range: 1–5) | 1.96 (0.74) | 1.93 (0.70) | – | – | .384 | |

| Financial problems | – | – | 313 (38%) | 236 (27%) | <.001 | |

| Employed | – | – | 681 (81%) | 728 (85%) | .072 | |

| Family conflict (range: 1–4) | 2.2 (0.83) | 2.1 (0.81) | – | – | .094 | |

| Partner conflict (range: 1–5) | 1.64 (0.58) | 1.61 (0.51) | – | – | .461 | |

| Past-month substance use | ||||||

| Alcohol use | – | – | 710 (87%) | 621 (85%) | .076 | |

| Daily smoking | – | – | 173 (21%) | 194 (23%) | .332 | |

| Cannabis use | – | – | 234 (28%) | 144 (17%) | <.001 | |

| Illicit/prescription drug use | – | – | 99 (12%) | 132 (15%) | .038a | |

| Drunk driving | – | – | 292 (35%) | 289 (34%) | .542 | |

| Criminal behavior | – | – | 185 (22%) | 194 (23%) | .842 | |

| Violence exposure | – | – | 178 (21%) | 176 (20%) | .657 | |

Notes: T tests assessed state differences in means; chi-square tests assessed state differences in proportions. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

With a Bonferroni correction for 12 significance tests, the difference in illicit/prescription drug use between states is nonsignificant.

Measures

The IYDS survey is an adapted version of the Communities That Care Survey (Arthur et al., 2002), which has been widely used and well validated in multiple prior studies (Arthur et al., 2002; Fleming et al., 2019; Glaser et al., 2005; Hemphill et al., 2011; Oesterle et al., 2012).

Alcohol use by age 15 was measured by combining participant self-reports of any past-month alcohol use at ages 13, 14, or 15. At each age, response options ranged from 0 (never) to 8 (40 or more times), corresponding to drinking occasions per month. Respondents who reported any use at any of the three ages were coded as having used alcohol by age 15 (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Age 25 alcohol consumption was assessed using the three AUDIT consumption items (Saunders et al., 1993). An alcohol consumption score was computed by summing responses across items (AUDIT-C; range: 0–12). Several AUDIT items measure the experience of alcohol-related harm. We chose to use the consumption measure rather than total scores including the harm items so as not to inflate associations between this measure and other measures of harm at age 25.

Participants were administered (only) the general health item from the SF-12 (Ware et al., 1996) to determine age 25 physical health; response options for the question, “In general, how would you describe your health?” ranged from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor). Responses of fair or poor were coded as 1 (otherwise 0). Mental health problems were assessed using the K-10 (Kessler et al., 2002), which captures symptoms of anxiety and depression. The 10 items (Cronbach's α = .93) were averaged to yield a combined score (range: 1–5); higher scores indicate poorer mental health.

Age 25 financial problems assessed included employment and difficulty with living expenses. Respondents were asked whether they were currently employed in a paid job (1 = yes, 0 = no). Difficulty with living expenses was assessed by asking respondents to describe their current financial situation (1 = living comfortably, 2 = doing alright, 3 = just about getting by, 4 = finding it quite difficult, 5 = finding it very difficult); respondents scoring 3 or higher were coded as experiencing financial difficulty (1; otherwise 0).

Age 25 conflict with family of origin was assessed using three items about the presence of serious arguments, family members yelling or insulting each other, and fighting over the same things repeatedly (1 = YES!, 2 = yes, 3 = no, 4 = NO!; α = .86). Conflict with romantic partner was assessed using four items tapping the frequency of arguing; anger/hostility; pushing, hitting, kicking, or shoving; and fear of partner (1 = never to 5 = always; α = .79). Items about family of origin and romantic partner, respectively, were averaged; higher scores indicate greater conflict.

Age 25 other substance use measures assessed (a) any daily smoking or (b) cannabis use in the past month (each coded 1 = yes, 0 = no), and (c) any past-month use of cocaine, psychedelics, inhalants, stimulants, Ecstasy, heroin, other illicit drugs, or prescription drugs without a prescription or in amounts larger than prescribed (1 = yes to any, 0 = no to all). Respondents also reported whether they had driven when “probably affected by” alcohol or after drinking over the legal limit in the past year (1 if yes to either, otherwise 0).

Age 25 criminal behavior and violence exposure. Respondents were asked whether they had engaged in any ofa series of 12 criminal behaviors, including fighting, assault, theft, drug selling, and fraud in the prior year. Individuals who endorsed any criminal behavior were coded as 1 (otherwise 0). Violence exposure was assessed by asking participants whether they had been physically attacked or threatened with violence in the past year (two items); any experience or threat of violence was coded as 1 (otherwise 0).

Other variables. Controls included sex (1 = female, 0 = male); race (1 = White, 0 = non-White); and, as of age 25, high school completion (1 = yes, 0 = no), marital status (1= married, 0 = unmarried), and parenthood (1 = parent, 0 = nonparent). State was dummy coded (1 = Washington, 0 = Victoria).

Analysis

Chi-square and t-test analyses of differences in means and prevalence rates of study variables by state were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). A series of 12 separate path models was estimated, one for each age 25 health and social problem measure. Multiple-group modeling in Mplus version 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011) using state as the grouping variable tested hypothesized differences in the strength of association between (a) age 25 alcohol consumption and concurrent health and social problems and (b) age 15 alcohol initiation and age 25 health and social problems (both directly and as mediated by age 25 alcohol consumption) across states. Nested model tests assessed differences in model fit when parameter estimates were free to vary between states versus when they were constrained to be equal; Wald tests were used with continuous dependent variables and the DIFFTEST procedure with dichotomous dependent variables.

Results

In the analysis sample, 63% of youth in Victoria reported alcohol initiation by age 15 compared with 37% in Washington. Table 1 shows means or prevalence of age 25 variables in the two states. Washington participants were more likely than their peers in Victoria to report being a high school graduate. Almost twice as many Washington 25-year-olds were married or parenting compared with the Victorian sample. Mean alcohol consumption scores were significantly higher in Victoria than in Washington (Cohen's d = 0.4). With regard to health and social problems, young adults in Washington were significantly more likely to report experiencing financial difficulty than their counterparts in Victoria. Although rates of cigarette use were comparable across the two states, cannabis use was more prevalent in Washington. Levels of poor physical and mental health; levels of conflict with family and partners; and rates of alcohol-impaired driving, criminal behavior, and exposure to violence were not significantly different between the two states in bivariate analyses.

Multiple group modeling showed that, contrary to hypotheses, associations between (a) age 25 alcohol consumption and age 25 alcohol-related harms, as well as both (b) direct and (c) indirect effects of age 15 alcohol use on age 25 alcohol-related harms were able to be constrained to be equal across states without significant decrement to model fit (Table 2). We did find, however, that some demographic variables were differentially related to age 25 outcomes across states (Supplemental Tables A and B, Supplemental Figures A–C). (Supplemental material appears as an onlineonly addendum to this article on the journal's website.) Specifically, being a parent predicted a higher likelihood of poor mental health in Victoria but not Washington. Being female was more positively related to family conflict, and more negatively related to alcohol-impaired driving in Victoria compared with Washington. Being White was more negatively related to family conflict in Victoria compared with Washington. Accordingly, participants from both states were pooled for the final analyses, with state included as a main effect. To address the few identified state differences in pooled analyses, we included parent-by-state, sex-by-state, and race-by-state interaction terms as necessary in the path models for poor physical health, family conflict, and alcoholimpaired driving (Supplemental Figure D).

Table 2.

Tests of model equivalence across states

| Alcohol-related harm outcome | DIFFTEST chi-square (df) | Wald test statistic (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor physical health (Model 1) | 16.93 (14) | – | .260 |

| Poor mental health (Model 2) | – | 17.51 (12)a | .131 |

| Financial problems (Model 3) | 14.82 (13) | – | .319 |

| Employed (Model 4) | 18.58 (13) | – | .137 |

| Family conflict (Model 5) | – | 14.79 (11)b | .193 |

| Partner conflict (Model 6) | – | 15.25 (13) | .292 |

| Past-month substance use | |||

| Daily smoking (Model 7) | 11.59 (13) | – | .561 |

| Cannabis use (Model 8) | 9.59 (13) | – | .727 |

| Illicit/prescription drug use (Model 9) | 8.13 (13) | – | .835 |

| Drunk driving (Model 10) | 18.22 (12)c | – | .109 |

| Criminal behavior (Model 11) | 10.93 (12) | – | .535 |

| Violence exposure (Model 12) | 10.00 (12) | – | .616 |

Notes: Because path models were saturated, in each unconstrained model—where parameters were free to differ across states—the chi-square value of the overall model fit was 0 with 0 degrees of freedom. Thus, they are not shown in the table.

To achieve acceptable fit in this model, the constraint holding the relationship between parenthood and poor mental health equal across states was freed.

To achieve acceptable fit in this model, the constraints holding associations between female/male and family conflict and between White/non-White and family conflict equal across states were freed.

To achieve acceptable fit in this model, the constraint holding female/male and drunk driving equal across states was freed. State-specific model results are shown in Supplemental Figures B and C.

p < .05.

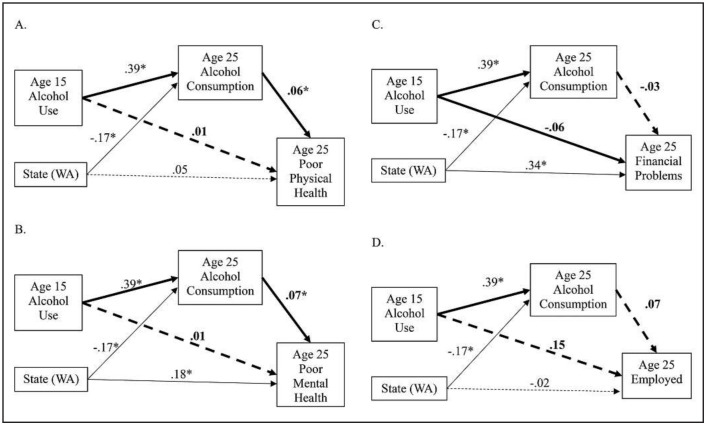

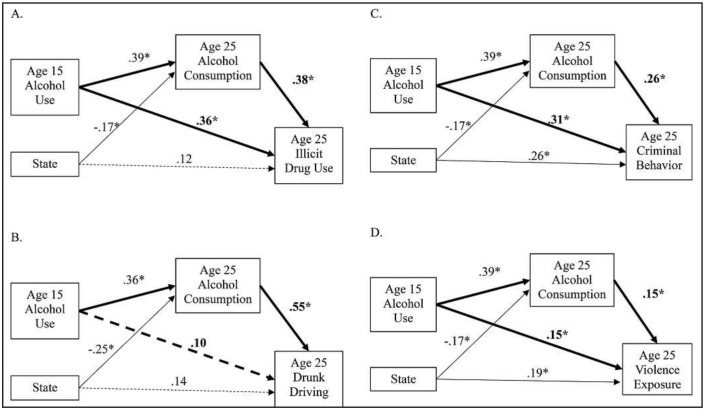

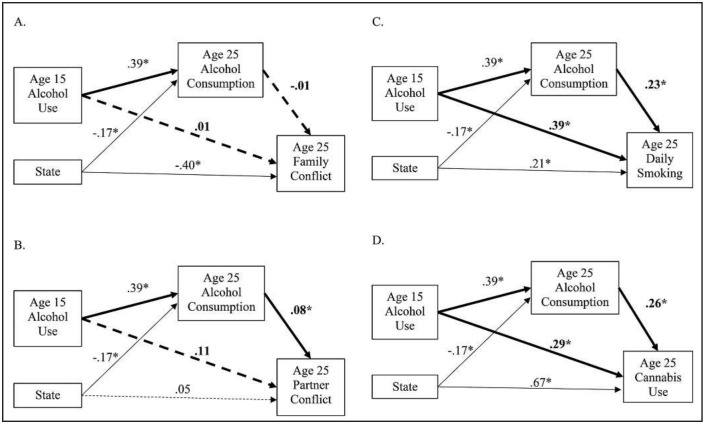

Path modeling of pooled data from both states revealed that a higher level of age 25 alcohol consumption was uniquely related to a higher likelihood of concurrent poor mental health, poor physical health, daily smoking, past-month cannabis and illicit drug use, alcohol-impaired driving, criminal behavior, and violence exposure, as well as higher levels of partner conflict (Figures 1–3). Significant indirect effects of having used alcohol by age 15 on these same outcomes also were observed. Alcohol use by age 15 also showed unique, direct effects on the probability of daily smoking, past-month cannabis and illicit/prescription drug use, criminal behavior, and violence exposure at age 25 after accounting for state, controls, and age 25 alcohol consumption.

Figure 1.

Results from final path models 1–4 (pooled across states) predicting age 25 poor physical health (yes/no; Panel A), poor mental health (mean; Panel B), financial problems (yes/no; Panel C), and employment (yes/no; Panel D). *p < .05. Solid lines indicate significant paths. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. Bolded lines show the pathways testing stated hypotheses about the direct effects of age 15 alcohol use and age 25 alcohol consumption, as well as the indirect effect of age 15 alcohol use on outcomes. Although omitted here for legibility, demographic controls were included in each model (female, White, married, parent, high school graduate; see Supplemental Figure D). The model in panel B also included a parent-by-state interaction. Parameter estimates are standardized.

Figure 3.

Results from final path models 9–12 (pooled across states) predicting age 25 illicit drug use (yes/no; Panel A), drunk driving (yes/no; Panel B), criminal behavior (yes/no; Panel C), and violence exposure (yes/no; Panel D). *p < .05. Solid lines indicate significant paths. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. Bolded lines show the pathways testing stated hypotheses about the direct effects of age 15 alcohol use and age 25 alcohol consumption, as well as the indirect effect of age 15 alcohol use on outcomes. Although omitted here for legibility, demographic controls were included in each model (female, White, married, parent, high school graduate; see Supplemental Figure D). The model in panel B also included a female-by-state interaction. Parameter estimates are standardized.

Figure 2.

Results from final path models 5–8 (pooled across states) predicting age 25 family conflict (mean; Panel A), romantic partner conflict (mean; Panel B), daily smoking (yes/no; Panel C), and cannabis use (yes/no; Panel D). *p < .05. Solid lines indicate significant paths. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. Bolded lines show the pathways testing stated hypotheses about the direct effects of age 15 alcohol use and age 25 alcohol consumption, as well as the indirect effect of age 15 alcohol use on outcomes. Although omitted here for legibility, demographic controls were included in each model (female, White, married, parent, high school graduate; see Supplemental Figure D). The model in panel A also included two interactions: female-by-state and White-by-state. Parameter estimates are standardized.

Last, in the pooled data, indirect effects of state via age 25 alcohol consumption on health and social problem variables were tested using the MODEL INDIRECT procedure. We found small but statistically significant indirect effects of living in Washington compared with Victoria. Living in Washington predicted lower levels of poor mental health, partner conflict, daily smoking, past-month cannabis and illicit drug use, alcohol-impaired driving, criminal behavior, and violence exposure because age 25 alcohol consumption scores were lower in Washington. Supplemental Tables A and B show full results for each model.

Discussion

The current study used cross-national data from Victoria, Australia, and Washington State, United States, to test two predictions of a harm minimization approach to underage drinking: (a) that young adult alcohol consumption would be less closely associated with common alcohol-related harms in Victoria than Washington, and (b) underage drinking would be less strongly related to later health and social problems in Victoria than Washington.

The current findings fall squarely within the overall pattern of findings from the IYDS, which are not consistent with predictions or goals of harm minimization. In the current analyses, levels of alcohol consumption in young adulthood were higher in Victoria than Washington, with a Cohen's d of 0.4, suggesting a moderate effect size. Links between (a) young adult alcohol consumption and (b) underage alcohol use and the experience of young adult alcohol-related health and social problems were not weakened in Victoria, suggesting that alcohol-related harms were not reduced as hypothesized. In fact, the small but statistically significant indirect effects of state observed here suggest that having grown up in Washington, as opposed to Victoria, contributed to lower rates of health and social problems among young adults through lower levels of alcohol consumption in young adulthood.

Similarly, prior IYDS analyses have found, compared with Washington, higher rates of alcohol use (use/nonuse, frequency, quantity, binge drinking) in Victoria at every assessment, spanning ages 13–15 and 25 (Heerde et al., 2019; McMorris et al., 2007, 2011). With regard to the specific harm minimization strategy of teaching adolescents responsible drinking in the home, prior analyses of IYDS adolescent data showed that adult-supervised drinking in eighth grade (age 14) predicted higher levels of alcohol-related harms (e.g., blackouts, vomiting, behavior later regretted) 1 year later; this association was equally strong in Victoria and Washington (McMorris et al., 2011).

That said, the current analyses do not permit definitive conclusions as to the relative effectiveness of harm minimization and zero-tolerance approaches to alcohol control. Multiple alcohol policy differences between the two states that are not directly grounded in harm minimization may explain the pattern of findings. Crucially, the minimum alcohol purchase age is younger in Victoria (age 18) compared with Washington (age 21), which may lead to earlier onset and higher levels of young adult drinking and alcohol-related harms (Lam, 2020; Wagenaar & Toomey, 2002). Similarly, policy differences may result in greater alcohol availability for adolescents and adults in Victoria and contribute to the observed findings.

For example, at the time of the age 25 data collection, there were 969 “late night” alcohol outlets in Victoria that operated outside normal alcohol sales hours, up to 24 hours per day (Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, 1998, 2020); no such outlets were permitted in Washington (Washington State Legislature). In addition, differences in cultural norms and population-level alcohol use, rather than policy per se, may help explain observed differences in alcohol use between the two states. For example, our prior research showed much higher rates of parent, peer, and individual attitudes favorable to alcohol use in Victoria compared with Washington (Hemphill et al., 2011), and population-level data show higher rates of alcohol use in Australia compared with the United States (Teesson et al., 2006).

Policy in both states continues to change

Despite the caveats noted above, Victoria and other states in Australia made significant changes to policies on underage alcohol use between 2010 and 2014 based in part on prior findings from the IYDS and other studies. Specifically, legal changes mandated that adults were no longer permitted to supply alcohol to underage youth unless they were a parent or guardian or had permission of a parent or guardian. Guidelines from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council around underage consumption also have become stricter, evolving from encouraging parents to teach underage youth responsible drinking in the home in 2001, to recommending delaying initiation for as long as possible in 2009, to recommending in 2020 that youth under age 18 not drink alcohol (Lam, 2020; National Health and Medical Research Council, 2019). These policy and national guideline changes were accompanied by drastic reductions in both parental provision of alcohol to underage youth and in the proportion of 14- to 17-year-olds who reported ever using alcohol and ever consuming a full alcoholic drink (Kelly et al., 2016; Rowland et al., 2018a, 2018b). Additional monitoring of youth and young adult alcohol use and additional cross-national comparison studies will be critical to assess the impact of these alcohol policy changes.

In 2012, Washington legalized the possession and use of nonmedical (recreational) cannabis for adults ages 21 and older; retail cannabis stores opened in 2014. It is unclear as yet whether young adult cannabis use is increasing postlegalization (Cerda et al., 2020; Kerr et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017); however, cannabis and alcohol use in young adulthood are strongly correlated and often co-occur (Agrawal et al., 2012; Bailey et al., 2014; Patrick et al., 2018). Cannabis use also has been linked to many of the harms examined here (Dutra et al., 2018; Epstein et al., 2015; Fergusson & Boden, 2008; Guttmannova et al., 2017; Hall, 2009). Thus, it is possible that cannabis legalization may have either increased rates of alcohol consumption and harms or changed the association between alcohol consumption and harms in the Washington sample, but not the Victorian sample, as cannabis use remains illegal in Victoria. Still, we found higher rates of alcohol use in Victoria and highly similar patterns of association between alcohol consumption and harms. In addition, very few cannabis stores had opened by the end of 2014 when age 25 data were being collected. Thus, we think it unlikely that the advent of cannabis legalization in Washington explains the current pattern of findings. Nevertheless, findings should be interpreted in light of this policy change.

Limitations and conclusions

We note that the current analysis treats physical and mental health, social, and behavioral problems as dependent variables predicted by alcohol misuse; however, causal ordering cannot be established based on the concurrent measures included here. Still, the current findings revealed important state differences in patterns of young adult alcohol consumption. Further, both adolescent initiation and young adult alcohol consumption were associated to the same degree with a range of other physical and mental health problems, conflict in important social relationships, other substance use, criminal behavior, and violence exposure, regardless of alcohol policy or cultural context. Given that young adult alcohol use is influenced by adolescent use (Epstein et al., 2020; Grant & Dawson, 1997; Guttmannova et al., 2011), and given the range of problems that are associated with young adult alcohol misuse, alcohol policy should promote abstinence from alcohol for teens, even adult-supervised use (McMorris et al., 2011), and aim to reduce consumption in young adulthood.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity of the participants in the International Youth Development Study, the dedication of the data collection teams in Australia and the United States, and the editorial contribution of Tanya M. Williams.

Footnotes

This article was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1047902), the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA012140), and the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA025029). The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of this report; or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. Conclusions reflect the points of view of the authors and not the funding agencies. The authors have no conflicts to declare. An earlier version of this research was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research in Washington, DC, May 29–June 1, 2018.

References

- Agrawal A., Budney A. J., Lynskey M. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: A review. Addiction. 2012;107:1221–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur M. W., Hawkins J. D., Pollard J. A., Catalano R. F., Baglioni A. J., Jr. (2002Measuring risk and protective factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors: The Communities That Care Youth Survey Evaluation Review 26575–601.doi:10.1177/0193841X0202600601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. (2009Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol Canberra, Australia: Author [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. A., Samek D. R., Keyes M. A., Hill K. G., Hicks B. M., McGue M., Hawkins J. D. General and substance-specific predictors of young adult nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder, and problem behavior: Replication in two samples. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2014;138:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.023. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth B. M., Feng W. The impact of drinking and drinking consequences on short-term employment outcomes in at-risk drinkers in six southern states. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2002;29:157–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02287702. doi:10.1007/BF02287702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns L., Teesson M. Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well Being. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00220-x. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M., Mauro C., Hamilton A., Levy N. S., Santaella-Tenorio J., Hasin D., Martins S. S. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:165–171. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3254. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L. M., Parish W. J., Gourdet C. K., Wylie S. A., Wiley J. L. Medical cannabis legalization and state-level prevalence of serious mental illness in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) 2008–2015. International Review of Psychiatry. 2018;30:203–215. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1467385. doi:10.1080/09540261.2018.1467385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M., Bailey J. A., Furlong M., Catalano R. F., Toumbourou J. W. Does adolescent alcohol harm minimization policy exposure reduce adult alcohol problems? A cross-national comparison. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;66:713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.019. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M., Hill K. G., Nevell A. M., Guttmannova K., Bailey J. A., Abbott R. D., Hawkins J. D. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood: Environmental and individual correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:1650–1663. doi: 10.1037/dev0000054. doi:10.1037/dev0000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Whipp T. J., Bond L., Toumbourou J. W., Catalano R. F. School, parent, and student perspectives of school drug policies. Journal of School Health. 2007;77:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00183.x. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Whipp T. J., Plenty S. M., Catalano R. F., Herrenkohl T. I., Toumbourou J. W. The impact of school alcohol policy on student drinking. Health Education Research. 2013;28:651–662. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt068. doi:10.1093/her/cyt068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Boden J. M. Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming C. M., Eisenberg N., Catalano R. F., Kosterman R., Cambron C., Hawkins J. D., Watrous J. Optimizing assessment of risk and protection for diverse adolescent outcomes: Do risk and protective factors for delinquency and substance use also predict risky sexual behavior? Prevention Science. 2019;20:788–799. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-0987-9. doi:10.1007/s11121-019-0987-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giommoni L., Reuter P., Kilmer B. Exploring the perils of cross-national comparisons of drug prevalence: The effect of survey modality. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;181:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.027. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R. R., Van Horn M. L., Arthur M. W., Hawkins J. D., Catalano R. F. Measurement properties of the Communities That Care® Youth Survey across demographic groups. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2005;21:73–102. doi:10.1007/s10940-004-1788-1. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Dawson D. A. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. doi:10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube J. W., Nygaard P. Adolescent drinking and alcohol policy. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2001;28:87–131. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmannova K., Bailey J. A., Hill K. G., Lee J. O., Hawkins J. D., Woods M. L., Catalano R. F. Sensitive periods for adolescent alcohol use initiation: Predicting the lifetime occurrence and chronicity of alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:221–231. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.221. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmannova K., Kosterman R., White H. R., Bailey J. A., Lee J. O., Epstein M., Hawkins J. D. The association between regular marijuana use and adult mental health outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;179:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.016. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. The adverse health effects of cannabis use: What are they, and what are their implications for policy? International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.013. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerde J. A., Bailey J. A., Toumbourou J. W., Catalano R. F. Longitudinal associations between the adolescent family environment and young adult substance use in Australia and the United States. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00821. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill S. A., Heerde J. A., Herrenkohl T. I., Patton G. C., Toumbourou J. W., Catalano R. F. Risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use in the United States and Australia: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.017. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A. B., Chan G. C. K., Weier M., Quinn C., Gullo M. J., Connor J. P., Hall W. D. Parental supply of alcohol to Australian minors: An analysis of six nationally representative surveys spanning 15 years. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:325–332. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3004-2. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D. C., Bae H., Phibbs S., Kern A. C. Changes in undergraduates’ marijuana, heavy alcohol, and cigarette use following legalization of recreational marijuana use in Oregon. Addiction. 2017;112:1992–2001. doi: 10.1111/add.13906. doi:10.1111/add.13906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Andrews G., Colpe L. J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D. K., Normand S. L., Zaslavsky A. M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalence and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. doi:10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro K. A., Maldonado-Molina M. M., Tobler A. L., Bonds J. R., Muller K. E. Effects of home access and availability of alcohol on young adolescents’ alcohol use. Addiction. 2007;102:1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T. How should we regulate the way young people are introduced to alcohol? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;66:645–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.021. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E. J. Adolescent alcohol use: Risks and consequences. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49:160–164. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt180. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agt180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J., McAlaney J., Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: A systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8:e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris B. J., Catalano R. F., Kim M. J., Toumbourou J. W., Hemphill S. A. Influence of family factors and supervised alcohol use on adolescent alcohol use and harms: Similarities between youth in different alcohol policy contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:418–428. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.418. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris B. J., Hemphill S. A., Toumbourou J. W., Catalano R. F., Patton G. C. Prevalence of substance use and delinquent behavior in adolescents from Victoria, Australia and Washington State, United States. Health Education and Behavior. 2007;34:634–650. doi: 10.1177/1090198106286272. doi:10.1177/1090198106286272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. M., Rosenman R., Cowan B. W. Recreational marijuana legalization and college student use: Early evidence. SSM-Population Health. 2017;3:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998–2011. Mplus user's guide. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra, Australia: Author; 2019. Draft Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S., Hawkins J. D., Steketee M., Jonkman H., Brown E. C., Moll M., Haggerty K. P. A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent drug use and delinquency in the United States and the Netherlands. Journal of Drug Issues. 2012;42:337–357. doi: 10.1177/0022042612461769. doi:10.1177/0022042612461769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Kloska D. D., Terry-McElrath Y. M., Lee C. M., O’Malley P. M., Johnston L. D. Patterns of simultaneous and concurrent alcohol and marijuana use among adolescents. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44:441–451. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1402335. doi:10.1080/00952990.2017.1402335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan K. P., Brewer R. D., Siegel P., Sleet D. A., Mokdad A. H., Shults R. A., Flowers N. Alcohol-impaired driving among U.S. adults, 1993–2002. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.006. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C., Currie C., Samdal O., Currie D., Smith R., Maes L. Measuring the health and health behaviours of adolescents through cross-national survey research: Recent developments in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. Journal of Public Health. 2007;15:179–186. doi:10.1007/s10389-007-0100-x. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B., Abraham C., Carter R., Abimanyi-Ochom J., Kelly A. B., Kremer P., Toumbourou J. W. Trial protocol: A clustered, randomised, longitudinal, type 2 translational trial of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm among adolescents in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2018a;18 doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5452-3. Article No. 559. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5452-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland B., Williams J., Smith R., Hall J. K., Osborn A., Kremer P., Toumbourou J. W. Social marketing and community mobilisation to reduce underage alcohol consumption in Australia: A cluster randomised community trial. Preventive Medicine. 2018b;113:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.032. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la Fuente J. R., Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B., Pickett W., Boyce W., ter Bogt T. F. M., Vollebergh W. Cross-national comparison of adolescent drinking and cannabis use in the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2010;21:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson F. S., Grant B. F., Dawson D. A., Ruan W. J., Huang B., Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M., Baillie A., Lynskey M., Manor B., Degenhardt L. Substance use, dependence and treatment seeking in the United States and Australia: A cross-national comparison. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.007. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumbourou J. W., Hemphill S. A., McMorris B. J., Catalano R. F., Patton G. C. Alcohol use and related harms in school students in the United States and Australia. Health Promotion International. 2009;24:373–382. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap037. doi:10.1093/heapro/dap037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation. Liquor Control Reform Act 1998. 1998. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/in-force/acts/liquor-control-reform-act-1998/001.

- Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation. Victorian liquor licenses by category. 2020. Retrieved from https://www.vcglr.vic.gov.au/resources/data-and-research/liquor-data/liquor-licences-category.

- Wagenaar A. C., Toomey T. L. Effects of minimum drinking age laws: Review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supplement 14):206–225. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.206. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E. J., Kosinski M., Keller S. D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. doi:10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Legislature. n.d. WAC 314-11-070. Retrieved from http://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=314-11-070.

- Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board. Social hosting. Retrieved from. 2020 https://lcb.wa.gov/education/social-hosting-0.