Abstract

Background and Aims

Little is known about the presence and function of tissue-resident mesenchymal stem cells [MtSCs] within the gastrointestinal mucosa in health and inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]. The contribution of MtSCs to the generation of inflammatory fibroblasts during IBD is also poorly understood. We hypothesized that IBD-MtSCs are impaired and contribute to the generation of the pathological myofibroblasts in IBD.

Methods

In a cohort of clinically and endoscopically active IBD patients and normal controls, we used quantitative RT-PCR and stem cell differentiation assays, as well as confocal microscopy, to characterize MtSCs.

Results

Expression of two stem cell markers, Oct4 and ALDH1A, was increased in the inflamed IBD colonic mucosa and correlated with an increase of the mesenchymal lineage marker Grem1 in ulcerative colitis [UC], but not Crohn’s disease [CD]. Increased proliferation and aberrant differentiation of Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells was observed in UC, but not in CD colonic mucosa. In contrast to normal and UC-derived MtSCs, CD-MtSCs lose their clonogenic and most of their differentiation capacities. Our data also suggest that severe damage to these cells in CD may account for the pathological PD-L1low phenotype of CD myofibroblasts. In contrast, aberrant differentiation of MtSCs appears to be involved in the appearance of pathological partially differentiated PD-L1high myofibroblasts within the inflammed colonic mucosa in UC.

Conclusion

Our data show, for the first time, that the progenitor functions of MtSCs are differentially impaired in CD vs UC, providing a scientific rationale for the use of allogeneic MSC therapy in IBD, and particularly in CD.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stromal cells, stem cells, myo-/fibroblasts, inflammation, PD-L1, inflammatory bowel diseases, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease

1. Introduction

No curative treatment is currently available for inflammatory bowel diseases [IBD], and mortality remains high.1 Over the last decade, the use of mesenchymal stem cells [MSCs], and in particular adipose tissue- and bone marrow-derived MSCs [BM-MSCs], has been proposed for the treatment of IBD and their use is currently being evaluated in clinical trials. However, the status and fate of gut mucosal tissue-resident MSCs [MtSCs] in IBD remains unknown.

MtSCs are important regulators of tissue repair or regeneration, fibrosis, inflammation, angiogenesis and tumour formation.2–6 The presence of MtSCs have been observed in many tissues, such as the umbilical cord, amniotic fluid, placenta, joint synovium, synovial fluid, dental pulp, endosteum periosteum and adipose tissue.7,8 MtSCs are generally classified as being negative for the haematopoietic markers, but positive for CD73, 90 and 105. These cells show low immunogenicity due to their poor expression of MHC II, CD80 and CD86, but high expression of B7-negative co-stimulators PD-L1 and PD-L2, as well as several immunosuppressive soluble factors such as IDO and PGE2.8–10

With regard to the gastrointestinal mucosa, the presence of intestinal MtSCs in preneonatal and adult healthy mice was detected in situ in the small intestine.11 Although definitive lineage tracing studies in the colon have not been reported, MtSCs are considered to be precursors of lamina propria fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.11 An animal transgenic study suggests that normal MtSCs can also differentiate into myo-/fibroblasts [MFs].11 However, very limited information is available regarding MtSCs in the human gastrointestinal tract under homeostasis and IBD.12,13

Signore et al.12 and Messina et al.13 reported the presence of CD146+ MSC-like cells in human normal adult colonic tissues. However, identification markers and the MtSC isolation methodology used overlapped those for isolation of the classical MF population.10–12 Signore et al.12 demonstrated that isolated and cloned CD146+ MtSC-like cells from healthy colonic mucosa were capable of differentiation into osteoclasts. However, in contrast to BM-MSCs, these isolated CD146+ MtSCs had low chondrogenic differentiation capacity, and complete absence of adipogenic differentiation capacity.12 Thus, it was suggested that while BM-MSCs might be more complete progenitors, colonic MtSCs are rather restricted precursors. It has been also proposed that MtSCs in Crohn’s disease [CD] might be exhausted or diverted from their normal physiological functions.12,14,15 It has also been recently noted that CD146+ MtSC-like cells express a high level of MHC class II molecules in inflamed CD colonic mucosa, a property that enhances immune activation.13

Similar to MtSCs, normal colonic MFs, which are believed to be the early progeny of MSCs, are immunosuppressive and contribute to mucosal tolerance.16–18 By contrast, the anti-inflammatory functions of these cells are switched to proinflammatory during the immunopathogenesis of IBD.16,17,19 The mechanism of this switch of intestinal MFs in IBD from immunosuppressive to an inflammatory function is unknown. However, because differentiation of human MSCs to MFs has been assumed to be the default pathway, perhaps the switch from suppression to inflammation occurs as the MtSCs differentiate toward MFs in the specific IBD inflammatory microenvironment.

Despite a lack of basic and translational research on gut-resident MtSCs, it is clear that MFs and probably MtSCs play important roles in gut mucosal homeostasis and IBD. Thus, herein we evaluated the hypothesis that MtSC number and function are impaired in chronic inflamed IBD mucosa and contribute to the appearance of the ‘pathological MF phenotype’. We demonstrate that the progenitor function of the MtSC is differentially impaired in CD vs ulcerative colitis [UC] colonic mucosa. We observed that stem cell markers Oct4 and ALDH1A were increased in IBD and positively correlated with the increase of the mesenchymal lineage marker Grem1 in UC, but not in CD. During in situ analysis, we observed a substantial increase in cells co-expressing Oct4 and ALDH1A in both CD and UC inflamed tissue, but co-expression of Grem1, Oct4 and ALDH1A by mesenchymal cells was mostly observed in inflamed UC and to a much lesser extent in CD. Increased proliferation and aberrant differentiation of Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells was observed in situ in UC, but not in CD colonic mucosa. Our data also suggest that aberrant differentiation of these cells probably accounts for the pathological PD-L1high mesenchymal stromal cells within the UC inflammed colonic mucosa, while an impaired self-renewal function of MtSCs may contribute to the prevalence of the inflammatory PD-L1low MFs in CD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies, recombinant protein and chemicals

Fluorochrome-conjugated human monoclonal antibodies targeting CD73 [clone AD2, BD Bioscience], CD90 [clone 5E10, BD Bioscience], CD105 [clone 266, BD Bioscience], CD146 [clone P1H12], PD-L1 [clone 29E.2A3, BioLegend], alpha-smooth muscle actin [α-SMA, clone 1A4, Sigma-Aldrich], Ki67 [clone 20Raj1, ThermoFisher Scientific] and Oct4 [clone EM92, ThermoFisher Scientific] were used. Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human Gremlin 1 and ALDH1A polyclonal antibodies were also used [respectively, Biorbit and Millipore Sigma]. Appropriate isotype controls and murine, and rabbit serum human Fc Blocker were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. LPS was purchased from InvivoGen.

2.2.Isolation of MtSCs from normal and IBD tissue

Full-thickness fresh human mucosal samples were obtained from biopsies or discarded surgical resection material of colon in compliance with protocols approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch, Pennsylvania State University and the University of Utah Institutional Review Board. Vulnerable populations [e.g. age <18 years] were not included in the study. Metadata on the tissue samples used for the analysis in this study are provided in Table 1. Normal colonic mucosal tissue from surgical resections of colon cancer patients and inflamed tissue from surgical resections of IBD patients were enzymatically digested as described previously.20 Single cell suspensions [104 to 5 × 105 cells per well] were then plated in the six-well dishes precoated with commercial MSC attachment substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions [StemCell Technologies]. Cells were cultured in Mesencult media with MSC potency supplement [StemCell Technologies] as described above. Media were exchanged every 48 h, and MSCs were split to the appropriate test media at a subconfluent stage [~7 days]. These isolated MSC-like cells were placed directly into appropriate media to test their clonogenicity as well adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation capacity. No obvious difference in function could be related to smoking status, and this possibility was not explored in detail due to the small number of samples.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Normal, N = 11 | UC*, N = 20 | CD*, N = 22 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 18–40 | 2 [18%] | 9 [45%] | 10 [45%] |

| ≥ 40 | 9 [82%] | 11 [55%] | 12 [55%] |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5 [45%] | 11 [55%] | 12 [55%] |

| Female | 6 [55%] | 9 [45 %] | 10 [45%] |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoked | 4 [36%] | 10 [52%] | 10 [45%] |

| Ex smoker | 4 [36%] | 7 [35%] | 7 [32%] |

| Current smoker | 3 [28%] | 3 [13%] | 5 [23%] |

| Location | |||

| Caecum | 9 [48%] | ||

| Right colon | 2 [18%] | 1 [4 %] | |

| Transverse colon | 3 [27%] | 2 [10%] | 1 [4 %] |

| Left colon | 2 [18%] | 5 [25%] | 2 [8 %] |

| Sigmoid/rectum | 4 [37%] | 13 [65%] | 4 [16%] |

| Colon, mixed | 5 [20%] | ||

| Therapy | |||

| 5-ASA | n/a | 3 [15%] | 0 |

| Corticosteroids | n/a | 2 [10%] | 0 |

| 5-ASA/corticosteroids | n/a | 0 [0%] | 6 [27 %] |

| Biologics | n/a | 0 [0%] | 7 [32 %] |

| Mix of biologics | n/a | 5 [23%] | |

| Corticosteroids/immunomodulators | 10 [50%] | 0 | |

| No treatment | 11 [100%] | 5 [25%] | 4 [18%] |

*All patients included in this study had active inflammatory disease with mucosal inflammation scored as moderate/severe.

2.3. BM-MSC culture

BM-MSCs were purchased from the StemCell Technologies and were passaged according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, these MSCs were plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per T25 flask or 1.0–2.5 × 106 cells per T75 flask, which were pretreated with StemCell Technologies Attachment Substrate. MSCs were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in complete Mesecult-XF medium [StemCell Technologies], which contained Mesencult-XF base supplemented with Mesencult-XF supplement [StemCell Technologies], non-essential amino acids, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin [Corning], 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10% heat-inactivated FBS [Sigma-Aldrich]. Cells were used in the experiments at passage 2–3.

2.4. MSC differentiation assays

After isolation, MSC-like cells were split into six-well plates with adipogenic or osteogenic media, or pelleted in a 15-mL conical tube with defined media for chondrogenic differentiation. The cells were then grown for 21 days in the appropriate differentiation media purchased from StemCell Technologies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then analysed for differentiation via Oil Red O [adipogenic], Alizarin Red [osteogenic] or Alcian Blue [chondrogenic] staining kits purchased from StemCell Technologies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A scoring system was developed to compare the differentiation capacity of the MSC-like cells: for each type of differentiation, cell isolates were given 2 points for survival and differentiation, 1 point for survival and limited or no differentiation, and 0 points for no survival. The mean of the sum of the lineage differentiation was calculated.

2.5. Clonogenicity assay

MtSC-like cells isolated from the mucosa of normal or IBD colonic mucosa were plated into six-well plates with MSC attachment substrate and 1 mL Mesencult media at seeding densities ranging from 0.5 × 101 up to 105 cells per plate. Total media volume was then adjusted to 2 mL for each well. Media were exchanged every 48 h and cells were cultured for 7 days. Cells were washed with PBS Ca2+Mg2+ and fixed with 70% ethanol for 20 min at room temperature. Wells were aspirated and allowed to dry and 2.5 mL of crystal violet solution [StemCell Technologies] was added to each well for 30 min, washed three times with water, and then allowed to dry. Clonogenicity was quantified by using the following scoring system: the highest dilution of the cells diluted that survived and proliferated was given 2 points, wells that had surviving cells but no proliferation were given 1 point, and wells with no surviving cells were awarded 0 points. This score was multiplied by the dilution factor number at which colonogenicity was observed.

2.6. ALDH analysis

CD90+ stem-like populations isolated from normal and IBD colonic mucosa with the MSC procedure above were examined by with the Aldefluor kit [Stem Cell Technologies] according the manufacturer’s staining protocol. Briefly, the colonic mucosal tissue was enzymatically digested as described previously20 and cells were stained using the Aldefluor kit in combination with CD90 surface stain. All samples were analysed on an LSRII flow cytometer [Millipore]. CD90+ live cell events were gated and analysed for the presence of ALDH bright cells using FACSDiva 6.3 [Becton Dickenson] software.

2.7. Real-time RT-PCR

Analysis was performed according to the two-step RT real-time PCR protocol. Briefly, cDNA was prepared using the iScriptTM cDNA synthesis kit [BioRad] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The appropriate assays-on-demand gene expression FAM labelled primer/probe mix was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Human β-actin and 18S genes were used as housekeeping genes. FastStart Universal Probe Master mix [Roche Diagnostic] was used to prepare a PCR mix according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were carried out in a 20 µL final volume using a BioRad Q5 real-time PCR machine according to the following PCR protocol: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C [one cycle], and 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C [40 cycles].

2.8. Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Frozen human colonic step sections were fixed and immunostained as described previously.16,18 Samples were then mounted in SlowFade Gold antifade reagent with DAPI [Life Science Technology]. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed using an Echo Revolve Microscope [Echo]. Confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM880 inverted laser scanning confocal/widefield microscope [Carl Zeiss].16,20 The corrected total cell fluorescence was used for quantitative analysis.

2.9. Luminex quantigene arrays

RNA from normal and both inflamed and non-inflamed IBD colonic mucosal tissue was analysed via the QuantiGene Plex Assay as per the manufacturer’s instructions [Affymetrix]. Briefly, mRNA was thawed and gently vortexed. A working mix consisting of nuclease-free water, RNA, blocking reagent, capture beads and probe sets was generated and dispensed into the hybridization plate. The hybridization plate was pressure sealed and incubated for 22 h in a shaking incubator at 54°C at 600 r.p.m. After centrifugation, the mRNA/bead solution was transferred to a magnetic separation plate and magnetic beads were added. Wash, incubation and amplification steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plate was read on a Luminex HTS 200 multiplex analyser.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, the results are expressed as the mean ± SE of data obtained from at least three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. Differences between means were evaluated by one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons and Student’s t-test for the analysis of the significance between two groups. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Associations between different stem cell markers, MF cell markers and PD-L1 surface expression were examined using Pearson correlation, linear regression and multivariant analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of stem cell markers Oct4 and ALDH1A are increased in inflamed IBD tissue

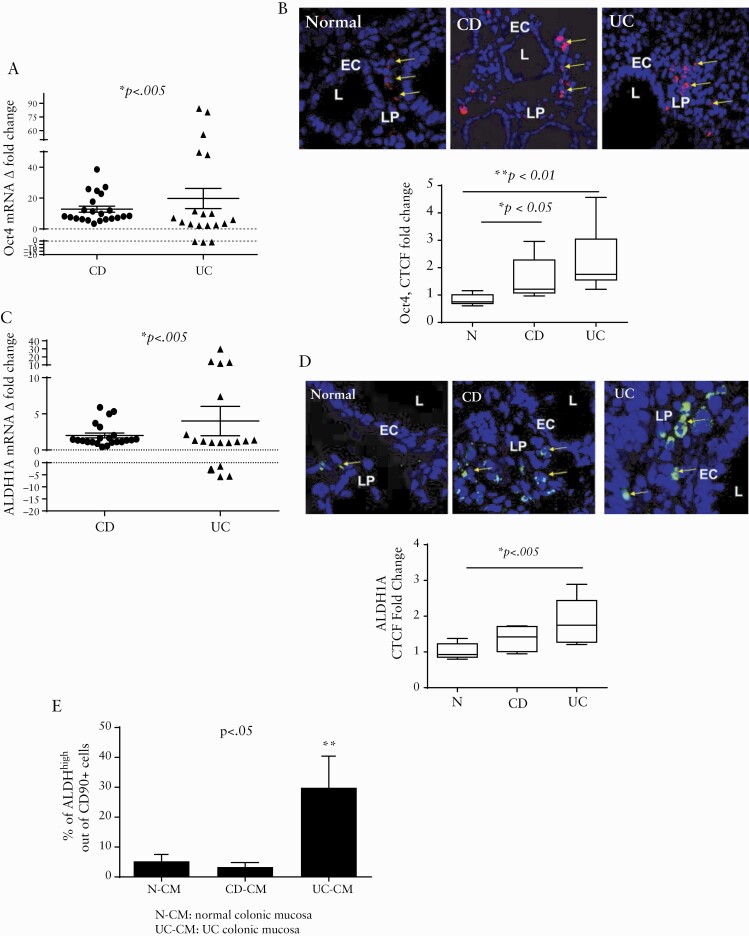

Oct4 is a master regulator transcriptional factor which is required for the stemness properties of mammalian and human stem cells. Oct4 is also essential for somatic cell reprogrammation and is tightly regulated at all stages of cell life.21–23 We observed a significant increase in mRNA expression of Oct4 in the inflamed mucosa from both UC and CD patients when compared to matched non-inflamed control tissue [Figure 1A]. Using immunostaining followed by confocal microscopy analysis we found that, when compared to normal controls, there was a significant increase in Oct4 staining in both CD and UC inflamed colonic mucosa in situ. The increase in cells expressing Oct4 protein was mostly observed in the lamina propria of the mucosa [Figure 1B].

Figure 1.

Stem cell markers Oct1 and ALDH1A are increased in the inflamed IBD colonic mucosa. [A] Oct4 mRNA levels in UC and CD colonic mucosa were compared to the non-inflamed tissue controls obtained from the same patients [real time RT-PCR analysis]. Data are shown as fold change in the expression of Oct4 and ALDH1A2 in inflamed tissue with respect to non-inflamed surrounding tissue, and means ± SEM are shown from duplicates of each tissue sample, n = 19–22 per group. [B] Normal [N] and IBD-derived colonic tissue were stained with DAPI [blue] and Oct4 [red] and analysed via confocal microscopy. Both CD and UC sections have significantly increased Oct 4 expression. Shown is a representative cross-section and summary of fold changes of corrected total cell fluorescence [CTCF] of Oct4 expression in normal, CD and UC human colonic mucosa [means ± SEM, n = 11 per group]. L, lumen; LP, lamina propria. [C] ALDH1A mRNA in UC and CD colonic mucosa was compared to non-inflamed tissue controls obtained from the same patients using real-time RT-PCR analysis. Data are shown as fold change in the expression of Oct4 and ALDH1A2 in inflamed tissue with respect to non-inflamed adjacent tissue [means ± SEM of duplicates of each tissue sample, n = 19–22 per group]. [D] Normal and IBD tissue sections were stained with DAPI [blue] and ALDH1A [green] and analysed via confocal microscopy. Both CD and UC sections show a significant increase in ALDH1A level in situ. A representative cross-section and summary of fold changes in the corrected total cell fluorescence [CTCF] of ALDH1A level in normal, CD, and UC human colonic mucosa is shown. L, lumen; LP, lamina propria [means ± SEM, n = 11 per group]. [E] Aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymatic activity is increased in CD90+ mesenchymal cells in UC, but not CD or normal tissue. Freshly digested normal [N], CD and UC colonic mucosal single cell suspensions [CM] were prepared and studied in the Aldefluor assay, combined with immunostaining for CD90 and were analysed by flow cytometry. The results are shown as mean ± SD, n = 3–5 per group.

Next we analysed expression of ALDH1A, an enzyme whose expression and activity are increased in the various types of stem cells, including MSCs.24 We found that ALDH1A mRNA level was upregulated in the inflamed IBD colonic mucosa when compared to non-inflamed matched controls [Figure 1C]. In situ analysis demonstrated that an increase in the ALDH1A protein level was observed in both IBD subtypes, when compared to healthy normal controls. However, the increase in ALDH1A mRNA reached statistical significance only in UC [p < 0.05] [Figure 1D]. ALDH activity also serves as a marker for certain stem cells that express different isoforms of this enzyme, including ALDH1A isoforms.24 Thus, we analysed changes in ALDH activity within all mesenchymal cells expressing the pan mesenchymal cell marker CD90 as a means to evaluate the stem/progenitor cells within this cell population. We found that, in contrast to the increase in total ALDH1A mRNA and protein level, ALDH activity within mesenchymal cells was significantly increased only in the inflamed UC tissue, but not in CD tissue [Figure 1E]. Together, our data indicate that during active IBD inflammation there is an increase in stem/progenitor cell markers within the mesenchymal population; however, the markers of the MSC activity are increased only in UC, but not in CD colonic mucosa.

3.2. Expression of mesenchymal lineage marker Grem1 is increased in inflamed IBD and correlates with the increase in Oct4 and ALDH1A in the colonic mucosa of UC patients

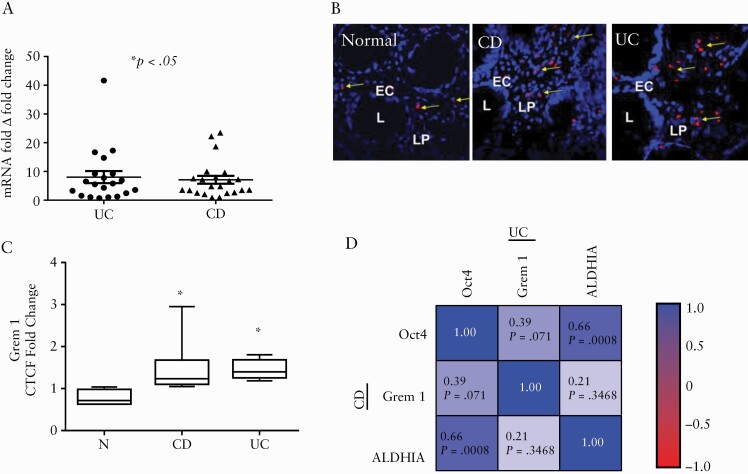

Gremlin 1 [Grem1] is a mesenchymal cell lineage marker that identifies multipotent mesenchymal progenitors in murine small intestine mucosa.11 Increased Grem1 expression has been reported in UC fibrosis.25 However, the relevance of this mesenchymal marker to the MtSCs in IBD colonic mucosa is unclear. Therefore, we next investigated the expression of Grem1 in IBD colonic mucosa and observed a significant increase in Grem1 mRNA in both CD and UC when compared to matched non-inflamed colonic mucosa from the same patient [Figure 2A]. In addition, in situ immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated an increase in Grem1 protein in the inflamed tissue from both diseases when compared to the normal colonic mucosa from healthy individuals [Figure 2B, C]. Together these results suggest that an increase in the mesenchymal stem/progenitor population occurs in the inflamed IBD colonic mucosa.

Figure 2.

Mesenchymal cell lineage marker Grem1 is increased in IBD colonic mucosa and positively correlates with stem cell markers ALDH1A and Oct4 in UC colonic mucosa. [A] Grem1 mRNA levels [real-time RT-PCR analysis] in UC and CD colonic mucosa were compared to the non-inflamed tissue obtained from the same patients [means ± SEM of duplicates of each tissue sample, n = 19–22 per group]. [B] Normal [N] and IBD-derived colonic tissue were stained with DAPI [blue] and Grem1 [red] and analysed via confocal microscopy. Both CD and UC sections have significantly increased Grem1 expression [L, lumen; LP, lamina propria]. [C] Summary of fold changes in the corrected total cell fluorescence [CTCF] of Grem1 expression in normal, CD and UC human colonic mucosa [means ± SEM, n = 9 per group]. [D] Heatmap of Pearson correlation matrix between Oct4, Grem1 and ALDH1A log mRNA fold change among CD [lower triangular correlation matrix] and UC patients [upper triangular correlation matrix].

Next, we performed matrix correlation analyses to determine the association between the mesenchymal lineage marker Grem1 mRNA and stem cell markers Oct4 and ALDH1A. Pearson correlation analyses demonstrated that positive intercorrelations between these markers among UC patients became very significant [upper triangles, Figure 2D]. In contrast, in CD patients only ALDH1A with Oct4 were positively and significantly correlated with each other [Figure 2D, lower triangles].

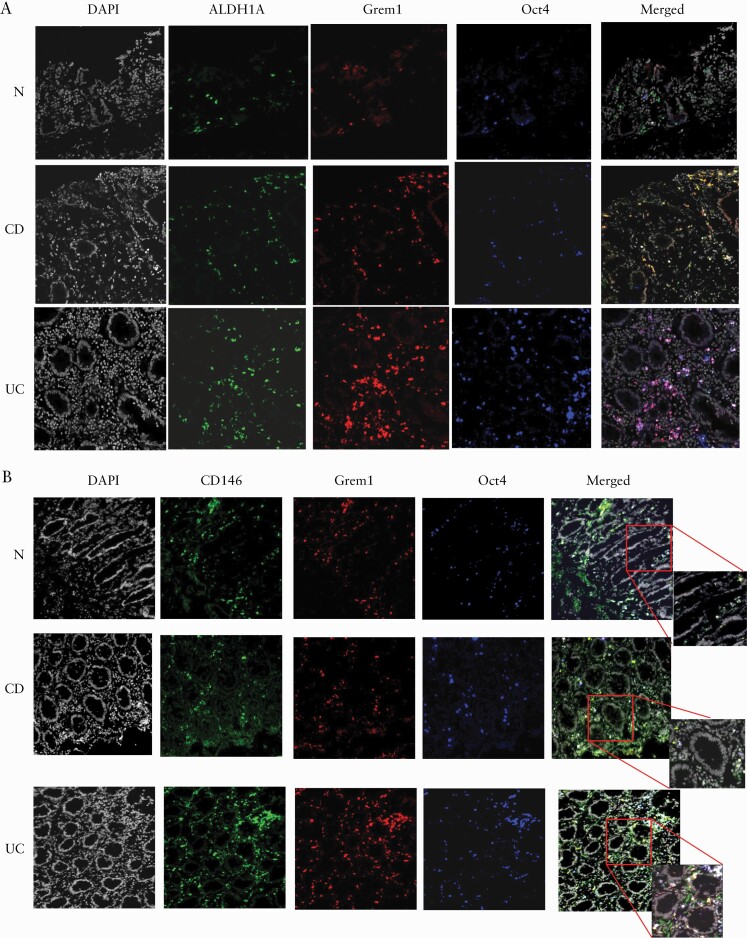

3.3. The number of Oct4+ MtSC like cells is increased in inflammed colonic mucosa from IBD patients

Very limited data are available regarding mesenchymal progenitors in the human colonic mucosa. Thus, to accurately characterize these cells in IBD colonic mucosa, we performed co-immunostaining analysis of the inflamed colonic mucosa for the classical stem cell marker Oct4 [in blue], ALDH1A [in green] and the mesenchymal lineage marker Grem1 [in red]. In situ immunofluorescence analysis of the IBD tissues for the above markers demonstrated there was a substantial increase in co-localization between Oct4 and ALDH1A in both CD and UC [cyan-turquoise colour formation, Figure 3A]. In contrast, co-expression of Grem1 by the Oct4+ALDH1A+ cells [triple co-localization] was mostly observed in UC and to a much lesser extent in CD [white colour formation on merged images, Figure 3A]. However, we observed that in CD a significant portion of Grem1+ cells expressed ALDH1A [formation of yellow–orange colour, Figure 3A]. As expected, we also observed that MtSC-like cells co-expressing Oct4 and Grem1 were positive for the mesenchymal progenitor marker CD146,12 but not all CD146-positive cells were positive for Grem1 and Oct4 [Figure 3B].

Figure 3.

[A] Oct4+Grem1+ ALDH1A+ MtSC-like cells are more prevalent in inflamed UC than in CD and normal colonic mucosa. Immunofluorescence microscopy images of representative cross-sections [n = 10 per group] from UC, CD and normal human colonic mucosa are shown. IBD and normal tissue sections were stained with ALDH1A [green], Grem1 [red], Oct4 [blue] and DAPI [grey] [n = 8–10 per group]. [B] Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells express CD146. Immunofluorescence microscopy images of representative cross-sections [n = 7 per group] from UC, CD and normal human colonic mucosa are shown. IBD and normal tissue sections were stained with CD146 [green], Grem1 [red], Oct4 [blue] and DAPI [grey].

CD146 has been suggested to be useful for the identification of MtSCs in the gut in combination with another MSC marker, CD105.12 Using in situ immunofluorescence analysis we analysed the co-localization of these markers with Oct4+ cells within IBD and normal colonic mucosa. We observed a major population of the Oct4-expressing cells that were also positive for CD146 and CD105 in UC, and to a less extent in CD colonic mucosa [Figure 4A]. As expected, we noted that only a minor portion of CD90+ cells were CD105+CD146+ cells in normal colonic mucosa, although this population was increased in the inflamed IBD tissue. We also noted that among these CD105+CD146+ cells, only a fraction expressed Oct4 [Figure 4A]. We also noted that in CD, but not UC, only a fraction of CD146+ cells was positive for both CD105 and CD90 [Figure 4B]. Together, these observations suggest that while both CD105 and CD146 are useful markers to identify mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells and to differentiate them from MFs, the addition of both, Oct4 and the pan mesenchymal marker CD90, may be useful to further differentiate MtSCs from the early mesenchymal progenitors and from other mesenchymal differentiated cells within the gut mucosa. These data further suggest that in IBD there is an increased in number of MtSC-like cells within the sites of inflammatory injury at the colonic mucosa.

Figure 4.

[A] The majority of Oct4+ cells in UC express mesenchymal progenitor markers CD105 and CD146 as compared to CD and normal colonic mucosa. Immunofluorescence microscopy images of representative cross-sections from UC, CD and normal human colonic mucosa are shown [n = 7 per group]. IBD and normal tissue sections were stained with CD146 [green], CD105 [red], Oct4 [blue] and DAPI [grey] [n = 8–10 per group]. [B] Cells co-expressing CD146 and CD105 are positive for the pan mesenchymal marker CD90 and the number is increased in UC colonic mucosa. Immunofluorescence microscopy images of representative cross sections from UC, CD and normal human colonic mucosa are shown. IBD and normal and tissue sections were stained with CD146 [green], CD105 [red], CD90 [blue] and DAPI [grey] [n = 7 per group].

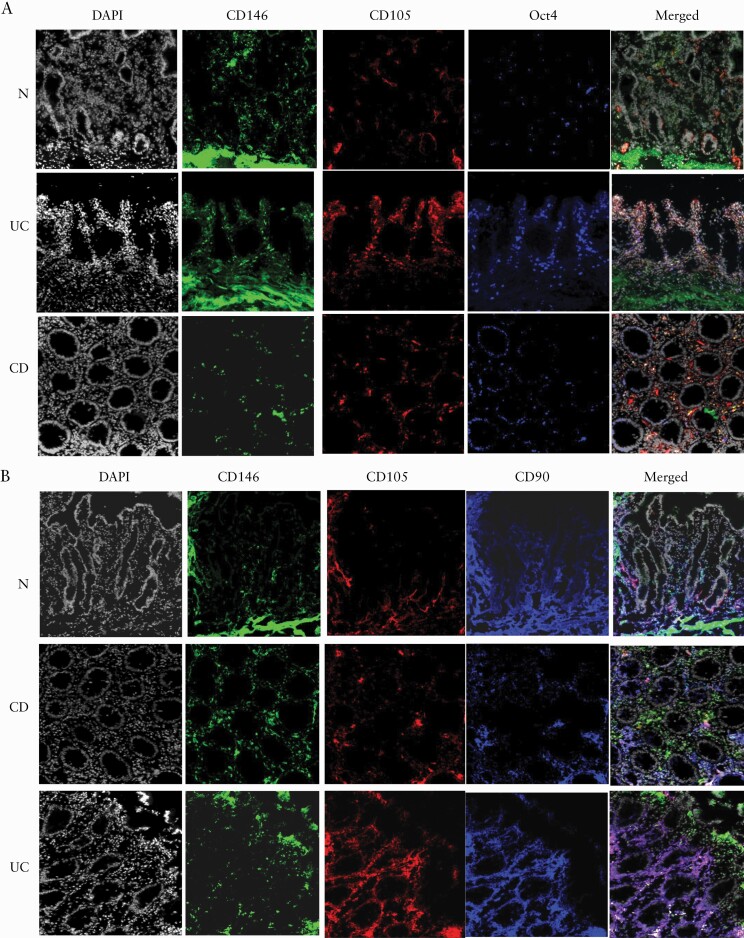

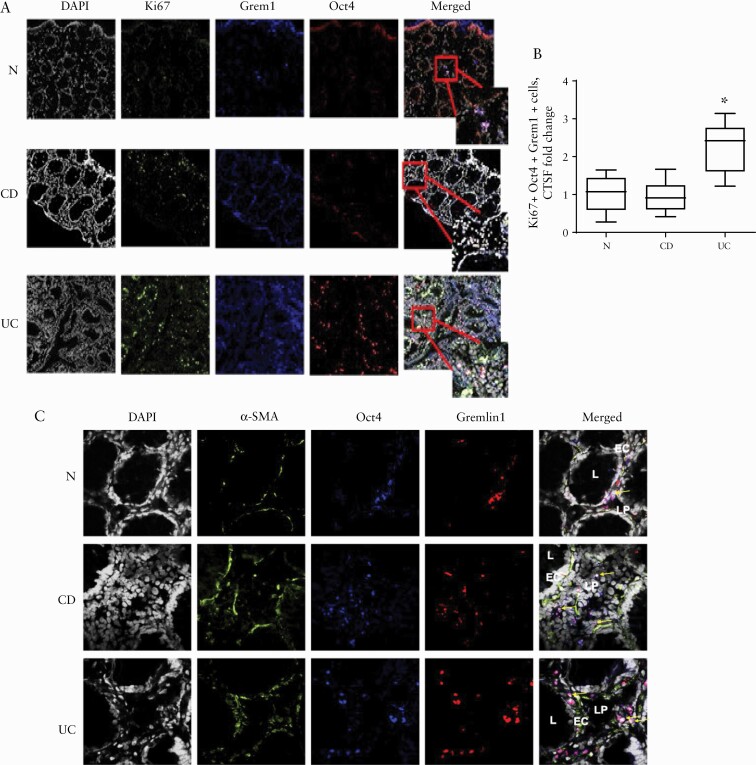

3.4. Increased proliferation and aberrant differentiation of Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells occur in UC, but not CD colonic mucosa

It has been suggested that during intestinal inflammation and radiation injury, MSCs home to and/or reposition toward the site of injury in the damaged tissue.26,27 However, it is not clear whether MSCs might also locally proliferate in the inflamed tissue. Thus, we analysed proliferation of Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells in situ by immunofluorescence labelling of the colonic mucosa with the proliferation marker Ki67. We observed that there was an increase in the proliferation of MtSC-like cells in the UC, but not CD or normal colonic mucosa [Figure 5A, B]. There was also increased co-localization of Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells with the myofibroblast differentiation marker α-SMA in UC when compared to the normal and CD colonic mucosa [Figure 5C]. Together, these data suggest that in UC, MtSC-like cells undergo increased proliferation. Further, an abnormality in the differentiation of these cells occurs in UC: while acquiring expression of the marker of differentiated myofibroblast α-SMA, there is a failure to suppress the stem cell transcriptional factor Oct4, which is normally not expressed in MFs.

Figure 5.

Proliferation and aberrant differentiation of Oct4+Grem1+ MtSC-like cells are increased in inflamed UC, but not in CD and normal colonic mucosa. [A] Confocal microscopy images of representative cross-sections from UC, CD and normal human colonic mucosa are shown. IBD and normal and tissue sections were stained for DAPI [grey], the proliferation marker Ki67 [green], Oct4 [blue] and Grem1. Triple co-localization of Oct4, Grem1 and Ki67 results in the formation of the bright pink/white colour on merged images indicated by arrows [n = 4–6 per group]. [B] Ki67 expression by Oct4+Grem1+ cells was quantified using corrected total cell fluorescence, CTSF. A summary graph is shown [means ± SEM of CTCF, n = 4–6 per group, *p < 0.005]. [C] Oct4+Grem1+ cells in UC colonic mucosa express the myofibroblast differentiation marker α-SMA. Inflamed IBD and normal colonic tissue sections were stained for DAPI [grey], α-SMA [green], Oct4 [blue] and Grem1 [red]. UC samples displayed the highest levels of triple co-localization: pink/white colour on merged images is indicated by arrows [n = 5–7 per group].

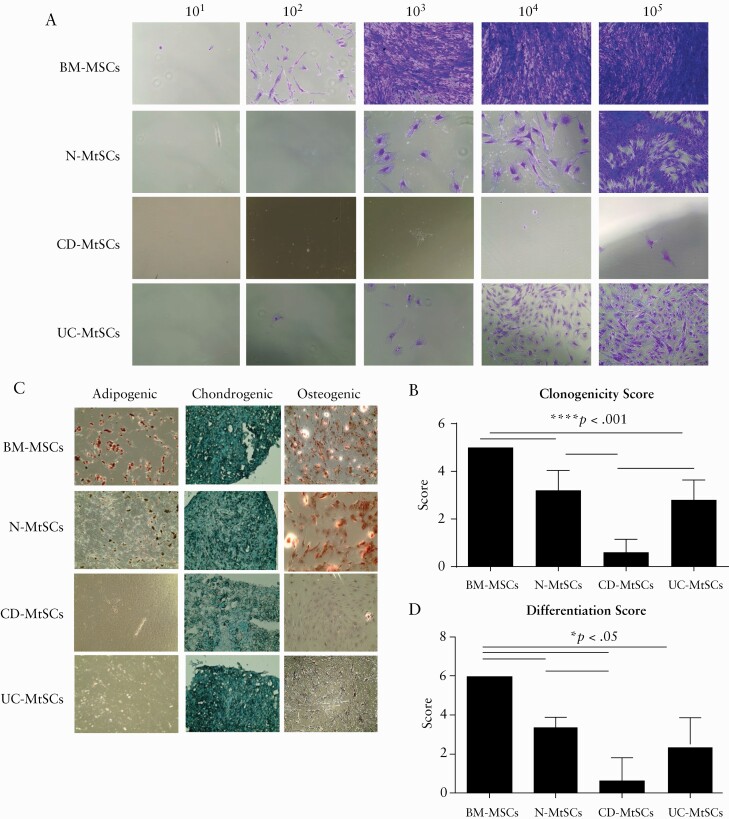

3.5. CD-derived MtSC-like cells show a dramatic decrease in clonogenic and differentiation capacity

Clonogenicity in culture is one of the major properties of MSCs and it sets them apart from differentiated cells of mesenchymal origin. Thus, we isolated MtSC-like cells from normal and colonic IBD tissue and compared their clonogenic capacity to commercial, normal BM-derived MSCs. As shown in Figure 6A, when compared to BM-MSCs, normal colonic MtSCs [N-MtSCs] had slightly lower, but sustainable clonogenic capacity. The clonogenic capacity of UC-MtSCs was further diminished when compared to BM-MSCs and N-MtSCs. Notably, CD-derived MtSC-like cells totally lacked clonogenic capacity [Figure 6A, B], further suggesting a difference between UC and CD and a profound exhaustion or derangement of CD-MtSCs.

Figure 6.

IBD-derived MtSCs have decreased clonogenic and differentiation capacities. [A] MtSCs isolated from normal and IBD colons were plated in stem cell media at seeding densities of 101–105 and stained with crystal violet on day 7. Bone marrow [BM]-derived MSCs were used as a control. Representative images are shown [n = 3–5 per group]. [B] Summary graph of the clonogenic scoring system [mean ±SEM; n = 3–5 per group]. [C] MtSCs isolated from the colons of IBD patients have decreased differentiation capacity. MtSCs isolated from normal and IBD colons were plated in special differentiation media for adipocytes, osteocytes or chondrocytes. Commercial BM-derived MSCs were used as a control. Representative images are shown [n = 3–5 per group]. [D] Summary graph of the differentiation scoring system [mean ± SEM; n = 3–5 per group].

Another unique property of stromal progenitor cells is their capacity to give rise to adipocytes, chondrocytes and osteoclasts. We therefore carried out differentiation experiments by plating normal-, UC- and CD-derived MtSCs in specific media designed to drive differentiation of the stem cells into bone, cartilage or fat cells. The results were then compared to BM-MSCs. We observed that all cell types examined were proficient in generating chondrocytes [Figure 6C, D]. However, when compared to BM-MSCs, N-MtSCs also preserved their capacity to differentiate into osteoclasts but had a reduced capacity to form adipocytes [Figure 6C, D]. In contrast, both UC- and CD-derived MtSCs completely lost their capacity to differentiate into adipocytes. However, UC-MtSCs retained some limited capacity to differentiate in osteoclasts, which was completely lost in CD-derived MtSCs. Together, our data suggest that the mesenchymal multipotency property of MtSC-like cells is reduced in UC, and almost entirely lost in CD.

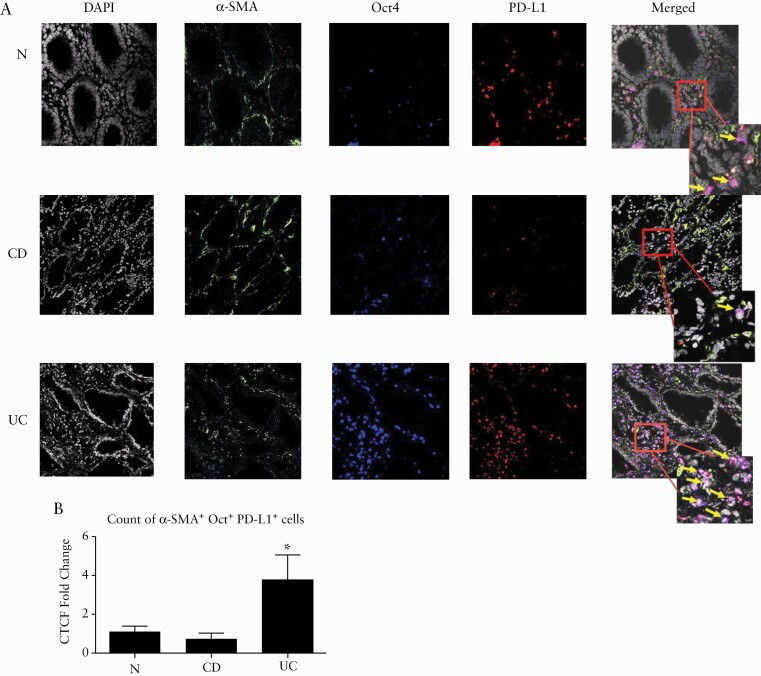

3.6. MtSCs in UC, but not CD, remain suppressive while undergoing abnormal differentiation toward myofibroblasts

Another characteristic of MSCs is their strong tolerogenic capacity due to expression of immunosuppressive molecules. One such molecule is PD-L1, a critical immune checkpoint, which is highly expressed by BM-MSCs. PD-L1 has been shown by us to be differentially expressed by α-SMA+ mesenchymal stromal cells [MFs] in inflamed colonic mucosa in IBD: PD-L1 expression was low in CD-MFs, but expression of PD-L1 was high in UC-MFs.16 Because the contribution of MtSCs to the generation of pathogenic IBD-MFs has not been explored, next we evaluated in situ expression of PD-L1 within IBD-MtSC-like cells that are undergoing differentiation to MFs [cells that are positive for both Oct4+ and α-SMA+ cells]. We observed a decrease in the overall number of cells co-expressing Oct4 [stem cell marker, in blue], α-SMA [MF marker, in green] and PD-L1 [in red] in CD [formation of the white colour on merged images, Figure 7A, B]. In contrast, in UC we observed an increase in the mesenchymal cells co-expressing Oct4, α-SMA and PD-L1 [Figure 7A, B].

Figure 7.

In UC colonic mucosa, Oct4+ cells undergo increased differentiation, acquiring a marker of fibroblast activation, α-SMA, while preserving their high expression of the immunosuppressive molecule PD-L1. [A] Representative images of human colonic mucosa derived from normal and IBD patients and immunostained for α-SMA [green], PD-L1 [blue] and Oct4 [red]. Arrows point to the triple co-localization between Oct4, α-SMA and PD-L1. [B] Oct4, α-SMA and PD-L1 co-expressing cells were quantified using corrected total cell fluorescence, CTSF. Summary graph data are expressed as means ± SEM of CTCF [n = 5–7 per group, *p < 0.05].

Additionally, we performed Spearman correlation analysis for the mRNA expression of PD-L1 and stem/mesenchymal progenitor markers Oct4, ALDH1A and Grem1. We observed significant positive correlations between these markers and PD-L1 in UC patients [Table2]. In contrast, in CD patients only ALDH1A and Oct4 were significantly correlated with changes in PD-L1 expression [Table 2]. These observations together suggest that the loss of clonogenicity and differentiation capacity and the reduction in the immunosuppressive molecule, PD-L1, are all properties of severely damaged MtSCs in CD. In contrast, UC-MtSCs are undergoing aberrant differentiation with continued expression of the stem cell markers Oct4 and Grem1 even though they are differentiating into activated myofibroblasts [αSMA marker], resulting in the formation of PD-L1high MFs in UC inflamed colon.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation between Oct4, Grem1, ALDH1A and PD-L1 mRNA expression among UC and CD patients

| Spearman correlation coefficients prob > |r| under H0: Rho = 0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 vs Oct4 | PD-L1 vs Grem 1 | PD-L1 vs ALDH1A | |

| UC |

r = 0.7484 *p < 0.0001 |

r = 0.5671 *p < 0.0091 |

r = 0.7319 *p < 0.0002 |

| CD | 0.4645 *p < 0.0294 |

0.1594 p < 0.4787 |

0.6132 *p < 0.0024 |

4. Discussion

It is well established that regenerative and immunosuppressive functions of MSCs are attractive properties of these cells for their potential use in cell-based IBD therapy.28,29 However, little is known about the contribution of tissue-resident MtSCs to the generation of the inflammatory MFs and to the immunopathogenesis of IBD. Herein, we report that multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells are present in both the normal and the IBD human colonic mucosa lamina propria and can be identified by expression of the stem cell marker Oct4 and mesenchymal lineage marker Grem1. Our data clearly demonstrate that there is a significant increase in MtSCs in UC, but only a minor increase in CD, and the progenitor function of MtSCs is differentially impaired in CD vs UC.

Our report is the first to demonstrate Oct4+ MtSCs in healthy human and IBD colonic mucosa. However, this is not without precedent; in other organs and tissues expression of Oct4 in tissue-derived MSCs has been reported.23,30,31 MtSCs derived from diseased tissues, such as endometriosis, were shown to express Oct4.30 While the exact role of Oct4 in MtSCs is poorly understood, it has been demonstrated to be crucial to the multipotency and self-renewal of overall adult stem cells.32 More recently Maragkoudaki et al. reported an increase in the OCT4B1 isoform in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and colonic tissue from a small cohort of IBD patients.33 Herein, we demonstrated that increases in the expression of the embryonic stem cell marker Oct4 positively correlates with the mesenchymal progenitor lineage marker Grem1 in inflamed CD and UC colonic tissue. ALDH1A was positively correlated with Grem1 only in UC, but not CD, and importantly, these changes were observed only in inflamed IBD tissue and not in non-inflamed IBD tissue when compared to normal healthy controls [data not shown]. Previous reports using an animal model of intestinal injury suggested that mobilization of MSCs occurs during acute intestinal and colonic injury.26,27,34 However, it remains uncertain if this increse in MSCs is due to local proliferation, repositioning from more distant mucosal sites, homing from bone marrow or perhaps all three. An increase in the various types of progenitors, including very small CD105+/STRO-1+/CD45− MSC-like and Oct-4+Nanog+SSEA−4+CXCR4+lin−CD45− embryonic-like stem cells has been observed in the peripheral blood of patients with active CD.35

We demonstrated that many of the Oct4+ cells in both normal and IBD colonic lamina propria also expressed the mesenchymal progenitors marker Grem1, confirming their mesenchymal origin. Our data also demonstrated that mesenchymal progenitors were heterogeneous within inflamed IBD mucosa, revealing both Grem1+Oct4− as well Grem1+Oct4+ cells. Recently, Kinchen et al.36 reported heterogeneity in non-haematopoietic stromal cells within the intestinal mucosa in healthy and UC colon. At least two populations of stromal cells, S3 and S4, expressed a high level of Grem1.36 Although they did not analyse the stem cell properties of these cells, they demonstrated that the S4 group was enriched in expression of genes involved in the regulation of cytokine signalling, cell adhesion and T cells.36 These properties are included in the definition of the immunosuppressive function of MSCs. While the functional significance of the Grem1 and Oct4 co-expression by colonic MtSCs remains to be defined, Grem1 plays an important role in the regulation of mesenchymal progenitor-mediated organogenesis.37–39 Thus, it is possible that co-expression of Oct4 and Grem1 is likely to be critical to the stem properties of the MtSCs and might be useful makers for detection of tissue-based mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease.

Our data support the concept of the presence of mesenchymal stem cells in IBD diseased tissue, as normal and UC-derived MtSCs are Oct4-positive, and they preserve clonogenicity, and to some degree, differentiation capacity. We observed that in CD, cells co-expressing Grem1 and Oct4 in situ were less numerous and demonstrated a dramatic decrease in their self-renewal and multipotency properties. While the mechanisms behind this damage in stem cell function in CD remain to be determined, it is possible that MtSCs in CD undergo senescence or apoptosis due to an increase in inflammation. The increase in apoptosis was previously reported for differentiated α-SMA-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells [MFs] in CD.40

A high proliferation capacity and self-renewal is another indicator of the ‘stemness’ of MSCs.9 Our data indicate that in the inflamed UC colonic mucosa, not only is the number of MtSCs strongly increased, but there is active proliferation of MtSCs [increase in the proliferation marker Ki67]. In contrast, MtSCs in normal and CD colonic mucosa are rarely Ki67+. This finding supports studies by Worthley et al.,11 showing that, in the small intestine of healthy adult mice, Grem1+ MtSC cells proliferate at a very slow but steady rate, expanding and differentiating to renew the entire subepithelial mesenchymal sheath over the period of 1 year. While further mechanistic studies are required to understand the impact of the high proliferation activity of the MtSCs in UC, it is known that increased cycles of proliferation of BM-MSCs compromise their differentiation capacity.41 In our study, we observed that MtSCs isolated from UC tissue preserved their proliferative capacity, but showed loss of adipogenic and a decrease in the osteogenic differentiation capacities. This supports the idea that increased local expansion of MtSCs in UC mucosa may lead to exhaustion of the regenerative properties of these cells.

MSCs in the colonic mucosa are thought to terminally differentiate in to fibroblasts and myofibroblasts [MFs] that secrete growth factors, cytokines and components of the extracellular matrix which are important contributors to wound healing and innate immunity.10,15,42 We recently reported abnormalities in PD-L1 expression by IBD-derived colonic CD90+ α-SMA+ mesenchymal cells, i.e. MFs. PD-L1 expression by MFs was low in CD, yet higher in UC, which in turn differentially affects the immunosuppressive function of these cells.16,19 While the mechanisms responsible for the change in this immune checkpoint expression in MFs have not been fully explored,our previous data showed that in CD, the decrease in PD-L1 by MFs was due to the decrease in PD-L1 mRNA16 as well as increased surface cleavage of this molecule.19 Herein, our data suggest that another contributor to the observed decrease in PD-L1 is due to abonormality in the CD-MtSCs that become MFs. That is, the CD-MtSCs are severly compromised, lacking regenerative and differentiation capacity, and show deminished expression of PD-L1. In contrast, MtSCs in UC appear to undergo aberrant differentiation, retaining stemness [Oct4] and high PD-L1 expression during differentiation to MFs [αSMA positivity]. It seems plausible that this may account for the appearance of pathological PD-L1high mesenchymal cells in the UC inflammed colonic mucosa previously identified by us as MFs.16 While a mechanistic link between Oct4 and PD-L1 expression by IBD-MtSCs remains to be proven, activation of OCT4 signalling is reported to be involved in the upregulation of PD-L1 expression in cancer stem cells.43 These events and others, such as activation/suppression of cleavage of PD-L1,19 may contribute to the change in the expression of the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1 by the mesenchymal cell population in IBD mucosa.

There is significant controversy in the field of MtSC research regarding the ability of certain cell markers to identify genuine stem cells from undifferentiated semi-potent cells that remain capable of differentiation into various other cell types.9,11–13 Several positive markers has been proposed to identify these cells in the peripheral tissue including Grem1, CD90, CD10511,12,35,44 and recently CD146.12,13 Our study demonstrates that partially differentiated mesenchymal progenitors stain positive for CD90, CD105 and CD146. Thus, perhaps a combination of CD90, CD105, CD146 with Grem1 and Oct4 will be helpful to identify and differentiate MtSCs from early differentiated mesenchymal cells [MFs and fibroblasts] in human normal and IBD colon.

In conclusion, our observations demonstrate that tissue-based MSCs can be isolated from normal and IBD colonic mucosa. Furthermore, the progenitor function of colonic MtSCs is differentially impaired in CD vs UC. Our study also suggests that aberrant differentiation and/or exhaustion of these cells may account for the abnormalities in the immunosuppresive function of MFs in IBD. Further studies are warranted to explore the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in causing dysfuctions of colonic MtSCs in IBD. Additional studies are required to determine whether the abnormlities in MtSCs in IBD that we have described are specific for intestinal location or type of IBD, or whether these abnormalities are common to all locations and subtypes of IBD. Finally, our data demonstrate that the ‘stem’ function of CD-MtSCs is lost while aberrant differentiation of these cells occurs in UC, providing a strong rationale for the use of healthy donor-derived allogeneic MSC-based therapy in active inflammatory CD.

Funding

Grant support: NIDDK R01DK103150, NCAT TL1TR001440 and NCI R01CA207051

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Carl Grim, PhD: study design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; manuscript preparation. Robert Noble, BS: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data. Gabriela Uribe, PhD: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data. Kamil Khanipov, PhD: statistical analysis and interpretation of data. Paul Johnson, MD: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data. Walter A. Koltun, MD: analysis and interpretation of data; clinical material support. Tammara Watts, MD, PhD: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation. Yuriy Fofanov, PhD: study concept and design; statistical analysis, manuscript preparation. Gregory S. Yochum, PhD: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation & revision for important intellectual content. Don W. Powell, MD: study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ellen J. Beswick, PhD: study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, obtained funding. Irina V. Pinchuk, PhD: study concept and design; acquisition of data; study supervision; analysis and interpretation of data; manuscript preparation & revision for important intellectual content; obtained funding.

Data Availability

The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Nocerino A, Feathers A, Ivanina E, Durbin L, Swaminath A. Mortality risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study of new york state death records. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1604–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foronjy RF, Majka SM. The potential for resident lung mesenchymal stem cells to promote functional tissue regeneration: understanding microenvironmental cues. Cells 2012;1:874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Judson RN, Zhang RH, Rossi FM. Tissue-resident mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in skeletal muscle: collaborators or saboteurs? FEBS J 2013;280:4100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Orlandi G, Bari E, Catenacci L, et al. Polyphenols-loaded sericin self-assembling nanoparticles: a slow-release for regeneration by tissue-resident mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Pharmaceutics 2020;12:381–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rolandsson S, Andersson Sjöland A, Brune JC, et al. Primary mesenchymal stem cells in human transplanted lungs are CD90/CD105 perivascularly located tissue-resident cells. BMJ Open Respir Res 2014;1:e000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spiegel JL, Hambrecht M, Kohlbauer V, et al. Radiation-induced sensitivity of tissue-resident mesenchymal stem cells in the head and neck region. Head Neck 2019;41:2892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lemos DR, Duffield JS. Tissue-resident mesenchymal stromal cells: Implications for tissue-specific antifibrotic therapies. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: when, where, and how. Stem Cells Int 2015;2015:628767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nombela-Arrieta C, Ritz J, Silberstein LE. The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011;12:126–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinchuk IV, Powell DW. Immunosuppression by intestinal stromal cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018;1060:115–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Worthley DL, Churchill M, Compton JT, et al. Gremlin 1 identifies a skeletal stem cell with bone, cartilage, and reticular stromal potential. Cell 2015;160:269–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Signore M, Cerio AM, Boe A, et al. Identity and ranking of colonic mesenchymal stromal cells. J Cell Physiol 2012;227:3291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Messina V, Buccione C, Marotta G, et al. Gut mesenchymal stromal cells in immunity. Stem Cells Int 2017;2017:8482326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mifflin RC, Pinchuk IV, Saada JI, Powell DW. Intestinal myofibroblasts: targets for stem cell therapy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011;300:G684–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pinchuk IV, Mifflin RC, Saada JI, Powell DW. Intestinal mesenchymal cells. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2010;12:310–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beswick EJ, Grim C, Singh A, et al. Expression of programmed death-ligand 1 by human colonic CD90+ stromal cells differs between ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease and determines their capacity to suppress Th1 cells. Front Immunol 2018;9:1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pinchuk IV, Beswick EJ, Saada JI, et al. Human colonic myofibroblasts promote expansion of CD4+ CD25high Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Gastroenterology 2011;140:2019–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pinchuk IV, Saada JI, Beswick EJ, et al. PD-1 ligand expression by human colonic myofibroblasts/fibroblasts regulates CD4+ T-cell activity. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1228–1237, 1237.e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aguirre JE, Beswick EJ, Grim C, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases cleave membrane-bound PD-L1 on CD90+ (myo-)fibroblasts in Crohn’s disease and regulate Th1/Th17 cell responses. Int Immunol 2020;32:57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beswick EJ, Johnson JR, Saada JI, et al. TLR4 activation enhances the PD-L1-mediated tolerogenic capacity of colonic CD90+ stromal cells. J Immunol 2014;193:2218–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zeineddine D, Hammoud AA, Mortada M, Boeuf H. The Oct4 protein: more than a magic stemness marker. Am J Stem Cells 2014;3:74–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 1998;95:379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guo X, Tang Y, Zhang P, et al. Effect of ectopic high expression of transcription factor OCT4 on the “stemness” characteristics of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019;10:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vassalli G. Aldehyde dehydrogenases: not just markers, but functional regulators of stem cells. Stem Cells Int 2019;2019:3904645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gundersen MD, Goll R, Fenton CG, et al. Fibrosis mediators in the colonic mucosa of acute and healed ulcerative colitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2019;10:e00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown SL, Riehl TE, Walker MR, et al. Myd88-dependent positioning of Ptgs2-expressing stromal cells maintains colonic epithelial proliferation during injury. J Clin Invest 2007;117:258–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ciorba MA, Riehl TE, Rao MS, et al. Lactobacillus probiotic protects intestinal epithelium from radiation injury in a TLR-2/cyclo-oxygenase-2-dependent manner. Gut 2012;61:829–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ocansey DKW, Wang L, Wang J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-gut microbiota interaction in the repair of inflammatory bowel disease: an enhanced therapeutic effect. Clin Transl Med 2019;8:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kang J, Zhang L, Luo X, et al. Systematic exposition of mesenchymal stem cell for inflammatory bowel disease and its associated colorectal cancer. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:9652817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salama E, Eldeen GN, Abdel Rasheed M, et al. Differentially expressed genes: OCT-4, SOX2, STAT3, CDH1 and CDH2, in cultured mesenchymal stem cells challenged with serum of women with endometriosis. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 2018;16:63–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matic I, Antunovic M, Brkic S, et al. Expression of OCT-4 and SOX-2 in bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells during osteogenic differentiation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2016;4:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zaehres H, Lensch MW, Daheron L, Stewart SA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Daley GQ. High-efficiency RNA interference in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2005;23:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maragkoudaki M, Vaiopoulou A, Theodoropoulos GE, et al. Specific detection of OCT4 isoforms in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Pathog 2015;7:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riehl TE, Alvarado D, Ee X, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG protects the intestinal epithelium from radiation injury through release of lipoteichoic acid, macrophage activation and the migration of mesenchymal stem cells. Gut 2019;68:1003–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marlicz W, Zuba-Surma E, Kucia M, Blogowski W, Starzynska T, Ratajczak MZ. Various types of stem cells, including a population of very small embryonic-like stem cells, are mobilized into peripheral blood in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:1711–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kinchen J, Chen HH, Parikh K, et al. Structural remodeling of the human colonic mesenchyme in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 2018;175:372–386.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dimitrov BI, Voet T, De Smet L, et al. Genomic rearrangements of the GREM1-FMN1 locus cause oligosyndactyly, radio-ulnar synostosis, hearing loss, renal defects syndrome and Cenani–Lenz-like non-syndromic oligosyndactyly. J Med Genet 2010;47:569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Capdevila J, Tsukui T, Rodríquez Esteban C, Zappavigna V, Izpisúa Belmonte JC. Control of vertebrate limb outgrowth by the proximal factor Meis2 and distal antagonism of BMPs by Gremlin. Mol Cell 1999;4:839–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Merino R, Rodriguez-Leon J, Macias D, Gañan Y, Economides AN, Hurle JM. The BMP antagonist Gremlin regulates outgrowth, chondrogenesis and programmed cell death in the developing limb. Development 1999;126:5515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Francoeur C, Bouatrouss Y, Seltana A, et al. Degeneration of the pericryptal myofibroblast sheath by proinflammatory cytokines in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2009;136:268–277.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang YK, Ogando CR, Wang See C, Chang TY, Barabino GA. Changes in phenotype and differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells aging in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018;9:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kendall RT, Feghali-Bostwick CA. Fibroblasts in fibrosis: novel roles and mediators. Front Pharmacol 2014;5:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dong P, Xiong Y, Yue J, Hanley SJB, Watari H. Tumor-intrinsic PD-L1 signaling in cancer initiation, development and treatment: beyond immune evasion. Front Oncol 2018;8:386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lama VN, Smith L, Badri L, et al. Evidence for tissue-resident mesenchymal stem cells in human adult lung from studies of transplanted allografts. J Clin Invest 2007;117:989–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.