Abstract

Decreased sound tolerance (DST) is a negative reaction to environmental sounds and is estimated to affect 3.5% of the population. This case report presents the evaluation and management of an adult female with severe, longstanding misophonia. Her evaluation included comprehensive audiometric testing (including uncomfortable loudness levels) and a detailed assessment of the impact of DST on her life. She enrolled in tinnitus retraining therapy and began receiving treatment aiming to facilitate habituation of bothersome environmental sounds. This case was complicated by the advent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and a telemedicine hybrid approach was employed to increase access to audiologic care. Using this structure, some appointments occurred in person in the clinic and others occurred via a telemedicine video visit format. Telemedicine video visits facilitated in-depth discussions, afforded the opportunity to answer questions, and provided the option of cloud-based remote programming of on-ear devices. Future care will continue to employ a hybrid approach.

Keywords: misophonia, decreased sound tolerance, hybrid telemedicine, tinnitus retraining therapy

Decreased sound tolerance (DST) is a term used to describe negative reactions to sound that are not experienced by an average listener. 1 Although exact prevalence data are unknown, an estimated 3.5% of the general population experience DST. 2 Individuals who experience DST may experience reactions to the physical characteristics of sound (hyperacusis), reactions to specific patterns of sound or sounds occurring in specific contexts (misophonia), or a combination of both. 3 These reactions may include emotional components (e.g., fear, annoyance) and physical manifestations (e.g., pain, panic) 2 that can significantly impact a person's quality of life. 4 5 6

There is not a consensus related to the recommended process of evaluating and treating DST. Many agree that an evaluation should include audiometric data (including uncomfortable loudness level [ULL] measurements), self-report questionnaire data, and a detailed interview. 3 7 Although the triggering sounds themselves and the contexts in which they present will differ, the negative reactions that occur as a result of exposure to triggering sounds for someone suffering from hyperacusis and another person suffering from misophonia may be identical. 3 Distinguishing between them can be difficult, as patients with hyperacusis, misophonia, or a combination may all present with reduced ULLs. 3 In these cases, the information obtained during the interview portion of the evaluation can help identify specific sounds that are problematic. 3 Many individuals with hyperacusis react negatively to loud sounds (or sounds perceived as loud to them) regardless of the context, while an individual with misophonia would be more apt to react to sounds with particular meaning in specific contexts (e.g., eating sounds, sniffling, lip smacking), even if the sounds are not particularly loud. 3

Aazh et al 7 discussed that the diagnosis of hyperacusis is difficult to make based solely on ULLs, as the average ULLs reported across studies for individuals with hyperacusis range quite widely. 8 9 10 A recommendation has been proposed to make the diagnosis of hyperacusis consistent: ULL min (average ULL at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 kHz for the ear with the lower average ULL) ≤77 dB hearing level (HL) and a score of ≥22 on the hyperacusis questionnaire (HQ). 11 In addition to audiometric testing, there are several available questionnaires focusing on the impact of hyperacusis on a person's life. 12 13 14 15

To diagnose misophonia, Schröder et al 16 proposed six criteria focusing on the reactions that an individual may have to specific sounds in specific contexts. Dozier et al 17 expanded these criteria to include more detail about the triggering stimulus and specific responses that are generated. Multiple questionnaires have been developed to evaluate the effects of misophonic responses on a sufferer's life. 16 18 19 20

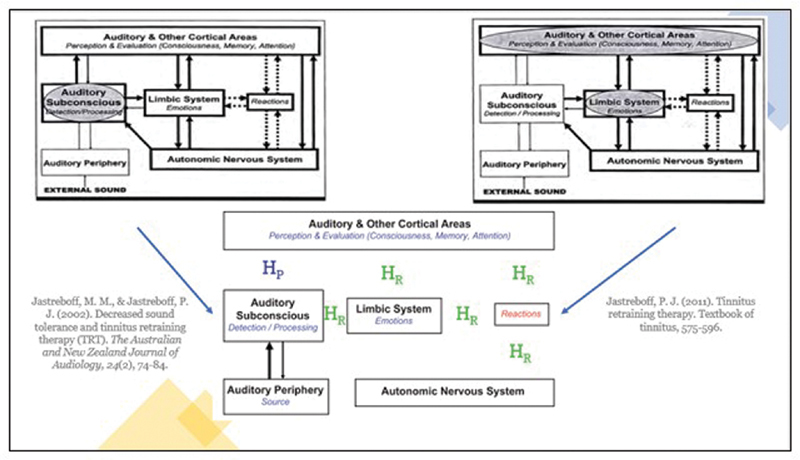

Many treatments have been proposed for hyperacusis and misophonia. Pienkowski et al reviewed several treatment options for hyperacusis, including counseling, hyperacusis activities treatment, social support, cognitive behavioral therapy, sound therapy, hearing protection, and medications. 21 Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) has also been used to treat DST. 1 3 22 23 TRT is an intervention developed from the Jastreboff neurophysiological model of tinnitus, which proposes that interactions between the auditory, limbic, and autonomic nervous system are responsible for the reactions generated by bothersome tinnitus. 24 The TRT protocol involves a combination of directive counseling (to reduce the strength of negative reactions related to bothersome tinnitus) and sound therapy (to reduce the perceived strength of the tinnitus signal). 25 Ultimately, the goal of TRT is to reduce the impact of tinnitus on a patient's life. 25 Given the overlap in neuronal networks involved in the development of bothersome tinnitus and DST, Jastreboff and Jastreboff developed modified versions of this treatment approach which specifically target hyperacusis and misophonia. The goal of this approach is to reduce the impact of bothersome environmental sounds. 1 3 26 The application of the TRT protocol as a treatment approach for DST boasts success rates around 80%. 3 23

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a shift toward telehealth when possible across the healthcare spectrum. 27 This introduced a new set of challenges to the process of evaluation and treating tinnitus and DST. In the field of otorhinolaryngology, it has recently been estimated that more than 50% of appointments could be performed via telemedicine. 28 Although some limitations have been identified, 29 other evidence suggests treatment of tinnitus can be successful via telehealth. 30 31 32 Data specific to the implementation of management of DST via telehealth are limited. Additionally, although a hybrid telemedicine approach (a combination of in-person care and remote interactions) has been used in various clinical settings, 33 34 35 there are limited data related to using this approach for tinnitus and DST.

This case report features a 23-year-old adult female, given the pseudonym of Allison, who suffered from longstanding DST before seeking evaluation and treatment. The details of Allison's case will include the relevant history, evaluation of DST, and treatment with TRT using a hybrid telehealth model during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Case Presentation

Allison, a 23-year-old woman with an unremarkable prior medical history aside from a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder (ADD), was first evaluated in the Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) Clinic for DST and intermittent tinnitus. She had recently moved to the area and was beginning a new engineering job at a startup company. On the day of the ENT appointment, she described her primary issue as hypersensitivity to certain sounds, with tinnitus present as a secondary complaint. More specific information about triggering sounds was not obtained at this visit, although she did indicate that her sensitivity to sounds caused her to feel anxious. She reported that she had experienced tinnitus for approximately 1 year. The tinnitus was described as a bilateral sound with multiple components that she described as buzzing, hissing, and ringing. She noted that the tinnitus was more noticeable in quiet and that white noise helped to alleviate it. She denied hearing loss and indicated that she had never been evaluated for ear-related problems before.

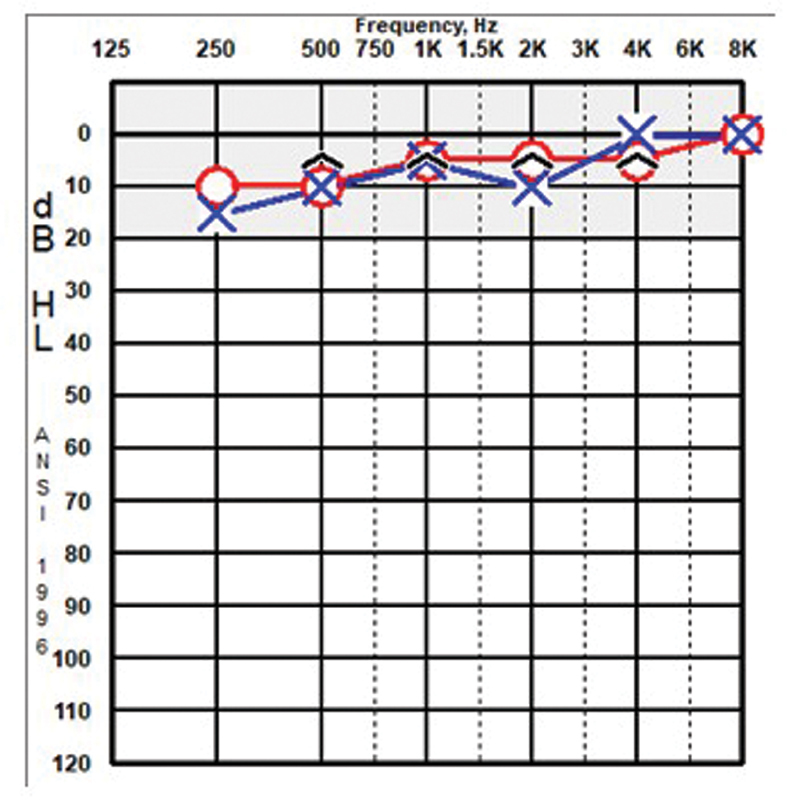

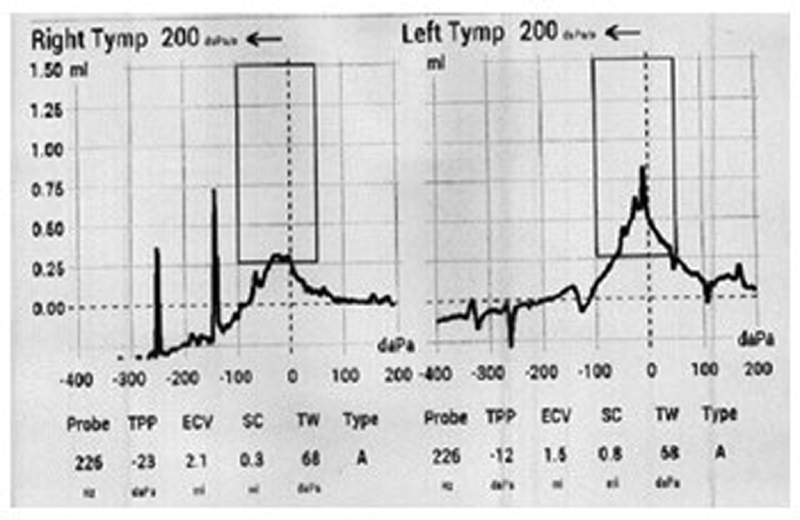

Otoscopy revealed a normal examination of the external auditory canals, tympanic membranes, and middle ears bilaterally. Comprehensive audiometric testing (see Fig. 1 ) was completed using foam insert earphones and revealed normal hearing sensitivity bilaterally. Voluntary responses were obtained and deemed to be of good reliability. Word recognition in quiet at conversational levels was 100% bilaterally (obtained using recorded NU-6 [Northwestern University Auditory Test Number Six] lists). Tympanometry (see Fig. 2 ) was consistent with normal middle ear pressure, compliance, and ear canal volumes bilaterally.

Figure 1.

Comprehensive audiometry.

Figure 2.

Tympanometry.

Allison received diagnoses of hyperacusis and subjective tinnitus. The ENT provider recommended that she follow up with her primary care physician to consider management of anxiety and referred to her to audiology for an evaluation of her DST and tinnitus.

Her first in-person appointment in the Audiology Clinic occurred approximately 1 month after her ENT evaluation. On this day, she reported that the tinnitus was not bothersome and that DST was her primary concern. Because clinical management of tinnitus and DST focuses on reducing the reactions to bothersome tinnitus and environmental sounds, validated questionnaires are a common method of evaluating the severity of these reactions. The HQ, 12 Inventory of Hyperacusis Symptoms (IHS), 14 and Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) 16 were administered to Allison. The HQ is a 14-item scale that was proposed in 2002 as a tool to quantify and evaluate symptoms of hyperacusis 12 and is used by many to aid in the diagnosis of hyperacusis. 11 The IHS was developed in 2018 after the authors noted the lack of a valid, standardized questionnaire for hyperacusis. 14 The A-MISO-S is a six-item scale that was developed in 2013 to measure the severity of symptoms of misophonia. 16 Please see Table 1 for a summary of Allison's baseline questionnaire results.

Table 1. Allison's Baseline Questionnaire Scores.

| Questionnaire | Allison's score | Interpretation of Allison's score |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ) | 15/42 | There is a suggested diagnostic criterion of 28 points, 12 although subsequent findings have suggested that this criterion should be reevaluated 43 |

| Inventory of Hyperacusis Symptoms (IHS) | 75/100 |

Scores ≥69 indicate the likelihood of hyperacusis

14

A subsequent evaluation of this tool suggested that a cutoff score of 56 most accurately identifies the presence of hyperacusis 44 |

| Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) | 18/24 | Scores between 15 and 19 suggest that the sufferer is experiencing severe symptoms 16 |

Allison's questionnaire results (suggesting that she experiences severe symptoms of misophonia and may experience hyperacusis) were consistent with her description of her reaction to bothersome environmental sounds. She reported that she had been living with ADD and self-diagnosed misophonia since she was in fourth grade, although she had never formally sought treatment for misophonia prior to this appointment. She reported that she was effectively managing ADD with a prescription medication. Her most bothersome triggers reportedly included chewing, typing, loud breathing, snoring, slurping, and hearing the television from another room through the walls. At the time of this evaluation, she lived at home with her parents and was consistently bothered by sounds made by both of them. She reported that she works as a software engineer and typically works in an office, although she was working from home at the time due to workplace restrictions put in place because of the COVID-19 pandemic. When in the office, she reported that she is bothered by sounds generated by a specific coworker and, unfortunately, is not able to escape the sounds because her team works in a large, open room together. She reported that she has tried noise-canceling headphones but did not like them and did not feel they were effective in reducing her awareness of bothersome environmental sounds. Environmental background sounds were reported to help her tolerate some bothersome triggers. She reported that the most notable impact of DST on her life was the decreased social time that she was willing to spend with her family. Although she described herself as a “big family person,” she felt that she could not tolerate time spent with her parents when they were the source of bothersome sounds. Additionally, Allison ranked the severity of her sound tolerance problem, her annoyance level due to this problem, and the overall impact of DST on her life as 8/10 problems on a visual analog scale (VAS) (with 0 being no problem and 10 being the worst problem).

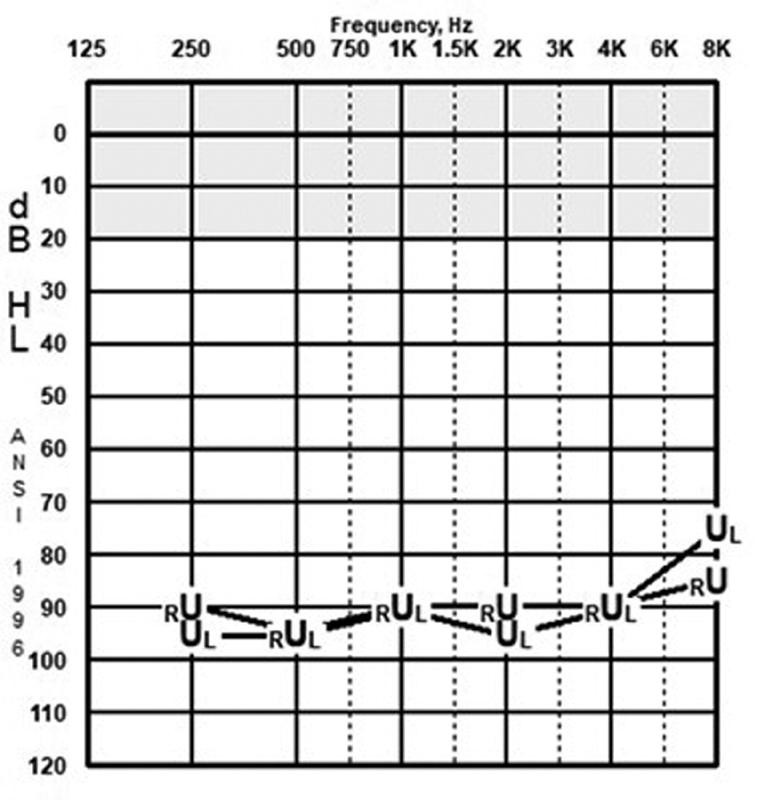

ULLs were obtained using the Contour Test of Loudness Perception. 36 During this procedure, patients will assign a number ranging from 1 (very soft) to 7 (uncomfortably loud) to each sound that is presented to them. In this case, the reason to obtain ULL responses was to inform the diagnosis of hyperacusis. For adults with normal hearing and no reports of DST, ULLs are typically recorded around 100 dB HL. 37 Allison's pure tone ULL results ( Fig. 3 ) were present between 75 and 95 dB HL across the pure tone frequency spectrum. Speech ULLs were 85 dB HL in the left ear and 90 dB HL in the right ear. With an ULL min of 90 dB HL for the left ear and a HQ score of 15, Allison did not meet either of the recommended hyperacusis criteria specified previously in this report. 11 Additionally, although she reported that she does not like loud sounds, misophonic triggers were her primary concern and had the most significant impact on her life.

Figure 3.

Uncomfortable loudness levels (ULLs).

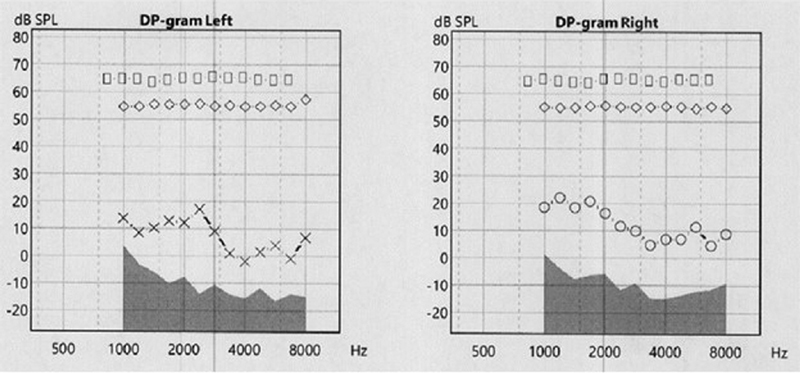

Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) are an objective measurement that are used to measure cochlear function (specifically, outer hair cell function). Allison's distortion product OAEs (DPOAEs) were robust, as evidenced in Fig. 4 , and consistent with normal outer hair cell function across the frequency spectrum. Input/output (I/O) functions and contralateral suppression measurements are not measurements with clinical applicability and were not recorded.

Figure 4.

Distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs).

The details of the TRT protocols used for misophonia 3 were discussed in addition to the out-of-pocket costs (i.e., TRT enrollment fee and on-ear devices). Allison was eager to begin, but first wanted to check her insurance coverage for on-ear devices. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is known to alleviate tinnitus-related distress, 38 and although there is evidence to support the use of CBT to reduce distress related to hyperacusis and misophonia (case studies and some limited randomized-controlled studies identified by Aazh et al 39 ), the evidence base lacks randomized-controlled trials. 39 This option was discussed with Allison and she reported that she was open to exploring this treatment route in addition to TRT. She wanted to think about her options but indicated she would contact the audiology clinic if she wanted to formally enroll in TRT.

Method

In the evening after her TRT evaluation appointment, Allison made contact via a secure electronic messaging system indicating that she was ready to enroll. The initial TRT visit is referred to as the “counseling” or “teaching” session because the goal is to provide informational counseling that begins the process of decreasing the strength of negative sound-related reactions and recategorizing the tinnitus or environmental sounds as neutral stimuli. 40 This appointment had traditionally been completed in-person in the clinic; however, as this counseling session is meant to facilitate a dialogue between the patient and the clinician, this appointment is well-suited for a video visit. Additionally, using a video format allows for sharing images and slides that aid in teaching the concepts that empower the patient to understand their own hearing anatomy and test results, suppression and enhancement of auditory signals, the process of habituation, the role of conditioned reflexes in bothersome tinnitus or DST, and the role of sound therapy. 41 See Fig. 5 for an example of one of the slides that was used during this teaching session. During the specific portion of the counseling appointment when this slide is being used, the discussion is focused on the neural systems involved when hyperacusis and misophonia are present. 1 Additionally, the picture on the bottom of the slide illustrates the ultimate goal of habituation of both the tinnitus perception and the resulting emotional and physical reactions. 40

Figure 5.

The on-ear devices can be discussed in detail during this video session. For a person suffering from DST, the goal of wearing on-ear devices is desensitization to bothersome sounds (for hyperacusis) or systematic exposure to sounds that have a pleasant association (for misophonia). 1 There are many ways to accomplish this end; on-ear devices are one option. Several protocols (detailed later in this report) are used for patients with misophonia to gradually increase their tolerance of bothersome sounds and strengthen their positive associations with other sounds. 3 During the discussion about the devices, slides that detail the available style, technology level, and accessory options were presented. Together, Allison and her audiologist determined what would best meet her needs. When the patient can wear open-fit devices that do not require a custom coupling, the devices can be ordered that same day. If an ear impression is required, the patient will need to schedule an appointment to come to the clinic for the ear impression(s). Allison decided to pursue receiver-in-canal (RIC) style devices with entry-level technology. Given her normal hearing status, these devices were planned to be fit with small, open, non-custom domes. Because this was a telemedicine visit, she paid the TRT enrollment fee over the phone using a credit card and was scheduled for her device delivery appointment. The devices were ordered.

On the day of her device delivery, programming was completed to provide Allison with some options for consistent exposure to sounds that she finds pleasing. The default setting produces a low level of pink noise, which she felt was soothing. Additionally, because the devices she chose could connect directly with her phone via Bluetooth she also had the option of streaming sounds from her phone. This capability vastly increased her options related to what kinds of sounds she will use to facilitate her development of positive sound associations because any sounds that she can access through her phone can be streamed through her devices into her ears. Allison signed the remote programming consent form, giving herself the option to access cloud-based remote programming in the future. Allison was taught how to operate and care for her devices.

Jastreboff and Jastreboff 3 described four misophonia-specific TRT protocols that are recommended for patients suffering from misophonia. These protocols are designed to facilitate positive associations with environmental sounds and gradually reduce the patient's control over sounds that they are hearing. Protocol 1 provides the patient with full control over the sound (including the type of sound, the presentation level, and the duration of listening). As Jastreboff and Jastreboff 3 described, the goals of this protocol are twofold: “to increase a positive association with a favorite type of sound and to gradually increase the level of sound considered to be optimal.” This protocol involves a 3-week cycle. During the first week, the patient is instructed to listen with intention to a sound they like once or twice a day for 15 to 30 minutes at an intensity level that they find to be pleasant. The next week, they will increase the volume slightly. During the third week, they will increase the volume by two noticeable steps. Over time, the aim is to develop strongly positive associations with sound that will spread to other sounds. In contrast, Protocol 4 combines bothersome sounds with sounds that have strong positive associations. Please see the article by Jastreboff and Jastreboff 3 for a full description of the four protocols. Allison was introduced to Protocol 1 on the day of her device fitting. She indicated that she would be likely to use music as her sound of choice for the first iteration of this protocol. It was discussed that many patients choose to repeat this 3-week cycle more than once until they feel that a strong positive association has been formed with their favorite sounds.

Relevant warranty information was reviewed. Allison reported that, though she currently lived alone and worked from home, she was likely to be going back to work in her office soon and would be in touch with questions about adapting her treatment to a new setting. She paid for her devices and associated services and scheduled a 3-week video follow-up appointment.

Results

In the evening of the day of her device fitting, Allison sent an electronic message to her audiologist requesting a remote programming adjustment to increase the default intensity level of the pink noise in her devices. An appointment time was scheduled and a remote programming session (i.e., with Allison physically located in her home and her audiologist located in the office) was completed to increase the default volume to her satisfaction. They agreed to follow up as already scheduled in approximately 3 weeks.

Three weeks later, during another video follow-up appointment, Allison described that she felt things were going well with the protocol. She reported that she was listening to sounds that she enjoys very much (typically her favorite television shows) and that she had no questions about further implementation of this protocol. She did indicate that she was having trouble keeping her devices on her ears when putting her mask on and taking it off. These interactions occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, when universal masking was recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to reduce the transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus. 42 Some strategies for keeping her mask strap off of her ears (e.g., using a mask with ties that go behind the head instead of ear loops, using a plastic mask strap that stretches the ear loops off of the ears) were shared. Allison was encouraged to complete another cycle of Protocol 1 to further strengthen the positive associations that were forming. Another video follow-up was scheduled in 3 weeks.

Discussion

Allison is a 23-year-old woman who had been living with severe misophonia since childhood. Before enrolling in TRT, she was not aware of any formal treatment options for misophonia. This case report details her evaluation of DST and the beginning stages of her treatment.

As previously discussed, the process for diagnosing hyperacusis is a topic that has been debated. In 2017, Aazh and Moore recommended the following criteria: ULL min (average ULL at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 kHz for the ear with the lower average ULL) ≤77 dB HL and a score of ≥22 on the HQ. 11 With an ULL min of 90 dB HL and a HQ score of 15, Allison did not meet either criteria, although her score on the IHS (75/100) indicated that she was likely to suffer from hyperacusis. The questionnaire recommended by Aazh and Moore, 11 the HQ, was developed in 2002 and has been widely used, although a subsequent study has identified concerns about its validity. 43 The IHS has since been proposed. 14 Individuals scoring 69/100 on the IHS are likely to experience hyperacusis as somewhat of a problem (with 80 and 89 being the cutoff thresholds for “quite a bit of a problem” and “extreme problem” categories, respectively). 14 Aazh et al proposed a 56-point cutoff criterion 44 ; this would not have changed the interpretation of Allison's score (75/100). Upon initial evaluation, the IHS demonstrated excellent reliability and good validity in evaluating the severity of the impact of hyperacusis on an individual, 14 with subsequent data reporting good internal consistency and reasonably high convergent validity. 44 A subsequent evaluation of the IHS revealed that the score on this instrument is moderately correlated with scores for the HQ, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); these correlations suggested that IHS scores also reflected the co-occurrence of tinnitus, anxiety, and depression. 44 The discrepancy in determining the likelihood of the presence of hyperacusis (i.e., Allison not meeting Aazh and Moore's criteria but scoring >69 on the IHS) suggests that these scales and criteria (and the process of diagnosing hyperacusis as a whole) may benefit from further evaluation.

A recent study evaluated the readability of several hyperacusis scales (including both the HQ and the IHS), finding that all questionnaires studied were close to or exceeded the recommended grade levels recommended by the American Medical Association and National Institutes of Health. 45 A recent study 46 proposed a list of sounds (referred to as the core discriminant sounds) that were rated by individuals on a visual analog scale (pleasant to unpleasant); mean scores between control subjects and subjects identified as having hyperacusis were significantly different. This method has been proposed as a clinical alternative to ULL measurements and may be of interest in future evaluations.

The A-MISO-S was developed in 2013. 16 Some clinicians may have been hesitant to use it initially due to a lack of published psychometric data, but a recent publication found that the A-MISO-S is a robust measure of misophonia with good internal consistency. 47 Although there are currently no data to suggest how much of a change in A-MISO-S score would be considered clinically significant (David Baguley, Ph.D. Date of communication: 2/15/21 Communication occurred via e-mail), researchers have considered a 30% reduction 48 or a four-point mean difference 49 in score to be a positive treatment outcome. A recent publication proposed an updated version of this questionnaire called the Amsterdam Misophonia Scale-R (A-MISO-R), which is undergoing the validation process. 5 Early results appear to show good reliability and validity of this revised scale. 49 Allison's initial score (18/24) suggests that she experiences severe symptoms of misophonia. 16 This scale will be repeated throughout the TRT process, as will her rankings of her perception of the severity of DST, her annoyance level, and the overall impact on her life. These outcomes will provide several data points to track progress throughout the program.

Allison reported a history of ADD which she reported was being managed successfully with the amphetamine prodrug Vyvanse. There is a body of literature to support the idea that deficits in attention may play a role in the misophonic response. 5 50 51 52 53 54 Individuals with misophonia may report that they have difficulty tuning out sounds that typically would be considered “background noise” or specific trigger sounds. 52 These deficits may be electrophysiologically measurable, as Schröder et al reported reduced N1 amplitude; the N1 response is thought to play a role in auditory attention. 53

The role of OAEs in the evaluation and management of patients with DST is not entirely clear. It can be a useful counseling tool that empowers patients by helping them to understand the physiology and function of their individual auditory system (serving as a visual representation of an intangible concept). Beyond that, there is some evidence that DPOAE amplitudes or input/output (I/O) functions measured in individuals with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis may differ from control groups, although a causal relationship cannot currently be determined. 55 Additionally, the medial olivocochlear (MOC) system is postulated to play a role in tinnitus and/or hyperacusis and differences have been noted in MOC function as measured by contralateral suppression of OAEs in these individuals. 56

Multiple reports suggest that TRT has been used to successfully treat DST. Implementation of a TRT protocol for hyperacusis resulted in increases in sound tolerance in 81% of patients with DST. 57 Following that study, outcomes from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial suggested that 80% of participants who received treatment improved significantly (measured by audiometric testing including ULLs). 23 Jastreboff and Jastreboff have reported an 83% success rate in treating misophonia (measured by an improvement in their judgment of the severity of their DST, annoyance response to it, effect on their lives, and their ranking of how much of a problem they consider DST to be on a scale from 0 [no problem] to 10 [the biggest problem they could imagine]). 3 26 In these reports, some patients noticed an improvement in the first 3 months and the majority improved significantly between 9 and 18 months after the treatment onset. 3 26 As Allison progresses through the TRT protocols, she is hopeful that she will maintain a similar trajectory.

The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in a new world of virtual care. 58 Audiologists were not immune to this shift and have adapted to this new reality. By doing so, we acknowledge that although certain procedures will always require in-person visits, the availability of hybrid-care pathways will serve our patients by increasing access to the necessary services that we provide. 59 The impact of remote device programming (i.e., the ability to program on-ear devices while the patient and provider are in separate, remote locations) and telecare on the treatment of DST are not well documented. Allison's on-ear devices were manufactured by GN Resound. This specific manufacturer affords users the capability to utilize cloud-based connections to complete fine-tuning adjustments via a smartphone application. 60 Use of this specific application was evaluated in hearing aid wearers. The remote programming capability was rated as highly usable and addressed several issues that required fine-tuning adjustments. 61 Recent research has indicated that teleaudiology hearing device follow-up care (and blended care that combines face-to-face and remote care) is not considered to be different from standard (i.e., in-person) care. 62 Allison has completed two in-person visits (TRT evaluation, device delivery) and three teleaudiology visits (TRT teaching session, remote programming adjustment, 3-week follow-up). While her satisfaction was not measured formally, she expressed that she appreciated the opportunity to address programming issues, ask questions, and receive advice from her own home. This blended model of telecare is expected to continue throughout the remainder of her treatment. Although experts suggest that telehealth options may benefit patients with uncommon conditions such as DST, 63 64 65 the application of teleaudiology (and specifically, blended or hybrid teleaudiology) in treating DST is a research area requiring more attention.

Conclusion

Allison, a 23-year-old woman suffering from longstanding DST, began the process of treating severe misophonia by enrolling in TRT. Her evaluation and treatment took place via a hybrid teleaudiology model that improved access to audiologic care. She is still in the early stages of the expected TRT timeline but has embraced the telemedicine option by completing three of her five visits remotely. Although this option was attractive to her, the use of telemedicine in the evaluation and treatment of DST is an area where research is lacking. Given the rise in telemedicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is reasonable to expect that patients who have been evaluated or treated via telemedicine may wish to continue their expanded access to audiologic care.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Jastreboff M, Jastreboff P. Decreased sound tolerance and tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) Aust N Z J Audiol. 2002;24(02):74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jastreboff P, Jastreboff M.Decreased sound tolerance: hyperacusis, misophonia, diplacousis, and polyacousis Handb Clin Neurol 2015129375–387..https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00021-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jastreboff P, Jastreboff M.Treatments for decreased sound tolerance (hyperacusis and misophonia) Semin Hear 20143502105–120..https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1372527 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baguley D M, Hoare D J.Hyperacusis: major research questions HNO 20186605358–363..https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-017-0464-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jager I, de Koning P, Bost T, Denys D, Vulink N. Misophonia: phenomenology, comorbidity and demographics in a large sample. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231390. PLoS One. 2020;15(04):e0231390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alekri J, Al Saif F.Suicidal misophonia: a case report Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol 20192902232–237..https://doi.org/10.1080/24750573.2019.1597585 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aazh H, Knipper M, Danesh A. Insights from the third international conference on hyperacusis: causes, evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Noise Health. 2018;20(95):162–170. doi: 10.4103/nah.NAH_2_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaesing L, Kroener-Herwig B.Self-reported and behavioral sound avoidance in tinnitus and hyperacusis subjects, and association with anxiety ratings Int J Audiol 20125108611–617..https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2012.664290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anari M, Axelsson A, Eliasson A, Magnusson L.Hypersensitivity to sound--questionnaire data, audiometry and classification Scand Audiol 19992804219–230..https://doi.org/10.1080/010503999424653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheldrake J, Diehl P U, Schaette R.Audiometric characteristics of hyperacusis patients Front Neurol 20156(MAY):105.https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2015.00105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aazh H, Moore B CJ.Factors related to uncomfortable loudness levels for patients seen in a tinnitus and hyperacusis clinic Int J Audiol 20175610793–800..https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1335888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalfa S, Dubal S, Veuillet E, Perez-Diaz F, Jouvent R, Collet L.Psychometric normalization of a hyperacusis questionnaire ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 20026406436–442..https://doi.org/10.1159/000067570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dauman R, Bouscau-Faure F.Assessment and amelioration of hyperacusis in tinnitus patients Acta Otolaryngol 2005125503–509..https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480510027565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg B, Carlos M.Psychometric properties and factor structure of a new scale to measure hyperacusis: introducing the Inventory of Hyperacusis Symptoms Ear Hear 201839051025–1034..https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabhu P, Nagaraj M K.Development and validation of Hyperacusis Handicap Questionnaire in individuals with tinnitus associated with hyperacusis J Otol 20201504124–128..https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joto.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schröder A, Vulink N, Denys D. Misophonia: diagnostic criteria for a new psychiatric disorder. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054706. PLoS One. 2013;8(01):e54706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dozier T H, Lopez M, Pearson C.Proposed diagnostic criteria for misophonia: a multisensory conditioned aversive reflex disorder Front Psychol 20178(Nov):1975.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu M S, Lewin A B, Murphy T K, Storch E A.Misophonia: incidence, phenomenology, and clinical correlates in an undergraduate student sample J Clin Psychol 20147010994–1007..https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitoratou S, Hayes C, Uglik-Marucha E, Gregory J. Selective Sound Sensitivity Syndrome Scale (S-Five): a psychometric tool for assessing misophonia. Summary on three waves of sampling and analysis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4dzqn https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4dzqn

- 20.Siepsiak M, Śliwerski A, Łukasz Dragan W. Development and psychometric properties of MisoQuest - a new self-report questionnaire for misophonia. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051797. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(05):1797. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pienkowski M, Tyler R S, Rojas Roncancio E.A review of hyperacusis and future directions: Part II. Measurement, mechanisms, and treatment Am J Audiol 20142304420–436..https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJA-13-0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold S, Frederick E, Formby C.Shifts in dynamic range for hyperacusis patients receiving tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT)In: Proceedings of the Sixth International Tinnitus SeminarLondon: 1999297–301.

- 23.Formby C, Hawley M, Sherlock L.Intervention for restricted dynamic range and reduced sound tolerance: clinical trial using a tinnitus retraining therapy protocol for hyperacusisIn: Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. Vol 19. Acoustical Society of America (ASA)Montreal: 201350083–50083.https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4799870

- 24.Jastreboff P J.Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception Neurosci Res 1990804221–254..https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-0102(90)90031-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jastreboff P J, Jastreboff M M. Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) as a method for treatment of tinnitus and hyperacusis patients. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11(03):162–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jastreboff M, Jastreboff P. Misophonia and its treatment. J Hear Sci. 2017;7(02):83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Ffmch-2020-000530. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(03):530. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2020-000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagge D, Knopf A, Hofauer B.[Telemedicine in the fight against SARS-COV-2-opportunities and possible applications in otorhinolaryngology: narrative review] HNO 20206806433–439..https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-020-00864-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guitton M J. Telemedicine in tinnitus: feasibility, advantages, limitations, and perspectives. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/218265. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:218265. doi: 10.1155/2013/218265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Matos I L, Ferreira M C, Mondelli M FCG.Development and evaluation of portal do zumbido: a novel telehealth approach to tinnitus Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 20212502e258–e266..https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1709113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry J A, Zaugg T L, Myers P.Pilot study to develop telehealth tinnitus management for persons with and without traumatic brain injury J Rehabil Res Dev 201249071025–1042..http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2010.07.0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aazh H, Swanepoel D W, Moore B CJ.Telehealth tinnitus therapy during the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK: uptake and related factors Int J Audiol 20216005322–327..https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1822553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.List R, Compton M, Soper M.Preserving multidisciplinary care model and patient safety during reopening of ambulatory cystic fibrosis clinic for nonurgent care: a hybrid telehealth model Telemed J E Health 20212702193–199..https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makkar A, McCoy M, Hallford G. Evaluation of neonatal services provided in a level II NICU utilizing hybrid telemedicine: a prospective study. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0262. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(02):176–183. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makkar A, Milsten J, McCoy M.Tele-echocardiography for congenital heart disease screening in a level II neonatal intensive care unit with hybrid telemedicine systemTelemed J E Health2021https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0440 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Cox R M, Alexander G C, Taylor I M, Gray G A. The contour test of loudness perception. Ear Hear. 1997;18(05):388–400. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherlock L P, Formby C.Estimates of loudness, loudness discomfort, and the auditory dynamic range: normative estimates, comparison of procedures, and test-retest reliability J Am Acad Audiol 2005160285–100..https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.16.2.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hesser H, Weise C, Westin V Z, Andersson G.A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy for tinnitus distress Clin Psychol Rev 20113104545–553..https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aazh H, Landgrebe M, Danesh A A, Moore B C.Cognitive behavioral therapy for alleviating the distress caused by tinnitus, hyperacusis and misophonia: current perspectives Psychol Res Behav Manag 201912991–1002..https://dx.doi.org/10.2147%2FPRBM.S179138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jastreboff P J. New York: Springer; 2011. Tinnitus retraining therapy; pp. 575–596. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jastreboff P, Jastreboff M. Columbia, MD: 2013. Tinnitus Retraining Therapy for Management of Tinnitus and Hyperacusis. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Use Masks to Help Slow Spread | CDCAccessed February 13, 2021 at:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/diy-cloth-face-coverings.html

- 43.Fackrell K, Fearnley C, Hoare D J, Sereda M. Hyperacusis Questionnaire as a tool for measuring hypersensitivity to sound in a tinnitus research population. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/290425. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:290425. doi: 10.1155/2015/290425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aazh H, Danesh A A, Moore B CJ.Internal consistency and convergent validity of the Inventory of Hyperacusis SymptomsEar Hear 2020 (epub ahead of print).https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000000982 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Margol-Gromada M, Sereda M, Baguley D M.Readability assessment of self-report hyperacusis questionnaires Int J Audiol 20205907506–512..https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1723033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Enzler F, Fournier P, Noreña A J. A psychoacoustic test for diagnosing hyperacusis based on ratings of natural sounds. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2020.108124. Hear Res. 2021;400:108124. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2020.108124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naylor J, Caimino C, Scutt P, Hoare D J, Baguley D M.The prevalence and severity of misophonia in a UK undergraduate medical student population and validation of the Amsterdam Misophonia Scale Psychiatr Q 2020(August):1–11.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-020-09825-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schröder A E, Vulink N C, van Loon A J, Denys D A. Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in misophonia: an open trial. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.017. J Affect Disord. 2017;217:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jager I J, Vulink N CC, Bergfeld I O, van Loon A JJM, Denys D AJP.Cognitive behavioral therapy for misophonia: a randomized clinical trialDepress Anxiety 2020; (epub ahead of print)https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Ralli M, Romani M, Zodda A. Hyperacusis in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a preliminary study. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093045. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(09):3045. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amir I, Lamerton D, Montague M L.Hyperacusis in children: the Edinburgh experience Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 201811239–44..https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edelstein M, Brang D, Rouw R, Ramachandran V S.Misophonia: physiological investigations and case descriptions Front Hum Neurosci 20137(Jun):296.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schröder A, van Diepen R, Mazaheri A.Diminished n1 auditory evoked potentials to oddball stimuli in misophonia patients Front Behav Neurosci 20148(Oct):123.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva F ED, Sanchez T G.Evaluation of selective attention in patients with misophonia Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed) 20198503303–309..https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartnik G, Hawley M, Rogowski M, Raj-Koziak D, Fabijanska A, Formby C.[Distortion product otoacoustic emission levels and input/output-growth functions in normal-hearing individuals with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis] Otolaryngol Pol 20096302171–181..https://doi.org/10.1016/s0030-6657(09)70102-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knudson I M, Shera C A, Melcher J R.Increased contralateral suppression of otoacoustic emissions indicates a hyperresponsive medial olivocochlear system in humans with tinnitus and hyperacusis J Neurophysiol 2014112123197–3208..https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00576.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Formby C, Gold S L, Keaser M L, Block K L, Hawley M L.Secondary benefits from tinnitus retraining therapy: clinically significant increases in loudness discomfort level and expansion of the auditory dynamic range Semin Hear 20072804227–260..https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-990713 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B.Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care J Am Med Inform Assoc 20202706957–962..https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saunders G H, Roughley A.Audiology in the time of COVID-19: practices and opinions of audiologists in the UK Int J Audiol 2020(September):1–8.https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1814432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.ReSound Smart 3D Hearing Aid App | ReSoundAccessed February 15, 2021 at:https://www.resound.com/en-us/hearing-aids/apps/smart-3d

- 61.Convery E, Keidser G, McLelland M, Groth J.A smartphone App to facilitate remote patient-provider communication in hearing health care: usability and effect on hearing aid outcomes Telemed J E Health 20202606798–804..https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2019.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tao K FM, Moreira T C, Jayakody D.Teleaudiology hearing aid fitting follow-up consultations for adults: single blinded crossover randomised control trial and cohort studies Int J Audiol 2020(September):1–12.https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1805804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sammons M T.How will the crises of 2020 shape the clinical practice of psychology in 2021? J Health Serv Psychol 202147011–3..https://doi.org/10.1007/s42843-021-00031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vivas E X.Coronavirus disease-19 and otology/neurotology Otolaryngol Clin North Am 202053061153–1157..https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.otc.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abdala C, Visser-Dumont L. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions: a tool for hearing assessment and scientific study. Volta Review. 2001;103(04):281–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]