Abstract

Background Thumb carpometacarpal joint (CMCJ) osteoarthritis is common and can lead to significant morbidity making it a condition frequently treated by hand surgeons when initial conservative measures fail. The surrounding ligamentous structures are complex and important to maintain thumb CMCJ stability.

Objectives The aim of this study was to review the normal and arthritic anatomy of the thumb CMCJ, focusing on morphology and position of osteophytes and the gap between metacarpal bases, and the effect of these on intermetacarpal ligament integrity. This may be the sole ligament suspending the first metacarpal following trapeziectomy and could determine the need for further stabilization during surgery, avoiding potential future failures.

Methods Computed tomography (CT) scans of a normal cohort and those with arthritic changes who had undergone trapeziectomy following the scan were identified. The three-dimensional reconstructions were examined for osteophyte position on the saddle and the intermetacarpal distance.

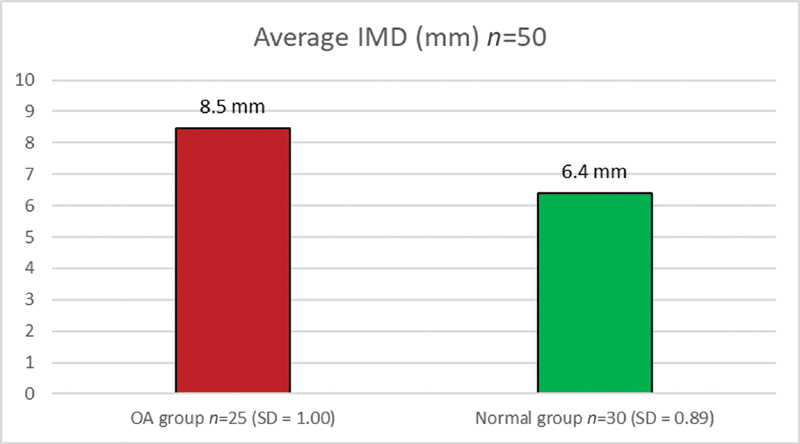

Results A total of 55 patients, 30 normal and 25 arthritic, were identified and studied. The most common anatomic position for osteophytes was the intermetacarpal ulnar aspect of the trapezium. The intermetacarpal distance increased by an average of 2.1 mm in the presence of the arthritic process.

Conclusions The findings point to an increase in the intermetacarpal distance, and hence lengthening of the ligament with potential damage, possibly secondary to osteophyte formation and wear. Further prospective research is required to determine whether using preoperative CT scanning to define osteophyte position and measure the intermetacarpal distance would predict probable damage to the ligament, hence providing an indication for stabilization and reconstruction in trapeziectomy surgery.

Level of Evidence This is a Level III, retrospective cohort study.

Keywords: thumb carpometacarpal joint, CMCJ arthritis, osteophyte, trapeziectomy, intermetacarpal ligament

Osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint (CMCJ) of the thumb is common and diagnosis is based on symptoms of localized pain and tenderness, instability on examination, and radiographic evaluation. Prevalence differs depending on which diagnostic method is employed. 1 Radiologically, prevalence is demonstrated in 7 to 15% of an adult population, 2 reaching up to 65% in postmenopausal females. 3 Symptomatic prevalence is lower, with figures in the literature of around 5% in elderly women. 4 Symptomatic thumb CMCJ osteoarthritis leads to pain and functional morbidity, owing to lower pinch and grip strength. 5 These debilitating symptoms account for significant presentation rates to primary care, and ultimately make it one of the commonest conditions treated by hand surgeons when initial conservative measures fail. 1

Treatment of symptomatic thumb CMCJ osteoarthritis starts with nonoperative measures such as hand therapy to strengthen thenar muscles, splinting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and corticosteroid injection. If these measures are unsuccessful, surgical treatment is sought; however, the type of surgical procedure is debatable, likely due to the heterogenous nature of the condition. 1 6 The operative procedure employed is therefore based not only upon the extent of the arthritic changes, generally staged radiographically using the widely used modified Eaton classification system, 7 8 as well as taking account of the patient's functional demand. In early stage disease, several techniques aimed at preserving the trapezium, therefore reducing the risk of metacarpal collapse, exist. These include arthroscopic procedures such as debridement, synovectomy, and electrothermal shrinkage of ligaments to augment stability, as well as first metacarpal (1st MC) extension osteotomy to offload forces on the attenuated volar articular surface. 9

Trapeziectomy (complete or partial) has long been advocated as a successful treatment in later stages of disease; however, there is controversy regarding the need for, and options available, regarding ligament reconstruction and stabilization. Following complete trapeziectomy, the only remnant ligaments suspending the 1st MC are probably the intermetacarpal ligaments (IMLs). 10 As later discussed, these ligaments are known to have a variable attachment pattern and shape, and in cases where this ligament is deficient either congenitally, or from wear on a prominent trapezial osteophyte in the first web space, then ligament reconstruction may be needed to prevent subluxation or collapse of the 1st MC. 11

Saltzherr et al 12 noted a higher interobserver reliability and detection rate for thumb CMCJ and scaphotrapezium joint osteoarthritis on computed tomography (CT) imaging compared with radiography. The authors suggested that using CT images helped fully appreciate the osteoarthritic morphological changes, especially of the scaphotrapezium joint, which may have been missed on standard radiographs. Fully appreciating the pathological morphology may influence choice of surgery.

The aim of this study was to review the normal and pathological anatomy of the thumb CMCJ, focusing on osteophyte size, morphology and position, and the gap between the metacarpal bases; and the possible effect of these on the IML. Understanding these anatomical features may advocate the routine analysis of a preoperative CT scan to help predict the need and likely benefit for extra reconstructive surgery alongside trapeziectomy.

Methods

This was a single-center, retrospective, CT-based anatomic study. Two lists of patients were obtained. The first list was for patients who had sustained a scaphoid fracture. These were assumed to have a “normal” CMCJ condition prior to the injury and it would therefore be safe to adopt that they would denote the anatomic control group. This was further corroborated by examining the imaging and reports as well. As an added measure, the cutoff age for inclusion in this group was 35 years or younger. This was to reduce the potential risk of early or subclinical arthritic change in this cohort. The second list obtained was for patients who had undergone trapeziectomy. This represented the pathological cohort. At our center, most patients undergoing trapeziectomy have a preoperative CT scan to assess the pathoanatomy.

Data collection and measurements were done solely by the first author. This was to reduce the chance of interobserver error. In the pathological group, for each patient, the electronic notes record was reached for the operation note. This was to confirm the diagnosis and trapeziectomy as the code procedure. This was also to demonstrate that this cohort of patients had end-stage arthritic disease necessitating surgical intervention in the form of trapezium excision.

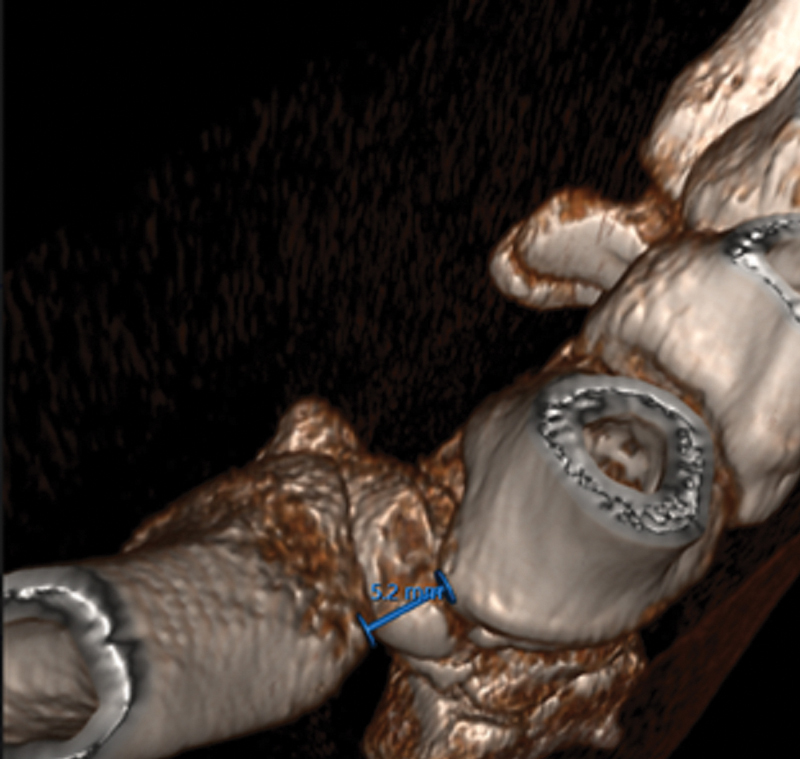

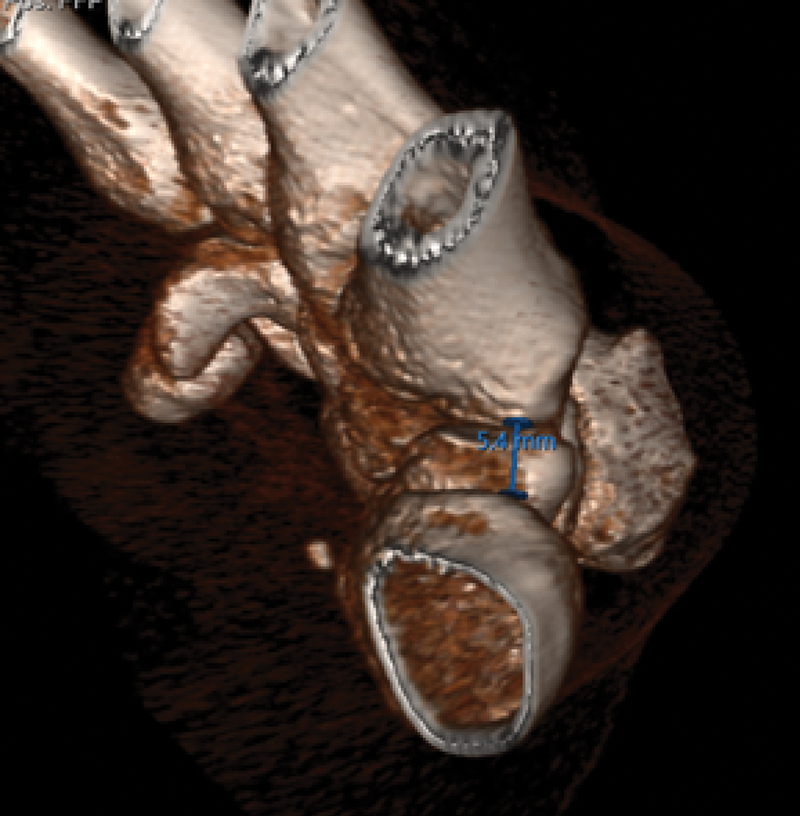

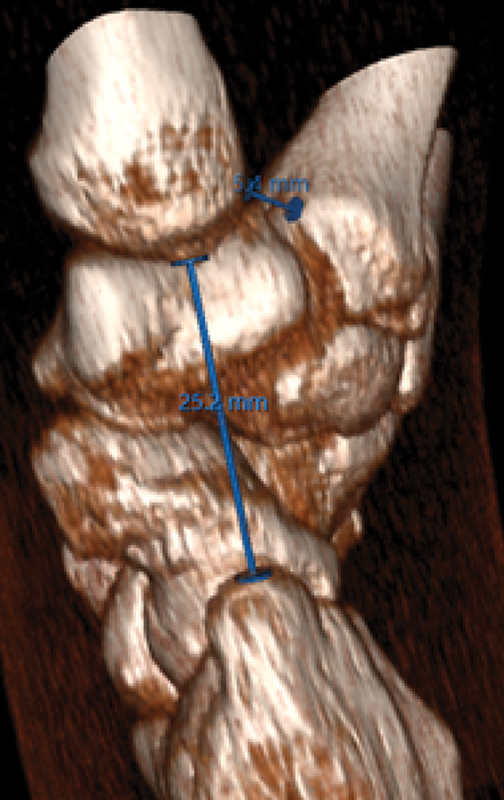

The radiology system (SECTRA AB) was then used to access the CT scans. All wrist CT scans were performed in the neutral, posteroanterior (PA) position, as per the departmental protocol. The images were three-dimensionally (3D) reconstructed and used to obtain the measurements. The primary measures were the intermetacarpal distance (IMD); a distance in mm between the base of the 1st MC and 2nd MC, and the morphology and location of the osteophytes on the saddle thumb CMCJ. The secondary measure was the distance between the 1st MC and the radial styloid (RSD).

In collaboration with the senior author, two points were agreed as coordinates to be used for measurement. For the IMD, the first is on the dorsoulnar 1st MC ridge, at the junction of articular surface and start of the base of the shaft. The second point is on the most radial ridge of the 2nd MC, at the junction of base and shaft flaring. An osteophyte was defined as any bony outgrowth between the bone and its articular surface. 13 The osteophyte position on the saddle thumb CMCJ was divided into six locations, either ulnar (U) or radial (R), and subdivided into volar, intermediate (IM), and dorsal. For the RSD, again two points were marked on the 3D CT; the most inferior tip of the 1st MC and the most superior point of the radial styloid (RS). For both measurements, the points were first marked on the “PA” 3D view but subsequently adjusted while checking all around the 3D reconstruction image ensuring most accurate placement ( Figs. 1 2 3 4 5 ). The same process was strictly followed for each specimen and performed by the first author. The null hypothesis was that the average IMD would be equal for both the arthritic and normal cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Posteroanterior view reconstructed three-dimensional computed tomography showing the two points and distance (intermetacarpal distance) measured.

Fig. 2.

Top-down view reconstructed three-dimensional computed tomography showing the two points and distance (intermetacarpal distance) measured.

Fig. 3.

End-on view reconstructed three-dimensional computed tomography showing the two points and distance (intermetacarpal distance) measured.

Fig. 4.

Posteroanterior view reconstructed three-dimensional computed tomography showing the two points and distance (radial styloid) measured.

Fig. 5.

Lateral view reconstructed three-dimensional computed tomography showing the two points and distance (radial styloid) measured.

Results

A total of 55 CT scans were included in the study; 30 in the normal group and 25 in the arthritic group. The average age in the normal group was 25 years, 93.3% being male. The average age in the arthritic group was 60 years, 92% female. This gender distribution somewhat reflects the gender differences seen in prevalence of scaphoid fractures and CMCJ arthritis respectively. 1 14 The CT scans confirmed, as per the Modified Eaton radiographic classification system, 8 that the normal (control) group had no radiographic evidence of CMCJ arthritis, including no osteophytes and therefore, did not meet the criteria for staging. All 25 patients in the arthritic group had osteophytes present on CT imaging, indicating grade 2 CMCJ arthritis or above.

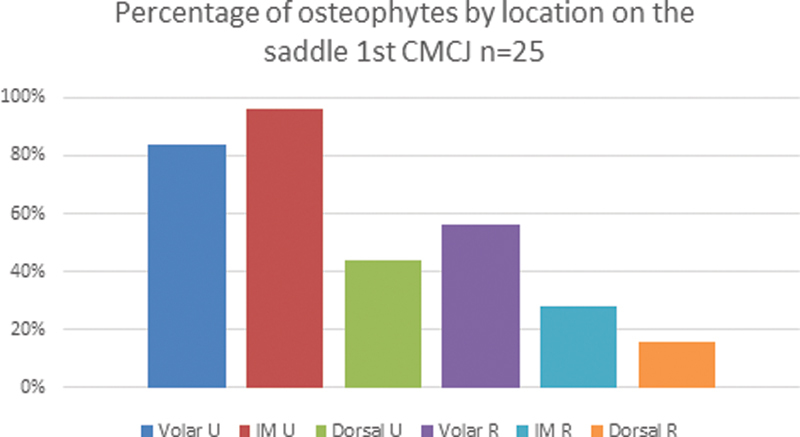

The average IMD in the arthritic group was 8.5mm (SD = 1.00). The average IMD in the control group was 6.4 mm (SD = 0.89) (see Fig. 6 ). Results were compared using an unpaired, 2-tailed t -test. Statistical significance was defined as a p -value <0.05. This data demonstrated a statistically significant difference ( p = 1.67 × 10 −10 ) between the IMD of the arthritic and normal cohorts, therefore the null hypothesis was rejected suggesting an average increase in IMD of 2.1 mm (95% confidence interval: 1.56–2.60 mm) associated with the arthritic process. The most common anatomic position for osteophytes was the intermediate ulnar aspect of the trapezium; the site of the IML. This was present in 96% of the arthritic cohort (see Fig. 7 ) . There was no difference in the RSD between the two groups, both with approximate averages of 25 mm.

Fig. 6.

Average intermetacarpal distance (IMD) in both cohorts. SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 7.

Osteophyte location in the pathological group. CMCJ, carpometacarpal joint; IM, intermetacarpal.

Discussion

The thumb CMCJ is one of the few saddle joints in the human skeleton and facilitates biaxial movements in the sagittal and coronal planes, with combinations of both allowing for more complex movements such as thumb opposition and pinch grip, while preventing axial rotation. It is formed in a “biconcavoconvex” manner, by the articulated surfaces of the base of the 1st MC and the distal surface of the trapezium, as two, reciprocally interlocking saddle shapes that oppose each other. This incongruous osseous anatomy is innately unstable in the resting position; therefore, the stability of the joint is reliant upon its associated ligamentous structures, as well as 9 muscles, which provide dynamic stabilization. 1 15

The ligamentous complex of the thumb CMCJ is complex. There remain inconsistencies in the literature about the number, figures between three and seven are cited, and the functional importance of each one. Commonly described ligaments are the anterior oblique (“beak/palmar”) ligament (AOL), the dorsoradial ligament, and the volar and dorsal IMLs. 11 The dorsoradial ligament is the strongest and thickest of the structures, primarily stabilizing both dorsal and radial translation of the 1st MC on the trapezium. Due to the intracapsular location of the AOL, its role is as a static stabilizer and it is often considered to be the most important stabilizing ligament of the joint, not only resisting dorsoradial subluxation but also restraining abduction, extension and pronation forces. The IMLs attach from the radial base of the 2nd MC to the ulnar aspect of the base of the 1st MC and restrict radial translation of the base of the 1st MC. The anatomical description of this ligament is variable, one study described it as “Y” shaped, with two attachments on the 1st MC, another found only single attachments on the 1st MC, and another found the “Y” pattern in 2 out of 10 of their specimens. 11

The etiology of thumb CMCJ osteoarthritis is multifactorial but is broadly divided into primary and secondary (posttraumatic) causes. Primary causes include ligamentous hypermobility, ligament laxity, hormonal and biochemical influences, and anatomical differences in the geometry of the trapezium 1 —all of which affect joint biomechanics. The relative incongruity of the thumb CMCJ makes it prone to high cartilage stress, a factor associated with an increased risk of osteoarthritis. 16 Similarly, previous intra-articular fracture, for example, Bennett's fracture, or ligamentous injury, especially of AOL, can accelerate arthritic progression. 1 Laxity of the AOL, which allows dorsoradial subluxation of the 1st MC on the trapezium, is thought to be the main contributor to the pathological process, facilitating the attenuation of the articular cartilage, joint space narrowing, and formation of osteophytes. 17

To date, in our knowledge, no formalized method of measuring the IMD has been published in the literature, and no study has specifically looked at the morphology of the osteophytes in the process of thumb CMCJ osteoarthritis. The hypothesis was that osteophyte formation between the 1st and 2nd MC bases would stretch or damage the IML and in turn result in an increased IMD. Our findings support this hypothesis in that the most common osteophyte location is between the two metacarpal bases, where the IML is situated, and that the arthritic process leads to an increase IMD, possibly signifying disruption of the IML. This distance could potentially be used as a marker to determine the stability of 1st MC post trapeziectomy, and hence the likelihood of requiring an additional procedure, such as ligament reconstruction tendon interposition, tightrope stabilization, or using an anchor, to prevent subsequent collapse post trapeziectomy. A limitation to our study was the small sample size and therefore the inability to perform meaningful subgroup analysis on variables such as gender and height which affect bone size.

Trapezium excision alone can be, and most of the time is, a very successful and rewarding procedure in alleviating pain and restoring thumb function for the patient. However, there is still a high proportion of “failed” trapeziectomies, mostly complicated by collapse and therefore persisting symptoms. Secondary stabilizing procedures reduce this risk but present their own potential problems and add to surgical time. It would therefore be very helpful from the surgical viewpoint and from the patients' perspective, to try and predict which patients may have a problematic IML and therefore may as a result be unstable and collapse, thus, benefitting from further stabilizing procedures.

In our study, the findings support our hypothesis that the most common osteophyte location is between the two MC bases, where the IML is situated. This is further supported by the increase in IMD. There does not appear to be a discernible loss of height in the arthritic process when measuring between the 1st MC base and the radial styloid. However, if this is present as a baseline in the patient's imaging, any future postoperative problems leading to further CT imaging can be used for comparison in measuring degree of 1st MC collapse, and may help in guiding further management.

Further prospective studies are required to ascertain whether through preoperative CT scan planning, to determine osteophyte position and measure IMD, hence predict damage to the IML, would give an indication for the need for stabilization and reconstruction following trapeziectomy. However, other factors such as the overall state of the soft tissue, capsule, and bony architecture might come in to play further confounding the matter.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Ethical Approval

The study did not require ethical approval.

References

- 1.Van Heest A E, Kallemeier P. Thumb carpal metacarpal arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(03):140–151. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haara M M, Heliövaara M, Kröger H. Osteoarthritis in the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Prevalence and associations with disability and mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(07):1452–1457. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahaghin S, Bierma-Zeinstra S MA, Ginai A Z, Pols H AP, Hazes J MW, Koes B W. Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study) Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(05):682–687. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.023564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niu J, Zhang Y, LaValley M, Chaisson C E, Aliabadi P, Felson D T. Symmetry and clustering of symptomatic hand osteoarthritis in elderly men and women: the Framingham Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42(02):343–348. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreiber J J, McQuillan T J, Halilaj E. Changes in local bone density in early thumb carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(01):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Nortwick S, Berger A, Cheng R, Lee J, Ladd A L. Trapezial topography in thumb carpometacarpal arthritis. J Wrist Surg. 2013;2(03):263–270. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1350088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton R G, Littler J W. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(08):1655–1666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton R G, Glickel S Z. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 1987;3(04):455–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melville D M, Taljanovic M S, Scalcione L R. Imaging and management of thumb carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(02):165–177. doi: 10.1007/s00256-014-1997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon J. Partial trapeziectomy and interpositional arthroplasty for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis of the thumb. J Hand Surg [Br] 1995;20(05):700–706. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(05)80140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanno M, Buford W LJ, Jr, Patterson R M, Andersen C R, Viegas S F. Three-dimensional analysis of the ligamentous attachments of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(07):1160–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saltzherr M S, van Neck J W, Muradin G SR. Computed tomography for the detection of thumb base osteoarthritis: comparison with digital radiography. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(05):715–721. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Kraan P M, van den Berg W B. Osteophytes: relevance and biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(03):237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler J R, Hughes T B. Scaphoid fractures. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34(01):37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmunds J O. Current concepts of the anatomy of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(01):170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halilaj E, Moore D C, Laidlaw D H. The morphology of the thumb carpometacarpal joint does not differ between men and women, but changes with aging and early osteoarthritis. J Biomech. 2014;47(11):2709–2714. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khorashadi L, Ha A S, Chew F S. Radiologic guide to surgical treatment of first carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(05):1152–1160. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]