SUMMARY

Background:

Malignant glioma is the most common and lethal primary brain tumor, with dismal survival rates and no effective treatment. We examined the safety and therapeutic potential of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7, an engineered oncolytic adenovirus delivered by neural stem cells (NSCs), in patients with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma.

Methods:

A first-in-human, open-label, phase 1, dose-escalation clinical trial was conducted to determine the maximal tolerated dose of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7, following a 3+3 design. Patients with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas (WHO Grade III or IV), confirmed by histological testing, were recruited. After neurosurgical resection, NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 was injected into the walls of the resection cavity. The first patient cohort received the first dose level starting at 6.25×1010 viral particles (vp) administered via 50 million NSCs, followed by the second patient cohort with the second dose level of 1.25×1011 vp administered via 100 million NSCs, and the third cohort received 1.875×1011 vp administered via 150 million NSCs. No further dose escalation was planned. Within 10–14 days, treatment with temozolomide and radiotherapy was initiated. Assessment was done through medical history, imaging, blood samples, and chemistry values that were collected at screening and follow-up. Tissue analysis for cytokines and immune infiltrates was also performed. Primary endpoints were safety and tolerability. Secondary endpoints included the estimation of survival outcomes in patients, and the evaluation of whether clinical outcomes correlated with the extent of the immune response. All analyses were done in all patients who were included in the trial and received the study treatment and were not excluded from the study. Recruitment is complete and the trial is finished. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03072134.

Findings:

Between April 24, 2017 and November 13, 2019, 12 patients with newly diagnosed, malignant gliomas were recruited and included in the safety analysis. The median follow-up was 18 months (IQR 14–22). Histopathological evaluation identified 11 (92%) of 12 patients with glioblastoma and one (8%) of 12 patients with anaplastic astrocytoma. Treatment was safe as no formal dose-limiting toxicity was reached. One patient developed viral meningitis (grade 3) due to the inadvertent injection of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 into the lateral ventricle. Post-mortem tissue exploration showed that NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 was effectively cleared from the brain. There were no treatment related deaths. The median progression-free survival and overall survival were 9.05 months (95% CI 8.54, NA) and 18.4 months (95% CI 15.7, NA), respectively.

Interpretation:

NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 elicited an immune-mediated anti-glioma response and showed promising survival outcomes, especially in patients with MGMT unmethylated tumors. Exploratory immunological results support continued investigation of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 with multiple injections through an intracranial catheter and/or its combination with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in a higher phase trial with a larger cohort of patients.

INTRODUCTION

High-grade malignant gliomas are the most common and lethal primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors in adults. Despite aggressive therapeutic regimens that comprise neurosurgical resection, radiation, and chemotherapy, median survival time in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma ranges from 14 to 21 months.1,2 The presence of aberrant chemo- and radio-resistant glioma stem cells within the tumor tissue contributes to patient relapse and poor survival outcomes,3 whereby the median survival time upon tumor recurrence is typically 9–11 months.4,5 As such, a dynamic approach that targets dispersed tumor cells, as well as resistant glioma stem cells, without disrupting the delicate neural architecture in the brain is necessary for effective treatment.6 Here, we examined the safety and therapeutic potential of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7, an engineered oncolytic adenovirus delivered by neural stem cells (NSCs), in patients with high-grade malignant gliomas.

Oncolytic adenoviral therapy is a promising therapeutic approach in malignant glioma due to its direct viral oncolytic effects and its ability to elicit an immune response. It has been proven to be safe in patient settings.7,8 Nevertheless, oncolytic viruses suffered from poor distribution and spread through the tumor mass and had limited abilities to effectively cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

NSCs are multipotent progenitor cells that originate from the developing and adult CNS.9 Preclinical experiments show their inherent ability to cross the BBB, distribute within the tumor bed, surround the tumor border, and migrate in the brain parenchyma to target glioma cells.10 In addition, the tumor-tropism of NSCs can be employed to deliver a therapeutically relevant molecule across the BBB.11

In previous work, we engineered an oncolytic adenovirus, CRAd-S-pk7, by incorporating a survivin promoter that drives replicative essential E1A gene expression and modifying the Ad5 fiber protein through the incorporation of a polylysine sequence (pk7).12 These alterations enhanced viral replication and targeting of glioma cells, which improved anti-tumor activity and increased survival in vivo.12,13 Using an NSC cell line, HB1.F3.CD21, which is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a cell carrier for human clinical trials,14 we effectively delivered a therapeutic payload of CRAd-S-pk7 in the experimental glioblastoma model.15 This approach combined the tumor tropism of NSCs with the enhanced ability of CRAd-S-pk7 to target chemo- and radio-resistant glioma stem cells.16 Preclinical work showed that NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 increased median survival by up to 50% compared to mice that were treated by the oncolytic virus alone.15 In addition, NSCs were capable of migrating throughout the brain and successfully handing off the therapeutic payload of CRAd-S-pk7 to targeted glioma cells.15 These findings warranted the translation of this therapeutic approach to the clinical setting.

In this work, we conducted a first-in-human, phase 1 clinical trial to determine the safety, identify therapeutic potential, and assess the immunological effect of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 in patients with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This study was an open label, phase 1, dose-escalation clinical trial that followed a 3+3 design. It was primarily conducted at the Northwestern Memorial Hospital (Chicago, IL 60611), with a secondary site at the City of Hope National Medical Center (Duarte, CA 91010).

We enrolled patients with newly diagnosed high-grade malignant glioma (WHO grade III or IV), confirmed through clinical and radiological evaluation. Pathological confirmation of malignant glioma was made at the time of resection on frozen section by a neuropathologist prior to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. Diagnoses made through frozen section analysis were later confirmed through permanent section analysis. Patients were planned to receive standard chemo-radiotherapy and their tumors had to be accessible for injection. Eligible patients were older than 18 years of age and had a Karnofsky performance scale score ≥ 70. Participants had adequate organ and bone marrow function within 28 days prior to registration, as defined by an SGOT < 3x upper limit of normal, serum creatinine < 2mg/dl, platelets >100,000/mm3, and WBC > 3000/mm3. Further baseline evaluations comprised panels for hematology, coagulation, and serum chemistry, a urinalysis with microscopy, an ECG, RCR testing, and viral shedding. Included participants were also able to undergo a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and provide written informed consent (appendix p. 38).

Patients were excluded if the tumor invaded the ventricular system, received prior radiation therapy or other experimental therapy, or were taking immunosuppressive medications (other than corticosteroids) within 28 days of the surgical procedure. Patients with prior or ongoing liver disease (cirrhosis, active hepatitis B or C), or known HIV infection were also excluded. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the trial protocol (appendix p. 38).

City of Hope provided the HB1.F3.CD21 NSCs for the clinical trial. CRAd-S-pk7 was produced and loaded into HB1.F3.CD21 cells at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Vector Production Facility, in accordance with current Good Manufacturing Practice for Phase 1 investigational drugs. Regulatory approvals were obtained from the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the local institutional research ethics committees (FDA IND 17365). The study was done in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. This trial was conducted in compliance with the Data Safety Monitoring Plan of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. A Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) was instituted to review any complications arising from the proposed therapy prior to the enrollment of new patients. In addition, the study abided by the safety reporting regulations, as set forth in the Code of Federal Regulations. All protocol amendments were approved by the trial sponsor and the DSMB. This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03072134.

Procedures

Patients with resectable disease received NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection into the tumor bed after surgical resection. Pathologic confirmation of a malignant glioma had to be made at the time of surgery prior to injection. Freehand injections of 100 μL of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 were performed in up to ten sites in the wall of the resection cavity. The sites were at least 1 cm apart and were selected by the surgeon to avoid injections into adjacent motor or speech cortices, leakage into cerebral ventricles, or spillage into the subarachnoid space. The dose-escalation phase started with an initial three patients enrolled per dose level, and a further three patients recruited following review by the DSMB. The lowest dose was based on a prior human study in which 50 million NSCs were injected and were found to be safe.14 The dose at which no more than one of the six patients had a dose-limiting toxic effect was defined as the recommended phase 2 dose. After the injections were completed, the remainder of the surgery consisted of routine wound closure. Standard radiotherapy and chemotherapy began 10–14 days after surgery and NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. All patients were maintained on low dose steroids throughout the treatment regimen; however, the dose was tapered down whenever possible (Figure S1, appendix p. 21). Long-term follow-up of general health status and any side effects continued for life. Patients were able to withdraw from the study at any time. Patients could also be taken off the study treatment and/or study as a whole at the discretion of the investigator for safety, behavioral, or administrative reasons.

Disease assessment was done through medical history, MRI, blood counts, and chemistry values at screening and follow-ups. MRI scan assessments were done at screening and then after surgery/product injection at days 2, 28, 56, and every eight weeks thereafter. Clinical laboratory monitoring was done at screening, day 0 (day of surgery/product injection), and afterwards. Hematology and serum chemistry panels were checked at screening and days 0, 2, 3, 7, 14, 28, 28, 42, 56, and every eight weeks thereafter. Coagulation panels were assessed at screening and days 0, 3, 7, and 14. Blood sampling for cytokine profiling and immune studies was done at days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28; additional sampling at day 56 and after day 200 were collected for immune explorations. Urine analysis and microscopy was done at screening and at days 0 and 14. Urine or serum pregnancy test was done at screening and at day 0 (appendix p.38).

Adverse events were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03), and the relatedness to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 was assessed. Dose-limiting toxicity was defined as any NSCCRAd-S-pk7–related, non-hematologic adverse event ≥ grade 3 occurring from surgery until end of chemo-radiotherapy. Adverse events were reported in a routine manner at scheduled times during the trial at screening and at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 28, and 56. The DSMB reviewed any complications arising from the therapy prior to the enrollment of new patients. All patients experiencing an adverse event, regardless of its relationship to study drug, were followed until: the adverse event resolved or the symptoms or signs that constituted the adverse event returned to baseline; any abnormal laboratory values returned to baseline; there was a satisfactory explanation other than the study drug for the changes observed; or death.

Objective tumor response to therapy was determined by the iRANO criteria.17 Progression-free survival constituted the time from surgery/product injection to first confirmed disease progression as determined by the objective tumor response. Survival time was calculated from the time of surgery/product injection to death. Quality of life was evaluated using the summary score on a patient self-report measure, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Brain component (FACT-Br v4).18

Blood collection for immune research studies, such as lymphocytic infiltration studies and serum cytokine profiling, was done before surgery/product injection, on the day of surgery/product injection, after surgery/product injection, and post-radiotherapy. Details on blood processing, flow cytometry, viral titrations, serum biomarker analysis, and enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) analysis are presented in the Supplementary Methods (appendix p. 3–4).

Post-treatment surgical specimens were immunostained for adenovirus proteins and for tumor-specific proteins. Autopsy examination of the brains of four consented patients allowed histopathological assessment of the tumor microenvironment. Samples were collected from various regions throughout the brain for evaluation (Table S1, appendix p. 7). A nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the v-myc DNA in brain specimens was done to check for the presence of NSCs post autopsy. Multiplex staining was done for detection of immune cells before and after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. Further details are presented in Supplementary Methods (appendix p. 4–6).

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was to determine the safety and toxicity profile and the maximum tolerated dose for a future phase 2 trial with NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 in patients with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas. The secondary endpoints were to determine the tumor response, estimate progression-free survival and overall survival, and evaluate the quality of life of patients while on treatment. Exploratory endpoints were to evaluate cytokine profiles and blood immune responses and to determine whether survival rates correlated with the extent of the immune response.

Statistical Analysis

This study aimed to find the maximal tolerated dose of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 using the 3+3 trial design. The final sample size would depend on the real-time response of patients for each dose, while the maximum sample size is usually six times the number of doses. Three dose levels were evaluated. Patients on dose level 1 (n=3) received 5.00 × 107 NSCs loading 6.25 × 1010 viral particles (vp). Patients on dose level 2 (n=3) were treated with 1.00 × 108 NSCs loading 1.25 × 1011 vp. Cohort 3 (n=6) received the third dose level at 1.50 × 108 NSCs loading 1.875 × 1011 vp. No further dose escalation was planned. All analyses were conducted in the safety population (n=12), which is defined as all patients who received at least one dose of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7. Adverse events were summarized by term and grade. Subjects who experienced the same event on more than one occasion were counted once in the event frequency. Objective tumor response was assessed by the iRANO criteria. Response rates and two-sided Clopper-Pearson 95% confidence intervals were estimated. To visualize the total evaluable population and describe differences between different treatment groups, Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted for both progression-free survival and overall survival. Post-hoc subgroup analysis was done to analyze the levels of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes in the blood samples of patients between days 3 and 14 using the student’s paired t test. GraphPad Prism Version 8 for Windows (GraphPad Software, www.graphpad.com) and the R statistical environment [R] version 4.0.2 were used to conduct the statistical analyses along with extension packages survival (v 3.2–3),19 survminer (v 0.4.8),20 and GenBinomApps (v 1.1).21 The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03072134.

Role of the Funding Source

The study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (P50 CA221747, R35CA197725). The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had access to the data reported. The corresponding author (MSL) had full access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Between April 24, 2017 and November 13, 2019, a total of 13 patients were screened. Twelve patients were enrolled and treated with NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 according to the assigned dose level (n=12) (Figure S2, appendix p. 22). One patient was excluded as their tumor invaded the ventricular system. At the time of analysis on March 3, 2021, median follow-up was 18 months (IQR 14–22). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics in evaluable population.

| Total Evaluable (N=12) | Cohort 1 (N=3) | Cohort 2 (N=3) | Cohort 3 (N=6) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | Mean (SD) | 54 (14) | 58 (10) | 55 (10) | 52 (18) |

| Median (IQR) | 52 (48–65) | 63 (55–64) | 50 (49–58) | 52 (47–65) | |

| Sex (%) | Female | 7 (58%) | 2 (67%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (50%) |

| Male | 5 (42%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (33%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | Non-Hispanic | 12 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 6 (100%) |

| Race (%) | Asian | 1 (8%) | - | 1 (33%) | - |

| Black | 1 (8%) | - | - | 1 (17%) | |

| White | 10 (83%) | 3 (100%) | 2 (67%) | 5 (83%) | |

| Karnofsky Score | 70 | 1 (8%) | 1 (33%) | - | - |

| 80 | 1 (8%) | - | 1 (33%) | - | |

| 90 | 7 (58%) | 2 (67%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (50%) | |

| 100 | 3 (25%) | - | - | 3 (50%) | |

| Glioma Subtype (%) | Glioblastoma (WHO Grade IV) | 11 (92%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 5 (83%) |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO Grade III) | 1 (8%) | - | - | 1 (17%) | |

| MGMT (%) | Methylated | 3 (25%) | 1 (33%) | - | 2 (33%) |

| Unmethylated | 9 (75%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (100%) | 4 (67%) | |

| IDH1/2 (%) | Mutant | 2 (17%) | - | - | 2 (33%) |

| Wild | 10 (83%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 4 (67%) | |

| Follow-up (Months)* | Median (IQR) | 18 (14–22) | 24 (21–30) | 16 (14–18) | 16 (12–21) |

| Number of Surgeries (%) | 1 | 6 (50%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (50%) |

| 2 | 6 (50%) | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) | 3 (50%) |

Follow-up time is calculated from day of surgery/NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection.

Histopathological evaluation identified 11 (92%) of 12 patients with glioblastoma and one (8%) of 12 patients with anaplastic astrocytoma. Two (17%) of 12 tumors harbored an IDH1 mutation. MGMT gene promoter was methylated in three (25%) of 12 patients, including the two IDH-mutated tumors.

One (17%) of six patients taking the third dose level developed a grade 2 subdural fluid collection 22 days after surgery/product injection that was deemed possibly related to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 administration. Another patient (17%) of the six taking the third dose level developed meningitis (grade 3) due to the inadvertent injection of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 into the ventricle. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) trickled into the open ventricle. Collection and subsequent analysis of CSF was consistent with viral meningitis. After hospitalization, the patient fully recovered. Subsequently three additional patients were enrolled at the same dose level without major toxicity and complications. This was the highest pre-specified dose level; a formal dose limiting toxicity was not observed, and a dose of 1.50 × 108 NSCs loading 1.875 × 1011 vp is the recommended phase 2 dose for further exploration. Details on trial dosage are provided in Table S2 (appendix p. 8).

Treatment emergent adverse events are summarized in Table 2. None of these events appeared to be related to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 and all are commonly observed toxicities due to subsequent chemo- and radiotherapy. A full record of reported adverse events is presented in Table S3 (appendix p. 9). Five severe adverse events were reported, including a thromboembolic event, encephalopathy, cerebral edema, muscle weakness, and meningitis. Only viral meningitis was probably related to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 (Table S4, appendix p. 14). All patients recovered fully from their adverse events, and there were no subject dropouts or deaths due to an adverse event.

Table 2:

Adverse events in evaluable patients (N=12).

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Incidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSC-CRAd-S-pk7-Related | ||||

| Meningitis † | - | - | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) |

| Subdural fluid collection ‡ | - | 1 (8%) | - | 1 (8%) |

| All Adverse Events* | ||||

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 3 (25%) | 3 (25%) | 5 (42%) | 11 (92%) |

| Headache | 4 (33%) | 5 (42%) | 1 (8%) | 10 (83%) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 7 (58%) | 3 (25%) | - | 10 (83%) |

| Anemia | 7 (58%) | 2 (17%) | - | 9 (75%) |

| Fatigue | 7 (58%) | 2 (17%) | - | 9 (75%) |

| Nausea | 8 (67%) | - | - | 8 (67%) |

| Hypertension | 1 (8%) | 2 (17%) | 5 (42%) | 8 (67%) |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 (8%) | 5 (42%) | 1 (8%) | 7 (58%) |

| Hyponatremia | 4 (33%) | - | 3 (25%) | 7 (58%) |

| Alopecia | 5 (42%) | 2 (17%) | - | 7 (58%) |

| Constipation | 4 (33%) | 2 (17%) | - | 6 (50%) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 6 (50%) | - | - | 6 (50%) |

| Platelet count decreased | 5 (42%) | 1 (8%) | - | 6 (50%) |

| Sinus bradycardia | 5 (42%) | - | - | 5 (42%) |

| Sinus tachycardia | 5 (42%) | - | - | 5 (42%) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 5 (42%) | - | - | 5 (42%) |

| Muscle weakness | - | 1 (8%) | 4 (33%) | 5 (42%) |

| Vomiting | 4 (33%) | - | - | 4 (33%) |

| Fever | 3 (25%) | 1 (8%) | - | 4 (33%) |

| Thromboembolic event | 1 (8%) | 2 (17%) | 1 (8%) | 4 (33%) |

| Hypocalcemia | 3 (25%) | - | - | 3 (25%) |

| Hypophosphatemia | - | 3 (25%) | - | 3 (25%) |

| Insomnia | 1 (8%) | 2 (17%) | - | 3 (25%) |

| Rash maculo-papular | 3 (25%) | - | - | 3 (25%) |

| Hypotension | 3 (25%) | - | - | 3 (25%) |

Adverse events occurring in >2 patients are presented.

Probably related

Possibly related

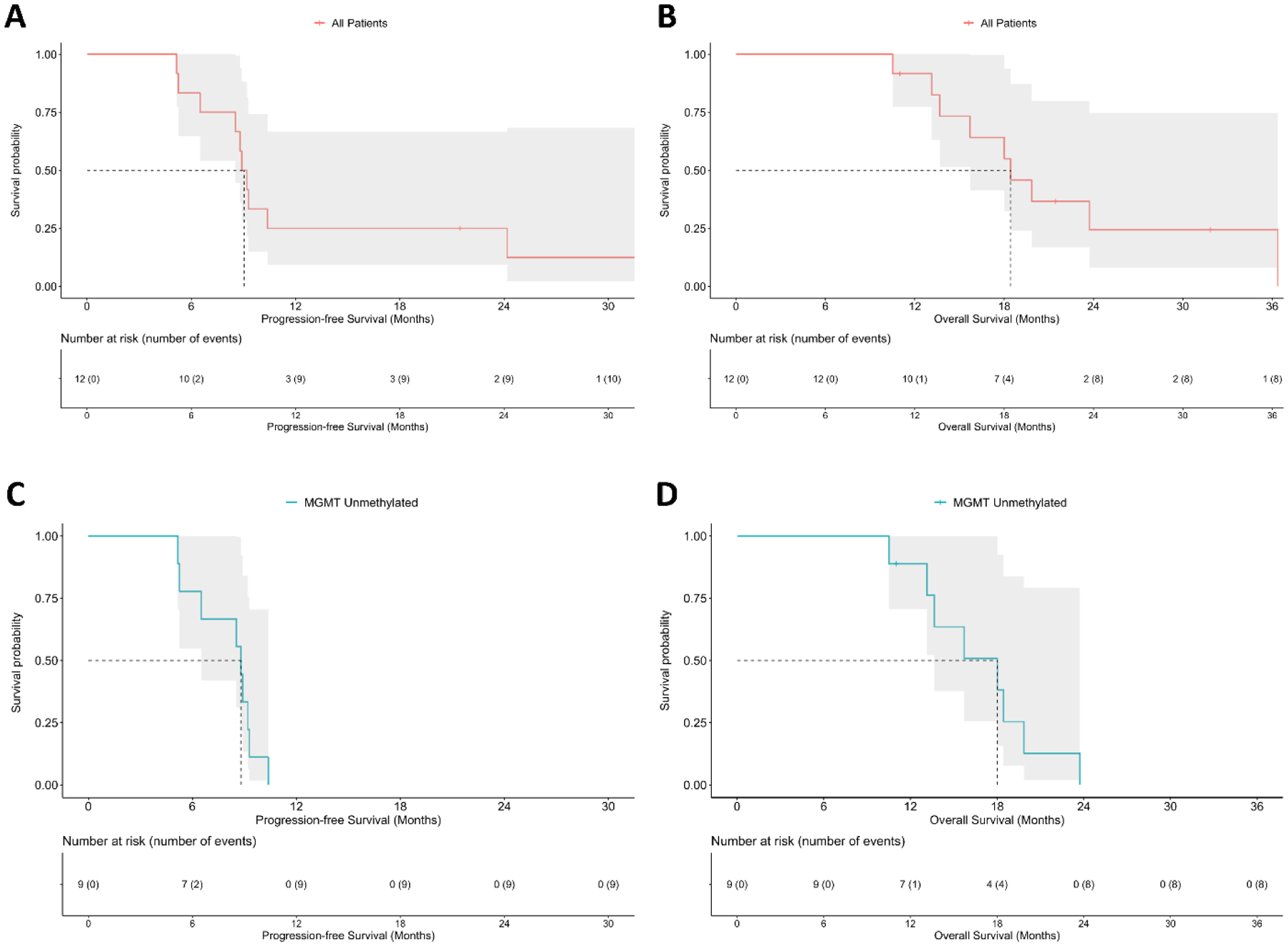

After resection, residual evaluable tumor was present in nine (75%) of 12 patients. Assessment of best response showed that one (8%) of 12 patients had a partial response, one (8%) of 12 patients exhibited pseudo-progression, and ten (83%) of 12 patients had stable disease (Table S5, appendix p. 15). At database lock, ten (83%) of 12 patients had progressed, and nine (75%) of 12 patients had died. The median progression-free survival was 9.05 months (95% CI 8.54, NA) (Figure 1A). The median overall survival was 18.4 months (95% CI 15.7, NA) (Figure 1B). Survival probabilities at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months are presented in Tables S6 and S7 (appendix p. 16,17). Differences in progression-free survival and overall survival between the cohorts are presented in Figures S3–S8 (appendix p. 23–28). In the subset of patients with glioma containing an unmethylated MGMT promoter, median progression-free survival was 8.8 months (95% CI 6.51, NA) (Figure 1C), and median overall survival reached 18.0 months (95% CI 13.67, NA) (Figure 1D). For the three (25%) of 12 patients with MGMT methylated tumors, one uncensored patient had a progression-free survival and overall survival of 24.2 months and 36.4 months, respectively; two patients were censored at last follow-up time (Figure S7–S8, appendix p. 27–28).

FIGURE 1: Survival outcomes in patients who received NSC-CRAd-S-pk7.

The median progression-free survival in all evaluable patients (n=12) is 9.05 months (95% CI 8.54, NA) (A). The median overall survival in all evaluable patients is 18.4 months (95% CI 15.7, NA) (B). In the subset of patients with high grade gliomas containing an unmethylated MGMT promoter (n=9), the median progression-free survival was 8.8 months (95% CI 6.51, NA) (C), and median overall survival was 18.0 months (95% CI 13.67, NA) (D).

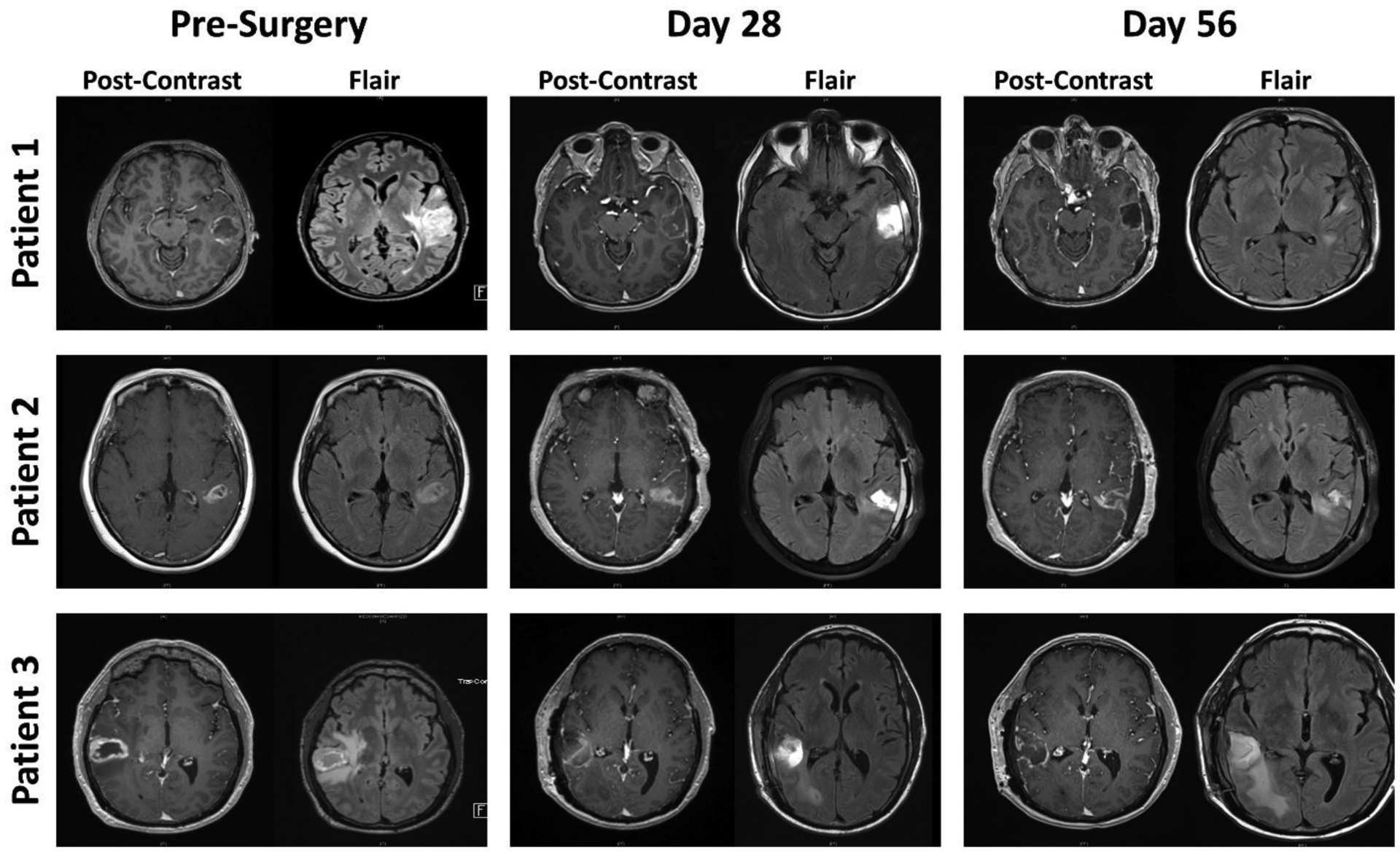

MRI – before and after the treatment regimen – showed a decrease in contrast enhancement and peritumoral hyperintensity around the resection cavity after therapy (Figure 2). Patients had a decline in quality of life reported until the cessation of radiotherapy, where they subsequently rebounded back to near baseline levels (Figure S9, appendix p. 29).

FIGURE 2: Summary of radiological responses of three patients with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans before neurosurgical procedure and at days 28 and 56 after surgery and NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. Contrast enhancement and peritumoral hyperintensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images decreased around the resection cavity with time. Patient 1 partially responded to treatment, whereas patients 2 and 3 had stable disease.

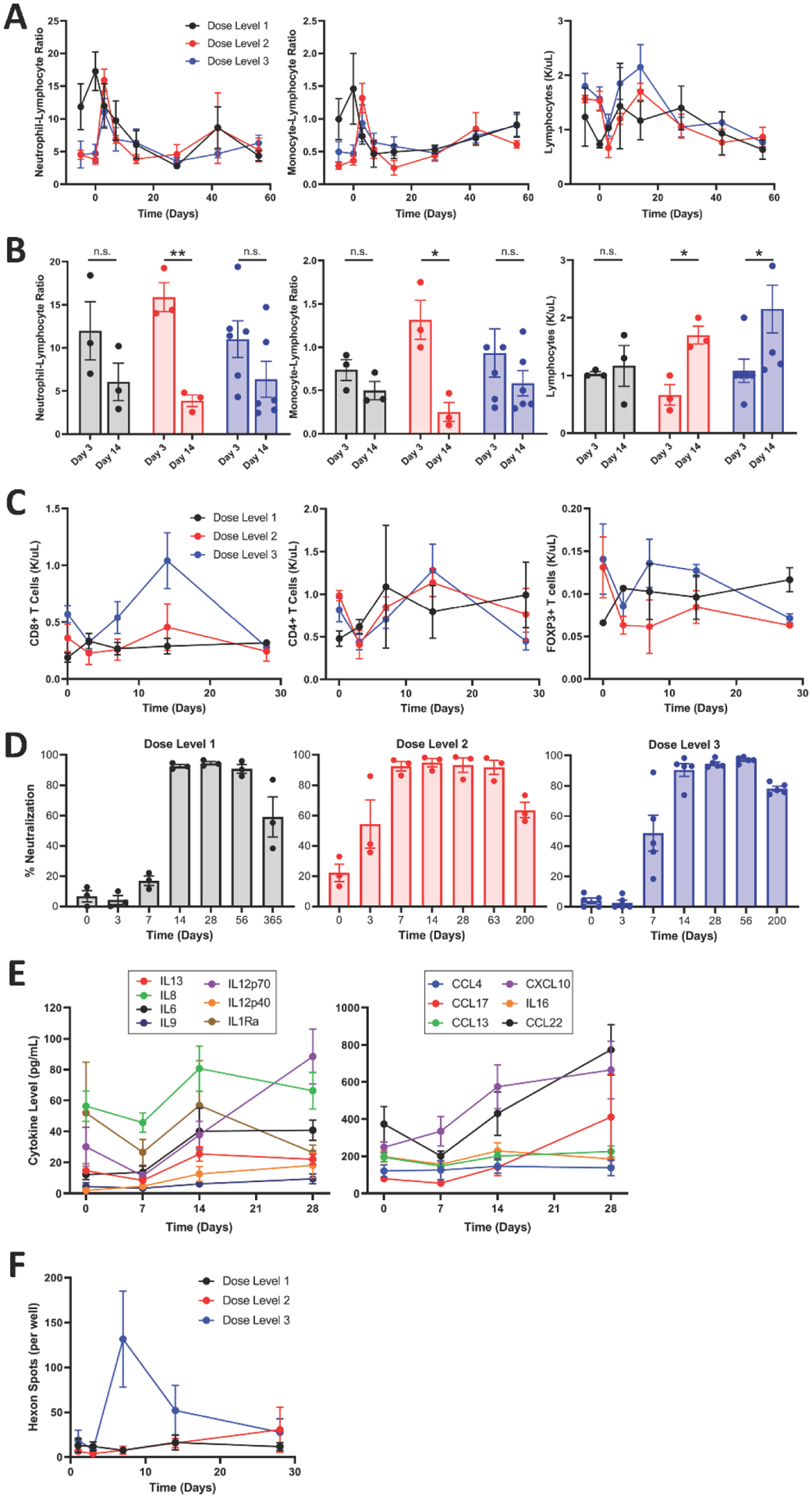

Exploratory studies allowed the assessment of the immune response to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7. Flow cytometric analysis revealed an early increase in neutrophil and monocyte ratios (Figure 3A), followed by an increase in CD8+ T cells 14 days after surgery/product injection; especially in cohorts receiving higher doses of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 (Figure 3B and C). The expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines– granzyme B, IFN-γ, and TNF-α–regardless of tumor tissue depth suggests cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells in the overall tumor tissue (Figure S10, appendix p. 30). Anti-Ad5 neutralizing antibodies were detected in low titers 14 days after treatment at the first dose level and within a week at higher dose levels (Figure 3D; Figures S11–S13, appendix p. 31–33). Circulating cytokine profiles in patients’ serum are presented in Figure 3E. ELISpot assay revealed anti-viral immunity through the detection of hexon spots, which increased as the dose of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 increased (Figure 3F); difference between dose levels could be markedly visualized on days 7 and 14 after surgery/NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection (Figure S14, appendix p. 34). One year later, anti-tumoral immunity could be detected in one (8%) of 12 patients that received NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 (Figure S15, appendix p. 35).

FIGURE 3: Immune activity in response to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7.

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and total lymphocyte count were compared at different time points before surgery/product injection and throughout the treatment course. NLR and MLR spiked 3 days after surgery/product injection in all three dose levels. This peak diminished by day 14, when the number of lymphocytes increased (A). A focused comparison between days 3 and 14 post surgery/product injection showed a significant decrease in NLR (p=0.0027) and MLR (p=0.013) at dose level 2 and significant increase in absolute lymphocyte count in both dose levels 2 (p=0.011) and 3 (p=0.043) (B). Integration of lymphocyte counts into the flow cytometric analysis showed that CD8+ T cells increased in patients who were receiving the third dose level 14 days after surgery/NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection (C). Anti-Ad5 neutralizing antibodies were detected in low titers (1:20 dilution of plasma) 14 days after surgery and NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 treatment at the first dose level and within a week at higher dose levels (D). Analysis of circulating cytokine profiles in patients’ serum showed an initial drop in levels of IL8, IL1Ra, IL12p70, IL13, and CCL22 7 days after surgery/product injection. This was followed by an increase in levels up until day 14 for IL8, IL1Ra, IL6, IL13, and IL16; after which the levels of these cytokines plateaued or diminished. Other cytokines, such as IL12p70, CXCL10, CCL17, and CCL22, continued to increase into day 28 (E). Anti-viral and anti-tumoral immunities were evaluated through an ELISpot assay. Anti-viral immunity was determined through the detection of hexon spots, which increased as the dose of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 increased (F). Dose level 1 (n=3), Dose level 2 (n=3), Dose level 3 (n=6). For complete blood count analysis, Dose level 3 (n=5). Student’s paired t-test was used for (C), p<0.05*, p<0.01**.

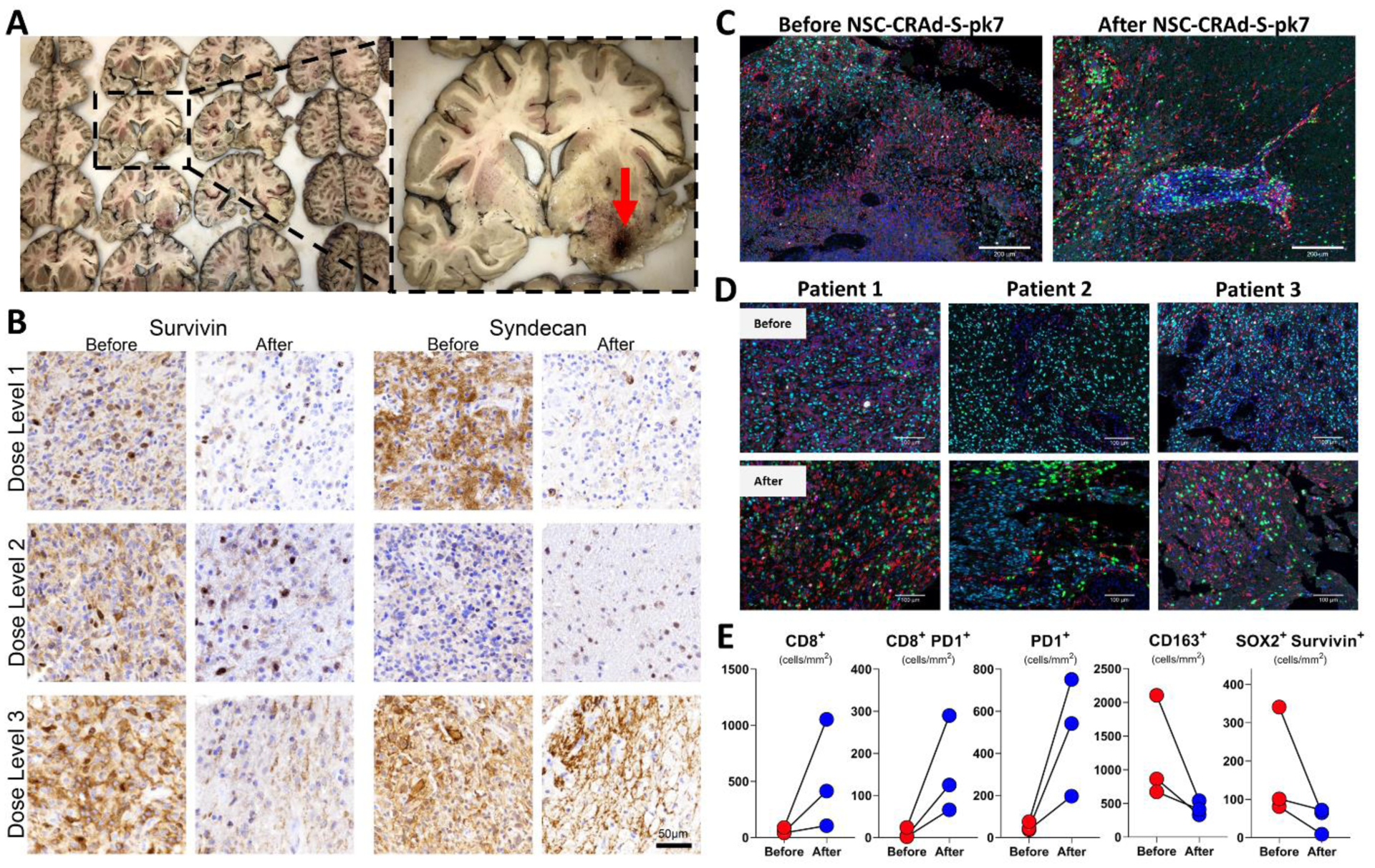

Viral traces of E1A and hexon, as well as v-myc DNA, which is used to immortalize the NSCs, could not be detected in the sampled brains (Figure 4A; Figure S16, appendix p. 36). In eight (67%) of 12 patients who underwent repeat surgical resections or autopsy, we sampled and compared tumor tissues before and after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 administration. As the survivin promoter is incorporated within the virus and syndecan is targeted by the viral capsid, tumor-specific marker staining of survivin and syndecan-1 showed a decrease in expression after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 treatment (Figure 4B). Immunohistochemical staining results of all collected samples are presented in Table S8 (appendix p. 18). Multiplex staining showed an increase in CD8+ T cells, specifically at the tumoral site, after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection (Figure 4C). These findings were seen across samples from three (100%) of three different patients whose tissues were selected for analysis, as more CD8+ T cells were seen at the recurred glioma lesion post NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection (Figure 4D). Quantitative analysis of staining results showed increased numbers of CD8+ T cells and higher expression of PD-1 after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. Levels of CD63+ cells and SOX2+ cells that express survivin decreased after treatment (Figure 4E).

FIGURE 4: Histopathological analysis of tumor samples before and after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7.

Samples for immunohistochemistry were collected from various regions throughout the brain for histopathological evaluation; sampled regions from the brain in the panel are detailed in Table S1, appendix p. 7. Immunohistochemical staining of collected autopsy samples did not detect E1A or hexon at the site of injection (red arrow) or in other tested samples from the resection cavity. In addition, v-myc immortalized in the injected human NSCs could not be detected via nested PCR amplification (A). Tumor samples from patients that underwent two surgical resections were collected before and after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. Tumor-specific marker staining of survivin and syndecan-1 showed a decrease in expression after treatment (B). Multiplex staining showed an increase in CD8+ T cells after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection, with more cells traveling from the blood vessels to the tumoral region and sparing the peri-tumoral areas (C). These findings were seen across samples from three different patients, as more CD8+ T cells were seen in the tumor zone post injection (D). Quantitative analysis of staining results revealed an increase in CD8+ T cells and PD-1 expression and decreased numbers of CD163+ cells and SOX2+ cells that express survivin after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection (E). Color key for (D) and (E): Green-CD8+, Red-CD163+, Cyan-SOX2+, Magenta-PD-1+, White-Survivin, Blue-DAPI.

DISCUSSION

The phase 1 trial showed that NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 was safe in patients with high-grade malignant gliomas. Treatment with NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 during initial surgery immediately followed by standard chemo-radiotherapy is feasible and did not lead to undue delay or complications. Tumor response and survival outcomes demonstrated favorability of the treatment regimen without jeopardizing the quality of life of patients. Exploratory studies described correlative evidence of the immune-mediated anti-glioma and anti-viral responses to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first-in-human trial to test the neural stem cell delivery of an engineered oncolytic adenovirus. In addition, this clinical work is unique among neuro-oncology and virotherapy trials as it involves patients with ‘newly diagnosed’ gliomas, rather than recurrent disease.

The primary endpoint of the trial was met as the addition of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 to resection and the standard of care was shown to be safe and non-toxic. No dose-limiting toxicity was noted, and the highest pre-assigned dose was the maximal tolerated dose. Only one severe adverse event, viral meningitis (grade 3), in one (8%) of 12 patients was deemed to be probably related to the treatment. This was due to the unintended injection of the regimen into the cerebral ventricle. Still, the patient was adequately managed and recovered fully in the following days. Oncolytic adenoviruses7,8 and humanized NSCs14 have been shown to be safe and nontoxic in previous clinical studies.

NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 was injected multiple times in different sites in the wall of the resection cavity. Preclinical studies support the notion that intracerebral injections of NSCs can achieve greater tumor coverage than intravenous administration.22 Clinical studies using oncolytic adenoviruses had shown that a single injection into the tumor at the time of craniotomy achieves local delivery of the virus at the site of needle injection.23 We believed that multiple injections of NSCs in the tumor bed may increase lateral spread of the virus given the propensity of NSCs to disseminate throughout the tumor mass. MRI visualization of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 had shown its effective tumor coverage potential when injected in murine glioma models.24

Early initiation of chemo-radiotherapy following surgery and NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection was achievable and free of complications. Preclinical studies had shown that radiation enhances replication of CRAd-Spk7 in virus-infected glioma cells up to a 100-fold, when compared to CRAd-S-pk7 treatment alone.16 This synergistic effect was also seen upon combining CRAd-S-pk7 with temozolomide. The oncolytic virus and the alkylating agent eradicated malignant glioma cells via autophagic and apoptotic cell death mechanisms.25 Further studies showed that NSCs carrying CRAd-S-pk7 retained their tumor-tropic properties in the presence of ionizing radiation and temozolomide, and that the delivery of NSC-CRAd-Spk7 prior to rather than after radiotherapy and temozolomide treatment increased median survival of mice bearing patient-derived glioma xenografts by 30%.26

Trial results demonstrated correlative anti-tumor activity of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7. Evaluation of best response showed that one (8%) of 12 patients had a partial response to treatment and ten (83%) of 12 patients had stable disease. Other oncolytic adenoviruses have shown variable responses against recurrent malignant gliomas. An E1B-attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, did not show definite anti-tumor efficacy, as 23 (96%) of 24 patients experienced progression of recurrent disease.7 Yet, two (8%) of 24 patients that had anaplastic astrocytoma remained alive and tumor free more than 17 years after undergoing ONYX-015 treatment.27 The E1A-edited adenovirus, DNX-2401, demonstrated tumor reductions in 18 (72%) of 25 patients with recurrent gliomas, with five (20%) of 25 patients surviving more than 3 years.8 While both ONYX-015 and DNX-2401 trials reported rapid increase in gadolinium after treatment administration that was suggestive of inflammatory pseudo-progression, we did not observe a similar trend with NSC-CRAd-S-pk7. Comparison between the clinical outcomes of virotherapy trials in patients with malignant gliomas is presented in Table S9 (appendix p. 19).

The addition of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 to neurosurgery and chemo-radiotherapy showed favorable survival outcomes in comparison to historical controls. Patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma that are treated with radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide have a progression-free survival and overall survival of 6.9 and 14.6 months, respectively.1 In our study, the median progression-free survival and overall survival with NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 reached 9.05 and 18.4 months, respectively. Furthermore, NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 showed encouraging survival outcomes in the subpopulation of patients whose tumors possessed an unmethylated MGMT promoter. Those patients are known to not benefit from temozolomide treatment and exhibit poor prognostic outcomes.28 The median progression-free survival and overall survival in this subset of patients are 5.3 and 12.7 months, respectively.28 Interestingly, NSCCRAd-S-pk7-based therapy exhibited median progression-free survival and overall survival of 8.8 and 18.0 months, respectively. Comparison between the clinical outcomes of trials in patients with newlydiagnosed malignant gliomas is presented in Table S10 (appendix p. 20).

NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 did not adversely affect the quality of life of the patients in the trial, as measured by the self-report tool, FACT-Br (v4). The quality of life data paralleled that of the standard treatment in gliomas.29 Oncolytic virotherapy has generally proven to barely affect quality of life in patients with other cancers.30 In glioblastoma, a case report of a patient that received oncolytic virotherapy reported normal quality of life for 6 years after treatment.31

Immune studies strongly suggest that NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 influences the host immunity in patients with high-grade gliomas. The trial design allowed the assessment of immune-mediated responses that correlate with NSC-CRAd-S-pk7, specifically, as temozolomide and radiation therapies were started two weeks after surgery and NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. Early immune responses showed an increase in inflammatory myeloid recruitment followed by an increase in circulating levels of lymphocytes, especially CD8+ T cells, two weeks later. The CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment were shown to be active immune cells, due to the increase in CD8+/CD4+ ratios,32 and the expression of the early activation marker CD69, which indicates recent activation and tissue infiltration.33 This inflammatory scheme conforms to the typified models of immune reactivity in humans and to other oncolytic adenovirus responses.8 Importantly, these changes were not observed in the cohort that received the lowest dose of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7, which may suggest that higher doses promote systemic immunity and might reflect better anti-tumoral immune responses. Moreover, the cytokine profile described in response to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 can further help in following up the immune-mediated response to therapy.

Histopathological studies in patients who underwent repeat surgical resection at the time of tumor progression had a decreased expression of survivin and syndecan-1 after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 treatment. Higher survivin expression in patients with glioma has been associated with resistance to temozolomide therapy and worse overall survival.34,35 Furthermore, syndecan-1 expression in human glioma is correlated with advanced tumor progression and poor prognosis.36 As such, the decrease in survivin and syndecan-1 expression following NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 therapy may be due to the replication of CRAd-S-pk7 in the glioma cells, which leads to their death.

We did not detect NSCs or viral components from the different regions of the sampled brains 4–24 months after NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection. This indicates that the regimen was effectively cleared, which further highlights the safety of the approach. NSCs have been shown to be cleared within 30 days from day of administration,11 whereas CRAd-S-pk7 DNA can be detected in brains for up to 62 days after injection.37 As such, multiple administrations of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 are potentially safe and may achieve greater benefit in a future higher phase trial.

Multiplex staining analysis of tumors collected during the second surgical resection or at autopsy showed increasing numbers of CD8+ T cells at the tumor site. We believe that this is induced by the NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection, as immunophenotyping of newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastomas did not show changes in the number of CD8+ T cells.38,39 So far, immunotherapeutic treatment strategies have been limited by T cell restriction in high grade gliomas.38 In this context, NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 led to an increase in PD-1 expression. As such, combining NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy can be a promising approach in a future trial.

Limitations of the study include the fact that it is a single-arm, open-label study with no comparator group. Statistical evaluation of a phase 1 trial has limitations in terms of patient expectations regarding efficacy. The favorability in survival outcomes can be due to early initiation of radiation therapy and temozolomide, more intensive care of the patients on the trial, and/or institution-specific performance. One (8%) of 12 patients, with a right parieto-temporal tumor, underwent a temporal lobectomy, which is reported to improve survival outcomes.40 The validation of the survival outcomes, as well as the immune and histopathological findings, will require a phase 2/3 study with a larger cohort and a cell-labeling component to prove points of interest.

In conclusion, this trial has shown the relative safety and tolerability of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 injection during surgery in patients with newly diagnosed malignant gliomas. Immediate initiation of standard chemo-radiotherapy in this trial was feasible and did not lead to undue delay or complications. The treatment portends favorable clinical outcomes, especially in patients with MGMT unmethylated gliomas. This trial sets the stage for a phase 2 study, where the efficacy of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 in prolonging survival in a larger cohort of patients with controlled conditions can be explored. As no formal dose limiting toxicity was observed, the highest dose of 1.50 × 108 NSCs loading 1.875 × 1011 vp is the recommended phase 2 dose for further exploration. Multiple injections of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 and/or its combination with immune-modulatory therapies and/or checkpoint inhibitors can further increase the clinical benefit achieved.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

On January 23, 2021, we searched PubMed, without any language or date restrictions, using terms related to glioma, glioblastoma, neural stem cells (NSCs), and oncolytic virus. We found no trials that used NSCs for the delivery of an oncolytic adenovirus in patients with glioma. Previous research has shown the ability of oncolytic viruses to be safe and active in patients with recurrent gliomas; however, their tumor targeting properties were limited by decreased dissemination and infiltration in tumor tissue. NSCs have been shown to effectively migrate and disseminate in the brain to target glioma cells. This provided the rationale for using NSCs to deliver an engineered oncolytic adenovirus in patients with high-grade malignant glioma.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first-in-human trial to test the neural stem cell delivery of an engineered oncolytic adenovirus. In addition, this clinical work is distinctive among neuro-oncology and virotherapy trials as it explores patients with ‘newly diagnosed’ gliomas, rather than recurrent disease. The phase 1 trial showed that NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 was safe and tolerable in patients with high-grade malignant gliomas and immediate start of standard chemo-radiotherapy was feasible without undue delay or complications. In addition, NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 demonstrated promising antitumor activity; especially in patients with O6-methylguanine–DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) unmethylated gliomas.

Implications of all the available evidence

The safety, efficacy, and durable benefit achieved by the addition of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 to surgical resection and chemo-radiotherapy is particularly noteworthy in the setting of an aggressive disease, such as newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas. This trial provides the foundation for a higher phase, controlled trial, where survival outcomes in response to NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 can be evaluated in a larger cohort of patients. Multiple injections of NSC-CRAd-S-pk7 through an intracranial catheter and/or its combination with checkpoint inhibitors, and/or other immune modulatory therapies may potentially increase clinical benefit.

Acknowledgments

This work has been fully supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. MSL reports grants from the National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study. We thank Aida Rashidi, Kathleen McCortney, Yu Han, Aurora Lopez-Rosas, and Cheol Hong Park for their technical support. The authors are indebted to the patients and their relatives for partaking in this trial.

Declaration of interests

MSL, KSA and DTC have an issued patent “Tropic cell based virotherapy for the treatment of cancer” (US Patent Nos. 10,238,699, 10,709,745 Issued 3/26/19) that is related to the study. MSL reports grants from the National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study. KSA was the CSO and Director of TheraBiologics (company in process of being dissolved); she neither has assets nor receives financial benefit from the company. JP reports grants from The Ivy Foundation, during the conduct of the study. CDH reports salary payments from Southern Research, outside the work in this study. RVL reports honoraria from Novocure for advisory roles, EBSCO Publishing and Medlink Neurology for medical editing, ECRI for reviewing medical content, and the American Physician Institute for creating and presenting board review CME material, outside the work in this study. RS reports non-financial support from CarThera, and personal fees from Celularity, CranioVation, TriAct, Hemispherian, Northwest Biotherapeutics, GT Medical Technologies, Insightec, and ZaiLab, outside the work in this study. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data sharing

The trial protocol is provided in the appendix and will be available online for an indefinite period.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(10): 987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2017; 318(23): 2306–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholas MK, Lukas RV, Chmura S, Yamini B, Lesniak M, Pytel P. Molecular heterogeneity in glioblastoma: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Semin Oncol 2011; 38(2): 243–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and Bevacizumab in Progressive Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(20): 1954–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wann A, Tully PA, Barnes EH, et al. Outcomes after second surgery for recurrent glioblastoma: a retrospective case-control study. J Neurooncol 2018; 137(2): 409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso MM, Jiang H, Gomez-Manzano C, Fueyo J. Targeting brain tumor stem cells with oncolytic adenoviruses. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 797: 111–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiocca EA, Abbed KM, Tatter S, et al. A phase I open-label, dose-escalation, multi-institutional trial of injection with an E1B-Attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, into the peritumoral region of recurrent malignant gliomas, in the adjuvant setting. Mol Ther 2004; 10(5): 958–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang FF, Conrad C, Gomez-Manzano C, et al. Phase I Study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) Oncolytic Adenovirus: Replication and Immunotherapeutic Effects in Recurrent Malignant Glioma. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(14): 1419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conti L, Cattaneo E. Neural stem cell systems: physiological players or in vitro entities? Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11(3): 176–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, et al. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: evidence from intracranial gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97(23): 12846–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Metz MZ, et al. Neural stem cell-mediated enzyme/prodrug therapy for glioma: preclinical studies. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5(184): 184ra59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulasov IV, Zhu ZB, Tyler MA, et al. Survivin-driven and fiber-modified oncolytic adenovirus exhibits potent antitumor activity in established intracranial glioma. Hum Gene Ther 2007; 18(7): 589–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JW, Auffinger B, Spencer DA, et al. Single dose GLP toxicity and biodistribution study of a conditionally replicative adenovirus vector, CRAd-S-pk7, administered by intracerebral injection to Syrian hamsters. J Transl Med 2016; 14(1): 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portnow J, Synold TW, Badie B, et al. Neural Stem Cell-Based Anticancer Gene Therapy: A Firstin-Human Study in Recurrent High-Grade Glioma Patients. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(12): 2951–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed AU, Thaci B, Tobias AL, et al. A preclinical evaluation of neural stem cell-based cell carrier for targeted antiglioma oncolytic virotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105(13): 968–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nandi S, Ulasov IV, Tyler MA, et al. Low-dose radiation enhances survivin-mediated virotherapy against malignant glioma stem cells. Cancer Res 2008; 68(14): 5778–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada H, Weller M, Huang R, et al. Immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology: a report of the RANO working group. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(15): e534–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weitzner MA, Meyers CA, Gelke CK, Byrne KS, Cella DF, Levin VA. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale. Development of a brain subscale and revalidation of the general version (FACT-G) in patients with primary brain tumors. Cancer 1995; 75(5): 1151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therneau T, Grambsch P. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. 1 ed. New York: Springer-Verlag New York; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kassambara A, Kosinski M, Biecek P. survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using ‘ggplot2’. 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer.

- 21.Lewitschnig H, Lenzi D. GenBinomApps: Clopper-Pearson Confidence Interval and Generalized Binomial Distribution. 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=GenBinomApps.

- 22.Barish ME, Herrmann K, Tang Y, et al. Human Neural Stem Cell Biodistribution and Predicted Tumor Coverage by a Diffusible Therapeutic in a Mouse Glioma Model. Stem Cells Transl Med 2017; 6(6): 1522–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang FF, Bruner JM, Fuller GN, et al. Phase I trial of adenovirus-mediated p53 gene therapy for recurrent glioma: biological and clinical results. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21(13): 2508–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morshed RA, Gutova M, Juliano J, et al. Analysis of glioblastoma tumor coverage by oncolytic virus-loaded neural stem cells using MRI-based tracking and histological reconstruction. Cancer Gene Ther 2015; 22(1): 55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulasov IV, Sonabend AM, Nandi S, Khramtsov A, Han Y, Lesniak MS. Combination of adenoviral virotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy eradicates malignant glioma through autophagic and apoptotic cell death in vivo. Br J Cancer 2009; 100(7): 1154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobias AL, Thaci B, Auffinger B, et al. The timing of neural stem cell-based virotherapy is critical for optimal therapeutic efficacy when applied with radiation and chemotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. Stem cells translational medicine 2013; 2(9): 655–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiocca EA, Nassiri F, Wang J, Peruzzi P, Zadeh G. Viral and other therapies for recurrent glioblastoma: is a 24-month durable response unusual? Neuro Oncol 2019; 21(1): 14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegi ME, Diserens A-C, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. The New England journal of medicine 2005; 352(10): 997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lieberman NAP, Vitanza NA, Crane CA. Immunotherapy for brain tumors: understanding early successes and limitations. Expert Rev Neurother 2018; 18(3): 251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(25): 2780–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gesundheit B, Ben-David E, Posen Y, et al. Effective Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme With Oncolytic Virotherapy: A Case-Series. Front Oncol 2020; 10: 702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, et al. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and T(regs) in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8(+) T cells. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5(200): 200ra116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cibrián D, Sánchez-Madrid F. CD69: from activation marker to metabolic gatekeeper. European journal of immunology 2017; 47(6): 946–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Virrey JJ, Guan S, Li W, Schonthal AH, Chen TC, Hofman FM. Increased survivin expression confers chemoresistance to tumor-associated endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 2008; 173(2): 575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakravarti A, Noll E, Black PM, et al. Quantitatively determined survivin expression levels are of prognostic value in human gliomas. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20(4): 1063–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, Yuan J, Zhang Z, Lin L, Xu S. Syndecan-1 expression in human glioma is correlated with advanced tumor progression and poor prognosis. Mol Biol Rep 2012; 39(9): 8979–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JW, Auffinger B, Spencer DA, et al. Single dose GLP toxicity and biodistribution study of a conditionally replicative adenovirus vector, CRAd-S-pk7, administered by intracerebral injection to Syrian hamsters. J Transl Med 2016; 14(1): 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohme M, Schliffke S, Maire CL, et al. Immunophenotyping of Newly Diagnosed and Recurrent Glioblastoma Defines Distinct Immune Exhaustion Profiles in Peripheral and Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24(17): 4187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu W, Wang W, Li H, et al. Single-Cell Atlas Reveals Complexity of the Immunosuppressive Microenvironment of Initial and Recurrent Glioblastoma. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah AH, Mahavadi A, Di L, et al. Survival benefit of lobectomy for glioblastoma: moving towards radical supramaximal resection. J Neurooncol 2020; 148(3): 501–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.