Abstract

Background:

Oral monosaccharides and disaccharides are used to measure in vivo human gut permeability through urinary excretion.

Aims:

1. To obtain normative data on small intestinal and colonic permeability; 2. To assess variance on standard 16g fiber diet performed twice; 3. To determine whether dietary fiber influences gut permeability measurements; 4. To present pilot data using 2 selected probes in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D).

Methods:

Sixty healthy female and male adults, age 18–70y, participated in 3 randomized studies (2 studies on 16.25g and 1 on 32.5g fiber) in otherwise standardized diets. At each test, the following sugars were ingested: 12C-mannitol, 13C-mannitol, rhamnose (monosaccharides), sucralose and lactulose (disaccharides). Standardized meals were administered from 24h before and during 24h post-sugars with 3 urine collections: 0–2, 2–8, and 8–24h. Sugars were measured by HPLC-MS. Eighteen patients with IBS-D underwent 24h excretion studies after oral 13C-mannitol and lactulose.

Results:

Baseline sugars (>3-fold above lower limits of quantitation) were identified in the 3 studies: 12C-mannitol in all participants; sucralose in 4–8, rhamnose in 1–3. Median excretions/24h (% of administered dose) for 13C-mannitol, rhamnose, lactulose and sucralose were respectively ~30%, ~15%, 0.32% and 2.3%. 13C-mannitol and rhamnose reflected mainly small intestinal permeability. Intra-individual saccharide excretions were consistent, with minor differences with 16.25g vs. 32.5g fiber diets. Median COVinter was 76.5% (10–90%ile: 34.6–111.0). There were no significant effects of sex, age, or BMI on permeability measurements in health. 13C-mannitol measurements are feasible in IBS-D.

Conclusion:

Baseline 12C-mannitol excretion precludes its use; 13C-mannitol is the preferred probe for small intestinal permeability.

Keywords: barrier, lactulose, mannitol, sucralose

LAY SUMMARY

This paper describes optimization of methods to measure the barrier function of the intestine as it relates to possible “leaky gut” and its treatment. The test involves ingesting a sweet drink consisting of different sugars in water and collecting urine in three time periods over 24h.

Graphical Abstract

BACKGROUND

There are consistent claims suggesting that nutrients or supplements and possibly medications alter intestinal barrier function or cause the “leaky gut”. Nevertheless, these claims remain unsubstantiated.1–4 Regulatory agencies5,6 have provided guidance regarding structure and function and health claims. There is a need to develop a framework to objectively appraise the permeability of the gut barrier that may then be applied in the study of gut barrier function in a host of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal pathologies. Structure and function claims regarding nutrients and supplements require primary evidence from human studies demonstrating that a dietary component is causally associated with maintaining or restoring normal gut barrier structure (e.g., mucus layer thickness) or function of the human intestinal barrier (e.g., “normal” permeability or epithelial cell immune function) or a physiological benefit to normal gut barrier permeability and gut immunological function.3 In addition, health claims require human studies demonstrating a clinically and statistically significant relationship between the dietary component and accepted indicators of risk for, or progression to, specific intestinal or extra-intestinal health conditions.3 Maintaining normal gut permeability is considered to have a meaningful functional role in the digestive tract; dietary components (such as, but not limited to, fiber) may help maintain health in the general population. A first step in supporting function claims is, therefore, developing and validating measurements of the function of the human intestinal barrier. A standardized protocol combined with an established range of normal permeability will enable research that addresses currently unsubstantiated claims that diet and, possibly, medications lead to compromised intestinal barrier or “leaky gut.”

There are diverse methods used to assess intestinal and colonic permeability (see Supplemental Materials). The range of tests, molecular sizes of probe molecules (Supplemental Table 1), and prior reports in the literature are summarized elsewhere.3,4 Prior studies using concomitantly administered radioisotopes and oral sugars in humans have demonstrated that urine collections from 0–2 hours reflect small intestinal permeability and those from 8–24 hours reflect colonic permeability. In the collection between 2 and 8 hours after oral administration of the probes, it was demonstrated that the molecules were located in both the small intestine and colon, with significant inter-individual variation, such that it was not possible to attribute the 2–8 hour collection unequivocally to the small intestine or colon.7

There are no current data providing normal values and performance characteristics of the methods based on a reasonable size cohort of healthy participants of both genders. As a result, there is no conformity in the literature regarding the methods used to characterize intestinal barrier function. The selection of probe molecules includes diverse monosaccharides such as mannitol or rhamnose, several disaccharides such as cellobiose, lactulose, and sucralose, and other inert substances such as ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) or lower molecular weight polyethylene glycol (PEG) which is a polydisperse of molecules with average molecular weight 400. The molecular weight and estimated or documented molecular diameters of these probe molecules are included in Supplemental Table 1.

There are potential confounders or challenges in the assessment of intestinal permeability: first, differences between participants based on alcohol intake, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and strenuous exercise; second, differences in diet such as fiber and fat intake; third, differences related to age and sex. An additional confounder is that probe molecules may be constituents identified at baseline, typically from inadvertent intake in the diet or cosmetic products. For example, mannitol is found in high levels in several fruits and vegetables such as watermelon, clingstone peaches, button mushrooms, cauliflower, celery, snow peas, butternut squash and sweet potatoes. Mannitol is also used as a sweetener and is added to ‘sugar-free’ foods and beverages, protein powders, baked goods, and chewing gum, as well as to some liquid medications or skin care products to bind moisture and help keep ingredients blended together. Rhamnose is present in foods such as oranges, French beans, and winter cabbage, and has skin-soothing properties. Baseline presence in urine prior to administration as an oral probe has been demonstrated in prior studies that used mannitol or rhamnose.8,9 Although the prevalence of such confounders was unknown, it led to the development of 13C-mannitol, which lacks ubiquitous environmental presence, as an oral probe for measurement of intestinal and colonic permeability.8 Like mannitol, 13C-mannitol may be reliably measured in urine at specified time points to determine small intestinal and colonic permeability, but is distinguished from mannitol that is inadvertently consumed by subjects outside the study.

Our study hypotheses were that oral saccharide tests can be standardized to identify normal values of small intestinal and colonic permeability in healthy human adult participants, and that there are no differences in the measurements of intestinal permeability when adults are administered diets containing 16.25g or 32.5g fiber per day.

The aims of our study were to measure small intestinal and colonic permeability based on urine excretion of oral probe molecules in 60 healthy, white, female and male adults, aged 18–70 years, and specifically to obtain normative data (median, 10th and 90th percentile) as well as inter-individual coefficient of variation [COV, assessed by (SD/mean)], with approximately 15 participants in each of the following age groups: 18–30, 31–45, 46–60, and 61–70 years. A second aim was to assess intra-individual variance (assessed by median and IQR) in the measurements of permeability on two occasions in which participants received 16.25g fiber per day. A third aim was to determine whether fiber levels need to be standardized in a test for gut permeability by comparing measurements of permeability on standard diets containing 16.25g or 32.5g fiber per day. The latter objective was not intended to appraise the effect of fiber on barrier function (which would likely require longer term administration), but to assess whether variations in fiber intake within the typical recommended range of intake among adults in the U.S. result in altered estimated barrier function using the probe molecules. A fourth aim was to present pilot data using 2 selected sugar probes in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D).

METHODS

Ethical Approval

The healthy participant study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB #19–008541); the study of patients included in the pilot assessment of permeability in IBS-D was also approved (IRB #16–001445). All participants signed written informed consent.

Rationale, Design, Conduct of Study and Methods

Rationale

Since it is conceivable that the fiber content of the diet may impact the measured intestinal permeability, we carefully considered the amounts of fiber to be tested as we tried to develop a standardized method for measuring intestinal permeability. The NHANES What We Eat In America Survey10 reported that the “mean dietary fiber intake of all individuals 2 years and older, excluding breastfed children, was 16 grams per day.” Using the recommended amount of fiber of 14g/1000kcal, the average intake for women and men would be 25g/day and 38g/day respectively, or, on average, 32.5g/day for the two genders. The fiber level reportedly consumed by the majority of U.S. adults is ~50% of the recommended average for the two genders; therefore, half the recommended fiber intake of 16.25g/day (which corresponds with typical diets in the U.S.) was selected for the lower fiber intake, and the average recommended intake of 32.5g/day was selected for the higher level (Supplemental Tables 2A and 2B). The difference was also considered sufficient to understand the intra- and inter-individual coefficients of variation associated with differing fiber intakes.

Design

All healthy participants underwent 3 studies (cross-over design, in randomized order) each lasting 24 hours: on two occasions, the fiber intake during the 24 hours before and the 24 hours during the study was standardized with 16.25g fiber in the diet; on the third occasion, the fiber intake was 32.5g in 24 hours. The order of the diets was randomized so that the higher fiber (32.5g/day) standard diet was randomly assigned to a third of participants at the first, second, and third test.

In the patients with IBS-D, the same procedure was followed except that only 2 sugars were administered orally: 100mg of 13C-mannitol and 1000mg of lactulose. These studies were also conducted during a day when the meals were standardized: 320kcal egg meal for breakfast, 550kcal solid liquid meal for lunch, and 750kcal meal for dinner.

Randomization

A randomization block schedule was prepared by a statistician from the Mayo Clinic Biostatistics Department, with randomization balanced to the greatest extent possible for gender within the following age groups: 18–30 (n=15), 31–45 (n=15), 46–60 (n=15), and 61–70 (n=15) years.

Participants

Participants were healthy, non-obese, non-pregnant, white, 18–70 years of age, with male to female ratio of 1:1, and body mass index (BMI) ≤30kg/m2. The following were exclusion criteria: diabetes, hypertension, BMI ≥30kg/m2, and chronic NSAID use (>3 days/week). All healthy participants underwent interview and examination at baseline and this included a short form bowel disease questionnaire (derived from a validated long bowel disease questionnaire11) to exclude potential participants with relevant gastrointestinal symptoms or prior gastrointestinal diseases; patients also filled in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Inventory12.

Probe Molecules and Assays to Assess in vivo Intestinal and Colonic Permeability

These are addressed in the Supplemental Materials.13,14 Endpoints to evaluate intestinal permeability were urine excretion of probe molecules at 0–2h (reflecting small bowel permeability) with primary interest in 13C-mannitol, mannitol and rhamnose; and urine excretion of probe molecules at 8–24h (reflecting colonic permeability)5 with primary interest in lactulose and sucralose.

In each of the three studies conducted in each participant, we also obtained baseline fasting urine to assess the presence of any of these saccharide molecules which may be ingested from the diet or through the application of skin preparations. We detected a significant baseline constituent if there was a urine level that was >3-fold concentration compared to the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for each sugar. In addition, major contamination was noted when the concentration of any sugar molecule in baseline urine was >10μg/mL.

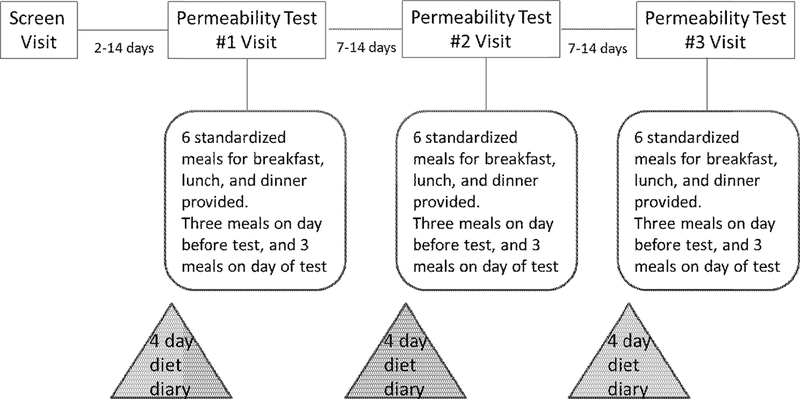

Experimental Protocol and Conduct of Studies

The overall study conduct is summarized in Figure 1. In preparation for the test days, no strenuous exercise (>5 miles running or equivalent exercise) during the prior week and no alcohol, soda or artificial sweeteners were allowed for 48 hours before participation. In view of well-established evidence of damage to barrier function with NSAIDs,15 their use was not permitted for two weeks prior to initial testing and during the three cross-over testing periods. Use of acetaminophen was permitted.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol

Self-reported food and drink diet records were collected for four days before each test day in case there were levels of addition of known sweeteners per se (e.g., sucralose) which would compromise the interpretation of the measurements of intestinal and colonic permeability; inclusion of any sugars as natural constituents of foods was not an exclusion criterion. The macronutrient, grams of fiber and calorie analyses were obtained based on food diaries, as well as the standardized diets administered in accordance with the randomization schedule for 48 hours during each of the three test periods.

Participants were provided with the following instructions to be followed during the 24-hour permeability studies in the Clinical Research Trials Unit: fast for at least 8 hours prior to ingestion of oral probe molecules; provide a baseline urine sample before ingestion of sugars (to assess for possible “contamination” with the probe molecules); no food ingestion for two hours after oral ingestion of the sugars; ingestion of sugars dissolved in 250mL water; 30 minutes after sugar ingestion, the participants were given a bottle of water (500mL) with instructions to ingest all water within 90 minutes, that is, before completion of the 0–2 hour urine collection; ingestion of standard breakfast two hours after the oral sugar solution; and no intake of alcohol soda or artificial sweeteners until completion of the 24-hour urine collection.

Participants were instructed to eat their prepared sack breakfast meal, and were each provided with three urine collection containers (0–2h, 2–8h and 8–24h), a prepared sack lunch to be ingested four hours after breakfast, and a prepared sack dinner to be consumed six hours after lunch.

The urine collections could occur in their workplace or at home, and the urine samples were kept cool or refrigerated.

A. Replicate studies

Using the randomization schedule provided by the study biostatistician, the entire program was repeated on two other occasions, separated by 7–14 days, to examine intra-individual variation while each participant received 16.25g fiber in each 24-hour diet and to examine the effect of varying the diet by standardizing intake of 16.25g or 32.5g fiber per day.

B. Standardized diets to determine whether fiber levels need to be standardized in a test for gut permeability

From 24 hours before the actual study, standardized diets were ingested. Participants started their three meals for the day (identical to those used in the test day) by picking up the meals (Supplemental Tables 2A and 2B) from the Clinical Research Trials Unit diet kitchen, and they ingested the meals at work or at home. There were 16.25g or 32.5g of fiber from foods (not from supplements) in the day’s diet, and the fat (30%), protein (20%), and carbohydrate (50%) macronutrient contents were standardized with calorie content based on BMI. Since no strenuous exercise (>5 miles running or equivalent exercise/week) was permitted, calorie intake was based on recommendations related to BMI, uncorrected for energy expenditure.

C. Pilot studies in patients with IBS-D

Similar studies were also performed in the separate cohort of 18 patients with established clinical diagnosis of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome16 who underwent studies of gut permeability (NIH R01-DK115950) in order to assess the applicability of the method in patients. Eight of these patients also had evidence of increased bile acid synthesis17,18 (fasting serum 7αC4 >52.5ng/mL) which is highly suggestive of bile acid diarrhea.19 These studies of intestinal permeability were performed during 24 hours during which gastrointestinal and colonic transit was measured, and three standard diets were ingested containing 320kcal at breakfast, 550kcal at lunch and 750kcal at dinner.

Endpoints

The primary endpoints for statistical analysis were 0–2h and 8–24h mass (mg) urinary excretion of each probe molecule reflecting small intestinal and colonic permeability, respectively, intra-individual variance on replicate studies, COVinter for each probe molecule with 16.25g fiber/day, and probe molecule excretion during 16.25g and 32.5g fiber/day.

The secondary endpoints were the disaccharide to monosaccharide excretion ratios based on the percentage of administered dose of each probe molecule in the 0–2h and 8–24h collections: lactulose:rhamnose ratio; lactulose:13C-mannitol ratio; sucralose:rhamnose ratio; and sucralose:13C-mannitol ratio. Other secondary endpoints were 8–24h mass (mg) urinary excretion of each probe molecule reflecting both small bowel and colonic mucosal permeability.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to develop normative data based on 60 healthy participants: median, and interquartile range (IQR). We also calculated inter-and intra-individual variations, with the latter being plotted using Bland-Altman plots. The day-to-day variability and effects of standardized 16.25g and 32.5g fiber/day diets were assessed using ANOVA. Additional statistical analyses compared the effect of sex, based on 30 males and 30 females; effect of age, based on three groups that had approximately equal numbers recruited (<31, 31–53, and >53 years of age); and effect of BMI 18–24.99 kg/m2 or 25–29.99 kg/m2. Given the presentation of pilot data from the patients with IBS-D, the data for the two sets of patients with normal or elevated fasting serum 7αC4 are described and summarized in a figure, and no formal statistical analysis was performed.

Values of P<0.05 were used for nominal significance and values of P<0.10 were also recorded. Statistical power is addressed in Supplemental Materials.

RESULTS

Healthy Participant Demographics

There were 30 male and 30 female healthy participants who were matched for each 10 years of age. The average age was 45.2±15.6 (SD) years; their mean height was 170.8±8.4cm; weight was 75.05±12.36kg; and BMI was 25.14±2.69 kg/m2.

Baseline Urine Sugars in Healthy Participants

Baseline identification >3* LLOQ of sugars (Supplemental Table 4) was observed with mannitol for all 60 participants, with urine concentrations >10μg/mL in 66% of participants Other sugars were identified during the three separate studies in baseline urine at concentrations >3* LLOQ as follows: 4 to 8 participants for sucralose, 1 to 3 for rhamnose, 1 (minimally above 3* LLOQ) for lactulose, and none for 13C-mannitol.

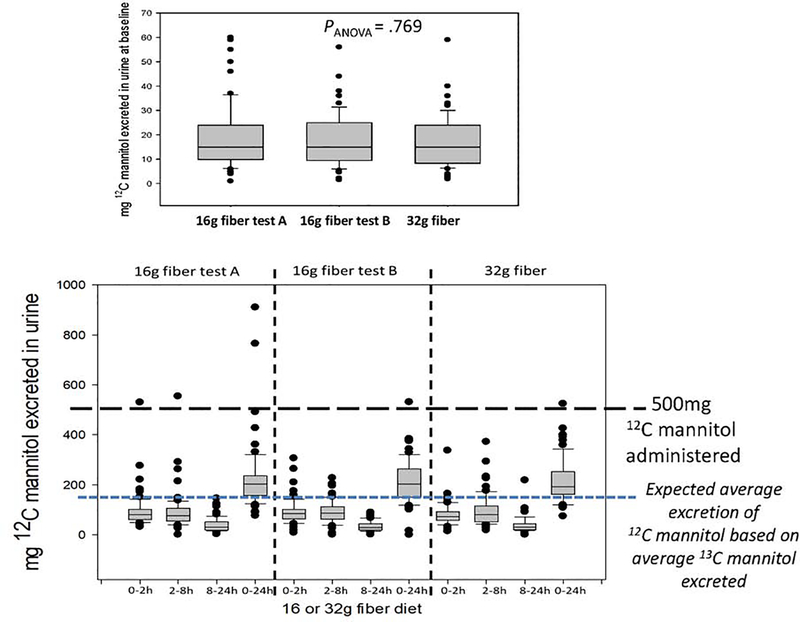

12C-Mannitol Excretion at Baseline and Following Ingestion of Sugars in Healthy Participants

Figure 2 shows the baseline urine 12C-mannitol in the three different study days (upper panel) and the mass (mg) of 12C-mannitol recovered after oral administration of 500mg 12C-mannitol in the three urine collections during each 24-hour study period. It is noteworthy that, despite the administration of 500mg of 12C-mannitol, the cumulative urine excretion actually exceeded 500mg in a few participants, confirming that, even during the standardized diets, some exogenous mannitol must have been a constituent of the mass excreted, especially given the fact that, on average, the mass of 13C-mannitol excreted over the entire 24 hours was 30mg (that is ~30%) and, therefore, the average 12C-mannitol excretion over 24 hours would be around 150mg. Based on Figure 2, the lower margin of the IQR is about 150mg, suggesting that 75% of the healthy adult participants had more 12C-mannitol in the urine than the average that would be anticipated to be excreted over 24 hours.

Figure 2.

12C-mannitol in urine samples collected at baseline (upper panel) and during urine collections over 24 hours during three test days

Urinary Excretion of Oral Saccharides in Healthy Participants

Supplemental Figure 1 shows the full data, including 5–95%iles for each saccharide excretion in each urine collection and in the 24-hour periods. The median and IQRs are also tabulated in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Median (interquartile range, IQR) mg during 2 study days (fiber 16.25g/day Study A and B); note the small within individual difference suggesting concordance and reproducibility of results for all sugars with each urine collection

| Sugar (dose used) | Time | Median (IQR) mg on 16.25g fiber /day (A) | Median (IQR) mg on 16.25g fiber /day (B) | Within individual difference in mg excreted in study A and B on 16.25g/day fiber |

P value 16.25g fiber/day A vs B | COVinter % study A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

13 C mannitol 100mg |

0–2 h | 15.0 (11.5, 20.0) | 17.0 (12.0, 20.0) | 0 (−3.3, 4.0) | NS | 90.7 |

| 2–8 h | 12.0 (8.4, 16.0) | 15.0 (11.0, 19.0) | −2 (−5, 4.5) | NS | 103.5 | |

| 8–24 h | 1.7 (1.1, 2.85) | 1.7 (0.90, 2.70) | 0.2 (−0.5, 0.9) | 0.09 | 111.0 | |

| 0–24 h | 30.1 (25.2, 36.95) | 31.9 (24.7, 42.3) | −1.1 (−8.9, 7.9) | NS | 75.8 | |

| Rhamnose 200mg | 0–2 h | 10.9 (8.53, 15.05) | 11.7 (8.49, 15.4) | −0.03 (−3.7, 2.2) | NS | 124.1 |

| 2–8 h | 10.35 (7.92, 14.6) | 11.9 (7.67, 16.0) | −0.75 (−5.1, 3.2) | NS | 116.2 | |

| 8–24 h | 2.785 (1.76, 4.81) | 2.67 (1.74, 4.25) | 0.44 (−0.52, 1.35) | 0.09 | 76.5 | |

| 0–24 h | 25.95 (20.2, 31.82) | 27.5 (20.65, 34.26) | −1.29 (−6.27, 6.54) | NS | 89.5 | |

| Lactulose 1000mg | 0–2 h | 1.25 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 0.1 (−0.3, 0.4) | NS | 97.1 |

| 2–8 h | 1.42 (1.15, 2.3) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.8) | 0 (−0.7, 0.6) | NS | 87.6 | |

| 8–24 h | 0.29 (0.29, 0.295) | 0.29 (0.29, 0.29) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.09 | 91.7 | |

| 0–24 h | 3.195 (2.34, 5.29) | 3.29 (2.39, 4.89) | 0 (−0.60, 1.11) | NS | 71.4 | |

| Sucralose 1000mg | 0–2 h | 7.12 (5.44, 9.86) | 7.25 (4.42, 9.75) | 0.36 (−1.04, 3.42) | 0.13 | 99.4 |

| 2–8 h | 9.64 (7.21, 12.5) | 10.20 (7.46, 14.50) | 0.3 (−3.80, 2.98) | NS | 81.0 | |

| 8–24 h | 4.27 (3.44, 8.15) | 4.1 (3.00, 7.07) | 0.60 (−0.65, 2.24) | 0.04 | 55.8 | |

| 0–24 h | 23.59 (17.41, 30.02) | 21.98 (17.80, 28.15) | 0.93 (−3.40, 6.53) | 0.13 | 63.5 | |

| %L/RR | 0–2 h | 0.022 (0.017,0.027) | 0.019 (0.016, 0.025) | 0.00 (−0.003, 0.007) | NS | 50.0 |

| %L/RR | 8–24 h | 0.05 (0.016,0.038) | 0.023 (0.016,0.040) | −0.004(−0.01, 0.009) | NS | 49.1 |

| %L/13CMR | 0–2 h | 0.008 (0.006,0.011) | 0.007 (0.006,0.010) | 0 (−0.0004, 0.0026) | 0.03 | 52.3 |

| %L/13CMR | 8–24 h | 0.019 (0.013,0.033) | 0.019 (0.012,0.034) | −0.0015 (−0.007, 0.003) | NS | 80.7 |

| %S/RR | 0–2 h | 0.124 (0.108,0.146) | 0.116 (0.098, 0.145) | 0.005 (−0.016, 0.033) | NS | 25.6 |

| %S/RR | 8–24 h | 0.318 (0.253,0.448) | 0.307 (0.222, 0.451) | −0.0003 (−0.089, 0.069) | NS | 54.0 |

| %S/13CMR | 0–2 h | 0.049 (0.042,0.058) | 0.045 (0.041, 0.056) | 0.0026 (−0.004, 0.01) | 0.04 | 32.1 |

| %S/13CMR | 8–24 h | 0.276 (0.187,0.376) | 0.269 (0.187, 0.354) | 0.0018 (−0.062, 0.073) | NS | 68.1 |

L=lactulose; 13CM = 13Cmannitol; R=rhamnose; S=sucralose; L/RR = lactulose to rhamnose ratio; L/13CMR= lactulose to 13Cmannitol ratio; S/RR = sucralose to rhamnose ratio; S/13CMR= sucralose to 13Cmannitol ratio

Table 2.

Median (interquartile range, IQR) mg fiber 16.25g/day during studies A and B vs. fiber 32.5g/day during the third study; note sequence of studies was randomized (double-blind)

| Saccharide (dose used) | Timed urine collection | Median (IQR) mg or ratio avg. of 2 studies with 16.25g fiber/day | Median (IQR) mg or ratio with 32.5g fiber /day | Variance mg for avg. of 2 studies with 16.25g vs. 32.5g fiber /day | P avg. 16.25g vs. 32.5g/day fiber |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 C-mannitol 100mg | 0–2 h | 15.25 (12.0, 20.5) | 13.0 (10.0,18.0) | 1.375 (−1.5, 6.25) | 0.04 |

| 2–8 h | 13.22 (9.62, 17.25) | 15.0 (8.7, 20.5) | −0.525 (−5.1, 2.275) | 0.09 | |

| 8–24 h | 1.8 (1.15, 2.82) | 2.35 (1.5, 3.6) | −0.20 (−1.2, 0.4) | 0.06 | |

| 0–24 h | 32.05 (25.55, 37.57) | 31.25 (25.75, 39.9) | −1.075 (−8.59, 7.35) | NS | |

| Rhamnose 200mg | 0–2 h | 11.48 (9.40, 14.85) | 10.55 (7.54, 14.05) | 1.46 (−1.86, 3.88) | 0.07 |

| 2–8 h | 10.85 (8.06, 15.15) | 12.55 (7.275, 16.9) | −0.60 (−3.40, 2.27) | NS | |

| 8–24 h | 3.12 (1.75, 4.56) | 2.19 (1.50, 3.64) | 0.58 (−0.595, 2.35) | 0.06 | |

| 0–24 h | 26.04 (21.43, 33.15) | 26.14 (20.05, 34.33) | 0.522 (−6.96, 7.35) | NS | |

| Lactulose 1000mg | 0–2 h | 1.2 (0.9, 1.95) | 1.10 (0.7, 1.65) | 0.13 (−0.025, 0.55) | 0.006 |

| 2–8 h | 1.575 (1.17, 2.40) | 1.75 (1.3, 2.8) | −0.275 (−0.825, 0.175) | 0.01 | |

| 8–24 h | 0.29 (0.29, 0.30) | 0.29 (0.29, 1.0) | 0.00 (−0.51, 0.00) | <0.001 | |

| 0–24 h | 3.42 (2.49, 4.69) | 4.04 (3.09, 5.345) | −0.40 (−1.48, 0.45) | 0.03 | |

| Sucralose 1000mg | 0–2 h | 6.895 (4.91, 10.38) | 6.655 (4.59, 9.765) | 0.427 (−0.757, 2.626) | 0.05 |

| 2–8 h | 9.92 (7.52, 12.77) | 10.85 (8.25, 15.15) | −0.155 (−2.52, 1.59) | NS | |

| 8–24 h | 4.75 (3.28, 6.72) | 5.445 (3.69, 7.88) | −0.262 (−2.35, 0.925) | 0.07 | |

| 0–24 h | 22.26 (17.96, 29.98) | 24.31 (20.17, 30.51) | −1.482 (−6.40, 3.67) | NS | |

| %L/RR | 0–2 h | 0.021 (0.016,0.028) | 0.021 (0.016, 0.028) | 0.0006 (−0.0049, 0.0053) | NS |

| %L/RR | 8–24 h | 0.027 (0.018,0.035) | 0.044 (0.031,0.064) | −0.014 (−0.033, -0.001) | <0.001 |

| %L/13CMR | 0–2 h | 0.008 (0.006,0.010) | 0.008 (0.006,0.011) | 0.0003 (−0.001, 0.002) | NS |

| %L/13CMR | 8–24 h | 0.02 (0.015,0.033) | 0.023 (0.014,0.034) | 0.0004 (−0.009, 0.007) | NS |

| %S/RR | 0–2 h | 0.122 (0.103, 0.147) | 0.123 (0.101, 0.142) | −0.0009 (−0.018, 0.024) | NS |

| %S/RR | 8–24 h | 0.352 (0.245,0.445) | 0.404 (0.318, 0.619) | −0.101 (−0.242, 0.038) | <0.001 |

| %S/13CMR | 0–2 h | 0.047 (0.040,0.056) | 0.047 (0.037, 0.052) | 0.001 (−0.004, 0.006) | NS |

| %S/13CMR | 8–24 h | 0.295 (0.199, 0.388) | 0.212 (0.144, 0.342) | 0.029 (−0.058, 0.109) | 0.09 |

L=lactulose; 13CM = 13Cmannitol; R=rhamnose; S=sucralose; L/RR = lactulose to rhamnose ratio; L/13CMR= lactulose to 13Cmannitol ratio; S/RR = sucralose to rhamnose ratio; S/13CMR= sucralose to 13Cmannitol ratio Variance expressed as result from average 16.25g fiber diet MINUS result with 32.5g fiber diet

Excretion Profiles in Healthy Participants

Median percent excretions of the sugar molecules were: 13C-mannitol 30%, rhamnose 12.5%, lactulose 0.3%, and sucralose 2.3% (Tables 1 and 2, and Figures 3 and 4). Based on the mass of saccharide absorbed from 0–8 hours, there was an average of at least 70% of 13C-mannitol, rhamnose, and sucralose, and at least 95% of the lactulose delivered to the colon.

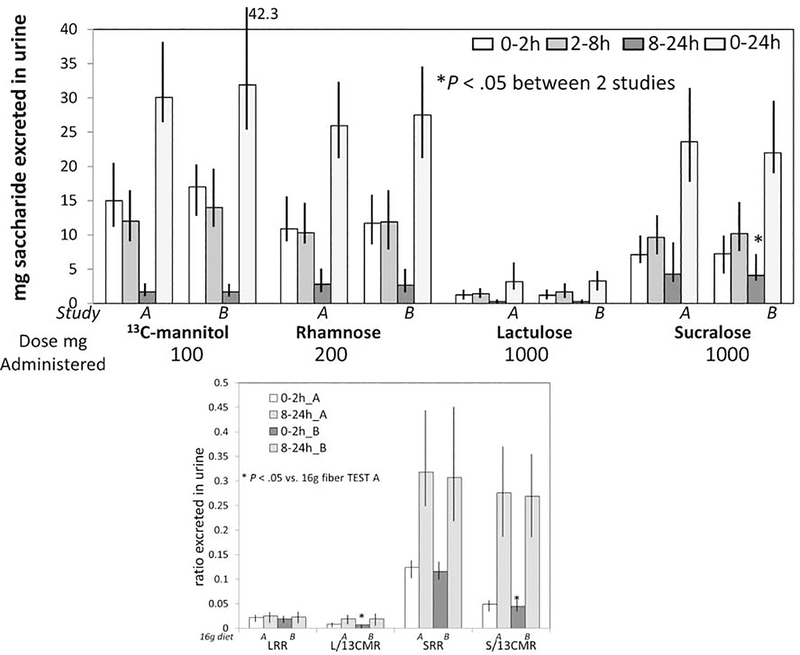

Figure 3.

Reproducibility of small intestinal (0–2h) and colonic (8–24h) permeability measurements based on mass (mg) of saccharide excreted in urine (upper panel) or ratio of disaccharide to monosaccharide (lower panel) during 2 studies (A and B) with standardized diets containing 16.25g fiber per day. Data show median and interquartile range, IQR. LRR=lactulose to rhamnose ratio, L/13CMR=lactulose to 13C-mannitol ratio, SRR=sucralose to rhamnose ratio, S/13CMR=sucralose to 13C-mannitol ratio

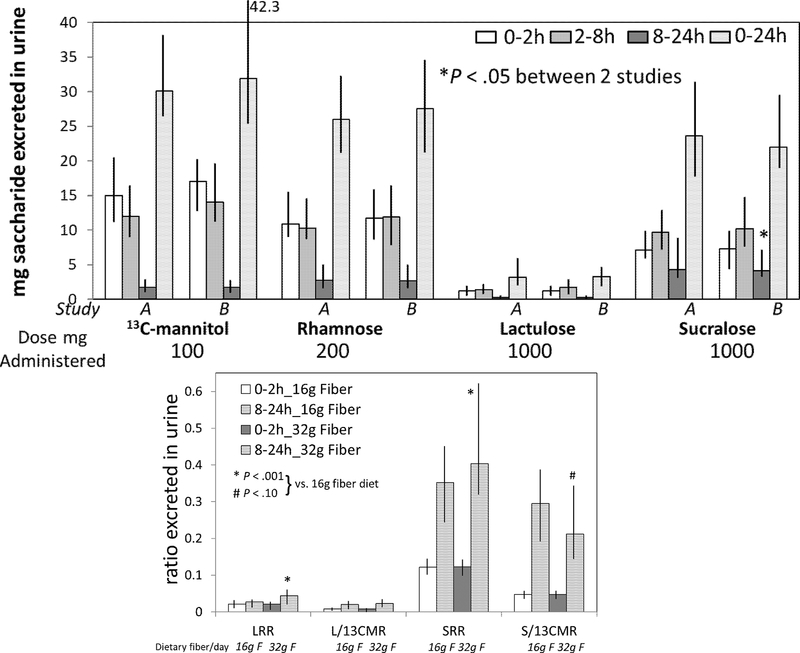

Figure 4.

Comparison of small intestinal and colonic permeability measurements based on mass (mg) of saccharide excreted in urine (upper panel) or ratio of disaccharide to monosaccharide (lower panel) during two studies (A and B) with standardized diets containing 16.25g fiber per day (mean of 2 studies) and 32.5g fiber per day. Data show median and interquartile range, IQR. LRR=lactulose to rhamnose ratio, L/13CMR=lactulose to 13C-mannitol ratio, SRR=sucralose to rhamnose ratio, S/13CMR=sucralose to 13C-mannitol ratio

13C-mannitol and rhamnose had similar excretion profiles, being absorbed predominantly in the small intestine, and with <2% median excretion reflecting colonic permeability. Sucralose was absorbed almost equally in both small intestine and colon. Lactulose absorption occurred predominantly in the small intestine, although some was also absorbed in the colon; however, all studies showed that <1% of the administered lactulose was actually absorbed or excreted over 24 hours. The vast majority of participants excreted no lactulose in the urine above the lower limit of quantitation between 8 and 24 hours on either of the two study days (49 in study A and 52 in study B) associated with16.25g fiber/day in the diet. On the other hand, 23 participants passed more than the lower limit of quantitation of lactulose during the 32.5g fiber/day diet study.

Intra-individual saccharide absorption/excretion profiles with 16.25g fiber/day were consistent for the four individual sugars, but there were minor differences between the two studies, reaching nominal statistical significance for sucralose in the 8–24h collection (Table 1, Figure 3). These were also documented in the disaccharide to monosaccharide ratios, in addition to the absolute mass of sugars excreted.

The COVinter [SD/mean (%)] across all sugar measurements (mg excreted) during the first study conducted with 16.25g fiber diet was 75.3% (SD 26.6; and median 76.5%, 10–90%ile: 34.6–111.0). The COVinter for disaccharide to monosaccharide ratios was slightly lower (mean 51.5%; SD 17.7; 10th-90%ile 27.6–76.9).

Associations of Age, Sex, and BMI with Saccharide Excretion Profiles in Healthy Participants

There were 19 participants less than 31 years old, 21 participants between 31 and 53 years old, and 20 participants who were more than 53.1 years old; with a total of 30 males and 30 females. There were no significant effects of age (P=0.693) as a continuous variable or of sex (P=0.348) on measurements of permeability (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3).

Supplemental Figure 4 shows the comparison of 13C-mannitol excretion based on BMI cut-off of 25kg/m2. The subgroups’ BMI measurements were 22.3kg/m2 (IQR 21.5– 23.5) and 27.0kg/m2 (26.2–28.3), and the corresponding ages and sexes of the two groups were 39 (29–57) years with 10/27 males and 48 (33–61) years with 20/33 males. The excretion profiles showed minor numerical differences in the two groups dichotomized at BMI 25kg/m2 (Supplemental Figure 4).

Reproducibility of Permeability Measurements in Healthy Participants

Supplemental Figures 5 through 8 show Bland Altman plots for the 0–2h and 8–24h excretions of 13C-mannitol, rhamnose and sucralose during the two studies with diets containing 16.25g fiber; for lactulose the plots provided are for 0–2h excretion and 2–8h excretion, since 11 and 8 participants passed no lactulose in the urine during the two studies at 8–24h. Supplemental Figure 9 shows Bland-Altman plots for the 0–2 and 8–24h excretion of 13C-mannitol during 16.25g and 32.5g fiber diet studies. Note the marked reproducibility of all probe molecules, with variance usually well within 1 standard deviation and mean difference close to zero.

Comparison of Sugar Excretion Profiles on 16.25g and 32.5g Fiber Diets in Healthy Participants

Compared to excretion profiles during dietary fiber intake of 16.25g/day, the excretion profiles associated with fiber intake of 32.5g/day documented small, but significant differences in permeability measurements with three saccharides, and marginal differences for rhamnose (Figure 4 and Table 2). Excretions were lower when the participants ingested the 32.5g fiber diet for all four saccharide probes in the 0–2h urine collections (corresponding to small intestinal permeability), and excretion was higher for lactulose in the 8–24h urine collection in the 32.5g fiber study (colonic permeability). Lactulose to rhamnose ratio and sucralose to rhamnose ratio over the entire 24-hour period were significantly higher with the 32.5g fiber diet compared to the 16.25g fiber diet. However, the lactulose or sucralose to 13C-mannitol ratios were not significantly different between the two dietary fiber levels.

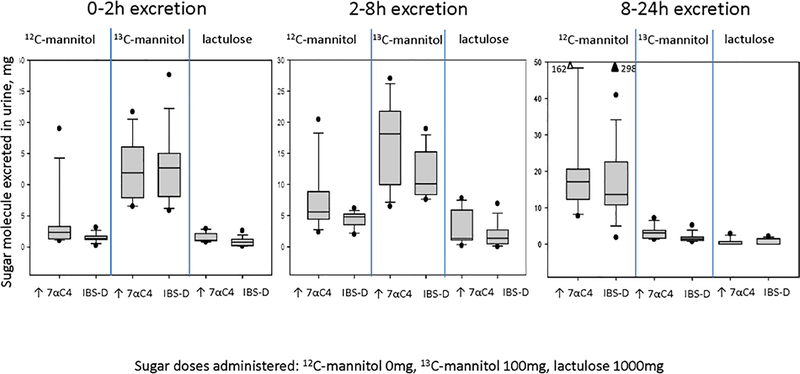

Pilot Studies in Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant IBS

There were 18 patients with IBS-D: 15 females and 3 males, with mean age 40.3±14.8 (SD) years, and mean BMI 30.7±6.8 (SD) kg/m2. Eight of the 18 patients had evidence of increased bile acid synthesis demonstrated by fasting serum 7αC4 >52.5ng/mL. Supplemental Table 5 provides further information on demographics in the two groups of patients with IBS-D based on normal or elevated fasting serum 7αC4. Figure 5 shows the data for the two sugars administered to these patients, that is, 13C-mannitol (100mg), and lactulose (1000mg). In addition, Figure 5 shows the quantitation of 12C-mannitol in urine between 0 and 24 hours. It is particularly noteworthy that there were significant quantities of 12C-mannitol in each of the three urine collections, particularly in the 8–24 hour urine collection, consistent with inadvertent contamination with 12C-mannitol. In addition, there were no significant group differences (high serum 7αC4 vs. normal serum 7αC4) in the excretion of 13C-mannitol and lactulose in all 3 urine collections.

Figure 5.

Urine excretion of 12C-mannitol, 13C-mannitol, and lactulose in urine between 0 and 24 hours following administration of 100mg 13C-mannitol and 1000mg lactulose in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Note the significant quantities of 12C-mannitol particularly in the 8–24h urine sample consistent with contamination and the comparable excretion of 13C-mannitol and lactulose in all 3 urine samples.

The median (IQR) 13C-mannitol excreted over 24 hours was 27.3mg (IQR, 16.8–40.8) in the high serum 7αC4 IBS-D group and 24.9mg (18.3–30.7) in the normal serum 7αC4 IBS-D group. These data are comparable to the 32.05mg (25.55–37.57, Table 2) measured on average in the healthy participants receiving 16.25g fiber diets on 2 occasions. Similarly, the median (IQR) lactulose excreted over 24 hours was 3.9mg (2.1–7.7) in the high serum 7αC4 IBS-D group and 2.4mg (1.7–3.9) in the normal serum 7αC4 IBS-D group. These data are comparable to the 3.42mg (2.49–4.69, Table 2) measured on average in the healthy participants receiving 16.25g fiber diets on two occasions.

DISCUSSION

Our studies inform best practices for in vivo measurements of small intestinal and colonic permeability using oral sugars, and provide a base from which to develop protocols for assessment of claims of improved barrier functions in accordance with regulatory guidance5,6. With further validation, this testing platform has potential to become a clinical diagnostic test with ingestion of non-radiolabeled probe sugars in a glass of water, collection of urine samples, and measurements performed by a centralized laboratory.

Methodological Insights

We have confirmed extensive environmental exposure and ingestion of mannitol8 which was observed in healthy participants and patients with IBS-D; 12C-mannitol as a constituent in baseline urine, and its pervasive presence in so many foods and other dietary and cosmetic substances precludes its use as a permeability probe. In patients with IBS-D, mannitol appeared in the three urine samples even though it was not one of the oral probes administered, and it must have been inadvertently ingested with standard meals.

There was <0.5% average absorption of lactulose over 24 hours, and only about 4–8mg (IQR) or 0.5 to 1% of the sucralose mass absorbed as a measure of colonic mucosal permeability, even though sucralose is not degraded by colonic bacteria. 20 This resistance to colonic degradation by bacteria contrasts with hexose and pentose sugars which are fermented by human colonic bacteria including Bacteroides, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria21 and lactulose which undergoes metabolism by colonic bacteria such as Clostridia and Lactobacilli.22 The low quantity absorbed by the colon raises questions as to their sensitivity and utility as colonic permeability markers in the non-inflamed or non-ulcerated gut. This limitation occurs despite the fact that, based on the mass of saccharide absorbed from 0–8 hours, there was an average of at least 70% of 13C-mannitol, rhamnose, and sucralose, and at least 95% of lactulose delivered to the colon. A corollary is that, with <1% disaccharide mass absorbed, observations of barrier function based on lactulose to monosaccharide ratios need to be reassessed, especially the lactulose to mannitol ratios, given the potential of inadvertent additional ingestion of mannitol in the diet further impacting the calculated ratio. If lactulose is to be used as a permeability marker, it may indeed be best to assess the excreted mass of that sugar rather than the lactulose to monosaccharide excretion ratio.

Our studies suggest that 13C-mannitol is the preferred probe for small intestinal permeability with highest excretion during 0–2 hours, followed by 2–8 hours, both of which reflect absorption through small bowel, given the propensity for bacterial degradation when 13C-mannitol reaches the colon. 13C-mannitol provides sensitivity to assess the paracellular pathway for small molecules in the small intestine, and therefore smaller molecular probes [e.g., creatinine, erythritol with estimated molecular diameters on 1 to 2Å smaller (Supplemental Table 1)] may not be necessary to assess small bowel permeability. Sucralose is absorbed both in the small intestine and in the colon23, and the proportion absorbed in the colon as well as lack of colonic bacterial fermentation make it an attractive probe molecule. However, the presence of sucralose in the diet (increasingly used in foods and beverages) may preclude its use as a permeability probe, or it may require education of participants to avoid intake of sucralose for at least 48 hours prior to commencement of the test and through completion of the 24h urine collection.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Our study has several strengths, including documentation of the reproducibility of urine excretion of sugar probe molecules during replicate studies containing the same balanced diet, calorie intake and fiber intake (Tables 1 and 2). Our results suggest that it is possible to devise experimental conditions that accurately measure small intestinal and colonic permeability. These conditions include preparation prior to the test performance, avoidance of substances such as alcohol, NSAIDs, and contaminating sugars, as well as avoidance of strenuous exercise24–26, all of which could either alter permeability or introduce confounders in the test interpretation. Such precautions are common for other clinical tests, but they emphasize the need for tight control of the protocol used for the test to have reliable results. We observed very small differences in the results obtained on diets containing 16.25g or 32.5g fiber per day, suggesting that such standardization of fiber content in diet may not be necessary. We also noted that results for 13C-mannitol and lactulose were generally similar in healthy participants on one type of diet and in patients with IBS-D on a different diet. Nevertheless, until further validation studies are done, it is probably advisable to standardize meals during the period of urine collection.

Our current study also provides normal values and inter-individual coefficients of variation, and demonstrates no significant effects of sex or age between 18 and 70 years, and minor numerical differences in healthy participants with BMI above or below 25 kg/m2, as illustrated in Supplemental Figures 2–4. Prior measurements performed on ileal biopsies from patients aged 7 to 77 years who were undergoing screening endoscopy for inflammatory or malignant diseases27 showed reduced transepithelial electrical resistance (suggesting increased permeability) in biopsies form older participants; however, mRNA expression of tight junction proteins did not vary with age, and overall permeability to macromolecules was not affected by age.

Another strength of our study was the inclusion of overweight participants (overall mean BMI 25.14kg/m2), since there is the need to develop normative data of relevance to adults in the United States with the average BMIs of U.S. adult men and women being 30.2 and 30.6kg/m2 respectively.

A weakness is the absence of data in obesity. The association of obesity (BMI >30.6kg/m2) with increased permeability is predominantly in association with complications such as diabetes, hepatic steatosis and systemic inflammation,28 and the permeability measurements in humans were based on methods with questionable accuracy or markers of mucosal damage [e.g., serum zonulin (18kDa) or lipopolysaccharide (50–100kDa)] rather than selectively studying increased permeability in the absence of mucosal damage, which is the main objective of our study.

Other weaknesses are the total number of participants was 60, and the lack of ethnic or racial diversity and pediatric age participants in the current cohort; future studies will be required to establish normal values across diverse groups.

Summary and Conclusion

In the absence of established criteria to measure intestinal permeability and in the absence of an established gold standard, we propose that the standard method to measure intestinal permeability in vivo in humans should be based on the balance between factors summarized in Supplemental Table 6. With further validation studies, it is conceivable that this test platform could be developed as a clinical diagnostic test based on 13C mannitol (0–2h collection reflecting small intestinal permeability) and the disaccharides lactulose or sucralose (2–8h collection reflecting permeability of both the small intestine and the colon) to measure permeability in vivo.. The method can also serve as a method to interrogate the potential “function claims” of dietary components and the intestinal barrier.

13C mannitol, as lactulose have low likelihood of being present in urine at baseline, and use of the sensitive, validated HPLC-MS assay allows the administration of low doses of the oral probes, which is particularly relevant for lactulose which at a dose of 1g that does not alter gastrointestinal secretion as a result of the small osmotic load. In addition, whereas the percentage of lactulose excretion in healthy individuals is limited even over 24 hours, we have previously shown that twice as much lactulose is excreted in patients with microscopic colitis or ulcerative colitis in remission, reflecting increased colonic permeability,7 thus illustrating its potential utility in diseases associated with minor alterations in colonic permeability. These advantages counterbalance the relative cost of 13C-mannitol ($65 for 100mg per participant used in the current study).

We conclude that the optimal probes for measurement of small intestinal and colonic permeability in vivo are respectively the mass excreted of 13C-mannitol at 0–2 hours and lactulose during 2–8 hours or sucralose (which is not metabolized by colonic bacteria) during 8–24 hours. Although the COVinter for the disaccharide to monosaccharide ratios are slightly lower than for individual sugar molecules, the low level of excretion of disaccharide mass during passage though the colon estimated at <1% argues against the use of the disaccharides alone or the ratio of disaccharide to monosaccharide as markers of mucosal permeability in non-inflamed or non-ulcerated intestine.

Supplementary Material

EDITORS NOTES.

Background and Context

There are consistent claims suggesting that nutrients or supplements and possibly medications alter intestinal barrier function, leading to a “leaky gut”. Urinary excretion of orally-administered sugar molecules is used to measure intestinal and colonic permeability.

New Findings

Mannitol, and to a lesser extent, rhamnose and sucralose appeared to be constituents in urine, even before oral administration in a test to evaluate intestinal or colonic permeability. This study validates the performance characteristics of the sugar probes, reproducibility, normal values (including effects of age, sex and BMI up to 30kg/m2) and optimization of test protocol to obtain reliable measurements of permeability.

Limitation

The study was conducted in 30 male and 30 female white adults, and studies in other racial and ethnic groups are required.

Impact

The availability of a robust, standardized, reproducible method to measure intestinal and colonic permeability will enhance studies of intestinal barrier function in health and disease and provide an objective measure for claims to regulatory authorities of altered function related to diverse nutrients and supplements.

Support:

Dr. Camilleri receives funding for studies on intestinal permeability in irritable bowel syndrome (unrelated to current project) from NIH (R01 DK115950).

The study was conducted in the Mayo Clinic Clinical Research Trials Unit, supported in part by nursing, dietetic, physiology and immunochemistry lab components, which are supported by grant number UL1-TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Funding for this study:

This work was supported by ILSI North America. ILSI North America is a public, nonprofit science foundation that provides a forum to advance understanding of scientific issues related to the nutritional quality and safety of the food supply. ILSI North America receives support primarily from its industry membership. ILSI North America had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of the data and results.

Abbreviations:

- 12Carbon

12C

- 13Carbon

13C

- BMI

body mass index

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid

- HPLC-MS

high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- IQR

interquartile range

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantitation

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Camilleri and Singh have submitted a patent application on “Methods and materials for assessing intestinal permeability; Publication number: 20190145953”

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Odenwald MA, Turner JR. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley EM. Leaky gut - concept or clinical entity? Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2016;32:74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilleri M, Lyle BJ, Madsen KL, et al. Role for diet in normal gut barrier function: developing guidance within the framework of food labeling regulations. Am J Physiol 2019;317:G17–G39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilleri M Invited Recent Advances in Basic Science: The leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut 2019;68:1516–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Evidence- Based Review System for Scientific Evaluation of Health Claims (Online). https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidancedocuments/guidance-industry-evidence-based-review-system-scientificevaluation-health-claims. [9 December 2018].

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Substantiation for Dietary Supplement Claims Made Under Section 403(r) (6) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Online). https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidancedocuments/guidanceindustry-substantiation-dietary-supplement-claims-made-under-section-403r-6-federal-food. [9 December 2018].

- 7.Rao AS, Camilleri M, Eckert DJ, et al. Urine sugars for in vivo gut permeability: validation and comparisons in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea and controls. Am J Physiol 2011;301:G919–G928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grover M, Camilleri M, Hines J, et al. 13C-mannitol as a novel biomarker for measurement of intestinal permeability. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;28:1114–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faubion WA, Camilleri M, Murray JA, et al. Improving the detection of environmental enteric dysfunction: a lactulose, rhamnose assay of intestinal permeability in children aged under 5 years exposed to poor sanitation and hygiene. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dwyer J, Picciano MF, Raiten DJ. Estimation of usual intakes: What we eat in America-NHANES. J Nutr 2003;133:609S–623S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc 1990;65:1456–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camilleri M, Nadeau A, Lamsam J, et al. Understanding measurements of intestinal permeability in healthy humans with urine lactulose and mannitol excretion. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:e15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lostia AM, Lionetto L, Principessa L, et al. A liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry method for the evaluation of intestinal permeability. Clin Biochem 2008;41:887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjarnason I, Scarpignato C, Holmgren E, et al. Mechanisms of damage to the gastrointestinal tract from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology 2018;154:500–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camilleri M, Nadeau A, Tremaine WJ, Lamsam J, Burton D, Odunsi S, Sweetser S, Singh R. Measurement of serum 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (or 7αC4), a surrogate test for bile acid malabsorption in health, ileal disease and irritable bowel syndrome using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009;21:734–e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donato LJ, Lueke A, Kenyon SM, Meeusen JW, Camilleri M. Description of analytical method and clinical utility of measuring serum 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (7aC4) by mass spectrometry. Clin Biochem 2018;52:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Acosta A, Shin A, Carlson P, Burton D, Ryks M, Rhoten D, Lamsam J, Lueke A, Donato LJ, Zinsmeister AR. Effect of increased bile acid synthesis or fecal excretion in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1621–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meddings J, Gibbons I. Discrimination of site- specific alterations in gastrointestinal permeability in the rat. Gastroenterology 1998;114:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, et al. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;9:577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahota SS, Bramley PM, Menzies IS. The fermentation of lactulose by colonic bacteria. J Gen Microbiol 1982;128:319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McOmber ME, Ou C-N, Shulman RJ. Effects of timing, sex, and age on site-specific gastrointestinal permeability testing in children and adults. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;50:269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karhu E, Forsgård RA, Alanko L, Alfthan H, Pussinen P, Hämäläinen E, Korpela R. Exercise and gastrointestinal symptoms: running-induced changes in intestinal permeability and markers of gastrointestinal function in asymptomatic and symptomatic runners. Eur J Appl Physiol 2017;117:2519–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pires W, Veneroso CE, Wanner SP, Pacheco DAS, Vaz GC, Amorim FT, Tonoli C, Soares DD, Coimbra CC. Association between exercise-induced hyperthermia and intestinal permeability: a systematic review. Sports Med 2017;47:1389–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Wijck K, Wijnands KA, Meesters DMp, Boonen B, van Loon LJ, Buurman WA, Dejong CH, Lenaerts K, Poeze M. L-citrulline improves splanchnic perfusion and reduces gut injury during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:2039–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Man Angela L 1, Bertelli Eugenio 2, Rentini Silvia 3, Regoli Mari 2, Briars Graham 4, Marini Mario 3, Watson Alastair J M 5 Age-associated modifications of intestinal permeability and innate immunity in human small intestine. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015. October;129(7):515–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, Ockhuizen T, Schulzke JD, Serino M, Tilg H, Watson A, Wells JM. Intestinal permeability--a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014. November 18;14:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papathanasopoulos A, Camilleri M. Dietary fiber supplements: effects in obesity and metabolic syndrome and relationship to gastrointestinal functions. Gastroenterology 2010;138:65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.