Abstract

Halide perovskites with low-dimensionalities (2D or quasi-2D) have demonstrated outstanding stabilities compared to their 3D counterparts. Nevertheless, poor charge-transporting abilities of organic components in 2D perovskites lead to relatively low power conversion efficiency (PCE) and thus limit their applications in photovoltaics. Here, we report a novel hole-transporting low-dimensional (HT2D) perovskite, which can form a hole-transporting channel on the top surface of 3D perovskite due to self-assembly effects of metal halide frameworks. This HT2D perovskite can significantly reduce interface trap densities and enhance hole-extracting abilities of a heterojunction region between the 3D perovskite and hole-transporting layer. Furthermore, the posttreatment by HT2D can also reduce the crystal defects of perovskite and improve film morphology. As a result, perovskite solar cells (PSCs) can effectively suppress nonradiative recombination, leading to an increasement on photovoltage to >1.20 V and thus achieving >20% power conversion efficiency and >500 h continuous illumination stability. This work provides a pathway to overcome charge-transporting limitations in low-dimensional perovskites and delivers significant enhancements on performance of PSCs.

1. Introduction

Metal-halide perovskites have been tremendously developed over the past several years because they can offer the promise of easy fabrication, low-cost solution processability, flexible substrate compatibility, broad bandgap tunability, and integration possibility of tandem multijunction architecture [1–5]. Owing to the excellent intrinsic properties of perovskite materials, such as extremely high absorption coefficient and ultralong charge carrier diffusion distance, given by the unique three-dimensional (3D) ABX3 framework of perovskite polycrystals [6, 7], perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have achieved very impressive power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) already exceeding 25% [8]. Despite this remarkable achievement, however, the unacceptable vulnerability of 3D perovskites to humidity and ambient atmosphere rises to a barrier toward their market uptake. In overcoming the drawbacks, 2D and quasi-2D perovskites formed by inserting bulky organic spacer cations, which cannot fit into the octahedral network but can effectively passivate interfacial defects and vacancies outside ABX3 frameworks, have been considered as promising materials to solve the stability issue of PSCs [9–12].

2D and quasi-2D organometallic halide perovskites are formed by splitting along lattice orientations (010) and (110) from 3D perovskites, which are identified as Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) perovskites [13, 14]. These RP layered phase perovskites consist of two components: (i) layered organic phase including large molecular cations (e.g., phenylethyl ammonium (PEA) [15, 16], butylammonium (BA) [17, 18], and 1-naphthylmethylammonium (NMA)) [19] and (ii) bulky perovskite phase containing small cations (e.g., cesium (Cs), methylammonium (MA), and formamidinium (FA)) into metal halide [BX6]4− octahedral units [20, 21]. Recently, the 2D/quasi-2D halide perovskites define a promising and efficient emerging materials for solid-state photovoltaics [22–25]. However, it remains a great challenge to further advance the photovoltaic efficiencies. The relatively poor PCEs of 2D/quasi-2D PSCs are attributed to the suppression of out-of-plane charge transport by the organic cations, which acted like insulating spacers between the conducting inorganic slabs [26]. In this regard, large organic cations with outstanding charge-carrier mobilities might provide a promising way to solve the efficiency issues of 2D/quasi-2D PSCs. So far, the purposeful design on hole-transporting 2D perovskite in PSCs has not yet been reported.

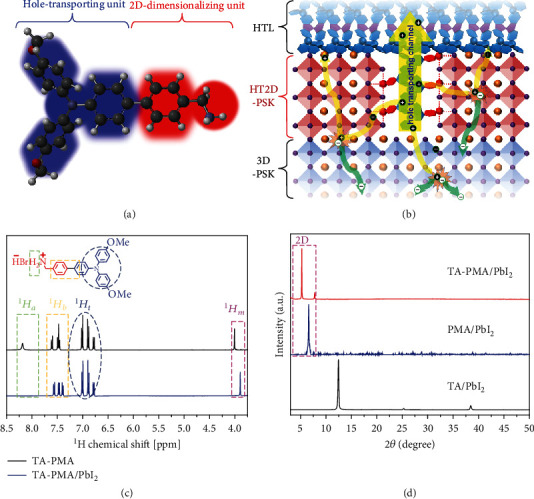

Herein, we reported a novel design strategy toward an efficient bifunctional organic salt (TA-PMA) consisting of two subunits: (i) a phenylmethylammonium (PMA) cation group (red part in Figure 1(a)) for building up RP layered phase perovskites and (ii) a triarylamine (TA) group (blue part in Figure 1(a)) for efficient hole extraction from RP perovskite to the hole-transporting layer (HTL). This tailored TA-PMA could induce a surface-2D/bulk-3D hierarchy perovskite structure, which not only can improve the stability of PSCs against damp environment due to the hydrophobic nature of formed RP perovskite but also is expected to enable a hole-transporting channel between RP perovskite slabs because of the hole-extracting ability of the TA functional group (Figure 1(b)). Moreover, the BA cation could naturally provide the desired passivation effect by forming an adduct with uncoordinated halide ions [27]. In addition, HT2D posttreatment can eliminate the miscellaneous phase of perovskite and thus improve the film morphology. Benefiting from these merits, the n-i-p planar PSC achieved a champion power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 20.71% as well as excellent operational stability exhibiting 92% of initial efficiency after 500 h continuous illumination without encapsulation.

Figure 1.

Structural analysis of TA-PMA and HT2D: (a) chemical structure of TA-PMA including a hole-transporting unit and 2D-dimensional unit; (b) illustrative scheme: TA-PMA intercalation induced formation of HT2D perovskite capping layer on 3D perovskite; (c) 1HNMR spectra of TA-PMA and TA-PMA/PbI2. The inset is the molecule structure of TA-PMA; (d) XRD patterns of TA-PMA/PbI2, PMA/PbI2, and TA/PbI2.

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of TA-PMA

The TA-PMA was synthesized from a straightforward route with simple purifications and high yields (Figure S1). The chemical structures of target TA-PMA was characterized by 1H-NMR (Figure 1(c)), presenting hydrogen signals of the ammonium group (1Ha) at 8.186 (s, 3H) ppm, the benzyl group closer to the ammonium (1Hb) at 7.616 (d, 2H) and 7.496-7.454 (m, 4H) ppm, and the triarylamine group (1Ht) at 7.022 (d, 4H), 6.902 (d, 4H), and 6.792 (d, 2H) ppm, as well as the methylene group (1Hm) at 4.009 (s, 2H) ppm, respectively, in a stoichiometric ratio. The entire 1H-NMR spectra of reaction intermediate and the product are shown in Figure S2 and Figure S3. In order to identify the interaction of TA-PMA and lead iodide (PbI2), we mixed them at a molar ratio of 2 : 1, then observed that 1Ha disappeared, and 1Hb shifted to 7.574 (d, 2H), 7.479 (d, 2H), and 7.404 (d, 2H) ppm, (1Hm) shifted to 3.895 (s, 2H) ppm, but 1Ht was almost unchanged. These chemical shifts were attributed to varying distances between protonated ammonium and neighboring hydrogens, indicating that the reaction of TA-PMA and PbI2 mainly occurred by the amine group and could potentially achieve a 2D perovskite (n = 1) phases at a molecular level. Moreover, to observe these 2D layered structures in solid state, X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of TA-PMA doped with PbI2 at a ratio of 2 : 1 (mol) were measured using phenylmethylammonium (PMA) bromide and dimethoxy-triarylamine (TA) as references under the same condition (Figure 1(d)). Only TA-PMA/PbI2 and PMA/PbI2 mixture films demonstrated significantly RP layered 2D peaks at 5.3° and 6.6° (marked in Figure 1(d)), respectively. The diffraction angle of PMA-treated 2D perovskite was similar to previous literature [28], whereas the smaller diffraction angle of TA-PMA-treated perovskite was following the tendency of its larger d-spacing distance owing to a bulkier structure than that of PMA [29]. In contrast, TA/PbI2 films displayed no extra peaks due to the lack of a reactive cation group.

2.2. First-Principle Calculations of TA-PMA/Perovskite Interface

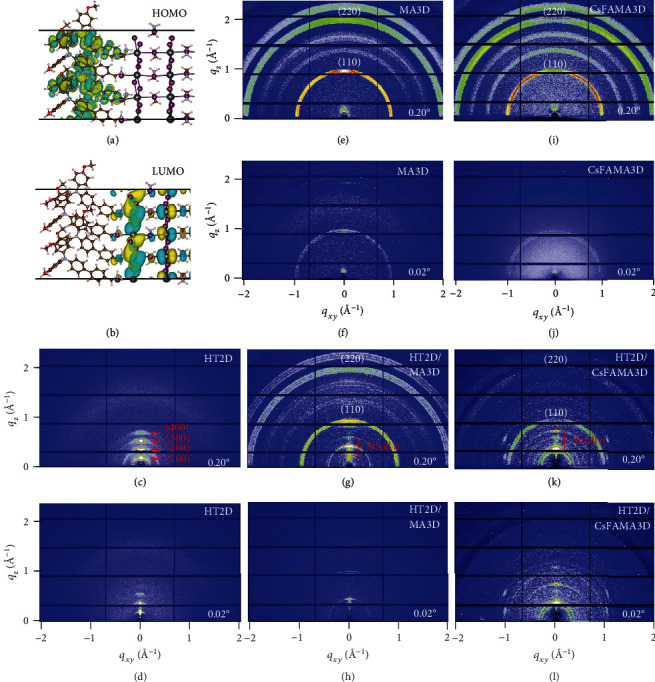

To shed light into the interface between TA-PMA and perovskite, we performed the density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The PMA cation unit in TA-PMA could fully embed into the A-site at the (010) lattice plane of ABX3 3D perovskite, even assuming maximum 100% coverage (see the CIF file and computational details in Supporting information). The pendant TA units displayed a highly orientated arrangement along with the octahedral [PbI6]4− framework with a spatial distance at ~17 Å. In order to further understand the TA-PMA orientation and packing behaviors at the MAPbI3 interface, we compared N-N atom distances at different subunits of PMA (~6.302 Å), TA (~6.401 Å), and MA (~6.435 Å) in the DFT file, respectively. These similar N-N distances could reveal a matchable interlocked structure between TA-PMA cations and MAPbI3 framework, as shown in Figure S4. Moreover, for further understanding, the interfacial charge transportation mechanism was illustrated. It is observed that the partial charge densities of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) are mainly located at the domain of TA-PMA slabs (Figure 2(a)), whereas those of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) are distributed in the perovskite region (Figure 2(b)). These obvious distinctions between HOMO and LUMO charges indicates that the hole transportation direction at the interface is from perovskite to TA-PMA. Density of state is also calculated to illustrate the electronic change (Figure S5). The relative energy difference of TA-PMA and MAPbI3 is ~1.7 eV, which is identical to the experimental energy gap between HOMO of TA-PMA (−5.6 eV) and LUMO of MAPbI3 (−3.9 eV) [30]. Herein, we named this novel structure consisting of TA-PMA and perovskite as a hole-transporting 2D perovskite (HT2D). In other words, the spontaneously grown HT2D perovskite can make a contribution to the hole extraction from the perovskite photoactive layer to the hole-transporting layer (HTL), thus restricting the interfacial charge recombination.

Figure 2.

Structure characterization of HT2D/3D hierarchy perovskite: (a, b) DFT-optimized geometries of TA-PMA/ABX3 perovskite interface and electron density plots of HOMO (a) and LUMO (b); (c, d) 2D-GIWAXS patterns of neat HT2D in the bulk phase (c) and top surface (d) with incident angle at 0.20° and 0.02°; (e–h) 2D-GIWAXS patterns of MA3D (e, f) and HT2D/MA3D (g, h) MAPbI3 films at 0.20° and 0.02°; (i–l) 2D-GIWAXS patterns of CsFAMA3D (i, j) and HT2D/CsFAMA3D (k, l) films at 0.20° and 0.02°.

2.3. Structure Characterization of HT2D/3D Hierarchy Perovskite

To investigate the hierarchy structure of HT2D/3D perovskite films, the synchrotron-based grazing-incident wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) was conducted on a series of samples, including neat HT2D perovskite, pristine 3D MAPbI3 (3D), and hierarchy HT2D/3D perovskite based on TA-PMA posttreatment (see experimental details in Supporting information). GIWAXS measurements were performed as a function of the X-ray incident angle (α), providing depth-sensitive information in 2D-scattering patterns. X-ray beam could fully penetrate the hierarchy film samples with α = 0.20°, whereas it only analyzes the top surface if under critical angle α = 0.02°. In Figures 2(c) and 2(d), a neat HT2D sample prepared by stoichiometrical TA-PMA and PbI2 exhibited scattering patterns at qz ~ 0.19, 0.38, 0.57, and 0.76 Å−1, corresponding to (100), (200), (300), and (400) crystal faces of a RP layered 2D (n = 1) perovskite, respectively. These diffraction data resulted in the lamellar stacking distance between perovskite octahedral units which was ca. 33 Å, which was in coincidence with simulated double RP layered distance as first-principle calculation results. Herein, the above HT2D (n = 1) can be formed by the following reaction):

| (1) |

In Figures 2(e) and 2(f), the MAPbI3 film demonstrated uniform 3D perovskite (110) and (220) diffraction rings in both surface and bulk phases. To form the HT2D/3D structure, TA-PMA in isopropanol (IPA) solution was spin-coated on the MA3D film and then, the posttreated film was annealed for 10 min. Figures 2(g) and 2(h) presented a direct evidence on this hierarchy HT2D/3D structure. In the bulk phase, this hierarchy HT2D/3D sample manifested obvious typical 3D perovskite (110) and (220) diffractions as well as quasi-2D diffractions at qz from 0.32 to 0.75 Å−1, attributing to small-n quasi-2D phases (n = 2, 3, 4,…) [31, 32]. Moreover, at the small grazing-incident angle, the 3D perovskite scattering intensities were significantly attenuated, whereas the layered diffraction displayed a significantly sharp peak at qz ~ 0.45 Å−1 with a narrow full width at half maxima, indicating a larger average grain size and higher ordered crystallite orientation caused by the quasi-2D perovskite phase on the top surface layer [28]. Thus, we inferred that small-n quasi-2D phases (n = 2, 3, 4,…) could be achieved by the following reaction:

| (2) |

The resultant MAI could be dissolved in IPA and further disappeared during spin-coating and thermal annealing process [33]. In the GIWAXS patterns of triple-cation perovskites (CsFAMA3D), it could also be clearly detected that pristine CsFAMA3D (Figures 2(i) and 2(j)) changed to a hierarchy HT2D/CsFAMA3D (Figures 2(k) and 2(l)) structure after the TA-PMA posttreatment.

2.4. Hole-Transporting Properties of HT2D Perovskite

In order to further investigate the hole mobility of HT2D perovskite, space-charge-limited-current (SCLC) measurements (Figure S6) based on hole-only devices were prepared as the following architecture: ITO/PEDOT:PSS/TA-PMA or HT2D/MoO3/Ag. The experimental hole mobility was significantly increased in more than one order of magnitude from 2.1 × 10−4 cm2 V−1 S−1 of TA-PMA to 2.6 × 10−3 cm2 V−1 S−1 of HT2D, which was comparable to doped Spiro-OMeTAD as HTL [34]. This enhanced hole mobility might be due to the following three reasons: (i) generally, the charge mobility of the 2D perovskite was relatively low owing to the insulating bulky organic layers which had a low hole mobility. In this work, the introduction of the triarylamine (TA) group could improve the hole mobility of the bulky organic molecules. Therefore, the TA-PMA-treated HT2D perovskite exhibited a high hole mobility. (ii) In addition, according to the DFT calculations, the TA units displayed a highly orientated arrangement along with the octahedral [PbI6]4− framework in HT2D perovskite, since the PMA cation groups in TA-PMA could fully embed into the A-site at the (010) lattice plane of ABX3 3D perovskite, whereas the molecule arrangement in the neat TA-PMA film was randomly unordered owing to the lack of perovskite framework as the template. (iii) Furthermore, the azimuth angle integration curve of HT2D diffraction peaks at q ~ 0.45 Å−1 displayed the appearance of this peak which was along the out-of-plane direction (qz) and not the in-plane direction (qxy), supporting the vertical packing of HT2D grown on substrate. These vertical packing HT2D can form a hole-transporting channel and thus perform higher hole mobility.

2.5. Morphology and Photoelectric Properties of TA-PMA Posttreatment Perovskite Films

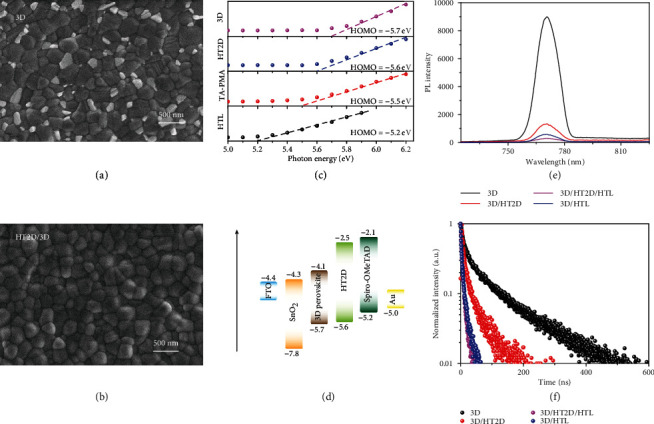

We further investigated the morphology and crystalline phase changes of CsFAMA3D perovskite films induced by TA-PMA posttreatment. To simplify, in the following discussion, CsFAMA3D is abbreviated as 3D. As shown in Figure 3(a), the top-view SEM images of controlled 3D perovskites showed that many small grains of unreacted PbI2 were distributed in the grain boundaries of perovskite polycrystals, due to the disordered growth in perovskite crystallinity during thermal annealing process [33–37]. Significantly, after TA-PMA posttreatment (Figure 3(b)), these small grains seemed to completely disappear and crystal grains were significantly enlarged, due to the process of the aforementioned reaction (equation (1) and equation (2)) and Ostwald ripening [38]. Moreover, root mean square (RMS) surface roughness estimated from AFM images (Figure S7) demonstrated that the surface of the perovskite film became smoother and more compact for TA-PMA-modified 3D perovskites, ascribing to the formation of the HT2D perovskite layer [39].

Figure 3.

Morphology and photoelectric properties of TA-PMA posttreatment perovskite films: (a, b) top-view SEM of 3D (a) and HT2D/3D (b) perovskite films; (c) PESA spectra of 3D, HT2D, TA-PMA, and Spiro-OMeTAD films; (d) schematic energy diagram of TA-PMA-posttreated PSCs, energy levels of FTO, SnO2, Spiro-OMeTAD, and Au according to reference [2]; (e, f) images showing PL (e) and TRPL (f) spectra of 3D, 3D/HT2D, 3D/HTL, and 3D/HT2D/HTL.

Besides morphology modification, the surface-HT2D structure on the bulk-3D perovskite could also affect its work function and the interfacial band alignment. We performed photoelectron spectroscopy in air (PESA) on a series of samples (Figure 3(c)), exhibiting HOMO levels at −5.7 eV for 3D perovskite, −5.6 eV for HT2D, −5.5 eV for TA-PMA, and−5.2 eV for Spiro-OMeTAD as HTL, respectively. As shown in Figure 3(d), these gradually raised energy levels of 3D/HT2D/HTL architecture could effectively improve hole extraction and suppress interfacial nonradiative recombination between light-harvesting 3D perovskite and HTL in typical configuration. Furthermore, both steady-state photoluminescence (PL) (Figure 3(e)) and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) (Figure 3(f)) spectra presented an effective enhancement on exciton/charge carrier extraction by using an intermediate HT2D layer. Compared to the 3D perovskite, the 3D/HT2D film showed a normalized PL intensity of 29.9% and calculated average PL decay time (τavg) of 45.16 ns, which should be ascribed to the hole-extracting effect of the HT2D capping layer. Furthermore, these values of 3D/HT2D/HTL film could further reduce to 7.9% and 7.15 ns, which indicated that the gradual energy levels were more advantage for hole extraction compared to traditional 3D/HTL interface (13.8% and 9.61 ns). The fitted values of τ1, τ2, A1, and A2 and the calculated τavg of the samples are summarized in Table S1.

2.6. Photovoltaic Performance and Stability

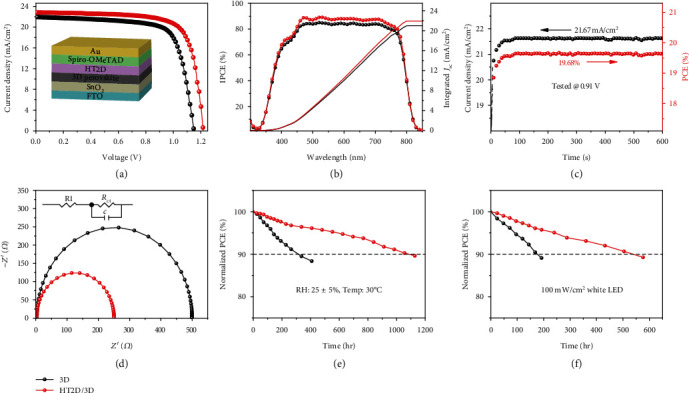

The surface-2D/bulk-3D hierarchy perovskite films were further fabricated into PSCs with a conventional planar n-i-p configuration of FTO/SnO2/perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au. Figure 4(a) listed the current density–voltage (J–V) curves of HT2D/3D- and 3D-based PSCs. Noticeably, the mixed cation PSCs based on HT2D/3D delivered a high PCE up to 20.71% compared to the pristine 3D PSCs (PCE = 18.53%), achieving a photovoltage (Voc) of 1.21 V, a current density (Jsc) of 22.81 mA cm−2, and a fill factor (FF) of 75.08%. The photovoltaic parameters of HT2D/3D PSCs were significantly enhanced with the reducing defect density of the TA-PMA-treated perovskite layers. As shown in Figure S8, the trap filled limit voltage (VTFL) of 3D and HT2D/3D perovskite films were 1.87 V and 0.70 V, respectively. According to the above logarithmic J − V analysis, the calculated defect concentration Ndefects of HT2D/3D perovskite films (7.96 × 1015 cm−3) was an order of magnitude lower than the 3D counterpart (7.52 × 1016 cm−3) [40]. The lower defect density of HT2D/3D perovskite films indicated in which fewer nonradiative recombination centers existed due to less miscellaneous phases. The PV parameters of the devices are listed in Table S2. Their typical J–V hysteresis curves are listed in Figure S9. The HT2D/3D-based PSCs showed not only enhanced PV performance but also higher reproducibility than the pristine 3D-based PSCs (Figure S10). HT2D/3D-type PSCs processed with different contents of TA-PMA were analyzed to demonstrate the effect of TA-PMA on device performance. As shown in Figure S11 and Table S3, TA-PMA-treated PSCs exhibited a synchronous enhancement of Voc, Jsc, and FF by optimizing an appropriate thickness of the HT2D layer. Nevertheless, using a similar concentration of PMA and TA as counterparts, PMA-modified PSC showed a slight enhancement on device performance, because PMA possessed only a low-dimensional unit but no improvement on hole transportation. TA-treated PSC presented even poor performance since it could not form a 2D structure and thus insulated hole extraction from perovskite to HTL (Figure S12 and Table S4). Incident photon-to-electron conversion efficiency (IPCE) measurements were carried out to validate the current densities of devices (Figure 4(b)). All IPCE spectra showed the onset of around 820 nm (~1% IPCE) and exhibited quantum efficiency values of over 80% from 400 to 780 nm. The integrated short-circuit current density (Jsc) calculated from the IPCE spectrum was 21.94 mA cm−2 for HT2D/3D PSC and 20.99 mA cm−2 for 3D PSC, which matched well (~5%) the Jsc measured under AM 1.5G illumination. Furthermore, the HT2D/3D PSC also delivered a stabilized photocurrent of 21.67 mA cm−2, corresponding to a stabilized efficiency of 19.68%, under a constant voltage bias near the maximum power point (0.91 V) (Figure 4(c)), which was very close to the J–V scan efficiency.

Figure 4.

Device performance for 3D or HT2D/3D-based PSCs: (a) conventional n-i-p PSC architecture used in this work and J − V curves of the champion PSCs measured under 1 sun AM 1.5G with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 using a 0.1 cm2 mask; (b) IPCE and the corresponding integrated Jsc for the best performing PSCs; (c) the stable output of a champion HT2D/3D-based device at a maximum power point of 0.91 V; (d) Nyquist plot of PSCs at a potential bias of 0.5 V and frequency range from 1 to 105 Hz, in the dark; (e) stability test of PSCs stored in ambient air with a relative humidity of 25 ± 5% at 30°C; (f) the photostability of PSCs under illumination of 100 mW/cm2 white LED light in N2 glove box.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyses of PSCs were carried out to further characterize the charge transfer in the full devices based on HT2D/CsFAMA3D perovskites (Figure 4(d)) [41–43]. The Nyquist plots were obtained in the dark with an applied bias voltage of 0.5 V, and the fitted parameters are summarized in Figure 4(d). As shown in the equivalent circuit, the internal series resistance (Rs) was related to the sheet resistance of the electrodes. The Rs values of the HT2D/CSFAMA3D and pristine CsFAMA3D PSCs were similar at 23.1 Ω and 31.8 Ω, respectively. On the other side, the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) generally refers to the contact resistance at all the interfaces such as the electrode/transporting layer/perovskite interface, which is corresponding to the semicircle in the high-frequency region [44]. At the Voc of 0.5 V, the Rct value of HT2D/3D PSC at 195 Ω was less than half the Rct value of pristine CsFAMA3D PSC at 489 Ω, due to its better interfacial contact and charge transportation [45, 46]. The Nyquist plots of HT2D/CsFAMA3D and pristine 3D PSCs from 0 V–0.5 V showed similar trends shown in Figure S13 and Table S5.

In addition to the enhanced PV performance, the HT2D/CsFAMA3D PSCs exhibit excellent stability. In the unencapsulated HT2D/CsFAMA3D PSCs, 91% of the initial PCE could remain and a small hysteresis between forward and reverse JV sweep existed when stored in ambient condition with RH 25 ± 5% at 30°C for 1000 h (Figure 4(e) and Table S6). Contact angle analysis suggested that the high moisture stability of the TA-PMA-treated PSCs was ascribed to the more hydrophobic surface of the 2D structure, suggested by larger contact angles (64.2°) than 3D perovskite (48.6°) when using water droplets (Figure S14) [47]. Furthermore, the HT2D/3D PSC showed better photostability and 91% of the initial PCE remained after continuous illumination with white LED light for ~500 h in dry N2 glove box, while the pristine 3D PSC was below 90% of initial PCE at 200 h (Figure 4(f)).

3. Discussion

In this work, we have designed and synthesized a novel hole transporting organic salt TA-PMA, which can induce a surface-2D/bulk-3D hierarchy perovskite structure in both MAPbI3 and mixed-cation perovskite. The resulted HT2D perovskite on the 3D-bulk film surface could regulate the interfacial band alignment, suppress the interfacial charge recombination, improve the perovskite crystallization and film morphology, and enhance the hole mobility and charge extraction ability. As a result, all the photovoltaic parameters of the HT2D/3D PSC device including Jsc, Voc, and FF were significantly enhanced, and the champion PCE of 20.71% was achieved along with the higher reproducibility than pristine 3D-based PSCs. Besides efficiency, another critical factor for photovoltaics was environmental stability and photostability under operating conditions. The stress tests demonstrated that HT2D/3D PSCs were much stabler over long-term operation against moisture and light soaking in contrast to the pristine 3D PSCs, owing to the hydrophobic nature properties of surface-2D layer. This work will offer a pathway to not only overcome the stability challenges for bulk 3D perovskite but also inspire the molecular design of novel hole-transporting 2D perovskite in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material Preparation

4-(Tert-butoxycarbonyl)benzeneboronic acid and 4-bromo-N, N-bis (4-methoxyphenyl) aniline were purchased from Energy Chemical Corp. Formamidinium iodide (FAI), methylammonium bromine (MABr), and lead iodide (PbI2) were purchased from ZhongNeng Corp. Lead bromide (PbBr2), methanaminium iodide (MAI), and Spiro-OMeTAD were purchased from Xi'an Polymer Light Technology. Other materials were bis(trifluoromethane) sulfonimide lithium salt (99.95%, Aldrich), 4-tert-butylpyridine (99.9%, TCI), FK 209 Co (III) TFSI salt (Xi' an Polymer Light Technology Corp), and SnO2 colloidal solution (15% in H2O colloidal dispersion, Alfa Aesar).

4.2. Preparation of HT2D Perovskite Films

The neat HT2D perovskite film was prepared as follows: 0.1 mmol of TA-PMA and 0.05 mmol of PbI2 were dissolved in 1 mL of DMF, spin-coated on the substrate at 3000 rpm for 30 s, and then annealed at 100°C for 10 minutes.

4.3. Preparation of HT2D/3D Perovskite Films

The hierarchy HT2D/3D perovskite film was prepared as follows: TA-PMA was dissolved in IPA in 3 mg/mL, then spin-coated on the 3D perovskite film at 3000 rpm for 30 s. The posttreated perovskite film was annealed at 100°C for 10 min.

4.4. SCLC Mobility Measurements

The hole-only device for hole mobility measurements consisted of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/TA-PMA:PbI2 (or TA-PMA)/MoO3/Ag. A preetched ITO substrate was treated with UV–ozone for 30 min, and then a 40 nm PEDOT:PSS layer was spin-coated onto the ITO substrate from an aqueous solution, followed by annealing at 150°C for 10 min. 0.1 mmol of TA-PMA and 0.05 mmol of PbI2 (or neat 0.1 mmol of TA-PMA) were dissolved in 1 mL of DMF, spin-coated on the PEDOT:PSS layer at 3000 rpm for 30 s, and then annealed at 100°C for 10 minutes on a hot stage. A bilayer cathode structure of MoO3 (20 nm)/Ag (100 nm) was thermally evaporated on top of the TA-PMA:PbI2 (or TA-PMA) film. By using the following equation, the hole mobilities of the devices were determined with the SCLC method

| (3) |

where ε0 is the permittivity of free space, εr is the dielectric constant of the TA-PMA:PbI2, μh is the hole mobility, V is the voltage drop across the device, and L is the TA-PMA:PbI2 film thickness; in formula, V = Vappl − Vr − Vbi, Vappl is the applied voltage to the device, Vr is the voltage drop due to constant resistance and series resistance across the electrodes, and Vbi is the built-in voltage due to the difference in work function of the two electrodes. The current density versus voltage characteristics were recorded on a Keithley 2400 source meter.

4.5. XRD Measurements

In order to clearly identify diffraction peaks, a simple component MAPbI3 perovskite was adopted for XRD analysis. 1 mmol MAI and 1 mmol PbI2 were dissolved in 800 μL mixed solvent of DMF/DMSO (4 : 1, by volume) as a precursor solution. The MAPbI3 perovskite films were deposited by spun a 30 μL precursor solution at 4000 rpm for 30 s with an acceleration speed of 1000 rpm. During this step, 100 μL antisolvent of ethyl acetate (EA) was dropped at the last 5th second as the antisolvent. The films were annealed at 100°C for 20 min and waited until cooling to room temperature. Then, TA-PMA (or PMA, TA) dissolved in IPA was spin-coated on the MAPbI3 perovskite film at 3000 rpm for 30 s; the posttreated perovskite film was annealed at 100°C for 10 min. The different perovskite films were tested by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advance) using CuKα radiation.

4.6. PSC Device Fabrication of Mixed Cation Perovskite

FTO glass substrates (Nippon Sheet Glass) were ultrasonically cleaned by glass detergent (1 vol% in deionized water), deionized water, acetone, and ethanol for 15 min, in sequence. Substrates were treated with UV–ozone for 30 min to remove the last traces of organic residues. For the SnO2 films, the as-purchased SnO2 colloidal dispersion was diluted by water (1 : 3 wt) and then spin-coated onto the clean FTO glass substrates at 3000 rpm for 30 s and repeated for two times, then annealed at 150°C for 30 min. The mixed CsFAMA perovskite layers were deposited by spinning a 30 μL CsFAMA perovskite solution (see preparation details as follows) in a two-step procedure at 6000 and 6000 rpm for 30 and 10 s with an acceleration speed of 1000 and 6000 rpm. During the first step, 100 μL antisolvents of EA were dropped at the last 5th second, respectively. The films were annealed at 100°C for 60 min and waited until cooling to room temperature. Then, 3 mg TA-PMA/mL IPA solution was spin-coated onto the 3D perovskite film at 3000 rpm for 30s; the posttreated perovskite film was annealed at 100°C for 10 min. A 35 μL Spiro-OMeTAD solution (see preparation details as follows) was spun on the corresponding mixed perovskite films at 3000 rpm for 30 s. Finally, 80 nm of gold was evaporated as the back electrode to form the whole devices.

4.7. Preparation of the Mixed Perovskite Precursor Solution

“(FA0.85MA0.15) Pb(I0.85Br0.15)3” was a perovskite formulation, written as “FAMA.” The FAMA-mixed perovskite precursor solution was prepared by dissolving PbI2 (1.218 M), PbBr2 (0.182 M), FAI (1.218 M), and MABr (0.182 M) in a mixed solvent of DMF/DMSO (4 : 1, by volume). 30 μL CsI solution (predissolved as a 1.5 M stock solution in DMSO) was added to the FAMA-mixed perovskite precursor to achieve the desired triple Cs0.05FA0.81MA0.14PbI2.55Br0.45 perovskite solution (labeled as CsFAMA).

4.8. Measurement and Calculation of Ndefects

We have measured and calculated the Ndefects according to the reference [8]. J − V characteristics of devices (ITO/perovskite/Au), used for estimating the SCLC defect concentration (Ndefects = 2 ɛɛ0VTFL/eL2), VTFL is the trap-lied limit voltage, ɛ and ɛ0 are the dielectric constants of perovskite and vacuum permittivity, L is the thickness of the perovskite film, and e is the elementary charge.

4.9. Instrument Details

The NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker 400 MHz instrument. The different perovskite films were tested by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advance) using CuKα radiation; the optical absorption of the perovskite samples was measured using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Lambda 750). The PESA (photoelectron spectroscopy in air) was measured with Nanjing Sunny Tech's IPS-4 Ionization Energy Measurement System. The surface morphologies and microstructures of the perovskite films were investigated using a field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Zeiss Ultra Plus). The steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra were obtained using a PL microscopic spectrometer (Flex One, Zolix, China). The time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) was measured at 780 nm using excitation with a 510 nm light pulse from Delta Flex Fluorescence Lifetime System (Horiba Scientific Com., Japan). GIWAXS experiments were performed at BL14B1 and BL16B1 beamlines at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. The photocurrent density-voltage curves of the perovskite solar cells were measured using a solar simulator (Oriel 94023A, 300 W) and a Keithley 2400 source meter. The intensity (100 mW/cm2) was calibrated using a standard Si solar cell (Oriel, VLSI standards). All the devices were tested under AM 1.5G sunlight (100 mW/cm2) using a metal mask of 0.1 cm2 with a scan rate of 10 mV/s. IPCE measurements were carried out in DC mode by using a Keithley 2400 source meter and a SOFN 7ISW752 monochromator equipped with a 500 W Xenon lamp. The wavelength sampling interval was 5 nm, and the current sampling time was 1 s, which was fully controlled by a computer. A Hamamatsu S1337-1010BQ silicon diode used for IPCE measurements was calibrated at the National Institute of Metrology, China. The EIS measurements were carried out by an EC-lab (SP300).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported financially by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFE0131900); National Natural Science Foundation of China (91833306, 91733302, 62075094, 52003118); Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (202003N4004); the Joint Research Funds of Department of Science & Technology of Shaanxi Province and Northwestern Polytechnical University (2020GXLH-Z-014); the Recruitment Program of Global Experts; the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program of Jiangsu Province; and the Six Talent Peak Project of Jiangsu Province (XNY-026). The authors thank beamline BL14B1 and BL16B1 of SSRF for providing the beamtime for data collection, and BL01B1, BL11B, BL17B1, and BL19U1 beamlines of SSRF for assistance during data collection.

Contributor Information

Yingguo Yang, Email: yangyingguo@sinap.ac.cn.

Wei Huang, Email: iamdirector@fudan.edu.cn.

Tianshi Qin, Email: iamtsqin@njtech.edu.cn.

Data Availability

The data that support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Authors' Contributions

T.Q. conceptualized and designed the experiments. T.Q. and W.H. supervised the work. S.L. synthesized TA-PMA and characterized the materials. F.W., C.C., Y.Y., S.L., Y.L., J.W., and T.M. carried out the device fabrication and characterizations. S.F., L.Y., and Y.Y. carried out the GIWAXS experiment. T.Q. and F.W. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. F.W. participated in data analysis and provided major revisions. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: synthetic routes of TA-PMA. Molecular structures of PMA, TA, and TA-PMA. Figure S2: 1H-NMR of tert-butyl((4′-(bis(4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)methyl)carbamate (1). Figure S3: 1H-NMR of (4′-(bis(4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)methan-aminium bromide (TA-PMA). Figure S4: N-N atom distances of PMA units (~6.302 Å), TA units (~6.401 Å), and MA units (~6.435 Å) calculated by DFT. Figure S5: density of state of TA-PMA and MAPbI3 calculated by DFT. Figure S6: space-charge-limited-current (SCLC) curves of TA-PMA or TA-PMA: PbI2. Figure S7: AFM topography images and RMS surface roughness of 3D (a) and HT2D/3D (b) perovskite films. Figure S8: dark J − V characteristic curves of 3D and HT2D/3D. Figure S9: photovoltaic performances of champion 3D and HT2D/3D PSCs measured under forward and reverse scan direction with scan rate 10 mV s−1. Figure S10: efficiency distribution histograms of 30 independent PSCs based on 3D or HT2D/3D. Figure S11: J − V curves of HT2D/3D-based PSCs using different TA-PMA concentrations. Figure S12: J − V curves of the champion PSCs based on perovskites modified by TA-PMA, phenylmethylammonium (PMA) bromide, and dimethoxy-triarylamine (TA) at the concentration of 3 mg/mL used 3D perovskite as the counterpart. Figure S13: Nyquist plot of (a) pristine 3D and (b) HT2D/3D PSCs at different potential biases from 0 V to 0.5 V and frequency range from 1 to 105 Hz, in the dark. Figure S14: the contact angles of deionized water droplets on the (a) 3D and (b) HT2D/3D perovskite films. Table S1: parameters of the time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopy on the glass. Table S2: photovoltaic performance of the best PSCs based on 3D or HT2D/3D under the 100 mW cm−2 illumination. Table S3: the PV parameters of HT2D/3D-based PSCs in different TA-PMA concentrations. Table S4: the PV parameters of perovskite-modified TA-PMA, PMA, and TA used pristine 3D perovskite as the counterpart, under the 100 mW cm−2 illumination. Table S5: fitted values of different electronic parameters from dark Nyquist plots of 3D and HT2D/3D with voltage from 0 V to 0.5 V. Table S6: PV parameters of HT2D/3D in the stability test.

References

- 1.Lv Y., Zhang H., Wang J., et al. All-in-one deposition to synergistically manipulate perovskite growth for high-performance solar cell. Research. 2020;2020:10. doi: 10.34133/2020/2763409.2763409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tu Y. G., Xu G. N., Yang X. Y., et al. Mixed-cation perovskite solar cells in space. Mechanics & Astronomy. 2019;62(7, article 974221) doi: 10.1007/s11433-019-9356-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng L., Yi C., Tong Y., et al. Halide homogenization for high-performance blue perovskite electroluminescence. Research. 2020;2020, article 9017871:1–10. doi: 10.34133/2020/9017871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren H., Yu S., Chao L., et al. Efficient and stable Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite solar cell with tailored interlayer molecular interaction. Nature Photonics. 2020;14(3):154–163. doi: 10.1038/s41566-019-0572-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang C., Gu H., Xia Y., et al. Two-dimensional Ruddlesden-Popper layered perovskite solar cells based on phase-pure thin films. Nature Energy. 2021;6(1):38–45. doi: 10.1038/s41560-020-00721-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Min H., Kim M., Lee S. U., et al. Efficient, stable solar cells by using inherent bandgap of α-phase formamidinium lead iodide. Science. 2019;366(6466):749–753. doi: 10.1126/science.aay7044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong Q. F., Fang Y. J., Shao Y. C., et al. Electron-hole diffusion lengths > 175 μm in solution-grown CH3NH3PbI3 single crystals. Science. 2015;347(6225):967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.N. R. E. Laboratory. Research-cell Efficiencies. 2020. https://www.nrel.gov/pv/assets/pdfs/best-research-cell-efficiencies.

- 9.Peng W., Miao X. H., Adinolfi V., et al. Engineering of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite crystals by alloying large organic cations for enhanced thermal stability and transport properties. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2016;55(36):10686–10690. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You S., Wang H., Bi S., et al. A biopolymer heparin sodium interlayer anchoring TiO2and MAPbI3Enhances trap passivation and device stability in perovskite solar cells. Advanced Materials. 2018;30(22, article 1706924) doi: 10.1002/adma.201706924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei D., Ma F., Wang R., et al. Ion-migration inhibition by the Cation-π interaction in perovskite materials for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Advanced Materials. 2018;30(31, article 1707583) doi: 10.1002/adma.201707583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavakoli M. M., Tress W., Milic J. V., Kubicki D., Emsley L., Grätzel M. Addition of adamantylammonium iodide to hole transport layers enables highly efficient and electroluminescent perovskite solar cells. Energy & Environmental Science. 2018;11(11):3310–3320. doi: 10.1039/C8EE02404A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H., Wu Y., Shen C., et al. Efficient and stable chemical passivation on perovskite surface via bidentate anchoring. Advanced Energy Materials. 2019;9(13, article 1803573) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201803573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y., Yu S., Sun Y., Liang Z. Phase engineering in quasi-2D Ruddlesden-Popper perovskites. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2018;9(10):2627–2631. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Munir R., Xu Z., et al. Phase transition control for high performance Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite solar cells. Advanced Materials. 2018;30(21, article 1707166) doi: 10.1002/adma.201707166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X., Zhang X., Deng J., et al. Efficient green light-emitting diodes based on quasi-two-dimensional composition and phase engineered perovskite with surface passivation. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):p. 570. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02978-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu W., Wang J., Zuo L., et al. Two-dimensional perovskite solar cells with 14.1% power conversion efficiency and 0.68% external radiative efficiency. ACS Energy Letters. 2018;3(9):2086–2093. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Y., Bai Y., Fang Y., et al. Enhanced thermal stability in perovskite solar cells by assembling 2D/3D stacking structures. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2018;9(3):654–658. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X., Ren X., Liu B., et al. Stable high efficiency two-dimensional perovskite solar cells via cesium doping. Energy & Environmental Science. 2017;10(10):2095–2102. doi: 10.1039/C7EE01145H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang J., Zhang S., Wang N., et al. Enhanced performance of red perovskite light-emitting diodes through the dimensional tailoring of perovskite multiple quantum wells. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2018;9(4):881–886. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b03417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai Y., Xiao S., Hu C., et al. Dimensional Engineering of a graded 3D-2D halide perovskite interface enables UltrahighVocEnhanced stability in the p-i-n photovoltaics. Advanced Energy Materials. 2017;7(20, article 1701038) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201701038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang T., Long M., Qin M., et al. Stable and efficient 3D-2D perovskite-perovskite planar heterojunction solar cell without organic hole transport layer. Joule. 2018;2(12):2706–2721. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan S., Zhou N., Chen Y., et al. Effect of high dipole moment cation on layered 2D organic-inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials. 2019;9(5, article 1803024) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201803024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruggeri E., Anaya M., Galkowski K., et al. Controlling the growth kinetics and optoelectronic properties of 2D/3D lead-tin perovskite heterojunctions. Advanced Materials. 2019;31(51, article 1905247) doi: 10.1002/adma.201905247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z., Lin Q., Chmiel F. P., Sakai N., Herz L. M., Snaith H. J. Efficient ambient-air-stable solar cells with 2D-3D heterostructured butylammonium-caesium-formamidinium lead halide perovskites. Nature Energy. 2017;2(9, article 17135) doi: 10.1038/nenergy.2017.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad S., Fu P., Yu S., et al. Dion-Jacobson phase 2D layered perovskites for solar cells with ultrahigh stability. Joule. 2019;3(3):794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang R., Li R., Cao Y., et al. Oriented quasi-2D perovskites for high performance optoelectronic devices. Advanced Materials. 2018;30(51, article 1804771) doi: 10.1002/adma.201804771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y., Wang F., Cao Y., et al. Benzylamine-treated wide-bandgap perovskite with high thermal-photostability and photovoltaic performance. Advanced Energy Materials. 2017;7(22, article 1701048) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201701048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du K., Tu Q., Zhang X., et al. Two-dimensional lead(II) halide-based hybrid perovskites templated by acene alkylamines: crystal structures, optical properties, and piezoelectricity. Inorganic Chemistry. 2017;56(15):9291–9302. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leguy A. M. A., Azarhoosh P., Alonso M. I., et al. Experimental and theoretical optical properties of methylammonium lead halide perovskites. Nanoscale. 2016;8(12):6317–6327. doi: 10.1039/C5NR05435D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M., Zuo W.-W., Yang Y.-G., et al. Tin halide perovskite films made of highly oriented 2D crystals enable more efficient and stable lead-free perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Letters. 2020;5(6):1923–1929. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.0c00782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong J., Shao S., Kahmann S., et al. Crystal Formation: Mechanism of crystal formation in Ruddlesden-Popper Sn-based perovskites (Adv. Funct. Mater. 24/2020) Advanced Functional Materials. 2020;30(24, article 2070154) doi: 10.1002/adfm.202070154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nenon D. P., Christians J. A., Wheeler L. M., et al. Structural and chemical evolution of methylammonium lead halide perovskites during thermal processing from solution. Energy & Environmental Science. 2016;9(6):2072–2082. doi: 10.1039/C6EE01047D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin C., Lu J., Xu Y., et al. Low-CostN,N′-Bicarbazole-Based dopant-free hole-transporting materials for large-area perovskite solar cells. Advanced Energy Materials. 2018;8(21, article 1800538) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201800538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W., Pathak S., Sakai N., et al. Enhanced optoelectronic quality of perovskite thin films with hypophosphorous acid for planar heterojunction solar cells. Nature Communications. 2015;6(1, article 10030) doi: 10.1038/ncomms10030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng L., Sun C., Wang R., et al. Tailored phase conversion under conjugated polymer enables thermally stable perovskite solar cells with efficiency exceeding 21% Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2018;140(49):17255–17262. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo D., Yang W., Wang Z., et al. Enhanced photovoltage for inverted planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Science. 2018;360(6396):1442–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Euvrard J., Gunawan O., Mitzi D. B. Impact of PbI2Passivation and grain size engineering in CH3NH3PbI3Solar absorbers as revealed by carrier-resolved photo-Hall technique. Advanced Energy Materials. 2019;9(47, article 1902706) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201902706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yun Y., Wang F., Huang H., et al. A nontoxic bifunctional (anti)solvent as digestive-ripening agent for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Advanced Materials. 2020;32(14, article 1907123) doi: 10.1002/adma.201907123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun C., Guo Y., Fang B., et al. Facile preparation of high-quality perovskites for efficient solar cells via a fast conversion of wet PbI2 precursor films. RSC Advances. 2017;7(36):22492–22500. doi: 10.1039/C7RA03066E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Q., Ma T., Wang F., et al. Rapid microwave-annealing process of hybrid perovskites to eliminate miscellaneous phase for high performance photovoltaics. Advanced Science. 2020;7(12, article 2000480) doi: 10.1002/advs.202000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X., Wang Y., Zhang T., Liu X., Zhao Y. Steric mixed-cation 2D perovskite as a methylammonium locker to stabilize MAPbI3. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2020;59(4):1469–1473. doi: 10.1002/anie.201911518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L., Zhou H., Hu J., et al. A Eu3+-Eu2+ ion redox shuttle imparts operational durability to Pb-I perovskite solar cells. Science. 2019;363(6424):265–270. doi: 10.1126/science.aau5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y., Akin S., Pan L., et al. Ultrahydrophobic 3D/2D fluoroarene bilayer-based water-resistant perovskite solar cells with efficiencies exceeding 22% Science Advances. 2019;5(6, article 2543) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw2543.eaaw2543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bi S., Leng X., Li Y., et al. Interfacial modification in organic and perovskite solar cells. Advanced Materials. 2019;31(45, article 1805708) doi: 10.1002/adma.201805708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Igbari F., Li M., Hu Y., Wang Z.-K., Liao L.-S. A room-temperature CuAlO2hole interfacial layer for efficient and stable planar perovskite solar cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2016;4(4):1326–1335. doi: 10.1039/C5TA07957H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y., Luo J., Wei A., Liu J., Zhao Y., Xiao Z. Study of perovskite solar cells based on mixed-organic-cation FAxMA1−xPbI3 absorption layer. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2019;21(22):11822–11828. doi: 10.1039/C9CP02003A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: synthetic routes of TA-PMA. Molecular structures of PMA, TA, and TA-PMA. Figure S2: 1H-NMR of tert-butyl((4′-(bis(4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)methyl)carbamate (1). Figure S3: 1H-NMR of (4′-(bis(4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)methan-aminium bromide (TA-PMA). Figure S4: N-N atom distances of PMA units (~6.302 Å), TA units (~6.401 Å), and MA units (~6.435 Å) calculated by DFT. Figure S5: density of state of TA-PMA and MAPbI3 calculated by DFT. Figure S6: space-charge-limited-current (SCLC) curves of TA-PMA or TA-PMA: PbI2. Figure S7: AFM topography images and RMS surface roughness of 3D (a) and HT2D/3D (b) perovskite films. Figure S8: dark J − V characteristic curves of 3D and HT2D/3D. Figure S9: photovoltaic performances of champion 3D and HT2D/3D PSCs measured under forward and reverse scan direction with scan rate 10 mV s−1. Figure S10: efficiency distribution histograms of 30 independent PSCs based on 3D or HT2D/3D. Figure S11: J − V curves of HT2D/3D-based PSCs using different TA-PMA concentrations. Figure S12: J − V curves of the champion PSCs based on perovskites modified by TA-PMA, phenylmethylammonium (PMA) bromide, and dimethoxy-triarylamine (TA) at the concentration of 3 mg/mL used 3D perovskite as the counterpart. Figure S13: Nyquist plot of (a) pristine 3D and (b) HT2D/3D PSCs at different potential biases from 0 V to 0.5 V and frequency range from 1 to 105 Hz, in the dark. Figure S14: the contact angles of deionized water droplets on the (a) 3D and (b) HT2D/3D perovskite films. Table S1: parameters of the time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopy on the glass. Table S2: photovoltaic performance of the best PSCs based on 3D or HT2D/3D under the 100 mW cm−2 illumination. Table S3: the PV parameters of HT2D/3D-based PSCs in different TA-PMA concentrations. Table S4: the PV parameters of perovskite-modified TA-PMA, PMA, and TA used pristine 3D perovskite as the counterpart, under the 100 mW cm−2 illumination. Table S5: fitted values of different electronic parameters from dark Nyquist plots of 3D and HT2D/3D with voltage from 0 V to 0.5 V. Table S6: PV parameters of HT2D/3D in the stability test.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.