Abstract

The postpartum period represents a critical window of opportunity to improve maternal short- and long-term health, including optimizing postpartum recovery, providing effective contraception, caring for mood disorders, managing weight, supporting lactation, initiating preventive care, and promoting cardiometabolic health. However, inadequate postpartum care, especially for individuals facing social and structural barriers, is common in the United States and contributes to suboptimal health outcomes with lasting consequences.

Patient navigation is a patient-centered intervention that uses trained personnel to identify financial, cultural, logistical, and educational obstacles to effective health care, and to mitigate these barriers in order to facilitate comprehensive and timely access to needed health services. Given emerging evidence suggesting patient navigation may be a promising method to improve health among postpartum individuals, our team developed a postpartum patient navigator training guide to be used in the Navigating New Motherhood 2 (NNM2) and other obstetric navigation programs. NNM2 is a randomized trial exploring whether patient navigation by a trained, lay postpartum navigator for low-income individuals can improve health and patient-reported outcomes during and after the postpartum period. Hiring and training patient navigators without health professional degrees are integral components of initiating a navigation program. Yet, patient navigator training is highly variable, and no guidelines regarding key elements in such a training program exist for obstetrics specifically.

Thus, this paper aims to describe the core principles, content, and rationale for each element in a comprehensive postpartum patient navigator training program. Training should be centered around six core elements: 1) principles of patient navigation, 2) knowledge of pregnancy and postpartum care, 3) health education and health promotion principles, 4) cultural sensitivity and health equity, 5) care coordination and community resources, and 6) electronic medical record systems. These core elements can serve as a basis for the development of adaptable curricula for a variety of institutions and contexts. We also offer recommendations for the implementation of a navigator training program. A curriculum such as this, with built-in flexibility to meet community and institutional needs, may promote the effective and sustainable use of patient navigation in the postpartum context.

Keywords: health disparities, health education, patient navigation, patient navigator, postpartum, navigator training

CONDENSATION

We describe core principles and training practices to equip postpartum patient navigators with the skillset to guide patients through the postpartum period.

I. INTRODUCTION

The postpartum period represents a critical opportunity to improve short- and long-term health. The first months after birth are a time of remarkable change and vulnerability in an individual’s physical health, psychological well-being, and social roles. The postpartum period is unique because pregnancy serves as a window to future health,1–5 and can be a period of enhanced access to health care.4,5 Individuals interact with the healthcare system more frequently during the prenatal period, and the availability of publicly funded care for low-income pregnant individuals facilitates enhanced access to care. Patients are additionally motivated to improve health behaviors during pregnancy,6–9 and thus this period has the potential to spark lifelong changes.10,11 Optimizing pregnancy-specific health status, providing postpartum care for chronic comorbidities, and promoting changes in health behaviors in the postpartum period may positively influence lifelong health.

Yet, engagement in postpartum care in the United States (US) is suboptimal, and improving health after pregnancy requires novel and comprehensive approaches to postpartum care and health care transitions. Our team previously demonstrated that the introduction of a postpartum patient navigator to an obstetric practice was associated with improvements in health metrics compared to a historical cohort who did not have access to navigation.12 Following those findings, we are determining whether patient navigation improves short- and long-term health via the Navigating New Motherhood 2 (NNM2) trial, in which publicly insured low-income pregnant and postpartum individuals are randomized to receive either navigation or usual care during the first year after birth (NCT0392233413). For participants randomized to receive navigation, a postpartum patient navigator provides intensive, individualized, one-on-one navigation services.

However, there is no current template for the core principles or training elements for postpartum patient navigators. Thus, we developed and implemented a comprehensive curriculum to train patient navigators for the trial, but also for postpartum navigation in general. To develop this training program, we referenced multiple sources, including existing literature about postpartum care and navigation in other contexts, our experience as health services and obstetrics experts, the experience of clinical team members with the prior navigation program,14 and the input of the navigators themselves. Although the NNM2 trial is ongoing and results are not yet available, the concept of patient navigation is of increasing interest in obstetrics, and we believe our experience with developing a postpartum navigator training program may be useful to clinicians, researchers, and quality improvement experts looking to design similar programs in their own context.

The objectives of this manuscript are to describe the rationale for postpartum patient navigation; review the training goals, methods, and principles of a navigation program; delineate a blueprint for the translation of principles to practice; and provide recommendations for programmatic development.

II. RATIONALE FOR POSTPARTUM PATIENT NAVIGATION

Although the postpartum period represents a critical opportunity for engagement with medical care, uptake of postpartum care in the US is often poor. As many as 40% of individuals do not attend a postpartum healthcare visit.15,16 Socioeconomic inequities in postpartum care are abundant16–21 and ample evidence identifies that there are multiple barriers to care, including potentially lesser prioritization of maternal care compared to pediatric care.22–26 Even when care is received, care quality may be suboptimal.27,28 Furthermore, the transition to primary care commonly does not occur.4,16,23 Thus, the postpartum period represents a critical window for retention in high quality health care and a clear gap in the current health system; this gap is even wider for those with inadequate insurance coverage, cultural or linguistic barriers to health care, limited health literacy, who live in rural areas or inaccessible urban areas, or who have other challenges to accessing health during this transitional period.

Patient navigation is a patient-centered intervention utilizing trained non-medical personnel to identify financial, cultural, logistical, educational, and other obstacles to health care, and then to mitigate these barriers by facilitating comprehensive and timely access to health services.29 The core principles of navigation involve identifying patient- and system-level barriers to access, improving timeliness of care, providing health education, and offering social support.30–32 In the postpartum period, the broad goals of a postpartum patient navigation program are to improve health by 1) increasing the receipt of postpartum care in the indicated time periods by reducing barriers to accessing and engaging with health care, 2) improving the quality of postpartum patient care by equipping patients with tools for self-advocacy and providing health education, and 3) ensuring comprehensive transitions from obstetric care to primary care. Postpartum-specific goals that may serve as guideposts for patient navigation programs include attendance at a comprehensive postpartum appointment, receipt of postpartum-specific anticipatory guidance, receipt of desired contraception, initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding when desired, receipt of indicated screening (such as for perinatal depression), and receipt of preventive care and indicated screening (such as blood pressure, weight, and metabolic tests).33

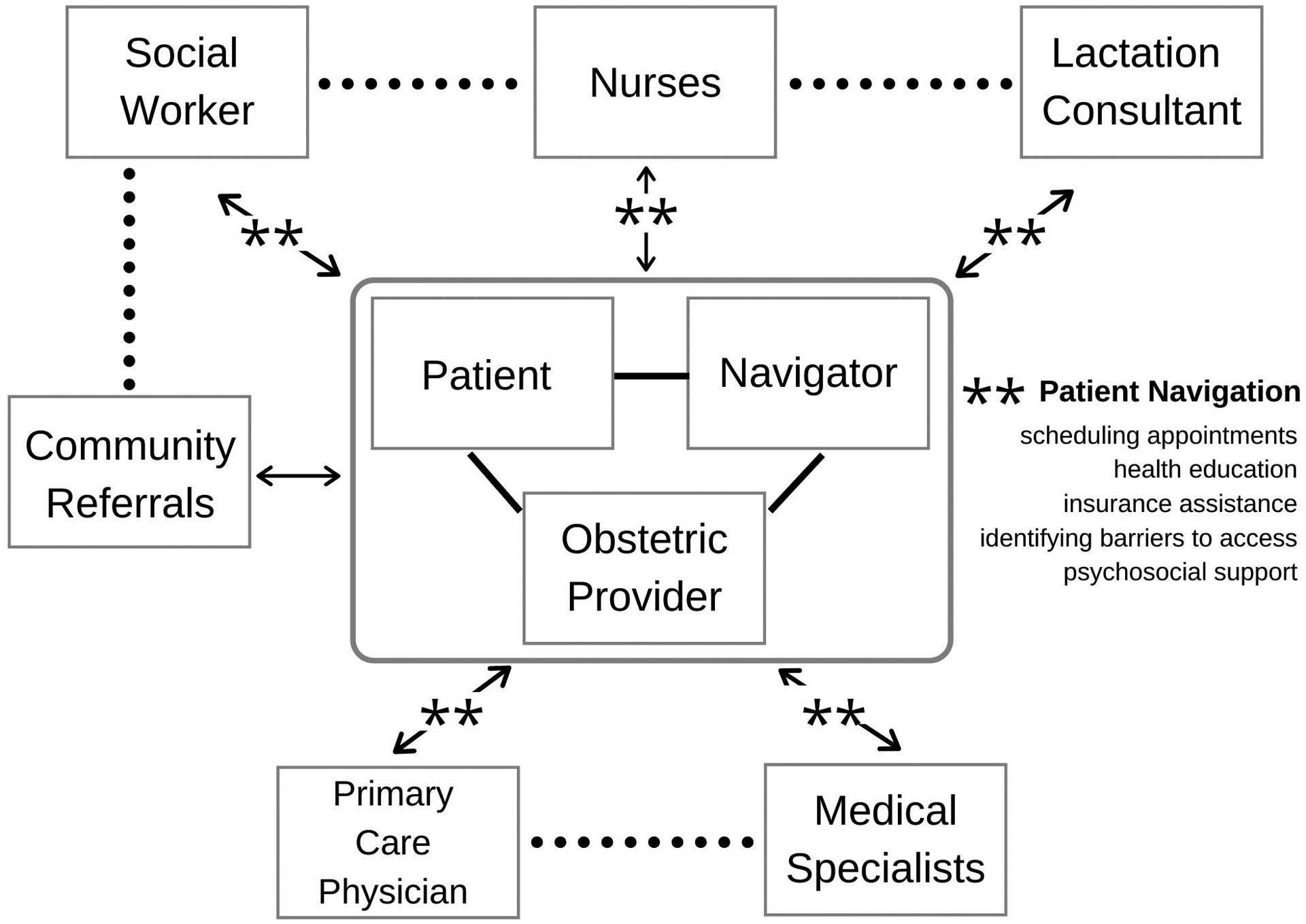

To achieve these aims, navigators perform many duties, including arranging transportation, completing documentation, helping patients understand and utilize insurance coverage, helping patients obtain health information, providing psychosocial support, assisting patient-provider communication, encouraging patient activation, and linking patients to community resources (Figure 1).30,34 As a longstanding component of oncology care and a growing element in chronic disease management, patient navigation has consistently been shown to improve patient outcomes and reduce disparities in both healthcare access and health outcomes.30,31,34–45

Figure 1:

Patient navigation: Bridging gaps across systems of care

** indicates bidirectional navigation

Although navigation aims to address specific episodes of patients’ needs, it has the potential to promote the self-efficacy, system awareness, and health literacy skills necessary for patients to become fully activated participants in health care long after the navigation partnership concludes.29 Based on the compelling evidence for patient navigation as a barrier-reducing strategy in other health domains, we proposed that navigation could be a viable method to address gaps in postpartum care for vulnerable populations in the US.13

III. TRAINING OVERVIEW

III.1. Training Goals

Navigators come from diverse backgrounds with variable degrees of formal training and professional experience.29 There are established benefits of training individuals who are not health care professionals to be patient navigators, and evidence from oncology suggests that, with proper training, a lay navigator can develop the skills to support complex care needs.46 However, no current guidelines for obstetric or postpartum navigation training exist. In other fields, common topics of navigation curricula include communication skills, cultural competence, barriers to care, specific health education topics, and resources unique to the locality.47–49 Because of the novel application of patient navigation to postpartum care, we adapted these topics and skills in order to develop a postpartum navigator training program.

First, based on our experience and review of the existing literature, we identified key characteristics of a postpartum navigator, including strong communication skills, a relationship-building capacity, problem-solving skills, knowledge about prenatal and postpartum care, and a capacity to understand the health care system. Second, we delineated six core elements for navigator professional development: 1) principles of patient navigation, 2) knowledge of prenatal and postpartum care, 3) health education and health promotion principles, 4) cultural sensitivity and health equity, 5) care coordination and community resources, and 6) electronic medical record (EMR) systems (Table 1). These principles are the framework for the navigator training program.

Table 1:

Core elements for obstetric navigator professional development

| Core Elements for Obstetric and Postpartum Navigator Professional Development |

|---|

| Principles of Patient Navigation |

| Knowledge of Prenatal and Postpartum Care |

| Health Education and Health Promotion Principles |

| Cultural Sensitivity and Health Equity |

| Care Coordination and Community Resources |

| Electronic Medical Record Systems |

III.2. Training Methods

We designed a comprehensive, semi-structured training plan to develop foundational knowledge and skills for the patient navigator role. The curriculum was designed to encompass the six core principles using a multimodal educational approach combining experiential and self-directed training. To design this curriculum, we outlined the care processes and potential issues an individual may experience throughout pregnancy, delivery, the early postpartum period, and the transitional period during the first postpartum year, especially as related to accessing healthcare. We accomplished this process via evaluating our experiences with prior navigation programs, as clinicians and other care team members, and by discussions with postpartum individuals. Although there is significant variability in patients’ needs, this process mapping effort focused the training so a navigator could understand the spectrum of health care and the psychosocial complexity during this life stage.

After identifying these touchpoints, we leveraged the expertise of multiple clinical care team members to create a multi-pronged educational approach. The training period consisted of eight weeks of learning and preparatory work, including a four-week period of observational and experiential learning (Table 2). We included formal didactic methods, such as structured courses, self-directed readings, webinars, and lectures (Table 3). This flexible curriculum was intended to promote development of the core principles in an interactive manner that allowed for skills-building and led to an intimate familiarity with local resources. This length of time was selected in order to quickly acclimate the navigators to their roles via this intensive training period, which was then followed by ongoing learning while in the navigator role.

Table 2.

Navigator experiential training overview

| Content | Learning Strategy | Key Learning Points | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient setting | |||

| Obstetrical triage | Observing triage physician director |

|

2 hours |

| Emergency department | Orienting with resident in obstetrics and gynecology |

|

1 hour |

| Labor and delivery | Orienting to labor and delivery |

|

4 hours |

| Postpartum care | Observing nurses on postpartum mother-baby units |

|

4 hours |

| Lactation support | Shadowing lactation consultants |

|

4 hours |

| Inpatient social work | Shadowing inpatient women’s health Licensed Clinical Social Worker |

|

4 hours |

| Neonatal care | Shadowing NICU social workers |

|

3 hours |

| Obstetric outpatient setting | |||

| Outpatient clinic operations | Meeting with the Practice Manager |

|

1 hour |

| Patient registration and scheduling | Meeting with Patient Service Representative |

|

3 hours |

| Patient intake for physician appointment | Shadowing Medical Assistant (MA) and introduction with lead MA |

|

4 hours |

| Physician role in antenatal care | Shadowing obstetrician-gynecologist physicians |

|

8 hours |

| Subspecialist role in obstetric care | Shadowing MFM physicians and MFM New Patient Liaison |

|

6 hours |

| Nurse role in antenatal and postpartum care | Shadowing nurses during provision of antenatal and postpartum care |

|

4 hours |

| Lactation support | Clinic interaction with Lactation Peer Counselor |

|

2 hours |

| Nutrition for pregnancy and postpartum | Shadowing Registered Dietitian |

|

3 hours |

| Care needs of pregnant patients with diabetes | Shadowing diabetes Advanced Practice Nurse |

|

4 hours |

| Outpatient social work | Shadowing outpatient women’s health and fetal health Licensed Clinical Social Workers |

|

1 day |

| Perinatal mental health care | Meeting with perinatal mental health Licensed Clinical Social Worker |

|

2 hours |

| Gestational weight gain and postpartum weight loss | Training with an MFM expert in obesity and weight |

|

1 hour |

| Perinatal loss | Meeting with perinatal loss Licensed Clinical Social Worker |

|

1 hour |

| Overview of patient navigator role and daily activities | Shadowing breast oncology nurse navigator |

|

3 hours |

| Primary care outpatient setting | |||

| Primary care | Shadowing primary care physicians in a women’s health-focused primary care practice |

|

4 hours |

| Primary care patient care coordinator | Meeting with practice coordinator for a primary care practice |

|

1 hour |

| Health systems resources and electronic medical record | |||

| Hospital resources | Tour of physical facility |

|

3 hours |

| Health education | Orienting at the Health Learning Center |

|

1 hour |

| Hospital Crisis Intervention Program | Meeting with Domestic Violence Program Counselor |

|

1 hour |

| Patient Innovation Center | Meeting with Executive Director |

|

2 hours |

| Change Health (Medicaid representative) | Meeting with Manager and Field Services Representative |

|

2 hours |

| Patient Relations and Medical Records | Meeting with representatives from the patient relations and medical records offices |

|

1 hour |

| Documentation, tracking, and messaging in the EMR | Meeting with outpatient Resource Coordinator |

|

3 hours |

| Scheduling and clinical uses of the EMR | EMR training course |

|

2 days |

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit

MFM, maternal fetal medicine

EMR, electronic medical record

Table 3.

Didactic Training for Patient Navigators

| Content | Source | Key Learning Points |

|---|---|---|

| Formal Training Courses | ||

| Fundamentals of Patient Navigation (8 week course)52 | Patient Navigator Training Collaborative (PNTC) course |

|

| Care Coordination Course (4 week course)51 | PNTC course |

|

| Introduction to Chronic Disease54 | PNTC course |

|

| Introduction to Healthcare System55 | PNTC course |

|

| Preventive Healthcare 10156 | PNTC course |

|

| Motivational Interviewing57 | PNTC course |

|

| Readings | ||

| Patient Navigation: Overcoming Barriers to Care46 | Textbook |

|

| National Navigation Roundtable (NNRT) materials58 | NNRT |

|

| Motivational Interviewing59 | ACOG |

|

| Benefits to Women of Medicaid Expansion Through the Affordable Care Act60 | ACOG |

|

| Breastfeeding in Underserved Women61 | ACOG |

|

| Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding (ACOG Breastfeeding Toolkit)62 | ACOG |

|

| Healthcare for Homeless Women63 | ACOG |

|

| Challenges for Overweight and Obese Women64 | ACOG |

|

| Access to Contraception65 | ACOG |

|

| Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception66 | ACOG |

|

| Bedsider Birth Control Support Network67 | Website |

|

| Health Literacy to Promote Quality of Care68 | ACOG |

|

| Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology69 | ACOG |

|

| Health Care for Unauthorized Immigrants70 | ACOG |

|

| Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Awareness in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care71 | ACOG |

|

| Health Disparities in Rural Women72 and Providing Safe, High-Quality Maternity Care in Rural US Hospitals73 | ACOG and Institute for Healthcare Improvement |

|

| Implicit Bias in Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review74 | Article |

|

| Optimizing Postpartum Care15 | ACOG |

|

| Screening for Perinatal Depression75 | ACOG |

|

| Expression of Emotion Through Nonverbal Behavior in Medical Visits76 | Article |

|

| Project Implicit77 | Project Implicit |

|

| Webinars | ||

| Managing difficult encounters78 | PNTC Webinar |

|

| LGBTQ Cultural Responsiveness79 | PNTC Webinar |

|

| Seminar on Poverty and Self-Sufficiency80 | PNTC Webinar |

|

| Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services Standards for Navigators81 | PNTC Webinar |

|

| Basic Crisis Management Skills for Patient Navigators82 | PNTC Webinar |

|

| Healthier Pregnancy Interventions to Promote Breastfeeding83 |

ACOG |

|

| Maintaining Breastfeeding beyond the First Week84 | ACOG |

|

| Implicit Bias Video Series85 | UCLA Know Implicit Bias Series |

|

| Grand Rounds and other in-person lectures | ||

| Bipolar Disorder in the Perinatal Patient | Lecture |

|

| Housing as a Structural Determinant of Perinatal Health | Lecture |

|

| Perinatal Depression Screening and Treatment | Lecture |

|

| Gestational Diabetes Mellitus | Lecture |

|

ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

III.3. Observational and Experiential Learning

Observational learning is an integral component of navigator training. We designed the observational and experiential learning schedule to orient the navigators to the obstetric and postpartum inpatient and outpatient care teams as well as community and institutional resources. We aimed to expose the navigators to all care team members with whom a patient could potentially interact during the late antenatal and postpartum period. Each care team member (Table 2) offered a detailed understanding of their role and how it may intersect with a navigator while providing patient care. Navigators subsequently observed staff members performing their regular duties for a time period determined by the level of interaction required and proximity of their role to the navigator. In addition to becoming familiar with various resources, this process allowed the navigators to develop independent relationships with healthcare providers. By introducing the navigator role and explaining the program, this learning period aimed to reduce health system fragmentation for individuals.

The experiential learning phase first included orientation to the inpatient units. Navigators oriented to the locations, roles, and processes of Obstetrical Triage and the Emergency Department, the first units a patient encounters upon admission. They shadowed on the Labor and Delivery unit, and, with patient consent, witnessed birth in order to gain perspective on the labor process and steps involved in a hospital birth. They underwent observational training on the postpartum inpatient units with physicians, nurse managers, and bedside nurses to understand postpartum care processes and inpatient operations. Additionally, the navigators shadowed and had orientations with lactation counselors, inpatient women’s health social workers, and neonatal intensive care unit social workers to understand their roles and routines.

The outpatient observational learning process included orientation to both antenatal and postpartum care (Table 2). The navigators met and observed all team members with whom patients may interact, including medical assistants, registered nurses, social workers, breastfeeding peer counselors, physicians at multiple career stages, patient services representatives, and clinic administrative staff. The goals of this observational process were to identify how best to assist and prepare patients for outpatient care and to understand how navigation supports the roles of these team members. In addition to the care teams available to all patients, navigators observed a diabetes-focused Advanced Practice Nurse, Registered Dietitian, and social workers specific to our institution’s programs (mental health, perinatal loss, and fetal health). The navigators underwent one-on-one training with a maternal-fetal medicine expert in obesity and weight loss. Additionally, the navigators observed a nurse navigator in breast oncology to gain further familiarity with navigation itself. The navigators also engaged in observational learning with primary care providers to develop the skills to promote the transition to primary care. By observing primary care visits and orienting with the clinic’s care coordinator, the navigators developed an understanding of the transition process and primary care resources.

Finally, the navigators underwent health systems observational learning. This included a tour of the patient-facing and non-patient-facing aspects of the hospital campus and meeting with the clinic resource coordinator to understand issues such as scheduling, clinic templates, and administrative resources. The training also included meeting insurance administrators for the health care system, observing the provision of care via this system’s health education specialists, meeting with counselors in the hospital domestic violence crisis program, and learning about the work of the patient relations and medical records offices. Extensive training with the EMR system included learning about documentation, messaging, clinical reports, and scheduling.

IV. TRAINING FOR THE CORE ELEMENTS OF NAVIGATOR DEVELOPMENT

IV.1. Principles of Patient Navigation

Our training developed the navigators’ understanding of the scope and practice of navigation work (Table 3). To accomplish training on the fundamentals of navigation, we utilized the Patient Navigator Training Collaborative (PNTC),50 an established patient navigator training program. The navigators completed the PNTC Fundamentals of Navigation course, an 8-week online training covering several topics: the history of patient navigation, the role of patient navigators, communication, health literacy, health disparities, barrier and needs assessment, problem-solving strategies, motivational interviewing, and professional boundaries. Through this course, navigators developed a foundational understanding of their role and responsibilities, including how to distinguish themselves from other members of the healthcare team. Additionally, the PNTC program offers several skills-building courses that serve as continuing education for navigators, such as the 4-week Care Coordination course.

Training on the principles of patient navigation, professionalism, and communication continued via self-directed didactic materials (Table 3), including the Patient Navigation: Overcoming Barriers to Care textbook, materials from the National Navigation Roundtable, and published works by our own group.12,29,46

Developing professional communication skills is a key requirement of training patient navigators, including maintaining professional boundaries while promoting patient engagement. At our site, navigators employ multiple modes of communication, including email and text-messaging along with in-person visits, to interact with patients. The use of mobile health technology allows patients to easily access navigators but also requires the establishment of a professional navigator-patient relationship to ensure appropriate behavior and effective communication between both parties. Thus, training included discussion of appropriate use of work-issued mobile phones and hours for communication, the use of an on-call system for patients who deliver on weekends, and the development of an emergency protocol for managing urgent needs (such as severe hypertension or suicidality). Via didactic training, role-playing, observation of the navigators with patients, and guidance from navigators in other fields, the training on core principles of navigation aimed to promote professional, balanced communication between patients and team members.

IV.2. Knowledge of Prenatal and Postpartum Care

Although navigators have non-medical professional backgrounds, their role requires basic knowledge of prenatal and postpartum care in order to support patients. Training in these topics largely occurred via the observational and experiential learning processes to orient the navigators to the evolution of healthcare needs throughout the prenatal and postpartum periods. For example, individuals in the late third trimester may need additional logistical support for tasks such as registering at the hospital for delivery, ordering a breast pump, or preparing for hospital visitor policies. In contrast, postpartum care may evolve to include a greater need for community resources or postpartum mental health support.

Although the hospital staff may support some of these tasks, the role of the navigator includes promoting self-advocacy skills needed for patients to realize specific needs and utilize available resources effectively, as well as working with team members to address individual-level barriers. This fundamental perspective differentiates patient navigators from other care team members, who may not approach their roles with the explicit goal of promoting patient activation for long-term success. Patient navigators must be trained to promote activation in the patient’s own healthcare engagement alongside developing skills to succeed in the healthcare system on their own when navigation ends. Dedicated training regarding barrier-reducing support tasks with the evolution of changing needs of pregnancy and postpartum care is essential to achieve the goals of individualized navigation.

IV.3. Health Education and Health Promotion Principles

The third core principle of navigator development includes understanding the goals of health education and health promotion as related to pregnancy and postpartum health. The navigators were expected to develop a basic working knowledge of anticipated health needs of postpartum patients. However, as the navigators are not clinicians, their training also emphasized that they were not expected to provide clinical care or answer clinical questions beyond routine health education, but included resources for redirecting such needs to appropriate clinical personnel.

To organize this learning, didactic training was concentrated on five focal topics the navigators would cover with patients: breastfeeding, contraception and pregnancy spacing, weight loss and metabolic health, mental health transitions and risks, and primary care recommendations and goals (Table 4). The navigators learned about these health education topics by shadowing the health care team, attending lectures and webinars, and reading materials from professional societies (Table 3). Table 3 reflects the health education learning tools used specifically for this program, although we acknowledge that materials from other sources or professional societies may provide similar content with additional perspectives.

Table 4:

Example education resources by focal area

| Focal area | Example Educational Resources |

|---|---|

| Infant feeding |

|

| Contraception and pregnancy spacing | |

| Weight loss and promotion of metabolic health |

|

| Mental health transitions and risks |

|

| Primary care |

|

| Health disparities and health services |

|

Health promotion concepts were addressed via training in motivational interviewing, which offered strategies for discussing difficult topics or health issues requiring patients to have a more active role. Because navigators aim to improve patient health outcomes by supporting self-efficacy, high-quality motivational interviewing is a valuable tool. In addition to didactic material, we addressed this skill via one-on-one demonstration and simulation opportunities using standardized clinical scenarios. Care team members provided in-person training on health promotion by demonstrating motivational interviewing in practice and sharing the health resources they provide to patients. The curriculum’s combined focus on topical knowledge and health promotion techniques equipped navigators to provide patients with accurate information.

IV.4. Cultural Sensitivity and Health Equity

Patient navigation is often designed to support diverse, low-income, and/or under-resourced populations. Thus, we included training in the concepts of health equity, health disparities, and social determinants of health. Many barriers to optimal postpartum care exist, including knowledge and lack of awareness of need, insurance coverage, childcare, adequate access to food and other necessary resources, early return to work, linguistic barriers, poor provider continuity, transportation, and many others. Training on the patient- and healthcare system-based social determinants and equity issues was accomplished via in-person discussions with the team, self-directed readings on social determinants, and lectures and webinars highlighting aspects of care for different sociodemographic groups and advocacy skills (Table 3). Training emphasized a culturally sensitive, holistic approach to patient care, with emphasis on openness and appreciation for the diverse perspectives of the patient population. While navigators are not expected to be intimately familiar with the cultural background of all patients, they must demonstrate compassion and understanding in order to engage effectively and equitably with patients and advocate appropriately on their behalf. Navigators, who were bilingual English- and Spanish-speakers, were also trained in the professional provision of bilingual navigation services.

Additionally, navigator training must expose navigators to the challenges within the healthcare system that disadvantage certain groups, including issues of racism and implicit bias. The curriculum aimed to offer insight on the issues patients may face, including discrimination and stigma due to racial or ethnic identity or other issues such as mental health, obesity, or socioeconomic status, when accessing care. Our didactic library further addressed intersectional topics, such as health literacy, healthcare for individuals with housing instability, and health for sexual and gender minority individuals. The navigator training includes didactic and experiential learning with querying patients about their social determinants of health and then specifically providing resources tailored to each individuals’ needs; for example, navigators learn how to sensitively determine if a barrier such as insurance coverage is prohibiting her from accessing her desired contraceptive method followed by working with the patient to resolve the gaps in coverage or identify other resources to fulfill this need.

IV.5. Care Coordination and Community Resources

Integration of navigators into care teams is essential to the successful implementation of navigation programs. Thus, training included introducing the clinical team to the program objectives and the navigators’ role. Navigators regularly coordinate with other care team members to support patients. As such, relationships between navigators and care team members facilitate effective healthcare access for patients. Training in team-based care was accomplished via meetings with the clinical team (Table 2) and the formal courses described above (Table 3), which emphasized team-based care coordination with a patient-centered approach.51,52 Navigators learned communication techniques to help with team collaboration, reduce fragmentation in care, and promote accountability to a shared care plan.

In addition to coordinating patient care within the hospital system, navigators are expected to facilitate patient access to community resources, including community-based care coordination or community navigation programs. Such support includes developing a catalog of institutional, community health, and social services available to patients that cater to various backgrounds and communities. Thus, training included acquiring familiarity with such resources, via guidance from social workers and self-directed resource searching, in order to coordinate care and connect patients to services. Training additionally included learning of the scope of practice of community resources and developing the communication skills to enhance partnerships with community resources and to optimize the hand-offs from the healthcare system to the community.

Training in community resources extended beyond the initial 8-week period, given the depth and breadth of resources available in this large metropolitan area. Once navigators developed connections with their patients and identified individual needs, they were provided additional training in specific areas. Two such areas for inclusion in navigator curricula include public insurance and housing resources. The complexity of the public insurance system requires intimate familiarity with insurance options, as navigators commonly spend extensive time supporting insurance issues in the transition period after birth. Similarly, housing stability plays an important role in healthcare access and utilization. Training on housing programs and coordination of efforts with social workers is a critical component of community resource training, and navigator training that includes familiarity with such community resources can be a major benefit to patients.

IV.6. Electronic Medical Record Systems

Lastly, navigators must have access to and facility with the institution’s EMR system to coordinate care and communicate with patients’ care teams. The EMR system allows the team to document and communicate patient care and treatment plans. Access to and documenting within the EMR allows navigators to actively engage with the care team, schedule appointments, and integrate their work into patient care.

Several phases of work prepared the navigators to utilize the EMR system. First, information technology, security, and legal agreements established navigators’ terms of usage, access and functional privileges with regard to scheduling, messaging, and documentation. Second, a two-day training course offered an overview of our hospital’s EMR system and a detailed experiential learning process regarding EMR-specific skills. This course included learning how to schedule appointments and developing skills to use the EMR independently. Third, navigators worked with clinical team members to better understand their roles in clinical documentation. Clinic administrative staff provided a step-by-step instructional guide and demonstrations in real-time settings. Finally, our team built EMR system templates for the navigator role, which required advanced understanding of EMR-specific processes and confidentiality safeguards for EMR patient information. Upon completion of this EMR training, the navigators were able to independently conduct all functions necessary for their role.

V. RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The training of a postpartum patient navigator requires the development of a myriad of skills and a broad knowledge base to optimally support the postpartum health of diverse populations. To accomplish these goals, we identified key recommendations:

Ensure training is flexible and adaptable to local needs while also centering the curriculum on the core professional development elements.

When orienting institutional and community members who will interact with the navigators, fully introduce the navigator role and the purpose of the program to reduce confusion and promote collaboration among all team members.

Seek input from clinical and administrative stakeholders about critical topics to include throughout training.

Standardize and clarify expectations for the outcomes of navigator training to ensure adequate incorporation of content and skills.

Explain and reinforce the program goals and navigator scope with the clinical care team to align expectations and promote integration.

Incorporate clinical team feedback in identifying priority areas for ongoing navigator education.

Identify the ongoing needs of navigators after initiation of their role. Periodically query the navigators regarding knowledge gaps as their roles evolve.

Develop a plan for “Continuing Navigator Education.” Ongoing professional development may take place at a standard time (e.g., every six months) via formal lectures, webinars, or readings.

However, despite these key recommendations for the optimization of a patient navigator training program, the development and sustainability of patient navigator programs are not without challenges. Educating clinical stakeholders to understand the navigator role and engaging them to partner with navigators require a dedicated and cohesive leadership team and ongoing systems for feedback and programmatic modifications.46,53 Since patient navigation is not yet a standard, reimbursable service in obstetrics, funding for patient navigators often comes from research or philanthropy.53 Future work must consider not only the efficacy of patient navigation to improve health but also its cost-effectiveness in order to support the need for insurers to pay for navigation programs. In addition, challenges with delineating the scope of practice may exist; navigation programs need clear goals and context-specific scope of practice definitions in order to function most effectively.46 Finally, optimizing implementation of navigation programs requires not just commitment to the training of a navigator, but also ongoing program evaluation in order to ensure scalability and sustainability within a given healthcare setting.

We propose that patient navigation may be an effective approach to improve postpartum health and reduce inequities. This adaptable blueprint for training an obstetric and/or postpartum navigator may be readily tailored to fit the needs of institutions, while centering on core competencies for the role. This multimodal training method is a practical way for navigators to learn and engage with a variety of courses, individuals, and materials.

FUNDING:

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development R01 HD098178. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roberts J, Hubel C. Pregnancy: A screening test for later life cardiovascular diseases. Women’s Health Issues 2010;20:304–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunderson E, Chiang V, Pletcher M, et al. History of gestational diabetes mellitus and future risk of atherosclerosis in mid-life: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauspurg A, Ying W, Hubel C, Michos E, Ouyang P. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and future maternal cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiology 2018;41:239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta P, Minissian M, Merz C. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular risk factor management. Semin Perinatol 2015;39:268–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SMFM White Paper: Pregnancy as a Window to Future Health:. 2015. (Accessed October 27, 2016, at www.smfm.org/publications/141-smfm-white-paper-pregnancy-as-a-window-to-future-health.)

- 6.Yee LM, Simon M, Grobman W, Rajan P. Pregnancy as a “golden opportunity” for patient activation and engagement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2009;3:CD001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2013;10:CD001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsen P Brief alcohol intervention to prevent drinking during pregnancy: an overview of research findings. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2009;21:496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kershaw TS, Magriples U, Westdahl C, Rising SS, Ickovics J. Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care. Am J Public Health 2009;99:2079–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magriples U, Boynton MH, Kershaw TS, et al. The impact of group prenatal care on pregnancy and postpartum weight trajectories. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:688 e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yee LM, Martinez NG, Nguyen AT, Hajjar N, Chen MJ, Simon MA. Using a Patient Navigator to Improve Postpartum Care in an Urban Women’s Health Clinic. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:925–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navigating New Motherhood 2: NCT03922334. 2020. (Accessed August 24, 2020, at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03922334?term=lynn+yee&draw=1&rank=2.)

- 14.Hu F, Strohbach A, Martinez NG, Hajjar N, Simon M, Yee LM. Patient and provider evaluation of a postpartum patient navigation program to improve postpartum care among publicly insured women. Am J Perinatol 2019;E-pub ahead of print; doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1696671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett W, Chang H, Levine D, et al. Utilization of primary and obstetric care after medically complicated pregnancies: an analysis of medical claims data. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:636–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant A, Haas J, McElrath T, McCormick M. Predictors of compliance with the postpartum visit among women living in Healthy Start project areas. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:511–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rankin K, Haider S, Caskey R, Chakraborty A, Roesch P, Handler A. Healthcare utilization in the postpartum period among Illinois women with Medicaid paid claims for delivery, 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:144–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilcox A, Levi EE, Garrett JM. Predictors of Non-Attendance to the Postpartum Follow-up Visit. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu M, Prentice J. The postpartum visit: Risk factors for nonuse and association with breastfeeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:1329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiBari J, Yu S, Chao S, Lu M. Use of postpartum care: Predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy 2014;530769:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aber C, Weiss M, Fawcett J. Contemporary women’s adaptation to motherhood: the first 3 to 6 weeks postpartum. Nurs Sci Q 2013;26:344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett W, Ennen C, Carrese J, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of postpartum follow-up care in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:239–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin A, Horowitz C, Balbierz A, Howell E. Views of women and clinicians on postpartum preparation and recovery. Maternal Child Health J 2014;18:707–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Negron R, Martin A, Almoq M, Balbierz A, Howell E. Social support during the postpartum period: mothers’ views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:616–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slomian J, Emonts P, Vigneron L, et al. Identifying maternal needs following childbirth: A qualitative study among mothers, fathers and professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeClerq E, Sakala C, Corry M, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Listening to Mothers III: New Mothers Speak Out. New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howell E Lack of patient preparation for the postpartum period and patients’ satisfaction with their obstetric clinicians. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenney K, Martinez NG, Yee LM. Patient navigation across the spectrum of women’s health care in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Report to Congress: Patient Navigator Outreach and Chronic Disease Prevention Program, FY 2008–2012: Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells K, Battaglia T, Dudley D, et al. Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science? Cancer 2008;113:1999–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glanz K, RImer B, Viswanath K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice (5th Edition). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Optimizing Postpartum Care, Committee Opinion No. 666. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016;127:e187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:237–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice K, Gressard L, DeGroff A, et al. Increasing colonoscopy screening in disparate populations: Results from an evaluation of patient navigation in the New Hampshire Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Cancer 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer SM, Cervantes L, Fink RM, Kutner JS. Apoyo con Carino: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latinos with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:657–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ko NY, Snyder FR, Raich PC, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient navigation: Results from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer 2016;122:2715–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genoff M, Zaballa A, Gany F, et al. Navigating language barriers: A systematic review of patient navigators’ impact on cancer screening for limited English proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:426–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: the Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luckett R, Pena N, Vitonis A, Bernstein MR, Feldman S. Effect of patient navigator program on no-show rates at an academic referral colposcopy clinic. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeGroff A, Schroy PC 3rd, Morrissey KG, et al. Patient Navigation for Colonoscopy Completion: Results of an RCT. American journal of preventive medicine 2017;53:363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jean-Pierre P, Cheng Y, Wells K, et al. Satisfaction with cancer care among underserved racial-ethnic minorities and lower-income patients receiving patient navigation. Cancer 2016;122:1060–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wohl AR, Dierst-Davies R, Victoroff A, et al. Implementation and Operational Research: The Navigation Program: An Intervention to Reengage Lost Patients at 7 HIV Clinics in Los Angeles County, 2012–2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;71:e44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shacham E, Lopez JD, Brown TM, Tippit K, Ritz A. Enhancing Adherence to Care in the HIV Care Continuum: The Barrier Elimination and Care Navigation (BEACON) Project Evaluation. AIDS Behav 2017;22:258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calhoun E, Esparza A. Patient Navigation: Overcoming Barriers to Care. 1st ed: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jean-Pierre P, Hendren S, Fiscella K, et al. Understanding the processes of patient navigation to reduce disparities in cancer care: perspectives of trained navigators from the field. J Cancer Educ 2011;26:111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ustjanauskas AE, Bredice M, Nuhaily S, Kath L, Wells KJ. Training in Patient Navigation: A Review of the Research Literature. Health promotion practice 2016;17:373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shelton RC, Thompson HS, Jandorf L, et al. Training experiences of lay and professional patient navigators for colorectal cancer screening. J Cancer Educ 2011;26:277–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. 2019. (Accessed September 1, 2019, at https://patientnavigatortraining.org.)

- 51.Level 2 Courses: Care Coordination for Patient Navigators. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. at https://patientnavigatortraining.org/courses/level2/.) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Level 1: Health Navigation Fundamentals. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. at https://patientnavigatortraining.org/courses/level1/.) [Google Scholar]

- 53.McKenney KM, Martinez NG, Yee LM. Patient navigation across the spectrum of women’s health care in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Introduction to Chronic Disease. Colorado Patient Navigator Training Program, 2011. at https://www.patientnavigatortraining.org/chronic_disease/index.htm.) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Introduction to the Healthcare System. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative. at https://patientnavigatortraining.org/elearning/courses/introduction-to-the-healthcare-system/.) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preventative Healthcare 101. Colorado Patient Navigator Training Program, 2011. at https://www.patientnavigatortraining.org/preventive_healthcare/index.htm.)

- 57.Motivational Interviewing: A Brief Overview. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative,. at https://patientnavigatortraining.org/elearning/courses/motivational-interviewing-a-brief-overview/.) [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Cancer Society,, 2020. at https://navigationroundtable.org/.)

- 59.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Motivational Interviewing: A Tool for Behavior Change. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:243–6.19104391 [Google Scholar]

- 60.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Benefits to Women of Medicaid Expansion Through the Affordable Care Act. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:223–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American College of Obstetricians And Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Breastfeeding in Underserved Women: Increasing Initiation and Continuation of Breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 63.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Healthcare for Homeless Women. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:936–40.24084568 [Google Scholar]

- 64.American College of O, Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved W. Committee opinion no. 591: challenges for overweight and obese women. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:726–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:250–5.25560140 [Google Scholar]

- 66.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist Committee on Obstetric Practice. Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:e32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bedsider. at https://www.bedsider.org/.)

- 68.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Health Literacy to Promote Quality of Care. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:e183–6.27661657 [Google Scholar]

- 69.American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e130–4.26595584 [Google Scholar]

- 70.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Health Care for Unauthorized Immigrants. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:755–9.25730255 [Google Scholar]

- 71.American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists Committee on Healthcare for Underserved Women. Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Awareness in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists. Health Disparities in Rural Women, Committee Opinion No 586. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:384–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laderman M, Renton M. Providing safe, high-quality maternity care in rural US Hospitals. Boston, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 74.FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Screening for Perinatal Depression. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:e208–e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, Sluyter D. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. Mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21 Suppl 1:S28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Project Implicit. 2020. August 1, 2020, at https://implicit.harvard.edu.)

- 78.Managing Difficult Patient Encounters,. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative, 2015. at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nqj_RAFDo0&feature=youtu.be.) [Google Scholar]

- 79.LGBTQ Cultural Responsiveness Webinar. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative, 2018. at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fCBYp2eYCdI&t=2776s.) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seminar on Poverty and Self-Sufficiency. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative, 2013. at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rORuu0UTrk4&feature=youtu.be.) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Service Standards for Patient Navigators. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative, 2013. at http://csph.ucdenver.edu/cphp/CO_Patient_Nav/Use_of_interpreters/index.htm.) [Google Scholar]

- 82.Basic Crisis Management Skills for Patient Navigators. Patient Navigator Training Collaborative, 2016. at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOSPrLQrtKA&feature=youtu.be.)

- 83.Successful Implementation of Clinical Preventative Service: Interventions to Promote Breastfeeding. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,, 2020. at https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars/interventions-to-promote-breastfeeding.) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maintaining Breastfeeding Beyond the First Week. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,, 2020. at https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars/breastfeeding-beyond-the-first-week.)

- 85.Implicit Bias. UC Regents, 2020. at https://equity.ucla.edu/know/implicit-bias/.)

- 86.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Louis JM, et al. Interpregnancy Care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220:B2–B18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 649: Racial and ethnic disparities in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 493: Importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]