Key Points

Question

Does the daily use of 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride for the management of adults with a recent stroke decrease the prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression over 26 weeks?

Findings

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 1221 patients, the routine daily use of 20 mg of fluoxetine for 26 weeks did not reduce the proportion of those with a recent stroke who developed clinically significant symptoms of depression compared with placebo (20% vs 21%).

Meaning

Patients with recent stroke should not be treated routinely with 20 mg daily of fluoxetine to prevent or treat clinically significant symptoms of depression during the first 6 months after the stroke.

Abstract

Importance

One in 3 adults experiences clinically significant symptoms of depression during the first year after a stroke, but evidence to support the use of antidepressants in this population remains scant.

Objective

To investigate whether daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride reduces the proportion of people affected by clinically significant symptoms of depression after stroke.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this secondary analysis of the Assessment of Fluoxetine in Stroke Recovery parallel-group, randomized (1:1 assignment), double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, 1221 participants in Australia, New Zealand, and Vietnam were recruited between January 11, 2013, and June 30, 2019, and were followed up for 6 months. Adults aged 18 years or older were recruited 2 to 15 days after experiencing a stroke associated with modified Rankin Scale score of 1 or higher.

Interventions

Fluoxetine hydrochloride, 20 mg, or matched placebo daily for 26 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

A 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score of 9 or lower was a prespecified secondary outcome of the trial. Assessments were completed at baseline and at 4, 12, and 26 weeks. Other outcomes of interest included participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression, prescription of a nontrial antidepressant, or nonpharmacologic treatment of depression. Analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results

A total of 607 participants (378 men [62.3%]; mean [SD] age, 64.3 [12.2] years) were randomly assigned treatment with placebo, and 614 participants (397 men [64.7%]; mean [SD] age, 63.4 [12.4] years) were randomly assigned treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride daily. The groups were balanced for demographic and clinical measures. At baseline, 112 patients (18.5%) in the placebo group and 116 patients (18.9%) in the fluoxetine group had PHQ-9 scores of 9 or higher. During follow-up, 126 of 596 participants (21.1%) treated with placebo and 121 of 598 participants (20.2%) treated with fluoxetine had PHQ-9 scores of 9 or higher (P = .70). A similar proportion of participants with PHQ-9 scores less than 9 at baseline who were treated with fluoxetine hydrochloride and placebo developed PHQ-9 scores of 9 or higher during the trial (placebo, 72 of 488 [14.8%]; and fluoxetine, 63 of 485 [13.0%]; P = .43). A slightly higher number of participants in the placebo group than in the fluoxetine group had a participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression (42 of 602 [7.0%] vs 26 of 601 [4.3%]; P = .05). By week 26, 14 participants (2.3%) in the placebo group and 12 participants (1.9%) in the fluoxetine group had died (P = .67).

Conclusions and Relevance

Routine daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine did not decrease the proportion of people affected by clinically significant symptoms of depression after a stroke, nor did it affect the proportion of people prescribed an antidepressant or receiving nonpharmacologic treatments compared with placebo.

Trial Registration

http://anzctr.org.au Identifier: ACTRN12611000774921

This randomized clinical trial investigates whether daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride reduces the proportion of people affected by symptoms of depression after stroke.

Introduction

Depression affects 1 in every 3 people during the first year after a stroke.1 Evidence from trials suggests that the use of antidepressants reduces the prevalence of depression after stroke, although the number, size, and quality of studies is limited and difficult to generalize.2 Fluoxetine hydrochloride, a widely used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, is more efficacious than placebo to treat depression in adults,3 and its role in the management of people at risk of depression, such as stroke survivors, has attracted interest because of the results of the FLAME (Fluoxetine for Motor Recovery After Acute Ischaemic Stroke) trial.4 The FLAME trial randomly assigned 118 adults who had a recent stroke to receive daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine or placebo for 3 months. Treatment with fluoxetine enhanced motor recovery and decreased the proportion of those with depression compared with placebo (7% vs 29%).

A systematic review summarized the results of 6 small studies investigating the effect of fluoxetine on the mood of patients who had had a stroke,5 but only 2 studies were placebo controlled. Dam and colleagues6 randomly assigned participants who had had a stroke to receive fluoxetine hydrochloride 20 mg daily (n = 16) or placebo (n = 16). After 3 months, the treatment groups did not differ in the scores of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Robinson and colleagues7 randomly assigned 27 adults who had had a stroke to receive fluoxetine hydrochloride (≤40 mg daily) and 28 to receive placebo for 12 weeks. They found that fluoxetine did not improve the mood of participants without depression and might have worsened the mood of those who had depression at baseline compared with placebo.

More recently, 3 large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials have examined the effect of fluoxetine on patients who had a stroke, with depression recorded as a secondary outcome of interest. The FOCUS (Fluoxetine or Control Under Supervision) trial randomized 3127 adults,8 the EFFECTS (Efficacy of Fluoxetine—a Randomised Controlled Trial in Stroke) randomized 1500 participants,9 and the AFFINITY (Assessment of Fluoxetine in Stroke Recovery) trial randomized 1280 participants10 to receive daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride or matching placebo for 6 months. Fluoxetine did not improve functional outcomes, but FOCUS8 and EFFECTS9 found that fluoxetine reduced the prevalence of depression. The pragmatic definition of depression used in these studies—nonstructured clinician diagnosis of depression—has uncertain validity. The AFFINITY trial10 used the validated 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to assess depressive symptoms.11 We hypothesized that, compared with placebo, a lower proportion of participants treated with fluoxetine would experience clinically significant symptoms of depression or would receive other pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatments for clinically significant symptoms of depression over 6 months. We also expected treatment with fluoxetine to reduce the prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression among those who had clinically significant symptoms of depression at baseline, as well as the cumulative incidence of clinically significant symptoms of depression among those free of clinically significant symptoms of depression at the start of the trial.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The AFFINITY trial was a randomized, parallel-group (1:1), double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of fluoxetine for the management of adults aged 18 years or older who had a recent stroke (trial protocol in Supplement 1). Participants were recruited between January 11, 2013, and June 30, 2019, The primary outcome of the trial was functional ability after 6 months of treatment, with clinically significant symptoms of depression being a planned secondary end point.12 Details about the recruitment and the intervention have been published10 and are briefly summarized. We recruited adults in contact with stroke services in Australia, New Zealand, and Vietnam—they, or their legal surrogates, provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Royal Perth Hospital Ethics Committee, and all participating sites received ethics committee and institutional approval from their respective boards.

Participants were 18 years of age or older with a clinical diagnosis of stroke 2 to 15 days before randomization. They had a neurologic deficit that resulted in a modified Rankin Scale score of 1 or higher (range, 0-6, where 0 indicates no signs or symptoms and 6 indicates death).13 We excluded people with a history of epilepsy, bipolar disorder, hepatic or renal impairment, or hyponatremia or who had used antipsychotic medications or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors within the last month, as well as those with a life-threatening illness who were pregnant or of childbearing potential and not taking adequate contraception or who were enrolled in another trial. We excluded from the analyses participants for whom no baseline PHQ-9 data were available.

Intervention, Randomization, and Masking

Participants were randomized via a password-protected web-based randomization service. A minimization algorithm was used to reduce group imbalance and to assign participants to 6 months’ treatment with fluoxetine hydrochloride, 20 mg, or placebo once a day in a 1:1 ratio. The investigators, participants, their caregivers, and assessors were masked to the treatment assignment. Placebo and fluoxetine capsules were indistinguishable even when broken. Additional details have been reported alongside the results of the primary analyses of the trial.10

Outcome Measures and Follow-up Assessments

Depressive symptoms were measured with the PHQ-9, a self-administered scale that consists of 9 items assessing signs and symptoms that may have occurred during the preceding 2 weeks, with each item scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).11 The PHQ-9 total scores can range from 0 (no symptoms) to 27 (most symptoms). Scores of 9 or higher indicate the presence of clinically significant symptoms of depression among patients who had a stroke.14 The scale has robust psychometric properties,11 and its scores are sensitive to change over time.15 We assessed participants at baseline and at 4, 12, and 26 weeks.

Other baseline measures included age (in years), sex, country of residence, living arrangements (living alone or with others), use of antidepressants (yes or no), nonpharmacologic treatment of depression (yes or no), and past (before stroke) or current treatment of depression (yes or no). We used the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale to assess neurologic deficits16 and the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project clinical classification of strokes.17

We recorded the use of nontrial antidepressants or other treatments for depression (eg, psychological intervention) as well as the participant-reported clinician-disclosed diagnosis of depression between assessments (weeks 4, 12, and 26). We assessed adherence to trial medication through pill counts and by asking participants “On average, since the last follow-up, how many times per week was the trial medication taken?” We considered that participants had shown good adherence if they had used the trial medication for 5 to 7 days per week, on average. Loss to follow-up and adverse events were also recorded at each assessment.

Study Power

The trial was designed to have 90% power to detect an absolute increase in the proportion of participants with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0 to 2 at 6 months from 50% to 57.5%.10 With a sample size of 1280 people, the study had 80% power to declare a significant absolute reduction of 7% in the risk of depression.

Statistical Analysis

We used Stata, version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC) to manage and analyze deidentified data. Primary analysis was performed on an intent-to-treat basis. Descriptive statistics summarized the data as counts and proportions (categorical variables) or mean (SD) values in the case of numerical continuous measures or median values and interquartile ranges for ordinal data. Between-group comparisons used Pearson χ2 statistics and t tests. We used proportion tests to calculate differences between groups and repeated-measures logit models to estimate the effect of treatment on clinically significant symptoms of depression over 26 weeks. We used multilevel mixed regression models to estimate the effect of the intervention on PHQ-9 scores over time. We completed sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of the intervention when a cut point score of 14 or 15 on the PHQ-9 was used to define depression or to determine the effect of the intervention in preventing clinically significant symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 score <9 at baseline) and treating clinically significant symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 score ≥9 at baseline). Further analyses examined the effect of optimal adherence on outcomes of interest. Given the diverse origins of participants, we also investigated the effect of country of origin on the prevalence of the outcomes of interest. We used the κ statistic to measure agreement between participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression and depression defined by a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher. We interpreted results with a κ statistic of 0.01 to 0.20 as none to slight agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 as some agreement, 0.41 to 0.60 as moderate agreement, 0.61 to 0.80 as substantial agreement, and 0.81 to 1.00 as nearly perfect agreement. The α level was set at 5%, and all probability estimates were derived from 2-tailed tests.

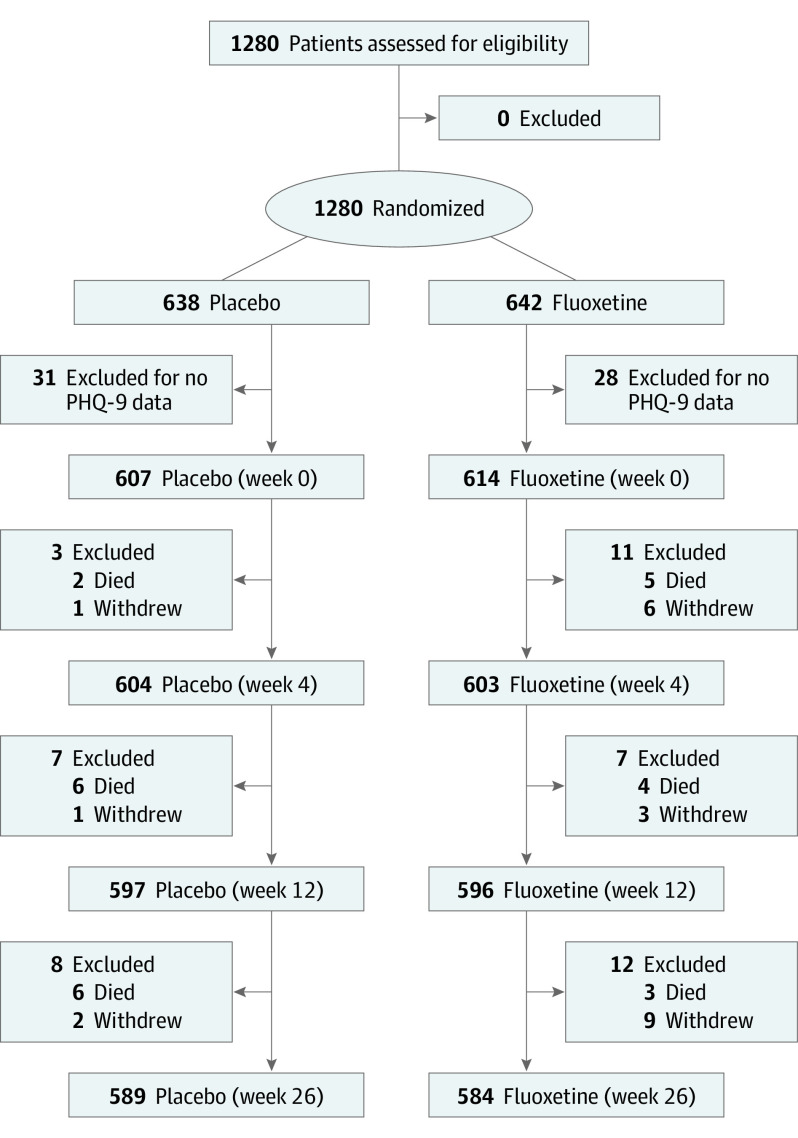

Results

We randomly assigned 1280 adults to receive treatment with placebo (n = 638) or fluoxetine (n = 642). Of these, 607 in the placebo group (378 men [62.3%]; mean [SD] age, 64.3 [12.2] years) and 614 in the fluoxetine group (397 men [64.7%]; mean [SD] age, 63.4 [12.4] years) completed the PHQ-9 at baseline and were included in the main analyses. Compared with the 59 people who did not complete the PHQ-9, the 1221 study participants were younger, more likely to be male, more likely to be from Vietnam, less likely to be living alone, and less likely to have a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of higher than 15 (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Participants’ median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 6 (interquartile range, 3-8). Figure 1 depicts the flow of participants during the trial, and Table 1 summarizes their baseline characteristics. The groups were balanced for all baseline measures; 112 participants (18.5%) in the placebo group and 116 participants (18.9%) in the fluoxetine group had clinically significant symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 score ≥9) (P = .84). The mean (SD) PHQ-9 score was 4.9 (4.1) for participants in the placebo group and 4.8 (4.3) for participants in the fluoxetine group (P = .80).

Figure 1. Flow of Participants During the AFFINITY (Assessment of Fluoxetine in Stroke Recovery) Trial.

PHQ indicates Patient Health Questionnaire.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants Who Completed the PHQ-9 at the Time of Randomizationa.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 607) | Fluoxetine (n = 614) | ||

| Age, y | |||

| <60 | 221 (36.4) | 226 (36.8) | .64 |

| 60-69 | 179 (29.5) | 193 (31.4) | |

| ≥70 | 207 (34.1) | 195 (31.8) | |

| Male | 378 (62.3) | 397 (64.7) | .39 |

| Origin | |||

| Vietnam | 352 (58.0) | 339 (55.2) | .56 |

| Australia | 238 (39.2) | 254 (41.4) | |

| New Zealand | 17 (2.8) | 21 (3.4) | |

| Living alone | 71 (11.7) | 70 (11.4) | .87 |

| NIHSS score | |||

| <5 | 255 (42.0) | 238 (38.8) | .48 |

| 5-15 | 337 (55.5) | 362 (59.0) | |

| >15 | 15 (2.5) | 14 (2.3) | |

| Ischemic strokec | 517 (85.3) | 526 (86.1) | .70 |

| Classification | |||

| Uncertaind | 91 (15.0) | 90 (14.7) | .81 |

| LACS | 103 (17.0) | 114 (18.6) | |

| PACS | 274 (45.1) | 258 (42.0) | |

| POCS | 103 (17.0) | 113 (18.4) | |

| TACS | 36 (5.9) | 39 (6.4) | |

| Depression treatment | |||

| Previous | 18 (3.0) | 30 (4.9) | .08 |

| Current | 16 (2.6) | 15 (2.4) | .83 |

Abbreviations: LACS, lacunar syndrome; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PACS, partial anterior circulation syndrome; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; POCS, posterior circulation syndrome; TACS, total anterior circulation syndrome.

A total of 59 participants who did not complete the PHQ-9 at randomization were excluded from all analyses.

Derived from analysis of contingency tables using the Pearson χ2 statistic.

Information not available for 4 participants (1 in the placebo group and 3 in the fluoxetine group).

Includes cases for which this information was missing and cases of hemorrhagic stroke.

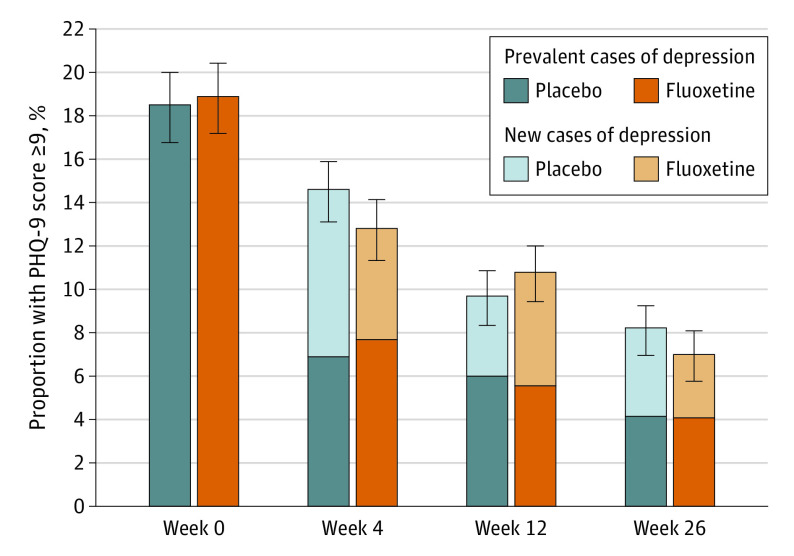

Primary Outcome

Figure 2 illustrates the results of the primary analysis of the study. After 4 weeks, 14.6% of participants in the placebo group (85 of 583) and 12.8% in the fluoxetine group (76 of 592) had a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher. After 12 weeks, 9.7% of participants in the placebo group (56 of 579) and 10.8% of participants in the fluoxetine group (62 of 576) had a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher. At 26 weeks, 8.2% of participants in the placebo group (47 of 575) and 7.0% of participants in the fluoxetine group (39 of 555) had a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher. Logit analysis for panel data showed that the proportion of participants with a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher decreased with time (odds ratio [OR], 0.96; 95% CI, 0.80-1.27; P < .001), that the main effect of treatment group was not significant (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.27; P = .94), nor was the interaction between treatment group and time (interaction between fluoxetine treatment and week 4: OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.59-1.20; P = .34; interaction between fluoxetine treatment and week 12: OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.79-1.71; P = .46; and interaction between fluoxetine treatment and week 26: OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.54-1.28; P = .41). Mixed-model regression showed that treatment with fluoxetine had no effect on PHQ-9 total score over time (mean treatment effect of fluoxetine on PHQ-9 scores over time, –0.08; 95% CI, –0.41 to 0.25; P = .64). The cumulative prevalence of participants with PHQ-9 scores of 9 or higher after baseline was 21.1% among the placebo group (126 of 596) and 20.2% among the fluoxetine group (121 of 598) (P = .70) (Table 2). Male sex (interaction OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.41-1.09; P = .11), the type of stroke (ischemic vs hemorrhagic: interaction OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.52-2.01; P = .94), history of depression (interaction OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.33-2.59; P = .87), and study site (Australia and New Zealand vs Vietnam: interaction OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.58-1.51; P = .77) had no effect on the depression outcome. eTable 5 in Supplement 2 shows the results of the analysis including participants for whom baseline PHQ-9 score was not available.

Figure 2. Proportion of Participants With a 9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) Total Score of 9 or Higher During the Trial.

Error bars indicate the SE of the proportions, darker colors indicate prevalent cases of depression, and lighter colors indicate new cases of depression.

Table 2. Proportion of Participants With Depression-Related Outcomes Over a Period of 26 Weeks After Baseline According to Treatment Assignmenta.

| Outcome | Participants, No. (%) | Mean difference, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 607) | Fluoxetine (n = 614) | ||

| PHQ-9 score ≥9b | 126 (21.1) | 121 (20.2) | 0.9 (−3.7 to 5.5) |

| Participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depressionc | 42 (7.0) | 26 (4.3) | 2.7 (0.5 to 5.3)d |

| Nontrial antidepressant usee | 49 (8.1) | 43 (7.2) | 1.0 (−2.0 to 4.0) |

| Nonpharmacologic treatmentc | 17 (2.8) | 19 (3.2) | −0.3 (−2.3 to 1.6) |

| Any depressive outcomec,f | 153 (25.4) | 144 (24.0) | 1.5 (−3.4 to 6.3) |

Abbreviation: PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Excludes baseline data.

Information missing for 11 participants in the placebo group and 16 participants in the fluoxetine group.

Information missing for 5 participants in the placebo group and 13 participants in the fluoxetine group.

P = .046.

Information missing for 5 participants in the placebo group and 14 participants in the fluoxetine group.

Any depressive outcome: PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher or diagnosis of depression or antidepressant use or nonpharmacologic treatment at any of the assessments at weeks 4, 12, or 26.

Secondary Outcomes

The proportion of participants using nontrial antidepressants or nonpharmacologic treatments for depression was similar for both groups (Table 2), although a slightly higher number of participants in the placebo group than in the fluoxetine group had a participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression (42 of 602 [7.0%] vs 26 of 601 [4.3%]; P = .05). A PHQ-9 score of 15 or higher was recorded by 2.7% of participants (16 of 596) in the placebo group and 2.2% of participants (13 of 598) in the fluoxetine group during follow up (P = .57). Agreement between a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher and participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression was poor (κ = 0.19).

Table 3 summarizes the data for participants who did not have clinically significant symptoms of depression at baseline. Logit analysis of panel data show that the proportion of participants with a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher decreased with time (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97-1.00; P = .02), that the main effect of treatment was not significant (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.60-1.25; P = .44), and the interaction between treatment and time was not significant. The proportion of these participants treated with placebo and fluoxetine who scored 9 or higher on the PHQ-9 at 1 or more of the follow-up assessments was 72 of 488 (14.8%) and 63 of 485 (13.0%), respectively. Of the 228 participants with clinically significant symptoms of depression at baseline, 45 of 108 (41.7%) of those treated with placebo and 46 of 111 (41.4%) of those treated with fluoxetine still had clinically significant symptoms of depression by week 4 (P = .97). The proportion of participants with clinically significant symptoms of depression continued to derease with time; 29.0% (31 of 107) of those in the placebo group and 29.6% (32 of 108) of those in the fluoxetine group had clinically significant symptoms of depression by week 12 (P = .92), and 19.8% (21 of 106) of those in the placebo group and 18.7% (20 of 107) of those in the fluoxetine group had clinically significant symptoms of depression by the end of week 26, but the effect of treatment with fluoxetine was not statistically significant compared with placebo (P = .84).

Table 3. Proportion of Participants With Depression-Related Outcomes Over a Period of 26 Weeks After Baseline Among Those Who Were Free of Clinically Significant Symptoms of Depression (PHQ-9 Score <9) at Baselinea.

| Outcome | Participants, No. (%) | Mean difference, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 495) | Fluoxetine (n = 498) | ||

| PHQ-9 score ≥9b | 72 (14.8) | 63 (13.0) | 1.8 (−2.6 to 6.1) |

| Participant-reported diagnosis of depressionc | 31 (6.3) | 20 (4.1) | 2.2 (−0.6 to 5.1) |

| Nontrial antidepressant used | 40 (8.2) | 35 (7.2) | 1.0 (−2.4 to 4.3) |

| Nonpharmacologic treatmentc | 14 (2.8) | 15 (3.1) | −0.2 (−2.4 to 1.9) |

| Any depressive outcomec,e | 94 (19.1) | 84 (17.2) | 1.9 (−2.9 to 6.7) |

Abbreviation: PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Excludes baseline data.

Information missing for 7 participants in the placebo group and 13 participants in the fluoxetine group.

Information missing for 4 participants in the placebo group and 11 participants in the fluoxetine group.

Information missing for 5 participants in the placebo group and 12 participants in the fluoxetine group.

Any depressive outcome: PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher or diagnosis of depression or antidepressant use or nonpharmacologic treatment at any of the assessments at weeks 4, 12, or 26.

Other Outcomes

By week 26, 14 participants (2.3%) treated with placebo and 12 (2.0%) of those treated with fluoxetine had died (P = .67). Another 22 participants did not complete all of the assessments: 4 (0.7%) in the placebo group and 18 (2.9%) in the fluoxetine group (P = .003). Harms associated with the intervention have been reported elsewhere.10 Among participants who were alive and remained in the study for 26 weeks, adequate adherence to placebo treatment and adherence to fluoxetine treatment were 85.7% (503 of 587) and 86.4% (502 of 581), respectively (P = .72). eTable 3 in Supplement 2 shows the baseline characteristics of participants with or without a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher, and eTable 4 in Supplement 2 shows the baseline characteristics of participants without clinically significant symptoms of depression at baseline who remained free of clinically significant symptoms of depression or developed clinically significant symptoms of depression during the trial. A similar proportion of participants treated with fluoxetine and participants treated with placebo developed new cases of depression.

We then restricted the primary analysis to 385 participants in the placebo group and 388 in the fluoxetine group who had completed the 26 weeks of the trial and had shown good adherence to treatment (per-protocol analysis). Of these participants, 12.2% (47 of 385) of those treated with placebo and 9.8% (38 of 388) of those treated with fluoxetine had PHQ-9 scores of 9 or higher at some point during the 26 weeks of the trial (mean difference, 2.4%; 95% CI, −2.0% to 6.8%; P = .28).

Finally, we examined the effect of study site on the outcomes of interest; 691 of 1221 patients (56.6%) were from Vietnam, 492 of 1221 patients (40.3%) were from Australia, and 38 of 1221 patients (3.1%) were from New Zealand (eTable 2 and eFigure in Supplement 2). Compared with participants from Vietnam, those from Australia had higher odds of having a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10-1.96), a participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression (OR, 14.66; 95% CI, 6.26-34.33), use of nontrial antidepressants (OR, 5.29; 95% CI, 3.13-8.96), and nonpharmacologic treatment of depression (OR, 8.27; 95% CI, 3.17-21.58) during the trial.

Discussion

A total of 184 of 607 participants (30.3%) treated with placebo and 179 of 314 participants (29.1%) treated with fluoxetine recorded a PHQ-9 score of 9 or higher at some point during follow up (P = .66). Daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride did not decrease the cumulative proportion of participants with clinically significant symptoms of depression, nor did it affect the proportion of participants prescribed a nontrial antidepressant or nonpharmacologic treatments. More participants treated with placebo than fluoxetine reported being told they had depression by a clinician, although the prevalence of a participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression was low in both groups compared with those meeting the PHQ-9 definition of depression. Our findings also show that treatment with fluoxetine did not prevent the emergence of depressive symptoms in this population nor was it more effective than placebo in treating depression among those with clinically significant symptoms of depression at baseline.

FOCUS, the largest fluoxetine trial of individuals with stroke published to date, reported that depression affected 17% of participants treated with placebo and 13% of those treated with fluoxetine.8 The EFFECTS trial excluded patients with prevalent cases of depression and found that treatment with fluoxetine reduced the proportion of patients who developed depression: 11% of those treated with placebo and 7% of those treated with fluoxetine.9 The proportion of participants with clinically significant symptoms of depression in the AFFINITY trial was lower than that described for FOCUS and EFFECTS, partly because clinically significant symptoms of depression were relatively uncommon among participants recruited from Vietnam. The reasons behind such a discrepancy are not clear, but evidence from other studies suggests that depression is more prevalent among Australian adults than Vietnamese people living in Vietnam or Australia.18 This finding would have moved our results toward the null hypothesis. Overall, the absolute risk reduction of PHQ-9 scores of 9 or higher associated with the use of fluoxetine in AFFINITY was 1.1%. A large proportion of AFFINITY participants with clinically significant symptoms of depression at baseline no longer had clinically significant symptoms of depression at week 4, which may suggest that the affective symptoms that emerge during the first few weeks after a stroke are physiologically unstable and may represent a self-limited adjustment disorder with depressive symptoms. Should that be the case, the introduction of an antidepressant during the acute poststroke period may not be helpful.

FOCUS, EFFECTS, and AFFINITY have shown that daily treatment with 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride for 6 months increases the risk of bone fractures.8,9,10 This finding would suggest that the use of fluoxetine to prevent poststroke depression should be considered only if the evidence of benefit outweighs the potential risk of harm.19 Although the results of these trials suggest that fluoxetine reduces the proportion of patient who had a stroke and received a clinical diagnosis of depression, our data using repeated assessments with a valid depression instrument failed to replicate these results and showed that agreement between the PHQ-9 definition of depression and participant-reported diagnosis of depression is poor. This finding could indicate poor sensitivity of clinicians involved in the care of patients with stroke to recognize cases of depression, reluctance of participants to disclose a diagnosis of depression, or the differing time frames used for the assessments (since last assessment vs during the last 2 weeks for the PHQ-9), or it could be due to the poor specificity of the PHQ-9 in identifying true cases of depression among patients who had a stroke. EFFECTS clinicians used a nonstructured clinical assessment that was guided by the DSM-IV and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale to measure the severity of symptoms among those deemed to have depression, but only those who were thought to have depression after the clinical assessment were evaluated with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.12 The diagnosis of depression in FOCUS relied on a participant-reported clinician diagnosis of depression and the use of the 5-item Mental Health Inventory, but the assessment of depressive symptoms was not systematic (no structured clinical interview or validated depression scales were used).12 Hence, despite study similarities, it is difficult to compare the trajectory of depressive symptoms over 6 months in AFFINITY, EFFECTS, and FOCUS. Trial evidence suggesting that other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may reduce the prevalence of depression after stroke is not compelling.2,20,21,22

Strengths and Limitations

This study has some strengths. AFFINITY generated high-quality data using a validated instrument for the assessment and diagnosis of clinically significant symptoms of depression after stroke and a study design that minimized bias and confounding. Loss to follow-up was low, and adherence to the intervention was appropriate.

This study also has some limitations. We recruited medically stable patients who had mild to moderate deficits, which may have contributed to the relatively modest number of people who developed clinically significant symptoms of depression during this trial compared with FLAME.4 We found that participants with severe neurologic deficits were less likely to complete the PHQ-9, so that our results apply primarily to patients with stroke who had mild to moderate neurologic deficits. The PHQ-9, albeit valid for the assessment of depression after a stroke,14 is not the criterion standard measure to establish the presence of a major depressive episode. Nonetheless, the availability of other pragmatic proxy measures suggests that our approach was most likely associated with few false-negative cases of depression. We acknowledge that by week 26, only 63.3% of participants were alive and had shown good adherence to the study protocol, which may have decreased the power of the study to exclude a modest but potentially important reduction in the risk of depression. Finally, given the long half-life of fluoxetine and its metabolites, its use in a predominantly older population with concurrent morbid conditions should be judicious.8,9,10

Conclusions

The results of the AFFINITY trial showed that the prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression decreases steadily during the first 6 months after a stroke associated with minimal to moderate neurologic deficits, and such a decrease is not affected by the routine daily use of 20 mg of fluoxetine hydrochloride. Current approaches to the prevention and management of clinically significant symptoms of depression after stroke require systematic assessment and attenuation of modifiable risk factors for depression, standardized diagnostic measures, and personalized interventions that are effective and safe rather than the routine prescription of antidepressants for all patients.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants With and Without PHQ-9 at the Start of the Trial

eTable 2. Depression and Treatment Outcomes During the Trial According to Study Country Site

eTable 3. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants With and Without Clinically Significant Symptoms of Depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 9) at the Start of the Trial

eTable 4. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants Without Clinically Significant Symptoms of Depression (PHQ-9 < 9) Who Did and Did Not Develop Depression During the Trial

eTable 5. Intention to Treat Analysis Including All Participants Regardless of Whether or Not They Had Completed a PHQ-9 Assessment at Study Entry

eFigure. Boxplot Showing the Distribution of PHQ-9 Scores According to Treatment Group, Time and Country of Origin

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Hackett ML, Pickles K. Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(8):1017-1025. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allida S, Cox KL, Hsieh CF, House A, Hackett ML. Pharmacological, psychological and non-invasive brain stimulation interventions for preventing depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bech P, Cialdella P, Haugh MC, et al. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine v. placebo and tricyclic antidepressants in the short-term treatment of major depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:421-428. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.5.421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chollet F, Tardy J, Albucher JF, et al. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(2):123-130. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70314-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi ZM, Liu F, Zhai SD. Fluoxetine for the prophylaxis of poststroke depression in patients with stroke: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(9):1310-1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dam M, Tonin P, De Boni A, et al. Effects of fluoxetine and maprotiline on functional recovery in poststroke hemiplegic patients undergoing rehabilitation therapy. Stroke. 1996;27(7):1211-1214. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.27.7.1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson RG, Schultz SK, Castillo C, et al. Nortriptyline versus fluoxetine in the treatment of depression and in short-term recovery after stroke: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(3):351-359. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FOCUS Trial Collaboration . Effects of fluoxetine on functional outcomes after acute stroke (FOCUS): a pragmatic, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10168):265-274. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32823-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EFFECTS Trial Collaboration . Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):661-669. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30219-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AFFINITY Trial Collaboration . Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):651-660. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30207-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mead G, Hackett ML, Lundström E, Murray V, Hankey GJ, Dennis M. The FOCUS, AFFINITY and EFFECTS trials studying the effect(s) of fluoxetine in patients with a recent stroke: a study protocol for three multicentre randomised controlled trials. Trials. 2015;16:369. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0864-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruno A, Akinwuntan AE, Lin C, et al. Simplified modified Rankin Scale questionnaire: reproducibility over the telephone and validation with quality of life. Stroke. 2011;42(8):2276-2279. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner A, Hambridge J, White J, et al. Depression screening in stroke: a comparison of alternative measures with the structured diagnostic interview for the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (major depressive episode) as criterion standard. Stroke. 2012;43(4):1000-1005. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.643296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61-66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyden P, Raman R, Liu L, Emr M, Warren M, Marler J. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale certification is reliable across multiple venues. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2507-2511. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, Burn J, Warlow C. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991;337(8756):1521-1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93206-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steel Z, Silove D, Giao NM, et al. International and indigenous diagnoses of mental disorder among Vietnamese living in Vietnam and Australia. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(4):326-333. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Golledge J, Yeap BB, Flicker L. Depression and the risk of fractures in later life: the Health In Men Cohort Study. Maturitas. 2021;145:6-11. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraglund KL, Mortensen JK, Damsbo AG, et al. Neuroregeneration and vascular protection by citalopram in acute ischemic stroke (TALOS). Stroke. 2018;49(11):2568-2576. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackett ML, Anderson CS, House AO. Management of depression after stroke: a systematic review of pharmacological therapies. Stroke. 2005;36(5):1098-1103. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000162391.27991.9d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razazian N, Esmaeili O, Almasi A. Effect of fluoxetine on motor improvement in ischemic stroke patients: a double blind clincial trial study. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2016;18(7):e7549. doi: 10.17795/zjrms-7549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants With and Without PHQ-9 at the Start of the Trial

eTable 2. Depression and Treatment Outcomes During the Trial According to Study Country Site

eTable 3. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants With and Without Clinically Significant Symptoms of Depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 9) at the Start of the Trial

eTable 4. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants Without Clinically Significant Symptoms of Depression (PHQ-9 < 9) Who Did and Did Not Develop Depression During the Trial

eTable 5. Intention to Treat Analysis Including All Participants Regardless of Whether or Not They Had Completed a PHQ-9 Assessment at Study Entry

eFigure. Boxplot Showing the Distribution of PHQ-9 Scores According to Treatment Group, Time and Country of Origin

Nonauthor Collaborators

Data Sharing Statement