Abstract

This cohort study analyzes inpatient and outpatient episodes of procedural and surgical care to assess the prevalence and costs of low-value preprocedural urinalyses in the US from 2007 to 2017.

Low-value care is a major concern, especially that which leads to additional low-value testing or treatment.1 Urinalyses are an underappreciated area of low-value care, often obtained before procedures despite guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the US Preventive Services Task Force,2,3 as well as evidence that information obtained from urinalyses does not change subsequent management or reduce the risk of infectious complications following procedures. Unlike other low-value services, preprocedural urinalyses may result in use of antibiotics with consequences for both the individual patient and society, including the risk of antimicrobial resistance and adverse effects of antibiotics.4

Methods

We analyzed inpatient and outpatient episodes of procedural and surgical care using 2007 to 2017 IBM Watson MarketScan commercial and Medicare claims,5 with data analysis performed from September 2019 through January 2021. We defined 14 procedure-group families, with each preprocedural episode of care as the 30 days preprocedure. Urinalyses obtained during this time were identified using Current Procedural Terminology codes 81000 through 81020. We defined plausibly indicated urinalyses (clinically higher value) as those obtained in the presence of any of the following diagnoses: acute cystitis, other disorders of the urethra, urethritis, fever, dysuria, altered mental status, urinary frequency, or urinary urgency (eTable in the Supplement). All other urinalyses were deemed nonindicated (clinically lower value). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard Medical School, which waived patient informed consent for use of deidentified data.

In analyses of antibiotic use, individuals with prescription drug coverage were included. Antibiotic prescriptions were associated with a urinalysis if the urinalysis was obtained 1 to 30 days prior to their procedure; urinalyses obtained on the day of the procedure were excluded.

Kidney and urological procedures were excluded owing to the allowance for screening urinalysis in the absence of symptoms based on current guidelines. Cesarean deliveries were also excluded owing to screening recommendations for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy.

Results

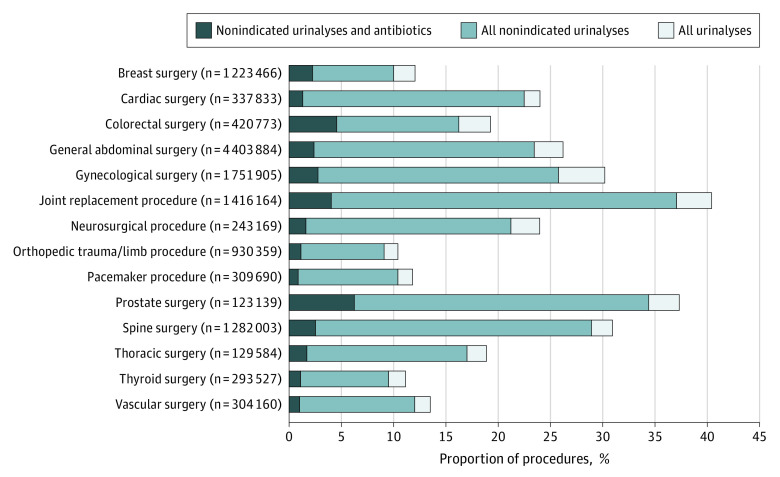

Characteristics of procedure episodes that did and did not receive a urinalysis were similar (Table). Among 13 169 656 procedures, 25% were preceded by urinalyses within 30 days. The proportion of procedures with urinalyses, nonindicated urinalyses, and nonindicated urinalyses with antibiotic prescriptions varied across procedure categories (Figure). Among procedures for which urinalyses were obtained, 89% were not indicated (range, 84%-94% across procedure categories). Among this subset of urinalyses, the mean (SD) price per test was $17 ($108.48), with a mean of 79.5% of the price paid by the insurer. Across procedure categories, between 5.8% and 28.0% of these urinalyses were followed by an antibiotic prescription. Spending on antibiotics ranged from $20 to $65 per course, and the course duration ranged from 5.9 to 10.5 days across procedure groups. Total spending on antibiotic prescriptions declined from $40.61 to $18.19 during the period, mostly owing to decreases in spending on quinolone antibiotics.

Table. Characteristics of Patients With and Without Preoperative Urinalyses (UA).

| Characteristic | Commercial | Medicare | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No UA (n = 7 663 360) | UA (n = 2 849 237) | No UA (n = 2 208 973) | UA (n = 448 086) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 45.2 (14.1) | 45.7 (13.5) | 74.9 (7.6) | 73.5 (6.9) |

| Female, % | 64.8 | 67.1 | 53.5 | 53.3 |

| Male, % | 35.2 | 32.9 | 46.5 | 46.7 |

| Risk scorea | 7.8 | 7.7 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| Plan type, % | ||||

| FFS/other | 4.3 | 3.9 | NA | NA |

| HMO/POS | 20.1 | 18.6 | NA | NA |

| PPO | 66.2 | 68.6 | NA | NA |

| HDHP/CDHP | 9.5 | 8.9 | NA | NA |

| Medicare Advantage | NA | NA | 19.1 | 37.2 |

| Traditional Medicare | NA | NA | 80.9 | 62.8 |

Abbreviations: CDHP, consumer-directed health plan; FFS, fee-for-service; HDHP, high-deductible health plan; HMO, health maintenance organization; NA, not applicable; POS, point-of-service; PPO, preferred provider organization.

The risk score uses concurrent demographic characteristics and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes to calculate a person’s expected health care spending. We used the Diagnostic Cost Group model for the commercial and Medicare populations, which is similar to the Hierarchical Condition Categories model used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for risk adjustment. The risk score models for the commercial population and the Medicare population are different. Thus, those values are not directly comparable.

Figure. Proportion of Procedures With Preoperative Urinalyses, Nonindicated Urinalyses, and Nonindicated Urinalyses Followed by Antibiotic Prescriptions, 2007-2017.

The outcomes, represented by the varied shading, each begin at 0% and are thus overlapping and not stacked.

Discussion

This study found that preprocedural urinalyses were common, but the vast majority were not plausibly indicated; associated antibiotic prescriptions should be considered of no benefit or possibly harmful. The consequences of low-value urinalyses include payer and patient spending on these tests and resulting antibiotics, as well as physician and hospital laboratory costs and transportation costs. Patients and society bear the risk of inappropriate antibiotic use, which can result in adverse drug reactions, increased risk of infections such as Clostridioides difficile, and emergence of antibiotic resistance.

In this population, total spending on inappropriate urinalyses was $48 675 408. We estimated that total spending on antibiotics following inappropriate urinalyses was an additional $4 854 109.

Limitations included potential unobserved factors that could affect the appropriateness of urinalyses or antibiotics, such as clinical information or patient factors that are not reflected in claims data. Moreover, the results may not generalize to other payer populations (eg, Medicaid) or those with different forms of prescription drug coverage that affect antibiotics.

While several successful approaches to reducing both screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria as well as its treatment have been reported—including among preoperative patients—prevailing practice patterns remain entrenched.4,6 Insurers and employers also have a potentially influential role in reducing such low-value care. Through benefit design and payment policies, insurers may target wasteful spending and combat antibiotic resistance.

eTable. Diagnosis Codes Denoting Plausibly Indicated Urinalyses

References

- 1.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(10):1611-1615. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson JT, Webber EM, Bean SI. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1195-1205. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shpunt Y, Estrin I, Levi Y, et al. Antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria—first, do no harm. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(1):37-42. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IBM Watson Health . IBM MarketScan Research Databases for life sciences researchers. Published 2018. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/0NKLE57Y

- 6.Drekonja DM, Zarmbinski B, Johnson JR. Preoperative urine cultures at a Veterans Affairs medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):71-72. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Diagnosis Codes Denoting Plausibly Indicated Urinalyses