OA is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions, affecting millions of people worldwide and placing a huge burden on healthcare systems [1]. Not only is OA a major reason for joint surgery, it is also a serious disease, as people with OA suffer from chronic pain, impaired function and increased risk of comorbidities [2]. Recent developments in OA clinical trials have shown clinically significant progress in drug development for the first time in many years, with agents targeting structure and pain modification. Structural damage and its modulation to improve patient symptoms have been the ‘holy grail’ in OA research for some time. There is currently a strong pipeline of new pharmacological therapies for the modulation of structural damage/cartilage repair, with compounds in Phase 2/3 clinical trials, including wnt pathway inhibitors such as lorecivivint, ADAMTS-5 inhibitors, bisphosphonates including zoledronic acid, cathepsin K inhibitors and sprifermin, a recombinant human fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF-18), and agonist of FGFR2/3. Naturally derived products curcumin and boswellia are also being tested, but trials have been inconclusive (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online).

These would appear to be exciting times for OA pharmacology. However, mixed results from structure modification trials have led some researchers to consider pain as a more clinically important treatment target. After all, pain is often the main symptom, leading to significant impact on quality of life [3], and is what drives most people with OA to seek medical help [4]. Recently, significant advances have been made in the neurobiology of pain in OA, with recognition that pain sensitization is an important feature [5].

New compounds specifically targeting pain in OA, including neutralizing antibodies to nerve growth factor (NGF) and centrally acting analgesics are in advanced stages of regulatory approval and may be even closer to the clinic than structural modifiers. Monoclonal neutralizing antibodies to NGF such as tanezumab and fasinumab have been effective in pain management for large joint OA in Phase 2/3 trials [6, 7]. Other compounds include intra-articular capsaicin, previously available only in topical form [8]. There is also increasing recognition that pain sensitization can be targeted with centrally acting agents such as duloxetine [9].

So where does this leave us in the management of OA? Stratification tools can be developed to aid in the assessment and management of OA [10]. Enriching patient subgroups by stratification in clinical trials – for example in post-traumatic, synovitis and pain sensitization – may yield more useful results for patients who could benefit from personalized strategies. Such interventions may require one or more drug interventions. Further, combining pharmacotherapy with exercise and physical therapy is proven to reduce pain and improve function in knee and hip OA, with improved performance, reduced disability and improved quality of life [11].

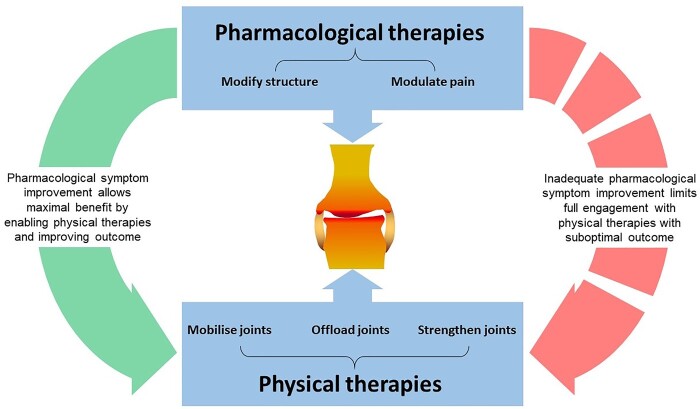

Proposing combination interventions is an attractive strategy for OA (Fig. 1). This combination therapy model relies on the efficacy of all the components for the outcome; critically, that pharmacological symptom improvement should allow people to gain maximal benefit by enabling physical therapies and improve outcome. Novel trial design remains challenging in OA and is crucial in testing such complex interventions, but also in assessing meaningful outcomes, and effect size, where changes may only occur over several years.

Fig. 1.

Effective therapies for OA are likely to involve a combination of therapies modifying joint structures and modulating pain symptoms

Pain can affect motivation to engage with other interventions like physical therapies that include exercise, joint bracing and splinting; effective pharmacological therapies should promote a more holistic approach to managing OA.

So, does the time cometh for new OA treatments? Proposed labels in OA for tanezumab and fasinumab have been submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA and are also under current review by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK. If this new class of drugs is licensed for use in people with large joint OA of the hip and knee, then their approval is likely to lead to a step change in OA management. The opportunities and challenges that a new biologic therapeutic agent such as anti-NGF monoclonal antibodies poses are worthy of some consideration by the rheumatology community. The promise of anti-NGF monoclonal antibodies as a new therapeutic option may prove desirable for some people with OA, particularly those who have failed to respond to first-line treatments and who have an inadequate response (or cannot take) other pharmacological analgesia. With reportedly at least equivalent analgesic efficacy, anti-NGF monoclonal antibodies offer an alternative therapeutic option, without some of the prohibitive side effects and risks associated with NSAIDs and opiates. However, early trials of this therapeutic class were halted due to cases of rapidly progressive OA (RPOA); although this was in part found to correlate with higher doses and the co-prescription of NSAIDs, even with mitigation, this remains a consideration for this drug class. Careful post-marketing surveillance, including the reporting of potential adverse events such as RPOA will be needed. The drug’s impact on other care pathways (negative or positive) will also need monitoring. A careful review of what is needed for adequate service provision to allow the safe prescribing and monitoring of these novel treatments will need addressing, both locally and nationally in the light of NICE guidance. We propose that real-world data for these drugs in the form of registries, such as has occurred in British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) will likely be necessary for any biologics in OA, to allow us to assess fully their longer-term benefits and harms. Who will deliver this? Rheumatology, with its experience in biologic therapies looks likely to be the critical overseer of any newly licensed drug classes and should ready itself for this step change.

We need to acknowledge the challenges that the provision of new therapeutics for a new indication, including biologics, will inevitably place on healthcare services in the UK, particularly at this time. Currently, rheumatology services in the UK see a very low number of patients with OA. In many regions, OA referrals are indeed triaged to First Contact Practitioners and Musculoskeletal Interface Clinical Assessment Services (MICAS), bypassing rheumatology altogether. If biologics are licensed by regulators, assessment of eligibility for these new agents will likely come to rheumatology services. Given our experience in using and monitoring monoclonal antibody therapies, this would seem entirely appropriate. However, we must highlight that the instigation of any new therapeutic for OA is likely to require enhanced funding and pathway refinement, in tandem with an improved interaction between primary care, intermediate care/triage services, orthopaedics, rheumatology and radiology services, to enable optimal patient care.

There is an air of cautious optimism around the potential for new OA therapies; opportunity is always balanced with potential risk and the need for change. Approval of new agents for clinical use such as anti-NGF monoclonal antibodies provides new hope for many living with OA. For clinicians treating OA, we should look to harness these developments to optimise our care of OA, working across disciplines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

F.E.W is a UKRI Future Leaders Fellow (S016538) and a member of the Centre for Osteoarthritis Pathogenesis Versus Arthritis (grants 20205 and 21621). She is supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Funding: No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: N.S. has been a consultant for or has received clinical study grants and honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Servier and Pfizer. F.E.W. has been a coordinating investigator for Astellas and received clinical study grant and honoraria from Pfizer, relating to therapeutics described in this manuscript. A.L.T. has been a consultant for or received honoraria from Abbvie, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D. et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. March LC, Lo M, Arden C, Gates N, Leyland L, Hawker K, King GL. OARSI white paper- OA as a serious disease: Osteoarthritis Research Society International. https://oarsi.org/education/oarsi-resources/oarsi-white-paper-oa-serious-disease (22 February 2021, date last accessed).

- 3. Hawker GA, Stewart L, French MR. et al. Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis–an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1145–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neogi T, Frey-Law L, Scholz J. et al. Sensitivity and sensitisation in relation to pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: trait or state? Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:682–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fan ZR, Ma JX, Wang Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of tanezumab administered as a fixed dosing regimen in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled phase III trials. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:2155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schnitzer TJ, Easton R, Pang S. et al. Effect of tanezumab on joint pain, physical function, and patient global assessment of osteoarthritis among patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 2019;322:37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stevens RM, Ervin J, Nezzer J. et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intra-articular transcapsaicin for pain associated with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1524–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chappell AS, Desaiah D, Liu-Sefert H. et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract 2011;11:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sandhar S, Smith TO, Toor K, Howe F, Sofat N.. Risk factors for pain and functional impairment in people with knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020;10:e038720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goh SL, Persson MSM, Stocks J. et al. Efficacy and potential determinants of exercise therapy in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Phys Rehabil Med 2019;62:356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). All data relevant to the study are included in the article.