Abstract

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is classically described as a locally aggressive, epiphyseo-metaphyseal osteolytic tumor occurring in young adults. They are mostly seen in long bones while some are also found in the iliac bone and spine and a very small proportion occurs in hand bones. Due to the rarity of GCT in metacarpal, there is a paucity of treatment options available. In an extensive literature search on PubMed, Embase, Medline, and Ovid from 2004 till date, very few cases were reported.

The various treatment options available are intralesional curettage with or without adjuvant therapy, wide resection, free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer, and, occasionally, ray amputation may also be done. After simple curettage, a reasonably high recurrence rate also imposes comprehensive en-bloc excision, but still, there are many case reports of recurrence.

Experience with a case of GCT of the whole first metacarpal extending from the carpometacarpal to the metacarpophalangeal joint is not thoroughly described in the literature. We hereby report a mammoth GCT of the first metacarpal treated by excision and reconstruction by free fibular graft and adjacent joint fusion with an excellent functional outcome at one-year follow-up.

Keywords: giant cell tumor, dual joint fusion, fibula graft, first metacarpal, complete excision and reconstruction

Introduction

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is described as a locally aggressive, osteolytic tumor occurring in young adults at the epiphyseal region. Around 80%-90% of giant cell tumors are seen in long bones, 4% in the iliac spine and iliac bone, and only 2% of giant cell tumors are described in hand. (the phalanges, rarely, are located within the thumb and metacarpals). Unni reports an incidence of 1.7% for giant cell tumors of metacarpals [1]. According to Averill et al., less than 1.5% of giant cell tumors are reported in metacarpal [2]. Due to the rarity of GCT in metacarpal, there is a paucity of treatment options available. In an extensive literature search from 2004 till date, only 22 cases were reported.

The various treatment options available are intralesional curettage with or without adjuvant therapy, wide resection of the tumor, followed by joint reconstruction by allograft or arthroplasty, joint arthrodesis augmented with bone graft, free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer, and, occasionally, ray amputation. Initially, after curettage followed by autologous bone graft, around 90% of recurrence was reported [3], leading to extensive en block excision of the tumor as the only option [4]. We hereby report our experience with a case of GCT of the whole first metacarpal extending from carpometacarpal to metacarpophalangeal joint and discussing all possible treatment options available for metacarpal GCT.

Most of the GCT of the first metacarpal is small and retractable. We are reporting a case of mammoth GCT of the first metacarpal, which was treated by excision and reconstruction by free fibular graft and adjacent joint fusion.

Case presentation

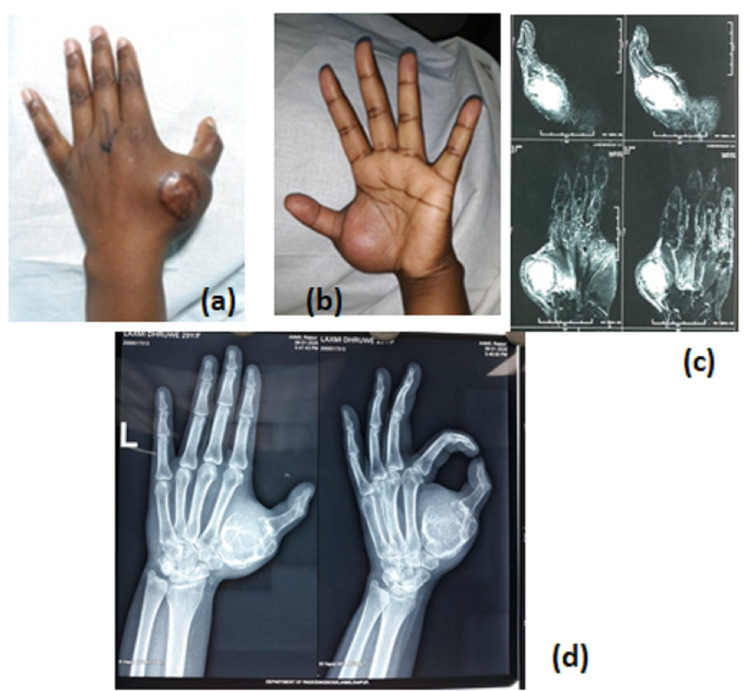

A 29-year-old female came to the orthopedic outpatients' department (OPD) with a complaint of swelling of her left thumb with global restriction of thumb movement. The swelling was gradually progressive and associated with pain. There was no history of any constitutional symptoms or any injury. Initially, the patient had taken an indigenous system of treatment in the form of local ointment and heat application and developed a skin reaction; thereafter, the patient came to the orthopedics department. The patient had undergone a core needle biopsy with the diagnosis of GCT on histopathology. On physical examination, there was localized swelling over the right first metacarpal, of size around 10 x 7 x 4.5 cm, with variable consistency. The overlying skin was scarred with adhesion on the needle biopsy site, and the movements of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and trapeziometacarpal joints were painful and restricted.

Roentgenogram revealed an expansile osteolytic lesion of the first metacarpal in totality with a pathological fracture (Figure 1, panel d). A magnetic resonance scan (Figure 1, panel c) showed a 7.6 x 6.6 x 4.2 cm mass, which involved the whole first metacarpal in totality. The swelling was adherent to the skin and lesion on the biopsy site near the MCP joint. It was decided to excise the involved metacarpal in totality and reconstruct the thumb by a free fibula graft and adjacent joint fusion.

Figure 1. (a, b) Clinical picture of the left thumb, (c) MRI, and (d) radiograph showing expansile osteolytic lesion of the first metacarpal.

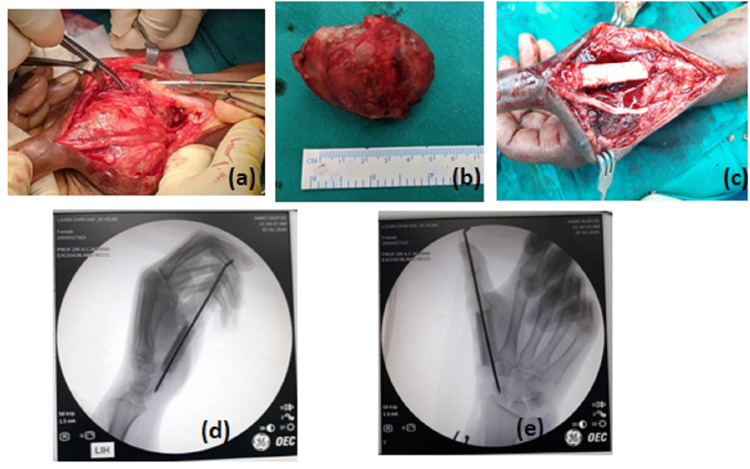

A dorsal longitudinal incision was given, extending from the first carpal metacarpal joint to the first proximal phalanx, crossing over the center of swelling. The skin and tendons over the swelling were retracted and extension tendons were cleared by a sharp knife and thermocautery. En-block resection of the tumor was done. The same length of the diaphyseal fibula was excised from the middle one-third of the left leg. To promote the union process, the articular surface of the trapezium was shoveled to expose good cancellous bone for fusion. A free fibular graft of size of the first metacarpal was fixed between proximal phalanx and trapezium in 40-degree abduction and flexion with the help of 2.6 mm transarticular Kirschner wire to achieve arthrodesis of the trapezium and proximal phalanx with fibula graft (Figure 2) in the functional position. The fibula graft was covered by the surrounding interosseous muscles and the incision site was closed in layers. A unilateral thumb spica slab was given postoperatively and was replaced by a spica cast after suture removal on the 14th day after surgery.

Figure 2. (a) Intraoperative tumor with extensive soft tissue involvement. (b) En-block resection of the GCT. (c-e) Clinical and IITV image with transfixed free fibula bone graft.

IITV: image intensifying television

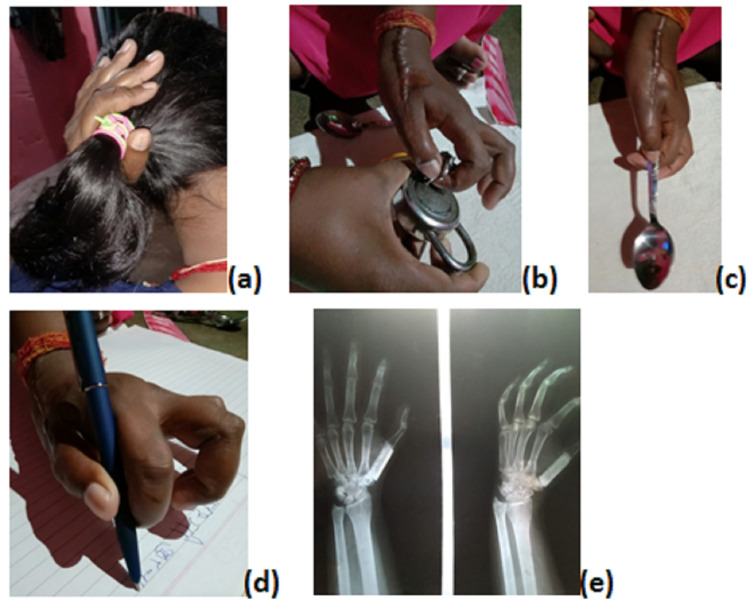

Postoperatively, the excised specimen was confirmed as GCT on histopathological examination. The Kirschner wire, along with a thumb spica cast, was removed three months after the surgery. Thumb and wrist range of motion exercises were then started. Postoperative radiograph at 12 months showed a well-accepted fibula graft fused distally with first proximal phalanx and proximally with trapezium, with not a radiological sign of tumor recurrence and the patient has an optimum functional thumb (Figure 3).

Figure 3. (a) One-year follow-up radiograph showing well-accepted fibula and adjacent joint fusion. (b) Functional thumb with span grip. (c,d) functional pinch grip, (e) functional ventral clenched grip.

Discussion

Giant cell tumor accounts for about 4%-5% of all bone tumors and around 20% of benign bone malignancies. Most GCT are locally aggressive, but their course of progression is unpredictable, as many cases of distal metastasis are also reported in the literature [5]. GCT is mainly seen in long bone (around 75%-90% in the distal femur followed by 25% in the upper end of tibia, distal radius, and humerus [1] and only 1.7% to 4% in hand bones [1-3].

GCT of the hand are more locally aggressive, so in comparison to other long bone giant cell tumors, the signs and symptoms appear rapidly and expound even in the younger patients.

GCT usually present with clinical features of swelling and pain. It affects typically the epiphysis and epiphysis metaphysis region of the metacarpal. The differentials include aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), non-ossifying fibroma, and osteosarcoma [6-7]. A management protocol of the giant cell tumor in metacarpal has not progressed very much in the past few decades, due to the less availability of cases in the literature. Versatile modalities available with us are intralesional curettage with or without adjuvant therapy, wide resection, joint reconstruction techniques, including total joint replacement, allograft reconstruction, joint arthrodesis augmented with bone graft, free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer, and, occasionally, ray amputation.

We reviewed 23 (27 patients) case reports of metacarpal GCT (including ours) that have been published in the English literature from 2004 till now. Eleven patients were male, and 16 were female, with 19 on the right hand and eight on the left. GCT in the first metacarpal was in eight patients, second metacarpal in five patients, third metacarpal in one patient, fourth metacarpal in eight patients, and five patients with fifth metacarpal involvement. Metacarpal GCT is most commonly noted in the second and third decades of life (Table 1).

Table 1. Reported cases of metacarpal GCT.

GCT: giant cell tumor

| Series | Number of case | Age | Sex | Side | Site | Treatment of the reported case | |

| 01 | A Chatterjee, D. B. Dholakia, and S. V. Vaidya, 2004 [8] | 01 | 18 year | Male | Right | 1st metacarpal | Excised en masse and replaced with a silastic spacer |

| 02 | Marco Manfrini, et al. 2004 [9] | 01 | 32 year | Male | Right | 4th metacarpal | En mass resection with fibular autograft and silicone implant arthroplasty |

| 03 | Tatsuya Yoshida, et al. 2007 [10] | 02 | 7 year | Female | Right | 2nd metacarpal | Curettage, followed by phenol and ethanol application and then bone grafting |

| 23 year | Male | Right | 4th metacarpal | ||||

| 04 | P. P. Kotwal, C. Nagaraj, and V. Gupta, 2008 [11] | 02 | 30 year | Female | Right | 2nd metacarpal | Marginal excision of the tumor followed by reconstruction with a reversed vascularised toe joint transfer |

| 32 year | Female | Right | 2nd metacarpal | ||||

| 05 | Mounir Arroud, et al. 2010 [12] | 01 | 8 year | Male | Right | 4th metacarpal | Complete resection of the fourth metacarpal bone and reconstructed with a free fibular graft |

| 06 | Mohammad Shahid, et al. 2011 [13] | 01 | 30 year | Male | Right | 1st metacarpal | En bloc resection with morselised iliac corticocancellous bone grafts |

| 07 | Patrick Jaminet, et al. 2010 [14] | 01 | 28 year | Male | Right | 2nd metacarpal | Reconstruction with free vascularized scapular bone flap combined with nonvascularized free osteocartilaginous grafts from the second toe |

| 08 | Hunaina Al-Kindi, et al. 2011 [15] | 01 | 34 year | Female | Right | 1st metacarpal | Curettage followed by local resection and bone grafting |

| 09 | Neil F. Jones, et al. 2012 [16] | 01 | 66 year | Female | Right | 4th metacarpal | Metacarpal and MCP Joint reconstruction using a fibular osteocutaneous free flap and silicone arthroplasty |

| 10 | Jin Chang Moon, et al. 2012 [17] | 01 With pulmonary metastasis | 54 year | Male | Left | 2nd metacarpal | Curettage followed with chemotherapy (adriamycin and cisplatin) |

| 11 | Keith Jackson, et al. 2012 [18] | 01 Recurrent after 43 years | 69 year | Male | Right | 4th metacarpal | Intralesional excision and autogenous bone grafting |

| 12 | Lalit Maini, et al. 2011 [19] | 01 | 25 year | Female | Right | 5th metacarpal | Enbloc resection of the tumor with free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer |

| 13 | Salim Al Lahham, et al. 2013 [20] | 01 | 06 year | Female | Left | 5th metacarpal | Complete excision with the reconstruction of the defect with 2nd phalanx of the third toe |

| 14 | Nash H. Naam, et al. 2013 [21] | 01 | 25 year | Female | Left | 4th and 5th metacarpal | Wide local excision and ray amputation |

| 15 | Soobin Lim et al. 2016 [22] | 01 | 63 year | Female | Right | 1st metacarpal | Stage I – excision-bone cement spacer with external fixator application; Stage II – Tricortical iliac crest graft with adjacent joint fusion |

| 16 | Athanasian EA, 2004 [23] | 01 | 51 year | Male | Right | 5th metacarpal | Reconstruction of the entire fifth metacarpal bone after en-bloc resection with a Y-shaped bone fusion to the fourth metacarpal |

| 17 | Paweł Reichert, et al. 2017 [24] | 01 | 25 year | Female | Left | 1st metacarpal | Stage I – excision of the tumor with external fixator application; Stage II – the corticocancellous bone graft from the iliac crest with k wire fixation |

| 18 | Thipachart Punyaratabandhu, et al. 2017 [25] | 01 | 37 year | Female | Left | 1st metacarpal | Stage I – excision of the first metacarpal with cement spacer application; Stage II – titanium prosthesis application with ligament reconstruction |

| 19 | Laura W, et al. 2017 [26] | 01 | 57 year | Female | Right | 4th metacarpal | Excision of the tumor with 1 cm safe margin and fresh-frozen allograft metacarpal |

| 20 | Pankaj Kumar Mishra, et al. 2017 [27] | 01 | 13 year | Female | Right | 5th metacarpal | Free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer |

| 21 | Bokemper MK, et al. 2016 [28] | 01 | 23 year | Male | Right | 3rd metacarpal | Third-ray resection and limited midcarpal fusion |

| 22 | Kabul C Saikia, et al. 2011 [29] | 02 | 24 year | Female | Left | 4th metacarpal | Ray resection of the ring finger |

| 49 year | Male | Right | 1st metacarpal | Excision of the tumor with tricortical iliac crest graft |

In 2012, Jin Chang Moon et al. reported a rare case of second metacarpal GCT in a 54-year-old patient, which was managed with chemotherapy with excellent results [17]. In the same year, Keith Jackson et al. reported one case of recurrence of fourth metacarpal GCT after 43 years of initial treatment, representing the versatility of GCT [18].

After curettage followed by autologous bone graft, around 90% of recurrence was reported [3], leading to extensive en-block excision of the tumor as the only option [4]. Procedures like local resection or ray amputation are used to eradicate the disease but long-term follow-up results are still not available in the literature.

Maini et al. tried to preserve the joint function of the fifth metacarpal giant cell tumor; they did en-bloc resection of the tumor with the fifth metacarpal and regained joint function with free osteoarticular metatarsal with the joint capsule, synovium, and ligaments transfer in a single-stage surgery. They hypothesized that the synovial layer of the proximal phalanx provides continuous nutrition to cartilage and metatarsal head, which enhances graft uptake [19].

Patrick S et al. used an autologous tricortical iliac graft after ray amputation of metacarpal giant cell tumor [14]; similarly, Manfrini et al. managed recurrent giant cell tumor by en-block resection and autologous fibula graft with implant arthroplasty at the metacarpophalangeal joint and observed excellent hand function in eight-year follow-up [9]. We reported a rare case of entire first metacarpal GCT in an around 29-year-old female, which was managed with en-block resection of the tumor with interposition of free fibular bone graft and MCP and carpometacarpal joint arthrodesis. This option allowed salvage of the patient’s native thumb with functional use as a stable post, to which she can pinch and grasp objects.

In contrast to implants, heavy plates, and screws interfering with tendon gliding, we could achieve adjacent metacarpophalangeal and carpometacarpal joint fusion with the help of only K wire and supplemented plaster support. We are reporting the case for its size (mammoth), total excision of the thumb metacarpal, fibula graft reconstruction, transarticular K wire arthrodesis, and its rarity.

Conclusions

Giant cell tumor of the metacarpal is a rare type, with rapid progression of signs and symptoms even in young patients. They are osteolytic locally aggressive tumors with a high incidence of metastasis and recurrence. En-bloc resections of tumors with a 1 cm safe margin prevent recurrence in most cases. But the loss of hand function cannot be exigent. We proposed single-stage surgical resection of the first metacarpal and reconstruction by free fibular graft reconstruction. The short-term result is very encouraging with respect to both the function and absence of recurrence and are awaiting long-term follow-up.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Dahlin DC, Unni KK. Vol. 263. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. Dahlin's Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11087 Cases. 5th Ed; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giant cell tumours of the bones of the hand. Averill RM, Smith RJ, Campbell CJ. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-5023(80)80042-6. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(80)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recurrence of giant cell tumors in the hand: a prospective study. Williams J, Hodari A, Janevski P, Siddiqui A. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.12.004. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giant cell bearing lesion of the bone of the hands. Dahlin DC. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-0712(21)00659-4. Hand Clin. 1987;3:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giant cell tumor of the temporal bone - a case report. Pai SB, Lalitha RM, Prasad K, Rao SG, Harish K. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6815-5-8. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2005;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giant cell tumors and aneurysmal bone cysts of spine. Utrecht VH. J Bone Joint Surg. 1965;47:701. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metaphyseal fibrous defects. Betsy M, Kupersmith LM, Springfield DS. https://journals.lww.com/jaaos/Fulltext/2004/03000/Metaphyseal_Fibrous_Defects.4.aspx. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:89–95. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silastic replacement of metacarpal after resection of giant cell tumour. A case report. Chatterjee A, Dholakia DB, Vaidya SV. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHSB.2004.01.007. J Hand Surg Br. 2004;29:402–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fibular autograft and silicone implant arthroplasty after resection of giant cell tumor of the metacarpal—a case report with 9-year follow-up. Manfrini M, Stagni C, Ceruso M, Mercuri M. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016470410004201. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75:779–781. doi: 10.1080/00016470410004201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alternative surgical treatment for giant-cell reparative granuloma in the metacarpal, using phenol and ethanol adjuvant therapy. Yoshida T, Sakamoto A, Tanaka K, Matsuda S, Oda Y, Iwamoto Y. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.001. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32:887–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vascularised joint transfer in the management of recurrent giant cell tumour of the second metacarpal. Kotwal PP, Nagaraj C, Gupta V. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1753193408089048. J Hand Surg Eur. 2008;33:314–316. doi: 10.1177/1753193408089048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giant-cell tumor of the fourth metacarpal bone in children: case report. Arroud M, Afifi MA, Chbani L, Riffi AA, Bouabdallah Y. https://journals.lww.com/jpo-b/toc/2010/01000. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19:86–89. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e328332b8a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giant cell tumour of first metacarpal bone. Shahid M, Varshney M, Maheshwari V, Mubeen A, Gaur K, Siddiqui M. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3687. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:0. doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reconstruction of the second metacarpal bone with a free vascularized scapular bone flap combined with nonvascularized free osteocartilagineous grafts from both second toes: a case report. Jaminet P, Pfau M, Greulich M. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.20826. Microsurgery. 2011;31:146–149. doi: 10.1002/micr.20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An uncommon presentation of giant cell tumor. Al-Kindi H, George M, Malhotra G, Al-Muzahmi K. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22125733/ Oman Med J. 2011;26:359–361. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reconstruction of an entire metacarpal and metacarpophalangeal joint using a fibular osteocutaneous free flap and silicone arthroplasty. Jones NF, Dickinson BP, Hansen SL. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.031. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Multiple pulmonary metastases from giant cell tumor of a hand. Moon JC, Kim SR, Lee YC, Chung MJ. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823483e1. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343:171–173. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823483e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recurrence of a giant cell tumor of the hand after 42 years: case report. Jackson K, Key C, Fontaine M, Pope R. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.12.005. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:783–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer for giant cell tumor of metacarpal—a surgical technique. Maini L, Cheema GS, Yuvarajan P, Gautam VK. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3172360/ J Hand Microsurg. 2011;3:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s12593-011-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Management of giant cell tumor occupying the 5th metacarpal bone in 6 years old child. Al Lahham S, Al Hetmi T, Sharkawy M. https://doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2013.8. Qatar Med J. 2013;2013:38–41. doi: 10.5339/qmj.2013.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Multicentric giant cell tumor of the fourth and fifth metacarpals with lung metastases. Naam NH, Jones SL, Floyd J, Memisoglu EI. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11552-013-9574-x. Hand. 2014;9:389–392. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9574-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reconstruction of an entire thumb metacarpal: a case report. Lim S, Babineaux KL. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:0. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Functional reconstruction of the entire fifth metacarpal bone after en-bloc resection with a Y-shaped bone fusion to the fourth metacarpal: a case report. Bergmeister KD, Kneser U, Bickert B. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1753193417701061. J Hand Surg Eur. 2017;42:970–971. doi: 10.1177/1753193417701061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The giant cell tumour of the proximal phalanx of the thumb treated by a 2-stage operation. Reichert P, Kowalski P, Gosk J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aott.2017.03.015. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2017;51:425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.aott.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.A patient-matched entire first metacarpal prosthesis in treatment of giant cell tumor of bone. Punyaratabandhu T, Lohwongwatana B, Puncreobutr C, Kosiyatrakul A, Veerapan P, Luenam S. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4101346. Case Rep Orthop. 2017;2017:4101346. doi: 10.1155/2017/4101346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giant cell tumor of the metacarpal: case report. Lewallen LW, Wagner ER, Moran SL. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1558944717697431. Hand. 2017;12:0–7. doi: 10.1177/1558944717697431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giant-cell tumor of metacarpal in the skeletally immature patient and free osteoarticular metatarsal transfer: review of literature with case report. Mishra PK, Agarwal Y, Singhal P, Mishra KS. https://dx.doi.org/10.13107%2Fjocr.2250-0685.880. J Orthop Case Rep. 2017;7:20–23. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Third-ray and capitate resection with limited midcarpal fusion for recurrent giant cell tumor: a case report. Bokemper MK, Araiza ET, Templeton KJ, Fox TJ. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29538093/ JBJS Case Connect. 20181;8:0. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.CC.17.00161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giant cell tumor of the metacarpal bones. Saikia KC, Bhuyan SK, Ahmed F, Chanda D. Indian J Orthop. 2011;45:475–478. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.83957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]