Abstract

Background

Cancer and its treatment can result in lifelong medical financial hardship, which we aimed to describe among adult survivors of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancers in the United States.

Methods

We identified adult (aged ≥18 years) survivors of AYA cancers (diagnosed ages 15-39 years) and adults without a cancer history from the 2010-2018 National Health Interview Surveys. Proportions of respondents reporting measures in different hardship domains (material [eg, problems paying bills], psychological [eg, distress], and behavioral [eg, forgoing care due to cost]) were compared between groups using multivariable logistic regression models and hardship intensity (cooccurrence of hardship domains) using ordinal logistic regression. Cost-related changes in prescription medication use were assessed separately.

Results

A total of 2588 AYA cancer survivors (median = 31 [interquartile range = 26-35] years at diagnosis; 75.0% more than 6 years and 50.0% more than 16 years since diagnosis) and 256 964 adults without a cancer history were identified. Survivors were more likely to report at least 1 hardship measure in material (36.7% vs 27.7%, P < .001) and behavioral (28.4% vs 21.2%, P < .001) domains, hardship in all 3 domains (13.1% vs 8.7%, P < .001), and at least 1 cost-related prescription medication nonadherence (13.7% vs 10.3%, P = .001) behavior.

Conclusions

Adult survivors of AYA cancers are more likely to experience medical financial hardship across multiple domains compared with adults without a cancer history. Health-care providers must recognize this inequity and its impact on survivors’ health, and multifaceted interventions are necessary to address underlying causes.

Cancer is the most common cause of disease-related death among adolescents and young adults (AYA) in the United States (1,2). Survival rates for AYA cancers have increased substantially in recent decades and now exceed 80% at 5 years after diagnosis (1,2). Cancer is still, however, a life-altering disease with well-described, long-term physical and psychological morbidities (“late effects”) as consequences of cancer and its treatment (3). The impact of these late effects on survivors’ abilities to attend school and gain and maintain employment, combined with residual costs from acute cancer care and ongoing costs associated with any late effects (4), has the potential to result in considerable financial hardship (5). Understanding the spectrum of medical financial hardship is critical to fully recognizing and addressing the impacts of cancer, even well after treatment and into later adulthood.

Medical financial hardship can be broadly categorized into 3 domains: material, psychological, and behavioral (6). Material hardship is typically measured by objective factors such as medical debt, out-of-pocket expenses for medical costs, or difficulty paying medical bills. Psychological hardship is the stress, distress, and worry that occurs over a current or future financial situation related to medical needs. Behavioral hardship captures actions such as delaying or forgoing medical care or treatment nonadherence because of concerns over costs. All domains contribute to the full burden of financial hardship that can affect survivors of cancer.

This burden, however, is not well characterized among adult survivors of AYA cancers. Much of our knowledge to date has been extrapolated from childhood cancer survivorship cohorts or studies of older adults, which may not be generalizable to the population of AYA cancer survivors specifically (7). We therefore sought to comprehensively evaluate medical financial hardship across material, psychological, and behavioral domains among adult survivors of AYA cancers in a large nationally representative sample.

Methods

Study Design and Outcome Measures

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a nationally representative, annual, cross-sectional household survey conducted in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States (8). It collects data on a broad range of health outcomes through in-person household interviews. We identified adults (aged ≥18 years at time of survey) who completed the NHIS between 2010 and 2018; during the study period, household response rates ranged from 64.2% to 82.0%. Respondents were classified as cancer survivors if they responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever been told by a physician or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” Age at and type of cancer diagnosis were asked in follow-up to an affirmative answer; we classified AYA cancers as those with an age at diagnosis between 15 and 39 years. Though there is variation in age limits selected to define the AYA population, an age range of 15-39 years is commonly used in North America (9,10). The comparison group included all adult NHIS participants who reported no history of cancer. This comparison maintains the nationally representative nature of the dataset examined (in contrast to matching the comparison group to demographic characteristics in the survivor group) and allows for comparisons that are reflective of the national population being studied. Statistical analyses adjusted for sample characteristics (including common demographic characteristics) to account for the effect of these factors on differences between groups (see below for details).

To avoid misinterpretation of survey questions about age at diagnosis, we focused on cancers more common in the AYA age group and excluded respondents who reported a diagnosis that would be unusual in the AYA population (based on incidence rates from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data) (11). Cervical cancer was reported at a rate inconsistent with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results prevalence data, and respondents reporting cervical cancer only were excluded given the increased likelihood that they had been diagnosed with a precancerous lesion or an abnormal screening Papanicolaou test result. Individuals reporting nonmelanoma skin cancer or skin cancer of unknown type only were also excluded.

Sample characteristics included age at survey, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, number of comorbid conditions, family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level, health insurance status, and geographic region.

Material financial hardship was defined as reporting problems paying medical bills in the preceding 12 months or paying off medical bills at the time of the survey. Psychological medical hardship was defined as reporting worry about medical costs of illness or accident or health care at the time of the survey and was dichotomized into hardship (“very worried” or “moderately worried”) or no hardship (“not too worried” or “not worried at all”). Behavioral hardship was defined as reporting delaying or forgoing medical care because of worry about cost, or being unable to afford prescription medicine, mental health care or counseling, dental care, eyeglasses, seeing a specialist, or follow-up care in the 12 months proceeding the time of the survey. A summary measure of whether respondents had any hardship in each domain of financial hardship was created. Hardship intensity was measured based on the number of cooccurring domains (2013-2018, when measures were collected more consistently in the NHIS).

Cost-related changes in prescription medication use, a measure of behavioral medical financial hardship, were measured consistently during 2013-2018 and therefore analyzed and presented separately. Changes in prescription medication use were divided into cost-related nonadherence (skipping doses, taking less medicine, or delaying prescription filling to save money) and cost-coping strategies (asking doctors for lower cost medications, buying prescription drugs from another country, or using alternative therapies to save money). Only respondents who had been prescribed medications in the preceding 12 months were surveyed on these measures. Summary measures of reporting any nonadherence or coping strategy behavior were created. Not all financial hardship measures were collected consistently across the entire study period; the distribution of survey questions with associated years surveyed and sample sizes are presented in Supplementary Table 1 (available online).

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics and compared between adults with and without a cancer history. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to generate adjusted proportions of respondents reporting individual and summary measures of material, psychological, and behavioral domains of medical financial hardship. All multivariable regression models were adjusted for age group, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, family income, health insurance status, number of comorbid conditions, survey year, and geographic region. Generalized ordinal logistic regression was used to generate and report adjusted proportions of number of hardship domains in describing medical financial hardship intensity.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to stratify cancer survivors by age at time of survey (aged < or ≥65 years) and time since cancer diagnosis (≤5, 6-15, 16-30, and ≥31 years) and to restrict the analysis to survivors who were 2 years and more from diagnosis and those with only 1 cancer diagnosis. Sensitivity analyses among survivors before and after Affordable Care Act (ACA) rollout (in 2014) were also conducted.

All analyses used NHIS sample weights and accounted for the complex NHIS design and survey nonresponse and were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) and Stata version 14.1 (College Station, TX). Statistical comparisons were 2-sided, with statistical significance defined as P less than .05. We did not adjust analyses for multiple comparisons and instead focused on patterns of statistical significance across measures. The NHIS deidentified data were publicly available, and approval for this study was obtained from the Hospital for Sick Children’s Research Ethics Board.

Results

We identified 2588 adult survivors of AYA cancers and 256 964 adults without a cancer history. Most cancer survivors had only 1 cancer diagnosis (91.6%), with a median age at cancer diagnosis of 31 years (interquartile range = 26-35 years). Substantial time had elapsed since cancer diagnosis for most survivors at time of survey, with 75.0% of survivors more than 6 years, 50.0% more than 16 years, and 25.0% more than 31 years from diagnosis. Survivors of AYA cancers were more likely to be younger, female, and non-Hispanic White compared with adults without a cancer history (Table 1). They were also more likely to have at least some college education, family income match 400% and more of the federal poverty level, public health insurance only, and more comorbid medical conditions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of adult survivors of AYA cancer and adults without a history of cancer, NHIS 2010-2018

| Sample Characteristic | AYA cancer survivorsWeighted %a(n = 2588) | Adults without a history of cancer Weighted %a(n = 256 964) | P b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of survey, y | |||

| 18-29 | 8.3 | 23.2 | <.001 |

| 30-39 | 23.0 | 18.3 | |

| 40-49 | 26.1 | 18.0 | |

| 50-64 | 27.4 | 25.1 | |

| 65-80 | 12.2 | 12.0 | |

| 81+ | 2.9 | 3.5 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 32.8 | 48.7 | <.001 |

| Female | 67.2 | 51.3 | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 77.6 | 64.3 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8.1 | 12.5 | |

| Hispanic | 10.6 | 16.2 | |

| Asian and others | 3.7 | 7.0 | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school or missing | 10.5 | 13.7 | .01 |

| High school graduate | 22.5 | 25.4 | |

| ≥Some college | 67.0 | 60.9 | |

| Marital status at time of survey | |||

| Not married or missing | 62.4 | 60.0 | .05 |

| Married | 37.6 | 40.0 | |

| Family income as % of FPL at time of survey | |||

| <200 | 26.6 | 29.1 | .004 |

| ≥200 and <400 | 25.7 | 27.1 | |

| ≥400 | 40.6 | 35.5 | |

| Missing | 7.1 | 8.4 | |

| Health insurance at time of survey | |||

| Age 18-64 y | |||

| Any private | 54.2 | 56.3 | <.001 |

| Public only | 19.9 | 13.5 | |

| Uninsured | 10.8 | 14.7 | |

| Age ≥65 y | |||

| Medicare and private | 7.7 | 6.9 | |

| Medicare with public | 2.2 | 2.2 | |

| Medicare only or uninsured | 5.2 | 6.4 | |

| No. of comorbid conditions at time of survey | |||

| 0 | 46.5 | 59.4 | <.001 |

| 1 | 29.4 | 27.0 | |

| 2 | 14.2 | 8.9 | |

| ≥3 | 9.9 | 4.7 | |

| Cancer diagnosis | |||

| Lymphoma | 7.8 | — | |

| Melanoma | 12.3 | — | |

| Testicular cancer | 5.5 | — | |

| Thyroid cancer | 9.1 | — | |

| Ovarian cancer | 7.3 | — | — |

| Uterine cancer | 10.8 | — | |

| Leukemia | 1.9 | — | |

| Breast cancer | 15.7 | — | |

| Time since diagnosis | |||

| <2 years | 8.4 | — | — |

| ≥2 years | 91.6 | — | |

| No. of cancer diagnoses | |||

| 1 only | 91.6 | — | — |

| 2-3 | 8.3 | — |

NHIS sample weights were applied to account for the complex study design and to reflect probability of selection, adjustments for nonresponse, and poststratification to provide nationally representative estimates. AYA = adolescent and young adult; FPL = federal poverty level; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey.

P values were calculated using the Pearson χ2 test statistic; statistical tests were 2-sided.

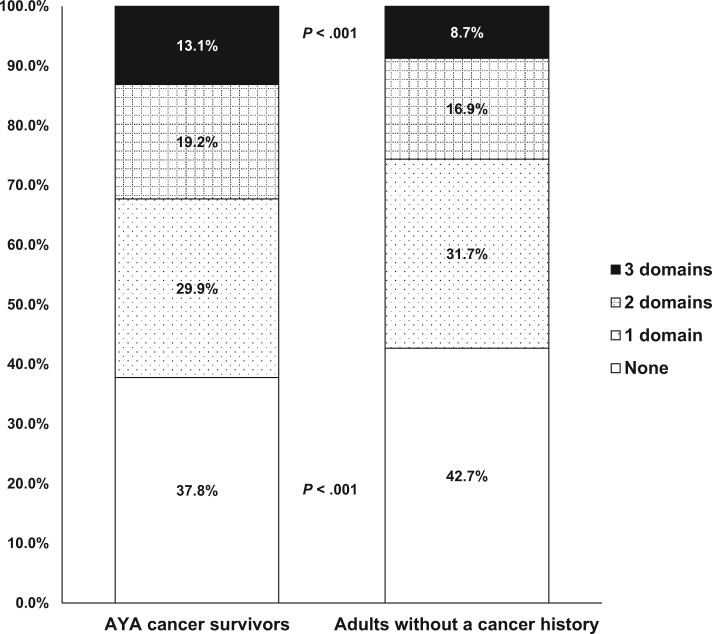

Cancer survivors were statistically significantly more likely to report problems paying medical bills in the preceding 12 months (22.0% vs 15.7%, P < .001) and were more likely to be paying off medical bills over time at time of survey (31.4% vs 22.9%, P < .001) compared with adults without a history of cancer in adjusted analyses (Table 2). Survivors were also more likely to endorse every single measure of behavioral hardship assessed, such as delaying or forgoing medical care due to worry about cost or being unable to afford specialist or follow-up care. Cancer survivors were statistically significantly more likely to report at least 1 measure of hardship in material (36.7% vs 27.7%, P < .001) and behavioral (28.4% vs 21.2%, P < .001) domains than individuals without a history of cancer. Survivors were also more likely to report worry about medical costs of health care (31.4% vs 28.7%, P = .047). The intensity of hardship was higher among cancer survivors, who were more likely to have hardship in all 3 domains (13.1% vs 8.7%, P < .001) and less likely to report no domains of hardship (37.8% vs 42.7%, P < .001) compared with those without a history of cancer (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Medical financial hardship in adult survivors of AYA cancer and adults without a history of cancer in the United States

| Medical financial hardship measure | AYA cancer survivors %a (95% CI) | Adults without a history of cancer %a (95% CI) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materialb | |||

| Problems paying medical bills | 22.0 (20.1 to 23.9) | 15.7 (15.4 to 15.9) | <.001 |

| Paying off medical bills over time | 31.4 (29.1 to 33.6) | 22.9 (22.6 to 23.2) | <.001 |

| Any material hardship | 36.7 (34.4 to 39.0) | 27.7 (27.4 to 28.0) | <.001 |

| Psychologicalc | |||

| Worried about medical costs of illness/accident | 44.2 (41.3 to 47.1) | 42.1 (41.7 to 42.5) | .15 |

| Worried about medical costs of health care | 31.4 (28.7 to 34.0) | 28.7 (28.3 to 29.0) | .047 |

| Any psychological hardship | 46.6 (43.6 to 49.5) | 44.7 (44.3 to 45.1) | .21 |

| Behavioral | |||

| Delayed medical care because of worry about costd | 13.6 (12.1 to 15.0) | 9.9 (9.8 to 10.1) | <.001 |

| Forgone medical care because of worry about costd | 9.8 (8.6 to 11.0) | 7.3 (7.2 to 7.5) | <.001 |

| Could not afford prescription medicined | 10.9 (9.6 to 12.2) | 7.4 (7.2 to 7.5) | <.001 |

| Could not afford mental health care/counselingd | 3.4 (2.7 to 4.2) | 2.3 (2.2 to 2.4) | .01 |

| Could not afford dental cared | 14.9 (13.4 to 16.4) | 12.3 (12.1 to 12.5) | .001 |

| Could not afford eyeglassesd | 8.9 (7.7 to 10.0) | 6.9 (6.7 to 7.0) | .001 |

| Could not afford to see a specialiste | 8.6 (7.2 to 9.9) | 4.6 (4.5 to 4.7) | <.001 |

| Could not afford follow-up caree | 7.2 (5.9 to 8.4) | 3.9 (3.8 to 4.0) | <.001 |

| Any behavioral hardshipd | 28.4 (26.3 to 30.6) | 21.2 (20.9 to 21.4) | <.001 |

Adjusted percentages and P values generated using multivariable logistic regression models with covariates: age group, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, family income, health insurance status, number of comorbid conditions, survey year, and geographic region; statistical comparisons were 2-sided. AYA = adolescent and young adult; CI = confidence interval; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey.

Material measures evaluated in NHIS 2011-2018; n (survivors) = 2347, n (comparison) = 232 140 for individual and summary measure(s).

Psychological measures evaluated in NHIS 2013-2018; n (survivors) = 1727, n (comparison) = 170 587 for individual and summary measure(s).

Selected behavioral measures evaluated in NHIS 2010-2018; n (survivors) = 2588, n (comparison) = 256 964 for these individual measures.

Selected behavioral measures evaluated in NHIS 2011-2017; n (survivors) = 2113, n (comparison) = 107 289 for these individual measures and summary measure for any behavioral hardship.

Figure 1.

Medical financial hardship intensity. Medical financial hardship intensity was measured by the co-occurrence of hardship domains. Adjusted percentages of number of hardship domains were generated using generalized ordinal logistic regression models with covariates: age group, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, family income, health insurance status, number of comorbid conditions, survey year, and geographic region. Measures in all domains were evaluated in National Health Interview Survey 2013-2018 (with the exception of measures of inability to afford to see a specialist or follow-up care, which were not measured in 2018). Sample sizes for hardship intensity comparisons were 1727 (survivors) and 170 587 (comparison group of adults without a cancer history). AYA = adolescent and young adult.

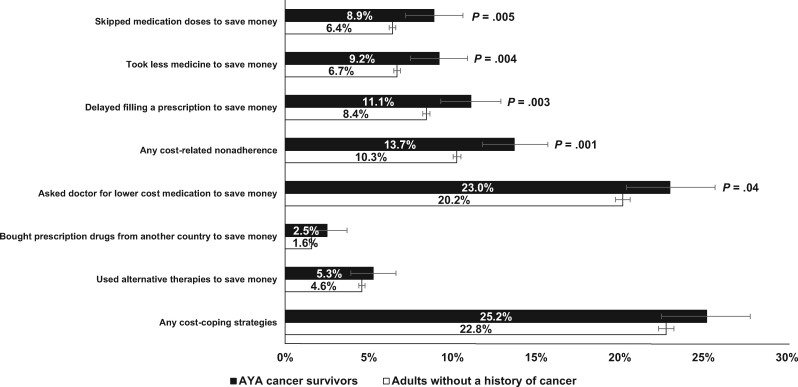

Survivors were statistically significantly more likely to report cost-related prescription medication nonadherence behaviors such as skipping medication doses, taking less medication, and delaying filling a prescription to save money; they were also more likely to report having asked a doctor for a lower-cost medication to save money (Figure 2). Compared with individuals without a history of cancer, survivors were also more likely to report at least 1 cost-related nonadherence (13.7% vs 10.3%, P = .001) behavior.

Figure 2.

Cost-related changes in prescription medication use in adult survivors of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer and adults without a history of cancer in the United States. Adjusted percentages were generated using multivariable logistic regression models with covariates: age group, sex, race or ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, family income, health insurance status, number of comorbid conditions, survey year, and geographic region. Measures of prescription medication use were evaluated in National Health Interview Survey 2013-2018; sample sizes for these comparisons were 1407 (survivors) and 107 289 (comparison group of adults without a cancer history).

Sensitivity analyses stratifying survivors by age younger than 65 years or 65 years and older at time of survey (Supplementary Table 2, available online) and time since diagnosis (Supplementary Table 3, available online), and those restricted to survivors 2 years or longer from diagnosis and with only 1 cancer diagnosis showed similar findings to the main analyses. Sensitivity analyses among survivors before and after the ACA rollout showed that estimates were similar pre- and post-ACA (Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Discussion

In a comprehensive evaluation of medical financial hardship in more than 2000 adult survivors of AYA cancer in the United States, we found that survivors were statistically significantly more likely than individuals without a history of cancer to experience specific financial hardships, such as difficulty paying medical bills, and experienced a higher intensity of financial hardship overall.

The burden of medical financial hardship across multiple domains among survivors has considerable implications for their health. The degree of behavioral medical financial hardship described is particularly concerning. Following acute cancer care, survivors may have physical late effects of treatment, such as cardiac disease following anthracycline therapy (12) or an increased risk of subsequent malignancies following radiation or chemotherapy (13). Survivors as a whole have more comorbid medical conditions (14,15) and increased prescription medication needs than individuals without a cancer history (16,17). Regular interactions with health-care providers and adherence to treatment for ongoing medical conditions are therefore critical to address and manage the medical complexity that exists among survivors. However, the behavioral manifestations of medical financial hardship—as captured by actions such as forgoing care and cost-related prescription medication nonadherence—directly diminish opportunities to mitigate survivors’ risks for ongoing and future health complications.

Material financial hardship may also directly affect health status, with survivors reporting material hardship also more likely to report physical symptoms (such as abnormal cardiac, pulmonary, or sensory function) (18) and lower overall quality of life in other studies (19). Psychological financial hardship has been associated with increased symptoms of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (18) and further adds to the poor mental health that some survivors may face as a complication following cancer treatment (20-22).

Material financial hardship has also been associated with difficulty obtaining health and life insurance and planning for retirement (18,23), which further perpetuates the cycle of financial burden for survivors and makes it more challenging for them to manage this burden. The ACA contains multiple components that could mitigate the financial hardship faced by AYA cancer survivors by increasing health insurance affordability and accessibility (24,25). These include allowing young adults to remain in their parents’ private health insurance plans as dependents until age 26 years, expanding Medicaid to low-income families, providing subsidies to low- and middle-income families purchasing private insurance on Marketplace, and eliminating preexisting condition exclusions and lifetime and annual coverage limits (26,27). The potential benefit of these provisions on financial hardship among survivors is especially relevant given the higher proportion of survivors who are uninsured or have public insurance only. Understanding the impact of these ACA provisions on medical financial hardship, particularly among survivors of AYA cancer, will be important for future research in the field.

Many factors can contribute to the financial burden experienced by cancer survivors. Acute cancer treatment and its late effects can lead to educational disruption (25,28), worse employment outcomes (29), productivity losses (30), and decreased income (31) among survivors. The impact of these factors is particularly challenging in AYA who are often pursuing or completing their education or entering the workforce and building their careers at the time of their cancer diagnosis (32). Disruptions at this critical point in the developmental trajectory from adolescence to independent adult life can have substantial ramifications on future productivity and financial resources (33). However, even after accounting for the effect of educational attainment, income, and insurance status in our adjusted analyses, adult survivors of AYA cancers disproportionately report more medical financial hardship. Further research is necessary to identify other factors that may influence the financial hardship experienced by cancer survivors (34), including additional sociodemographic characteristics (such as household composition and social support networks), the impact of medical or psychological comorbidities on coping responses to hardship, and other health systems factors (such as variations in primary care vs emergency department utilization).

The underlying causes that contribute to the development of medical financial hardship must also be addressed. At the health-care provider level, various strategies to support increased awareness and assessment of financial hardship (including educational and communication resources) and subsequent connection to existing financial and vocational assistance or support services (such as through dedicated social workers or patient navigators) have been described elsewhere (35,36). However, state and federal policies may have a broader impact, such as through the implementation of many provisions of the ACA in increasing health insurance coverage options, as well as affordability and accessibility. Another key area for intervention, particularly in light of our finding of statistically significant behavioral financial hardship related to prescription medication use, is in improving medication affordability—whether directly through the lowering of drug costs by pharmaceutical companies or through health insurance benefit design and reducing patient cost-sharing, including coinsurance and copayments, and out-of-pocket spending caps (37,38). A multifaceted approach at all levels is necessary to address the myriad contributors to financial hardship among AYA cancer survivors, and the impacts of such interventions require ongoing study to evaluate their effectiveness.

Our findings expand previous research among adult survivors of AYA cancers (39,40). Earlier work using a few years of NHIS data has shown similar findings of greater cost-related prescription medication nonadherence among AYA cancer survivors than adults without a cancer history, with nonadherence behaviors associated with uninsured status (41). Our study confirms the persistence of these findings over nearly a decade of data collection and extends previous research in the field by evaluating multiple measures within all domains of medical financial hardship and presenting a unique view of hardship intensity as conceptualized by the cooccurrence of multiple domains. Our findings add to such work completed among older cancer survivors, which also demonstrated increased hardship across multiple domains (42). However, given that much of our prior knowledge regarding AYA survivors has been drawn from studies on adolescents within childhood cancer survivor cohorts or young adults within largely adult-focused studies, with heterogeneity in outcomes selected to measure hardship, it is important that future research include specific AYA cohorts to facilitate understanding of the unique challenges faced by this group.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting this study’s findings. First, the self-reported nature of medical data collected through the NHIS introduces the possibility of reporting error. However, our study sample was limited to include respondents reporting an age at cancer diagnosis that would be consistent with existing epidemiologic data, and the ultimate distribution of diagnoses among our cohort of survivors is generally reflective of the more common cancer types among the AYA population (43). Furthermore, cancer survivors have been found to underreport their cancer history compared with objective medical registries (44). Our findings are therefore likely to understate the full burden of financial hardship among cancer survivors. Second, among individuals with a history of cancer, the NHIS does not distinguish between those receiving active treatment and longer-term survivors. However, most respondents in our survivor cohort (91.6%) were 2 or more years from diagnosis and likely no longer undergoing acute cancer care. Sensitivity analyses restricted to survivors who are 2 years or more from diagnosis showed similar findings to our main analyses. Third, the NHIS contains no questions about stage of disease at diagnosis or the details of cancer therapy. We are therefore unable to identify therapies or treatment modalities that may be correlated with financial hardship. Fourth, data on rurality are not publicly accessible within the NHIS and therefore could not be included in our analysis. However, the impact of rurality on financial hardship (45), and its interaction with other factors (such as race or ethnicity) that influence hardship (46), have been demonstrated among older cancer survivors and should be explored in future AYA-focused research on financial hardship among survivors. Future studies should also examine the impact of the ACA rollout, particularly as more data are obtained on the potential effect of expanding health-care access on financial hardship among cancer survivors. Last, we must note that our findings apply specifically to the health-care environment within the United States, though the pattern of findings may extend to other jurisdictions as well.

In conclusion, we found that adult survivors of AYA cancers are statistically significantly more likely to experience medical financial hardship than adults without a history of cancer. Understanding the spectrum of medical financial hardship is critical to those caring for and designing policies for adult survivors of AYA cancers and in guiding ongoing research in this area.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding or support for this work.

Notes

Role of the funder: Not applicable.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest or disclaimers to declare.

Author contributions: Conceptualization and methodology: ADL, ZZ, XH, JZ, KRY, PCN; Formal analysis: ZZ, RQ; Supervision: KRY, PCN; Writing (original draft): ADL; Writing (review and editing): ADL, ZZ, XH, JZ, KRY, PCN.

Prior presentations: This manuscript has not been published previously. This work has been presented as an oral presentation at the 2019 International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) Conference.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are publicly available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A.. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA.. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(5):495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robison LL, Hudson MM.. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(1):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Allaire BT, Ekwueme DU, Poehler D, et al. Breast cancer treatment costs in younger, privately insured women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(2):429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaul S, Kirchhoff AC.. Closing the financial toxicity gap for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(7):e27742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nathan PC, Henderson TO, Kirchhoff AC, Park ER, Yabroff KR.. Financial hardship and the economic effect of childhood cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(21):2198–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fidler MM, Frobisher C, Hawkins MM, Nathan PC.. Challenges and opportunities in the care of survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(6):e27668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey 2017. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. Accessed March 11, 2019.

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer - report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. 2006. https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya/research/ayao-august-2006.pdf. Accessed April 2019.

- 10. Smith AW, Seibel NL, Lewis DR, et al. Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: an update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer. 2016;122(7):988–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/index.html. Accessed April 28, 2019.

- 12. Chen Y, Chow EJ, Oeffinger KC, et al. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors and individual prediction of cardiovascular events in childhood cancer survivors. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(3):256–265. doi:10.1093/jnci/djz108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JS, DuBois SG, Coccia PF, Bleyer A, Olin RL, Goldsby RE.. Increased risk of second malignant neoplasms in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(1):116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gibson TM, Mostoufi-Moab S, Stratton KL, et al. Temporal patterns in the risk of chronic health conditions in survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed 1970-99: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1590–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smitherman AB, Mohabir D, Wilkins TM, Blatt J, Nichols HB, Dusetzina SB.. Early post-therapy prescription drug usage among childhood and adolescent cancer survivors. J Pediatr. 2018;195:161–168.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kero AE, Madanat‐Harjuoja LM, Järvelä LS, Malila N, Matomäki J, Lähteenmäki PM.. Cardiovascular medication after cancer at a young age in Finland: a nationwide registry linkage study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(3):683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang I-C, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, et al. Determinants and consequences of financial hardship among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(2):189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang I-C, Brinkman TM, Kenzik K, et al. Association between the prevalence of symptoms and health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4242–4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Recklitis CJ, Diller LR, Li X, Najita J, Robison LL, Zeltzer L.. Suicide ideation in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwak M, Zebrack BJ, Meeske KA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: a 1-year follow-up study: post-traumatic stress in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1798–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zheng Z, Han X, Zhao J, Yabroff KR.. What can we do to help young cancer survivors minimize financial hardship in the United States? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19(8):655–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Lynch CF, et al. Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2393–2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Virgo KS, Bromberek JL, Glaser A, Horgan D, Maher J, Brawley OW.. Health care policy and cancer survivorship: health care policy and cancer survivorship. Cancer. 2013;119(Suppl):2187–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The coverage provisions in the Affordable Care Act: an update. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/ issue-brief/the-coverage-provisions-in-the-affordable-care-act-anupdate/. Accessed November 27, 2019.

- 28. Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, et al. Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97(4):1115–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirchhoff AC, Krull KR, Ness KK, et al. Occupational outcomes of adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2011;117(13):3033–3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guy GP, Berkowitz Z, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Yabroff KR.. Annual economic burden of productivity losses among adult survivors of childhood cancers. Pediatrics. 2016;138(Supplement):S15–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wengenroth L, Sommer G, Schindler M, et al. Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group (SPOG). Income in adult survivors of childhood cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stone DS, Ganz PA, Pavlish C, Robbins WA.. Young adult cancer survivors and work: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(6):765–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meernik C, Kirchhoff AC, Anderson C, et al. Material and psychological financial hardship related to employment disruption among female adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2020;127(1):137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lau N, Bona K, Steineck A, Rosenberg AR.. What we did not learn from an exploratory analysis of economic hardship in newly diagnosed adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(12):e27411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salsman JM, Bingen K, Barr RD, Freyer DR.. Understanding, measuring, and addressing the financial impact of cancer on adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(7):e27660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Zafar SY, Shih YT.. Time to add screening for financial hardship as a quality measure? CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;doi:10.3322/caac.21653. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yousuf Zafar S. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Robin Yabroff K, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Rai A, Han X.. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: what do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(12):1389–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. Financial burden in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3474–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(6):1024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaul S, Avila JC, Mehta HB, Rodriguez AM, Kuo Y-F, Kirchhoff AC.. Cost-related medication nonadherence among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: medication nonadherence among AYA cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123(14):2726–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125(10):1737–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG, Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975-2000. 2006. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/publications/aya/aya_mono_complete.pdf. Accessed March 2019.

- 44. Desai MM, Bruce ML, Desai RA, Druss BG.. Validity of self-reported cancer history: a comparison of health interview data and cancer registry records. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(3):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zahnd WE, Davis MM, Rotter JS, et al. Rural-urban differences in financial burden among cancer survivors: an analysis of a nationally representative survey. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(12):4779–4786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spencer JC, Rotter JS, Eberth JM, et al. Employment changes following breast cancer diagnosis: the effects of race and place. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(6):647–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are publicly available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.