Abstract

The trafficking of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) to different membrane compartments has recently emerged as being a critical determinant of the signaling profiles of activation. GPCRs, which share many structural and functional similarities, also share many mechanisms that traffic them between compartments. This sharing raises the question of how the trafficking of individual GPCRs is selectively regulated. Here, we will discuss recent studies addressing the mechanisms that contribute to selectivity in endocytic and biosynthetic trafficking of GPCRs.

Introduction

The regulation of signaling by membrane trafficking has traditionally been attributed to trafficking’s role in controlling the number of signaling receptors on the cell surface [1]. For G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs), the largest single family of signaling receptors [2], the removal of activated receptors from the cell surface by endocytosis and recovery of receptors on the surface by either recycling of internalized receptors or delivery of new receptors control the strength of response to extracellular ligands [3,4]. Recent studies, however, have highlighted more complex aspects of how trafficking regulates signaling. One is that GPCRs can signal from a variety of intracellular compartments [5,6].

Another is that mechanisms that regulate GPCR trafficking are heterogeneous, allowing selective control over the location and trafficking of individual GPCRs [3]. These aspects have highlighted a new idea that the primary role of trafficking might be to move specific GPCRs between specific signaling complexes on different membrane domains, as opposed to simply regulating cell surface receptors [7,8]. In this review, we will discuss recent studies on endocytic and biosynthetic trafficking of GPCRs, focusing on example mechanisms that provide specificity in the midst of shared mechanisms.

Endocytic trafficking

The mechanisms of GPCR endocytosis and postendocytic trafficking after receptor activation, which are common features of many GPCRs, have been exhaustively addressed in several reviews [3,9-11]. We will discuss recent findings on receptor interactions and signaling pathways that provide selectivity within these mechanisms.

Selectivity in endocytosis of GPCRs

How the endocytosis of GPCRs is individually controlled has been a long-standing question, considering that the general mechanism is shared broadly across most GPCRs [11]. Activated GPCRs undergo specific conformational changes that, in addition to catalyzing GTP exchange on G proteins, allow GPCR kinases to phosphorylate the receptor C-termini. These phosphorylated C-termini are recognized by arrestins, which act as adapters that link receptors to the clathrin endocytic machinery [12-14].

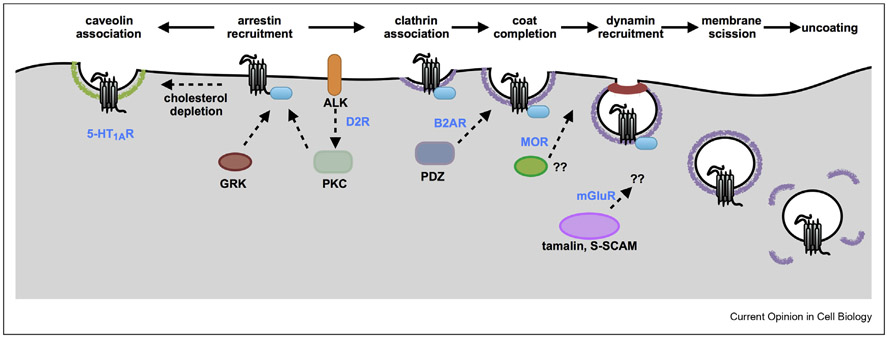

One aspect of this process that could be selective is receptor phosphorylation. Many GPCRs have multiple phosphorylation sites on its C-terminal tail, which are required for receptor internalization [15,16]. For example, in the mu-opioid receptor (MOR), a phosphorylation cluster within residues 375–379 is the primary mediator of endocytosis [17,18], which might be driven mainly by GRK2 in HEK293 cells [19]. C-terminal sites may be phosphorylated hierarchically by multiple kinases [20,21], suggesting that each GPCR could have a set of kinases that phosphorylate it and drives endocytosis. For example, the receptor tyrosine kinase anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) associates with the dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) but not the closely related dopamine D1 receptor. An inhibitor of ALK blocks internalization of D2R but not of D1R. ALK-mediated activation of protein kinase C γ (PKCγ) downstream of dopamine is required and sufficient for D2R internalization in HEK293 cells [22]. The exact ALK-dependent internalization mechanism is not clear, but PKCγ may influence the phosphorylation patterns of D2R and target interactions between D2R and arrestin.

For the vasopressin 2 receptor (V2R), differences in phosphorylation at specific residues tuned the strength of arrestin interactions and regulate endocytosis. Mutation of Ser 357 or Thr 360 to alanines reduced arrestin binding as measured by co-immunoprecipitation but still retained enough binding to be visualized as membrane recruitment by microscopy. This reduced binding in the case of Ser 357 mutation was still sufficient for qualitatively similar levels of V2R and arrestin localization to endosomes. In contrast, reduced binding in the case of Thr 360 mutation abolished arrestin localization to endosomes, although its effect on V2R endocytosis was not directly measured [23]. Similarly, a naturally occurring variant at Thr 282 for the angiotensin II receptor 1 induced a distinct conformation of arrestin upon binding, which was less stable but still supported endocytosis [24].

The second aspect of endocytosis that could be selective are “checkpoints” that exist after GPCR localization to endocytic domains (Figure 1). GPCR C-terminal tails contain specific sequences that interact with several components of the endocytic machinery. For example, a type I PDZ ligand on the C-terminus of the beta 2 adrenergic receptor indirectly links receptors to the actin cytoskeleton in clathrin-coated pits. This link delays the recruitment of dynamin, a GTPase that is required for membrane scission during endocytosis [25]. In contrast, PDZ-mediated interaction of mGluR1 and mGluR5, two metabotropic glutamate receptors, with the scaffold protein tamalin is essential for receptor endocytosis [26]. In this case, tamalin might link the receptors to motors via a scaffold protein S-SCAM, suggesting that it acts at a late step. An unrelated “bileucine” sequence on the C-terminal tail of MOR delays scission even after dynamin is recruited [27]. The same receptor might contain multiple discrete sequences that regulate endocytosis. The first intracellular loop of MOR contains specific lysines that are ubiquitinated by the ubiquitin ligase Smurf2. This ubiquitination, recognized by the endocytic accessory protein Epsin1, is required for endocytic scission [28]. For the protease-activated receptor 1, ubiquitination-dependent recruitment of Epsin1 and the endocytic adapter AP-2 can induce receptor endocytosis in the absence of arrestins [29]. The third intracellular loop of the beta 1 adrenergic receptor (B1AR) recruits endohilin, a BAR domain–containing protein that generates membrane curvature as part of the endocytic machinery, when linked to Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Endophilin, once recruited via interactions of the third loop with the endophilin SH3 domain, can generate membrane curvature on these vesicles [30]. Specific local protein interactions of individual GPCRs might therefore delay or facilitate their own endocytosis by modulating endocytic components.

Figure 1. GPCR endocytosis is regulated by selective mechanisms.

GPCR endocytosis from the plasma membrane can be regulated at multiple steps. The 5-HT1AR can switch between clathrin-dependent or caveolin-dependent endocytosis depending on cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane, which suggests that GPCR endocytosis can be regulated by the local membrane environment. GPCR interactions with arrestin, a shared endocytic adapter, could be regulated by the slate of kinases that determine the phosphorylation patterns on the GPCR C-termini. The GPCR C-termini and cytoplasmic loops contain additional sequences that regulate later steps in endocytosis by interacting with structural scaffold proteins such as PDZ proteins or tamalin. Although these mechanisms are still not fully understood, newer methods including high resolution live cell microscopy and single molecule tracking may help us decipher the interpay between these factors, GPCRs, and the endocytic machinery.

A third aspect is the selective interaction of GPCRs with membrane lipids. The third intracellular loop of the B1AR, described previously, electrostatically interacts with anionic phospholipids, which interfere with SH3 recruitment [30]. GPCRs might localize to microdomains, such as lipid rafts or caveolae on the surface, often in a regulated manner [31,32]. Activation of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) in pancreatic beta cells redistributes the receptors to membrane nanodomains that contain the lipid raft marker flotillin [33]. When cholesterol was depleted by methyl-β-cyclodextrin, GLP-1R failed to redistribute to nanodomains and to internalize. Receptor palmitoylation and different agonists regulated this redistribution, raising the possibility that the process could be regulated by signaling. The role that cholesterol interactions play could be specific for each GPCR. When cholesterol was depleted by statin drugs, 5-HT1A receptors (5-HT1AR) internalized, but the pathway switched from clathrin-mediated to caveolin-mediated endocytosis [34]. Interestingly, when cholesterol was depleted to similar levels using methyl-β-cyclodextrin, 5-HT1AR still internalized via a clathrin-mediated pathway, although postendocytic sorting was altered [35].

Several cholesterol-binding motifs, termed cholesterol consensus motifs, cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus (CRAC) motifs, or CARC motifs when they exist in reverse, have been identified in GPCRs [36,37]. In many cases, the motifs have been functionally confirmed as being required for normal GPCR trafficking. A recent analysis of structural data across available GPCR structures, however, concluded that CRAC motifs are not predictive of cholesterol binding [38]. One potential way to reconcile these observations is that the motifs reflect potential hot spots of interactions [39]. Another way is to consider that lipid binding might be hierarchical, where allosteric changes caused by lipid binding on one site increases or decreases the affinity of other lipid-binding sites. In this context, it is important to note that the structural informatics [38] was based largely on structures generated under conditions using synthesized lipids or detergents, which are different from in vivo environments where a full complement of lipids and proteins are present. Overall, much less is known about how lipids interact with GPCRs, compared with how proteins interact with GPCRs.

Selectivity in postendocytic trafficking of GPCRs

Internalized GPCRs typically have two fates once they are internalized and trafficked to the endosomal system. They may recycle back to the cell surface or may be degraded in the lysosome [9,10]. Nutrient receptors such as the transferrin receptor are recycled largely by bulk membrane flow [40], but GPCR recycling requires specific sequences on receptors. These sequences both restrict GPCRs from recycling by bulk flow and direct GPCRs to sequence-dependent recycling or degradation [3,10]. Mutating two PKA phosphorylation sites on B2AR converts the receptor into a bulk recycling protein, suggesting that bulk sorting is hierarchically above sorting between sequence-dependent recycling and degradation [41]. At present, the factors that restrict GPCRs from accessing the bulk recycling pathway are not known.

Spatial segregation of GPCRs in the endocytic pathway

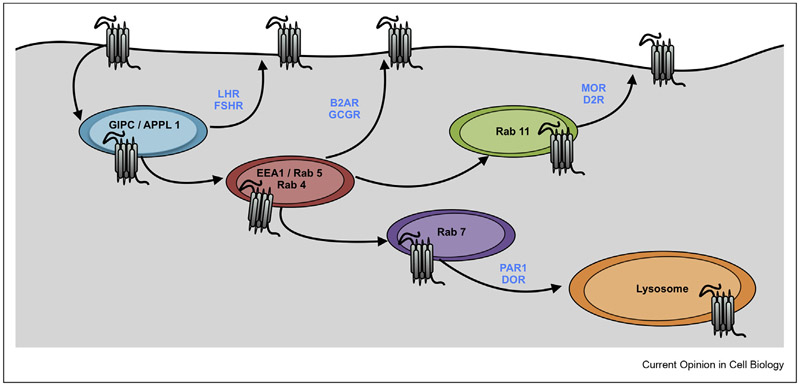

The endolysosomal system is now recognized as a complex mix of partially overlapping membrane systems that constantly mature along the endocytic pathway (Figure 2). The current model is that endocytosed GPCRs pass through the very early endosome (VEE) to the early endosome (EE). The VEE is marked by APPL1 but devoid of Rab5 and EEA1, which mark the EE. The luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) and the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) are localized to the VEE after activation [42]. Many other GPCRs such as the prototypical B2AR are localized mainly to EE after activation [43].

Figure 2. A sequential model for GPCR sorting throughout the endolysosomal network.

After internalization from the plasma membrane, GPCRs are sequentially transported through the VEE and EE, at which point they are sorted into the RE or the late endocytic/degradative pathway. These compartments are marked by specific biochemical components. GPCRs can interact with specific recycling trafficking proteins in these compartments that direct them to the recycling pathway. Selected examples of markers for compartments and GPCRs that recycle from them are shown. It is important to note that these compartments are depicted separately to denote where the majority of components are at steady state. In vivo, these compartments are likely to overlap significantly because of dynamic membrane exchange and maturation.

The steady-state segregation of GPCRs in distinct compartments likely represents receptor recycling from that compartment. LHR and FSHR are rapidly recycled from the VEE via interactions of receptor C-termini with the PDZ-containing protein GIPC. Disrupting PDZ-GIPC interactions decreases recycling and shifts the steady state distribution of LHR to the EE and later compartments [42]. Similarly, B2AR is recycled from the EE by interactions of a PDZ ligand on its C-terminal tail with proteins in the actin-sorting nexin-retromer tubular domains of endosomes. Disrupting PDZ interactions decreases recycling and drives B2AR into the late endosomal pathway to be degraded [44]. For the atypical chemokine receptor 3, overexpression of RAMP3, a PDZ-containing member of a family of single-transmembrane proteins that associate with GPCRs, and NSF qualitatively changes receptor localization from Rab7 late endosomes to Rab4 early endosomes, after an hour of agonist treatment and 4 h of washout [45]. GPCRs in the EE may also be trafficked to a dedicated recycling endosome marked by Rab11, from which they can recycle. Receptor interactions with these specific components and localization depend on a slate of posttranslational modifications on the receptor, such as phosphorylation or ubiquitination [15].

Regulation of GPCR sorting by signaling

Signaling pathways downstream of the same receptor (homologous) or other receptors (heterologous) could selectively regulate the rates of sorting and recycling of GPCRs by inducing posttranslational modifications on select GPCRs. B2AR activity reduces the rate of B2AR recycling via receptor phosphorylation by PKA [41]. MOR activity, however, increases MOR recycling independent of PKA via phosphorylation at Ser 363 and Thr 370 by PKC downstream of receptor activation [46]. The same sites on MOR can also be phosphorylated by PKC downstream of neurokinin-1 signaling to increase MOR recycling and resensitization, allowing for cross-talk between these signaling pathways [47]. For the chemokine receptor CXCR4, however, PKC activation drives receptor degradation, suggesting that the same signaling pathway can affect different receptors differently [48]. PKC phosphorylation of CXCR4 at Ser 324/325 recruits the ubiquitin ligase AIP4. PKC was sufficient but not necessary for CXCR4 degradation, suggesting that another kinase might phosphorylate one of these residues and recruit AIP4 [48]. Importantly, postendocytic sorting mechanisms might be leveraged by physiological systems to fine tune the effects of receptor activation. Two endogenous ligands regulated the postendocytic fate of the kappa opioid receptor (KOR) differently [49]. Dynorphin B caused KOR to rapidly recycle via Rab11, whereas Dynorphin A caused KOR to be degraded in the lysosomes. Interestingly, KOR localized to the lysosomes was able to signal from there, causing a sustained signaling compared with when KOR was recycled.

Biosynthetic trafficking

The folding and export of GPCRs from the endoplasmic reticulum is regulated by a variety of interacting proteins and by exogenous drugs that act as chaperones [50,51]. In contrast, whether and how GPCR trafficking after ER export is regulated is less well understood. In this section, we will discuss recent data describing the heterogeneous mechanisms that regulate GPCRs transport from compartments after ER export (Figure 3).

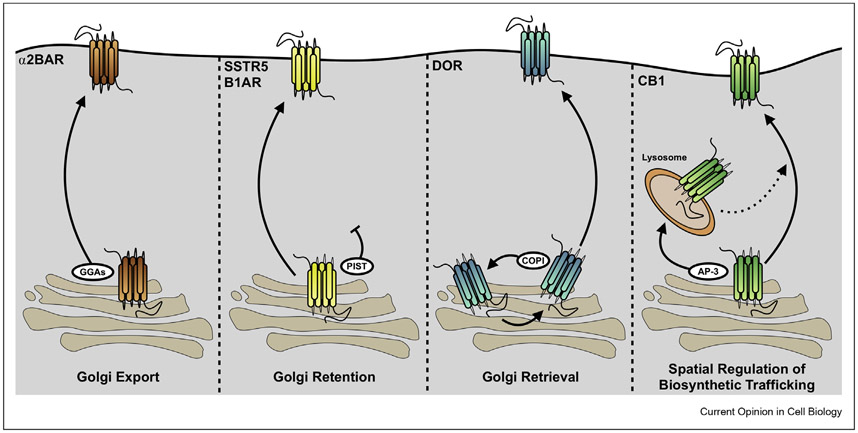

Figure 3. Post-Golgi trafficking of GPCRs can be regulated by diverse mechanisms.

Example pathways by which GPCR export can be regulated. GPCRs such as the α-2B adrenergic receptor and angiotensin II receptor type I are exported by interactions with GGA proteins. SSTR5 and B1AR are retained in the Golgi via interactions with PIST, a PDZ-binding protein. DOR, on the other hand, is kept in the Golgi by constant retrieval via COPI interactions. CB1 is routinely trafficked to lysosomal compartments via AP-3 interactions, and disrupting these interactions redirects receptors to the plasma membrane. It is possible that additional pathways exist and that these pathways and interactions are relevant to different receptors in different cell types based on expression of components.

Many “general” trafficking proteins, such as small monomeric GTPases and their interactors, have been implicated in GPCR export from the Golgi apparatus [50]. For example, the trafficking of α2B-adrenergic receptors depends on the Golgi-localizing, gamma-adaptin ear homology domain, ARF-binding (GGA) family of proteins and Rab26 [52-54]. GGA1, 2, and 3 all interact with the third intracellular loop of α2B-adrenergic receptor, although by different mechanisms. Depleting any one of the GGAs causes a partial reduction in surface delivery of α2B-adrenergic receptor, suggesting that each of them is partially required. GGA3 binds an RRR motif in the loop, whereas GGA1 and 2 do not. GGA3 depletion reduces export also of α2C-adrenergic receptors, but not of α2A-adrenergic receptors. Rab26 also binds the same intracellular loop in a GTP-dependent manner, regulated by the putative GAP TBC1D6 [54]. Unlike for GGA3, linear motifs on the receptor required for GGA1, GGA2, or Rab26 could not be identified by deletion studies, suggesting that they may bind a multipartite motif based on a specific conformation of the loop. Interestingly, an alternatively spliced variant of GGA1 lacks the hinge region of GGA1 that interacts with the α2B-adrenergic receptor, suggesting that isoform expression could provide selectivity [55]. As another example, the export of PAR2 from the Golgi requires the activation of protein kinase D (PKD). In this case, PKD is activated by Gbγ translocation to the Golgi after PAR activation, causing a feedback loop for repopulating the surface after receptor downregulation [56]. Gbγ and PKD are required for general TGN export [57], and whether other cargo molecules are also regulated downstream of PAR2 activation is not clear. Nevertheless, it is clear that some GPCRs use the predominant TGN export pathways to traffic to the cell surface.

Selective mechanisms that localize specific GPCRs without affecting trafficking in general have also been recently identified. The Leukotriene B4 Receptor Type 2 (BLT2) contains an unidentified sequence on its C-terminal tail, which enables it to interact with the scaffold protein LIN7C [58]. A truncated BLT2 without this tail accumulates in the Golgi. But when LIN7C is depleted, BLT2 accumulates in intracellular compartments not restricted to the Golgi. In contrast, overexpression of the PDZ protein PIST localizes somatostatin receptor 5 and B1AR to the Golgi [59,60], presumably by interacting with the C-terminal PDZ ligand on the receptor.

The delta opioid receptor (DOR) provides a unique and interesting example of a GPCR whose Golgi localization is cell type specific and highly regulated. In neurons, newly synthesized DOR is retained in intracellular compartments that overlap with the Golgi, but in nonneuronal cells, DOR is efficiently expressed on the surface [61,62]. This Golgi localization is highly regulated by signaling. In the neuroendocrine PC12 cells, DOR is normally expressed at the cell surface, but a short exposure to Nerve Growth Factor, which inhibits phosphoinositide 3 kinase class 2 and reduces PI(3,4)P levels, induces Golgi localization of DOR [63]. The current model for this retention is that in neurons or in NGF-treated PC12 cells, DOR is constantly retrieved to earlier compartments in the Golgi by regulated interactions with the coatomer protein 1 (COPI) complex. DOR contains two atypical COPI-binding RXR motifs in its C-terminal tail [64], which are required and sufficient for regulated Golgi localization. DOR contains additional canonical COPI-binding motifs in the second and third intracellular loops [65], which could contribute to a basal level of intracellular DOR. At present, whether these interactions are regulated is not known.

In contrast to DOR, endogenous cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) is localized to the late endosomal compartments and axonal surface in hippocampal neurons [66,67]. The late endosomal localization could be because of the shunting of CB1R in the TGN to an adaptor protein 3δ–mediated export pathway [66]. The deletion of helix 9 (H9) in the C-terminus caused CB1R to lose axonal polarization, but it was still delivered to the surface [67]. This suggests that the receptor might be able to access multiple export pathways out of the TGN. The mechanism by which H9 regulates export is not known. The amphipathic nature of the helix might play a role, as amphipathicity of H8 was required for the export of apelin receptor from intracellular compartments and for efficient surface expression [68].

Outside of specific adapters and interacting proteins, receptor oligomerization is an exciting possibility that could provide specificity to trafficking. For example, the transport protein RTP4 interacts with MOR and DOR and selectively increases expression of heteromers on the surface [69], without affecting individually expressed MOR and DOR or CB1R or dopamine 2 receptors [70]. Overall, the diversity of mechanisms that regulate Golgi retention and export suggest that GPCR delivery via the secretory pathway could be selectively regulated for individual GPCRs.

Conclusions

The subcellular location of GPCRs could be a master regulator of GPCR function, as the list of GPCRs capable of signaling from intracellular compartments is rapidly growing [5-7]. Modulating signals from specific compartments, by either relocating receptors to the plasma membrane [47,61] or specifically targeting signaling from endosomes [71], has clear effects on signaling and behavior. As we develop sophisticated tools to study both the mechanisms of selective trafficking and localized signaling of GPCRs [72-74], we will be able to generate a more precise understanding of spatial patterns of signaling for each member of this important family of signaling receptors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs Aditya Kumar and Lakshmi Devi for valuable discussions. The authors also thank many colleagues in the GPCR field with whom they have had continued discussions, all of whose work could not be cited or discussed due to constraints in space and scope. J.M.K. was supported by NIH T32-GM007315, J.L. was supported by NIH T32-GM007767, and M.A.P. was supported by NIH GM117425 and by NSF 1935926.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

* * of outstanding interest

- 1.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M: Endocytosis and signalling: inter-twining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10:609–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ: Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002, 3:639–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanyaloglu AC, Zastrow MV: Regulation of GPCRs by endocytic membrane trafficking and its potential implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2008, 48:537–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausdorff WP, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ: Turning off the signal: desensitization of β-adrenergic receptor function. Faseb J 1990, 4:2881–2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sposini S, Hanyaloglu AC: Evolving view of membrane trafficking and signaling systems for G protein-coupled receptors. Endocytos Signal 2018:273–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobingier BT, von Zastrow M: When trafficking and signaling mix: how subcellular location shapes G protein-coupled receptor activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Traffic 2019, 20:130–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crilly SE, Puthenveedu MA: Compartmentalized GPCR signaling from intracellular membranes. J Membr Biol 2020, 10.1007/s00232-020-00158-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calebiro D, Koszegi Z: The subcellular dynamics of GPCR signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2019, 483:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowman SL, Puthenveedu MA: Postendocytic sorting of adrenergic and opioid receptors: new mechanisms and functions. Pro Mol Biol Trans Sci 2015, 132:189–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahouth SW, Nooh MM: Barcoding of GPCR trafficking and signaling through the various trafficking roadmaps by compartmentalized signaling networks. Cell Signal 2017, 36: 42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinberg ZY, Puthenveedu MA: Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling by plasma membrane organization and endocytosis. Traffic 2019, 20:121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian X, Kang DS, Benovic JL: β-arrestins and G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2014, 219: 173–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV: The structural basis of the arrestin binding to GPCRs. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2019, 484:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caron MG, Barak LS: A brief history of the β-arrestins. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1957:3–8. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patwardhan A, Cheng N, Trejo J: Post-translational modifications of G protein–coupled receptors control cellular signaling dynamics in space and time. Pharmacol Rev 2021, 73:120–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV: GPCR signaling regulation: the role of GRKs and arrestins. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau EK, Trester-Zedlitz M, Trinidad JC, Kotowski SJ, Krutchinsky AN, Burlingame AL, von Zastrow M: Quantitative encoding of the effect of a partial agonist on individual opioid receptors by multisite phosphorylation and threshold detection. Sci Signal 2011, 4. ra52–ra52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arttamangkul S, Leff ER, Koita O, Birdsong WT, Williams JT: Separation of acute desensitization and long-term tolerance of μ-opioid receptors is determined by the degree of C-terminal phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 2019, 96:505–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouley RA, Weinberg ZY, Waldschmidt HV, Yen YC, Larsen SD, Puthenveedu MA, Tesmer JJ: A new paroxetine-based GRK2 inhibitor reduces internalization of the μ-opioid receptor. Mol Pharmacol 2020, 97:392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Just S, Illing S, Trester-Zedlitz M, Lau EK, Kotowski SJ, Miess E, Mann A, Doll C, Trinidad JC, Burlingame AL, von Zastrow M: Differentiation of opioid drug effects by hierarchical multi-site phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 2013, 83: 633–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duarte ML, Devi LA: Post-translational modifications of opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci 2020, 43:417–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.He D, Lasek AW: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase regulates internalization of the dopamine D2 receptor. Mol Pharmacol 2020, 97:123–131.This study showed that an inhibitor of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) blocks internalization of D2R but not of D1R. In addition, this article showed that D2R internalization was regulated by ALK-mediated activation of protein kinase C γ

- *23.Dwivedi-Agnihotri H, Chaturvedi M, Baidya M, Stepniewski TM, Pandey S, Maharana J, Srivastava A, Caengprasath N, Hanyaloglu AC, Selent J, Shukla AK: Distinct phosphorylation sites in a prototypical GPCR differently orchestrate β-arrestin interaction, trafficking, and signaling. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eabb8368.This careful mutational study showed how different phosphorylation sites on the human vasopressin receptor differentially recruit arrestin and how these sites are critical for arrestin localization to endosomes after receptor activation.

- *24.Cao Y, Kumar S, Namkung Y, Gagnon L, Cho A, Laporte SA: Angiotensin II type 1 receptor variants alter endosomal receptor–β-arrestin complex stability and MAPK activation. J Biol Chem 2020, 295:13169–13180.This study showed how a T282M variant of the angiotensin II receptor I (ATR1) induced a distinct arrestin conformation upon receptor binding after activation. This variant failed to recruit arrestins to endosomes and recycled faster to the surface after endocytosis. This and the previous study together support the view that specific phosphorylation patterns could allow receptors to engage arrestins differently.

- 25.Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M: Cargo regulates clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Cell 2006, 127:113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandey S, Ramsakha N, Sharma R, Gulia R, Ojha P, Lu W, Bhattacharyya S: The post-synaptic scaffolding protein Tamalin regulates ligand-mediated trafficking of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Biol Chem 2020. jbc-RA119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberg ZY, Zajac AS, Phan T, Shiwarski DJ, Puthenveedu MA: Sequence-specific regulation of endocytic lifetimes modulates arrestin-mediated signaling at the μ opioid receptor. Mol Pharmacol 2017, 91:416–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry AG, Hislop JN, Grove J, Thorn K, Marsh M, von Zastrow M: Regulation of endocytic clathrin dynamics by cargo ubiquitination. Dev Cell 2012, 23:519–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen B, Dores MR, Grimsey N, Canto I, Barker BL, Trejo J: Adaptor protein complex-2 (AP-2) and epsin-1 mediate protease-activated receptor-1 internalization via phosphorylation-and ubiquitination-dependent sorting signals. J Biol Chem 2011, 286:40760–40770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **30.Mondal S, Narayan KB, Powers I, Botterbusch S, Baumgart T: Endophilin recruitment drives membrane curvature generation through coincidence detection of GPCR loop interactions and negative lipid charge. J Biol Chem 2021:100–140.This article shows that the third intracellular loops of GPCRs can bind the SH3 domain of endophilin and recruit the protein to membranes to generate membrane curvature. Anionic lipids inhibit this recruitment. GPCRs might therefore directly recruit endocytic components based on the immediate environment.

- 31.Patel HH, Murray F, Insel PA: G-protein-coupled receptor-signaling components in membrane raft and caveolae microdomains. Protein-Protein Interactions as New Drug Targets 2008:167–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Briddon SJ, Kilpatrick LE, Hill SJ: Studying GPCR pharmacology in membrane microdomains: fluorescence correlation spectroscopy comes of age. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018, 39:158–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **33.Buenaventura T, Bitsi S, Laughlin WE, Burgoyne T, Lyu Z, Oqua AI, Norman H, McGlone ER, Klymchenko AS, Corrêa IR Jr, Walker A: Agonist-induced membrane nanodomain clustering drives GLP-1 receptor responses in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000097.This study showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) expressed in pancreatic beta cells redistributed to flotillin-containing nanodomains after receptor activation. This redistribution required cholesterol and GLP-1R palmitoylation and was regulated by different agonists.

- **34.Kumar GA, Chattopadhyay A: Statin-induced chronic cholesterol depletion switches GPCR endocytosis and trafficking: insights from the serotonin1A receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020, 11:453–465.This study showed that cholesterol depletion by statin drugs switched agonist-mediated 5-HT1A receptor endocytosis to caveolin-mediated endocytosis from clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Together with the previous and the next studies, this study shows that cholesterol plays complex roles in GPCR endocytosis.

- 35.Kumar GA, Chattopadhyay A: Membrane cholesterol regulates endocytosis and trafficking of the serotonin1A receptor: insights from acute cholesterol depletion. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2021:158882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fantini J, Di Scala C, Baier CJ, Barrantes FJ: Molecular mechanisms of protein-cholesterol interactions in plasma membranes: functional distinction between topological (tilted) and consensus (CARC/CRAC) domains. Chem Phys Lipids 2016, 199:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fatakia SN, Sarkar P, Chattopadhyay A: A collage of cholesterol interaction motifs in the serotonin1A receptor: an evolutionary implication for differential cholesterol interaction. Chem Phys Lipids 2019, 221:184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taghon GJ, Rowe JB, Kapolka NJ, Isom DG: Predictable cholesterol binding sites in GPCRs lack consensus motifs. Structure 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarkar P, Chattopadhyay A: Cholesterol interaction motifs in G protein-coupled receptors: slippery hot spots? Wiley Interdisciplinary Rev: Sys Biol Med 2020, 12, e1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayor S, Presley JF, Maxfield FR: Sorting of membrane components from endosomes and subsequent recycling to the cell surface occurs by a bulk flow process. J Cell Biol 1993, 121:1257–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vistein R, Puthenveedu MA: Reprogramming of G protein-coupled receptor recycling and signaling by a kinase switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110:15289–15294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jean-Alphonse F, Bowersox S, Chen S, Beard G, Puthenveedu MA, Hanyaloglu AC: Spatially restricted G protein-coupled receptor activity via divergent endocytic compartments. J Biol Chem 2014, 289:3960–3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puthenveedu MA, Lauffer B, Temkin P, Vistein R, Carlton P, Thorn K, Taunton J, Weiner OD, Parton RG, von Zastrow M: Sequence-dependent sorting of recycling proteins by actin-stabilized endosomal microdomains. Cell 2010, 143:761–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao TT, Deacon HW, Reczek D, Bretscher A, von Zastrow M: A kinase-regulated PDZ-domain interaction controls endocytic sorting of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nature 1999, 401:286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackie DI, Nielsen NR, Harris M, Singh S, Davis RB, Dy D, Ladds G, Caron KM: RAMP3 determines rapid recycling of atypical chemokine receptor-3 for guided angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116:24093–24099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunselman JM, Zajac AS, Weinberg ZY, Puthenveedu MA: Homologous regulation of mu opioid receptor recycling by Gbγ, protein kinase C, and receptor phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 2019, 96:702–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowman SL, Soohoo AL, Shiwarski DJ, Schulz S, Pradhan AA, Puthenveedu MA: Cell-autonomous regulation of Mu-opioid receptor recycling by substance P. Cell Rep 2015, 10: 1925–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caballero A, Mahn SA, Ali MS, Rogers MR, Marchese A: Heterologous regulation of CXCR4 lysosomal trafficking. J Biol Chem 2019, 294:8023–8036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunselman JM, Gupta A, Devi LA, Puthenveedu MA: Compartment-specific opioid receptor signaling is selectively modulated by dynorphin subtypes. bioRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang M, Wu G: Mechanisms of the anterograde trafficking of GPCRs: regulation of AT1R transport by interacting proteins and motifs. Traffic 2019, 20:110–120 (Copenhagen, Denmark). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doly S, Marullo S: Gatekeepers controlling GPCR export and function. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36:636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang M, Huang W, Gao J, Terry AV, Wu G: Regulation of α2B-adrenergic receptor cell surface transport by GGA1 and GGA2. Sci Rep 2016, 6:37921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang M, Davis JE, Li C, Gao J, Huang W, Lambert NA, Terry AV Jr, Wu G: GGA3 interacts with a G protein-coupled receptor and modulates its cell surface export. Mol Cell Biol 2016, 36:1152–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **54.Wei Z, Zhang M, Li C, Huang W, Fan Y, Guo J, Khater M, Fukuda M, Dong Z, Hu G, Wu G: Specific TBC domain-containing proteins control the ER-golgi-plasma membrane trafficking of GPCRs. Cell Rep 2019, 28:554–566. e4.This article used an siRNA-mediated knockdown screen to identify the TBC proteins required for the surface delivery of adrenergic receptors. TBC1D6 was identified as a Rab26 GAP that modulated post-Golgi trafficking of the receptor.

- 55.Zhang M, Xu X, Li C, Huang W, Xu N, Wu G: A naturally occurring splice variant of GGA1 inhibits the anterograde post-golgi traffic of α2B-adrenergic receptor. Sci Rep 2019, 9:10378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao P, Pattison LA, Jensen DD, Jimenez-Vargas NN, Latorre R, Lieu T, Jaramillo JO, Lopez-Lopez C, Poole DP, Vanner SJ, Schmidt BL, Bunnett NW: Protein kinase D and Gbγ mediate sustained nociceptive signaling by biased agonists of protease-activated receptor-2. J Biol Chem 2019, 294: 10649–10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Díaz Añel AM, Malhotra V: PKCeta is required for beta1-gamma2/beta3gamma2- and PKD-mediated transport to the cell surface and the organization of the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol 2005, 169:83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hara T, Saeki K, Jinnouchi H, Kazuno S, Miura Y, Yokomizo T: The c-terminal region of BLT2 restricts its localization to the lateral membrane in a LIN7C-dependent manner. Faseb J 2021, 35, e21364. official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wente W, Stroh T, Beaudet A, Richter D, Kreienkamp HJ: Interactions with PDZ domain proteins PIST/GOPC and PDZK1 regulate intracellular sorting of the somatostatin receptor subtype 5. J Biol Chem 2005, 280:32419–32425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koliwer J, Park M, Bauch C, von Zastrow M, Kreienkamp HJ: The golgi-associated PDZ domain protein PIST/GOPC stabilizes the β1-adrenergic receptor in intracellular compartments after internalization. J Biol Chem 2015, 290:6120–6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shiwarski DJ, Tipton A, Giraldo MD, Schmidt BF, Gold MS, Pradhan AA, Puthenveedu MA: A PTEN-regulated checkpoint controls surface delivery of δ opioid receptors. J Neurosci 2017, 37:3741–3752. the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gendron L, Cahill CM, von Zastrow M, Schiller PW, Pineyro G: Molecular pharmacology of δ-opioid receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2016, 68:631–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shiwarski DJ, Darr M, Telmer CA, Bruchez MP, Puthenveedu MA: PI3K class II α regulates δ-opioid receptor export from the trans-Golgi network. Mol Biol Cell 2017, 28:2202–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shiwarski DJ, Crilly SE, Dates A, Puthenveedu MA: Dual RXR motifs regulate nerve growth factor-mediated intracellular retention of the delta opioid receptor. Mol Biol Cell 2019, 30:680–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.St-Louis É, Degrandmaison J, Grastilleur S, Génier S, Blais V, Lavoie C, Parent JL, Gendron L: Involvement of the coatomer protein complex I in the intracellular traffic of the delta opioid receptor. Mol Cell Neurosci 2017, 79:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rozenfeld R, Devi LA: Regulation of CB1 cannabinoid receptor trafficking by the adaptor protein AP-3. Faseb J 2008, 22: 2311–2322. official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *67.Fletcher-Jones A, Hildick KL, Evans AJ, Nakamura Y, Wilkinson KA, Henley JM: The C-terminal helix 9 motif in rat cannabinoid receptor type 1 regulates axonal trafficking and surface expression. eLife 2019, 8, e44252.This study uses time-lapse imaging to show that axonal polarized localization of CB1 requires the C-terminal Helix-9 (H9). Deletion of H9 facilitates CB1 trafficking of CB1 to dendritic surfaces and causes higher internalization and weakened G-protein signaling.

- 68.Pandey A, LeBlanc DM, Parmar HB, Phạm TTT, Sarker M, Xu L, Duncan R, Liu XQ, Rainey JK: Structure, amphipathy, and topology of the membrane-proximal helix 8 influence apelin receptor plasma membrane localization. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2019, 1861:183036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Décaillot FM, Rozenfeld R, Gupta A, Devi LA: Cell surface targeting of mu-delta opioid receptor heterodimers by RTP4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105:16045–16050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fujita W, Yokote M, Gomes I, Gupta A, Ueda H, Devi LA: Regulation of an opioid receptor chaperone protein, RTP4, by morphine. Mol Pharmacol 2019, 95:11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jimenez-Vargas NN, Gong J, Wisdom MJ, Jensen DD, Latorre R, Hegron A, Teng S, DiCello JJ, Rajasekhar P, Veldhuis NA, Carbone SE, Yu Y, Lopez-Lopez C, Jaramillo-Polanco J, Canals M, Reed DE, Lomax AE, Schmidt BL, Leong KW, Vanner SJ, … Poole DP: Endosomal signaling of delta opioid receptors is an endogenous mechanism and therapeutic target for relief from inflammatory pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117:15281–15292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calebiro D, Grimes J: G protein–coupled receptor pharmacology at the single-molecule level. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2020, 60:73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Halls ML, Canals M: Genetically encoded FRET biosensors to illuminate compartmentalised GPCR signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018, 39:148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maziarz M, Park JC, Leyme A, Marivin A, Garcia-Lopez A, Patel PP, Garcia-Marcos M: Revealing the activity of trimeric G-proteins in live cells with a versatile biosensor design. Cell 2020, 182:770–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]